Tracing Yoruba Heritage in Brazil Through Olfactory Landscapes: A Sensory Approach to Cultural Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

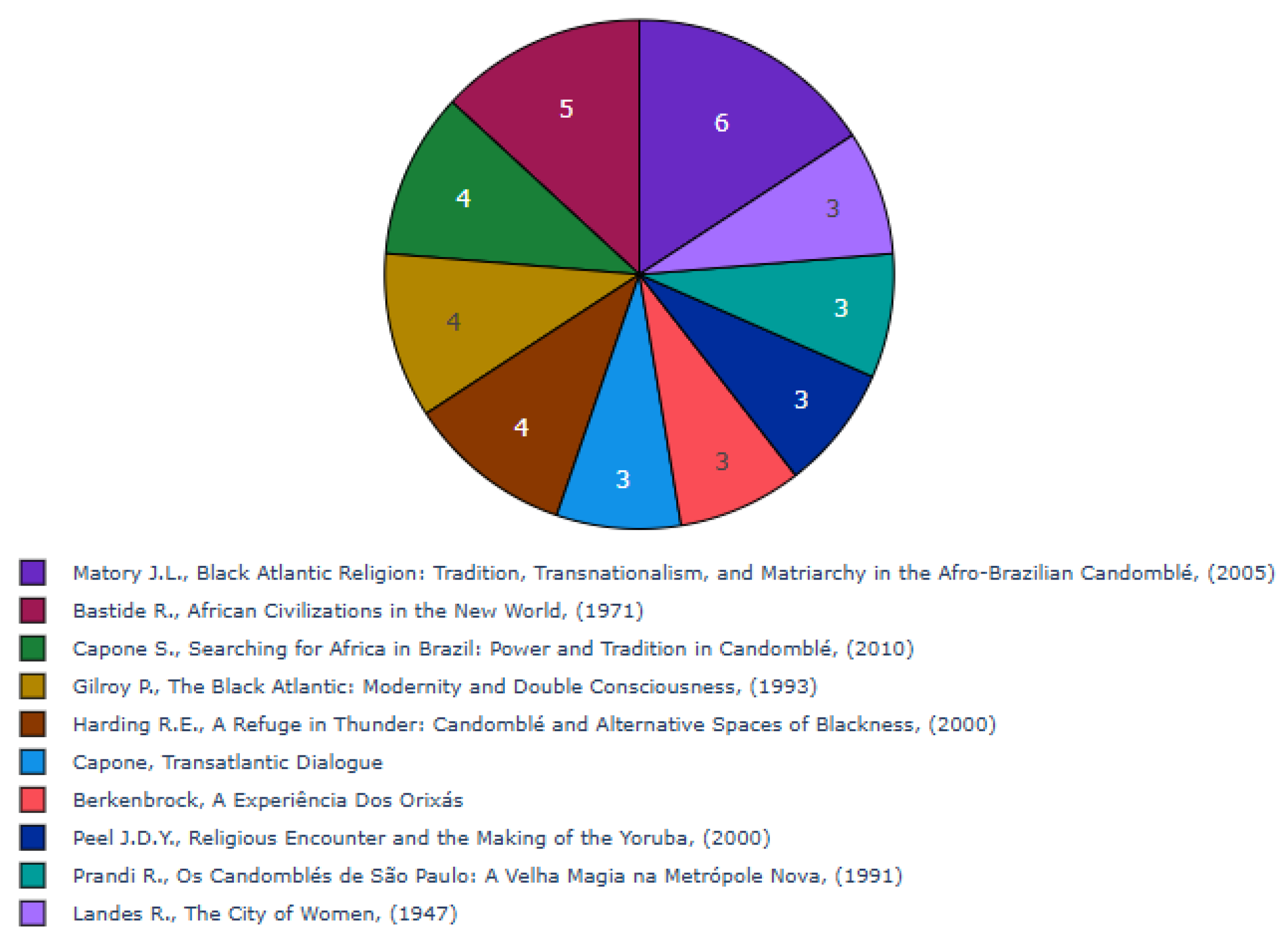

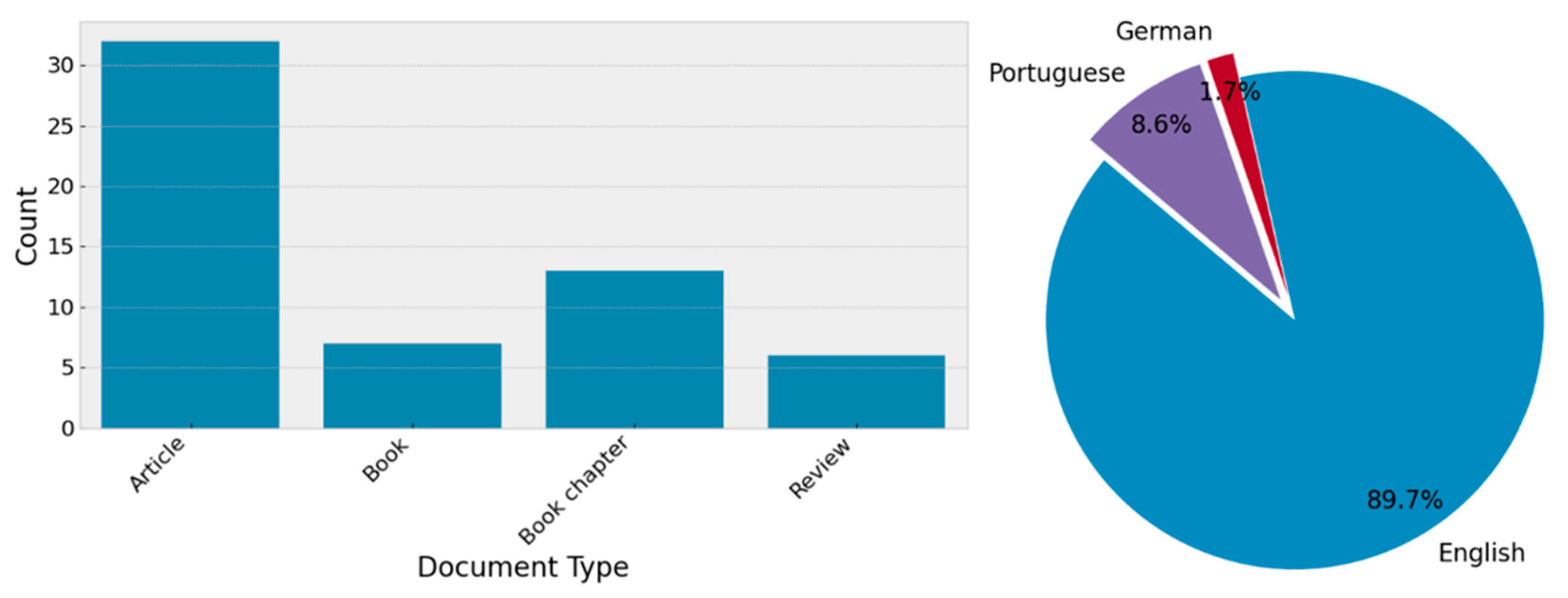

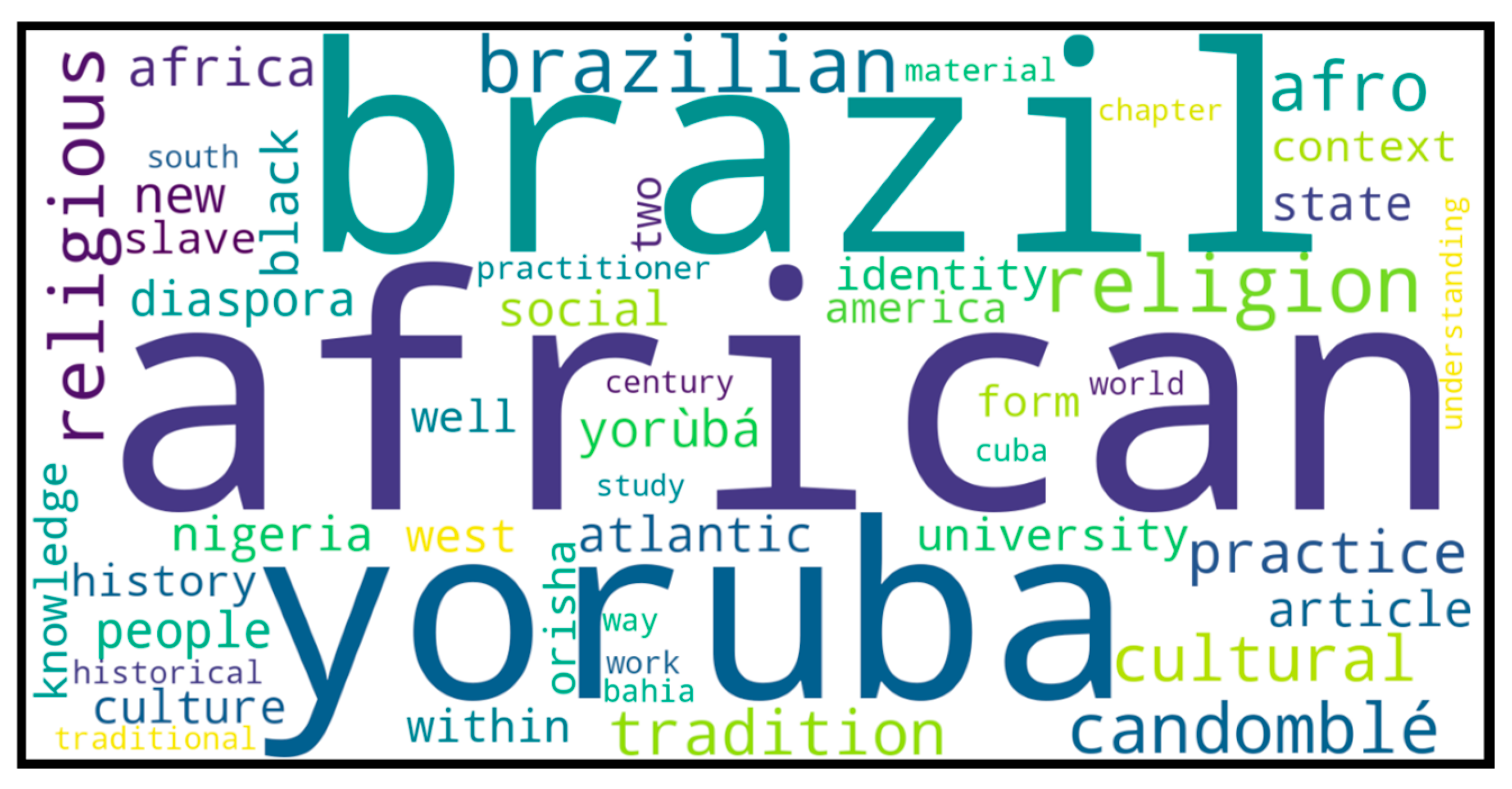

1.1. Systematic Review of the Literature

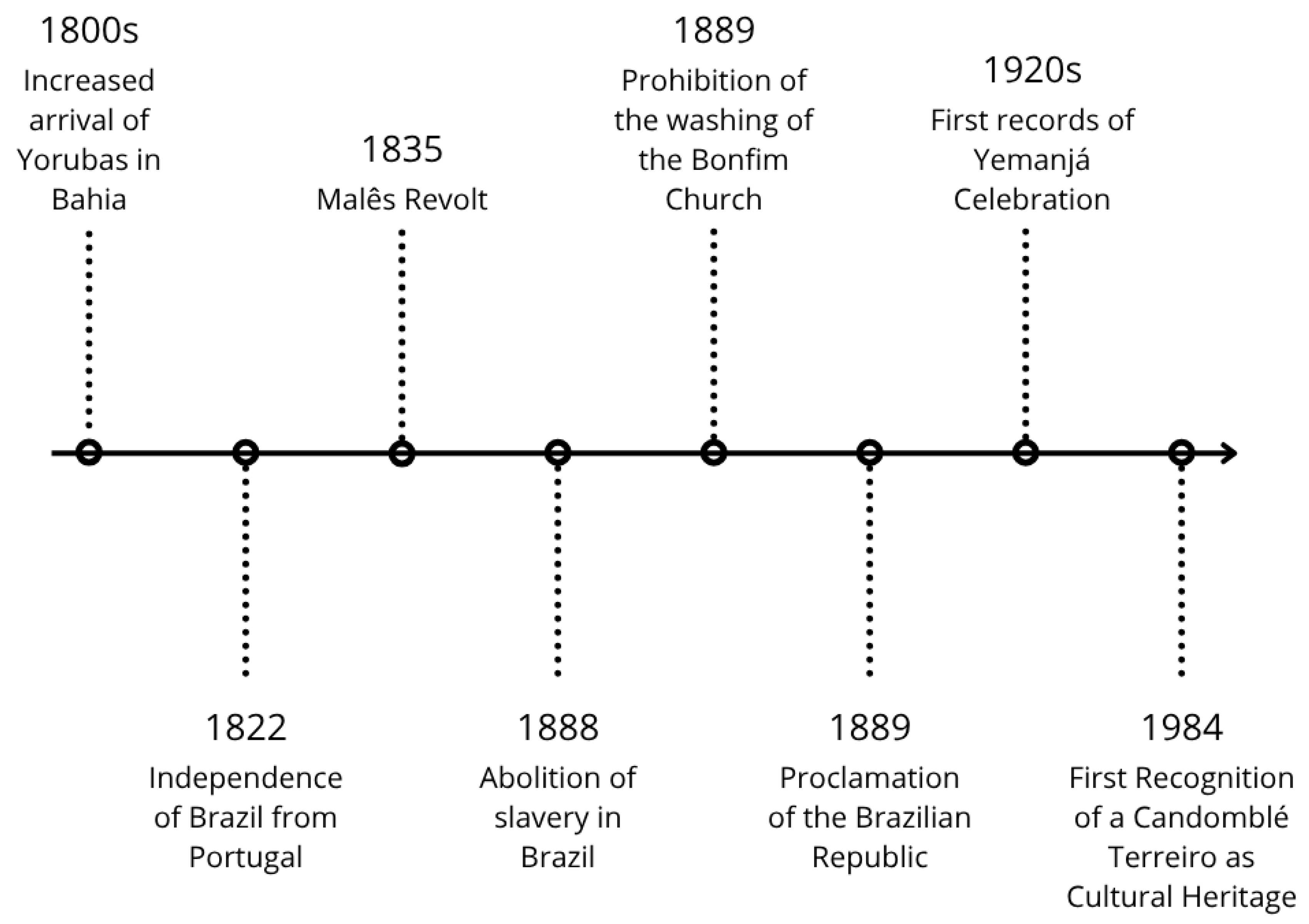

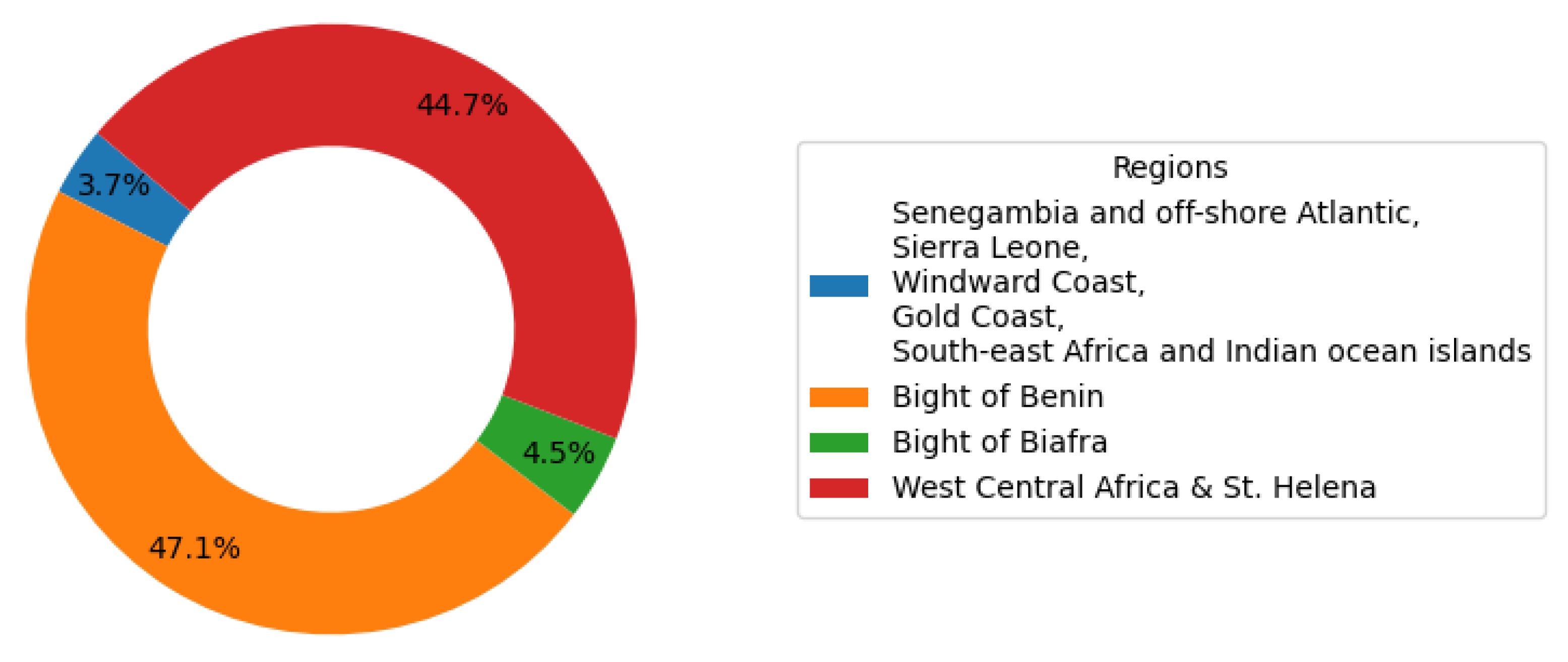

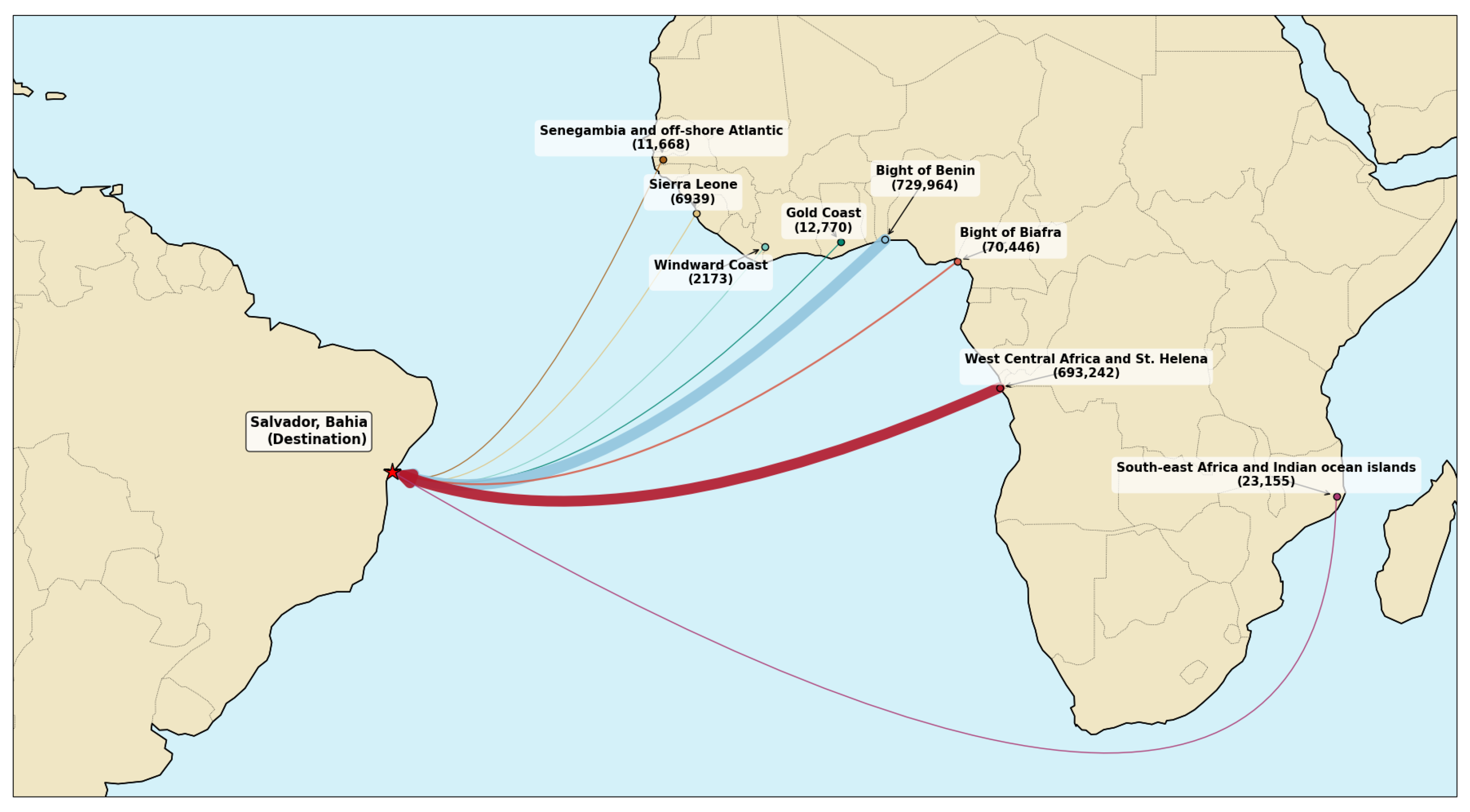

1.2. Historical and Cultural Background

1.3. The Role of Olfaction on Memory and Identity

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fieldwork Observations

2.2. Events Connected with the Lavagem do Bonfim

2.2.1. Mass at Nosso Senhor do Bonfim Church

2.2.2. Nautical Procession

2.2.3. Visit to São Joaquim Fair

2.2.4. Visit to Memorial das Baianas

2.2.5. Lavagem do Bonfim

2.3. Festa de Iemanjá

2.4. Oduduwa Temple of Orixás

3. Results

Similarities Between the Scents of Yoruba Practices and Bahia’s Cultural Manifestations

- Woody: The grounding scent of incense used in Salvador’s Senhor do Bonfim Church finds a parallel in the aroma emanating from the offering made in honor of the deity Orunmilá, and Yoruba temple. More widely, the whole estrela, place dedicated to the honoring of the deities, had a woody scent, suggesting a shared preference for woody fragrances in a sacred context.

- Spicy: This note was present in the Senhor do Bonfim church incense, in the feijoada of the Nautical Procession in Bahia, and on the streets of Salvador due to the preparation of acarajé. At the temple, a similar spicy character, reminiscent of stewing herbs, defined the ceremonial cleansing bath preparation.

- Indole: Often associated with specific white flowers or with decaying organic matter, this heavy, sometimes challenging note was sensed in the elaborate flower decorations within Bahian churches and, more intensely, on the ritual table representing the negativity of the lives of the people undergoing initiations at the temple. Here, it is interesting to note the stark difference in context, one positive, one negative. And yet, the fragrance note still connects both cultures, being used for a sacred purpose in both instances.

- Rosemary: The distinct herbal fragrance of rosemary was noted in the myrrh used for the perfumed water (água de cheiro) during the Lavagem do Bonfim and echoed in the profile of the Yoruba cleansing bath. Here, the context of cleansing is the same.

- Salty: The salty aroma of the ingredients of the feijoada used at the Nautical Procession in Bahia, complemented by the oceanic environment of the event, is mirrored in the stew-like scent of the temple’s cleansing bath.

- Meaty: Once more, the similarity between the aromas of the food at the Nautical Procession is strongly mirrored in the temple’s cleansing bath preparation, despite its difference in terms of ingredients. The aroma of the feijoada is congruent with its purpose, to be eaten, while the cleansing bath has a surprising aroma of food while serving as a cleansing medium. Nevertheless, the similarity is still present.

- Palm Oil: As mentioned, this is a unifying aromatic signature, prominent in Bahian acarajé and detected on the ritual table, at the Orunmilá offering site, within the sacrificial blood collection area, and generally around places where offerings are left at the temple.

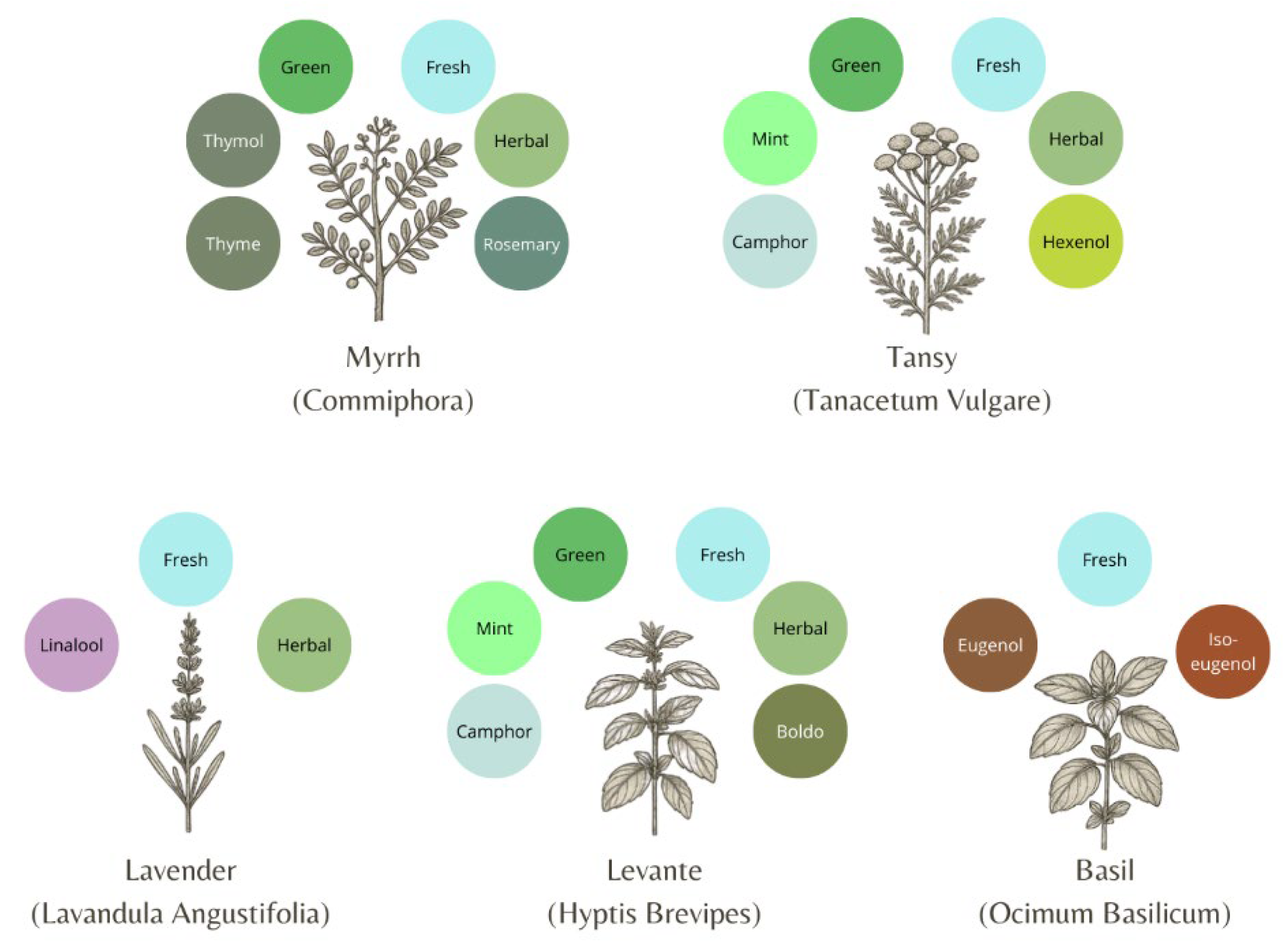

- Myrrh (Commiphora africana): Verger’s work mentions the plant in three different contexts, all applied to beneficent works, such as to find a job, wake up well and achieve good fortune [78]. In El Monte, the plant is not included in the encyclopedia section, but myrrh is mentioned elsewhere, usually in the context of being burned to use as incense [79], highlighting its aromatic property, one of the main reasons why it is used in the água de cheiro. It is also used in medicinal contexts and is associated with the deity Oshun [60,80].

- Basil (Ocimum basilicum): It is well-documented in Yoruba practices, with works focusing exclusively on the ethnobotany of the plant, and its uses as a medicine [81]. In Verger’s work, the listed uses are for healing various ailments (child sickness, smallpox, giddiness) [78]. In El Monte, its listed uses are to cleanse the body and as medicine. Additionally, it is said that its aroma can be embedded in handkerchiefs and used to counteract “the evil eye” [79]. This aromatic focus once more reinforces the link between the use of the herb for its aromatic properties in Bahia and in other Yoruba-influenced cultures.

- Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus): This plant is not mentioned in Verger’s work but is recognized on the Yoruba-derived religions of Santería and Candomblé. In El Monte, it is said to aid in childbirth, rheumatism, headaches and bronchitis. It is also mentioned that the plant’s “aroma is a secret that should be kept quiet”. This indicates the recognition of the aroma of the plant as an important tool, even if it is not discussed in detail [79]. It is speculated that the plant was introduced into Afro-Brazilian practices like Candomblé through Bantu influences [82], an ethnolinguistic group from sub-Saharan Africa. This indicates that the use of the plant is an adaptation that occurred in the Americas and might not trace its roots to the Yoruba culture.

- Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia): It is not mentioned by Verger’s work or in El Monte. Nevertheless, its use is common in Afro Brazilian culture such as candomblé [83], and is observed in many cultural manifestations such as the Lavagem do Bonfim and the Festa de Iemanjá [9,67]. The use of lavender as a perfume and fragrance note is very well diffused in Bahia, and as such, the use of Lavender for religious and cultural purposes might indicate an adaptation made by the Brazilian of the Yoruba culture, considering their own preferences and availability [84].

- Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), Levante (Hyptis brevipes), and Dill (Anethum graveolens): The literature consulted did not indicate specific traditional uses within the core Yoruba practices referenced. This could also indicate that the use of these plants was an adaptation of Yoruba culture by Afro-Brazilians.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Complementary Information on the Bibliometric Analysis

| Country | Number of Works |

|---|---|

| United States | 25 |

| Brazil | 16 |

| Nigeria | 4 |

| Canada | 3 |

| France | 2 |

| Australia | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 1 |

| Country not disclosed | 10 |

| Institution | Number of Works |

|---|---|

| University of Texas | 4 |

| Obafemi Awolowo University | 3 |

| Columbia University | 2 |

| Universidade de São Paulo | 2 |

| Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina | 2 |

| Northwestern University | 2 |

| Universidade Federal da Bahia | 2 |

| Other Institutions | 37 |

| Institution not disclosed | 13 |

| Title | Authors | Year | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| The English professors of Brazil: On the diasporic roots of the Yorùbá nation | Matory, J. Lorand | 1999 [88] | 147 |

| City of 201 gods: Ilé-Ifè in time, space, and the imagination | Olúpònà, Jacob K. | 2011 [89] | 81 |

| The formation of Candomble: Vodun history and ritual in Brazil | Parés, Luis Nicolau | 2013 [90] | 47 |

| Nagô and Mina: The Yoruba diaspora in Brazil | Reis, João José and Mamigonian, Beatriz Gallotti | 2004 [91] | 34 |

| Santería: Correcting the Myths and Uncovering the Realities of a Growing Religion | Clark, Mary Ann | 2007 [92] | 34 |

| Yorúbá influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo | Fandrich, Ina J. | 2007 [93] | 30 |

| Nagô Grandma and White Papa: Candomblé and the creation of Afro-Brazilian identity | Dantas, Beatriz Góis and Berg, Stephen | 2009 [94] | 27 |

| Mollusks of Candomblé: Symbolic and ritualistic importance | Léo Neto, Nivaldo A. and Voeks, Robert A. and Dias, Thelma L.P. and Alves, Rômulo R.N. | 2012 [95] | 24 |

| Gendered agendas: The secrets scholars keep about Yorùbá-Atlantic religion | Matory, J. Lorand | 2004 [96] | 24 |

Appendix B. Details on the Progressive Emancipation of the Enslaved Population of Brazil

References

- Udo, E.M. The Vitality of Yoruba Culture in the Americas. Ufahamu 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falola, T.; Childs, M.D. The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- SlaveVoyages, Estimates. Available online: https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Akintoye, S.A. A History of the Yoruba People; Amalion: Dakar, Senegal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico 2022: Identificação Étnico-Racial da População, por Sexo e Idade: Resultados do Universo; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.M. Yoruba Religions in Diaspora. Relig. Compass 2010, 4, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofuasia, E. Some comments over the Yorùbá origins of Candomblé and other Afro-Brazilian Religions. Yoruba Stud. Rev. 2024, 9, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.C. Food and spirits: Religion, gender, and identity in the ‘African’ cuisine of Northeast Brazil. Afr. Black Diaspora Int. J. 2012, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz, M.M.A. Folias Divinas em Redes: Patrimônio Imaterial, Gestão Cultural e Economia Criativa na Festa de Iemanjá em Salvador; UFBA: Salvador, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, L.L. Os Colares Sagrados da Memória: Tradição, Axé e Identidade no Candomblé de Matriz Africana Iorubá; UESB: Vitória da Conquista, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Dossiê de Registro–Festa do Senhor Bom Jesus do Bonfim; IPHAN: Brasília, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halloy, A. L’odeur de l’axé. J. Soc. Am. 2018, 104, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.A. Scenting Salvation; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, A. Human Olfaction at the Intersection of Language, Culture, and Biology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoch, J.; McDonald, L.; Jones, L.; Jones, P.R.; Crabb, D.P. Evaluating Whether Sight Is the Most Valued Sense. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 1317–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlinzig, T. Odor as a medium of cohesion and belonging1. Rech. Sociol. Anthr. 2021, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembibre, C.; Strlič, M. Smell of heritage: A framework for the identification, analysis and archival of historic odours. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembibre, C.; Strlič, M. From Smelly Buildings to the Scented Past: An Overview of Olfactory Heritage. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeuropa. The Odeuropa Smell Explorer. Available online: https://explorer.odeuropa.eu/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Lisena, P.; Ehrhart, T.; Troncy, R.; Leemans, I.; Marieke, V.E. European Olfactory Knowledge Graph; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hub, H.R. ODOTHEKA. 2025. Available online: https://www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/project/odotheka/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Climate, J. SCENTINEL. 2025. Available online: https://jpi-climate.eu/project/scentinel/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Osmothèque. About|Osmothèque. Available online: https://www.osmotheque.fr/en/about/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- UNESCO. The Skills Related to Perfume in Pays de Grasse: The Cultivation of Perfume Plants, the Knowledge and Processing of Natural Raw Materials, and the Art of Perfume Composition. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/the-skills-related-to-perfume-in-pays-de-grasse-the-cultivation-of-perfume-plants-the-knowledge-and-processing-of-natural-raw-materials-and-the-art-of-perfume-composition-01207 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- UNESCO. Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlase, I.; Lähdesmäki, T. A bibliometric analysis of cultural heritage research in the humanities: The Web of Science as a tool of knowledge management. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier B.V. Scopus. 2025. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Pereira, V.; Basilio, M.P.; Santos, C.H.T. PyBibX–a Python library for bibliometric and scientometric analysis powered with artificial intelligence tools. Data Technol. Appl. 2025, 59, 302–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, A.; Maisonobe, M.; Boukacem-Zeghmouri, C. Geographical and disciplinary coverage of open access journals: OpenAlex, Scopus, and WoS. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustamaji, H.C.; Kusuma, W.A.; Nurdiati, S.; Batubara, I. Community detection with Greedy Modularity disassembly strategy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.F. PolÍticas De Identidade No Contexto Da DiscussÃo Racial: A Academia Negra No Brasil. Psicol. Soc. 2017, 29, e171201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintans-Junior, L.J.; Guedes Gomes, F. The abyss of research funding in Brazil. EXCLI J. 2024, 23, 1491–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, P.d.A. Salvador: Transformações e Permanências (1549–1999); EDUFBA: Salvador, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Recenseamento do Brazil em 1872; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Uya, O. The African Diaspora and the Black Experience in New World Slavery; Okpaku Communications Corp.: New Rochelle, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kananoja, K. Central African Identities and Religiosity in Colonial Minas Gerais; Uniprint: Turku, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Y.P. Location and Origin of Black People Enslaved in the Brazilian Colonial Territory: The Bantu and Yoruba Designations. Eletronic Mag. Time-Tech.-Territ. 2012, 3, 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.S. Everyday and Esoteric Reality in the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé. Hist. Relig. 1990, 30, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Cano, J. Entre Oyá y Santa Teresa. El controvertido asunto del sincretismo en la santería. Gaz. Antropol. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.o.J. Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia; Johns Hopkins Studies in Atlantic History and Culture; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira, M.D.; de Godoi, M.M. Escravidão, Resistência e Abolição. Semina 2018, 17, 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca Nacional (Brasil). Para uma Historia do Negro No Brasil; Biblioteca Nacional (Brasil): Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, W.d. Legado da lei Áurea: O Racismo Institucional e a Negação do Negro Enquanto Sujeito Histórico. Rev. Estud. Anarquistas Decoloniais 2023, 3, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Dossiê de Registro–Oficio das Baianas de Acaraje; IPHAN: Brasília, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Capone, S. A Busca da África No Candomblé; Pallas: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino, A.C.S. (Não) Deu Na Primeira Página: Macumba, Loucura E Criminalidade; Universidade Federal de Sergipe: São Cristóvão, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, D.d.S. Festa e fé Análise do Planejamento e Organização da Festa de Iemanjá da Cidade de Salvador; Departamento de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia da Bahia: Salvador, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, E.S. Festa de Santa Bárbara e Iansã: Os baianos entre fronteiras tênues e complementação de crenças. Rev. Bras. Hist. Relig. 2018, 11, 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, R.D.S. A Festa do Milagre de São Roque no Município de Amélia Rodrigues–Ba: Relações Étnico-Raciais e a Cultura Popular em Questão; Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana: Feira de Santana, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Terreiro Casa Branca do Engenho Velho-Salvador (BA). Available online: http://portal.iphan.gov.br/pagina/detalhes/1636/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Capone, S. Re-Africanization in Afro-Brazilian Religions: Rethinking Religious Syncretism, in Handbook of Contemporary Religions in Brazil; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 473–488. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R.S.; Schooler, J.W. A Naturalistic Study of Autobiographical Memories Evoked by Olfactory and Visual Cues: Testing the Proustian Hypothesis. Am. J. Psychol. 2002, 115, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafoleanu, C.; Mella, C.; Georgescu, M.; Perederco, C. The importance of the olfactory sense in the human behavior and evolution. J. Med. Life 2009, 2, 196. [Google Scholar]

- Classen, C.; Howes, D.; Synnott, A. Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, G.M. Perception without a thalamus how does olfaction do it? Neuron 2005, 46, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beukelaer, S.; Sokolov, A.A.; Muri, R.M. Case report: “Proust phenomenon” after right posterior cerebral artery occlusion. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1183265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.A. Learning to Smell: Olfactory Perception from Neurobiology to Behavior; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karade, B.I. The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts; Samuel Weiser Inc.: York Beach, ME, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Voeks, R. Sacred Leaves of Candomblé; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer Willis, L. “It smells like a thousand angels marching”: The Salvific Sensorium in Rio de Janeiro’s Western Subúrbios. Cult. Anthropol. 2018, 33, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettler, A. The Smell of Slavery; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, A. Anthropology and Odor: From Manhattan to Mato Grosso. Perfum. Flavourist 1988, 13, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. Los Marcos Sociales de la Memoria; Universidad Central de Venezuela: Caracas, Venezuela, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tullett, W. Smell and the Past: Noses, Archives, Narratives; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, R.C.G. Da Conceição da Praia à Colina Sagrada. Rev. USP 2016, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S. Influences of Odors on Mood and Affective Cognition. In Olfaction, Taste, and Cognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 160–177. [Google Scholar]

- Elkholi, S.M.A.; Abdelwahab, M.K.; Abdelhafeez, M. Impact of the smell loss on the quality of life and adopted coping strategies in COVID-19 patients. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 3307–3314. [Google Scholar]

- Company, T.G.S. Odor Type Listing. 2025. Available online: https://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/allodor.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Aquino, A. Mais de 1 Milhão Participam de Lavagem do Bonfim, em Salvador, in Estadão. 2008. Available online: https://www.estadao.com.br/brasil/mais-de-1-milhao-participam-de-lavagem-do-bonfim-em-salvador/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Borges, T. Que Bonfim é esse? Festa reúne 2 milhões de pessoas e bate recorde. Correio 24 Horas, 17 January 2019.

- Carneiro, L. Lavagem do Bonfim reúne 2 milhões de pessoas em celebração que mostra a resistência negra no país. Brasil de Fato, 16 January 2025.

- Viegas, J. Feira de São Joaquim: Potencialidades e limites na visão do setor público. Semin. Estud. Prod. Acad. 2006, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Bens Imateriais em Processo de Instrução para Registro. Available online: http://portal.iphan.gov.br/pagina/detalhes/426 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Ogunnaike, A. What’s Really Behind the Mask: A Reexamination of Syncretism in Brazilian Candomblé. J. Afr. Relig. 2020, 8, 146–171. [Google Scholar]

- Oduduwa. Centro Cultural. 2017. Available online: https://oduduwa.com.br/?cont=centro-cultural (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Verger, P.F. Ewé: The Use of Plants in Yoruba Society; Schwarcz LTDA: São Paulo, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, L.; Font-Navarrete, D. El Monte: Notes on the Religions, Magic, and Folklore of the Black and Creole People of Cuba; Latin America in translation/en traducción/em tradução; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Odugbemi, T. A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from Nigeria; Univeristy of Lagos Press: Lagos, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Andrade, L.H.C. Etnobotanica del género Ocimum L. (Lamiaceae) en las comunidades afrobrasileñas. An. Jard. Bot. Madr. 1998, 56, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, F.N.; Balick, M.J. Plant-Knowledge Adaptation in an Urban Setting: Candomblé Ethnobotany in New York City. Econ. Bot. 2018, 72, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sátiro, L.N.; Vieira, J.H.; Rocha, D.F.d. Uso MÍstico, MÁgico E Medicinal De Plantas Nos Rituais Religiosos De CandomblÉ No Agreste Alagoano. Rev. Ouricuri 2019, 9, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nery, S. O gosto e o cheiro: Práticas de consumo e diferenças regionais no Brasil. Estud. Sociol. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceicao, D.T. Ogbà Mimó-Livro das Folhas Sagradas; D7 Editora: Campinas, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Guidelines for the Application of IUCN Red List of Ecosystems Version 2.0; Keith, D.A., Ferrer-Paris, J.R., Ghoraba, S.M.M., Henriksen, S., Monyeki, M., Murray, N.J., Nicholson, E., Rowland, J., Skowno, A., Slingsby, J.A., et al., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, S.P.; Brown, M.J.M.; Leão, T.C.C.; Nic Lughadha, E.; Walker, B.E. Extinction risk predictions for the world’s flowering plants to support their conservation. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 797–808. [Google Scholar]

- Matory, J.L. The English Professors of Brazil: On the Diasporic Roots of the Yorùbá Nation. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1999, 41, 72–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olupona, J.K. City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parés, L.N. The Formation of Candomblé: Vodun History and Ritual in Brazil; Latin America in translation/en traducción/em tradução; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, J.J.; Mamigonian, B.G. Nagô and Mina: The Yoruba diaspora in Brazil. In The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2004; pp. 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M.A. Santería: Correcting the Myths and Uncovering the Realities of a Growing Religion; Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fandrich, I.J. Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo. J. Black Stud. 2007, 37, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, B.G.B. Nagô Grandma and White Papa: Candomblé and the Creation of Afro-Brazilian Identity; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Léo Neto, N.A.; Voeks, R.A.; Dias, T.L.; Alves, R.R. Mollusks of Candomblé: Symbolic and ritualistic importance. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matory, J.L. Gendered Agendas: The Secrets Scholars Keep about Yorùbá--Atlantic Religion. Gend. Hist. 2004, 15, 409–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matory, J.L. Black Atlantic Religion: Tradition, Transnationalism, and Matriarchy in the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bastide, R. African Civilisations in the New World; Billing & Sons Limited: Guildford, UK; London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Capone Laffitte, S.; Grant, L.L. Searching for Africa in Brazil; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, P. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, R.E. A Refuge in Thunder: Candomble and Alternative Spaces of Blackness; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Capone, S. Transatlantic Dialogue: Roger Bastide and the African American Religions. J. Relig. Afr. 2007, 37, 336–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkenbrock, V.J. A Experiência dos Orixás: Um Estudo Sobre a Experiência Religiosa no Candomblé; Editora Vozes: Manaus, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, J.D.Y. Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba; Indiana Universty Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Prandi, J.R. Os Candombles De Sao Paulo: A Velha Magia Na Metropole Nova; HUCITEC: São Paulo, Brazil, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Landes, R. The City of Women, 2nd ed.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto, B. História do Brasil, 12th ed.; Editora da Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, A. História do Brasil; Cia. Editora Nacional: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Priore, M.; Venancio, R. Uma Breve História do Brasil; Editora Planeta: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Search Query | Goal of the Query | Number of Works Found |

|---|---|---|

| ALL(Yoruba AND Brazil) | Broadest query to retrieve the maximum number of records related to both terms, regardless of where these terms appear. | 2308 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY(Yoruba AND Brazil) | Targeted search limited to titles, abstracts, and keywords to capture works directly related to the research theme. | 66 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY(Yoruba AND Bahia) | Focused query emphasizing a more specific geographic scope, aligned with the study’s emphasis on Bahia. | 19 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY(Yoruba AND Brazil) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(aroma OR smell OR scent OR olfactory OR odor OR olfaction) | Specific query combining thematic focus with olfactory terms to identify directly relevant sensory literature. | 0 |

| ALL(Yoruba AND Brazil) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(aroma OR smell OR scent OR olfactory OR odor OR olfaction) | Broader version of the previous query to capture any mention of olfactory aspects in works otherwise related to Yoruba and Brazil. | 6 |

| Main Event | Event | Date | Geographic Coordinates | Cultural Roots | Main Olfactory Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lavagem do Bonfim | Mass at Nosso Senhor do Bonfim Church | 14th of January | 12°55′25.0″ S 38°30′29.2″ W | Catholic ceremony | Incenses, flowers |

| Visit to São Joaquim Fair | 14th of January | 12°57′07.2″ S 38°30′07.2″ W | Afro-Brazilian, with influences from all cultures present in the city of Salvador | Various scents from herbs, spices, plants, flowers, culinary ingredients, and others | |

| Nautical Procession | 15th of January | 12°59′58.1″ S 38°32′02.1″ W | Catholic ceremony | Marine environment and traditional foods | |

| Visit to the National Association of Baianas de Acarajé | 15th of January | 12°58′24.5″ S 38°30′43.1″ W | Afro-Brazilian | Scent from the plants and flowers used to create the “água de cheiro”, as well as the smell of the freshly cleaned white clothes | |

| Lavagem do Bonfim | 16th of January | 12°55′26.2″ S 38°30′29.7″ W | Syncretic ceremony with catholic and Afro-Brazilian influences, but presence of people from diverse backgrounds | “Água de cheiro”, herbs, as well as traditional foods sold by the baianas | |

| Oduduwa Temple of Orixás | Visit to Oduduwa Temple of Orixás | 25th–31st of January | 24°07′27.3″ S 46°40′37.4″ W | Yoruba | Various aromatic ingredients used for offerings, ceremonial purposes, and for food |

| Festa de Iemanjá | Festa de Iemanjá | 2nd of February | 13°00′45.5″ S 38°29′31.5″ W | Afro-Brazilian, with presence of people from diverse backgrounds | Flowers used as offerings, as well as lavender perfume |

| Fragrance Note | Lavagem do Bonfim | Oduduwa Temple of Orixás | Festa de Iemanjá |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woody | X | X | |

| Spicy | X | X | |

| Indole | X | X | |

| Rosemary | X | X | |

| Salty | X | X | |

| Meaty | X | X | |

| Palm oil | X | X | |

| Floral | X | X | |

| Lavender | X | X | |

| Sweaty | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, B.C.L.; Queiroz, L.P.; Fleming, B.; Vieira, N.J.; Ribeiro, R.I.; Caldas, A.S.; Leblebici, M.E.; Strlic, M.; Nogueira, I.B.R. Tracing Yoruba Heritage in Brazil Through Olfactory Landscapes: A Sensory Approach to Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2025, 8, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110457

Rodrigues BCL, Queiroz LP, Fleming B, Vieira NJ, Ribeiro RI, Caldas AS, Leblebici ME, Strlic M, Nogueira IBR. Tracing Yoruba Heritage in Brazil Through Olfactory Landscapes: A Sensory Approach to Cultural Heritage. Heritage. 2025; 8(11):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110457

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Bruno C. L., Luana P. Queiroz, Bernardo Fleming, Noemi J. Vieira, Ronilda Iyakemi Ribeiro, Alcides S. Caldas, Mumin Enis Leblebici, Matija Strlic, and Idelfonso B. R. Nogueira. 2025. "Tracing Yoruba Heritage in Brazil Through Olfactory Landscapes: A Sensory Approach to Cultural Heritage" Heritage 8, no. 11: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110457

APA StyleRodrigues, B. C. L., Queiroz, L. P., Fleming, B., Vieira, N. J., Ribeiro, R. I., Caldas, A. S., Leblebici, M. E., Strlic, M., & Nogueira, I. B. R. (2025). Tracing Yoruba Heritage in Brazil Through Olfactory Landscapes: A Sensory Approach to Cultural Heritage. Heritage, 8(11), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110457