Climate Change and Historical Food-Related Architecture Abandonment: Evidence from Italian Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Materials and Methods. Sources are listed and methodology is illustrated. Methodology consists of two subsections:

- The theoretical concept of climatic indicators, as an answer to some environmental history questions, is introduced, and the tools elaborated for the analysis of case studies are illustrated.

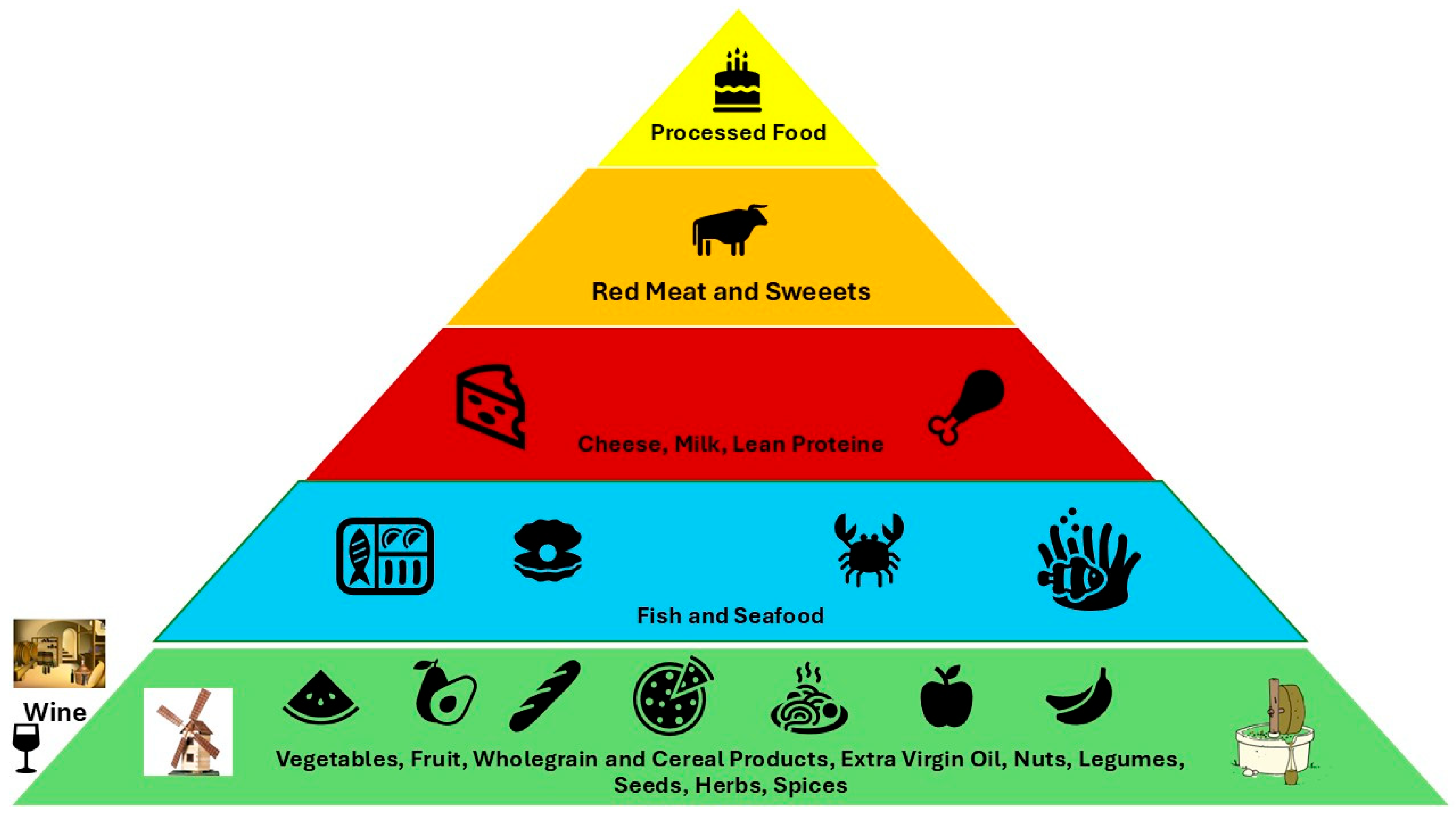

- The Italian pyramid of the UNESCO Mediterranean diet is introduced, and the connection between food-related architecture and corresponding food specialties is established.

- Results and Discussion, where case studies, selected based on their significance within Italian foods listed in the UNESCO Mediterranean Diet, are studied. The selection was carried out by highlighting some architectures that supported the production of the most iconic Italian food specialties: olive oil, wine and wholegrains. Each case study was analyzed in a separate subsection. In each of them, climatic factors connected to the building and abandonment of the corresponding case study are analyzed, also adopting the introduced tools. In the final part of each subsection, the state of the corresponding enhancement processes is studied, and some focus points for their interpretation, based on their potential as climatic indicators, are listed. Then, results from previous analysis are discussed and summarized. Results are reported in a table which together with two charts, is part of the toolkit provided to support future analysis regarding the relationship between food-related architecture and climate change at a global level.

- Conclusions, where a summary of the research results is given.

2. Materials and Methods

- Bibliographic data and research results from the literature regarding the historical reconstruction of climatic changes, history of technologies and local productions, reports regarding the history of selected case studies, descriptions of UNESCO properties from the UNESCO lists and UNESCO tentative list dossiers;

- Data regarding the enhancement of rural cultural heritage from academic studies and institutional databases and websites;

- Results from onsite inspections.

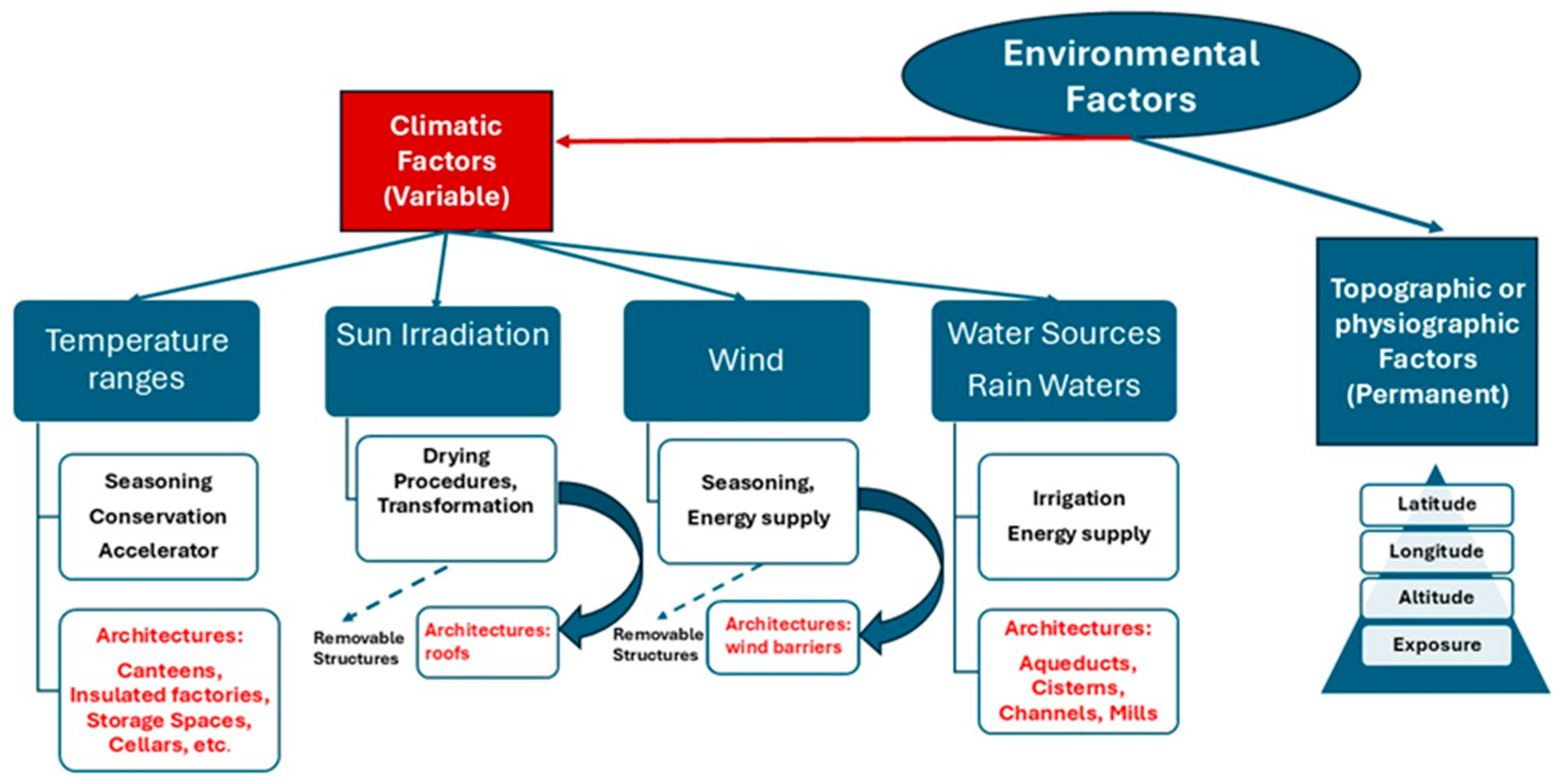

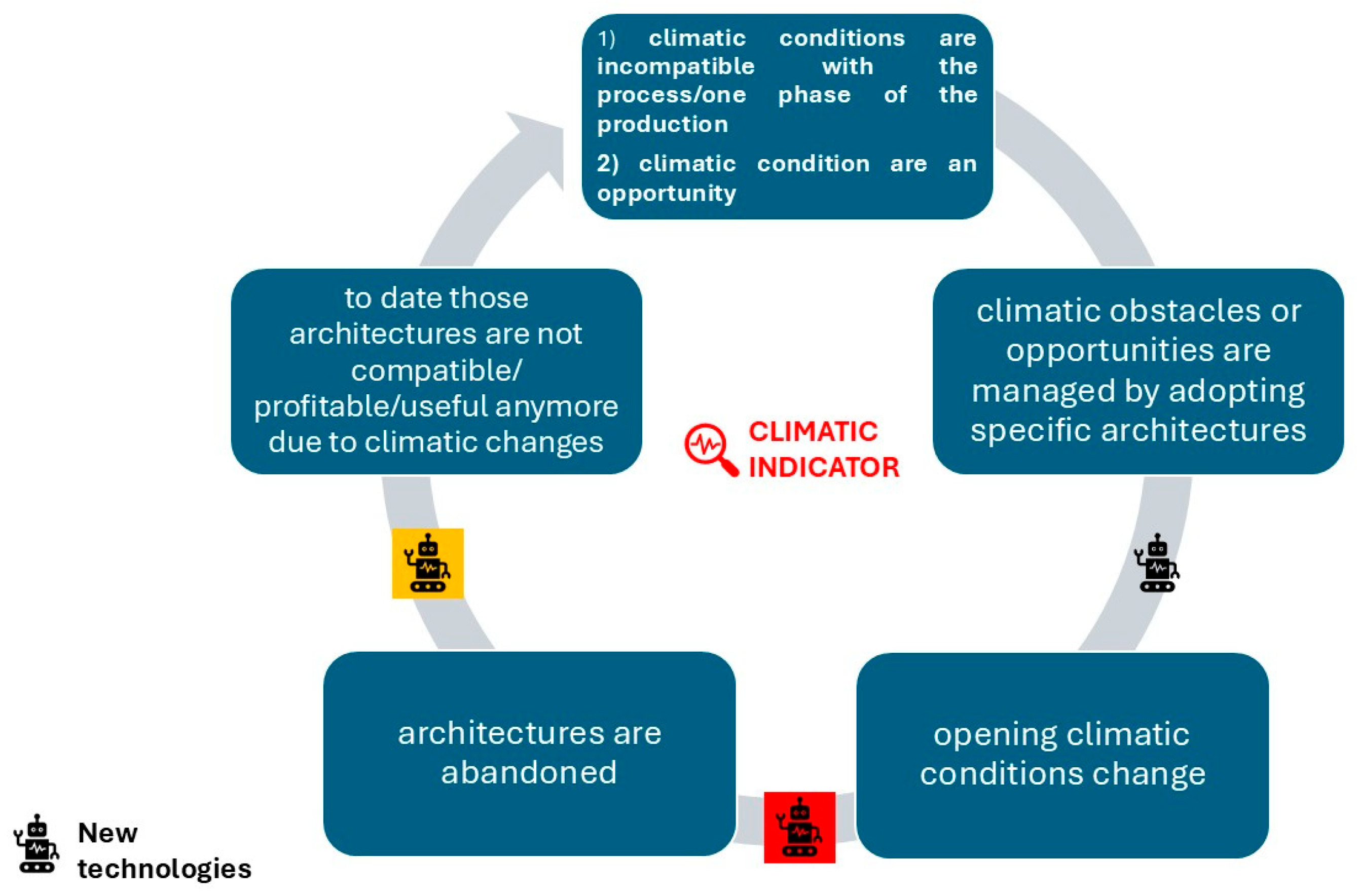

- Food-related architecture and climatic factors are introduced as a resource for environmental history. This approach focuses on the lack of historical data series regarding historical long-term climatic changes and on the potential of some food-related architectures in covering this gap. This issue was addressed by introducing the theoretical concept of climatic indicators, and two charts were elaborated to test the potential of selected food-related architectures from this perspective. The first chart illustrates all the possible interconnections between food-related architecture and permanent and variable climatic factors. The second allows for the description of variations in the relationship between those artefacts and climatic changes, also introducing the variable of technological advancement. Finally, some examples from the international scenario are provided.

- The second phase focuses on food-related architecture connected to the Mediterranean diet—inscribed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Values List—and on the so-called pyramid of the Italian diet: a graphical representation of the ideal combination of Italian food specialties listed in the diet. In this phase, different sources—bibliography, website data, institutional documents, etc.—were adopted. Then, a new graphical representation of the pyramid was introduced: symbols of food-related architecture have been added in correspondence to those specialties located at the base of the pyramid and suggested for daily use. Their role as elements of the rural cultural landscape in Italy is also introduced, with a special focus on the relationship between the theoretical concept of nature and climatic changes.

2.1. Food-Related Architecture and Climatic Factors

- The first group includes fixed climatic factors: latitude, longitude, altitude and exposure.

- The second group includes variable climatic factors: temperature, solar radiation, wind and water resources from renewable and meteoric sources.

- Temperature: cellars, heat-insulated factories, warehouses, etc. [9].

- Solar irradiation: processing of products and their drying, either using removable structures—typically made of wood—or using the roofs of built architecture.

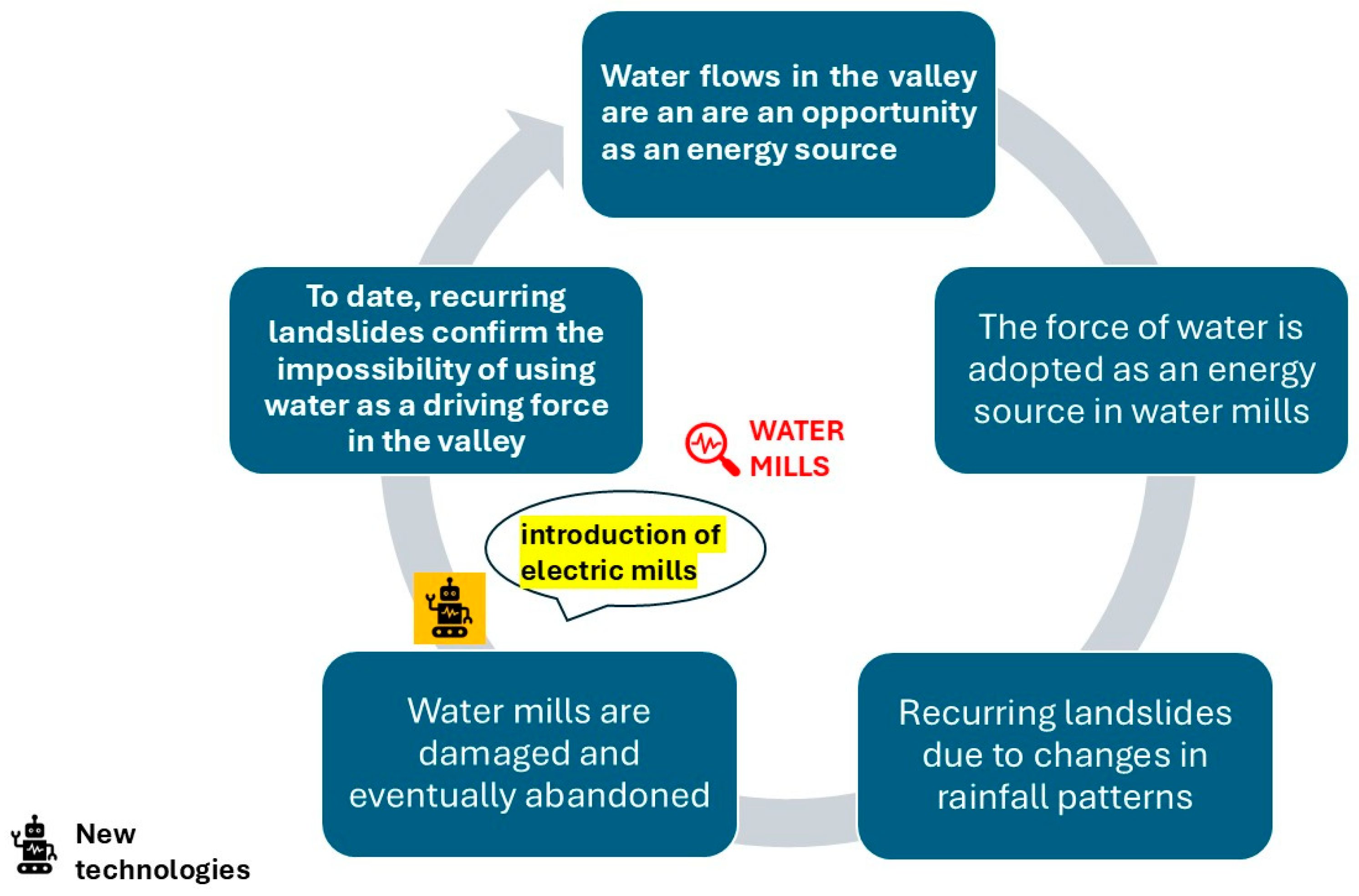

- Water: irrigation of crops and use as an energy source. In both cases, they are managed through the construction of dedicated structures: aqueducts, wells and canals in the first case and water mills in the second.

- The first phase refers to the initial climatic conditions: sometimes climate was an obstacle for the productive process, sometimes it was simply an opportunity to be exploited.

- The second refers to the construction of food-related architecture that managed those climatic conditions, either by removing obstacles to production or by optimizing the opportunities provided.

- The third refers to the most critical phase of this process, the change in the initial climatic conditions.

- The fourth refers to the decommissioning of food-related architecture as an effect of changes in initial climatic conditions.

- The fifth refers to current climatic conditions: when data on historical climate change are not available or cannot be cross-referenced and correlated with the abandonment of the structures under examination, even current climatic conditions, when compared with the characteristics of historical architecture, can reveal the changes in the climate that have taken place.

2.2. Mediterranean Diet Pyramid and the Rural Cultural Landscape in Italy

3. Results and Discussion

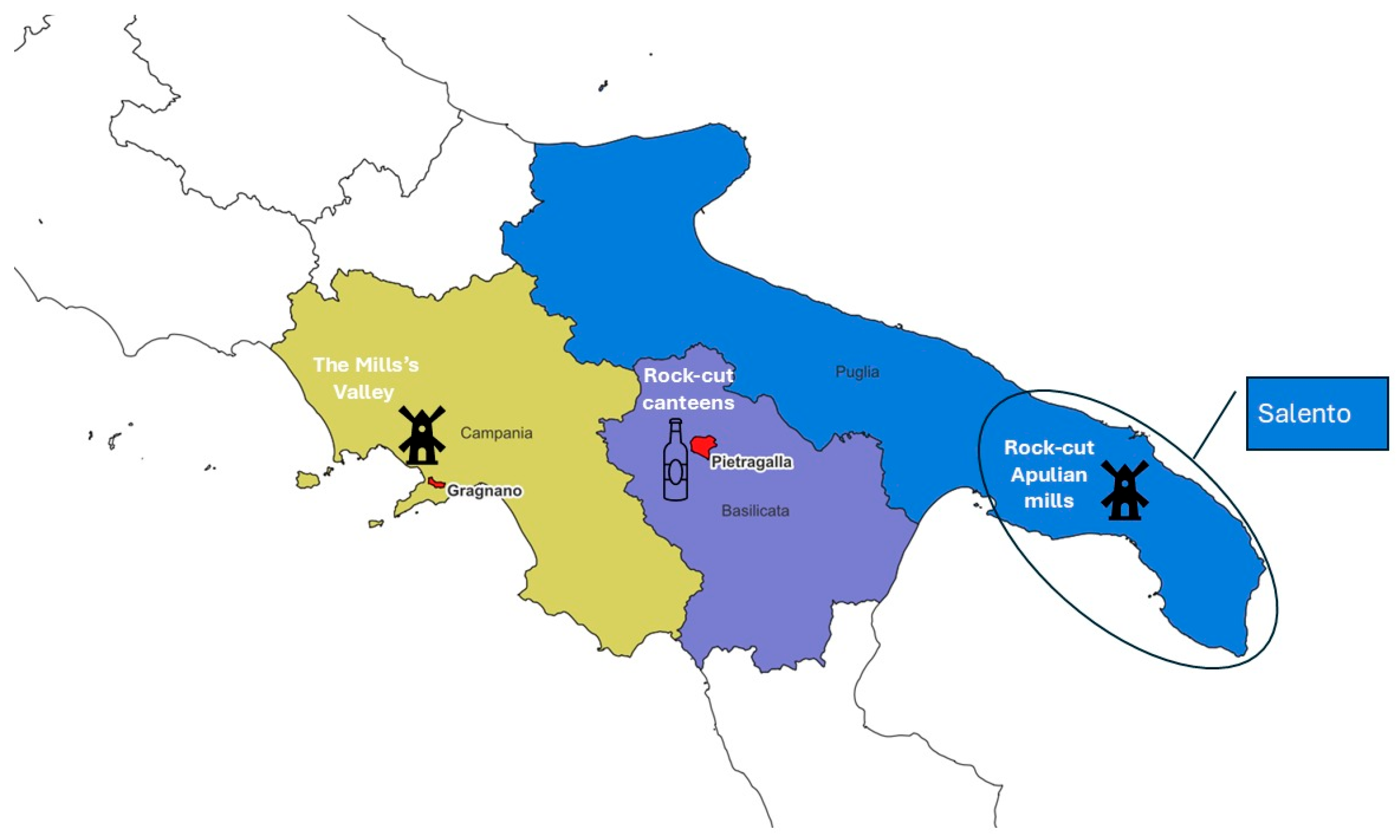

3.1. Italian Case Studies: Wine Canteens, Olive and Wheat Mills

- Their adoption in the production of three food specialties listed in the UNESCO Mediterranean Diet in Italy, all inscribed at the base of the pyramid: olive oil, local wine and cereals;

- Significance within the local cultural landscape and as elements of local intangible and tangible cultural heritage but not included in the Italian List of Cultural Assets [27];

- Decommissioning as an effect of climatic changes;

- Significant connections with climatic issues: potential as climatic indicators;

- Potential in brand marketing for local productions or/and rural regeneration projects [28].

3.1.1. Pietragalla and Its Wine District

- Relationship between rural historical architecture, cultural landscape and its changes as an effect of climatic changes: The adoption of outputs of environmental history research in the enhancement of rural cultural assets.

- History of resilience in agriculture: Valuable examples from Italian traditional cropping can be connected to the storytelling of this cultural asset.

- Enhancement of intangible values: traditional rituals, festivals, lyrics and costumes connected to the history of rock-cut canteens.

- Elements of social issues: sharing workspaces and tools in historical rural villages.

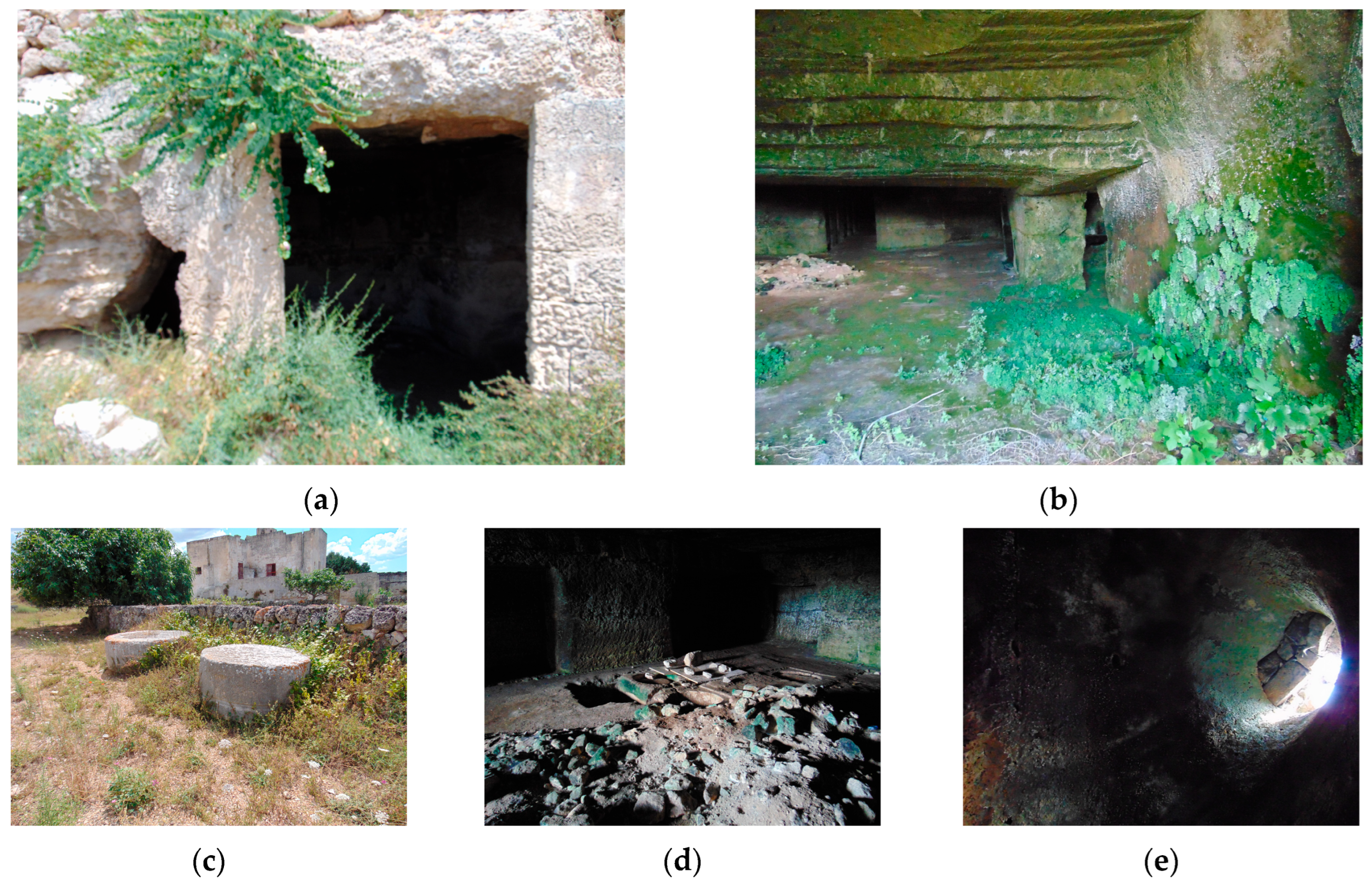

3.1.2. Olive Oil Architecture: Rock-Cut Apulian Mills

- Introduction to the small-scale Ice Age (1590–1850): effects on crops and on production;

- The transition from animal power to mechanical power in the operation of rural machineries;

- Tangible values of rural rock-cut architecture;

- Intangible values associated with the use of rock-cut mills, the role of women, children and animals and related rural rituals.

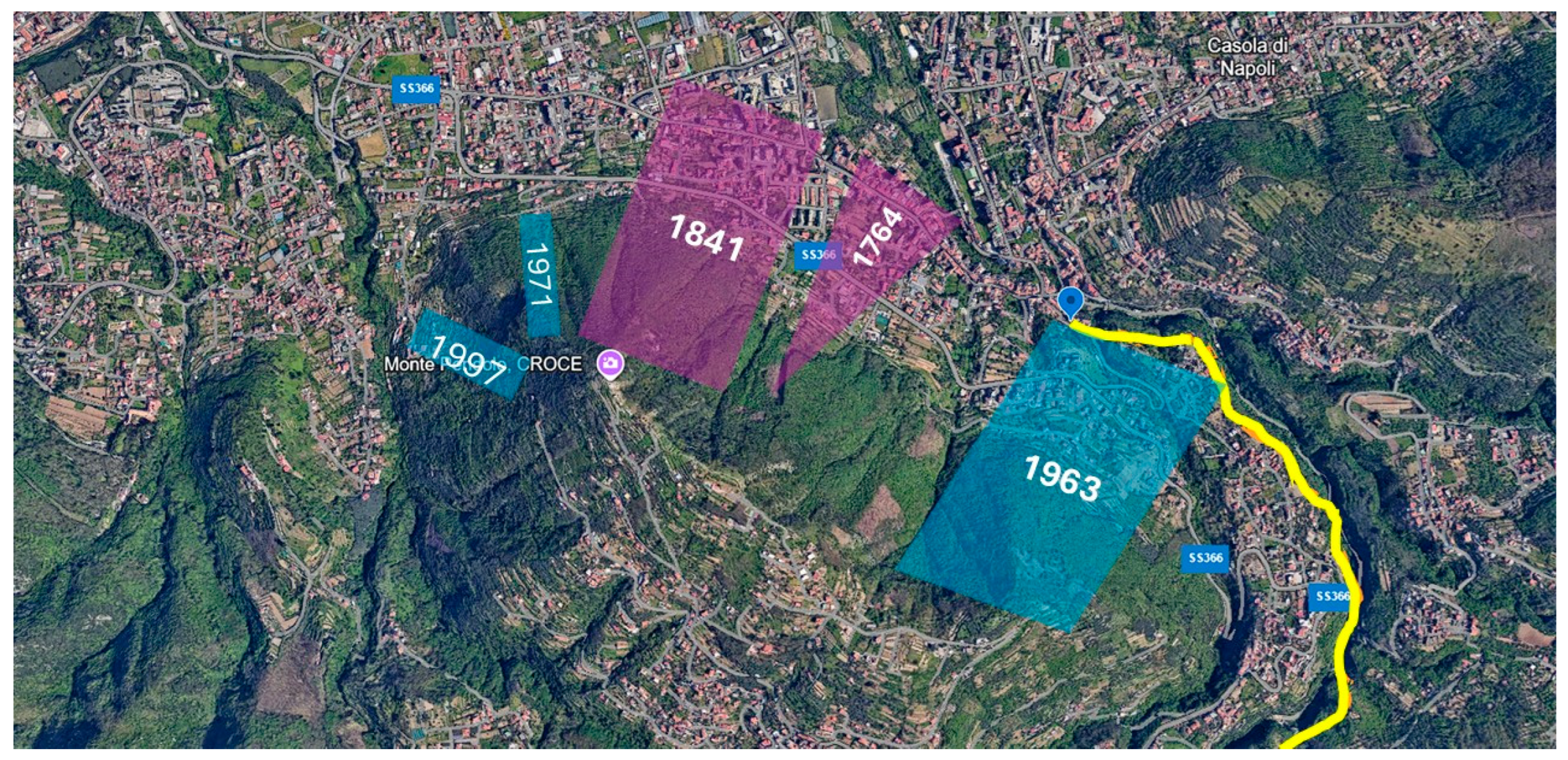

3.1.3. The Mills’s Valley in Gragnano

- Climate change and territorial vulnerability;

- Risk monitoring and control;

- Inclusion in the environmental history network of climate change-related disasters: floods, droughts, landslides, etc.;

- Resilience to climate change: relocation and transformation of productive districts.

3.2. Discussion

- Climate indicators can be a gateway to climate change issues and enrich the storytelling of the corresponding cultural assets;

- Climate indicators can enable the creation of dedicated networks;

- Climate integrators can provide access to additional tangible and intangible values.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mediterranea Diet. UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Roigé, X.; Frigolé Reixach, J. Constructing Cultural and Natural Heritage: Parks, Museums and Rural Heritage; Institut Català de Recerca en Patrimoni Cultural: New Delhi, India, 2010; pp. 1–233. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux, B.R.; Kininmont, L.E. Tourism and heritage are not strangers: A study of opportunities for rural heritage museums to maximize tourism visitation. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlikowska-Piechotka, A.; Lukasik, N.; Ostrowska-Tryzno, A.; Sawicka, K. The rural open air museums: Visitors, community and place. Eur. Countrys. 2015, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Henke, R. Recent trends in agri-food Made in Italy exports. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P. (Ed.) The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Luino, F.; Barriendos, M.; Gizzi, F.T.; Glaser, R.; Gruetzner, C.; Palmieri, W.; Porfido, S.; Sangster, H.; Turconi, L. Historical data for natural hazard risk Mitigation and land use planning. Land 2023, 12, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.D. Ecology and Environment; Rastogi Publications: Meerut, India, 2009; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, G. Snow and Ice in Antiquity. Supply, Preserving, Trade, Consumption. In Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World, Proceedings of the 19th International Classical Archaeology, Cologne-Bonn, Germany, 22–26 May 2018; Heidelberg University: Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, O.; Kumar, A. Historical Review and Recent Trends in Solar Drying Systems. Int. J. Green Energy 2013, 10, 690–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.; Sarkar, S.; Sethi, L.N. Solar Drying Technology for Agricultural Products: A Review. Agric. Rev. 2024, 45, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderhaug, T. Stockfish Production, Cultural and Culinary Values. Food Ethics 2020, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltin, E.; Jonsson, L. Cod Heads, Stockfish, and Dried Spurdog: Unexpected Commodities in Nya Lödöse (1473–1624), Sweden. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2018, 22, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzi, S.; Bertolin, C.; Diodato, N. Snowfall time-series reconstruction in Italy over the last 300 years. Holocene 2014, 24, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzyczny, K.M.; Rius, M.; Williams, S.T.; Fenberg, P.B. The ecological and evolutionary consequences of tropicalisation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covey, R.A. Kinship and the Inca imperial core: Multiscalar archaeological patterns in the Sacred Valley (Cuzco, Peru). J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2015, 40, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issar, A.S.; Zohar, M. The impact of climate changes on the evolution of water supply works in Jerusalem. In Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia; Angelakis, A.N., Mays, L.W., Koutsoyiannis, D., Mamassis, N., Eds.; IWA publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Naureen, Z.; Dhuli, K.; Donato, K.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Bertelli, M. Foods of the Mediterranean diet: Tomato, olives, chili pepper, wheat flour and wheat germ. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63 (Suppl. 3), E4. [Google Scholar]

- Saulle, R.; La Torre, G. The Mediterranean Diet, recognized by UNESCO as a cultural heritage of humanity. Ital. J. Public Health 2010, 7, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G. The tenth anniversary as a UNESCO world cultural heritage: An unmissable opportunity to get back to the cultural roots of the Mediterranean diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Faig, A.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Reguant, J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Dernini, S.; Medina, F.X.; Battino, M.; Belahsen, R.; Miranda, G.; et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; De Pergola, G. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A proposal for Italian people. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4302–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carluccio, M.A.; Siculella, L.; Ancora, M.A.; Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Storelli, C.; Visioli, F.; Distante, A.; De Caterina, R. Olive oil and red wine antioxidant polyphenols inhibit endothelial activation: Antiatherogenic properties of Mediterranean diet phytochemicals. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.A. Should we remove wine from the Mediterranean diet? A narrative review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrò, F.; Cassalia, G.; Tramontana, C. The mediterranean diet as cultural landscape value: Proposing a model towards the inner areas development process. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Catalogo Generale Beni Culturali. Available online: https://catalogo.beniculturali.it/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Varriale, R.; Ciaravino, R. Food Architecture as Drivers for the Enhancement of Local Specialties and Sustainable Rural Regeneration. In World Heritage and Food to Feed; Gambardella, C., Ed.; Napoli-Capri (Italy), Gangemi Editore spa: Roma, Italy, 2025; pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Comune di Pietragalla. Available online: https://www.comune.pietragalla.pz.it/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).[Green Version]

- Parco Urbano dei Palmenti: Memoria e cultura del fare. Available online: https://patriadellabellezza.it/atlante-di-bellezza/parco-urbano-dei-palmenti-a-pietragalla-memoria-e-cultura-del-fare (accessed on 3 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Bixio, A.; Cardinale, T.; Damone, G. L’analisi per il recupero dell’architettura per sottrazione in Basilicata. Il caso di Pietragalla in provincia di Potenza. In Quale Sostenibilità Per Il Restauro? Marghera Venezia: Venice, Italy, 2014; pp. 315–325.[Green Version]

- Varriale, R. Underground Built Heritage. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardell, M.F.; Amengual, A.; Romero, R. Future effects of climate change on the suitability of wine grape production across Europe. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Sgubin, G.; Bois, B.; Ollat, N.; Swingedouw, D.; Zito, S.; Gambetta, G.A. Climate change impacts and adaptations of wine production. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.V. Climate, grapes, and wine: Structure and suitability in a changing climate. In XXVIII International Horticultural Congress on Science and Horticulture for People (IHC2010): International Symposium on the 931; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Irimia, L.M.; Patriche, C.V.; Quenol, H.; Sfîcă, L.; Foss, C. Shifts in climate suitability for wine production as a result of climate change in a temperate climate wine region of Romania. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 131, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimia, L.M.; Patriche, C.V.; Roșca, B. Climate change impact on climate suitability for wine production in Romania. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 133, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raincaldo, P. In Basilicata le Vigne Salgono in Quota per Sopravvivere, La Repubblica. 7 March 2024. Available online: https://www.repubblica.it/green-and-blue/2024/03/07/news/in_basilicata_le_vigne_salgono_in_quota_per_sopravvivere-422256190/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Candiago, S. An ecosystem service approach to the study of vineyard landscapes in the context of climate change: A review. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disciplinare Chianti Classico. Available online: https://www.chianticlassico.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/disciplinare-Chianti-Classico.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- The System of the Ville-Fattoria in Chianti Classico. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6654/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Moriondo, M.; Van Ierland, E.C.; Trombi, G.; Bindi, M. A model-based assessment of adaptation options for Chianti wine production in Tuscany (Italy) under climate change. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Pietragalla, Recupero e Valorizzazione del Parco Urbano dei Palmenti. Available online: https://patrimonioculturale.regione.basilicata.it/rbc/upload/file_1456395002154.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- FAI. I Luoghi del Cuore. Il Parco Urbano dei Palmenti. Available online: https://fondoambiente.it/luoghi/parco-urbano-dei-palmenti?ldc (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Uylaşer, V.; Yildiz, G. The historical development and nutritional importance of olive and olive oil constituted an important part of the Mediterranean diet. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahrburg, U.; Kratz, M.; Cullen, P. Mediterranean diet, olive oil and health. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2002, 104, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, F.; Ventrella, A.; Casiello, G.; Sacco, D.; Catucci, L.; Agostiano, A.; Kontominas, M.G. Instrumental and multivariate statistical analyses for the characterisation of the geographical origin of Apulian virgin olive oils. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Loreto, M.V.; Lago-Olveira, S.; Di Noia, N.; Vollero, L.; Pennazza, G.; Santonico, M.; González-García, S. A Comprehensive Environmental Analysis of Olive Oil Production in Apulia, Italy. Food Bioprod. Process. 2025, 151, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, A. Le macchine in uso nei processi storici di produzione dell’olio. Patrim. Ind. 2009, 4, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Margiotta, S.; Martellotta, M.; Parise, M. Inventory and analysis of underground oil mills in the territory of Lecce (Apulia, southern Italy). In Proceedings of the International Congress of Speleology in Artificial Caves, Dobrich, Bulgaria, 20–25 May 2019; Zhalov, A., Gyorev, V., Delchev, P., Eds.; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Margiotta, S.; Martellotta, M.; Parise, M. Archeologia industriale e geologia: Proposta di recupero dei frantoi ipogei di Lecce. In Geologia dell’Ambiente; ITA: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Varriale, R. Southern underground space: From the history to the future. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Speleology in Artificial Cavities, Central Anatolia, Turkey, 6–10 March 2017; Parise, M., Galeazzi, C., Bixio, R., Yamac, A., Eds.; Dijital Düşler: Istanbul, Hypogea, 2017; pp. 548–555. [Google Scholar]

- Monte, A. dell’olio. In Itinerari di Archeologia Industrial nel Salento; Edizioni del Grifo: Lecce, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Monte, A. Recupero e conservazione dei trappeti ipogei del Salento. In Proceeding of the Congresso Nazionale ICIIC, Matera, Italy, 10–12 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Osservatorio Geofisico di Modena. Available online: https://www.ossgeo.unimore.it/temi-ambientali/la-serie-storica-di-temperatura/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Pennetta, L. Caratteri ed evoluzione dei litorali pugliesi in relazione al clima del passato. Geol. Territ. 2007, 3–4, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Il Cambiamento Climatico e le Nuove Sfide Dell’ovicoltura. Available online: https://oleario.crea.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Il-cambiamento-climatico-e-le-nuove-sfide-per-l_olicoltura.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Stazione RRQA Meteo Galatina (LE). Available online: https://dati.puglia.it/ckan/dataset/dati-meteo-rrqa-2024/resource/875561dd-c213-4a48-bccd-703f975fa31f?inner_span=True (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- FAI. Frantoio Ipogeo di Spongano. Available online: https://fondoambiente.it/luoghi/frantoio-ipogeo-di-spongano (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Porceddu, E. Durum wheat quality in the Mediterranean countries. Durum Wheat Qual. Mediterr. Reg. 1995, 22, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Royo, C.; Soriano, J.M.; Alvaro, F. Wheat: A crop in the bottom of the Mediterranean diet pyramid. In Mediterranean Identities-Environment, Society, Culture; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, R.L. Power from Wind: A History of Windmill Technology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- La Valle dei Mulini. Available online: https://www.valledeimulinigragnano.it/post/la-valle-dei-mulini (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- La Valle dei Mulini di Gragnano. Available online: https://www.valledeimulinigragnano.it/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Ceniccola, G. Water architecture’ and cultural identity. The Valley of the mills in Gragnano. In La Baia di Napoli; Aveta, A., Marino, B.G., Amore, R., Eds.; Artstudiopaparo s.r.l.: Naples, Italy, 2017; pp. 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenito, P. Progetto Unico??? Available online: https://www.valledeimulinigragnano.it/post/progetto-unico (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Del Prete, S.; Mele, R. The historical landsliding as an useful mean to evaluation the landslide hazard. An example in the Gragnano area (Campania). Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1999, 118, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, A.; Boulariah, O. Long-term regional changes in inter annual precipitation variability in the Campania Region, Southern Italy. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 148, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifrodelli, M.; Corradini, C.; Morbidelli, R.; Saltalippi, C.; Flammini, A. The influence of Climate Change on Heavily Rainfalls in Central Italy. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 15, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, M.; Pirone, M.; Urciuoli, G. Modellazione Numerica dell’Innesco di Debris Flows: Un caso in Campania. In X Incontro Annuale dei Giovani Geotecnici; Ceccato, F., Rosone, M., Stacul, S., Eds.; Associazione Geologica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2021; pp. 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Caloiero, T.; Coscarelli, R.; Ferrari, E. Application of the Innovative Trend Analysis of Rainfall Anomalies in Southern Italy. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 4971–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, L.; Tufano, R.; Capozzi, V.; Budillon, G.; Di Muro, C.; Esposito, L.; Forte, G.; Vitale, E.; Calcaterra, D. A postwildfire debris flood in Gragnano, southern Italy, on 11 September 2024. Landslides 2025, 22, 1923–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Riso, R.; Budetta, P.; Calcaterra, D.; Santo, A.; Del Prete, S.; De Luca, C.; Di Crescenzo, G.; Guarino, P.M.; Mele, R.; Palma, B.; et al. Fenomeni di instabilità dei Monti Lattari e dell’area Flegrea (Campania): Scenari di suscettibilità da frana in aree-campione. Quad. Geol. Appl. 2004, 11, 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Autorità di Bacino Distrettuale dell’Appennino Meridionale è con Comune di Gragnano per la Mitigazione del Rischio Idrogeologico del Territorio. Available online: https://www.matesenews.it/autorita-di-bacino-distrettuale-dellappennino-meridionale-e-con-comune-di-gragnano-per-la-mitigazione-del-rischio-idrogeologico-del-territorio/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Servizio Difesa del Suolo. Available online: https://www.comune.gragnano.na.it/it/struttura/servizio-difesa-del-suolo (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Autorità di Bacino Distretto dell’Appennino Meridionale, Decreto 226/12 April 2023. Available online: https://www.distrettoappenninomeridionale.it/oldsite/images/_AT/PROVVEDIMENTI/2023/SG/Decreto%20n.%20226%20del%2012_04_2023%20-%20schema%20di%20Accordo%20di%20Collaborazione%20AdB%20Distrettuale%20e%20Comune%20di%20Gragnano%20-%20decreto%20di%20nomina%20gruppo%20di%20lavoro.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Gragnano, Città della Pasta. Available online: https://www.agi.it/cronaca/news/2023-09-08/gragnano-citta-pasta-22944680/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Pasta di Gragnano, l’IGP fa Raddoppiare le Imprese. Available online: https://www.qualivita.it/news/pasta-di-gragnano-ligp-fa-raddoppiare-le-imprese/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Consorzio di Tutela della Pasta di Gragnano IGP. Available online: https://www.consorziogragnanocittadellapasta.it/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Sicignano, C. Memories of Stone Among the Water Ways: The Mills Valley in Gragnano, Naples. In INTBAU International Annual Event. Cham; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1030–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ruocco, G.; Sicignano, E.; Galizia, I. Strategy of sustainable development of an industrial archaeology. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ruocco, G.; Sicignano, E.; Galizia, I. Riconoscere e rivalorizzare la valle dei mulini di Gragnano. In Il Paese che Vorrei 2.0/The Town I Would 2.0; INU Edizioni srl: Roma, Italy, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Malangone, V. Valutazioni multi-metodologiche per il Paesaggio Storico Urbano: La Valle dei Mulini di Amalfi. BDC. Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2014, 14, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ruocco, I. A political concept for the Gragnano Valley of Mills (Valle dei Mulini). Urban redevelopment of cultural-industrial heritage. Urban Resil. Sustain. 2023, 1, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verazzo, C.; Ruocco, G. Il paesaggio culturale della valle dei mulini di Gragnano. Temi di storia e restauro. In La Baia di Napoli. Strategie Integrate per la Conservazione e la Fruizione del Paesaggio Culturale; ArtstudioPaparo srl: Roma, Italy, 2017; pp. 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- FAI. I Luoghi del Cuore. La Valle dei Mulini di Gragnano. Available online: https://fondoambiente.it/luoghi/valle-dei-mulini-gragnano?ldc&fbclid=IwAR0fWM7KIDgCbMT8L5SGW-2OF3R7xbVsfTgjKtNLWchAP3PGvsrcHdV8JGU (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- CAI. Monti Lattari. Available online: https://www.caimontilattari.it/sentiero/332/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- SMA. Campania. Available online: https://www.smacampania.info/cantiere-di-valle-dei-mulini-gragnano/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Varriale, R.; Ciaravino, R. Underground Built Heritage and Food Production: From the Theoretical Approach to a Case/Study of Traditional Italian “Cave Cheeses”. Heritage 2022, 5, 1865–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rete Rurale. Available online: https://www.reterurale.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/1 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- FEASR. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/IT/legal-content/summary/european-agricultural-fund-for-rural-development-eafrd.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

| Name | Focus Points for Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Porta Castello di Sopra Mill | Location beside one of the gates of the Castle Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: Connection to the castle |

| Lo Monaco Mill |

|

| Forma Mill | The most ancient mill of the valley, built immediately below the spring. Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: the beginning of the history of the Valley and of the district |

| Grasso Mill | Accessible only from the stream bed Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: reshaping the natural river |

| Scomparso Mill | Accessible only from the stream bed Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: reshaping the natural river |

| Porta Castell di Sotto Mill | Accessible only from the stream bed Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: reshaping the natural river |

| Scola Mill | Several historical renovations Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: historical reuses and stratifications |

| La Fusara Mill |

|

| La Mena Mill | Two towers: the first in tuff, the second in limestone like the main building Potential added value for the interpretation of the Mills’s Valley: different materials |

| Santa Lucia Mill |

|

| Grotticella Mill |

|

| La Pergola Mill |

|

| Type | Case Study | Food Connected | Climatic Issue Connected | Type of Management | Region | Period | Climatic Change | Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Water Mills | Mills’s Valley | Durum wheat | Water | Adoption as an energy source (regular water force) | Campania | 13th/20th | Recurrent floods of the Vernotico river due to climatic changes (see Figure 17) | Yes (public) |

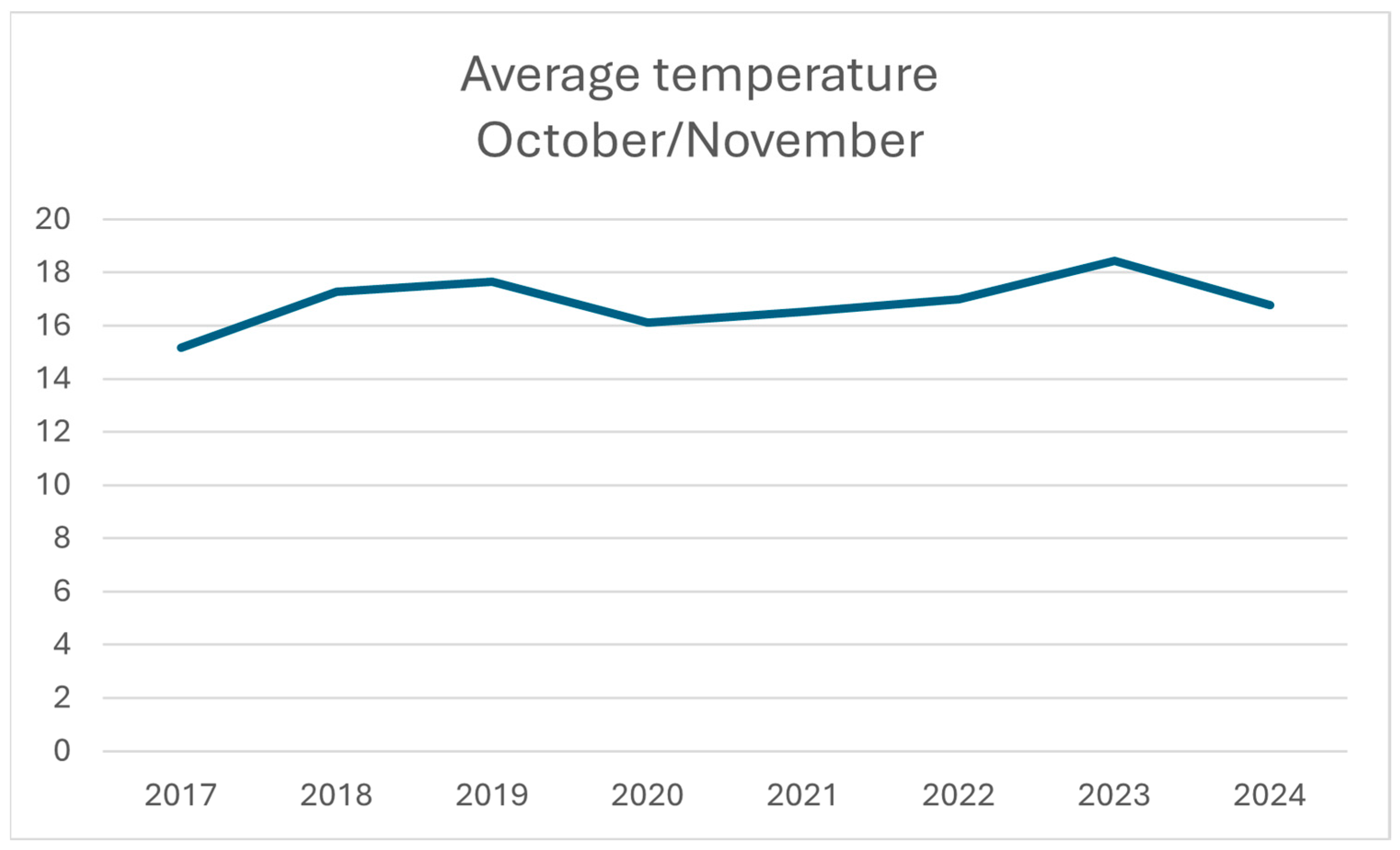

Olive Oil Mills  | Apulian Underground Mills (diffused) | Olive oil | Temperature | Optimization of temperature for fluidification (18 °C minimum) | Apulia | 15th/20th | Rising winter temperatures due to the passage from “small glacial era” to “temperate climate, confirmed by current values (see Figure 12) | Some (mostly private properties) |

Pietragalla Canteen | Pietragalla Wine District | Wine | Temperature | Logistics (canteens were just between the yards and the village)/internal climate | Basilicata | 16th/20th | Increase in cultivation quota due to increase in temperatures (up to 800 m. a.s.l.) | Yes (public/private) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varriale, R.; Ciaravino, R. Climate Change and Historical Food-Related Architecture Abandonment: Evidence from Italian Case Studies. Heritage 2025, 8, 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100423

Varriale R, Ciaravino R. Climate Change and Historical Food-Related Architecture Abandonment: Evidence from Italian Case Studies. Heritage. 2025; 8(10):423. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100423

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarriale, Roberta, and Roberta Ciaravino. 2025. "Climate Change and Historical Food-Related Architecture Abandonment: Evidence from Italian Case Studies" Heritage 8, no. 10: 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100423

APA StyleVarriale, R., & Ciaravino, R. (2025). Climate Change and Historical Food-Related Architecture Abandonment: Evidence from Italian Case Studies. Heritage, 8(10), 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100423