Abstract

This study presents the first systematic investigation of ancient Egyptian votive animal mummy wrappings, based on the analysis of an extensive dataset encompassing specimens from various museum collections and archaeological contexts. The research addresses the long-standing neglect and fragmented understanding of the wrapping chaîne opératoire and aims to establish a consistent terminology, as the different stages of the wrapping sequence, bundle shapes, and decorative patterns have often been described vaguely. Through an interdisciplinary methodology that integrates photogrammetry, colorant identification, textile analysis, and experimental archaeology, the study explores the complexity of wrapping practices across their different stages. This approach offers new insights into the structural logic, raw material selection, and design conventions behind this production. The analysis reveals that the bundles exhibit standardized shapes and decorative patterns grounded in well-established visual criteria and manufacturing sequences. These findings demonstrate that the wrappings reflect a codified visual language and a high level of technical knowledge, deeply rooted in Egyptian tradition. The study also emphasizes its economic implications: the wrapping significantly enhanced the perceived value of the offering, becoming the primary element influencing both its material and symbolic worth. Ultimately, this work provides an interpretative framework for understanding wrapping as an essential medium of ritual sacralization for votive animal mummies, allowing the individual prayer to be effectively conveyed to the intended deity. Consequently, this research marks a significant step forward in advancing the technical, aesthetic, and ritual insight of wrapping practices, which preserve a wealth of still-overlooked information.

1. Introduction

Animals held a pivotal and multifaceted role in ancient Egyptian culture, religion, and worldview. They were regarded as potential vessels of divine presence, embodying aspects of certain gods. By closely observing the natural behaviors and distinctive traits of various species, the Egyptians discerned analogies with the characteristics, powers, and abilities of specific deities. As a result, certain animals gradually came to serve as manifestations through which divine presence could be accessed, worshiped, and materially represented. As far back as the Predynastic Period (ca. 4000/3900–3300 BCE), there is evidence, though sporadic, of practices that reflect the symbolic and religious roles attributed to animals within Egyptian belief. During this time, animals were occasionally interred either in association with human burials or in independent graves [1,2]. While animal burials are attested from the earliest periods, the deliberate mummification of animals as part of religious practice began only in the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 BCE) [3,4]. However, it was during the 1st millennium BCE, particularly from the Third Intermediate Period through to the Roman Period (ca. 1069 BCE–4th century CE), that this phenomenon reached an unprecedented scale and complexity, developing into a vast and organized ritual economy. In this period, millions of animal mummies were prepared and deposited at sacred necropoleis throughout Egypt. Among them, some served as votive offerings to be dedicated to their divine counterpart. Although the animals used to produce these ex-votos, known as votive animal mummies, were not inherently sacred, they were nevertheless regarded as the living hypostases of specific deities. Particularly during major religious festivals, these animals were mummified to meet the growing demand from worshippers, who purchased and offered them at the temple of the deity to whom they were devoted, in hopes of securing divine favor [5]. These votive offerings ensure that the pilgrim’s message reached the deity directly. In fact, through the process of mummification, these creatures were ritually transformed into an Osiris and were no longer regarded as merely preserved bodies, but as the ba (soul) of the deity with which their species was associated [6]. Like human souls, the ba of these animals was believed to retain mobility between the earthly and divine worlds, thereby acting as an intermediary in charge of conveying pilgrims’ prayers, requests, and complaints directly to the gods, eliciting divine attention and, potentially, divine intervention. As a result, votive animal became conduits for communication between the human and divine worlds [5]. During the mummification process, the ritual transformation of these offerings was accomplished through the act of wrapping. While ancient Egyptian written and iconographic sources are notably reticent on mummification practices, the few documents that do address the subject tend to omit descriptions of bodily manipulation, focusing instead on the wrapping process [7,8,9]. This selective silence appears to be intentional. Indeed, the act of wrapping was not merely protective, but generative: through the ritual use of textiles and specific techniques, the animal was transformed into a sacred being of cultic and ontological significance. The material act of wrapping concealed the body and, in doing so, evoked a divine condition: just as the gods themselves are often described as clothed, veiled, or hidden, so too was the wrapped animal body rendered sacred by its concealment. Moreover, wrapping also functioned to mold an idealized version of the animal’s form, a material simulacrum that transcended the physical aspect and embodied sacred essence [10]. This helps explain the geometric forms of many votive animal mummies. Their shapes appear to correspond to established aesthetic conventions, possibly linked to specific species (see below). These visual criteria would have been readily recognizable to an Egyptian audience, encoding both species identity and divine association within a formalized visual language that remains partially intelligible up to the present day. As a result, the offering assumed a form that was immediately identifiable to both the donor and the deity to whom it was dedicated.

From this perspective, the widely debated phenomenon of fake/false/amalgam/pseudo-mummies, namely bundles that are either empty or contain only partial animal remains (such as fur, feathers, or bones), multiple individuals or parts thereof, species inconsistent with the external form, or even non-animal matter (e.g., vegetable matter, mud, or stones), ought to be reinterpreted (see below). Even in the absence of an animal body, the textile shell functioned as the true medium of transformation, enabling the offering to be ritually activated in much the same way as other wrapped, ritually charged materials [10]. In light of this, the wrapping emerges as the principal agent in shaping both the material form and the ritual function of these objects.

Yet, both wrapping and the use of textiles as ritual media has received long-standing marginalization within Egyptological research. Although some studies have focused on the wrappings of votive animal mummies, they have generally been restricted to visual analyses of limited samples drawn from specific cemeteries, collections, and/or animal species [11,12,13,14,15,16].

The present study offers a detailed analysis of the techniques employed in the wrapping of votive animal mummies, tracing the process from the initial shaping of the bundle to the final arrangement of outer strips to produce distinctive decorative patterns. Although it does not aim to be exhaustive, this work contributes significantly to our understanding of the material practices involved in the preparation of these ritual objects, shedding light on the technical choices, aesthetic strategies, and symbolic considerations that shaped the external appearance of votive animal mummies.

2. Material and Methods

The absence of evidence documenting the wrapping practices and the identity of the craftspeople behind this workmanship leaves us with a single primary source of information: the mummies themselves. To date, scholarly efforts to investigate this category of artifacts have remained limited to selected groups of mummies examined through visual inspection. While this continues to serve as a valuable research starting point, innovative non-destructive diagnostic techniques now allow researchers to thoroughly investigate the specific stages of the wrapping chaîne opératoire, from the shaping of the bundle to the construction of the outermost decorative patterns. This enables a more nuanced understanding of the technical logic and semantic distinctions embedded in the materiality of votive animal mummies.

The present study is grounded in an interdisciplinary approach that combines several of these advanced technologies. Developed within the framework of the MSCA-funded SEAMS project, this methodology was used to systematically document every aspect of the wrapping process, including textile weaving, coloring, and pattern construction, across a broad sample of votive animal mummies held in twenty museum collections worldwide.

The decision to investigate a wider range of animal species stems primarily from the observation that no single shape or decorative pattern appears to be exclusive to one species. Moreover, no known sources explicitly indicate that workshops specialized in producing mummies of a single animal species. Sacred cemeteries dedicated to the animal manifestations of a city’s deity often housed multiple species of mummies, likely produced in the same workshops. A systematic analysis of how shapes, patterns, and anatomical features were rendered across different species thus ensures a more balanced and meaningful dataset.

Limiting the study of votive animal mummy wrappings to a single museum collection would also risk reducing the analytical scope to a narrow subset of production contexts. Indeed, museum collections typically include specimens originating from a limited number of archaeological sites, often found during archaeological fieldwork affiliated with the institution. Bundles acquired through subscription, often granted in return for financial contributions to excavations campaigns, generally derive from a limited number of archaeological contexts. Mummies donated or directly purchased by museums are frequently unprovenanced or linked to vague or misleading attributions. Therefore, broadening the corpus under study to a multi-collection dataset allowed the inclusion of specimens originating from different necropoleis across Egypt. This enables a country-wide comparative analysis of the tangible traces of regional and time-specific workshop practices, the identification of stylistic trends, and the documentation of variations in wrapping techniques.

To this end, a digital investigation grounded on image-based modeling was carried out to achieve both geometric precision and high-resolution detail in the resulting 3D models of the mummies. This significantly enhanced the legibility of their intricate wrapping patterns, whose fine details are often difficult to discern through traditional visual inspection due to the overlapping and interlacing of textile strips, as well as the poor preservation of certain specimens. The disabling of uniform coloring and the virtual unwrapping of the mesh allowed the extraction of the elaborate geometric features of the decorative designs and the subsequent creation of accurate line drawings that enable a more detailed analysis of wrapping structures and techniques. A further step in this direction involved the acquisition of linear and geodesic measurements from the 3D models, enabling a detailed morphometric analysis of the overall dimensions, proportions, volumes, and geometries of both the bundles and the wrapping patterns decorating their outer surfaces. This cutting-edge approach yields more robust and meaningful data than any form of two-dimensional visual inspection, as it fully accounts for the complexity and visual impact of the decorative modules.

Additional insight into the original wrapping designs, and, by extension, their manufacturing techniques, was gained through the analysis of the nature and spatial distribution of coloring materials present on the strips. Often, sophisticated decorative patterns and anatomical features were achieved by interlacing naturally colored linen with bleached, dyed, or painted strips, creating striking visual contrasts. Degradation over time, primarily caused by bleaching agents used to enhance dye absorption, as well as various mordants, particularly iron-based compounds, alongside the natural fading of textiles and the presence of surface soiling, often compromises the identification of the original colors and, consequently, the accurate interpretation of the decorative pattern as it was originally conceived [17]. The non-invasive protocol applied in the present study combines multispectral imaging (MSI) techniques with fiber optic reflectance spectroscopy (FORS), enabling the accurate identification of colorants while avoiding micro-invasive sampling. The results of this diagnostic investigation, integrated with the analysis of pattern morphology, enabled the collection of reliable data on the original design logic, wrapping techniques, and raw material choices, and facilitated meaningful comparisons across the examined mummies [18].

Further insights into the logic behind bundle shaping and wrapping were gained through textile analysis, using non-invasive tools such as a thread counter and a digital microscope. Despite the challenges posed by the shape, size, state of preservation of the mummies, and the interlacing and overlapping of narrow strips and irregular textile pieces, it was possible to gather meaningful data regarding the textiles selected for both shaping the bundles and decorating their outer surface. Paramount information concerning the resources (e.g., fiber type and twist) and weaving aspects (e.g., weave structure, yarn dimensions, and thread density) allowed the assessment of textile texture. This aspect is frequently conflated with textile quality, an evaluative criterion that, in this context, is entirely arbitrary. The common distinction between fine and coarse textiles, often further subdivided into additional qualitative categories, is inherently problematic, as such classifications rely on relative standards that may vary significantly among archaeological contexts. Within a broad, multi-provenience, and diachronic dataset such as that of the present study, any attempt to assign quality labels would not only lack consistency, but would also be methodologically unsound. In light of this, in the present study, textile texture is understood as referring to fabric consistency and coverage, two functional criteria likely taken into account by skilled craftsmen in the strategic selection of different textiles employed at various stages of bundles construction.

The gathered data enabled a more nuanced assessment of wrapping craftsmanship, supported by the high-precision recording of reconstructed wrapping gesture sequences, performed in a dedicated facility using a motion capture system. The reproduction of recurring patterns on three-dimensional surfaces yielded significant insights, which will be comprehensively addressed in an upcoming publication. This approach brought to light the craftspeople’s technical expertise and manual dexterity, as well as the complexity, time investment, and amount of resources required for creating the wrappings. Notably, the analysis and comparison of video recordings from individual experimental sessions allowed the identification of mandatory movements involved in producing decorative designs, the documentation of different construction techniques, and the mapping of the technical stages that formed the wrapping chaîne opératoire (see below).

While attempting to describe these aspects, it became clear that the limited attention previously devoted to both human and animal mummy wrappings, resulting in fragmentary investigations on that topic, has led to the emergence of multiple terminologies, often vague, incoherent, sometimes unintelligible, and, in certain respects, entirely absent. This repeatedly underscored the urgent need to define a consistent terminology for mummy wrappings, encompassing all aspects, from construction stages and techniques to the raw materials employed and the decorative designs featured. As part of the SEAMS project, a specialized project (Terminology for Mummy Wrappings) is currently developing a precise, consistent, and semantically rich terminology for the description of both human and animal wrapping systems. The goal of this initiative is to create a standardized lexicon that will enhance research communication, promote data interoperability and reusability, and facilitate knowledge transfer through well-defined and intelligible terminology that reflects the full complexity of the wrapping systems and their manufacture. Throughout the present contribution, the terminology used adheres to the definitions developed by such a project, whose outcomes will be presented in an upcoming comprehensive publication.

The accurate and systematic approach described above laid the groundwork for a structured classification of both bundle and pattern construction techniques and overall morphology, designed to be used alongside each other, finally allowing these long-overlooked subjects to be studied within a coherent and comparative framework. This classification is based on the specimens directly analyzed within the framework of the SEAMS project, as well as on an extensive comparative review of examples from other museum collections and archaeological contexts. Far from being exhaustive or universally comprehensive, as is the case with any classification system, it represents a conceptual tool, constructed to organize and relate observed patterns according to newly acquired insights and the analytical criteria developed throughout this research.

Accordingly, the clusters presented below are not to be understood as fixed, closed, or immutable categories. Instead, they are proposed as a working framework, flexible and open to refinement, intended to aid in the description, interpretation, and understanding of the technical, aesthetic, and ritual processes that grounded the production of the elaborate decorative layouts of votive animal mummies.

3. Results

3.1. Shape and Shaping

Intact mummies have been, and continue to be, favored acquisitions for museums, largely because their visual integrity strongly appeals to the visitors. However, less preserved or damaged specimens can offer privileged access to internal features of the bundles, thereby shedding light on construction methods, textile layering sequences, and wrapping strategies that would otherwise remain hidden beneath the outermost decorative layers. In this context, the direct inspection of several poorly preserved mummies provided a valuable opportunity to acquire a broader range of information on the shaping of votive animal bundles.

Regardless of whether the bundle contained actual animal remains, the innermost section typically consists of darkened, crusty textile layers, which radiological analyses consistently reveal as radio-opaque areas [19]. The color and consistency of these layers suggest that the textiles had been soaked in resinous substances, likely intended to act as a protective coating for the animal remains when present, while in cases where no remains were included, they may have served as a structural core for shaping the bundle (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Innermost textile layers soaked in a black resin-like substance on the cat mummy MM_Salford-EA16-2.a (photo: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester).

On top of this core, a variable number of textile layers was applied. The hands-on examination of the specimens under study revealed an average of seven textile layers per mummy, excluding both the innermost core and the outermost decorative strips. The number of layers ranged from a minimum of three in the simplest specimens to a maximum of fifteen in the most elaborate examples. Radiological imaging can sometimes assist in refining these observations, though it often remains unclear whether the identified layers represent separate textile elements or repeated folds of a single cloth.

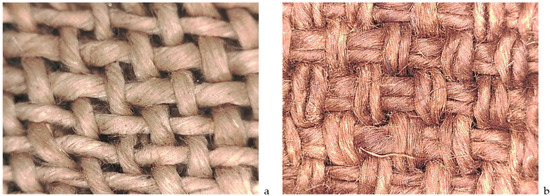

Inner textile layers analyzed were composed exclusively of flax fibers (Linum usitatissimum) with S-spun threads. The most frequently observed weave form is tabby, which was especially common in ancient Egypt [20]. It consists of horizontal threads (wefts) that pass alternately over and under each vertical thread (warp), with the binding points (i.e., where a weft crosses a warp) reversed in the next row. A variation of this structure, identified among internal textiles, is the basket weave, in which groups of weft threads are interlaced with equal numbers of warp threads (Figure 2). In all specimens examined, both weave types are warp-faced, meaning that the number of warp threads exceeds that of the weft. Thread counts vary across samples, but are consistently lower than those recorded for the outermost layers. This suggests that the texture of the internal textiles was more flexible compared to that of the outer ones. This consistency, observed across all mummies under study, suggests that the inner textiles were carefully selected for their technical and functional properties, and strategically shaped to suit their intended position within the bundle, thereby contributing to the achievement of its final shape and dimensions.

Figure 2.

Dino-Lite images showing a tabby weave on the ibis mummy (a) WM_56.22.222, and a basket weave on the ibis mummy (b) WM_42.18.5 (photos: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum).

These textiles mainly consist of irregular pieces and strips of linen, torn from various cloths that originally served different purposes. The fact that these linen scraps were in secondary use is confirmed by the identification of several weaving and stitching features, such as edges, selvedges, fringes, self-bands, seams, and stitches. Although most of these inner textiles retained their natural color, some were found to be dyed. Given that they were not intended to be visible in this context, the effort to dye them was most likely undertaken for their original purpose, further supporting the argument of their reuse.

In the most deteriorated mummies, close inspection of the layering structure revealed that inner textiles could be arranged in various ways, depending on their shape: spirally wrapped around the core, overlapped in a patchwork-like fashion, or used as larger pieces covering most of the internal surface of the bundle. These configurations could recur multiple times within a single mummy, at different stages of the layering sequence. Once suitably arranged, the textiles were secured by single linen threads wrapped around them and, in some cases, by cords, some of which were made from plant fibers. Other vegetal components, such as plant fiber strips and splints, are also attested. The former were typically used in the same way as linen threads, tightly wrapped both horizontally and vertically around each inner layer to keep it securely in place. Vegetal splints, on the other hand, were employed to model elongated shapes, such as fish or crocodile mummies. However, they have also been observed in other species, including cat mummies, where they may have served to support an upright position (Figure 3). Non-organic filling materials, such as gravel, were also used to stabilize and model the bundles.

This robust background determined both the weight and the consistency of the bundle, contributing to its final tactile effect. At the same time, these linen layers also influenced its visual appearance, as they were used to mold the shape, define the dimensions, and establish the intended orientation of the mummy.

In terms of dimensions, votive animal mummy bundles could range from just a few centimeters to several meters in length, depending not only on the size of the internal contents but also on deliberate or commissioned choices to produce bundles of specific proportions. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find that, even when a complete body enclosed, the bundle’s overall size exceeded the actual anatomical contents. This elongation typically occurred at the bottom, resulting in a total length greater than that of the skeletal remains [12].

Figure 3.

Vegetal splints used to stabilize and maintain the orientation of the cat mummy PAHMA_5-592 (photo: M. D. Pubblico, © 2024 Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California).

Figure 3.

Vegetal splints used to stabilize and maintain the orientation of the cat mummy PAHMA_5-592 (photo: M. D. Pubblico, © 2024 Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California).

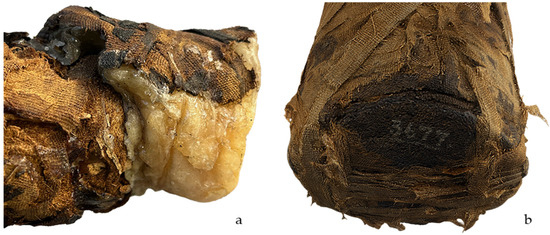

Regarding orientation, bundles could be conceived as either lying or upright. Lying bundles, typically flattened and displayed on their side, are not included in the present study. Instead, the upright mummies are those intended for vertical display, although they often lack a self-supporting structure and thus needed to be propped against a surface to remain standing. A few specimens include a built-in base: in some cases, they are made of wax and hidden beneath the outer wrappings, and in others, they consist of a wide button-shaped element of hardened textile, which rendered the bundle self-standing (Figure 4). These different orientations played a key role in determining the overall visual appearance of a bundle, which was also influenced by its shape.

Figure 4.

Different built-in bases on (a) the ibis mummy MM_6098 (photo: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester) and (b) the cat mummy CMNH_3677-4 (photo: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History).

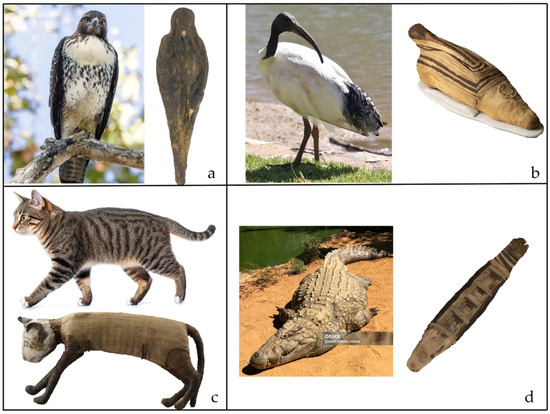

Two main shape categories have been identified: naturalistic and geometric. Naturalistic shape refers to bundles whose outer form closely reproduces the animal’s anatomy in naturalistic and recognizable postures. All major anatomical features are carefully modeled in accordance with the specific stance depicted, demonstrating a high level of intentionality and craftsmanship in wrapping manufacture. Cats, for example, are portrayed in a striding posture, with fully extended limbs and an elongated body, capturing a moment of movement in a lifelike and dynamic manner. Ibises are rendered in a seated pose, with their beaks turned backward and tucked toward the body, echoing their natural resting behavior. Crocodile mummies mirror the animal’s fully recumbent sleeping posture, as observed in the wild, with the body and head laid flat along the ground and the limbs retracted and pressed tightly against the torso, almost blending into it. Birds of prey are typically shaped with the head and tail fully extended and the wings tightly folded against the body, resembling the alert stance of a bird perched on a pole (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(a) Naturalistic shapes of bird of prey mummy CMNH_1763-3a (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History); (b) ibis mummy ME_S.11029 (photo: Museo Egizio); (c) cat mummy Louvre_E 2815 (© 2014 Musée du Louvre); and (d) crocodile mummy MM_7892 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester).

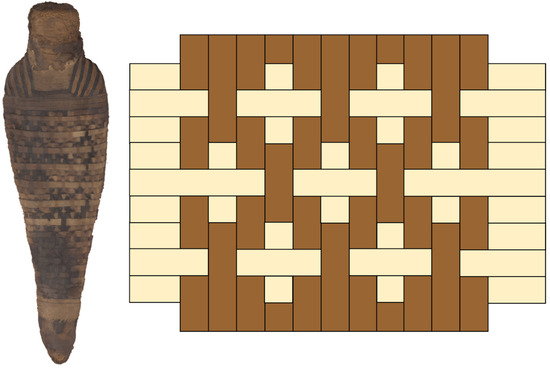

Three main geometric shapes have been distinguished: cylindrical, commonly used for cats, dogs, and snakes; conical, mostly associated with ibises and birds of prey; and circular, primarily used for shrews and snakes (Figure 6). However, while these correspondences provide a general framework, they are not strict, and a wide range of variations is attested. Irregularities in execution often resulted in more amorphous or undefined shapes. The top of conical and cylindrical-shaped mummies can feature a flat surface (e.g., NMD_7464), a rounded end (e.g., REM_RC-225), or a modeled head (e.g., PAHMA_5-586). The latter, commonly referred to as skittle-shaped mummies, may present a head rendered with either minimal or elaborated features. Some mummies feature a head with a simplified shape, lacking somatic detail or showing, at most, a slight protrusion suggesting the snout (e.g., CMNH_2983-6541). This is also the case for BM_EA15980, the only specimen in this study that presents two heads. In other instances, more elaborate facial features are observed, which may be applied, painted, or padded (see below). Hybrid forms are also attested, in which the head retains a generic shape but includes minimal anatomical elements, such as ears (e.g., BKM_X1179.3). Conical and cylindrical-shaped mummies may also feature modeled feet, crafted with particular care to most likely resemble human mummy feet rather than the foot of a coffin, as previously suggested [11]. Typical of ibis and bird of prey mummies, although also attested in other species, such as cat mummies, these feet are entirely modeled from textile fragments bound together with cords and linen threads. They may be either shaped as an integral part of the bundle (e.g., BM_EA37348) or produced separately and attached to it (e.g., MM_1981.576). Specimens with this feature often present detailed facial details (e.g., RAFFMA_EG.01.029.2007), though examples with an amorphous top are also attested (e.g., WM_42.18.5).

Figure 6.

Different geometric shapes on (a) the dog mummy MFAB_Eg.Inv.6234 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston); (b) the snake mummy ME_P.6110 (photo: Museo Egizio); and (c) the ibis mummy MM_11296 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester).

Once the bundle’s dimensions, orientation, and shape had been defined, the external pattern could then be designed in accordance with these features.

3.2. Pattern and Patterning

The often decorated outer surface of votive animal mummies is exposed to the human eye. Consequently, unlike the internal contents, which have been investigated using the most advanced technologies, this outer layer has, to date, been approached almost exclusively through direct visual inspection. Yet, ease of visual access does not necessarily equate to accurate readability. The human eye alone is often unable to fully grasp the complexity of these decorative modules. The poor condition of certain bundles, which has proven useful in the investigation of internal layering, significantly hampers the interpretation of the external designs and the identification of the techniques employed in their creation. The fading or degradation of colored strips, key elements in shaping the overall visual effect, further complicates the accurate perception of the original decorative patterns. For these reasons, direct visual inspection only served as the starting point for this study, as it often falls short of capturing the full complexity of the wrapping structures. Subtle aspects of the weave and the underlying construction logic frequently escape the naked eye also because the narrow linen strips that form the decorative patterns, are tightly interlaced and overlapped, thus obscuring the precise articulation of the design.

The interdisciplinary methodology developed for this study, which integrates a range of high-accuracy technologies, enabled the detailed reconstruction of the materiality, structure, and manufacturing techniques of the decorative patterns forming the outermost layer of votive animal mummy wrapping.

As with the inner textile layers, flax is the only fiber identified in the outer wrappings during the present investigation. The threads are almost exclusively spun in S-twist, and plain tabby accounts for nearly all of the weave structures attested, with the sole exception of one specimen (PMEA_LDUCE-UC45976), which displays a basket weave. The consistently high thread counts suggest that textiles with a higher thread density (i.e., the number of threads per square centimeter) were preferred for the outer surface, as they provided greater structural consistency and a high degree of coverage necessary to conceal the underlying layers (Figure 7). However, although this feature was consistent across all specimens analyzed in this study, the limited number of mummies examined, compared to the hundreds of thousands produced, calls for caution in asserting this as a technological constant across all votive animal mummies. Notable exceptions are attested: for instance, the specimen MHM_MME 1978_001 features a deliberate alternation between denser and looser textiles on the outer surface, likely intended to enhance visual contrast and amplify the decorative effect. This confirms that the textiles were carefully selected based on their texture.

Figure 7.

Examples of different weave structures, densities, and textures between inner and outer textiles on the ibis mummy (a) CMNH_1764-4a (photo: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History) and the cat mummy (b) AMUM_1981.1.30 (photo: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of the Institute of Egyptian Art & Archaeology of The University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, USA).

The narrow strips and irregular pieces of textile used to decorate the outer surfaces of the bundles, ripped into the desired shapes from reused cloths, still retain original weaving and tailoring elements. Indeed, even on the outer layers, original textile features such as edges, selvedges, fringes, and stitches have been identified, most notably self-bands and seams. They are often placed in prominent positions, suggesting that they were not considered unpleasant elements to be hidden (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Ibis mummy CMNH_4918-2 with a seam in a prominent position (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History).

As noted above, some of these textiles were undoubtedly dyed. Whether the dyeing process was undertaken for their original use or after repurposing to suit a specific decorative layout remains unclear and far from conclusively established. Nonetheless, several considerations arise. The presence of colored textiles among the inner layers of the bundles suggests the reuse of dyed fabrics. However, at least for the outermost layers, it is also possible that some of these reused textiles were dyed ad hoc to suit the intended aesthetic purpose. On the other hand, the reuse of already-dyed textiles may have been hampered by degradation, especially due to the use of mordanting and bleaching agents, which may have compromised their preservation and made them unsuitable for reuse. However, it is worth considering that dyeing was a time-consuming process, seemingly at odds with the large-scale production of votive animal mummies. Radiocarbon dating carried out on both the contents (animal remains) and the containers (wrappings) has revealed a slight chronological discrepancy, pointing to a swift replacement of the textiles used for wrapping [4,21]. This supports the hypothesis that dyed textiles, originally produced for other uses, were repurposed in the decoration of votive animal mummies. However, the current state of dating investigations remains limited to a few specimens, preventing any definitive conclusions from being drawn at this stage.

Alongside degradation and soiling, the perception of the original strip colors is, as previously noted, further compromised by the natural fading of the textiles over time, an effect particularly accentuated by the sensitivity of certain colorants to sunlight. The original appearance of the strips can sometimes be recovered by lifting the overlapping layers or the fabric pieces positioned along the sides of the bundles. These sections, by covering portions of the underlying strips, shielded them from light exposure and preserved their original color, in contrast to the exposed areas that underwent fiber discoloration (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Cat mummy WM_42.18.2 showing the original color of the outer strips preserved from discoloration (photo: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum).

The present study benefitted from the use of MSI techniques, which record the reflectance and absorbance properties of the organic and inorganic matters. This provided preliminary information on the nature and distribution of coloring materials present on the mummy wrappings under investigation, which subsequently guided the FORS measurements. The spectral profiles obtained show the behavior of a material to light, which is reliant on its chemical composition. As a result, this technique often yields conclusive information on the compounds used as coloring agents, thereby contributing to the reconstruction of the original wrapping designs. All the dyestuffs identified in the course of this study are plant-based. The reddish hues, ranging from bright red to pink and orange, were achieved through the use of safflower and madder. No traces of red ochre have been detected in the specimens analyzed to date. Dark strips, spanning light to dark brown tones, resulted from tannin-based dyes, with the shade varying depending on their combination with iron compounds. As for the light-colored strips, diagnostic investigations revealed no distinctive features. In such cases, sampling combined with minimally invasive analysis may be required to determine whether a yellow dye was used or if the shade corresponds to the natural color of flax fibers. Whitish strips are also attested in the analyzed mummy sample. They were primarily employed to highlight specific somatic features, such as teeth or iris, and to enhance chromatic contrast in patterns where white, light, and dark brown strips were combined (e.g., MM_11296). This coloration was possibly achieved through a bleaching process, a technique employed in ancient Egypt for a range of purposes [22].

Naturally colored and dyed strips, as well as the textile pieces positioned along the sides and bottom of the bundle to frame the pattern and secure the layout, are fixed both to one another and to the underlying textile layer using small dots of adhesive substances. Experimental reconstructions conducted as part of the present study proved that a minimal amount of adhesive, applied in strategic points, was sufficient to firmly hold the layout in place. This confirms Whittemore’s [23] account of the wrappings of ibis mummies discovered at Abydos, in which he notes: “The wrapping was then continued with short bits and longer bands, similarly lashed down with thread, with here and there the slightest trace of gum”. These adhesive dots are typically located at the ends of the strips, securing them to the ground fabric (see below), as well as at the binding points, and along the edges of the side textile pieces. Two types of adhesive, one dark-colored and the other reddish, have been observed, suggesting the use of different binding agents. While the use of hydrolyzed plant sugar gum has been suggested, the limited number of studies conducted on the subject prevents any definitive conclusions at this stage [24]. Seams securing the edges of strips or flat fabrics have been observed in only two specimens, and even there, they were combined with adhesive substances (MM_11293, PMEA_LDUCE-UC6985).

These adhesive matters preserved the tight interlacing and overlapping of the strips, making it impossible to determine their actual dimensions. Measurements were taken only from a limited number of particularly deteriorated specimens, in which the decorative patterns had lost their original weave and the strips had become loose and readily accessible. In these cases, the strips were found to have an average height of approximately 1.8 cm, ranging from 4.5 to 0.5 cm. A further difficulty in assessing their size arises from the common practice of folding the torn and frayed edges of the strips, toward the non-visible side, in order to create cleaner and more refined edges. The resulting creases appear sharp and regular. Given the precision and consistency of these folds, one may wonder whether a tool was employed in their creation. Strips could be folded in half or along one or both edges of the strips, depending on their intended position within the decorative pattern and the construction technique used to produce it.

The image-based modeling protocol developed for this study offers unprecedented access to the decorative wrapping patterns across the entire surface of the bundle. By setting different color modes on the resulting high-resolution 3D models and virtually unwrapping their textured mesh, it was possible to document with an unparalleled level of detail and precision the exact arrangement of the interlaced and overlapped narrow linen strips, thus gaining a deeper understanding of the original wrapping weave structures as conceived by the craftsmen (Figure 10). Once this data had been thoroughly captured in digital form, accurate line drawings of the decorative patterns were produced directly on the 3D models, preserving thorough and reliable information on the structure and execution of the wrappings at true scale. The resulting digitally vectorized 3D models served as precise geometric references for mapping and analyzing the decorative layouts, carrying out morphometric analyses that highlighted formal and structural similarities, thereby allowing for the grouping of mummies into morphological and stylistic clusters, and ultimately facilitating the understanding of the construction logic behind these complex designs.

Figure 10.

Split visualization showing geometry and texture of hawk mummy MM_TN 4295 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester).

3.2.1. Pattern Construction Techniques

The technical methods used to construct the decorative patterns on the outermost surface of votive animal mummies have been compared to weaving and basketry techniques [11]. However, the detailed morphological analysis of pattern geometries, coupled with experimental archaeological practice carried out during this study, has made it possible to outline the mechanical movements involved in their execution. This clearly shows that, although comparable in appearance, the techniques underlying the construction of wrapping patterns can differ significantly from those used in traditional weaving and basketry. Furthermore, accurately documenting the movement dynamics and technical differences in execution has enabled a deeper understanding of the construction logic and led to the identification of two main techniques through which a wide variety of decorative patterns could be created: interlacing and winding.

Given that in all patterns the strips may be overlapped, interlaced, and at least partially wound around the bundle at the same time, the fundamental technical distinctions between these two techniques lie in the location of the strips’ starting points, their directional logic, and the extent to which the decorative design covers the surface of the bundle. In interlacing techniques, the strips are overlapped and interlaced while being wound only partially around the bundle. This results in a pattern restricted to a specific side of the bundle, typically the back (as seen in some crocodile or fish mummies) or the front (as in certain cat or dog mummies), and requires additional textile pieces to conceal the undecorated areas. Conversely, in winding techniques, the interlaced and overlapped strips are wound completely around the bundle, distributing the decorative pattern more or less uniformly across its outer surface. This structural difference implies a different path for the strips and, as a result, a distinct set of movements and gestures performed by the craftsperson.

The interlacing technique involves the crossing of vertical and horizontal strips in a regular and orderly manner to create repeated decorative patterns. The starting points are fixed and consistent: the vertical strips were typically secured at the top of the bundle, or at the neck when a modeled head was present (Figure 11), while the horizontal strips were generally fixed to one of the sides of the bundle using small amounts of adhesive. This anchoring system ensured that the strips remained under tension, much like threads on a loom, an essential condition for the stability and integrity of the decorative design. Insights from recent experimental archaeology confirm that when performing the interlacing method, it would have been extremely difficult to maintain the strips in place without anchoring points on the ground fabric, especially when producing patterns with significant depth, even if large amounts of adhesive were applied at the binding points, which, as noted, was not the case in votive animal mummies. These observations strongly rule out the possibility that patterns produced with this technique were created off the mummy and later applied to it. Rather, it is far more reasonable to assume that the decorative module was constructed directly on the surface of the bundle. The logic underlying this technique is generally unidirectional, from top to bottom and from one side to the other. This arrangement resulted in one or more parallel columns of repeated motifs, usually confined to the front or back surface of the bundle. The undecorated sides of the mummy were then covered with additional textile pieces, applied to complete the design, refine its edges, and conceal the exposed background layer.

Figure 11.

Starting points of vertical strips fixed with dots of adhesive at the neck of the dog mummy MET_13.182.49 (photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art).

The winding technique entails the use of a single continuous strip, multiple sets of strips, groups of threads, or even a flat piece of textile that may follow different directional logics and originate from various starting points, depending on the anatomical features and dimensions of the specimen, as well as the intended design. In some examples, the winding began at the bottom, with the strips ascending diagonally around the bundle, passing over the top, and terminating on the opposite underside (i.e., from bottom to top and back down). In such cases, small button-shaped elements made of hardened textile were introduced at the convergence points of the strips at both the top and bottom of the bundle. These elements served not only to anchor and neatly terminate the decorative scheme, but also to conceal structural transitions and enhance the overall visual coherence of the pattern (Figure 12). In other instances, the strips were wound around the bundle in the opposite direction (from top to bottom and back up): starting from the top or neck, they continued diagonally downward along the body, passed over the bottom, and terminated on the opposite side from their point of origin (e.g., WM_56.22.152). In these examples, the starting points of the strips were concealed beneath one or more strips wound around the neck, while the bottom formed an integral part of the decorative layout. The pattern applied to this area could even differ from that of the main body, as observed in specimen OSA_903, where a bi-colored herringbone-filled lozenge pattern on the main body transitions into a concentric square pattern at the bottom (see below). Alternatively, the strips could be applied front-to-back or back-to-front, enveloping the bundle along its horizontal axis (e.g., MM_11293). In some of these cases, the layout was refined by covering the bottom with a separate textile piece (e.g., ME_C.2349/4).

Figure 12.

Button-shaped elements of hardened textile at the top and bottom of the ibis mummies (a) NMD_7464 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of National Museum of Denmark) and (b) WM_1969.112.42 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum).

A dynamic and flexible application of these techniques was observed, reflecting both functional considerations, such as stabilizing the shape of the bundle, and aesthetic intentions aimed at achieving specific visual effects on the outer surface. Notably, no single pattern can be rigidly attributed to one specific manufacturing technique, as the same decorative design could often be produced using either method or a combination of both (Figure 13). This reflects the craftsmen’s remarkable manual skill, technical awareness, and a deep knowledge of wrapping procedures, as well as a capacity to adapt or reinterpret decorative schemes, occasionally in entirely original ways, to accommodate specific functional, aesthetic, or ritual requirements.

Figure 13.

Cat mummy REM_RC-1676 produced using a combination of interlacing and winding techniques (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, California, USA).

3.2.2. Pattern Morphologies

Patterns are configurations resulting from the complex interplay of material, technical, and decorative choices. They embody a specific visual language that conveys aesthetic values, divine associations, and the ritual mechanics of sacred transformation.

Different geometric layouts, resulting from variations in visual rhythm, technical composition, and color contrast, have been identified. These can be broadly categorized into three levels of complexity: highly, moderately, and minimally elaborated. Within these macro-categories, patterns are classified into classes and subclasses, according to their primary technical and aesthetic features. This framework is supported by a specifically developed terminology, which is precise, accessible, and semantically flexible, to capture the richness and diversity of the decorative schemes.

The seven main classes (❖) refer to the overarching structural composition of the pattern. Each comprises a variable number of subclasses (■), which reflect structural variants that change the visual effect and enrich the main layout. These variations involve different strip arrangements and the application of one or more techniques described above. Color variants (●) within the subclasses manifest through the alternation of colored, natural, and possibly bleached strips, which further enhance the complexity and visual richness of the decorative scheme.

Highly Elaborated Patterns

Highly elaborated patterns are defined by the use of repeated modular, three-dimensional geometric designs and the extensive application of linen strips with contrasting colors and textures. These features underscore a high degree of technical abilities and visual sophistication, particularly evident in square, lozenge, and weave patterns.

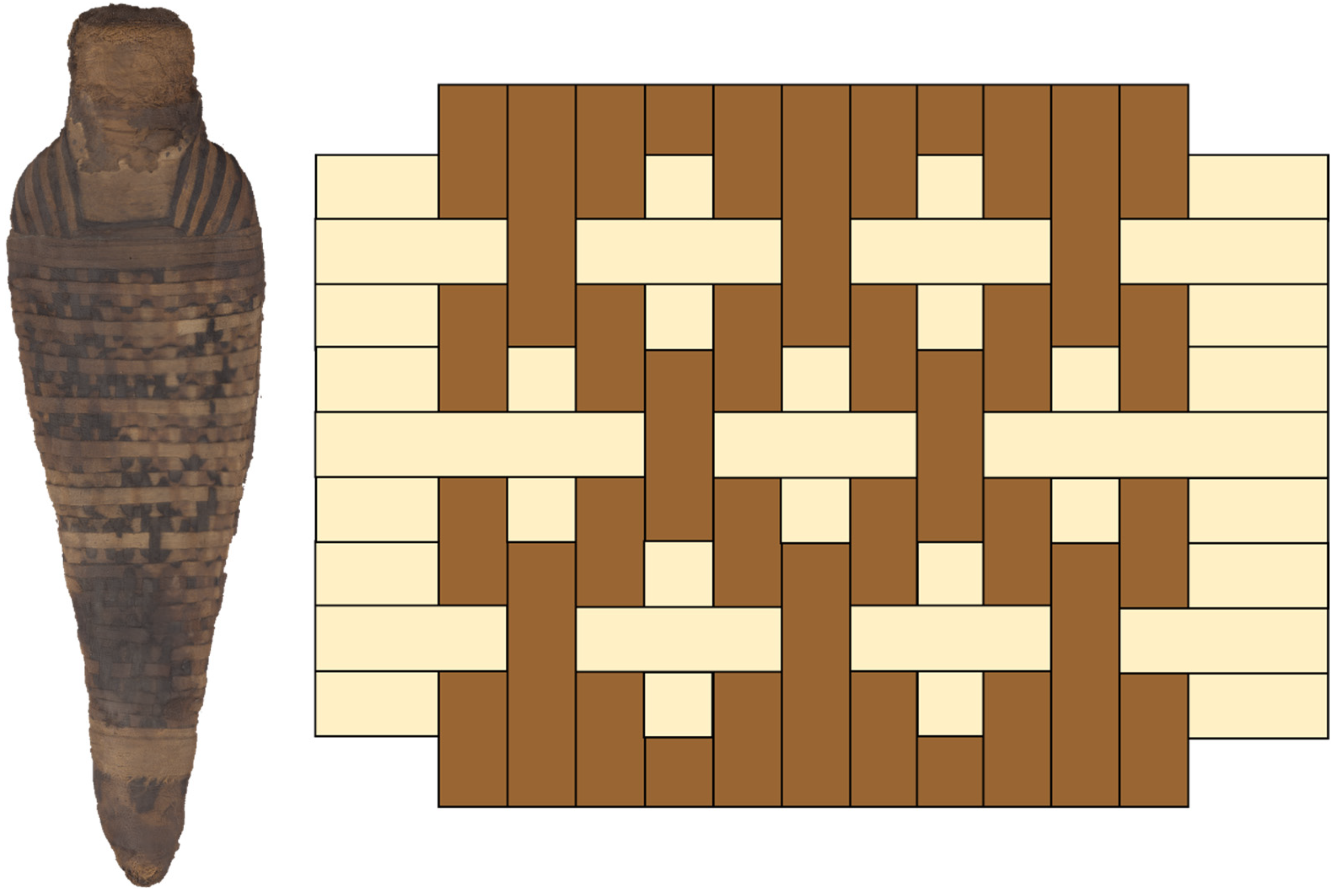

❖ Square pattern

The square pattern refers to modular geometric layouts based on the repetition of square or rectangular units, depending on the dimensions and the shape of the bundle (Figure 14). These modules are created using vertical and horizontal strips, folded along their edges to produce clean outlines. However, some particular specimens feature framing strips folded along only one edge. The frayed and unfinished sides are concealed at the center by an additional contrasting strip, neatly folded along both edges (e.g., MFAB_ Eg.Inv.6255). The end of each vertical and horizontal strip is secured at the top or neck, when a modeled head was present, and along the sides of the bundle, respectively, using dots of adhesive. Once fixed to the ground fabric, the strips are interlaced to define the overarching structural composition, which constitutes the most visually prominent component of the pattern.

Figure 14.

Examples of a square pattern based on the repetition of square units on (a) the ibis mummy REM_RC-226 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, California, USA) and rectangular units on (b) the crocodile mummy CMNH_1867-4 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History).

Square patterns are most commonly produced using the interlacing technique. However, in more intricate examples, they may also be produced through the winding technique, or by combining both methods. Depending on the execution, the layout may range from square modules, arranged in one or more parallel rows aligned with the longitudinal axis of the mummy’s body (corresponding either to the back, as in MHM_MM 19232, or to the front side of the bundle, as in ME_C.2349/6), to a dense, continuous, and highly structured grid that can cover the entire bundle (Figure 13).

The scale and spacing of each square, which strongly affect the symmetry and final visual effect, were likely achieved through the use of precise tools and/or techniques. This hypothesis is supported by both experimental reconstructions and morphometric analyses, which have revealed sub-millimetric variations in square dimensions and placement. Such precision suggests not only highly refined manual skills, honed through repeated practice, but also the probable use of measuring tools or a grid system, akin to those employed in Egyptian painting and sculpture to ensure consistent proportions and standard registers. This deliberate pursuit of geometric accuracy points to a clear intention toward modular logic, formal balance, and surface planning, reflecting advanced technical expertise in the design and execution of the wrapping. This is further demonstrated by the presence of diverse configurations within the square units, which for a long time have been inconsistently referred to, sometimes as coffer, meander, or herringbone pattern, while other variants have remained entirely unnamed, contributing to a misleading understanding of these decorative schemes. These design variants gave rise to multiple structural subclasses, each encompassing distinct chromatic variants. Color contrast was achieved by alternating strips in various shades of natural flax with those dyed in light or dark brown, black, or reddish hues (bright red, pink, and orange). In only one specimen, the strips are impregnated with a green resin-like substance (PMEA_ LDUCE-UC45978). Such combinations significantly contribute to the overall visual rhythm, complexity, and aesthetic appeal of the bundle.

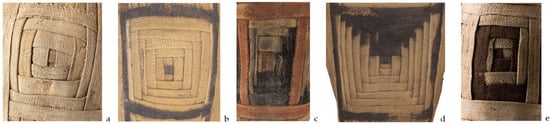

■ The concentric square pattern is characterized by a series of nested square or rectangular units, each consisting of multiple layers of strips arranged to form progressively larger concentric squares or rectangles. This arrangement creates a stepped and raised appearance, emphasizing both surface articulation and volume, as the recessed strips generate a pronounced texture contrast.

The pattern is constructed by first placing a central vertical strip, often flat, as in MFAB_ Eg.Inv.6255, though examples like ME_P.6110 show it may also be folded along one side. In rare cases, the central strip may be replaced by a cross-shaped motif, achieved through the crossing of a vertical and a horizontal strip, each with its edges folded inward (e.g., PENN_E12443). In the most common cases, after securing the central strip, a desired number of vertical strips are subsequently fixed with dots of adhesive on either side of its upper end, alongside horizontal strips secured along one side of the bundle. The anchoring points are usually concealed with further flat fabrics that also cover the unpatterned surfaces of the bundle, such as the back, bottom, top, and, in some cases, the sides. Each strip is typically folded only along its visible edge, while the opposite side remains flat. This configuration allows the subsequent strip to rest neatly on top, improving adherence and preventing bulk or slippage. The folded edge of the new strip serves to conceal the frayed edge of the previous one, resulting in a cleaner and more refined finish. The number of these strips may vary considerably. It has been suggested that, in this pattern, the number of vertical strips always equals the number of horizontal ones [11]. However, although symmetry is common, several examples demonstrate that the numbers do not always correspond (e.g., REM_RC-226, Figure 14a).

The pattern is constructed by gradually moving from the vertical strips closest to the central one outward. The same logic applies to the horizontal strips: the innermost ones are placed first, followed by the outermost. Accordingly, after the arrangement of the first central strip, the two vertical ones are laid along its length, followed by a pair of horizontal strips (e.g., WM_42.18.2). This sequence is then repeated to complete the composition. Conversely, two horizontal strips may first be placed over the central vertical one, followed by a pair of vertical strips (e.g., MFAB_Eg.Inv.6200.1).

The use of differently colored strips enables a range of chromatic variations, which may also produce significantly different visual outcomes within the concentric square pattern:

- Single-colored is characterized by a monochromatic scheme, created by using undyed strips. The decorative effect relies entirely on their geometric arrangement which, despite the absence of chromatic contrast, achieves a subtle degree of complexity (Figure 15a);

Figure 15. Details of different chromatic layouts in the concentric square pattern: (a) single-colored on the snake mummy ME_P.6110 (photo: Museo Egizio); (b) bi-colored on the ibis mummy YPM_ANT 006924.002 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of the Anthropology Division at the Yale Peabody Museum); (c) half-colored on the crocodile mummy PAHMA_6-21633 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, © 2024 Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California); (d) quarter-colored on the ibis mummy BKM_X1179.4 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Brooklyn Museum); (e) meandered on the cat mummy ME_C.2349/7 (photo: Museo Egizio).

Figure 15. Details of different chromatic layouts in the concentric square pattern: (a) single-colored on the snake mummy ME_P.6110 (photo: Museo Egizio); (b) bi-colored on the ibis mummy YPM_ANT 006924.002 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of the Anthropology Division at the Yale Peabody Museum); (c) half-colored on the crocodile mummy PAHMA_6-21633 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, © 2024 Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California); (d) quarter-colored on the ibis mummy BKM_X1179.4 (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of Brooklyn Museum); (e) meandered on the cat mummy ME_C.2349/7 (photo: Museo Egizio). - Bi-colored is featured by the use of strips in contrasting shades, typically light and dark. The color contrast may be evenly distributed within each unit, alternating along the entire perimeter to create the effect of concentric squares in alternating light and dark hues (e.g., BM_EA35712), or it may be concentrated on specific sections, such as the central core and the outer frame, thus producing a chromatic contrast between innermost and outermost squares (Figure 15b). Compared to other two-colored variants, where chromatic contrast may emphasize a specific direction (see below), this variant achieves a more uniformly modulated visual rhythm within each square and a balanced distribution of color;

- Half-colored retains the geometric precision typical of concentric square patterns but introduces greater visual complexity through chromatic segmentation. Each unit is composed of linen strips in two contrasting colors, usually light and dark. The dark vertical strips are only those placed on one side of the central strip, while the dark horizontal ones are positioned either above or below the square’s center. This creates the visual effect of squares diagonally split into two contrasting colored sections along the diagonal axis. The result is a dynamic, asymmetrical visual rhythm. The arrangement of the colored halves within each square may be either consistent or alternating across the surface of the mummy. In some examples, the diagonal division is repeated with the same orientation in every square, creating a stable and orderly visual effect (e.g., MDN_56.2865 (223)). In others, the orientation of the diagonal alternates from one square to the next, generating a more dynamic and visually varied rhythm. For instance, in SAMA_2005.1.37, the orientation of the colored diagonal split alternates along the vertical axis of the mummy, producing a zigzag effect. As a result, each square appears to rotate in relation to the next, disrupting the linear regularity of the wrapping motif and introducing a sense of movement and visual variation. By contrast, in MHM_MME 1978_001, the diagonally divided squares maintain a consistent orientation within each vertical row. The square units are arranged in two parallel columns along the bundle’s body, with the color split running in the same direction throughout the sequence. This results in a more stable and symmetrical appearance, reinforcing a sense of structured order and bilateral organization. In some specimens, this chromatic contrast is further enhanced by the use of framing strips in bright hues, adding an additional level of visual articulation (Figure 15c);

- Quarter-colored introduces a subtler chromatic segmentation compared to the half-colored variant. The colored quarters are produced using darker linen strips that contrast with the naturally colored ones, or with strips dyed in vivid hues such as red (Figure 9). The arrangement of these quarters can follow different logics: when the contrasting color is applied to only one quarter of each concentric square, its position is determined by the placement of the dark strips. If the dark quarter is located in the upper section of the square, this means that only the horizontal strips positioned above the square’s center are dyed dark brown or black (Figure 15d). When the dark quarter occupies the lower section of the square, only the horizontal strips below its center are dark (e.g., MFAB_72.4913). If the dark quarter is placed on the right side of the central strip, then only the vertical strips to its right are dark colored (e.g., BKM_37.1984E). Conversely, when it is positioned on the left, only the vertical strips to the left of the central strip are dark (e.g., CMNH_4918-2). In some specimens, two dark quarters are present and can be arranged on opposing sides of the square to create a mirror-like configuration (e.g., ME_C.2349/5) or aligned along the vertical axis in upper and lower positions, forming an hourglass configuration (e.g., CMNH_1867-4). These arrangements produce more subtle and directional visual effects. While in some cases, the positioning of the colored sections remains consistent across the entire surface of the mummy, creating a harmonious and symmetrical rhythm, in others the careful arrangement of quarter contrast allows for a rich variety of compositional solutions and dynamic surface effects. For instance, in ME_C.2349/8 and BKM_X1179.1, the dark quarter appears in the lower part of one square and the upper part of the next, generating a diamond-like visual progression along the axis of the bundle. A combination of hourglass and diamond-like configurations is present in MET_13.186.9, where horizontal dark strips are arranged in both the upper and lower sections of each square. When the square units are arranged in rows, the placement of dark-colored quarters may remain consistent across the entire surface of the mummy, by emphasizing visual order and repetition (e.g., MFAB_72.4914). In other cases, the distribution is more elaborate, with the position of the dark quarters varying from one square to the next, thereby enhancing the complexity of the final visual effect (e.g., PENN_E12441);

- Meandered has long been considered a distinct decorative pattern. However, a thorough examination, supported by experimental reconstruction, has shown that this is a variant of the concentric square pattern, as the arrangement of vertical and horizontal strips follows the same structural logic. However, the dark strips are not arranged to create the effect of concentric squares in alternating light and dark hues, nor are they placed on specific sections of the square as in the bi-colored variant, or on one or more sides of a unit to produce chromatic segmentation as in the half-colored and quarter-colored variants. Instead, they are laid alternately in horizontal and vertical positions in such a way as to generate an optical illusion of a continuous, labyrinthine path that gives rise to the characteristic meander-like appearance. Depending on the specific layout of the strips, this meander effect can unfold in either a clockwise (e.g., Louvre_N 2678 D) or anticlockwise direction (e.g., ME_S.11030). In either case, it may begin from the upper edge (e.g., ME_C.2349/2), the lower edge (Figure 15e), or from the longer sides of the square (e.g., ME_S.11030).

Some chromatic variants of the concentric square pattern can also be combined within a single module. For instance, one half of the square may be dark-colored, while the opposite half is divided into two contrasting quarters, each in a different hue (as seen in a crocodile mummy kept at the Sharm El-Sheikh Museum of Antiquities). Alternatively, diverse chromatic variants can be applied to different units across the same mummy: some cases display squares arranged in vertical succession, one presenting a quarter-colored variant, the next a half-colored one (e.g., ME_P.1464), while other specimens show alternating units combining quarter-colored variant and bi-colored layout (e.g., MM_13861). In other examples, entire rows may be composed of quarter-colored squares adjacent to rows with single-colored units (e.g., ME_C.2350/5), whereas in other mummies, rows in quarter-colored variants alternate with rows in half-colored ones (e.g., Louvre_N 2678 C).

■ The herringbone-filled square pattern retains the geometric modularity of the square design, which frames strips forming a distinctive herringbone weave. The herringbone infill may be aligned to the left or right side of each unit, depending on the intended visual effect, thereby allowing for subtle variations in compositional balance. The design is achieved by anchoring a desired number of vertical strips with adhesive to the top or neck of the bundle, while an equal number of horizontal strips are secured along one side. Both the vertical and horizontal strips are folded only along their visible edge, while the opposite side is left flat and frayed to allow for smoother application of the subsequent strip. Unlike the concentric square pattern, this design is not built around a central strip but rather begins with the first applied vertical strip laid along the longitudinal axis of the bundle, followed by the innermost horizontal strip aligned perpendicularly to the vertical one. This sequence is then repeated to complete the composition, thereby producing a stepped appearance. The use of alternating light and dark linen strips further accentuates the visual rhythm of this variant (Figure 16), which introduces movement and fluidity within the square structural composition.

Figure 16.

Dog mummy MFAB_72.4916 showing a herringbone-filled square pattern (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

■ The diagonal cross-filled square pattern is characterized by the use of diagonal strips that intersect to form a diagonal cross within each square unit. This infill enriches the logic of the traditional square design with a directional tension that animates the interior of each module.

The strips, which are as long as the diagonal of each square, are folded only along their visible edge to create a cleaner visual finish and to allow easier application of the next strip over the flat side. The design is often composed of overlapping light and dark linen strips over a light background, thereby enhancing the readability of the infill design (Figure 17). While the overall layout preserves modular and structural order, the introduction of the diagonal cross adds a dynamic element that enlivens the square pattern and establishes a rhythmic sequence across the surface of the bundle.

Figure 17.

Crocodile mummy MM_12008 decorated with a diagonal cross-filled square pattern with two strips crossing at the center (3D model: C. Rindi Nuzzolo, courtesy of Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester).

❖

Lozenge pattern

The primary visual units in the lozenge pattern are closed rhombus-shaped modules, resembling squares rotated 45 degrees, typically referred to as diamonds. However, while this term is broadly descriptive, it lacks the technical and decorative specificity of lozenge, which is the more precise definition for this layout.

The lozenge pattern is formed by strips usually folded along both edges to produce a clean and controlled finish. Nevertheless, special cases are attested: for example, WM_56.22.152 shows strips folded along only one edge, leaving the opposite side visibly frayed, while WM_1969.112.42 features strips also folded along a single edge, with the unfinished margins concealed by groups of threads. Once folded, the strips can be interlaced, wound around the mummy, or arranged through a combination of both techniques. Depending on the chosen method, they may be secured at one end of the bundle (such as the top), then run diagonally along one side of the body, pass beneath the bottom, and rise back up along the opposite side. This creates a sequence of repeated lozenges covering the entire surface of the bundle (e.g., Louvre_E 2810). Alternatively, the lozenges may occupy only a single section of the mummy, namely the main viewing surface, which can correspond either to the front (e.g., BM_EA6754) or to the back (e.g., Louvre_N 2901 ter). In such cases, the strips run diagonally along one side of the bundle, from the upper section to the lower edge. The remaining unpatterned areas are covered with extra pieces of flat fabric (e.g., MM_TN 4295).

According to the technique used, the shape and size of the bundle, and the desired visual outcome, the modules may be slimmer, elongated lozenges with sharply acute angles (e.g., PENN_E568), broader and flatter units with a more horizontal emphasis (e.g., ME_P.1460/13), or highly symmetrical forms with balanced proportions (e.g., BM_EA6752). Within these lozenges, different inner geometric configurations could be created, resulting in various subclasses, each potentially executed with color-contrasting strips ranging from natural flax shades and bleached linen to light or dark brown, black, or even brighter hues such as red or reddish-brown.

■ The concentric lozenge pattern is composed of multiple layers of linen strips arranged progressively from the innermost to the outermost, to create a nested visual effect. This imparts a highly sculptural and refined appearance, further enhanced by the directional flow along a continuous diagonal layout. As in the square pattern, the design is typically built around a central strip, usually unfolded. However, in some cases, it may be replaced by two narrow strips, folded along both edges and diagonally crossed at the center of the module (Figure 18). After securing one end of the central strip to the midpoint of one side of the lozenge, a desired number of additional strips are applied parallel to it and anchored to the right and left of its end. At the same time, further strips are secured to the adjacent side of the lozenge. In this way, two groups of strips are created, secured, respectively, to two adjacent sides of the lozenge. The anchoring points, usually located on the top and sides of the bundle, are later concealed with pieces of flat fabric or, when placed near the neck, covered with one or more strips wrapped spirally around it. Each strip used for the infill of the lozenge units shows the visible edge folded inward, while the opposite side remains flat. This solution provides a stable surface for the subsequent strip while concealing the frayed edge beneath, ensuring a cleaner finish. Once all the strips have been secured at one end, the construction proceeds gradually from the innermost to the outermost strips. Unlike the square pattern, where the strips are laid in pairs, in the concentric lozenge pattern the strips are interlaced individually, resulting in a slightly more complex arrangement: a first strip is placed parallel along one side of the central strip (for example, the right), followed by a second strip, belonging to the second group of strips, anchored on the adjacent side of the lozenge; then, a third strip, belonging to the first group, is applied parallel to the first one on the opposite side (for example, the left), and finally, a fourth strip, from the second group, is laid parallel to the second strip. This process is repeated systematically to complete the composition, creating a complex yet strikingly orderly structure. The use of contrasting colored strips further enriches the design, generating remarkable differences in the final appearance and giving rise to a wide range of chromatic variants:

Figure 18.

Detail of the ibis mummy WM_1969.112.42 showing a concentric lozenge pattern (3D model: C. Rindi Nuzzolo, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum).

- Single-colored is made by strips in the natural hue of flax fiber. The nested motif is further accentuated by the monochrome palette, which focus the attention on the geometric articulation of the surface (e.g., CMNH_1764-4b);

- Bi-colored is constructed by alternating light and dark strips distributed uniformly along the entire perimeter of each lozenge. As a result, the visual effect reveals a clear alternation of nested rhombuses in contrasting hues, enhancing depth and geometric articulation within each unit. In contrast to other chromatic variants (see below), where color segmentation may appear directional, here the uniform distribution of the bicolor scheme creates a balanced composition (Figure 19);

- Half-colored displays the bicolored contrast limited to specific sections of the geometric rhombus-shaped modules. As in other variants, light-colored strips, either naturally colored or bleached, are interlaced with dark-colored strips, ranging from light to deep brown. In this configuration, the darker strips correspond to half of the strips in both the first and second group. This arrangement produces the visual effect of lozenges diagonally split into two contrasting colored sections, aligned either along their major axis (upper–lower contrast) or minor axis (left–right contrast). The distribution of the colored sections within each lozenge may remain uniform over the entire surface of the mummy, producing a stable, symmetrical composition (e.g., MHM_MM 18400). In other cases, the orientation can alternate from one lozenge to the next, creating a dynamic variation. In these instances, the orientation of the diagonal contrast reverses systematically, so that each lozenge appears rotated by 180 degrees relative to another one. This alternation creates a dynamic sequence that imparts a rhythmic motion (BM_EA6754);

- Quarter-colored is characterized by a chromatic contrast that creates a subtle asymmetry within each unit. The color emphasis is confined to one or two quarters of the lozenge, resulting in a more fine and directional visual effect. The colored quarters are made with dark strips, typically dyed brown or black, alternating with light strips. Depending on the placement of the dark strips, the position of the dark quarter within each lozenge also changes. Some specimens display only a single-colored quarter (e.g., Louvre_N 3656). In other examples, the dark strips are arranged to create two opposing dark quarters, establishing a directional logic with two dark and two light quarters facing each other in a mirror-like configuration (e.g., CMNH_4918-3). In more distinctive cases, the two opposing quarters are in different colors. In the mummy BM_EA6752, for instance, two facing quarters are naturally colored, while the other two are light and dark brown, respectively, producing a more sophisticated design.

Figure 19.

Cat mummy WM_56.22.152 patterned with a bi-colored concentric lozenge scheme (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum).

Figure 19.

Cat mummy WM_56.22.152 patterned with a bi-colored concentric lozenge scheme (3D model: M. D. Pubblico, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum).

These different chromatic variants can also appear within the same concentric lozenge unit. For instance, one half of a lozenge may be dark-colored, while the opposite half displays two quarters in contrasting shades (e.g., BM_EA6752). Other mummies may feature lozenges with diverse chromatic variants: in certain instances, quarter-colored lozenges alternate with half-colored ones (e.g., MM_6098), whereas other specimens exhibit sequences where half-colored lozenges are interspersed with entirely monochrome modules (e.g., BM_EA6754).

■ The herringbone-filled lozenge pattern consists of lozenge units that frame a herringbone infill. The linen strips used to create the herringbone infill have the visible edge folded inward, while the opposite side is left frayed to allow for secure anchoring of the following strip, preventing it from slipping. This arrangement also ensures a cleaner finish, as each strip covers the unfolded edge of the previous one. The strips can be anchored either to the bundle’s bottom (BM_EA68219) or at the top/neck (Louvre_E 2810). The decorative motif may be positioned only on the visible surface of the mummy, with the remaining sides covered by additional pieces of flat fabric (e.g., Louvre_N 2901 ter), or it may be distributed evenly over the entire surface (Figure 20). Within each unit the strips seem to run obliquely from the two adjacent sides of the lozenge towards the opposite ones. The herringbone infill is obtained by crossing two symmetrical strips so that they meet diagonally along the major axis of the lozenge. The crossings progress in sequence, starting from the strips closest the upper vertex and moving toward those positioned further down. In this way, a stepped appearance is created, similar to that of the herringbone-filled square pattern but rotated approximately 45 degrees. The use of contrasting-colored strips gives rise to subtle variations of the motif that emphasize its directional flow:

- Single-colored displays a restrained, monochromatic palette dominated by natural flax hues. However, the strips can exhibit subtle variations in the natural flax shades, ranging from pale beige to light brown, creating a delicate contrast that accentuates the geometric herringbone-filled lozenge pattern (e.g., Louvre_E 2810);