1. Introduction

The Niokolo-Koba National Park (NKNP) was established in 1954 in the southeastern part of Senegal, within the Sudano-Guinean zone [

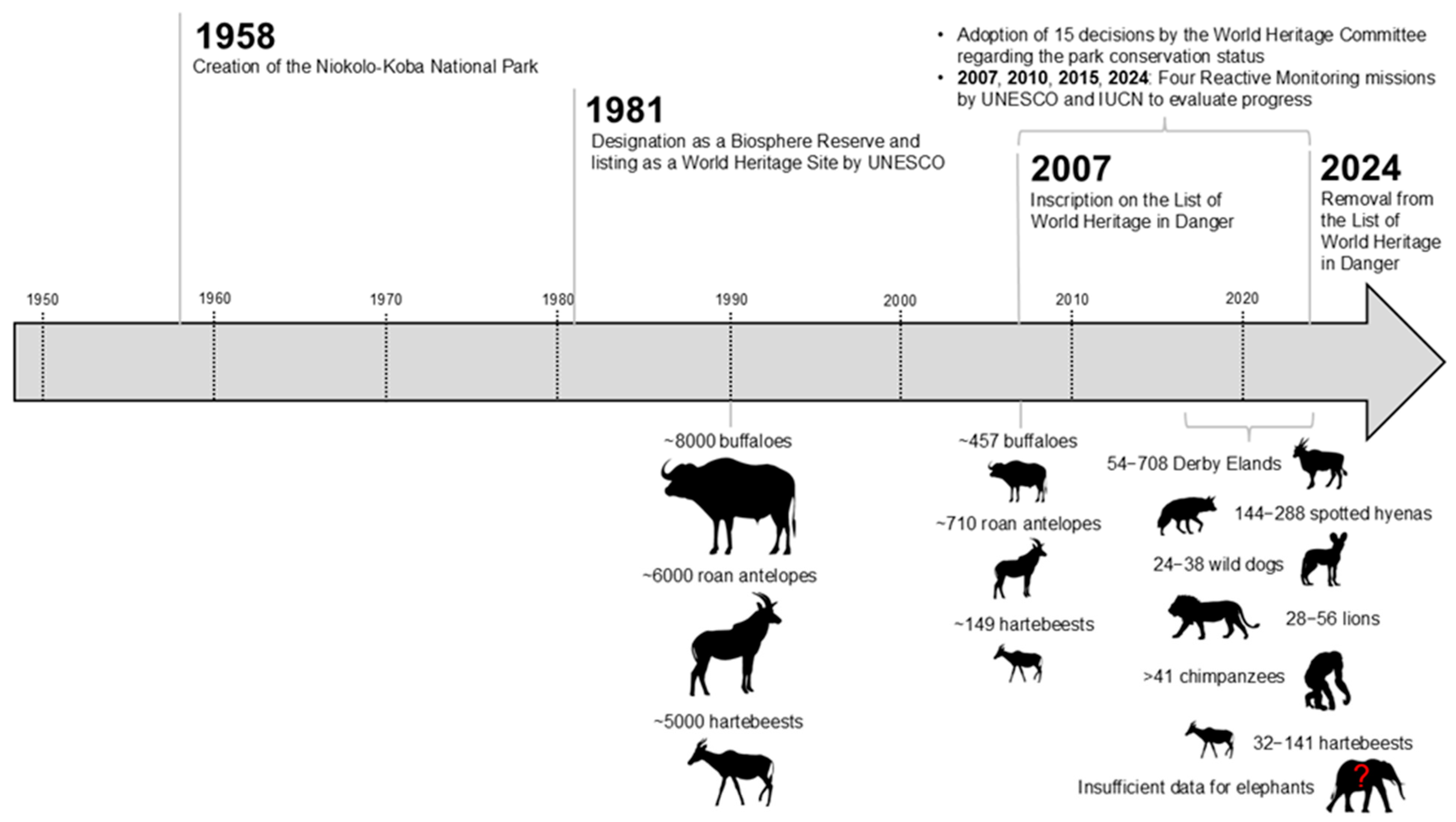

1]. In 1981, UNESCO designated it as a Biosphere Reserve and listed it as a World Heritage Site for its exceptional biodiversity (criterion (x)). In 2007, the site was inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger during the 31st session of the World Heritage Committee in Christchurch due to the severe impact of poaching on mammal populations, livestock grazing, and the potential effects of the planned construction of the Sambangalou dam on the Gambia river upstream of the park

1. During its time on the List in Danger, the World Heritage Committee adopted 15 decisions regarding its conservation status. Additionally, UNESCO and IUCN conducted four Reactive Monitoring missions in 2007, 2010, 2015, and 2024

2 to evaluate progress in implementing corrective measures and achieving the indicators of the Desired State of Conservation for its Removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger (DSOCR). In 2024, the World Heritage Committee acknowledged the efforts made by the State Party of Senegal to improve the site’s conservation status. As a result, the Committee decided to remove it from the List in Danger, making it the seventh national park

3 in sub-Saharan Africa to be definitively removed from that list after Ngorongoro Conservation Area (United Republic of Tanzania) in 1989, Rwenzori Mountains National Park (Uganda) in 2004, Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary (Senegal) in 2006, Comoé National Park (Côte d’Ivoire) and Simien National Park (Ethiopia) in 2017, and Salonga National Park (Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 2021. It was the only site removed from the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2024.

The NKNP remained in danger for 17 years due to severe human interference, such as poaching and illegal development, as well as governance challenges. These issues were particularly prevalent in ecologically fragile and socio-economically pressured regions. However, the country made efforts to preserve the site’s Outstanding Universal Value over the years. In this context, it is important to document the entire process of including the NKNP on, and removing it from, the World Heritage List in Danger, as this reveals complex internal and external challenges and governance needs in heritage conservation. Moreover, many sites in Africa continue to be listed as World Heritage Sites in Danger due to threats that exceed the control of park management teams, such as armed conflict. In this context, the NKNP has emerged as a noteworthy example, as it remains directly unaffected by such insecurity [

2]. Globally, the List of World Heritage in Danger has received limited academic focus [

3]. As of 2025, sub-Saharan Africa remains the region with the highest number of natural sites on this list, accounting for 9 out of 14 natural sites in danger by the end of the 47th session of the World Heritage Committee in July 2025 in Paris [

4].

We formulated two hypotheses: (i) the State Party of Senegal initially posed a threat to the integrity of the Niokolo-Koba National Park (NKNP), leading to its inscription on the List in danger; and (ii) improved national governance systems and strengthened partnerships subsequently contributed to preserving the Outstanding Universal Value of the NKNP, leading to the site’s removal from the List in danger. Based on a qualitative analysis of previous decisions made by the World Heritage Committee, reports from the joint UNESCO/IUCN Reactive Monitoring missions, and other relevant information available regarding the site, this study aims to document the process that led to the NKNP’s recent removal from the list in danger, identifying both the risk factors that contributed to such removal and the positive factors that contributed to its rehabilitation. Additionally, we seek to provide insights into strategies for achieving these same results with other protected areas.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of the Conservation Status of Niokolo-Koba National Park from Its Inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2007 to Its Removal in 2024

During its 30th session (Vilnius, 2006), the World Heritage Committee adopted Decision 30 COM 7B.1

4. In point 4 of the decision, the Committee requested that the State Party of Senegal invite a joint World Heritage Centre/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission to assess the state of conservation of the NKNP. This assessment should include evaluating the status of key wildlife populations, the reasons behind reported declines in their population sizes, and the potential impacts of the proposed Tambacounda-to-Kedougou road construction project. In fact, this road was upgraded in the mid-1990s, dividing the property and creating a barrier for wildlife while providing easy access for poachers. This mission was undertaken from 21 to 27 January 2007, and it was concluded that the biggest threat to the safeguarding of the NKNP was commercial poaching, leading to a significant loss of its large mammal fauna and a threefold increase in cattle grazing. According to the report [

5], all ungulate species have experienced significant recent declines. Elephants (

Loxodonta africana) were on the verge of extinction, with the buffalo (

Syncerus caffer, subsp.

brachyceros) population reduced to about 457 individuals from an estimated 8000 in 1990. The number of roan antelope (

Hippotragus equinus) had decreased to only 710 from 6000, and the hartebeest (

Alcelaphus buselaphus) population had fallen to 149 from 5000 in 1990 [

5]. One development project was identified as directly impacting the park’s integrity. The mid-1990s upgrade of the Tambacounda-to-Kedougou Road effectively split the park into two. The second road, proposed to connect the town of Medina Gounas in Senegal with Koundara in Guinea, was subject to a detailed Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), and a decision was made to develop this infrastructure away from the park boundary. Potential new threats include the construction of a new dam on the Gambia River and of a trans-national highway linking Senegal (Tambacounda) with Guinea (Koundara). Even though discussions have been ongoing since 2005 between the NGO African Parks Network and Senegal regarding a possible public–private partnership agreement to improve the management effectiveness of the NKNP

5, given the degradation and the magnitude of the ongoing threats, the mission concluded, in consultation with Senegal’s Department of National Parks, that the site should be included on the List of World Heritage in Danger.

According to UNESCO and IUCN [

9], several factors significantly influenced the situation in which the park found itself. Its proximity to international borders, combined with regional insecurity and the proliferation of automatic weapons during the 1980s and 1990s, led to intense poaching pressures at a time when funding for both the park and its staff had been severely reduced. Moreover, the high standards of site management that had been established upon the park’s inscription on the World Heritage List were not sustained by the country. Additionally, it is worth noting that the park had not yet successfully engaged local communities in its management, as these communities felt a sense of alienation due to their eviction during the park’s establishment.

Based on the conclusions of the Reactive Monitoring mission, the World Heritage Committee adopted Decision 31 COM 7B.1

6 in Christchurch and expressed deep concern about the declining mammal populations, management issues, and potential impacts of a proposed construction project on the Gambia River. The Committee requested that Senegal take immediate action within 12 months to address these urgent threats to the park’s Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). As a result, the Niokolo-Koba National Park was added to the List of World Heritage in Danger during the World Heritage Committee’s 31st session in 2007 in Christchurch. The NKNP then submitted annual reports on its conservation status to the World Heritage Committee.

During its 32nd Session in Quebec City in 2008 and its 33rd session in 2009 in Seville, the World Heritage Committee expressed regret in both Decisions

7, that Senegal could not implement the urgent corrective measures within the proposed 12-month timeframe. Furthermore, no information was provided on the status of wildlife populations or on progress in addressing the identified threats. In 2009, the World Heritage Committee requested Senegal to invite a joint World Heritage Centre/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission to review the state of conservation of the NKNP and to assess the implementation of the corrective measures and timeframe set in 2007. The 2010 joint World Heritage Centre/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission took place from 4 to 11 April 2010 [

10]. It concluded that despite significant efforts by the State Party to control the main threat (poaching) to the park, the lack of resources in the surveillance system dramatically reduced its effectiveness. Other conservation problems, such as cattle grazing and agricultural encroachment, persisted almost throughout the park and were crucial to the effectiveness of the anti-poaching strategy. Additionally, the drying up of ponds and their encumbrance by two invasive plants (

Mimosa pigra and

Mitragyna inermis) were imminent and crucial threats, affecting even the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) and the sustainability of the diversity of the flora and fauna of the NKNP. Regarding the hydroelectric dam project, the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and discussions with the Gambia River Basin Development Organisation show that there were still concerns about the negative impacts on the NKNP, particularly the reduction in gallery forest and the change in the hydrological regime linked to the impounding of the dam. Additionally, the mission expressed concern about the conservation status of the NKNP, suggesting that it should remain on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Furthermore, it was suggested that any further deterioration could warrant consideration for removing the NKNP from the World Heritage List. Seven corrective measures were proposed to be implemented by 2013, given the specific threats to the NKNP and considering the State Party’s expressed commitment to prioritize conserving the protected area. These measures included strengthening the park’s ecological monitoring and surveillance system, implementing a program to restore the ponds, improving road conditions, providing practical alternatives to cattle grazing, and enhancing the marking of the park’s boundaries. During its 34th session, the World Heritage Committee adopted (Decision 34 COM 7A.11

8) the proposed seven corrective measures and requested the State Party to promptly survey the property’s key wildlife species with technical support from the IUCN Species Survival Commission. This survey would be used as a basis for monitoring the recovery of species and ecological conditions. Additionally, a new Reactive Monitoring mission was requested as soon as the identification of key wildlife species on the property was available.

In March 2011, a rapid aerial survey undertaken by Senegal revealed a significant decline in the mammal population and considerable degradation of the property’s Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). The World Heritage Committee, in its Decision 35 COM 7A.12

9 taken in UNESCO, Paris, reiterated its request to undertake a census of key species of fauna with the technical support of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. In response, Senegal decided to initiate a three-year Emergency Plan with funding of XOF 3 billion (EUR 4,573,470) to support the conservation of the NKNP. The World Heritage Committee invited the State Party to submit a request for international financial assistance. It encouraged the international community to support the urgent implementation of the corrective measures. Furthermore, the aerial survey report showed a large basalt quarry (the Mansadala quarry) inside the NKNP. Senegal was asked to take the necessary steps to close the quarry and rehabilitate the site. The specific request to elaborate a study on the impacts of the proposed dam at Sambangalou was still valid. The World Heritage Committee expressed the same concerns in 2012, 2013, and 2014. However, in its Decision 36 COM 7A.12 adopted in Saint Petersburg, it expressed satisfaction with Senegal’s decision to close the Mansadala basalt quarry.

Senegal requested international assistance from UNESCO to conduct a census of the large and medium-sized fauna in the NKNP, which was approved in March 2015. The census took place in April 2015 [

11], and a Reactive Monitoring mission, as suggested by the World Heritage Committee in 2010, visited the NKNP in May 2015. The mission concluded that Senegal had made commendable efforts to implement corrective measures, such as increasing surveillance staff and combating the encroachment of ponds. However, the available ecological monitoring data made it challenging to analyze the situation of the park’s threatened species [

12]. Despite this, positive signs of the return of wildlife to the property were observed, including the presence of lions, which were previously presumed absent. The wild dog was also regularly monitored, but the overall wildlife density in the park remained low, and the situation of the elephants was particularly precarious, with only one individual observed periodically. Although the presence of park staff had reduced poaching, it remained a significant threat to the area. The mission also expressed concern about a gold exploration license granted near the property, as it posed risks to chimpanzee habitats and threatened to pollute the Gambia River. The mission recommended updating corrective measures and retaining the property on the List of World Heritage in Danger. It defined eight indicators for the Desired State of Conservation for the removal of the NKNP from the List of World Heritage in Danger (DSOCR) by 2018, including safeguarding emblematic species, combating poaching and encroachment, setting up an ecological monitoring program, and implementing a traffic control system inside the park. Additionally, it recommended updating and implementing the property’s management plan, permanently closing the basalt quarry by 2016, avoiding gold-panning activities within the NKNP, and strengthening cooperation with the communities bordering the property. The World Heritage Committee, in its Decision 39 COM 7A.13 in Bonn, adopted the updated corrective measures and the indicators of the DSOCR and determined that these indicators should be achieved by the end of 2018.

Since 2016, Senegal has been taking steps to meet the Desired State of Conservation indicators for removing the NKNP from the List of World Heritage in Danger. However, the Mako project’s environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) suggests

10 that indirect impacts of moderate importance will worsen existing issues such as poaching, illegal gold prospecting, and habitat fragmentation. It also indicates that the loss of chimpanzee habitat outside the park will be permanent, with no identified mitigation measures. In response to the ESIA results, the World Heritage Committee, in its Decision 41 COM 7A.16, asked Senegal to take all necessary measures to ensure that the exploitation has no negative impact on the Outstanding Universal Value of the property. Continuous concerns were also raised about the Sambangalou dam project and the permanent closure of the Mansadala basalt quarry by 2018. There was an urgent need to update and implement the management plan and integrate an updated and detailed ecological monitoring program to enable the monitoring of the DSCOR indicators.

From 2016 to 2019, the World Heritage Committee acknowledged Senegal’s efforts to implement corrective measures, especially in strengthening the anti-poaching mechanism, the park staff’s capacities, and the continued income-generating activities of the local communities. The Committee requested that the State Party continue these efforts. The NKNP Management Plan (2019–2023) was approved in 2018. The 2016 and 2017 ecological monitoring results indicate viable populations of flagship species, such as the lion, wild dog, chimpanzee, and Derby eland. However, in 2017, concern was expressed that a mining concession was granted to the Mako gold prospection project for 2016–2027. In 2019, the closure of the Mansadala quarry was once again delayed. A mining license was also granted to the Barrick Gold Society, authorizing operations near the property and a mining extraction activity carried out by a company in the southeast part of the park.

From 2020 to 2023, the World Heritage Committee continued to monitor the state of conservation of the NKNP, but only two decisions were made in 2021 and 2023. The 2020 session was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the 2022 session was supposed to be held in Kazan (Russia) but was delayed due to the Russia–Ukraine conflict. During this period, there was improvement in implementing corrective measures, especially those related to monitoring key species for the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the park, combating invasive species, marking property boundaries, controlling and eliminating illicit mining, and enforcing speed limits on National Road N°7 within the property. However, serious concerns were raised about the ongoing threat to the endangered population of 15 chimpanzees in the impact zone of the Petowal Mining Company (PMC), the damage to the aquatic habitat, and a significant increase in suspended sediments in the Gambia River due to illegal mining. The Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Barrick Gold mining project identified major potential impacts on the property’s OUV and its surroundings, but Senegal did not approve the project. In 2023, financing for the Sambangalou dam was secured, and construction began, raising concerns about its potential impacts on the property’s OUV, particularly on the Gambia River’s hydrological regime downstream and the distribution of large and medium-sized mammalian fauna. A joint World Heritage Centre/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission was then requested in 2024 to assess the property’s conservation status, including progress on the above issues, the implementation of updated corrective measures and recommendations from the 2015 Reactive Monitoring mission, and the progress toward achieving the Desired State of Conservation for the removal of the property from the List of World Heritage in Danger (DSOCR). The following section analyzes the progress made by Senegal and its technical and financial partners in achieving the indicators of the DSOCR of the NKNP based on the findings of the joint UNESCO/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission report.

3.2. Brief Assessment of the State of Conservation of NKNP in 2024 Leading to Its Removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger

The 2024 joint UNESCO/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission took place in March 2024 to assess the implementation of corrective measures and indicators for the DSCOR adopted in 2015. According to the report [

13], the park’s anti-poaching system was operational and included air and ground resources. Joint ground and air surveillance operations were conducted with the Senegalese armed forces in 2022 and 2023, with an average of 12 h of flying over the NKNP. This arrangement increased the patrol effort by acquiring a ULM aircraft and four drones for the protected area. However, it was noted that the drones acquired were not robust enough to have sufficient flight autonomy over the entire park. Additionally, there were still relatively poorly covered areas due to difficulty in access, particularly to the west of the park. An emergency program to combat invasive species restored four ponds: Oudassi in 2022, Simenti, Kountadala, and Nianaka in 2023. Furthermore, 89 km of track was completed to rehabilitate impassable tracks, allow access throughout the season to the southern half of the property, and combat illegal gold mining and poaching. UNESCO and IUCN [

13] concluded that the country strengthened the park’s ecological monitoring system from 2015 to 2023, contributing to several direct and indirect observations of threatened species crucial to the property’s Outstanding Universal Value (lion, Derby eland, elephant, chimpanzee, and wild dog). However, the 2019–2023 General Management Plan has expired and needs urgent updating. Installing around 33 pastoral boreholes in village territories in the Tambacounda, Kolda, and Kédougou regions helped minimize incursions of domestic livestock into the property and strengthen its integrity. Nevertheless, the presence of cattle was confirmed at the Mansadala quarry inside the NKNP. In 2024, 102 boundary stones out of 188 were used to mark 60% of the park’s boundaries satisfactorily. A road control system, comprising physical barriers and awareness-raising materials, can be observed at the Diénoudiala and Niokolo guard posts, significantly reducing the risk of wildlife accidents. In 2023, two large-scale missions were carried out to remove gold panners from the Kérékonko and Malapa sites, reinforcing the property’s integrity [

13]. A surveillance post was also set up at Tambanoumouya to continue the drive to eliminate traditional gold panning in the park. The Mansadala quarry, covering around 40 ha, representing 0.004% of the park’s surface area, is still open for public utility purposes, and the rehabilitation resulting from mining has not started, despite the commitment made by the State Party to close it in 2012. Concerning the Sambangalou dam, several field surveys have been carried out, along with studies into possible impacts on the park. A preliminary analysis from UNESCO and IUCN [

13] suggests that when the infrastructure is impounded, there could be potential indirect negative impacts, particularly on the distribution of large and medium-sized mammalian fauna, as well as changes to the park’s habitat due to changes in the River Gambia’s hydrological regime. An in-depth analysis of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) is being carried out by IUCN to conclude whether the park’s Outstanding Universal Value has been effectively considered regarding the potential negative impacts of the dam project. In terms of strengthening cooperation with the park’s neighboring communities, the evaluation shows that the property’s management team continues to improve its relations with the adjacent communities by promoting development actions. However, more local people must be included in the park’s management body. Finally, a partnership has been established with Niokolodge, a private tourism operator contributing to conservation activities. Within this framework, an area of around 5 hectares in the Oudassi pond, which had been completely invaded by

Mimosa pigra, has been rehabilitated. An additional guard post around 500 m from the lodge has also been built to control poaching, as well as an observatory to inventory wildlife in the concession area [

14].

The evaluation of the eight indicators established in 2015 for the Desired State of Conservation for the removal of the NKNP from the List in Danger showed that, since 2018, apart from the elephant (which is in a critical situation and for which little data is available), the other characteristic species of OUV are present in the property. However, their presence does not allow us to conclude that they are viable. Regarding the chimpanzee situation in the Petowal Mining Company impact zone, fresh nest counts and individual identification from camera trap images contribute to assessing the minimum group size. At the first site (Assirik), 454 fresh and recent nests were recorded in 75 nest groups, compared with 510 nests of all age classes (fresh, recent, old, and rotten) in 190 nest groups at the second site. These results were achieved with contributions from various partners, including the Mako Project, the Zoological Society of London, and Panthera. The population size and density of flagship species are shown in

Table 1 below.

Table 2 below illustrates the trend in the number of arrests. The data show that despite similar patrol efforts in 2021 and 2023, the number of arrests for poaching offenses is decreasing. In 2022, patrol efforts decreased due to staff assignments. Nevertheless, poaching remains the most prevalent threat in 2023, accounting for 19 cases.

Despite efforts to strengthen anti-poaching measures, raise awareness among local populations, and construct 36 hydraulic infrastructures around the park to facilitate the watering of domestic livestock, livestock incursions have occurred about 10 km inside the property, particularly at the Mansadala quarry. This affects the park’s integrity and could negatively impact its Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). In anticipation of the 46th session of the World Heritage Committee, the Minister for the Environment and Ecological Transition, in correspondence no. 001754, dated 19 July 2024, reaffirmed Senegal’s commitment to permanently close the Mansadala quarry and commence rehabilitation efforts. Acknowledging Senegal’s progress in implementing corrective measures and achieving the indicators of the DSOCR, the World Heritage Committee, during its 46th session in New Delhi (India), adopted Decision 46 COM 7A.54, thereby removing the Niokolo-Koba National Park (Senegal) from the List of World Heritage in Danger after 17 years.

Specific measures that were crucial for achieving this successful outcome can be summarized in two key points: (i) the increased synergies among the national authorities responsible for managing the park, the various financial and technical conservation partners operating in the landscape, and the local communities, all working collaboratively to meet the required indicators for the Desired State of Conservation for the site’s removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger; and (ii) the strong political commitment of July 2024 to address conservation issues due to development projects, including the promise to close the basalt quarry (the Mansadala quarry) located within the NKNP.

Figure 2 summarizes the evolution of the conservation status of the Niokolo-Koba National Park from its inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2007 to its removal in 2024. The species icons in the figure illustrate conservation milestones rather than actual species succession or replacement.

In March 2024, a joint UNESCO/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission assessed the conservation status of the NKNP and the impacts of development projects that led to the NKNP’s inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Recognizing the ongoing need to protect the park, four main recommendations were adopted based on the findings of the joint UNESCO/IUCN Reactive Monitoring mission conducted in March 2024. These recommendations should be the short-term conservation priorities for the Niokolo-Koba National Park in the post-World Heritage List in Danger era.

First, Senegal should ensure that the park’s Development and Management Plan is urgently updated and implemented in a participatory and inclusive manner. This plan should include an operational ecological monitoring plan targeting the characteristic species of OUV. Secondly, the management team should document the observed upward trend in the park’s characteristic species of the OUV through a census of the wildlife species to establish a new baseline for monitoring further recovery of the OUV. Then, it is required to immediately and definitively close the Mansadala basalt quarry and provide a validated and implemented rehabilitation plan. It is also important that park governance become more inclusive by formally involving local populations in decision-making and revenue-sharing. Finally, Senegal should provide the World Heritage Committee with the necessary and sufficient guarantees for mitigating potential indirect negative impacts on the park resulting from modifying the hydrological regime caused by the filling of the Sambangalou Dam.

As demonstrated in the case of the NKNP, the Reactive Monitoring process of the World Heritage Convention remains relevant for countries to ensure the removal of sites from the List of World Heritage in Danger. It ensures that adequate and proactive measures are taken to protect and promote heritage sites. When a country has a site inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger, it is encouraged to implement appropriate legal, scientific, technical, administrative, and financial measures. This process begins with the development of indicators for the Desired State of Conservation for Removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger (DSOCR), in collaboration with the World Heritage Centre and the relevant advisory body (in particular the IUCN for natural World Heritage sites). Subsequently, the country should work closely with all relevant stakeholders to fully implement the necessary corrective measures to achieve the indicators of the DSOCR. In the case of the NKNP, Memorandums of Understanding were established between the park management authorities and various stakeholders, including conservation NGOs, universities, the private sector, and community organizations. These agreements aim to support the country’s efforts in documenting and achieving the indicators of the DSCOR, as well as mitigating the impacts of development projects on the site’s integrity. Regular meetings, chaired by the park management authorities, provide a platform for informing stakeholders about the challenges involved in implementing corrective measures. For example, collaboration with the private sector (such as Niokolodge) enables the park management authorities to secure resources for wildlife monitoring activities and community development projects. Furthermore, the gradual involvement of local communities in park management helps combat the spread of invasive species. In addition to collaborating with local communities, conservation partners, universities, and private sector actors to enhance park management, strong political will played a crucial role in the successful removal from the List in Danger. This included the important decision to close the Mansadala basalt quarry.

Finally, since the inscription of a site on the World Heritage List, countries must refrain from taking any deliberate actions that could directly or indirectly harm their own heritage or that of another State Party to the Convention. They are also expected to provide the World Heritage Committee with information regarding the implementation of the Convention and the state of conservation of their sites.

4. Discussion

The long time needed for the NKNP (17 years) to be removed from the List of World Heritage in danger follows approximately the timeline indicated by Setyawati et al. [

21] for other natural World Heritage sites. The authors noted that the previous removals of natural World Heritage sites took an average of 9 years (between 2 and 21 years). This variability highlights the complex and context-dependent nature of efforts to remove properties from the List of World Heritage in Danger. It also illustrates the significant risk that States Parties take in allowing protected areas (PAs) to deteriorate and the considerable time it takes for these areas to return to normal status. This case study also shows that removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger process does not necessarily imply a return to previous levels of wildlife populations. However, the role of the List of World Heritage in Danger as a tool for mobilization and support emphasized by Badman et al. [

22] is confirmed. These authors highlighted that, despite the long-standing presence of particular sites on the List of World Heritage in Danger, this recognition has served as a key source of support for the PAs concerned, which have thereby received special and ongoing attention from the World Heritage Convention and the broader international community. As observed for the NKNP, this designation has thus provided sustained international support and intervention, contributing to conservation efforts and recovery initiatives.

Additionally, the dual role of the Danger List is reflected in the analysis by [

3], who described the List of World Heritage in Danger as a “fire alarm,” effectively galvanizing resources to mitigate threats and prevent irreversible harm to listed sites. At the same time, this list can also serve as a regulatory and disciplinary function by employing a “naming and shaming” strategy to hold States Parties accountable for non-compliance with conservation obligations. These processes certainly played a role in our case study. However, this approach has been controversial, as several countries have directly challenged such disciplinary measures, arguing that they infringe on the principle of state sovereignty [

3].

The inscription and subsequent removal of the NKNP from the List of World Heritage in Danger also demonstrates that the park’s integrity is threatened by activities originating from the State Party itself, such as allocating mining permits in protected areas and poorly planned dam and road projects. Improved coordination between relevant ministries could have minimized these threats and eventually reduced the time the property had spent on the Danger List. Additionally, it indicates that the State Party values the evaluations of UNESCO, IUCN, and World Heritage status, recognizing them as effective conservation tools and as a strong international diplomatic instrument. Lastly, it underscores the need for increased investment in conservation structures, such as surveillance, ecological monitoring, and community development, to fulfill the State’s responsibilities.

The case of the NKNP also illustrates the positive impact of diversified partnerships involving international, regional, and local technical and financial partners (such as the European Union), NGOs (such as Panthera, the Zoological Society of London, the ULB cooperation, or Am be Koun), universities (such as ULiège), as well as the private sector (such as the Niokolodge) on conservation efforts. Thus, it is important to emphasize that the successful removal of the NKNP from the List of World Heritage in Danger was the result of coordinated action by those multiple key stakeholders. First and foremost, the national government of Senegal, through its Ministry of Environment and Ecological Transition, particularly the Directorate of National Parks, played a central role in initiating crucial policy decisions, securing funding, and committing to close high-impact sites such as the Mansadala quarry. Then, the management team led on-the-ground implementation, including anti-poaching patrols, ecological monitoring, and restoration projects, in collaboration with its technical partners in the field, previously mentioned. Furthermore, local communities, though initially marginalized, increasingly contributed to conservation through surveillance, control of livestock incursions, and participation in alternative livelihood programs supported by hydraulic infrastructure and community outreach efforts. International stakeholders, on the other hand, including UNESCO, IUCN, and the European Union, provided technical expertise, periodic monitoring, and essential financial support. Finally, the private sector partners, such as Niokolodge, directly invested in habitat restoration and local conservation incentives, showing how ecotourism can support ecological and social outcomes. This multi-level, cross-sectoral collaboration underpinned the park’s governance transformation and progress toward the achievement of some key indicators of the desired state of conservation.

Similar to Senegal, States Parties must fulfill their primary responsibility to protect World Heritage sites situated on their territories, in conformity with Article 4 of the World Heritage Convention, ensuring that conservation efforts are prioritized over economic interests. Similar challenges are observed in other endangered sites in Africa, where conservation challenges, poaching, logging, and development pressures—rather than armed conflict—threaten the integrity of protected areas. This was the case for the Rainforests of the Atsinanana (Madagascar), where timber trafficking and poaching had threatened biodiversity for the past decade [

23], until increased efforts by the State Party and its partners turned around the overall situation and better controlled the pressures on the property, leading to its removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger at the 47th session of the World Heritage Committee in July 2025 in Paris. On the other hand, these challenges are still observed in sites such as the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve (Côte d’Ivoire/Guinea), facing pressures from mining projects in Guinea [

24], and the Selous Game Reserve (United Republic of Tanzania), where a dam project endangers wildlife [

25].

According to the State of Conservation information system (

https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/, accessed on 15 June 2025), six natural World Heritage sites have been removed from the World Heritage in Danger list over the past decade. These sites are similar to the NKNP, as they also experienced significant human interference and illegal development:

Los Katíos National Park (Colombia) was removed from the List in Danger in 2015, after concerns about its integrity due to increased deforestation in the surrounding region and potential threats from large-scale infrastructure projects had been addressed.

The Simien National Park (Ethiopia) was taken off the List in Danger in 2017 after responding to substantial declines in the populations of the Walia ibex, Ethiopian wolf, and other large mammals, compounded by agricultural encroachment at the park’s borders and the impacts of road construction within the area.

The Comoé National Park (Côte d’Ivoire) was removed from the List in Danger in 2017, after enduring a political and military crisis in Côte d’Ivoire from 2002 to 2010, alongside challenges such as wildlife poaching, fires caused by poachers, overgrazing by large cattle herds, and the absence of an effective management strategy.

The Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System (Belize) was removed from the List in Danger in 2018, after efforts were made to reverse the sale and lease of public lands for development within the park, which led to the destruction of vital mangrove and marine ecosystems.

The Salonga National Park (Democratic Republic of Congo) was removed from the List in Danger in 2021 after addressing the impacts of an increase in poaching and illegal encroachment that compromised the site’s integrity.

The Rainforests of the Atsinanana (Madagascar) were removed from the List in Danger in 2025, after having significantly addressed two major challenges over the past decade: (i) illegal logging of valuable wood species, which contributed to the deforestation in the Andohahela, Masoala, and Marojejy National Parks; and (ii) poaching of endangered lemurs, which are key to the site’s Outstanding Universal Value.

In all cases, striking a balance between development and conservation becomes crucial for safeguarding these irreplaceable natural sites, and effective coordination among national governments, the private sector, and international bodies remains essential to safeguard the Outstanding Universal Value of these sites. In the case of the NKKP, challenges for the future still need to be considered: on the one hand, the real involvement of elected community representatives in the park’s governance structure and the implementation of mechanisms for sharing tourism revenue with communities, and on the other, effective monitoring and preventive measures against the growing jihadist phenomenon on the Senegal–Malian border. In addition, future research should focus on the following: the most endangered and key species of the site’s Outstanding Universal Value; the persistent interest of mining companies trying to establish projects in this area despite its international designations; the ecological evolution of rehabilitated sites; and the demographic trends and the human development indicators in the park’s surrounding areas.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

The case of the Niokolo-Koba National Park (NKNP) represents a significant conservation success in Africa, illustrating the transformative impact of long-term commitment, collaborative governance, and adaptive management in overcoming complex conservation challenges. The 17-year process culminating in the site’s removal from the List of World Heritage in Danger underscores both the severity of anthropogenic threats faced and the potential for recovery through persistent, evidence-based action.

Three key governance innovations underpin this success. First, the integration of local, national, and international actors, through formal mechanisms such as the Memoranda of Understanding, created a robust multi-stakeholder governance framework that ensured consistent implementation of corrective measures. Second, the deployment of a multi-indicator ecological monitoring system (targeting species of OUV, integrity, and management) facilitated targeted responses to dynamic threats and enabled the documentation of gradual ecological improvements. Third, the political commitment demonstrated by the State Party, especially through its 2024 promise to close the Mansadala quarry, played a catalytic role in aligning development projects with conservation obligations.

In addition, the conservation of the NKNP required substantial financial investment. Notably, the Government of Senegal launched a three-year Emergency Plan between 2011 and 2014, investing approximately EUR 4.57 million (XOF 3 billion). Additional funds and technical support were provided by UNESCO (through its International Assistance Fund and Extrabudgetary initiatives), the European Union, IUCN, and various conservation NGOs and universities. Beyond direct ecological benefits, these investments brought returns in terms of international prestige, strengthened diplomatic ties, increased potential for ecotourism revenue, and reduced vulnerability to environmental degradation.

This study also makes two original contributions. Methodologically, it demonstrates a practical application of the Desired State of Conservation for Removal (DSOCR) framework as an adaptive policy tool in non-conflict heritage contexts. Empirically, it highlights the NKNP as one of the rare sub-Saharan parks to achieve delisting without being impacted by armed conflict, offering a comparative baseline for similar protected areas under different governance or threat profiles.

To broaden the relevance of these findings, we compare the NKNP with other delisted African sites, such as Comoé and Salonga National Parks, which faced similar development and ecological threats. Common success factors include enhanced surveillance, closure of extractive activities, improved community relations, and robust international support. However, the NKNP stands out in the explicit use of participatory field missions and decentralized surveillance infrastructure. These mechanisms may be particularly adaptable in settings where conservation challenges stem from governance gaps rather than armed conflict.

While the NKNP’s removal from the Danger List marks an important milestone, future sustainability depends on strengthening local participation in governance (including revenue sharing), continuous monitoring of flagship species, preventive measures against the growing jihadist phenomenon on the Senegal–Malian border, and mitigation of the indirect impacts of the Sambangalou Dam. We recommend the urgent updating of the Management Plan with embedded performance tracking systems for each DSOCR indicator to establish clear causal links between interventions and outcomes. Additionally, international frameworks should encourage more systematic cross-site comparative research to refine generalizable strategies tailored to different heritage and ecological contexts.

In conclusion, the NKNP provides a replicable model for conservation success through long-term governance innovation, but its lessons must be contextualized to achieve broader application across the World Heritage system. Safeguarding natural heritage under pressure requires not only technical solutions but also institutional resilience, inclusive governance, and sustained political will.