Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do tourists perceive the watermills, and what kind of triggering moments could be identified in the process of tourism development utilising pre-industrial heritage?

- (2)

- How do local people and NGOs get involved in the usage of, and tourist activities related to, the watermills, and what are the factors constituting (pre-)industrial tourism as a new sectoral growth pole of the region?

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

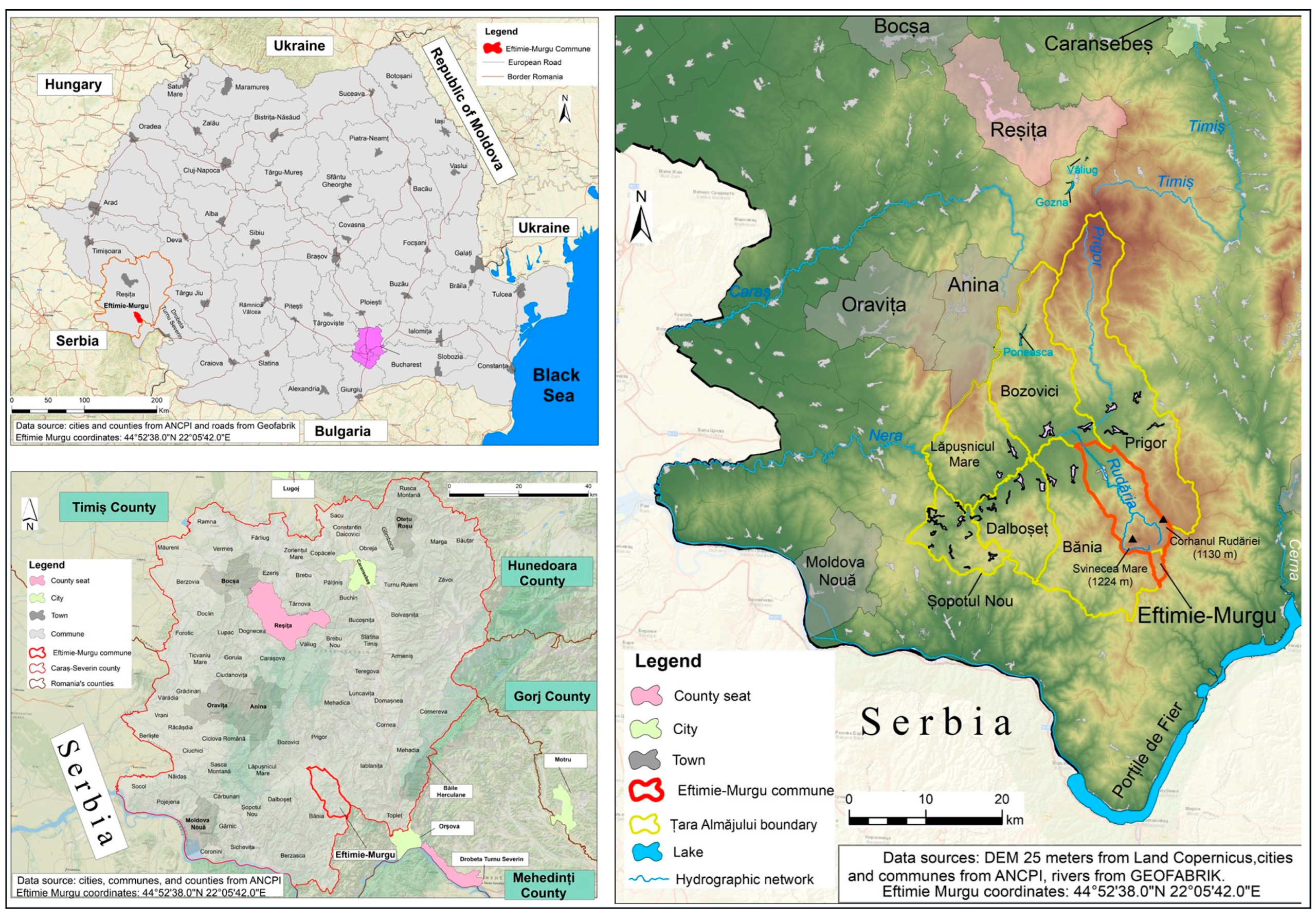

4. Study Area

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Profile and Degree of (Dis)Satisfaction of Tourists with the Rudăria Watermills

5.2. The Role and Importance of the Rudăria Watermills

5.2.1. The Link between the Rudăria Watermills and the Recent Past

- (1)

- The moment in the 2000s of the massive renovation project of the mills as a collaboration project with the Astra National Museum from Sibiu, and the declaring of the Rudăria Valley as a protected area [49], is the first trigger event by which an increasing concern for organic and slow tourism has been generated in the region;

- (2)

- The rapid growth of tourism at the nearby Bigăr waterfall in the 2010s put the Rudaria Watermills as a second tourist destination in the area;

- (3)

- The ‘colour the village’ event, developed by an NGO outside the county (i.e., houses in the village were painted in their original colours by hundreds of volunteers) in 2019 led to more interest of tourists in the village and in the watermills too;

- (4)

- The coronavirus pandemic (2020–2022) diminished the flows of tourists to the mills, which has led to a current trend of better conservation.

5.2.2. The Perceived State of Heritage Conservation and Restoration of the Rudăria Watermills

5.2.3. The Role of Watermills for the Community

5.2.4. The Role of Watermills as Pre-Industrial Technologies for Tourism Development

5.2.5. Future of Pre-Industrial Tourism Development and the Need for Intelligent Promotion of Tourism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, S.; Chi, O.H.; Martinez, S.D.; Lu, L. When “Old” Meets “New”: Unlocking the Future of Innovative Technology Implementation in Heritage Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 10963480231205767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hognogi, G.; Popa, A.; Oprea, D. Rural tourism and its role in the sustainable development of rural areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, B. Cultural Turism as a Mean for Capitalization of Industrial Heritage for Economic Regeneration of Former Mining Areas. Rev. Transilv. De Ştiinţe Adm. 2013, 2, 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. Geography is Everywhere: Culture and Symbolism in Human Landscapes. In Horizons in Geography; Gregory, D., Walford, R., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hognogi, G.G.; Marian-Potra, A.C.; Pop, A.M.; Mălăescu, S. Importance of watermills for the Romanian local community. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijulie, I.; Matei, E.; Preda, M.; Manea, G.; Cuculici, R.; Mareci, A. Tourism-a viable alternative for the development of rural mountainous communities. case study: Eftimie Murgu, Caras-severin county, Romania. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2018, 22, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntele, I.; Iațu, C. Tourism Geography. Concepts, Methods and Forms of Spatio-Temporal Manifestation; Sedcom Libris Publishing: Iasi, Romania, 2003. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Cercleux, A.-L.; Sorensen, A.; Merciu, F.-C.; Saghin, I.; Paraschiv, M.; Secăreanu, G.; Săgeată, R.; Ianoș, I. Community re-creating of a small industrial town in Southeast Europe: Lessons from Fieni, Romania. Mitteilungen Der Osterr. Geogr. Gesellschaf 2022, 164, 311–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fajer, M. Watermills—A forgotten river valley heritage. Selected examples from the Silesian voivodeship, Poland. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nadalipour, Z. Understanding of the cultural heritage landscape from perception to reality. Art Civiliz. Orient 2016, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Korsgaard, S.; Müller, S.; Tanvig, H.W. Rural entrepreneurship or entrepreneurship in the rural—Between place and space. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2015, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Creative destruction or creative enhancement? Understanding the transformation of rural spaces. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A.; Shannon, M. Exploring cultural heritage tourism in rural Newfoundland through the lens of the evolutionary economic geographer. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 59, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Covaci, R.N. Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania. Identities 2022, 30, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood Chavez, D.F.; Niewiadomski, P.; Jones, T. Interpath relations and the triggering of wine-tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 1874–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Evolutionary economic geography: Reflections from a sustainable tourism perspective. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. The post-industrial landscapes of Riotinto and Almadén, Spain: Scenic value, heritage and sustainable tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2016, 12, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Ispas, R.T.; Crețan, R. Recent Urban-to-Rural Migration and Its Impact on the Heritage of Depopulated Rural Areas in Southern Transylvania. Heritage 2024, 7, 4282–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierała, T.; Leśniewska-Napierała, K.; Nalej, M.; Pielesiak, I. Co-Evolution of Tourism and Industrial Sectors: The Case of the Bełchatów Industrial District. ESR P 2024, 29, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.; Halkier, H.; Sanz-Ibáñez, C.; Wilson, J. Advancing evolutionary economic geographies of tourism: Trigger events, transformative moments and destination path shaping. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 1819–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Baláž, V. Tourism in Transition: Economic Change in Central Europe; I.B.Tauris: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Kask, T. Transforming tourism spaces in changing socio-political contexts: The case of Pärnu, Estonia, as a tourist destination. Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 452–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C.; Wilson, J.; Anton Clavé, S. Moments as catalysts for change in the evolutionary paths of tourism destinations. In Tourism Destination Evolution; Brouder, P., Clavé, S.A., Gill, A., Ioannides, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Lungu, M.A. Neglected and Peripheral Spaces: Challenges of Socioeconomic Marginalization in a South Carpathian Area. Land 2024, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glemain, P.; Bioteau, E.; Dragan, A. Les finances solidaires et l’économie sociale en Roumanie: Une réponse de «proximités» à la régionalisation d’une économie en transition? Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2013, 84, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacal, P.; Cocoș, I. Geography of Tourism; Dep. Ed.; Poligrafic ASEM: Chișinăm, Moldova, 2012; 227p. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Jonsen-Verbeke, M. Industrial heritage: A nexus for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekes, J.F.; Buda, D.M.; de Roo, G. Adaptation, interaction and urgency: A complex evolutionary economic geography approach to leisure. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Priestley, G.; Blanco, A. Rural tourism in Spain: An analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum 2004, 35, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Urban-rural migration, tourism entrepreneurs and rural restructuring in Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagüe Perales, R.M. Rural tourism in Spain. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrić, L.; Mandić, A. Visitor management tools for protected areas focused on sustainable tourism development: The Croatian experience. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 13, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R. Sustainable tourism and policy implementation: Lessons from the case of Calviá, Spain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, T.E. Finding meaning in sustainability and a livelihood based on tourism: An ethnographic case study of rural citizens in the Aysen Region of Chile. In Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports; West Virginia University Repository: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2006; p. 8884. Available online: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8884 (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Fleischer, A.; Pizam, A. Rural tourism in Israel. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çorapçıoglu, G. Documentation Method for Conservation of Industrial Heritage: Mediterranean Region Water Mill Example. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on the Conservation of Monuments in the Mediterranean Basin; Koui, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Chapter 26; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Iorio, M.; Corsale, A. Rural tourism and livelihood strategies in Romania. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CORINE Land Cover. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/d08852bc-7b5f-4835-a776-08362e2fbf4b (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Geofabrik Open Street Maps Database. Available online: https://www.geofabrik.de/data/download.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- National Agency for Cadastre and Real Estate Advertising, Bucharest. 2024. Available online: https://geoportal.ancpi.ro/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests, Bucharest. 2024. Available online: https://www.mmediu.ro/categorie/date-gis/205 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSSE. Statistical Data in Caras-Severin County, Romanian Institute of Statistics, Bucharest. 2024. Available online: https://statistici.insse.ro/ (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Ianăș, A.N. Ţara Almăjului. Studiu de Geografie Regională [The Land of Almăj. Study of Regional Geography]; Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iurkiewicz, A.; Horoi, V.; Popa, R.M.; Drăgușin, V.; Vlaicu, M.; Mocuța, M. Groundwater vulnerability assessment in a karstic area (Banat Mountains, Romania)—Support for water management in protected areas. In Water Resources and Environmental Problems in Karst Conference; Cvijic: Belgrade, Serbia, 2000; pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Eftimie Murgu Commune Town Hall. 2024. Available online: www.primariaeftimiemurgu.ro (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Moșoarcă, C. Water Mills from Rudăria—The Place Where Time is Grinding. Available online: http://www.descopera.ro/descopera-in-romania/9835110-morile-de-apa-de-larudaria-locul-unde-se-macina-timpul (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Sava, C.; Petroman, C.; Maksimović, M. Rudăriei gorges—Steps towards the development of sustainable tourism. Quaestus 2019, 14, 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Manescu, C.; Sirb, N.; Mateoc, T.; Sarb, G.; Raicov, M.; Gşa Caius, I. Using water as a renewable energy resource. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, S138–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, F.; Karimian, H.; Talebian, M. Water mills: Socio-economic structure in Hawraman mountain region during Qajar and Pahlavi period. Soc. Hist. Stud. 2023, 12, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Szatten, D.; Brzezińska, M.; Maerker, M.; Podgórski, Z.; Brykała, D. Natural landscapes preferred for the location of past watermills and their predisposition to preserve cultural landscape enclaves. Anthropocene 2023, 42, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myga-Piątek, U. Cultural Landscape. In Evolutionary and Typological Aspects; Uniwersytet Slaski: Katowice, Poland, 2015; 393p. [Google Scholar]

- Vashisht, A.K. Current status of the traditional watermills of the Himalayan region and the need of technical improvements for increasing their energy efficiency. Appl. Energy 2012, 98, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Beek, P. The effects of political fragmentation on investments: A case study of watermill construction in medieval Ponthieu, France. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2010, 47, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caple, C. Conservation Skills: Judgement, Method and Decision Making; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; 247p. [Google Scholar]

- Price, N.; Talley Kirby, M.; Melucco Vaccaro, A. Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage (Readings in Conservation); Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1996; 520p. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, A.; Osipova, E.; Lafrenz Samuels, K.; Caldas, A. World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate; United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, Franch, 2016; 108p. [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Valipour, M.; Dietrich, J.; Voudouris, K.; Kumar, R.; Salgot, M.; Mahmoudian, S.A.; Rontogianni, A.; Tsoutsos, T. Sustainable and Regenerative Development of Water Mills as an Example of Agricultural Technologies for Small Farms. Water 2022, 14, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyatsi, A.M.; Mwendera, E.J. The contribution of informal water development in improving livelihood in Swaziland: A case study of Mdonjane community. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2007, 32, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, K.; Thakur, R.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S. Feasibility analysis for conversion of existing traditional watermills in Western Himalayan region of India to micro-hydropower plants using a low head Archimedes screw turbine for rural electrification. Int. J. Ambient. Energy 2022, 43, 7463–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Sustainable Rural Technologies; Green Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; WU, D.C. Tourism productivity and economic growth. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L.; Harfst, J.; Ilovan, O.-R. Cultural Values, Heritage and Memories as Assets for Building Urban Territorial Identities. Societies 2022, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Clark, L. Tourism and Economic Growth; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Hu, D.; Swanson, S.R.; Su, L.; Chen, X. Destination perceptions, relationship quality, and tourist environmentally responsible behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, G.B.; McIntosh, A.J.; Zahra, A.L. Tourism and spirituality: A phenomenological analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.H.; Rein, I. Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry, and Tourism to Cities, States, and Nations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; 400p. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.; Voogd, H. Selling the City: Marketing Approaches in Public Sector Urban Planning; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S.J.; Connell, J. Tourism: A Modern Synthesis, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; 634p. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.K. Tourism, Culture and Regeneration; CABI, Digital Library: Wallingford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A. Education and post-communist transitional justice: Negociating the communist past in a memorial museum. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2019, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Crețan, R.; Dunca, A. Museums and transitional justice: Assessing the impact of a memorial museum on young people in post-communist Romania. Societies 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism in Europe; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2005; 254p. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism: Rethinking the Social Science of Mobility; Pearson Education Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; 468p. [Google Scholar]

- Nistor, M.M.; Nicula, A.S.; Dezsi, Ş.; Petrea, D.; Kamarajugedda, S.A.; Carebia, I.A. GIS-Based Kernel Analysis for Tourism Flow Mapping. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2020, 11, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, M.M.; Nicula, A.S. Application of GIS Technology for Tourism Flow Modelling in The United Kingdom. Geogr. Tech. 2021, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding: Glocal, Virtual and Physical Identities, Constructed, Imagined and Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anholt, S. Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Oancea, O.A. Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage 2024, 7, 4354–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Sustainable Tourism: Theory and Practice; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006; 256p. [Google Scholar]

- Rojek, C. Ways of Escape: Modern Transformations in Leisure and Travel; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C. War as a Tourist Attraction: The Case of Vietnam. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; 489p. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Holtorf, C. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: Archaeology as Popular Culture; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003; 325p. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Wang, D.; Jia, C.H. Virtual reality and attitudes toward tourism destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Schegg, R., Stangl, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, A.; Cretan, R.; Bulzan, R.D. The spatial development of peripheralisation: The case of smart city projects in Romania. Area 2024, 56, e12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicula, A.S.; Stoica, M.S.; Bîrsănuc, E.M.; Man, T.C. Why Do Romanians Take to the Streets? A Spatial Analysis of Romania’s 2016–2017 Protests. Rom. J. Political Sci. 2019, 19, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart Tourism Destinations Enhancing Tourism Experience Through Personalisation of Services. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, M.; Sieg, P. Tourism Development in Post-Industrial Facilities as a Regional Business Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Grubor, B.; Banjac, M.; Đerčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Šmugović, S.; Radivojević, G.; Ivanović, V.; Vujasinović, V.; Stošić, T. The Sustainability of Gastronomic Heritage and Its Significance for Regional Tourism Development. Heritage 2023, 6, 3402–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interview Code | Age Group | Gender | Education Level | Position | Born in Eftimie Murgu? | Lives in Eftimie Murgu? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 60–70 | M | High school | Former mayor | Yes | Yes |

| I2 | 50–60 | M | University | Mayor | Yes | Yes |

| I3 | 50–60 | M | PhD | Former mayor | Yes | Yes |

| I4 | 40–50 | M | University | Local councillor, engineer | Yes | Yes |

| I5 | 20–30 | M | University | Priest | No | Yes |

| I6 | 50–60 | F | University | Local councillor, guesthouse administrator | Yes | Yes |

| I7 | 30–40 | M | University | Public servant | Yes | Yes |

| I8 | 40–50 | F | University | Restaurant administrator | Yes | Yes |

| I9 | 40–50 | F | University | Guesthouse administrator | Yes | Yes |

| I10 | 40–50 | M | University | Local councillor | Yes | Yes |

| I11 | 40–50 | M | University | Secretary | Yes | Yes |

| I12 | 40–50 | M | High school | Local councillor | Yes | Yes |

| I13 | 60–70 | M | High school | Former local councillor | Yes | Yes |

| I14 | 50–60 | F | University | Merchant | Yes | Yes |

| I15 | 40–50 | M | University | Former pastor | No | No |

| I16 | 50–60 | M | University | Accountant | No | No |

| I17 | 40–50 | F | University | Teacher | Yes | No |

| I18 | 40–50 | M | University | Commercial director, local councillor | Yes | No |

| I19 | 40–50 | M | University | NGO president | No | No |

| I20 | 30–40 | M | University | Public servant | Yes | Yes |

| Analysis: Selected Themes And Sub-Themes | Major Results |

|---|---|

| Quantitative analysis of tourists’ perceptions Theme no 1: Tourists’ perceptions of the watermills Sub-theme 1 Profile and degree of (dis)satisfaction of tourists with the Rudăria Watermills | The Rudăria Watermills attract a significant number of tourists from across Romania, but the international dimension of this tourist attraction is relatively limited. |

| The majority of tourists do not select the mills as a specific destination; rather, they are included as part of a broader tour. | |

| The highest satisfaction rate among tourists is not associated with the mills themselves, but rather with their interactions with local residents and their products. | |

| In particular, tourists have expressed concerns regarding the availability and clarity of information, the condition of facilities and infrastructure and the overall cleanliness of the area. | |

| Qualitative analysis of local people and NGOs Theme no 2: The role and local tourism importance of the Rudăria Watermills Sub-theme 1: The link between the Rudăria mills and the recent past | Watermills have historically fulfilled a multitude of roles, including as a source of sustenance, providing food for humans and animals alike. Watermills have served as a form of organisation, both in the construction and maintenance of the mills themselves and in the organisation of the milling process. The major trigger event for the tourist development of the watermills was the transition from communism to capitalism. Among post-communist second-level trigger events, we noticed: The 2000s moment of the massive renovation project of the mills (as a collaboration project with the Astra National Museum from Sibiu) is the earliest trigger event by which an increasing concern for organic and slow tourism has been generated in the region; The rapid growth of tourism at the nearby Bigăr waterfall in the 2010s put the Rudaria Watermills as a second tourist destination in the area; The ‘colour the village’ event (i.e., houses in the village were painted in their original colours by hundreds of volunteers) in 2019 led to more interest of tourists in the village and in the watermills too; The coronavirus pandemic (2020–2022) diminished the flow of tourists to the mills, which has given birth to a current trend of better ecological conservation of the mills. |

| Sub-theme 2: The conservation and restoration of the Rudăria Watermills | A significant conservation and restoration project has recently been undertaken on a large scale at the mills. This project has been carried out in collaboration with a local association, with input from local residents, and with the benefit of expert advice from a museum. |

| Sub-theme 3: The role of the mills for the community | Mills can be regarded as an intergenerational pivot due to their dual status as a tangible and sentimental heritage. Mills continue to serve as a means of both identifying with one’s heritage and promoting the local community’s ecological flour and are used for subsistence and even for making some profit. |

| Sub-theme 4: The role of watermills as pre-industrial technologies for local tourism development | As interest among tourists in pre-industrial technologies increased, so too did tourist activity in the village. This has generated significant media exposure, yet the village has not become a full-fledged tourist destination. Tourists most often visit the mills but do not usually extend their stay in the village due to the scarcity of accommodation units in the area. |

| Sub-theme 5: The future of pre-industrial tourism development and the need for the intelligent promotion of tourism in the Rudăria Watermills | The mills appear to be gaining traction organically, akin to a snowball gaining momentum. Notable or concerted forms of international and online media promotion have yet to emerge. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Terian, M.I. Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context. Heritage 2024, 7, 4790-4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090227

Dragan A, Crețan R, Terian MI. Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context. Heritage. 2024; 7(9):4790-4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090227

Chicago/Turabian StyleDragan, Alexandru, Remus Crețan, and Mădălina Ionela Terian. 2024. "Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context" Heritage 7, no. 9: 4790-4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090227

APA StyleDragan, A., Crețan, R., & Terian, M. I. (2024). Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context. Heritage, 7(9), 4790-4813. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090227