1. Introduction

Ethnographic and historical museums play a crucial role in representing the past, while contemporary museums are concerned with the concepts of modern or modernism and do not offer elements of the past to the public. Preserving and documenting a way of life that is disappearing or has vanished is always a challenging task for any museum. Every museum is defined by its collection. Ethnographic and historical museums preserve traditional, tangible and intangible heritage, and their mission is to collect works of art that were created under different social, cultural, religious and political conditions. Furthermore, there are differences between urban and rural lifestyles and how these are interpreted and presented to the public. Therefore, ethnographic museums need to develop viable and feasible concepts or methods for displaying the ethnographic view of the rustic environment and the everyday realities of rural life that are compatible with the museum’s available space and budget.

The modern ethnographic museum must adapt to a broader public and take on new responsibilities. It is encouraged to be creative and strive to respond to local needs and fulfil the wishes of local and international visitors. They must become true custodians of heritage, taking care of the preservation of a rapidly disappearing material culture and the human knowledge and skills that created it.

Visiting a museum can be a unique experience, yet visitors often take for granted the intensive work, knowledge and enthusiasm invested in the design and layout of the museum’s exhibition. Depending on the type of museum objects, there are various requirements and challenges when displaying three-dimensional textile objects, which are subject to strict professional rules. For example, objects that are stored flat must be exhibited in a three-dimensional form. Since clothing is designed to fit a human body, it is also very important that the three-dimensional textile objects are displayed in an appropriate manner to create a uniform yet distinctive appearance for the entire collection. Selecting appropriate mannequins, shaping them to fit a particular garment, and positioning them to create an ambience that conveys the intended story and meaning of an exhibition is a challenging task.

Mannequins and torsos come in many shapes, styles, sizes, finishes, materials and prices. The choice of mannequin and the best display techniques will depend on whether art, history, fashion, anthropology or ethnology is being exhibited [

1,

2]. The mannequins purchased for the display of museum objects often may not match the shape and proportions of the garment to be exhibited on them and must therefore be adapted to its specific cut, dimensions and shape [

3]. In addition, the materials used for display must be of museum quality and sustainable.

An example that illustrates the challenges of exhibiting ethnographic costumes is the interinstitutional project to replace the display mannequins in the Ethnographic Museum of Dubrovnik. Dubrovnik Museums consist of four specialised individual museums housed in important heritage buildings: the Cultural History Museum in the Rector’s Palace, the Maritime Museum in Fort St John and the Ethnographic Museum in the old civic granary [

4]. The Archaeological Museum lacks space to display a permanent exhibition. Each museum has rich collections that tell the story of the cultural, historical, traditional, tangible and intangible heritage of the city of Dubrovnik and the area of the former Dubrovnik Republic.

The existing mannequins in the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik were not entirely acceptable for display. It was therefore decided to gradually replace them with more suitable ones while respecting the strict code of ethics, professional standards and competencies of the conservation–restoration profession. The project “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes” took place over two consecutive years (2018–2019). The aim was to replace the existing mannequins, raise awareness of the importance of cultural heritage and educate students, colleagues and the general public on how to display ethnographic costumes, which can be a demanding undertaking. The focus was on effective collaboration between institutions as an example of good practice and heritage care. Out of a total of 17 display mannequins from the museum’s permanent exhibition needing to be replaced, to date, 6 have been adapted in these workshops.

2. The Use of Mannequins: The Past and the Present

The selection of an adequate mannequin system support raises questions about the advantages and disadvantages of the older style, straight and rigid mannequin versus the newer style, flexible mannequin that helps to create a more natural and desirable posture. The function of an iron rod is to support the mannequin, and it can be used with both straight and flexible mannequins. Some museums paint the lower exposed part of the iron rod using the same colour as the exhibition floor to make it discreet or hide it from public view [

5].

There is a difference between the display of folk costumes and fashion. Ethnographic costumes may share some characteristics with fashionable clothing, but their primary purpose is to reveal the way of life and customs of a region or country. Folk costumes are considered to belong to the field of ethnology and ethnography, while fashionable clothing is considered an expression of art history. Consequently, ethnographic clothing as an expression of geographical locations and social structures is placed outside the fashion discipline [

5]. Traditional clothing follows certain conventions to express the sensorial, emotional, social, anthropological and phenomenological aspects of wearing these clothes—rules that should be followed when exhibiting in a museum.

The appropriate display of historical and ethnographical textiles contributes to better and longer preservation of these sensitive objects of cultural heritage, and emphasises the visual impression and artistic experience of the object. For example, in tailoring, a garment is made according to the structure and proportions of the human body for which it is sewn. In the museum, on the other hand, the mannequin must be sculptured to match the shape of the garment. The shape and dimensions of a mannequin affect the quality of the presentation of a three-dimensional garment. In order to preserve the intrinsic shape of a garment, it must not be fitted too tightly or too loosely on a mannequin [

3].

3. The Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik and the Mannequins of the Sculptor Zvonimir Lončarić (“Riba”)

The granary building that houses the Ethnographic Museum was built in 1590. The four-storey building contained fifteen storage pits on the ground floor and spaces for drying grain on the upper floors. It remained the state granary until the fall of the Republic in 1808. The colloquial name “Rupe” (The Holes) is derived from the vernacular term for underground grain silos carved into the rock or tufa [

6]. The granary entered the twentieth century as a damaged structure requiring reconstruction. Thanks to the efforts of individuals and the Dubrovnik Society for the Development of Dubrovnik and its Surroundings (DUB), the building was used from 1940 used as a museum space for the exhibition of intangible and tangible heritage display (for a part of the exhibition on Dubrovnik seafaring in the Middle Ages) and later as the Lapidarium of the Archaeological Museum [

4,

7].

The Ethnographic Museum was established at the beginning of the twentieth century and began with a collection of objects of traditional culture. Later, a schoolteacher, Jelka Miš (1875–1956), significantly expanded the collection by donating traditional folk clothing and needlework [

8]. The first permanent ethnographic exhibition in Fort St John was opened in the mid-twentieth century. Since then, a workshop for textile preparators has also been in operation. In 1953, the Commission for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia donated 805 objects (textiles and handicrafts) to the Dubrovnik Museum for the new permanent exhibition of the Ethnographic Department. In 1954, the ethnologist Antun Kalameta organised an exhibition entitled Folk Arts of Yugoslavia [

9]. This exhibition was open to the public until the renovation of the building after an earthquake in 1979 [

4]. The National Art of Yugoslavia consisted of 1400 exhibits from different areas and techniques of folk art. In the period 1949–1952, the exhibition visited several European cities: London, Edinburgh, The Hague, Amsterdam, Zürich, Oslo, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Brussels, Paris and Geneva [

10].

A significant part of the Ethnographic Museum’s holdings consist of textiles, which are arranged in ten collections and include traditional clothing from the Dubrovnik region, Croatia, and neighbouring countries. The concept and layout of the museum’s permanent collection date back to 1991 and were partly based on a synopsis of the collection created by the ethnologist Dr Katica Benc Bošković in 1985 [

11]. The ground floor of the museum shows the storage of grain in situ. On the first floor, traditional economic activities are exhibited together with traditional rural architecture and house interiors from the Dubrovnik area. On the second floor, examples of clothing and jewellery ornaments worn on festive occasions from small villages in the Dubrovnik region are on display. Particularly valuable are the unique examples of textile handicrafts from the second half of the nineteenth century. The storage and presentation of textiles in a historical building present some problems due to fluctuations in humidity and temperature [

12].

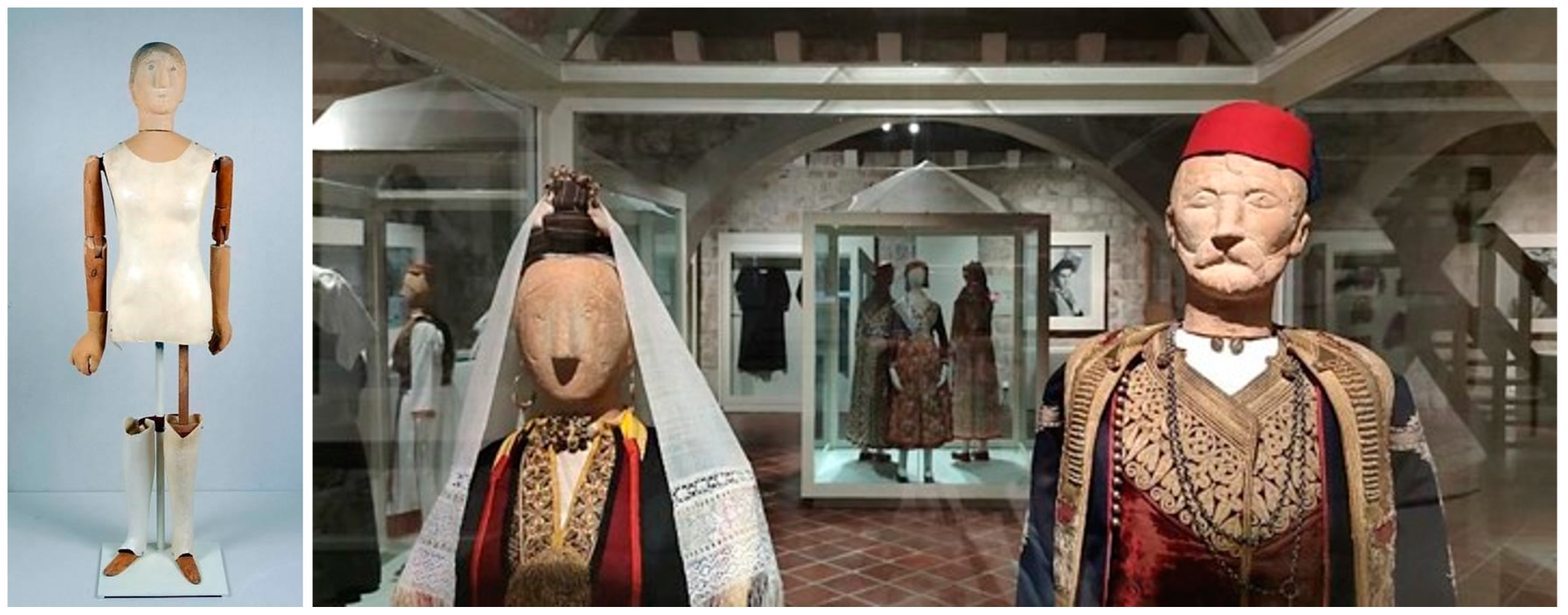

The museum’s furnishing and the mannequins used to display the clothing reflect the guidelines for the presentation of the material that the museum established in the 1980s. Mannequins created by the academic sculptor and printmaker Zvonimir Lončarić, nicknamed “Riba”, were made for the permanent exhibition of the Ethnographic Museum in 1991 (

Figure 1).

The museum mannequins made by Lončarić provided a complete representation of the traditional way of dressing. They had moveable limbs, and it was possible to authentically display the lower parts of the clothing (trousers, socks, toe warmers, gaiters, shoes and sandals). The greatest value of the mannequins lies in the artist’s design of the heads and faces, on which the headpieces, essential components of the traditional manner of dress, could be displayed. The faces of the mannequins are sculpted from terracotta based on the facial features of the people in rural regions. For this reason, the museum considered them to be protected works of art in the permanent exhibition. Furthermore, the uncommon selection of materials used to construct them is what makes them distinctive and unique: terracotta for the hands and heads, acrylic resin for the torso and wood and metal parts for the limbs and joints.

The samples of these materials were analysed by the Natural Science Laboratory of the Croatian Conservation Institute [

13,

14]. Unfortunately, organic chemicals released as gases from these materials caused mechanical damage and discoloration to the textiles, as documented in a conservation and restoration report [

14]. This situation required urgent preventive measures to suppress further deterioration of the material. As a long-term solution, it was decided to replace the mannequins made by the artist Lončarić with new ones. Following recommendations from conservator–restorers about the best way to display the restored textiles, the replacement of the museum mannequins made by sculptor Lončarić began in 2018. Due to the artist’s interpretation of the faces of the local population and the choice of material from which they were made, they are valorised as cultural property and preserved as a testimony of the time.

4. The Interinstitutional Project of Replacing Display Mannequins

When preventive conservation measures were carried out on the textiles in 2009, changes were detected on the textiles that had been in direct contact with the original mannequins. As mentioned above, they were made of various organic and inorganic materials, and direct contact with these harmful materials increased the rate of degradation.

Moreover, the textiles that came into direct contact with the mannequin covered with acrylic paint bonded to the mannequin’s body. Conservation measures were implemented to mitigate the damaging effects, such as removing certain parts of the mannequin (the metal, wooden and ceramic parts of the limbs) and protecting the torso with cotton undershirts and acid-free tissue paper. Since then, a more intensive cooperation has begun with the University of Dubrovnik, the Department of Art and Restoration, the Croatian Restoration Institute and the textile departments in Zagreb and Ludbreg. These institutions urged the replacement of those old, inadequate mannequins. In 2018, after completing a series of conservation projects within the collection, it was decided to gradually replace the existing mounts (six display cases and a total of 17 mannequins) with new museum-quality mannequins.

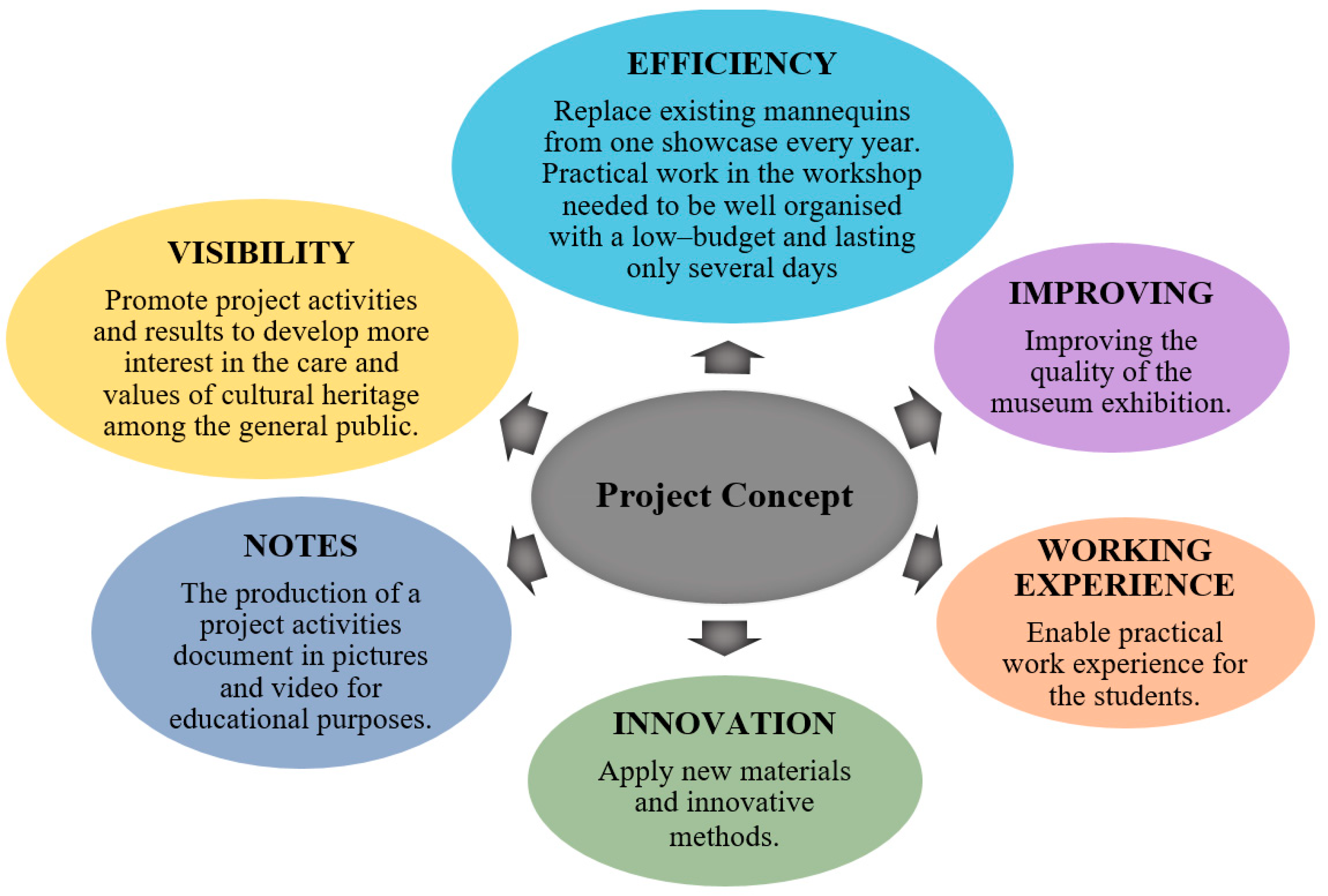

It has taken many years to find solutions on how to exhibit valuable three-dimensional textile objects while meeting a number of requirements, such as the museum experience and the curatorial story presented to the public, all in accordance with conservation and restoration guidelines. The “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes” project developed a solution that meets a number of criteria and objectives to better display and protect cultural heritage (

Figure 2). The project was organised by the Textile workshop of the Department of Art and Restoration at the University of Dubrovnik, in cooperation with the Croatian Conservation Institute and Ethnographic Museum of Dubrovnik Museums. Two project-based learning workshops took place on the premises of the Textile Conservation and Restoration Workshop at the University of Dubrovnik.

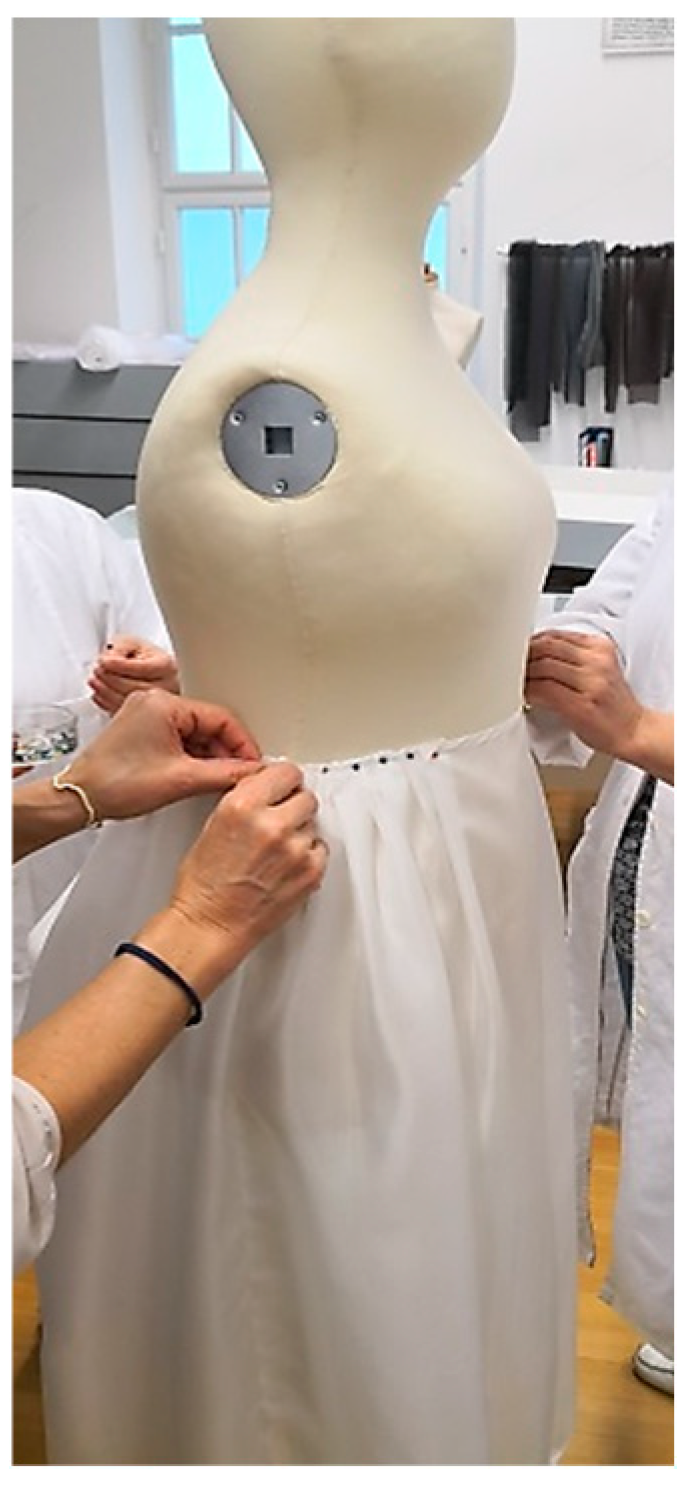

In order to be able to exhibit hats, hair accessories and shoes, it was important that the replacement mannequins have arms, legs and a head. The Ethnographic Museum purchased Polystar soft and flexible mannequins made of polyurethane foam with a plastic-coated surface (

Figure 3,

https://www.polyform.de/slim-line/; Accessed 18 November 2020). Another advantage of the Polystar mannequins is the detachable hands system, which allow easier handling of the garments during trials and final mounting [

15]. To shape the mannequin’s body, one should take good measurements of the costume size. In some cases, it is necessary to dress the mannequin with the original costume; therefore, a replica of a specific garment is made to preserve the original [

3,

15].

4.1. Project Phases

Each project phase was characterised by a distinct set of activities (

Figure 4). In the first phase (16 October 2018–19 October 2018), three female mannequins were modified for three ethnographic costumes, and in the second phase (4 November 2019–8 November 2019), two female and one male mannequin were modified for three ethnographic costumes (

Figure 3). Each workshop began with educational lectures by an interinstitutional team of textile conservators on making museum-quality mannequins, accompanied by examples and followed by practical work in the workshop.

4.1.1. Phase 1: Modifying Three Female Mannequins for Three Ethnographic Costumes

The first workshop “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes” took place according to the framework of the European Year of Cultural Heritage, from 16 October 2018 to 19 October 2018 (

Figure 4a). On the first day, a series of lectures were held. The lectures began with the history of the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik and present-day insights into the museum’s exhibitions and experiences. This was followed by topics dealing with professional guidelines and problems related to the display of three-dimensional textiles and the use of different materials for the production and design of mannequins, which were complemented by case studies. In the first phase of the project, a workshop was held to modify three special mannequins for the display of three different ethnographic ceremonial women’s costumes from Župa, Rijeka Dubrovačka and Dubrovačko primorje (Dubrovnik Littoral). These valuable and unique ethnographic garments are characterised by a baroque cut that appeared in traditional costumes at the end of the nineteenth century.

4.1.2. Phase 2: Modifying Two Female and One Male Mannequin for Three Ethnographic Costumes

The second phase took place between 4 and 8 November 2019 (

Figure 4b). While during the first workshop, only female mannequins were modified during the first workshop, the focus in this workshop was on the male type of mannequin. Female mannequins wearing long dresses can easily be attached to a stand with a metal holder, with the pole hidden from view. However, the male version, which wears wide pants that end just below the knees, requires a different approach. The construction used a method in which the mannequin hangs from an external support placed behind the mannequin and hidden between the different layers of the costume. The balance and stability of the mannequin and all additional materials therefore required special attention [

16]. In order to secure them properly and not damage the objects, Ivan Mladošić, a stone restorer from the Dubrovnik Museums, made custom-made metal supports for the female and male display mannequins for this occasion. The traditional female costumes selected for this phase of the project did not include headscarves, as these posed a unique challenge to design and make special wigs that could faithfully reproduce the art of traditional hairstyles and wedding headdresses [

17].

The accompanying lectures, which took place at the University of Dubrovnik, covered a range of topics on effective methods of preparing ethnographic costumes for display, mounting costumes for exhibition, various support systems and the care and presentation of museum exhibitions. Practical work also took place in the workshop for textile conservation and restoration at the University of Dubrovnik. An exhibition of posters on the workshop’s topics took place simultaneously on the University’s campus.

4.2. Practical Work: Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes

Modifying a mannequin for the display of three-dimensional objects requires specialised knowledge, skills and competencies, and this project offered its participants the opportunity to develop these criteria.

The specialised Polystar mannequins purchased by the Dubrovnik Museums were modified to exhibit various ethnographic costumes from the Ethnographic Museum’s collection. Each ethnographic costume was sewed for a specific individual. To replicate that unique body shape, custom padding techniques had to be applied. According to the garment’s shape and size, layers of polyester wadding were applied to the mannequin’s body (

Figure 5). Prior to that, polyester wadding was thoroughly cleaned to remove any deposit materials such as apertures, adhesives or impurities. Building up the torso by adding layers of wadding until it is exactly the right shape and size to fit the garment is a very challenging task. It is best to apply the padding to the front and back of the torso, rather than the sides. After the first fitting, the padding was sewn directly onto the soft mannequin body using a large, curved needle. The applied layers of polyester wadding adapted to the shape and size of the garment. The mannequin’s face and hands were also shaped in proportion to the size of the torso so that it could wear certain decorations on its head and hold an apple in its hands (

Figure 5).

After the second fitting and any final alterations or additions to the padding, the mannequins were covered with plain dyed, four-way stretch fabric, with a soft touch (

Figure 6). It was light beige, cotton jersey knit fabric blended with elastane. The prewashed fabric was cut into two pieces, one to cover the front and one for the back side of the torso, neck and head. Covering the entire torso with stretch fabric requires considerable skill and knowledge of how to handle the fabric to ensure a perfect fit. The fabric was then pinned to the mannequin with the wrong side facing outwards. This way, the hem of the fabric remains hidden when it is turned inside out. The position of the pins was marked, and the positioning lines of the fabrics were also marked with tailor’s chalk, which served as a guide during the sewing process. The front and back pieces were also marked and then sewn together using an overlock stitch. The new cover was placed over the mannequin, and the bottom edge was finished with a hand stitch.

In addition to shaping the body of the mannequin, there were other challenges for displaying ethnographic costumes, such as:

Making a silk petticoat to hold the silhouette of an ethnographic costume (

Figure 7): A petticoat was needed for a skirt from the collection and the workshop participants learned how to sew one suitable for the skirt. To add volume to the skirt, they had to determine the right amount of fabric for the petticoat, and how to shape and sew the pleats. This was a valuable task for the participants to learn.

Making a custom metal support for the male mannequin (

Figure 8): As the male costume includes trousers and shoes, finding the most suitable solution to fix the mannequin to the stand was necessary. The metal support was made from a straight rod, on which a “C” shaped rod that encircles the mannequin’s waist is attached to the end. The lower, round part of the metal stand came with the mannequin, and the rod was made of stainless steel and customized to support display mannequins. The challenge lay in how to secure the metal rod to a male mannequin wearing pants and at what height and shape. The rod around the mannequin’s waist was concealed in the various layers of the costume without compromising the aesthetics or damaging the textile. As it is not ideal for metal to be in contact with textiles, the rod was covered with protective material.

Creating hair and styling it into shapes encapsulating traditional hairstyles suitable for exhibiting hats and hair accessories. (

Figure 9): The participants were not familiar with the methods or materials for making a wig. For this purpose, a crafting technique was invented that involved knotting and knitting wool threads in different shades of brown to achieve hairstyles that reflected those of the period.

Shaping arms and legs. All ethnographic costumes have the appropriate shoes, and some female mannequins have decorative props to hold in their hands (

Figure 10). For an authentic display of ethnographic costumes, all mannequins’ body parts had to be shaped correctly. Padding the mannequin’s arms and legs in proportion to the torso was a challenging task. To achieve the desired shape and size, layers of wadding were wrapped around the fingers and legs. As there are limits to the extent that costumes can be manipulated, the detachable and flexible arms of the Polystar mannequins proved to be useful for the fitting and shaping process.

4.3. The Project’s Educational Value

The educational workshops made an important contribution by highlighting the value of textile heritage and emphasizing the significance of safe and effective costume mounting for long-term heritage preservation. The workshops provided a rare opportunity for students and colleagues from various institutions to practice costume mounting techniques and develop innovative solutions for displaying textile objects. In addition to conservation and restoration students, experts from other institutions, such as the Linđo Folklore Ensemble from Dubrovnik, the Ethnographic Museum of Zagreb and the Varaždin City Museum, participated in the workshops. All participants from the University of Dubrovnik received certificates of participation. The project generated public interest and media coverage, with local and national television stations, newspapers, and local and institutional websites publishing stories about the project.

5. Conclusions

This case study highlighted the challenges of exhibiting diverse ethnographic costumes by discussing past presentation methods and how new solutions have been implemented conforming to the modern conservation–restoration profession. The mannequins initially used in the Ethnographic Museum were created by the artist Zvonimir Lončarić (“Riba”). These mannequins’ accentuated body parts, made of different materials, for example, the hips, shoulders, legs and arms, expressed the artist’s poetic nature. However, they were not practical for displaying ethnographic costumes. Therefore, with the project “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes”, the gradual process of replacing the mannequins commenced. It was a demanding and challenging task, particularly the aspects of producing a customized metal support for the male mannequin and making the hair for hairstyles to exhibit head accessories. Ten mannequins created by Zvonimir Lončarić can still be seen in the permanent exhibition; the workshops have replaced six. Preventive conservation measures were carried out on the existing mannequins: the hands, which were made of ceramic and metal elements, were removed and the torso and legs were covered with high-quality conservation materials and insulated.

The educational workshops significantly contributed to promoting the value of textile heritage and the importance of contemporary, safe and effective costume mounting as a long-term heritage preservation measure. It was an exceptional education and training opportunity for the students and colleagues from other institutions to practice costume mounting methods and develop new solutions to display unique textile objects. Furthermore, the project contributed to advancing interinstitutional collaboration between cultural heritage institutions such as Dubrovnik Museums, the Art and Restoration Department of the University of Dubrovnik, and the Croatian Restoration Institute. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this project was suspended; however, the project partners wish to continue the collaboration and address further issues related to the permanent museum exhibition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; methodology, D.J.; validation, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; formal analysis, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; investigation, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; resources, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; data curation, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.J.; writing—review and editing, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; visualization, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K.; supervision, D.J.; project administration, D.J., B.M. and M.M.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on the official Youtube channel of the local Dubrovnik television (DUTV) at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRMRgLhy5eM. The data regarding original mannequins presented in this study is published in the Conservation-restoration report and is available on request from the Croatian Conservation Institute (

https://www.hrz.hr/en/index.php/opi-podaci/kontakt-2). The original contributions on the issue of original mannequins presented in the study are included in the article Vraničić, M. Preventive Protection of Textile Material on Exhibition Mannequins in the Permanent Display of the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik, Dubrovnik Museums Miscellany 2015, Number III, Dubrovnik, Croatia, p. 327–334. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors due to copyright policy of the University of Dubrovnik.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our special gratitude to our colleagues Gordana Car and Branka Regović from the Croatian Conservation Institute for their valuable guidance throughout the practical work and for sharing their longstanding experience and knowledge. We deeply appreciate their permanent support, work ethic and constant optimism.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fajardo, S.; Flecker, L.; Gatley, S.; Miller, K. Mounting Historic Dress for Display; Dress and Textile Specialists: London, UK, 2015; p. 14. Available online: https://www.dressandtextilespecialists.org.uk/dats-toolkits/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Cooks, R.B.; Wagelie, J.J. Mannequins in Museums: Power and Resistance on Display; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Flecker, L. A Practical Guide to Costume Mounting; Butterworth–Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 13, 17+45–48+79. [Google Scholar]

- Dabelić, I. The Developmental Path of Dubrovnik Museums from 1872 to 2002. Dubrov. Mus. Misc. 2004, 1, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Riegels Melchior, M.; Svensson, B. Fashion and Museums: Theory and Practice; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2014; pp. 117+119. [Google Scholar]

- Kipre, I. Rupe Granary: Granaries and the Storage of Grain in Dubrovnik; Dubrovnik Museums: Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2014; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Menalo, R. Historical Development of the Archaeological Museum. Dubrov. Mus. Misc. 2004, 1, 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Benc–Bošković, K. The Teacher Jelka Miš in Ethnological and Museum Work. Ethnogr. Mus. Doc. 1996, 2, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Marunčić, T. They Created Dubrovnik museums. Dubrov. Mus. Misc. 2022, 5, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Šepić, D. Izložba narodne umjetnosti Jugoslavije/Exhibition of national art of Yugoslavia. Slov. Etnogr. 1953/1954, 6/7, 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dunatov, L.J. The permanent exhibitions of the Dubrovnik museums. Dubrov. Mus. Misc. 2022, 5, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Foekje, B.; Brokerhof, A.; Van den Berg, S.; Tegelaers, J. Unravelling Textiles: A Handbook for the Preservation of Textile Collections; Archetype Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Vraničić, M. Preventive Protection of Textile Material on Exhibition Manikins in the Permanent Display of the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik. Dubrov. Mus. Misc. 2015, 3, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Regović, B. Report on Conservation and Restoration Works Carried Out on Parts of Female Traditional Attire from Župa Dubrovačka, Skirt–Shirt, Inv. No. 1079D and Shirt Inv. No. 1079C from the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik; Croatian Conservation Institute: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch, J.; Stolleis, K. Kölner Patrizier–und Bürgerkleidung des 17. Jahrhunderts: Die Kostümsammlung Hüpsch im Hessischen Landesmuseum Darmstadt; Abegg–Stiftung: Riggisberg, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Niekamp, B.; Jucker, A.W.; Bloh, J.C.V.; Jolly, A. Das Prunkkleid des Kurfürsten Moritz von Sachsen (1521–1553) in der Dresdner Rüstkammer: Dokumentation Restaurierung Konservierug; [The Magnificent Dress of Elector Moritz of Saxony (1521–1553) in the Dresden Armoury: Documentation, Restoration and Conservation]; Abegg–Stiftung: Riggisberg, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.; Gatley, S. Keep Your Hair On: The Development of Conservation Friendly Wigs. Conserv. J. 2011, 59, 2–3. Available online: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/conservation-journal/spring-2011-issue-59/keep-your-hair-on-the-development-of-conservation-friendly-wigs (accessed on 5 August 2024).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).