Abstract

Transhumance and its associated heritage are extremely complex and dynamic systems, and their conservation requires the analysis of interdisciplinary factors. To this end, fuzzy cognitive maps (FCMs) and Delphi surveys were applied for the first time in the field of heritage conservation. The model was applied to the tangible and intangible transhumance heritage of Andorra to determine its current state of conservation and to evaluate strategies for its preservation. Two panels of experts worked on the development of the model. Five experts with profiles related to conservation and transhumance heritage formed the first panel, which designed the preliminary FCMs, while seven experts in Andorran cultural heritage (panel 2) adapted the preliminary FCM model to Andorran transhumance heritage using Delphi surveys. The FCM model allowed us to analyze the influence of different variables on the conservation of transhumance heritage and to assess policy decisions. Further studies will focus on the implementation of this model in other countries to establish common recommendations for the conservation of the cultural heritage of transhumance.

1. Introduction

Transhumance is one of the oldest human activities linked to pastoral practices, involving the seasonal movement of livestock along routes from cold areas to warmer ones and back according to the needs of the animals. This activity had an important economic impact in the Middle Ages and was the main economic driver for many rural communities. Currently, in Europe, lowland pastures are frequently privately owned, while mountain pastures are often jointly managed by governance bodies. Agricultural intensification in lowland areas, together with other social motivations, such as a lack of vocational training, the low economic profitability of the activity, or a lack of infrastructure, among others, is causing an outmigration from pastoral areas and the aging of rural populations [1]. Aside from generating products, transhumance is very important in the protection of mountainous areas and natural heritage and helps to conserve cultural heritage. This cultural heritage is varied, from tangible heritage such as infrastructures (farms, walls, roadways, bridges, oratories, etc.) or tools employed by shepherds to intangible heritage related to ways of living and relating to nature. The conservation and management of tangible and intangible heritage requires interdisciplinary research based on diverse academic domains, for example, ecology, anthropology, geography, agronomy, sociology, environmental science, economics, and cultural studies. This is due to the fact that transhumance, as a living form of heritage, is an extremely complex and dynamic system that has evolved as a reflection of social and cultural changes. The complexity of this system is mainly related to a bidirectional human–nature relationship in which shepherds obtain resources for their socioeconomic activity and in return care for the environment and its biodiversity. Although this relationship could be anchored in time, it is strongly influenced by multiple and diverse factors, such as new land uses, the low profitability of economic activity, or climate change, among others, that could upset this balance.

Preventive conservation could be one of the most important measures to be taken by governments or conservation stakeholders. This strategy attempts to anticipate potential adverse events. Methodologies have been developed based on multi-hazard assessments in urban, rural, or coastal environments [2,3]. However, these methodologies usually focus on changes over time and/or catastrophic events [4,5], sometimes using indexes [6,7,8] to set priorities and facilitate decision-making by stakeholders. Nevertheless, in the case of a complex and dynamic system such as transhumance, methodologies must take into account its broad overview to allow for the analysis of both hazards and opportunities in the conservation of this centuries-old form of cultural heritage. Adapting methodologies that take into consideration the hypothetical evolution of variables that influence conservation could help stakeholders to implement conservation management. Furthermore, including the opinions of experts in the field of cultural heritage conservation would guarantee the identification of these variables and highlight their importance in this complex and dynamic system.

This study aimed to determine the current state of conservation of transhumance heritage in Andorra and to evaluate strategies for its preservation. To do so, it was necessary to analyze the transdisciplinary factors that affect the conservation of transhumance heritage. This study was designed with three specific objectives. The first was to discuss the anthropogenic, economic, and governance factors that affect the conservation of this form of natural and cultural heritage, as well as its main natural hazards, in an international team, and to establish an initial approach using fuzzy cognitive maps (FCMs). The second objective was to evaluate and adapt this preliminary FCM approach to the tangible and intangible heritage of transhumance in Andorra with the help of local experts. To this end, FCMs and Delphi surveys were used to analyze and predict the state of conservation of transhumance heritage in multi-scenario studies. Finally, different scenarios specific to Andorra were tested to discuss the model’s applicability to stakeholder decision-making.

Transhumance in Andorra

The proposed methodology is validated in this case study of transhumance heritage in Andorra. Andorra (Europe) is a microstate with an area of 468 km2 located in the heart of the Pyrenees. It is a parliamentary co-principality presided over by two co-princes: the President of the French Republic and the Bishop of La Seu d’Urgell. Andorra is divided into seven municipalities, each with its own local administration (the Comú), and has special relationships with its neighboring countries (Spain and France).

In Andorra, transhumance has been a common practice for centuries, and its mountains, covered by vast meadows, have allowed animal grazing to be the main source of income. Although it is now a marginal activity, transhumance used to be an economically and territorially complex activity, which has left a cultural and social heritage of inestimable value, essential for understanding the country’s history and socio-economic reality. Unfortunately, due to the gradual abandonment of traditional grazing practices, the lack of interest on the part of the government, the pressure generated by economic activities, and new land uses, which have increased over the last 60 years, part of this heritage has deteriorated, although it has not disappeared.

The world of transhumance has left some unique and relevant testimonies in Andorra, which are close to those found in a large area of the Pyrenees [9]. It is therefore clear that the French and Spanish Pyrenees share a common history of seasonal migration and traditional knowledge, as evidenced by their material and toponymic heritage [10]. The Andorran case could be used as a paradigm or model for areas that have common or similar cultural heritage and problems with its conservation.

As far as immovable heritage is concerned, there are hundreds of dry-stone buildings in the high valleys of Andorra. Among them are the typical livestock farms of the region, called “orris”. They were dedicated to the milking of sheep and the production of cheese during the summer months. Next to the “orris” there are always one or two shepherds’ huts and a sheepfold where the lambs were kept at night.

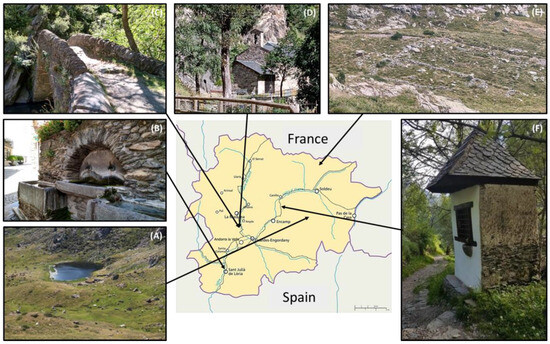

There are also structures linked to the movement of livestock through the Andorran geography (Figure 1): the traditional dry-stone walls, the bridges used to cross rivers, the drinking troughs, and the presence of crosses, oratories, and simple rural chapels that offered spiritual protection to the shepherds along the way.

Figure 1.

Map of Andorra with the main rivers, towns, and transhumant roads. Examples of immovable cultural heritage associated with the transhumance activity: (A) Orri del Cubil rebuilt. (B) Fountain and trough in Sant Julià de Lòria. (C) Bridge of Sant Antoni de la Grella. (D) Hermitage of Sant Antoni de la Grella. (E) Ruined Orri and shepherd’s huts of Cabana Sorda. (F) Oratory is located on the old Camí Ral that goes from Canillo to Meritxell.

As far as the movable heritage is concerned, it is dominated by the tools used for shepherding, such as the rucksack, the sheepskin jacket, the shepherd’s crook, the cattle bell, the branding iron, and the spiked collar worn by the shepherd’s dog to protect the livestock from possible attacks by wolves. In addition, the work of tending the livestock allowed the shepherd to make all kinds of wooden objects, such as cheese strainers, necklaces, or ladles, usually decorated with geometric, floral, astral, zoological, and religious motifs [11].

The system also includes intangible elements, such as the Andorran livestock fairs. These have their roots in the old livestock fairs that used to be held at the end of October, just before the cattle left the mountains of Andorra for the plains. Similarly, some practices that have disappeared are being recovered. This is particularly the case of the production of lump cheese called “d’Orri”, which disappeared after the 18th century due to the development of horse and cow breeding, and the art of dry-stone walling, a traditional construction method that was included in the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2018 [12].

2. Research Design

A model based on Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCMs) and Delphi surveys was tested to analyze the conservation of Andorran transhumance heritage. The interdisciplinary model includes variables involved in conservation and allows for the assessment of management decisions. This methodology could be integrated with other studies carried out by the Government of Andorra to protect transhumance and its heritage. Moreover, the similarity with other transhumance activities in French and Spanish Pyrenees makes it easy to apply this model in other studies.

FCMs are similar to conceptual maps, although much less hierarchical, in that the concepts (also called components) are related and combined to establish cause-and-effect relationships between them. Bart Kosko [13] developed them as an extension of the cognitive maps proposed by Robert Axelrod [14] ten years earlier. Kosko incorporated a non-deterministic or fuzzy approach to the cause–effect relationships between concepts [15,16].

The FCM is a tool that is widely used in various fields such as agriculture [17], environmental management [18,19], disaster planning [20], ecology [21,22,23], and urban planning [17,18,24], especially in decision-making processes, because its characteristics allow for the understanding and analysis of complex and dynamic systems.

Several people (usually experts) or a single person can create an FCM. When several people create an FCM, it becomes a much more reliable model, because each expert reflects his or her knowledge of the system in the set of concepts [13,15,25]. In contrast, when a single person constructs an FCM, it is usually based on the opinions of experts who are consulted to define concepts or decision criteria and to describe the causal relationships between the proposed concepts [26,27,28]. One of the basic ways of obtaining such opinions is through the Delphi method.

In this research, the FCM was developed using Mental Modeler software (http://www.mentalmodeler.org, accessed on 12 April 2024). Mental Modeler is an FCM-based software developed by Steven Gray and co-workers that facilitates the elaboration of the map and the automatic development of different scenarios. Specifically, the Mental Modeler was designed to allow stakeholders to construct a cognitive model, develop scenarios, and revise their models based on the model output [19].

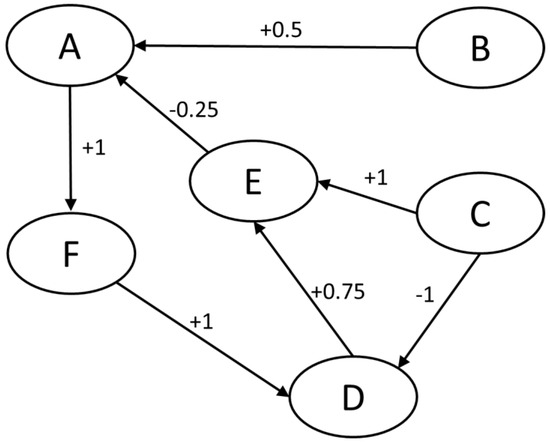

The components of the FCMs are interrelated and combined by arrows to establish cause-and-effect relationships between them. Each relationship can have a positive or negative incidence that is represented by the arrows with a plus (+) or a minus (−) sign. An arrow with a positive sign on the map indicates that a concept is causally increasing, while an arrow with a negative sign indicates that it is causally decreasing [13]. Next, each link between concepts must be numerically graded using values between −1 and 1 [15,29]. This number is called the weight, and it represents the degree of influence that one concept can have on another [16,29], as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

An example of a Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) illustrating weighted edge relationships between system concepts (A, B, C, D, E, and F). The arrows indicate the link between two concepts and its value, called weight, represents the degree of influence that one concept can have on another.

Following graph theory, the resulting FCM is translated into an adjacency matrix format [26,30,31]. This matrix contains all the values of the relationships between concepts. It also allows a static system analysis, where the most related and influential concepts can be assessed [26,31]. The results of this static analysis are often explained by the indicators of outdegree, indegree, and centrality [15,26,32,33,34]. The outdegree is the sum of the weights associated with the connectors originating from a concept. This indicates the extent of the concept’s influence on the system. In contrast, the indegree is associated with links that enter a concept, showing the extent of its dependency. Finally, centrality is the sum of the outdegree and indegree indicators and indicates the degree of involvement or importance of system concepts [26,32,34]. The values of these indicators specified for each concept determine the type of component in a map. It shows how concepts interact with other concepts. These components are drivers, receivers, and ordinary components. The driver components have a positive outdegree and a zero indegree. The receiver components have a positive indegree and zero outdegree. Ordinary components have both a non-zero indegree and an outdegree [26].

Another input parameter generated in static analysis is the density [26,35]. Density is an index of connectivity that indicates how connected or sparse the FCM is. The higher the density, the greater the potential management strategies and options for changing the behavior of the system [26]. It is important to have more options to develop semi-quantitative scenarios that allow stakeholders to understand the current and projected states of the systems represented by the FCM.

The development of the model was divided into three phases adapted to the process proposed by Infante-Moro et al. [36]: (a) construction of the preliminary FCM, (b) analysis and improvement of the FCM by local experts using Delphi surveys to weight relationships, and (c) the static analysis of the model.

2.1. Construction of the Preliminary Fuzzy Cognitive Maps

The first phase was developed in a workshop sponsored by the PECUS project (https://www.u-space.it, accessed on 12 April 2024). An international interdisciplinary team of five experts (Table 1) identified a list of concepts directly and indirectly involved in transhumance heritage conservation. The recruitment of the team was based on individual training and expertise, with professional profiles involved in different areas related to the conservation and management of transhumance heritage: architecture and territorial strategic planning, geography and landscape design, risk and vulnerability of cultural heritage and preventive conservation, conservation–restoration of dry-stone monuments, and planning of outdoor activities.

Table 1.

Profile details of the professional experts involved in preliminary FCM.

The work session objective was to identify the concepts or variables that influence the conservation of transhumance and its heritage. The brainstorming method was used, so experts freely proposed different variables and their relationships. A moderator noted every variable, and the panel agreed to clustering to avoid duplicate variables and to reduce the list of factors. Consequently, the concepts were grouped into four thematic areas. The list of variables of each thematic area was checked and the variables that referenced similar issues were clustered in a new concept that involved them. For example, the variables erosion by wind and erosion by rain were unified in a unique variable called “Erosion”; graffiti and intentional damage were unified under the variable “vandalism”. The brainstorming and cluster session took about 4 h.

The clustered variables were used to build a preliminary FCM using the Mental Modeler application. The variables were linked to each other based on the suggestions and discussions of the experts. These links were justified in the cause-and-effect relationships between two variables, that is, the influence exerted positively or negatively by one variable on the development of another variable. The values of the arrows or connectors were chosen from a discrete set between −1 and 1 to describe the strength of these links: 0.25 was considered weak, 0.5 medium, 0.75 strong, and 1.0 very strong. The correlation between concepts is linear [37,38] and could be directly proportional (positive values) or inversely proportional (negative values).

At the end of the work session, the experts built a preliminary FCM with the concepts that involved transhumance heritage conservation and the relationship between them.

2.2. FCM Analysis and Improvement by Experts

Next, the preliminary FCM was validated through a case study. In this second phase, the FCM was presented, analyzed, and adapted to the needs of the Andorran transhumance heritage by seven experts (two conservators, the head of the Department of Movable Cultural Property of Andorra, an ethnographer, a museologist, an architect, and an archaeologist). The experts were recruited based on their expertise in the management and conservation of Andorran cultural heritage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Profile details of the professional experts involved in Delphi surveys.

The panel’s knowledge of Andorran transhumance and its heritage allowed us to revise the FCM, the concepts, and their relationships to apply it to Andorra. The weight or influence of one concept on another was established through a survey developed using the Delphi method. The Delphi survey was used to avoid the prevalence of the opinion of possible leaders on the panel of experts.

The Delphi survey is an approach in which experts identify clashes of opinion through successive questionnaires [39,40,41]. The best method is to conduct anonymous surveys to avoid the influence of leaders. The quality of the results depends above all on the care taken, from the preparation of the questionnaire to the selection of the experts consulted [40,41]. At the end of each round, the results are analyzed and sent back to each expert for the next round, so that they can see their answers in relation to the global position of the group. The aim is for them to refine their initial judgment based on the opinions of the group and the reflection on their own previous choices [42].

Delphi surveys have been widely used to assess the risk and vulnerability of cultural buildings and archaeological sites [4,43,44,45,46]. The Delphi method is particularly interesting for bringing together the multidisciplinary expertise required for cultural heritage conservation–restoration in an urban or rural setting.

For this research, a survey was designed to establish the influence of the interrelated concepts of the FCM, avoiding questions that seemed to invite a yes/no answer because they would not capture the respondents’ indecision. Thus, four possible answers were proposed: very important, important, somewhat important, and unimportant.

At the end of the process, the percentages obtained in each response were weighted to obtain a value that expressed the overall importance that the seven experts attached to each question in the survey. The results were returned to each expert in a second round to see whether they maintained or changed their answers once they knew the overall opinion of the group, according to the Delphi method. Finally, the weight of each answer was calculated using Equation (1) [47].

where A%, B%, C%, and D% are the percentages of responses that consider the factor to be very important, important, somewhat important, and unimportant, respectively. The numerical values of importance (Av, Bv, Cv, and Dv) were assigned to each category as shown in Table 3. The weight of each answer synthesized the degree of the experts’ overall assessment of each question. It allowed us to weight the cause–effect relationships previously established in the cognitive map.

Weight = (A% × Av + B% × Bv + C% × Cv + D% × Dv)/400,

Table 3.

Numerical value of the categories of the assessment scale for each question.

2.3. Static and Dynamic Analysis

The static analysis makes it possible to reduce the map or the concepts proposed by experts to influence the system represented by the FCM. As discussed in Section 2.1, there are three types of connections (C) between concepts: those involving positive causality between concepts (direct proportionality; C > 0), those involving negative causality between concepts (inverse proportionality; C < 0), and those with no relationship (C = 0). Generally, the static analysis is based on the centrality value that indicates the degree of involvement or importance of each concept in the system [26,32,34], although some researchers have proposed new methods, such as Ordered Weighted Averaging (D-OWA) [48,49].

In the third phase, the new model for transhumance heritage conservation was analyzed using the indicators of outdegree, indegree, centrality, and density established by the Mental Modeler tool. The map was explained through this analysis and several simulations were carried out using the Mental Modeler scenario interface.

Additionally, the FCM allowed a dynamic analysis [50]. To run the exercises or scenarios, the main components of the FCM can be set to a value between −1 (strong negative change) and +1 (strong positive change). The changes in the system are displayed in a bar graph to show how the components might react in the scenario being studied. This is a useful tool to make decisions or predictions [51].

3. Results

3.1. The Preliminary Fuzzy Cognitive Map

Twenty-three concepts emerged from the brainstorming, which was organized into four groups or thematic areas according to their similarity (Table 4). These concepts formed the components of the FCM.

Table 4.

Concepts of the FCM emerged from brainstorming.

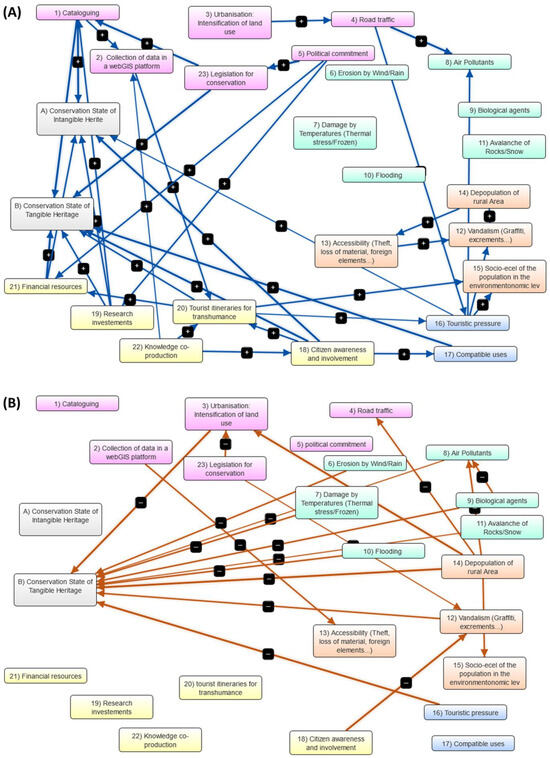

The cognitive map included two main themes: the conservation of tangible cultural heritage and the conservation of intangible cultural heritage because their differences imply different relationships with the socio-economic conditions and the environment. All concepts were grouped according to their thematic areas. Using the Mental Modeler software (http://www.mentalmodeler.org, accessed on 12 April 2024), each factor was assigned a color to make each category more recognizable. The FCM (Figure 3) was designed for the general assessment of transhumance heritage with 25 components and 55 links; hence, it needed to be adapted for each real scenario by local experts.

Figure 3.

Fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) is built through expert brainstorming to address heritage conservation. The variables were classified into five groups: governance factors (pink), natural hazards (green), anthropogenic factors (orange), others (blue), and tourism plans and others (yellow). The correlation between concepts is linear. (A) Blue lines indicate positive relationships (an increment in the concept related to the arrow origin increases the concept related to the arrowhead) between components. (B) Red lines represent negative relationships (an increment in the concept related to the origin of the arrow decreases the concept related to the arrowhead) between components.

3.2. FCM Analysis and Improvement by Andorran Experts

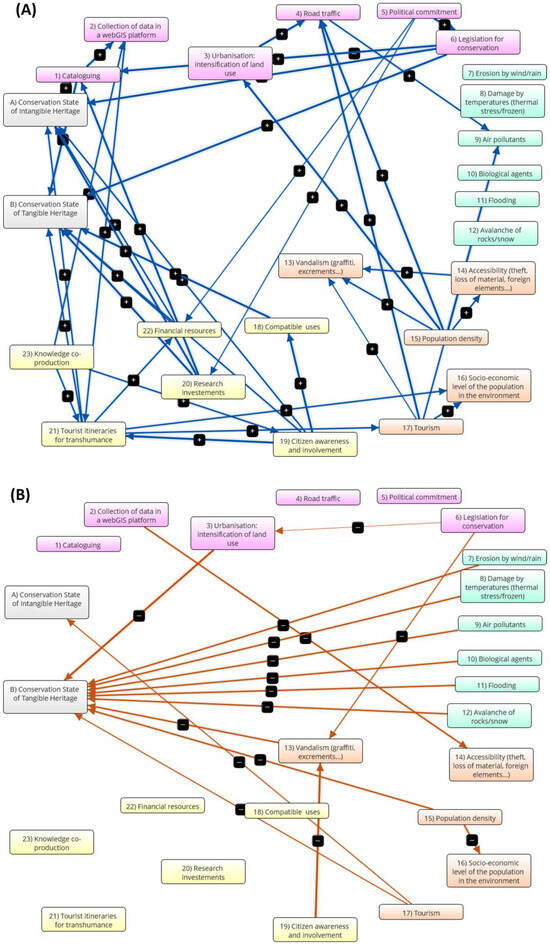

The first FCM model was analyzed, and minor adjustments were made: (1) Component number 15 (depopulation of rural areas) was changed to population density, as the phenomenon of depopulation does not exist in Andorra. (2) Component number 17 (touristic pressure) was changed to tourism. The term pressure has a negative connotation; so, it was removed to give the map a different dynamic, as tourism is an important source of income in Andorra. (3) The direction of the arrow linking pressure tourism (tourism henceforth) to road traffic was changed, as tourism causes road traffic growth and not vice versa. (4) Some of the signs of component number 15 were modified due to the changes explained above. (5) The link between biological agents and air pollutants was removed because of the low levels of air pollutants in the transhumance routes in Andorra.

The final FCM evaluated by the Andorran experts is shown in Figure 4, with 25 components and 56 connections.

Figure 4.

FCM revised for experts in the conservation of Andorran transhumance heritage. The variables were classified into four groups: governance factors (pink), natural hazards (green), anthropogenic factors (orange), and tourism plans and others (yellow). The correlation between concepts is linear. (A) Blue lines indicate positive relationships (an increment in the concept related to the arrow origin increases the concept related to the arrowhead) between components. (B) Red lines represent negative relationships (an increment in the concept related to the origin of the arrow decreases the concept related to the arrowhead) between components.

Table 5 shows the results of the Delphi survey in two rounds. The mean of the responses was recorded for each local expert response. The weight of the relationships was calculated by applying Equation (1), described above, to obtain the weight of each expert’s response for each of the questions posed. This numerical value was then introduced into the FCM as the value of the correlation between different components (Table 6).

Table 5.

Results of the questionnaire sent to the seven Andorran experts and is expressed as the number of responses and the percentage (in brackets) according to the four levels of exposure: very important, important, somewhat important, and unimportant.

Table 6.

Adjacency matrix of FCM with the values obtained from de Delphi method. Strong values are highlighted in grey.

All local experts agreed that there was a strong correlation between the conservation of tangible and intangible heritage and the cataloging from the results of the first round (Table 5). However, documentation processes are the basis for the protection and conservation of cultural heritage [52,53]. Systematic recording and management of information helps to make citizens aware of its importance and fragility. Therefore, the experts considered that the effect of “citizen knowledge and involvement” on “vandalism” is positive.

The experts also considered the relationship between “Legislation” and “Cataloguing” to be of great importance. In Andorra, the law stipulates that the State must “guarantee the conservation, promotion and dissemination of the historical, artistic and cultural heritage” [54]. This inevitably implies the registration and cataloging of all tangible and intangible assets of cultural interests.

Alternatively, the law is an important asset in the fight against impunity, providing guidelines for taking appropriate action and establishing sanctions [53]. For this reason, experts agree that legislation also has a very positive influence on the conservation of cultural heritage. The interviews revealed a distrust of the Andorran Cultural Heritage Law, especially concerning the environmental protection of assets of cultural interest, which was modified in 2014 to favor urban plans. This has an impact on urban development in protected areas that is far below expectations.

Furthermore, the survey showed that urbanization processes have a strong negative impact on cultural heritage, especially tangible heritage. Urbanization, particularly in terms of private housing, has led to changes in land use and has had either a direct or an indirect impact on the character of heritage sites [55]. Its regulation is based on the territorial and urban planning law passed in 2000 [56] by each municipality (“Commune”). As some studies have shown [57], the construction boom has destroyed possible archaeological evidence and posed a major threat to monuments and traditional architecture. In fact, from the modification law passed in 2000, the protection perimeter around an asset of cultural interest was drastically reduced. This does not bode well for the monuments and archaeological transhumance heritage sites and their protection.

Finally, the survey results showed that the questions with the greatest discrepancy were those relating to tourism and population density. Andorra receives about 8.43 million visitors each year, in a country with an area of 468 km2. In 2022, the population was 81,588 and growing [58]. Despite these data, the Andorran experts did not attach the same importance to the causal relationship between the current population density in Andorra and the conservation of the cultural heritage. Similarly, in the case of tourism, the experts interviewed did not have a single opinion. Previous studies, such as those by Troitiño [59] and Loulanski [60], show that it is very difficult to integrate tourism into conservation and sustainable development. This problem is often due to poorly designed policies [61]. The current policies in Andorra point towards a sustainable tourism model that protects, preserves, and enhances its cultural heritage, a challenge in a country that receives an average of 8 million visitors each year [62]. Nevertheless, the truth is that tourism continues to be based mainly on snow, sports, and commercial offers [62,63]. In this context, based on the results, it seems difficult for local experts to establish a positive and unanimous correlation between tourism and heritage conservation.

3.3. Static Analysis

From the results of the static analysis (Table 7) provided by the Mental Modeler, the FCM was characterized by a density of 0.093. This value was calculated by dividing the number of connections (c) by the maximum number of possible connections between N variables (density = c/(N*(N−1)). This indicates that the map was relatively sparse [15,26,32,64]. Furthermore, the static analysis showed that the FCM consisted of eight drivers, three receivers, and fourteen ordinary components, with a complexity of 0.375. Thus, stakeholders perceived the system as having more forcing functions than utility variables [26]. This assessment of the FCM showed that the most influential components of the system were “Tourist itineraries for transhumance”, “Citizen awareness and involvement”, and “Population density”. They had a high centrality value, which was of great importance in the cognitive map [32]. Other central components were “Cataloguing”, “Legislation for conservation”, “Tourism”, and “Vandalism”.

Table 7.

Components were obtained from the FCM with the Mental Modeler tool. Strong concepts are indicated in bold.

The driver components and those with a high ratio of outdegree to indegree, as variables that are less affected by changes in the system, are ideal candidates for manipulating and controlling the dynamics of the system [15,26,33,64]. They are the forcing functions of the system and can have positive or negative effects on other concepts, especially those with a high indegree [33], such as the two main ideas of the map.

Considering the above-mentioned components with a high centrality value, “Citizen awareness and involvement”, “Legislation for conservation”, and “Tourism” demonstrated the highest ratio of outdegree to indegree. “Population density” was a driver component. These variables were chosen to generate possible scenarios to understand the consequences of the conservation of tangible and intangible transhumance heritage by influencing them.

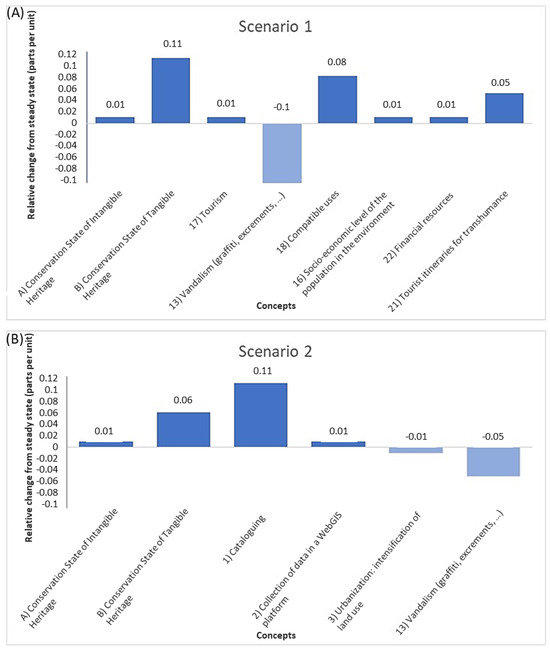

The Mental Modeler scenario interface was used to analyze the four scenarios. Two active policies based on the protection of the transhumance heritage were simulated (Figure 5), through the action of training, awareness-raising, and citizen participation and a fairer, stricter, and more appropriate conservation law. On the other hand, two possible scenarios were simulated in which tourism and the number of people living in Andorra increased (Figure 6). For the first and second scenarios, the components of “Citizen awareness and involvement” and “Legislation for conservation” were given a value of +1 in order to drive the simulation towards a much more protectionist scenario toward transhumance heritage in Andorra (Figure 5). The first scenario showed a significant increase in tourism through guided itineraries and compatible use of the cultural heritage and, consequently, an improvement in the conservation of tangible heritage. Alternatively, vandalism was greatly reduced, and a balance was found between attracting tourists and not damaging heritage. For the second scenario, the result of increasing the value of the concept of “Legislation for conservation” was a scenario in which the strongest point was the decrease in the negative influence of both urbanization and vandalism on tangible heritage. At the same time, cataloging would increase significantly, leading to a slight increase in the conservation of intangible heritage and the collection of data on a WebGIS platform.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of concepts that have a positive impact on the conservation of tangible and intangible transhumant cultural heritage. (A) Scenario 1 demonstrates the positive impact when the population takes part in conservation management. For that, the value of concept number 19 “Citizen awareness and involvement” was increased. (B) Scenario 2 demonstrated the positive impact when governments improve the legislation related to the conservation of cultural heritage and/or transhumance activities. For that, the value of concept number 6 “Legislation for conservation” was increased.

Figure 6.

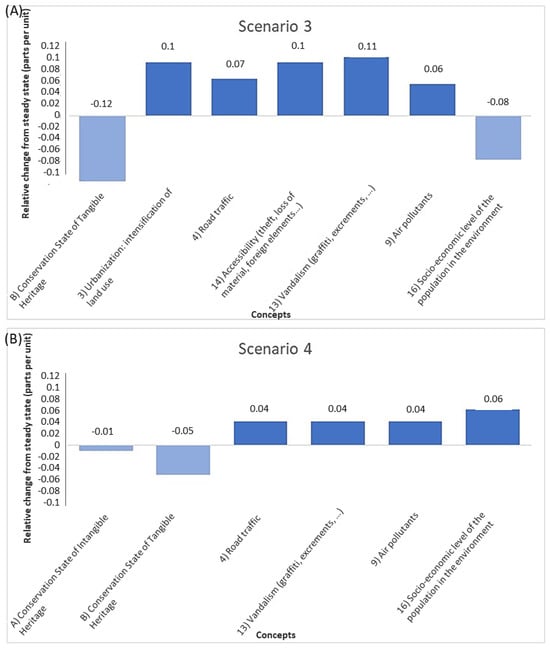

Evaluation of concepts that have a negative impact on the conservation of tangible and intangible transhumant cultural heritage. (A) Scenario 3 demonstrated the influence caused by the increment of demographic pressure. For that, the value of the concept number 15 “Population density” was increased. (B) Scenario 4 demonstrated the influence of the current development of mass tourism. For that, the value of concept number 17 “Tourism” was increased.

For the third and fourth scenarios, the components of “Population density” and “Tourism” were given a value of +1 to understand how they would affect the conservation of cultural heritage in the system if there were an increase in tourism or population (Figure 6).

As the value of component 15 “Population density” increases, the state of conservation of the tangible heritage decreases significantly. This is because the main components that are perceived to have a negative impact on the heritage, such as urbanization, road traffic, accessibility, vandalism, or air pollution, increase significantly.

Similarly, for component 17 “Tourism”, the simulation results for scenario 4 show that the conservation of transhumance heritage would be negatively affected by increasing tourism. In this case, the decrease is less significant than in the previous case; however, it occurs for tangible and intangible heritage. Road traffic, vandalism, and air pollution show a similar increase. The positive data in this simulation are the impact of tourism on the social and economic development of the Andorran population. Undoubtedly, the resources generated by tourism would be returned to the population through investment in culture, education, and health.

Nevertheless, the demographic data and indicators of the population of Andorra and the percentage of tourists visiting the country have remained stable over the last 15 years [65], indicating that Andorra is still far from these two scenarios.

4. Discussion

Preventive conservation is one of the most important strategies to ensure the resilience of cultural heritage [66], as it allows organizations to anticipate possible events. Methodologies based on vulnerability assessment, taking into account both tangible and intangible values, are particularly prevalent when analyzing the conservation of cultural heritage, which depends on multi-hazard assessments in urban, rural, or coastal environments. Multi-scenario studies are required to encompass disaster events and/or changes over time [4,5]. The methodology developed in this research considers the relationship between all the different variables and their influences when making predictions in a complex and dynamic system such as transhumance activity and not just design for a group of buildings [46,67] or isolated monuments [68]. In addition, the use of the FCM allowed modification of the influence of one or more variables in positive or negative cases, studying the changes caused by each variable as well as the whole model [19].

4.1. FCM and Its Improvement by Andorran Experts

The basis of this methodology is the combination of the FCM and Delphi surveys. Currently, it is a common practice to combine different methods to obtain indexes to facilitate predictions about the behavior of cultural heritage, in particular by using indexes such as the Flood Vulnerability Index [6], the Fire Risk Index [7], and the Climate Change Index [8]. These indices attempt to help stakeholders make decisions and set priorities. However, all these indices are usually designed for one or more specific hazards. The developed methodology has provided an overview of a complex system, in this case, the conservation of transhumance cultural heritage. An important advantage observed after its application in the case of Andorra was the possibility of evaluating many different situations or scenarios, such as the implementation of elaborate dynamic strategies, considering both positive and negative scenarios, not only the worst cases. For example, in the Andorran case, this model could be used by the Government of Andorra for the elaboration of the project to include transhumance and its heritage in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, demonstrating the possible benefits of the conservation measures developed and the resilience of the system to possible negative events.

The FCM is a useful tool to depict, explain, take-decisions, or make predictions about systems. Nevertheless, some limitations have been reported about its use and the significance of its results [36]. The main limitations are related to the recruitment of expert panels, the homogeneity in the concept identifications, and the relationships considered between them. Our research design tried to minimize them. First, an interdisciplinary and international expert panel (Table 1) built a preliminary FCM. The number of experts on a panel must be related to the ability of a new expert to define new concepts or relationships. According to Infante-Moro et al. [36], with more than five experts, the number of new concepts or relationships proposed by a new expert decreases significantly. In this case, five experts built the FCM, and a second expert panel (seven experts in Andorran cultural heritage, Table 2) amended it. Landeta [69] explains that two types of experts can be involved in solving a problem, specialists on the issue and those affected by the issue. The use of two panels of experts in the construction of the FCM tried to combine both points of view.

The second panel used the Delphi method. This method has been questioned in terms of aspects related to the concept of an expert, the design of the questionnaires, the authenticity of the consensus achieved by the experts, etc. [70]. Nevertheless, Delphi surveys are an anonymous method that avoids the influence of leaders and allows the initial judgment to be refined based on the panel’s opinions and reflections on their own previous choices [42]. There is no consensus on the optimal panel size for this method [71], and sometimes it is preferable to carefully select a small group on a given topic [72]. In this case, the Delphi method with Andorran experts allowed validation of the FCM built first by an expert panel and then adapted to the country’s specifications. For example, while in most European rural areas depopulation is a major risk for the conservation of transhumance activities and their cultural heritage [73], in Andorra this phenomenon does not exist, and it is not a large problem for Andorran heritage conservation, as indicated by the responses of the Andorran experts (Table 5). It has been verified that this methodology is adaptable to the specificities of the area analyzed and can be easily applied to other regions.

4.2. Implementation of Static and Dynamic Analysis in Planning and Decision–Making

Static analysis allows the identification of the main variables of the FCM. This analysis was based on the centrality value. The highest values of centrality were related to “Population density”, “Legislation for conservation”, and “Tourism”. This is in agreement with recent research about the conservation of Andorran vernacular heritage [74], where the lack of conservation of traditional buildings is linked to the increase in the population and the development of mass tourism, while the Cultural Heritage Act, since 2003, has played a fundamental role in the policy focused on the recovery of vernacular architecture.

After identifying the main concepts, different scenarios analyzed the dynamics of the system in which changing the tendency of some of these variables could allow stakeholders to minimize the impact of the hazards on the conservation of cultural heritage and take advantage of opportunities to generate a resilient system. For example, scenario 4 (Figure 6) showed the consequences of the rise in tourism. Since the 1970s, Andorra has developed a mass tourism model that has had a significant impact on its economy, especially in sectors such as commerce and construction. In this scenario, the increase in tourism led to a rise in pollution and road congestion. The Andorran population, in a recent study, also mentioned these aspects in their perception of the current tourism model and its consequences [62]. In this way, it is observed that the increase in tourism, without improving its model and regulation, leads to mass tourism, which is not sustainable tourism. The sustainable tourism model advocates its development through the conservation of resources and cooperation with the local population [74]. When the local population participates in conservation management (Scenario 1, Figure 5), the conservation of heritage is enhanced, which favors the development of tourism and the compatibility of uses of the heritage, improving local economic development. In this way, the use of the different scenarios allows stakeholders to anticipate certain decisions and their consequences in the medium to long term.

5. Conclusions

The methodology developed in this research is based on the combination of the FCM with the Delphi method to analyze expert perceptions of the factors influencing the conservation of transhumance heritage. The main advantage of this methodology is that it allows the study of worse-case scenarios, which is common in previous research, but also allows the identification of opportunities. In addition, the FCM is a cheap and simple tool to model the individual and collective components that guide the conservation of cultural heritage; so, this methodology is versatile and does not require detailed knowledge for its implementation, as can be seen related to Andorran transhumance.

The combination of the FCM and Delphi surveys adapts the model to the specificities of each region or type of cultural heritage, taking into account the expertise and knowledge of local experts and/or managers. Specifically, in this study, the FCM was reformulated from a general overview of the case by an international panel to the specificities of Andorra. Thus, the FCM is a dynamic modeling tool in which the representation of the system can be easily modified by incorporating new variables and changing their links.

The results regarding the expert understanding of the conservation of the Andorran transhumance heritage have shown that material heritage is perceived to have more influence on the system than immaterial heritage. According to the FCM results, tourism and the political sector are the most relevant and influential factors in the system built by experts. On this basis, four scenarios were run using the Mental Modeler software to develop two hypotheses that contribute to better conservation of transhumance heritage and two other possible hypotheses that could have the opposite effect. For example, a policy based on increasing citizens’ awareness of their level of responsibility will develop more sustainable tourism and improve the conservation of transhumance heritage, or conservation will improve if political commitment correctly implements the existing law and increases the legal protection for transhumance heritage. On the other hand, a sharp increase in tourism and population would make cultural heritage more vulnerable. The results have shown that scenario analysis can be useful for stakeholder decision-making, providing alternatives for better protection and conservation of cultural heritage, and predicting their effects. Therefore, it is a good tool to be used in the development of urban, rural, and landscape planning in all types of contexts, from local to national decisions.

Finally, this study will serve as a basis for new studies in other regions or countries and help in planning and decision-making in the field of preventive conservation and management. For that, future research should focus on the implementation of this model in other transhumance systems and their cultural heritage conservation, such as in Italy, Greece, and Iceland. These countries participated in the PECUS project and their experts took part in the initial formulation of the Andorran FCM (Table 1). Comparing the possible results obtained in each country could help to establish common recommendations for the conservation of transhumance cultural heritage, similar to the documents published by UNESCO [12] or the Spanish Government [75] for intangible heritage conservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and R.O.; methodology, L.S., R.O., J.B. and P.O.; validation, L.S.; formal analysis, L.S., R.O., J.B. and P.O.; investigation, L.S., R.O., J.B. and P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S., R.O., J.B. and P.O.; writing—review and editing, J.B. and P.O.; funding acquisition, P.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the PECUS project, funded by the European Erasmus+ programme under grant [2019-ES01-KA203-065197].

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from article authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would first like to thank the members of the PECUS project, especially those who have been directly involved in the development of the FCM. It would not have been possible without them. We would also like to thank those who took part in the survey: Mireia V., Mireia T., Berna G., David M., Edu T., Lídia T., and Sara U. Finally, we would like to thank David Mas again for his valuable references, which provided us with a literature base for the study of traditional pastoralism and transhumance in Andorra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liechti, K.; Biber, J.P. Pastoralism in Europe: Characteristics and Challenges of Highland-Lowland Transhumance. OIE Rev. Sci. Tech. 2016, 35, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.J. Flood Risk Maps to Cultural Heritage: Measures and Process. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rosales, B.; Abreu, D.; Ortiz, R.; Becerra, J.; Cepero-Acán, A.E.; Vázquez, M.A.; Ortiz, P. Risk and Vulnerability Assessment in Coastal Environments Applied to Heritage Buildings in Havana (Cuba) and Cadiz (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, R.; Ortiz, P.; Martín, J.M.; Vázquez, M.A. A New Approach to the Assessment of Flooding and Dampness Hazards in Cultural Heritage, Applied to the Historic Centre of Seville (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andretta, M.; Coppola, F.; Modelli, A.; Santopuoli, N.; Seccia, L. Proposal for a New Environmental Risk Assessment Methodology in Cultural Heritage Protection. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 23, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.N.; Ferreira, T.M. A Simplified Approach for Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Historic Sites. Nat. Hazards 2019, 96, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.M.; Kaplan, M.E. Fire Risk Index for Historic Buildings. Fire Technol. 2001, 37, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forino, G.; MacKee, J.; von Meding, J. A Proposed Assessment Index for Climate Change-Related Risk for Cultural Heritage Protection in Newcastle (Australia). Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera Millán, M. Organización de Los Espacios de Pastos En La Montaña Atlántica: Los Nombres, Las Formas y Las Funciones. Ería 2013, 93, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Guillot, F. Le Pastoralisme Au Moyen Âge En Vallée Du Vicdessos, à Travers La Documentation Écrite Médiévale: Grands Troupeaux et Communautés Paysannes; 2014. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-00870874/document (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Mas, S. Aspectes de l’art Popular d’Andorra; Impremta Principat: Andorra la Vella, Andorra, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Kosko, B. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Int. J. Man. Mach. Stud. 1986, 24, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, R. Structure of Decision: The Cognitive Maps of Political Elites; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1976; ISBN 9781400871957. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso González, C.; García de Jalón, D.; Solana Gutiérrez, J.; Rincón Sanz, G. Utilización de Mapas de Conocimiento Difuso (MCD) En La Asignación de Prioridades de La Restauración Fluvial: Aplicación al Río Esla. Cuad. Soc. Española Cienc. For. 2015, 41, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, A. Imperfect Causality: Combining Experimentation and Theory. In Combining Experimentation and Theory. Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 271, pp. 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, E.I.; Markinos, A.; Gemptos, T. Application of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps for Cotton Yield Management in Precision Farming. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 12399–12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, E.; Kontogianni, A. Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping in Environmental Decision Making and Management: A Methodological Primer and an Application. In International Perspectives on Global Environmental Change; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.A.; Gray, S.; Cox, L.J.; Henly-Shepard, S. Mental Modeler: A Fuzzy-Logic Cognitive Mapping Modeling Tool for Adaptive Environmental Management. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; pp. 965–973. [Google Scholar]

- Henly-Shepard, S.; Gray, S.A.; Cox, L.J. The Use of Participatory Modeling to Promote Social Learning and Facilitate Community Disaster Planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 45, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Stewart, A. Sustainable Forestry Decisions: On the Interface between Technology and Participation. Math. Comput. For. Nat.-Resour. Sci. 2011, 3, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, P.; Blanco, M.; Castro-Campos, B. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: A Fuzzy-Cognitive Mapping Approach to Support Nexus-Compliant Policies in Andalusia (Spain). Water 2018, 10, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, B.F.; Ludsin, S.A.; Knight, R.L.; Ryan, P.A.; Biberhofer, J.; Ciborowski, J.J.H. Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping as a Tool to Define Management Objectives for Complex Ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 2002, 12, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, M.-A.; Coculescu, C. Modeling Of Urban Policies For Housing With Fuzzy Cognitive Map Methodology. J. Inf. Syst. Oper. Manag. 2015, 9, 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, E.I.; Salmeron, J.L. A Review of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps Research during the Last Decade. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2013, 21, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özesmi, U.; Özesmi, S.L. Ecological Models Based on People’s Knowledge: A Multi-Step Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping Approach. Ecol. Modell. 2004, 176, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, J.L.; Vidal, R.; Mena, A. Ranking Fuzzy Cognitive Map Based Scenarios with TOPSIS. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Chan, A.; Clark, D.; Jordan, R. Modeling the Integration of Stakeholder Knowledge in Social-Ecological Decision-Making: Benefits and Limitations to Knowledge Diversity. Ecol. Modell. 2012, 229, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, W.; Kurgan, L.; Pedrycz, W.; Reformat, M. Genetic Learning of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2005, 153, 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.A.; Gray, S.; de Kok, J.L.; Helfgott, A.E.R.; O’Dwyer, B.; Jordan, R.; Nyaki, A. Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping as a Participatory Approach to Analyze Change, Preferred States, and Perceived Resilience of Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, J.L. Supporting Decision Makers with Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2009, 52, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özesmi, U.; Özesmi, S. A Participatory Approach to Ecosystem Conservation: Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Stakeholder Group Analysis in Uluabat Lake, Turkey. Environ. Manag. 2003, 31, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia de Jalón, D.; Alonso, C.; González del Tango, M.; Martinez, V.; Gurnell, A.; Lorenz, S.; Wolter, C.; Rinaldi, M.; Belletti, B.; Mosselman, E.; et al. Review on Effects of Pressures on Hydromorphological Variables and Ecologically Relevant Processes|REFORM. Available online: https://www.reformrivers.eu/deliverables/d1-2 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Santoro, S.; Pluchinotta, I.; Pagano, A.; Pengal, P.; Cokan, B.; Giordano, R. Assessing Stakeholders’ Risk Perception to Promote Nature Based Solutions as Flood Protection Strategies: The Case of the Glinščica River (Slovenia). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.A.; Zanre, E.; Gray, S.R.J. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps as Representations of Mental Models and Group Beliefs. Intell. Syst. Ref. Libr. 2014, 54, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante-Moro, A.; Infante-Moro, J.C.; Gallardo-Pérez, J. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Their Application in Social Science Research: A Study of Their Main Problems. Educ. Knowl. Soc. (EKS) 2021, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuero, A.G.; Sayago, A.; González, A.G. The Correlation Coefficient: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2006, 36, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: An Efficient Procedure to Generate Knowledge; Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 0-201-04294-0. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J. Current Validity of the Delphi Method in Social Sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguant-Álvarez, M.; Torrado-Fonseca, M. El Método Delphi. REIRE Rev. d’Innovació Recer. Educ. 2016, 9, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Ortiz, P. Vulnerability Index: A New Approach for Preventive Conservation of Monuments. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2016, 10, 1078–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, P.; Antunez, V.; Martín, J.M.; Ortiz, R.; Vázquez, M.A.; Galán, E. Approach to Environmental Risk Analysis for the Main Monuments in a Historical City. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Ortiz, P.; Vázquez, M.A.; Martín, J.M. Integration of Georeferenced Informed System and Digital Image Analysis to Asses the Effect of Cars Pollution on Historical Buildings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 1, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, A.J.; Turbay, I.; Ortiz, R.; Chávez, M.J.; Macías-Bernal, J.M.; Ortiz, P. A Fuzzy Logic Approach to Preventive Conservation of Cultural Heritage Churches in Popayán, Colombia. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2020, 15, 1910–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, J.L. Estrategias de Ponderación de La Respuesta En Encuestas de Satisfacción de Usuarios de Servicios. Metodol. Encuestas 2002, 4, 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, R.B.; González, S.; Maikel, E.; Leyva Vázquez, Y. Análisis Estático En Mapas Cognitivos Difusos Basado En Una Medida de Centralidad Compuesta. Cienc. Inf. 2014, 45, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Maridueña Arroyave, M.R.; Leyva Vázquez, M.; Febles Estrada, A. Modeling and Analysis of Science and Technology Indicators Using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Inf. Sci. 2016, 47, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache, F.; Leyva Vázquez, M. Modelos Mentales y Mapas Cognitivos Neutrosóficos. In Neutrosofía: Nuevos Avances en el Tratamiento de la Incertidumbre; Pons Publishing House: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 34–43. ISBN 9781599735726. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla Espino, D.; Jiménez de Madariaga, C. Modelado Del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial de La UNESCO Mediante Mapas Cognitivos Difusos. In Annals of Applied Economics (ASEPELT 2017); Mendes, I., Borges, M.R., Coelho, M., Mendes, Z., Eds.; SOCIUS/ISEG and ASEPELT: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017; pp. 226–239. ISBN 978-989-96593-5-3. [Google Scholar]

- Masciotta, M.G.; Morais, M.J.; Ramos, L.F.; Oliveira, D.V.; Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; González-Aguilera, D. A Digital-Based Integrated Methodology for the Preventive Conservation of Cultural Heritage: The Experience of HeritageCare Project. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 15, 844–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, G.; Thompson, J.; Young, C. Managing Cultural World Heritage; UNESCO, ICOMOS, ICCROM, IUCN: Paris, France, 2013; ISBN 978-92-3-001223-6. [Google Scholar]

- Consell General del Principat d’Andorra. Llei 9/2003, Del 12 de Juny, Del Patrimoni Cultural d’Andorra. In Butlletí Of. Principat D’andorra; 2003; 55, pp. 1887–1897. [Google Scholar]

- Agapiou, A.; Alexakis, D.D.; Lysandrou, V.; Sarris, A.; Cuca, B.; Themistocleous, K.; Hadjimitsis, D.G. Impact of Urban Sprawl to Cultural Heritage Monuments: The Case Study of Paphos Area in Cyprus. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consell General of the Principality of Andorra. Llei General. d’ordenació Del. Territori i Urbanisme. In Butlletí Of. Principat D’andorra; 2021; 10, pp. 379–400. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Houdalieh, S.H.; Sauders, R.R. Building Destruction: The Consequences of Rising Urbanization on Cultural Heritage in the Ramallah Province. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2009, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departament d’Estadística (Govern d’Andorra). A179. Economic Overview, 2022; Govern d’Andorra: Andorra, 2023. Available online: https://www.estadistica.ad/portal/apps/sites/#/estadistica-ca/pages/publicacio?Idioma=ca&Id=31107&IdCat=3 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.Á.; Troitiño Torralba, L. Territorial View of Heritage and Tourism Sustainability. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2018, 78, 212–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loulanski, T.; Loulanski, V. The Sustainable Integration of Cultural Heritage and Tourism: A Meta-Study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 837–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor Alfonso, M.J. El Patrimonio Cultural Como Opción Turística. Horiz. Antropológicos 2003, 9, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Garcia-Lluelles, E.; Valiente, G.C.; Casalprim-Ramonet, M. El Impacto Del Turismo En Andorra: La Percepción De Los Residentes. Cuad. Tur. 2023, 52, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, T.; Berthet, N. Andorra, Contexto Presente Del Turismo Nodal Entre Francia y España. Eur. Sci. J. 2012, 8, 78–101. [Google Scholar]

- Christoforou, A.; Andreou, A.S. A Framework for Static and Dynamic Analysis of Multi-Layer Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Neurocomputing 2017, 232, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govern D’Andorra Institut d’Estudis Andorrans. Available online: https://www.iea.ad/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Holtorf, C. Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience Is Increased through Cultural Heritage. World Archaeol. 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, A.J.; Macías-Bernal, J.M.; Chávez de Diego, M.J.; Alejandre, F.J. Expert System for Predicting Buildings Service Life under ISO 31000 Standard. Application in Architectural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 18, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herráez, J.A.; Durán, D.; García Martínez, E. Fundamentos de Conservación Preventiva; IPCE: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Landeta Rodríguez, J. El Método Delphi: Una Técnica de Previsión Para La Incertidumbre; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sackman, H. Delphi Assessment: Expert Opinion, Forecasting, and Group Process; The Rand Corporation: Santa Mónica, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Drumm, S.; Bradley, C.; Moriarty, F. ‘More of an Art than a Science’? The Development, Design and Mechanics of the Delphi Technique. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 2230–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, R. The Delphi Method: A Powerful Tool for Strategic Management. Int. J. Police Strateg. Manag. 2002, 25, 1363–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, J.M.; Tomás-Faci, G.; Diarte-Blasco, P.; Montes, L.; Domingo, R.; Sebastián, M.; Lasanta, T.; González-Sampériz, P.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Arnáez, J.; et al. Transhumance and Long-Term Deforestation in the Subalpine Belt of the Central Spanish Pyrenees: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Catena 2020, 195, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmé Bejarano, E. Preserving Vernacular Architecture in Andorra. Loggia Arquit. Restauración 2020, 33, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. National Plan To Safeguard Intangible Cultural Heritage; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2011. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/planes-nacionales/en/dam/jcr:73de51a5-978f-47c4-a67a-42b20e09fe41/08-inmaterial-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).