3. Design of Evaluation Methodology

During the design phase of the evaluation process, we surveyed assessment methods in the fields of XR-based experiences ranging from XR-specific and museum-related methods to more generic assessment approaches. One example of a generic method that, nevertheless, is used for XR museum experience evaluations [

9,

15] is the System Usability Scale/SUS [

21], not to be confused with the Slater–Usoh–Steed Questionnaire (whose acronym is also SUS) and was developed by Usoh et al. [

22]; both approaches are presented below in this section. Moreover, we surveyed XR-specific UX questionnaires that nevertheless gravitated towards immersive or fully immersive experiences; hence, they were deemed incongruent with the scope of the specific evaluation. Such methods include the Presence Questionnaire developed by Witmer and Singer [

23]. The sense of presence is a key element for Virtual Environments (VE). Lee [

24] ‘tentatively’ defines it as “a psychological state in which the virtuality of experience is unnoticed”, or, according to Witmer and Singer [

23], it is the subjective experience of being in one place or environment, even when one is physically situated in another. However, in the case of an AR application such as that used in the Tomato Industrial Museum exhibition, measuring the participants’ sense of presence is not appropriate as it concerns VR experiences. We, nevertheless, include an outline of the main methodologies in the wider field of evaluating XR applications and, consequently, delineate the reasoning behind the method chosen in this study.

We opted to base our approach on the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ), which was developed by Laugwitz et al. [

25] and is presented in detail below in this section. Returning to the main methodologies used in assessing XR apps, Schwind et al. [

26] identified that Witmer and Singer [

21] are by far the most cited authors that present a questionnaire on Presence in XR environments. Likewise, Grassini and Laumann [

27], who provide a thorough Systematic Review of published research measuring presence, surveyed 20 papers and, according to their findings, Witmer and Singer’s Presence Questionnaires (PQ) are used more frequently than any other measuring approach.

Grassini and Laumann [

27] offer a comprehensive outline of the issues and trends related to researchers’ efforts to measure presence in XR environments: The PQ questionnaire emphasizes the “involvement” and “immersion” characteristics of the simulated environment, while the Slater–Usoh–Steed Questionnaire (SUS) and the Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ) [

28] are focused on the sense of “being there” (i.e., the sense that the experienced VE may be part of the reality). The MEC-SPQ questionnaire [

29] analyzes what is called “spatial presence”. Moreover, although MPS (Multimodal Presence Scale) [

30] offers some very interesting aspects, it is hinged on spatial attributes and parameters of the experience in VE, as well as on one’s own sense of body/avatar as ‘real’ in a VE. Furthermore, social presence is vital in MPS, but this follows Lee’s [

24] conceptualization of presence in VEs.

Another widely cited and used approach in XR-related experiences is that of the Slater–Usoh–Steed Questionnaire (SUS) developed by Usoh et al. [

22]. This approach, according to [

22], was developed over several studies by Slater and colleagues and most recently used in Slater et al. [

31]. This questionnaire is based on several questions that are all variations on one of three themes: the sense of being in the VE, the extent to which the VE becomes the dominant reality, and the extent to which the VE is remembered as a ‘place’. As this questionnaire focuses on the sense of space, it is deemed less helpful for our study. The System Usability Scale (also described by the acronym SUS) [

21] is often used as the core component in the questionnaires employed in assessing user experience in virtual museum applications, both online and in situ (within an actual museum).

What transpires at this point is that while there is a profusion of quantitative evaluation methods specifically developed to capture aspects of the user experience in an immersive VE, there is a caveat about questionnaires that are designed to assess the complex interrelation of augmented reality apps within physical galleries and used in tandem with actual artefacts/exhibitions.

As mentioned above, the core method employed in the evaluation process is the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) developed by Laugwitz et al. [

25], which is a thorough, yet relatively succinct, questionnaire that uses a 7-step Likert Scale and measures User Experience (UX) in relation to interactive digital interfaces. UEQ captures both objective and subjective aspects of user experience and can streamline the analysis process given that it embeds specifically developed benchmarks and several checks and balances to avoid (statistical) inconsistencies by filtering out not-dependable response patterns through a complex mechanism. Compared to most of the pertinent questionnaires, its distinctive characteristic is that it measures user experience based on different scales that correspond to specific areas of interest, thus allowing for more focused insights to be gained. The UEQ comprises 26 questions, divided into six (6) scales as follows:

Attractiveness;

Efficiency;

Perspicuity;

Dependability;

Stimulation;

Innovation.

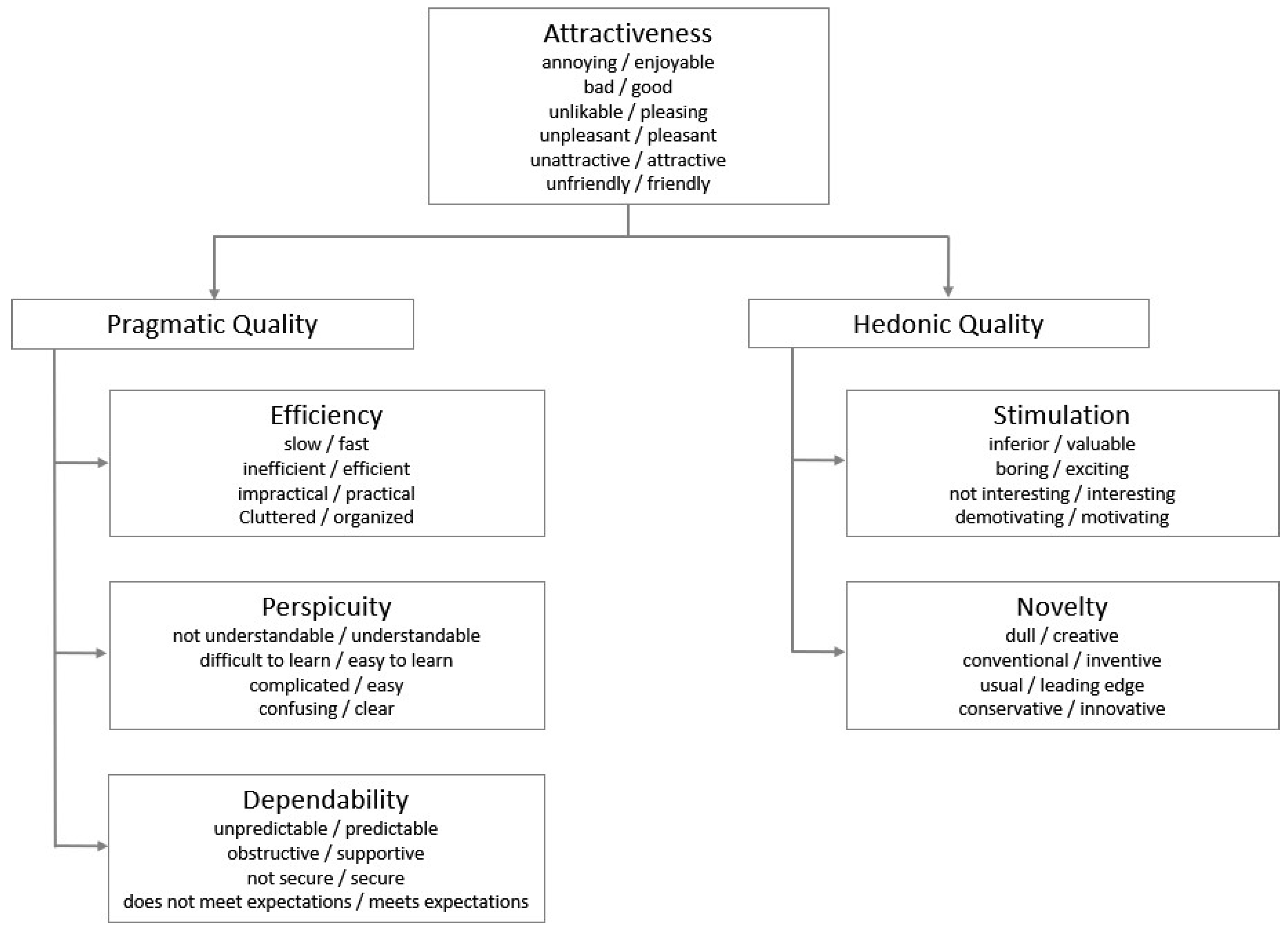

These scales belong to two broader fields: the first field concerns pragmatic or practical qualities (pragmatic qualities), which are related to efficiency (ease of use), perspicuity, which, in fact, relates to the ease of getting used to the system, and dependability (degree of control). These, in broad terms, could be seen as objective aspects of the assessed application. The second field concerns the so-called hedonic qualities. These, by and large, subjective qualities include the scale of stimulation, i.e., how exciting and motivating the use of the application is, and that of innovation, which concerns how creative, inventive, and innovative the digital interaction environment is. The two broad areas of pragmatic and subjective/hedonic qualities (the latter related to the satisfaction offered by an interactive environment) affect the overall degree of attractiveness, i.e., (a) the overall impression it leaves and (b) how much it is liked by users (attractiveness scale), which is mainly about how creative, inventive, and innovative the digital interaction environment is.

The creators of UEQ freely offer at the site manuals, related questionnaires, and spreadsheets for data analysis. In these spreadsheets, the response data input automatically produces results in relation to how the resulting average values are characterized (excellent, good, above or below average, and poor) for each scale based on special benchmarks that the researchers have developed [

32]. This flexible method can be applied in different evaluation scenarios [

33] and was seen as very appropriate and useful for the specific evaluation process described in this paper, given the existence of special benchmarks according to the area of use.

A key strength of this method, apart from the fact that it distinguishes and incorporates pragmatic and so-called hedonic qualities (

Figure 1), which are both crucial factors, especially for a heritage-related museum environment, is that UEQ automatically produces, as mentioned, a description of the ensuing results (based on benchmarks that accrue from hundreds of cases of UEQ employment). This will add to the validity and accuracy of the second phase results. The following figure (adapted from the UEQ handbook) provides an overview of the correspondence between scales and questions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Apparatus and Visual Content

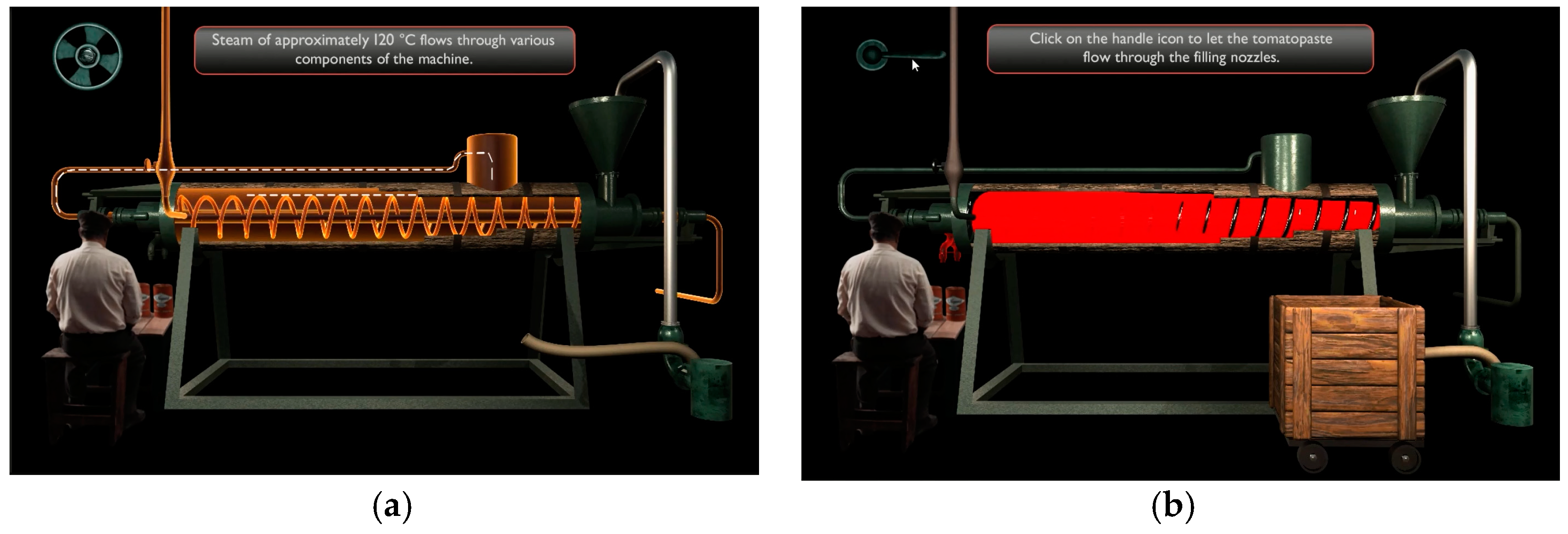

The process is rendered with a mixture of actual humans dressed as workers who were correlated with digitally produced representations of the specific machine, which could be described as follows: tomato juice boils in the cauldron (bolla) under a vacuum to condense and become a pulp (

Figure 2). When the process is complete, the worker opens a valve, and the pellet falls into a cart below, as shown in the illustration below (

Figure 2).

The focus of the evaluated AR application is on illustrating how the pasteurization-filling machine works, making visible its “invisible” parts. Moreover, the correlation between the natural museum environment and the virtual environment of the application was carried out so that the virtual representation of the pasteurization machine was juxtaposed with the real one in the exhibition space. The AR app is on a pad/tablet mounted on a stable base in front of the specific exhibit.

The following objectives were set for the implementation of the application concerning the thermal filling machine:

- (a)

Basic overview of the elements that comprise the machine;

- (b)

Indicative representation of the operation of the machine in successive stages;

- (c)

Creation of an engaging scenario that motivates the user and indicates the essential required functions without complicating them with a large amount of mechanical information;

- (d)

Configuring an easy-to-use and, at the same time, entertaining control interface;

- (e)

Enrichment with moving elements and sound effects that arouse interest and facilitate the understanding of the subject.

The following two screenshots (

Figure 3) present various stages of the AR application with which visitors interact (for a detailed account of the AR app integration in this exhibition, see Sylaiou et al. 2023 [

34]). The black background in the actual imagery seen by users on site is ‘filled’ by the actual surroundings of the exhibits in the museum space.

It is a sequential, task-orientated, and interactive application that involves indicative sounds and movement that introduce the machine’s primary function. An additional element that is envisaged to add to the affective potential and the technologies’ ability to engage visitors is the addition of narrations with the use of audio guides, bringing to life aspects of how it was to work in this industry.

Moreover, narrations, as well as AR visualizations of the production line and workers’ duties, are based on a mixture of different technologies, devices, and degrees of interactivity as if they form an analogy to the differing stages of labor in the factory, which correspond to specific types and conditions of work.

4.2. Participants

One hundred and twenty-one (121) participants filled out the User Experience Questionnaires (UEQ) described above after their visit to the D. Nomikos Museum. They were from both Greece and abroad, and there was a gender balance amongst the respondents as the numbers were almost equal (63 men, 58 women). Participants were, for the most part, tourists, mainly from Europe and the US, as the evaluation took place within the summer period. Moreover, five (5) interviews took place with thirteen (13) responders (three pairs, one group of three people, and one of four). Gender balance was observed in this case as well, and the participants were seven (7) men and six (6) women, mainly from abroad (eleven tourists/foreigners and two Greeks). Interviewees, for the most part, declared that they had prior experience in pertinent XR applications (e.g., in culture/heritage sites).

4.3. Experimental Procedure

The participants were informed about the evaluation process/research and were kindly invited to participate. They were handed the UEQs immediately after completing their museum visit, which included a combination of the audio tour and, most importantly, XR application on tablets that were mounted on tripods in front of the most salient exhibit (selected machine that was the most prominent and crucial in the production line).

Participants that agreed to be interviewed after being informed about the assessment procedure were guided to a specific space where the semi-structured interviews were held. They were asked about their overall experience in the museum, as well as encouraged to make comments about possible ways to improve aspects of the design of the exhibition with emphasis on the employment of XR technology. Lastly, interviewees were asked about their prior experience in pertinent applications, especially in similar settings. The interviews lasted about seven to twelve minutes, depending on the number of responders as well as the length of the answers.

5. Results

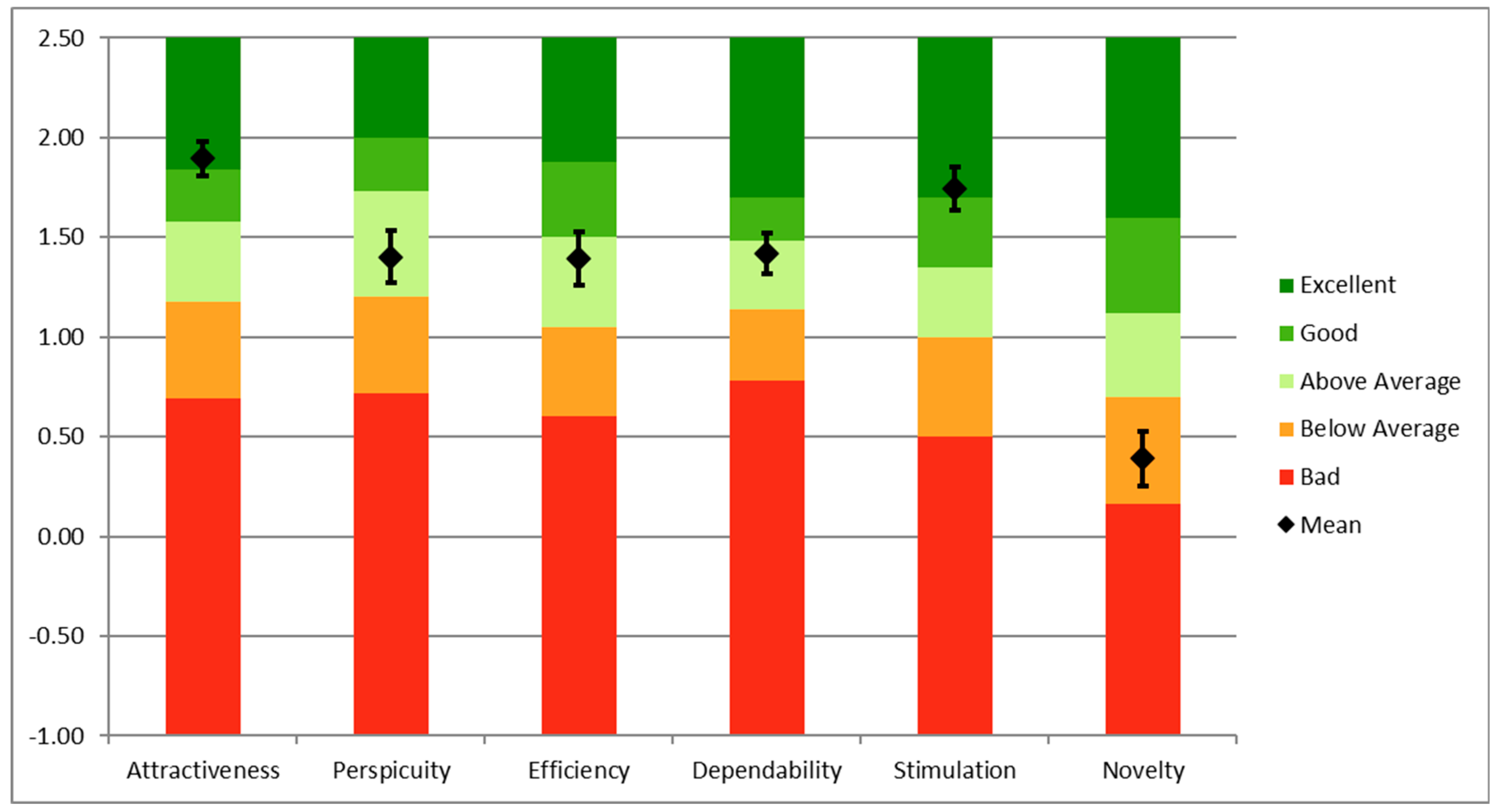

The findings, as the chart below illustrates, offer an overview of the actual results from a number of hundred twenty-one (121) participants in relation to given benchmarks (created by UEQ developers on the basis of a large number of studies that employed this tool). The initial findings indicate that overall attractiveness and stimulation were (marginally) above the ‘excellent’ benchmark, and perspicuity, efficiency and dependability (the three constituent scales of the pragmatic qualities) were well above average, while the novelty scale was, conversely, well below the average mark (

Figure 4).

What can be seen immediately is that while the evaluation showed that the application(s) embedded in the exhibition were positively accepted in relation to their attractiveness and ability to stimulate, the pragmatic qualities (i.e., perspicuity, efficiency, dependability) faired reasonably well, and above average. At the same time, the scale of innovation received a below-average assessment. In other words, attractiveness, which is seen as the most salient and important metric, received excellent evaluation responses; the pragmatic aspect went very well, whereas the hedonic qualities appear to receive (and yield) widely diverging results. Hedonic qualities, which are quite key for a culture/heritage-related user experience, appear to split into a very high acceptance in relation to stimulation and mediocre results in relation to novelty/innovation.

Upon closer inspection, the scale of novelty/innovation is comprised of a set of four questions (in fact, pairs of opposites) that dictate the overall result (shown in the graph/chart below in gold-ochre color). One immediately notices that the very last of the questions (and one of four constitutive questions for the specific scale) yielded considerably (and to an extent surprisingly) negative results. This is the only question from the entire questionnaire in which responders (heavily) gravitated toward the opposing end of the spectrum (

Figure 5).

While the fact that another question (in the middle part of the chart), namely the one regarding ‘conventional/inventive’ binary opposites, is towards the middle point (and thus contributes to the overall mediocre level of the evaluation in relation to this scale), corroborating the rather low acceptance of the application(s) in this respect, another two questions yielded positive responses, although they regarded fairly similar aspects. We investigated possible statistical inconsistencies and thereby filtered out about 10 percent of the responses in accordance with the proposed guidelines, but the results remained virtually the same (thus, we deemed it unnecessary to add these charts as well as they would clutter the article with unwarranted visuals/charts that diverge insignificantly.

Findings from Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviewees were asked to share their opinion on whether the integration of AR made them enjoy the museum visit more and which aspects of the application they found more engaging. Responders gave a very positive image of the inclusion of AR alongside the exhibits and explained that they found this addition quite stimulating (something reflected in the UEQ results as well). Conversely, participants were asked about what impeded (or could increase) their enjoyment in relation to the AR integration in the museum. They often mentioned that they would like to see more tablets, covering a wide range of exhibits, and an increased degree of interactivity.

The interviews were illuminating as the five sets of responders (in pairs or small groups of three or four) underlined the positive impact of a combination of augmented reality, narratives, and resources provided, which all jointly elevated the perceived experience and degree of engagement. One common theme was the mention of interactivity and enhancement of the experience through fostering understanding of factual procedure-related elements of the production line and corresponding machines, as well as the increased empathy with a rural community that was closely knitted with the local factory (mainly through the embedded narratives). So, the positive impact on visitors’ engagement pivoted around the enhanced ability to relate to the human factor and the workers, and on the other hand, the increased accessibility of the otherwise alien and strange machinery exhibited by visualizing the internal processing functions that are not possible to perceive without multimodal resources that support visitors so that they can grasp what the exhibits’ role was in the manufacturing process. Several comments about possible improvements gravitated around an increase in the number of machines covered by the Augmented Reality application, and enhanced, more interactive visualization of additional processes so that a more comprehensive understanding of the procedure could be gained.

Moreover, the issues of rendering more aptly the scale of business, intensity, and volume of the labor as well as actual produce were deemed as an area for improvement. An interview raised the issue of visitor guidance, suggesting, e.g., special markings on the floor that may improve visitors orientation and position. Therefore, the responders, who mostly had considerable prior experience from pertinent museum applications, were overall positive about the employment of technologies in the specific exhibition, and the improvements had more to do with amplifying what they deemed a rather reticent employment of applications/digital resources. This, in conjunction with the UEQ results, appears to suggest that a bolder approach, both in terms of scope and scale as well as content and representational conventions, would further foster the user experience and the ability of the museum to engage meaningfully an increasingly demanding and new media-savvy audience.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion of Research Methodology and Findings Analysis

UEQ, which has been chosen as a tool due to its strengths, mainly related to its dependability, benchmarks, ease of analysis, and differentiation between pragmatic and hedonic factors, nevertheless has its limitations for cultural heritage exhibitions as it is not tailored for them. However, highly important factors such as the degree of enjoyment are present within the hedonic qualities. Enjoyment, in particular, is a key parameter in XR evaluation approaches employed by researchers [

35,

36,

37], who include it as a major criterion. In the findings, the application of AR has been characterized as enjoyable and, in fact, received the most positive score amongst the assessed factors (pairs of opposite statements). Enjoyment is deemed an indispensable aspect of a museum visit in a highly influential publication [

38] that presents a model for evaluating the impact of a museum visit that stipulates the Generic Learning Outcomes (GLOs) that describe the areas in which visitors should benefit from the experience of an exhibition.

The hedonic aspects (e.g., engagement) were also addressed during interviews in the current study. However, for museum experiences, there is scope to bridge the gap between methods such as the UEQ with museum-specific questionnaires (e.g., the IMES as outlined in Gong et al. [

12]) so that analysis becomes more streamlined and, at the same time, the areas covered are more apposite for evaluating the museum visitor experience in relation to XR technologies. For example, the knowledge gained or the learnability aspect of the application may not be captured/investigated as such through the UEQ tool, and for this facet, we relied on interviews to gather data. The answers revealed a considerable impact on learning through increased engagement due to the appeal of the digital resources available at the exhibitions. Especially in a culture-related or even more in an art exhibition, additional fine-tuning of existing questionnaires is needed to cover issues of meaningful engagement with exhibits while maintaining the practicality of the UEQ analysis/benchmark provisions.

6.2. Discussion of Findings and Concluding Remarks

AR and the use of digital narratives, as this study shows, can significantly enhance the museum experience given that, in the case of the specific exhibition, audience commitment has been fostered because of the technology inclusion, and visitors were more actively and emotionally involved. For example, the ability of the visitor to gain insights on ‘how life was back then’ through the narrations of virtual people representing workers has been described as fascinating as it allows users to connect with the historical, social, and cultural context regarding the community that was inextricably linked to the factory. The apps also foregrounded the relationship between local community and the tomato factory, and this was deemed highly interesting. Narrations helped responders to relate to the era and the people through the combination of narrations and visualizations and this was deemed, apart from being informative, as something that made the experience more ‘human’ and ‘warm’. AR fostered visitors’ engagement as it brought the exhibits to life, enabling them to understand how they functioned by rendering visible the inside of machines, so the users did not have to rely on their imagination. The ability to focus on the physical objects while AR provided audio-visual resources that presented their function fostered the museum experience significantly, and as one responder pointed out, this relates to the fact that nowadays, people rely on visuals to get information, and therefore the apps enhance their engagement with the exhibition.

A salient finding, nevertheless, is that most responders deemed the employment of application(s) conservative rather than innovative according to their selection in the provided Likert scale. This may be regarded not as an indictment in relation to the technology or the format of the application (as backward) but rather as a sense that the actual content of the somewhat repetitive visuals and the rendering of the human actors and machinery function were rather conservative in their approach, perhaps not offering any novel representational visualization and remaining in the safe zone of a generic and conventional depiction. This reading of the finding is bolstered by the abovementioned ‘conventional/inventive’, which gave mediocre results not unlike the ‘unpredictable/predictable’ pair that, although it belongs to a different scale and regards the dependability (e.g., user friendliness) of the system, could well be interpreted by responders as a question that relates to the overall feel of the application in terms of how surprising it may be judged from the discrepancy with the other three questions of the specific scale.

The greatest anomaly in terms of the results is, in fact, the coexistence of excellent responses in terms of attractiveness and stimulation that are not exceptionally bolstered by the pragmatic, useability-related underpinnings of the application(s), at the same time that novelty was deemed leaving a lot to be desired, at the first look. The overall positive reception of the exhibition museological design and concept behind the integration of XR could have benefited if more groundbreaking or at least daring approaches had been adopted, but as said, the broad picture is one of a very good reception. The findings indicate that in the era of new technological innovations, to be truly a step ahead necessitates risk-taking and the adoption of a more unconventional approach in relation to the contents and representational conventions in the multimodal resources that frame and foster user experience in museums today and in the foreseeable future.

In terms of recommendations for future practice, the evaluation process presented in this paper identifies two main areas: the role of the XR in an exhibition and, secondly, the methodology of assessing the impact of such technologies on audience commitment. Firstly, XR should focus on the human factor as much as possible, i.e., provide context about the (exhibition-related) people and their lives, given that virtually every exhibition has a connection to a social environment. This helps bring to life an era or a thematic area by enabling visitors to make a more personal connection and emotionally relate to the represented people and their lives. Digital narratives can play a significant role when used in conjunction with pertinent visualizations, e.g., of workers’ appearance, but also of exhibits’ internal functions, something that is key for industrial museums given the complex nature of exhibits. AR, in particular, can amplify audience engagement as it allows users to stay focused on artefacts while enjoying multimodal digital resources, which bring to life both the exhibits’ qualities and the people related to them.

Last but not least, this evaluation-related paper shows that there is ample scope in developing more specific questionnaire-based methods that can evaluate in a more nuanced way the intricacies of combining Augmented/eXtended Reality with physical exhibits in cultural sites, something that can inspire future research. While the potential for audience engagement with the incorporation of XR becomes evident, in order to capture the nuances of visitors’ emotional and active participation, questionnaires should combine the efficiency of UEQ in translating data into meaningful findings with the use of appropriate benchmarks with the specificity of questionnaires (such as presence questionnaires) that are especially configured to evaluate the user experience of XR museum applications. This combination requires a large body of work in order to gather a critical mass of findings (i.e., many uses of a specially developed questionnaire) and generate the benchmarks underpinning an XR museum equivalent of the UEQ. To fully exploit emerging technologies in industrial museums, a more comprehensive evaluation approach could be based on creating a dependable and pertinent method and establishing metric-related benchmarks that can, in turn, facilitate researchers to improve and streamline their assessment of audience commitment in XR industrial museum experiences, and thereby amplify their efficacy in the future.