Abstract

This study emphasises the pivotal role of emotions and cultural backgrounds in shaping tourists’ perceptions of authenticity within Andalusian Paradores. By employing an innovative machine learning method to analyse an extensive database of User-Generated Content, this research study reveals that certain emotions significantly diminish perceived authenticity. It also demonstrates that cultural and gender differences markedly influence authenticity perceptions. Notably, domestic tourists apply more stringent criteria for authenticity compared with international visitors, who may rely on idealised representations of Spanish culture. SHAP analysis further elucidates the contribution of various characteristics to authenticity perceptions, highlighting the predominance of emotional responses over demographic factors. These insights provide valuable guidance for tourism managers seeking to enhance visitor satisfaction. The findings advocate for the development of nuanced marketing strategies that cater to both international and domestic tourists, thereby fostering deeper engagement with cultural heritage and supporting the long-term sustainability of Andalusian Paradores.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a key sector of the economy, accounting for 3% of the global GDP, and in 2023, it facilitated the movement of 1.286 billion international tourists, with 54.5% travelling to Europe, generating an estimated gross impact of USD 1.3 trillion [1]. Notably, in Europe, and specifically in Spain, the tourism sector has been shaped by a long historical and cultural tradition influenced by various world civilisations. Coupled with the natural and geographical features of its territory, this has made this Mediterranean country the most visited destination in the world in 2023, with over 85.06 million foreign travellers [2] and revenues amounting to EUR 108.662 billion [3]. Spain’s long-standing tourism trajectory has been accompanied by the development of a unique network of state-run accommodations, the Paradores de Turismo, defined by Fernández-Fuster [4] as those complete hotel establishments with all the services required for modern comfort, located at sites of undeniable tourist interest or situated in areas notable for monumental or sporting excursions.

At the beginning of the 20th century, tourism was already emerging as a driver of development in Spain that needed to be promoted. In response to the lack of accommodations catering to high-level social and economic tourism, the Spanish State, starting in 1928 with the creation of the National Tourism Board (Patronato Nacional de Turismo, PNT) and the official establishment during the latter part of the reign of Alfonso XIII, created the Network of State Accommodations. This network comprised a diversified range of distinctly categorised tourist establishments: Paradores, Hosterías (restaurants), Roadside Inns, and Mountain Refuges.

From 1953 onwards, agreements with the United States and Spain’s entry into international organisations marked a new phase in Francoism [5,6,7]. Starting in 1962, the Ministry of Information and Tourism became one of the main drivers of the so-called “Spanish economic miracle” [5] through the Economic and Social Development Plan, initiating the so-called “prodigious decade of the Paradores” [6], which saw the greatest growth in their history, exceeding 70 establishments in the 1960s.

The Spanish region with the highest concentration of Paradores is Andalucía, a territory that received 12.2 million international tourists in 2023 [3], with an estimated economic impact of EUR 884 million [8], making it one of the main tourism drivers of the Iberian Peninsula, only surpassed by Catalonia. Most of the Andalusian Paradores are situated in unique locations of exceptional value, both for their historical significance and their locations in protected natural areas.

In these highly attractive tourist spots are the Paradores of Gibralfaro (1948), Cazorla (1965), Jaén (1965), Arcos de la Frontera (1966), Mojácar (1966), and Carmona (1976). Additionally, the Paradores of Úbeda (1930), Granada (1954), Córdoba (1960), and Mazagón (1968) are situated near UNESCO World Heritage sites (see Figure 1). The Andalusian network is further completed by modern constructions, including the Paradores of Antequera (1940), Málaga (1956), Nerja (1965), Ayamonte (1966), Ronda (1994), and the reconstruction of Hotel Atlántico de Cádiz (2012), for a total of 16 hotel establishments.

Figure 1.

Example of Andalusian Paradores. Andalusian Paradores in the images, in order: (1) Ronda, (2) Úbeda, (3) Granada, (4) Carmona, (5) Arcos de la Frontera, and (6) Jaén. Source: Official website: https://paradores.es/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

Following an introduction that addresses the importance of tourism, the concept, and a brief history of Spanish Paradores, this study continues with a more specific theoretical framework on tourism research that has examined the phenomenon of Paradores and relates to the concept of authenticity discussed in this study. It then proceeds with a robust and detailed methodology, starting from natural language processing and the creation of an ad hoc thesaurus to the machine learning classification model. The study continues with the analysis of the results and discussions and concludes with a summary of the conclusions and practical implications.

The study presented below is pioneering and innovative for two reasons. Firstly, it addresses the concept of authenticity in Spanish Paradores for the first time. Secondly, it employs an original methodology in this area, based on machine learning.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Spanish Paradores

The study of the tourist phenomenon of Spanish Paradores began in the 1950s, encouraged by the General State Administration itself, as noted by Pérez [9], through research by various public officials belonging to tourism departments such as Fuster, Lavaur, Soriano, Amman, and Vadillo.

The first studies on Andalusian Paradores did not really emerge until the beginning of Spanish democracy, with the unpublished work by Sánchez-Sánchez [10] on the tourist reality of the Paradores of Andalucía, analysing the supply, the buildings, and the locations of the establishments. Also noteworthy is the study carried out by Guarnido-Olmedo et al. [11], which provides an overview of the national Paradores network and its trends within the autonomous region of Andalucía through the statistical analysis of empirical data (number of stays, covers, occupancy rate, profitability, etc.) collected throughout the 1980s.

Until 2013, contributions on the Paradores network were quite scarce. Notable studies include those on the origins and history of the network over its first 75 years of existence [6], the analysis of tourism language on Paradores’ websites [12], the average customer profile [13], or the exploration of the legal aspects of the state-owned company [14].

To situate this policy within a broader European context, it is relevant to establish parallels with similar policies and research on state-owned accommodations in other countries. In this regard, the Pousadas in Portugal represent a significant analogous case. Founded in 1942, the Portuguese Pousadas were created with the aim of promoting tourism and preserving the country’s cultural and architectural heritage [15]. Like the Spanish Paradores, Pousadas are located in historic buildings such as castles, monasteries, and palaces, offering an experience that combines hospitality with local history and culture [16].

In Italy, the “Albergo Diffuso” model is another initiative that shares similarities with Paradores. This concept, which emerged in the 1980s, involves transforming historic buildings and traditional houses in rural villages into dispersed hotel accommodations managed in a unified manner [17]. Although not a state policy in the strict sense, it receives governmental support and has been the subject of research highlighting its role in revitalising rural communities and preserving cultural heritage.

In France, while there is no equivalent state-run accommodation network, programmes such as the “Monuments Historiques” promote the conservation and touristic use of historic and rural buildings [18]. Although mainly managed privately or by local organisations, these programmes receive state support and contribute to cultural and heritage tourism.

These European examples demonstrate that the utilisation of accommodations in historic buildings to promote tourism and preserve heritage is a common trend in Europe. The policy of Spanish Paradores, therefore, is part of a broader context of strategies that seek to combine heritage conservation with sustainable economic and tourism development. This comparative perspective enriches the analysis and allows for a better understanding of the impact and evolution of Paradores in relation to similar initiatives in other European countries.

Pérez [19] initially approached Paradores from an architectural perspective, focusing on the heritage intervention of defensive architecture and the set of heritage assets (monuments and changes in use). The numerous studies conducted by Rodríguez Pérez over the last decade on Paradores located in castles, convents, and monasteries have greatly enriched the knowledge about tourism Paradores. There is a growing interest in the academic study of Paradores, with notable contributions on the former Parador of Sierra Nevada [20], the network of state-owned tourist establishments [21], hotel rehabilitations in Galician heritage sites [22,23,24,25], the network of hostels in Extremadura [26], or the Parador of Zamora [27].

Studies on the origins of real estate promotion and hotel operation between 1911 and 1951 and on the management policy of the network between 1951 and 1962, carried out by Pérez [9], together with contributions by Cupeiro-López [28,29], García-Gutiérrez [30], Ramos [31], Von Hartenstein [32], and Valle-Gómez [33], are currently evolving and being increasingly framed within the field of tourism history. Other studies have complemented specific aspects of the Paradores network, such as the content analysis of online reviews [34], the presence of monumental staircases, the promotion of cultural tourism and the richness of cultural and natural spaces [35,36], the existing artworks [37], the impact of the economic crisis between 2009 and 2015 [38], or the tourism communication of heritage [39]. Additionally, fields related to other hotel chains with similar characteristics to the Spanish Paradores have been developed [40,41].

2.2. The Concept of Authenticity

Authenticity, within the realm of historical and cultural heritage, is a complex and multifaceted notion arising from the interaction between visitors’ perceptions and the cultural presentations they encounter [42,43]. More than merely reflecting an object’s or site’s physical genuineness, authenticity is shaped by each individual’s subjective experience, their cultural background, their expectations, and how they interpret what they perceive [44]. Thus, visitors are drawn not only to verifiable remnants of the past but also to those deeply resonant moments that allow them to connect with a community’s historical and social fabric [45,46].

In this light, authenticity should not be understood as a static trait, but rather as a fluid process in which audiences, heritage professionals, host communities, and cultural narratives intertwine, ultimately shaping tourists’ satisfaction levels and their valuation of the experience [47]. This more discerning and layered understanding of authenticity can stimulate the development of sustainable, culturally responsive tourism practices that cultivate mutual respect and appreciation [48].

Academic interest in authenticity in tourism began with the pioneering work by Dean MacCannell, who introduced the concept of “staged authenticity” [45]. MacCannell argued that while tourists seek authentic experiences, they often encounter staged representations designed to meet their expectations of what authenticity should entail. This phenomenon reflects an inherent tension within the tourism industry, where authenticity can be manipulated to satisfy market demands.

Building on this foundation, Wang [49] expanded the concept of authenticity by identifying three main types: objective authenticity, constructive authenticity, and existential authenticity. Objective authenticity relates to the originality of cultural objects and events, assessing the extent to which something is genuine. Constructive authenticity suggests that authenticity is a social construct, dependent on individual and collective perceptions. Existential authenticity focuses on the personal and subjective experiences of individuals, and how these contribute to an internal sense of authenticity.

Perceived authenticity is crucial in the context of cultural tourism, as it affects tourist satisfaction and perceived value [43]. Reisinger and Steiner [42] contend that authenticity is a psychological construct varying according to individual perceptions, implying it is not inherent in the cultural object or event but is interpreted by the visitor. This highlights the importance of considering tourists’ expectations and perceptions when designing cultural experiences.

Cultural tourism centres on the exploration and understanding of other cultures, and perceived authenticity in these experiences is vital for tourist satisfaction and cultural appreciation [50]. Wang [48] emphasises that authentic experiences in cultural tourism can enhance intercultural understanding and promote respect for other cultures. This underscores the potential of cultural tourism as a tool for fostering intercultural exchange and global understanding.

Various case studies have examined how tourists perceive authenticity in different cultural contexts. For example, Yang and Wall [51] found that tourists seek experiences they consider authentic, even though these experiences are often commercialised and adapted to meet tourist expectations. This illustrates the complexity of managing authenticity in cultural tourism, where representations can be both genuine and manipulated.

Perceived authenticity is also crucial in the context of various forms of tourism, including nature-based tourism, as it affects tourist satisfaction and perceived value [52]. In nature-based tourism, authenticity relates to the unspoilt and pristine quality of natural environments and the genuine interaction with nature [53]. Tourists engaging in nature-based activities often seek a connection with the natural world that is free from artificial enhancements or overt commercialisation [54]. The authenticity of these experiences can enhance environmental appreciation and promote conservation efforts.

For tourism managers, understanding perceived authenticity is essential to designing experiences that meet visitors’ expectations without compromising cultural integrity [55]. García-Almeida [47] suggests that this involves balancing the authentic presentation of culture with adaptations to tourist expectations. Achieving this balance is crucial to developing sustainable and respectful tourism practices that promote cultural appreciation and respect.

3. Methodology

3.1. Rationale for Choosing Andalusian Paradores as a Pilot Study Area

Andalusian Paradores represent an ideal case study for examining authenticity in tourism due to their distinctive integration of cultural heritage and hospitality. These state-owned establishments are not merely accommodations but restored historic buildings—castles, monasteries, and palaces—rich in architectural and cultural significance. They serve as stewards of Spain’s tangible and intangible heritage, blending historical preservation with modern tourism services. For instance, the Parador of Granada, housed within the Alhambra complex, and the Renaissance palace-based Parador of Úbeda exemplify how history and tourism coalesce.

Strategically located in areas of cultural and natural value, including UNESCO World Heritage Sites and protected landscapes, Andalusian Paradores provide visitors with immersive experiences that extend beyond their walls. Unlike standalone heritage monuments, Paradores offer integrated services, including high-quality dining that often reflects regional cuisine, which broadens the scope of cultural engagement. Their state-owned model ensures a focus on heritage conservation alongside sustainable tourism development, distinguishing them from private hotels.

Finally, the network’s consistent standards across diverse settings allow for the systematic analysis of factors influencing authenticity perceptions.

Data for this study were collected from Google Reviews of Andalusian Paradores. Google Reviews is a widely used platform where users can freely share their experiences and opinions about services and establishments. This openness allows for a broad range of perspectives but also introduces reliability limitations, as there is no verification process to confirm that reviewers have actually visited the Paradores.

We describe these reviews as “authentic feedback” in the sense that they reflect personal experiences and perceptions; however, we acknowledge that not all reviews may be genuine or free from manipulation. To address this, we implemented data cleaning procedures to filter out reviews that appeared suspicious or lacked substantive content, such as those with extreme ratings without commentary or multiple reviews from the same user in short intervals.

Another limitation pertains to automatic translation. Google Reviews often include feedback from international visitors who write in their native languages. The platform provides automatic translations into English, but these may suffer from clarity issues or inaccuracies, potentially distorting the intended meaning. We took these translation issues into account by cross-referencing translations with the original text where possible and excluding reviews where the translation was too ambiguous to interpret reliably.

Regarding demographic data such as gender, we inferred this information based on the reviewer’s name provided in the review. However, the authenticity of gender attribution is not fully reliable due to factors like unisex names or cultural variations in naming conventions.

3.2. Data Source and Collection

Sentiment analysis is acknowledged as a valuable methodology in the realm of tourism research for assessing tourist destinations and attractions [56]. This investigation employs an open-source framework that incorporates Python libraries dedicated to scientific computing. The framework is equipped with multiple capabilities, such as data analytics, mining, sentiment analysis, and topic detection. This study particularly targets online User-Generated Content (UGC), harnessing a comprehensive collection of reviews concerning the Paradores of Andalusia, sourced from Google Reviews.

Since its inception in 2007, Google Reviews has grown to become a predominant platform offering substantial information and insights on diverse businesses and services globally. It aggregates and exhibits consumer reviews and ratings, enabling users to convey their views and experiences regarding a broad spectrum of products, services, and locations. The User-Generated Content on Google Reviews serves as a pivotal element, providing detailed and authentic feedback on the standards, services, and overall experiences linked to global businesses. Additionally, the platform incorporates functionalities like Q&A sections for interactive queries and advice, alongside a system to bookmark and organize reviews for later use.

Through web scraping methods, a broad array of review datasets were amassed. This comprehensive compilation consists of all obtainable records (15,867) from Google Reviews regarding Andalusian Paradores (Spain) spanning from early 2013 to mid-2024. These reviews furnish a rich and varied assortment of insights and traveller experiences, forming a substantial base for analysis.

The dataset concentrates on aspects pertinent to guest feedback in the specified categories. Essential metrics analysed include the quantity of comments, their dates, and the content of the remarks (translated into English automatically upon retrieval to aid global comprehension). A new metric was also introduced: the original nationality of the commenter, identified through a function in Google Sheets that discerns language from specific textual patterns, along with the presumed gender of the reviewer inferred from their name. Understanding the diversity in languages and gender representations among the reviews yields critical insights into the varied visitor demographics, supporting the development of tailored communication and marketing strategies to cater to different linguistic and cultural needs.

3.3. Text Pre-Processing and Cleaning

Data preprocessing is recognized as a critical element in all data analysis activities. This procedure involves the thorough cleansing and organizing of datasets to prepare them to be subjected to further analytical techniques [57]. In this research, essential data processing strategies and NLP techniques were employed, focusing on the detection and quantification of subjective components within the texts [58].

The sentiment analysis approach was structured through multiple sequential phases. All text processing steps were performed automatically by using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) library in Python. The initial phase comprised data purification and standardisation, which involved extracting text-based reviews from the collaborative platform Google Reviews. This stage identified the range of languages used, followed by an automated translation into English, the primary language used, to maintain uniformity across the analysis and enable equitable comparisons. The translation was performed by using the Google Translate API, ensuring consistency in language processing. The text was then divided into sentences and subsequently into smaller units called tokens. Tokenisation, the practice of dividing text into smaller elements like words and punctuation, was applied. This was followed by part-of-speech (PoS) tagging, which classifies words into their grammatical categories according to their usage and context. For instance, in “the weather is fantastic”, “weather” is identified as a noun and “fantastic” as an adjective.

The analytical process then moved on to lemmatisation, which involves converting words to their base or root forms, and normalising all text to lowercase. Lemmatisation is designed to reduce words to their simplest form; thus, variations such as “eat”, “eating”, and “ate” are simplified to “eat”.

The concluding stage of the analysis involved employing a list of stop words, like “the”, “and”, or “another”. These are typically words that while common in general text, are considered extraneous in sentiment analysis and topic modelling, as they can skew the interpretation and outcomes of textual evaluations [59,60]. In our analysis, these stop words were excluded to focus on the most meaningful words that contribute to sentiment. By removing these common words by using NLTK’s predefined list of English stop words, we improved the efficiency and accuracy of the sentiment analysis.

3.4. Sentiment Analysis, Data Mining, and Machine Learning

The study engaged a sentiment analysis framework, tool, and lexical repository known as “Valence Aware Dictionary for Sentiment Reasoning” (VADER) [61]. VADER, a rule-based mechanism, is tailored for assessing sentiments within User-Generated Content (UGC). This system automatically assigns each word in the lexicon (either in English or translated into English) a classification of positive, neutral, or negative. It not only assigns scores but also measures the intensity of the sentiment expressed [62]. VADER employs established sentiment lexicons that utilize lexical characteristics commonly indicative of sentiment in social media contexts. The VADER lexicon comprises more than 7500 terms, including abbreviations, acronyms, initials, and icons. It also integrates sentiment analysis tools from the NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit) and is further refined by contributions from the Data Science Lab. VADER assigns a sentiment score to each comment, ranging from −1 for predominantly negative to 1 for a predominantly positive sentiment. It is currently considered an essential benchmark in social media sentiment analysis [63]. Furthermore, this research utilised SentiART, a sophisticated sentiment analysis tool (SAT) that computes four lexical attributes (arousal, emotional potential, valence, and aesthetic potential) and two inter-lexical features (valence span and arousal span) to assess various aspects of sentiment distribution in texts [64]. The four attributes are detailed as follows:

- -

- Arousal refers to the intensity of emotion conveyed in the text, measuring how stimulating or calming the content is.

- -

- Emotional potential assesses the capacity of words to evoke emotions in the reader, indicating how likely a word is to trigger an emotional response.

- -

- Valence indicates the positivity or negativity of the words used, representing the overall sentiment direction.

- -

- Aesthetic potential evaluates the perceived beauty or stylistic quality of the text, reflecting its ability to provide aesthetic pleasure.

- -

- The two inter-lexical features are detailed as follows:

- -

- Valence span, which measures the range of or variability in valence across the text, provides insights into fluctuations between positive and negative sentiments.

- -

- Arousal span, which assesses the variation in arousal levels throughout the text, highlights changes in emotional intensity.

The methodology transformed the textual data into numerical attributes for analysis using a range of statistical and machine learning techniques, including hypothesis testing and classification models. Translating sentiments into numerical scores facilitated the visualization of sentiment distributions across various categories or groups. Student’s t-test was employed to examine if there were statistically significant differences in sentiment scores among different groups. Additionally, machine learning techniques, such as Random Forest, were applied to categorize instances based on their sentiment dimensions and other related attributes.

3.5. Thesaurus

We designed a comprehensive and appropriate thesaurus of terms with multiple synonyms representing the perceived authenticity in the Paradores of Andalusia. The process began with an exhaustive review of the reviews. By using the natural language processing technique of topic modelling, we identified the key terms visitors use to describe authenticity. These terms include words such as “genuine”, “authentic”, “historical”, “traditional”, and “real”. This technique allowed us to analyse large volumes of text efficiently and accurately, detecting patterns and frequencies in language use that might not be immediately obvious.

Once the relevant terms were identified, the next step was to establish the relationships between these terms within the thesaurus. These relationships included synonyms, such as “genuine” and “authentic”, which mean the same, and antonyms, such as “historical” and “modern”, which mean the opposite. It is also important to identify related terms, which are concepts connected in some way, and specific/general terms, which establish a hierarchy among the terms. For example, “traditional” might be related to “cultural”, while “real” might be a more specific term within the general category of “authentic”. Establishing these relationships helps structure the thesaurus in a way that accurately reflects the complexities and nuances of how tourists perceive and describe authenticity in their experiences at Andalusian Paradores.

Additionally, we consulted Roget’s Thesaurus to identify additional synonyms, thereby enriching the thesaurus prior to its integration into analysis software. This resource is structured into six main categories, represented as a tree encompassing over a thousand branches, each containing semantically connected words or “meaning clusters”. While the entries in Roget’s Thesaurus are not always precise synonyms, they represent shades of meaning or a continuum of related ideas. Roget’s Thesaurus has been established as an invaluable tool for assessing semantic similarity; forming lexical chains is straightforward, though their evaluation presents greater complexity [65].

4. Results

4.1. Authenticity and the Evolution of Sentiments

The concept of authenticity is fundamental in tourism, as it often influences tourist satisfaction and loyalty. In the context of Andalusian Paradores, significant differences in the perception of authenticity have been observed according to nationality and gender. Authenticity in tourism is multifaceted, involving objective authenticity (the tangible and historically accurate attributes of a destination) and existential authenticity (the personal experiences and feelings of tourists).

Tourists’ perceptions of authenticity are influenced by their cultural backgrounds and previous experiences [55]. In Andalusian Paradores, significant variations in authenticity perceptions were found among tourists of different nationalities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Significant differences in the perception of authenticity. Student’s t-test.

For example, at the Palacio de Dean Ortega (Úbeda), the t-value was 2.63 with a p-value of 0.009, indicating a statistically significant difference in how authenticity is perceived by tourists of different nationalities. Similarly, the Parador of Cádiz showed a t-value of 2.71 and a p-value of 0.007, while the Parador of Jaén had a t-value of 3.05 and a p-value of 0.002. These significant differences in certain Paradores may be due to their unique historical significance and cultural appeal to different nationalities. Paradores situated in iconic historical sites or with strong cultural narratives might resonate more with international tourists seeking objective authenticity, whereas domestic tourists might focus on the existential aspects of their experience. These variations can be attributed to the distinct cultural frameworks through which tourists from various countries interpret historical and cultural authenticity. Western tourists might prioritise historical accuracy and preservation, whereas Eastern tourists may focus on the experiential and symbolic aspects of authenticity [66].

Gender perspectives in tourism research explore how gender roles and identities shape travel experiences. Significant gender-based differences were also found in perceptions of authenticity in various Paradores. For instance, at the Parador of Ayamonte, the t-value was 1.978 with a p-value of 0.048, indicating a statistically significant difference. The Parador of Jaén had a t-value of 2.2039 and a p-value of 0.028, while the Parador of Málaga-Golf showed a t-value of 2.02263 and a p-value of 0.043. These differences suggest that men and women may prioritise different aspects of authenticity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of reviews reflecting objective and existential authenticity.

Women might value experiential and relational authenticity more, focusing on the social and emotional aspects of their travel experiences. Men, on the other hand, might prioritise objective authenticity, emphasising the factual and historical accuracy of the destination [67,68].

Gender roles and socialisation processes influence how authenticity is perceived. Women are typically described to value relational and emotional connections, which translates into a preference for experiences that feel genuine and personally meaningful (Table 3). Men, influenced by different social expectations, may lean towards a more fact-based appreciation of authenticity, valuing the historical and cultural accuracy of the destinations they visit [69]. Moreover, gendered marketing and tourism practices also play a role. Marketing strategies often target men and women differently, emphasising historical accuracy and adventure for men while focusing on emotional and experiential aspects for women.

Table 3.

Examples highlighting gender-based differences in reviews.

4.2. Classification by Machine Learning Techniques

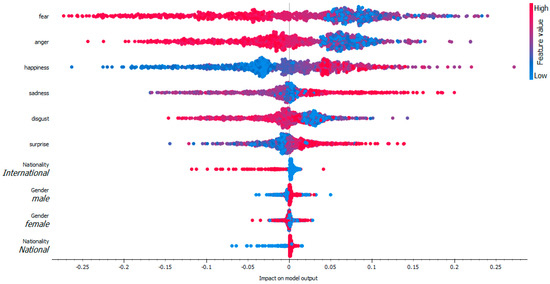

Through the model created by using the Random Forest algorithm and the database of reviews on Andalusian Paradores, the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) plot was generated. We utilized the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) approach to interpret the outputs of our predictive models. SHAP is a game-theoretic method that assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction, based on the concept of Shapley values from cooperative game theory [70]. This technique enables us to decompose the predictions of complex machine learning models into contributions from each input feature, ensuring a consistent and locally accurate explanation of model behaviour. By applying SHAP, we gained valuable insights into how each variable influenced the model’s decisions, enhancing the transparency and interpretability of our results within the context of the study.

This model interpretation tool explains the impact of each feature on the model’s prediction, highlighting the variables that influence the target variable of authenticity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

SHAP plot for Random Forest model predicting authenticity in Andalusian Paradores.

Emotions such as “fear” and “anger” have a significant impact on the perception of authenticity. High values of “fear” and “anger” (indicated by red dots) tend to decrease the perception of authenticity, while low values (blue dots) have a lesser effect, suggesting that the presence of fear negatively impacts tourists’ perceptions. Regarding the feeling of “happiness”, this characteristic is crucial, with higher values (blue dots) positively correlating with the perception of authenticity. Tourists who feel happier are more likely to perceive the Paradores as authentic, which aligns with the general understanding that positive emotions enhance the perception of authenticity. “Sadness”, however, can influence the perception of authenticity regardless of its intensity, likely in a negative direction. High levels of “disgust” (red) negatively impact the perception of authenticity, similar to “fear” and “anger”. Lower values (blue) have a lesser impact, indicating that reducing “disgust” can improve perceptions of authenticity. Finally, “surprise” is shown as a characteristic with mixed impact, as its values can have both positive and negative effects, suggesting that the impact of surprise depends on the context, whether it is a pleasant or unpleasant surprise.

Regarding the demographic characteristics of nationality and gender, interesting results are observed. Tourists from other countries show a diverse impact on the perception of authenticity, with high feature values (red dots) suggesting a positive correlation with authenticity perception. This could imply that international tourists find the cultural and historical aspects of Paradores more intriguing and authentic. However, domestic tourists show a less varied impact, with feature values (blue dots) having minimal influence on the perception of authenticity. This result might indicate that domestic tourists have more specific expectations and can be more critical due to their familiarity with the local culture. In terms of gender, the impact of male tourists on the perception of authenticity shows some variation. Higher feature values (red dots) have a notable influence, suggesting that men’s perceptions can significantly affect the overall authenticity score, possibly due to their emphasis on factual and historical accuracy. However, female tourists exhibit a substantial impact. Higher values (red dots) indicate a strong positive correlation with the perception of authenticity, implying that women’s focus on experiential and relational aspects significantly enhances their perception of authenticity. It is important to note that this focus may be a contributing factor and represents a possible explanation rather than a clear result demonstrated by our analysis. Further research would be necessary to confirm this relationship.

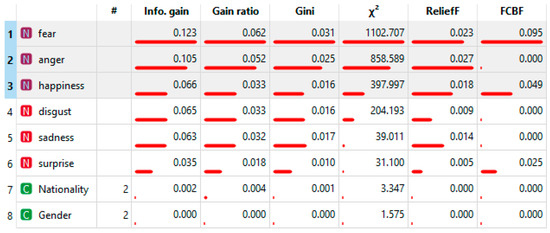

Figure 3 presents various metrics that evaluate the relevance of features such as emotions and demographic data in the model of perceived authenticity. To aid understanding of the concepts used, it is pertinent to provide a brief explanation of the metrics employed in the table.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of feature importance in machine learning model for perception of authenticity in Andalusian Paradores.

For instance, the term “Gain Ratio” measures the relative importance of a feature in constructing the model, adjusting for the inherent bias of features with multiple values. This means it helps identify which features provide the most useful information for predicting the perception of authenticity.

“ReliefF” is an algorithm that assesses a feature’s ability to differentiate between closely related classes in the attribute space, considering how the feature changes in similar instances belonging to different classes. This is particularly useful for identifying features that effectively discriminate between different perceptions of authenticity.

On the other hand, “FCBF” (Fast Correlation-Based Filter) selects features that are both relevant and non-redundant, based on statistical correlations. This method removes features that do not contribute new information to the model, thereby improving its efficiency and accuracy.

The numerical values presented, such as 0.023 or 0.095, reflect normalised scales indicating the relative influence of each feature. A higher value suggests a more significant contribution to the model. For example, a feature with a value of 0.095 has a greater impact on predicting the perception of authenticity than one with a value of 0.023.

The analysis of feature importance metrics reveals that emotions play a crucial role in the perception of authenticity in Andalusian Paradores. In particular, “fear” and “anger” stand out as the most influential emotions, showing the highest values across almost all evaluated metrics, including information gain, gain ratio, and χ2. This suggests that these negative emotions significantly impact how tourists perceive the authenticity of their experience. “Happiness”, although also an important emotion, primarily shows its relevance in the metrics of information gain and χ2, indicating that tourists who experience happiness tend to perceive the experiences as more authentic. On the other hand, “disgust” and “sadness” have moderate importance in the model, implying that these emotions also influence, albeit to a lesser extent, the perception of authenticity. “Surprise” is the emotion with the least impact among those included, though its influence is not entirely negligible.

In contrast, demographic data such as nationality and gender have much less influence on the model. Nationality shows some importance, but it is significantly lower compared with emotions, which could indicate that international and domestic tourists perceive authenticity somewhat differently, although not decisively so. Gender, according to all evaluated metrics, has minimal importance, suggesting that differences in the perception of authenticity between men and women are practically insignificant in this context.

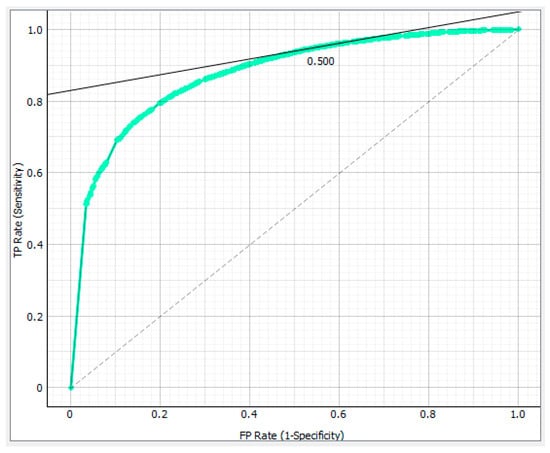

Through the model created by using the Random Forest algorithm and the database of opinions on Andalusian Paradores, the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve was generated (Figure 4). This curve is essential to evaluating the model’s performance in predicting the target variable of authenticity. The model evaluation results are also provided, indicating key metrics such as AUC, CA, F1, Precision, Recall, and MCC.

Figure 4.

ROC curve.

The green line represents the ROC curve, illustrating the model’s performance by depicting the relationship between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (1-specificity). In contrast, the solid black line indicates the accuracy curve at a specific threshold (0.5), serving as a reference point where sensitivity and specificity are evaluated simultaneously. The AUC value is 0.876 for high authenticity (Table 4), confirming that the model has an excellent ability to distinguish between authentic and non-authentic opinions. This high AUC value indicates that the model is highly effective in correctly classifying true positive cases while minimizing false positives. An AUC close to 0.9 signifies robust performance and high discriminative capability, suggesting that the model reliably predicts authenticity perceptions. Such a performance level indicates that the model is well calibrated and capable of generalizing across different datasets, making it a valuable tool for analysing User-Generated Content in the context of tourism.

Table 4.

Model performance metrics for predicting authenticity levels in Andalusian Paradores reviews.

The ROC curve and the evaluation metrics for the authenticity model of Andalusian Paradores demonstrate robust performance with high discriminative capability. These results support the notion that emotions play a crucial role in the perception of authenticity, with negative emotions decreasing and positive emotions increasing perceived authenticity. Demographic factors have a lesser influence.

5. Discussion

5.1. Cultural and Emotional Influences on Authenticity Perceptions

This research underscores how cultural differences significantly shape tourists’ travel behaviours and perceptions. Studies have suggested that tourists from different cultural backgrounds may seek authenticity in varied ways. For example, tourists from Western cultures often value historical preservation and accurate representations in their quest for authenticity [71,72]. Conversely, some research indicates that tourists from Asian cultures may prioritise meaningful and emotionally resonant interactions with destinations [73,74]. However, it is important to recognise that these broad categories encompass diverse groups, including tourists from Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, each with unique preferences and expectations [75].

Our findings align with these perspectives, demonstrating that emotions such as fear, anger, and happiness significantly impact the perception of authenticity in Andalusian Paradores among tourists of various nationalities. Specifically, negative emotions like fear and anger were found to diminish the authenticity experience, while positive emotions like happiness enhanced it. This suggests that emotional responses play a crucial role in how authenticity is perceived across different cultural backgrounds, supporting the idea that tourists’ cultural contexts influence their emotional engagement with destinations [76].

The consistent feelings of happiness and the observed decrease in sadness in our study suggest that Paradores have maintained a high standard of service quality. According to the SERVQUAL model, customer satisfaction is based on service quality dimensions such as tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [77]. Effective crisis management, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, has played a crucial role in stabilising negative emotions like fear and disgust, ensuring tourists’ safety and providing clear communication [78]. Additionally, changes in customer expectations may explain the slight decrease in happiness and increase in anger towards the end of the period, reflecting a growing demand for personalised services and unique experiences.

5.2. Nationality, Gender, and the Scope of Cultural Representation

Differences in perceptions of authenticity based on nationality further support the idea that cultural backgrounds influence how tourists value and interpret authenticity [79]. International tourists may appreciate the historical and cultural uniqueness of Paradores more than domestic tourists, who might apply stricter criteria due to their familiarity with the local culture [51]. Recent studies have shown that international tourists tend to seek experiences representative of the country visited [80], reinforcing the perception of authenticity when these experiences align with their prior expectations.

Gender differences also highlight that men and women prioritise different aspects of authenticity [81]. Women may seek relational and emotional connections, whereas men may focus on historical accuracy [69].

This research highlights how cultural differences significantly shape tourists’ behaviours and perceptions. In our sample, most international tourists were from Western countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States, while tourists from Eastern countries (e.g., Asian countries) represented a small proportion (17%). Therefore, our findings primarily reflect the perspectives of Western international tourists and domestic tourists. We acknowledge that references to “Eastern tourists” are not strongly supported by our data and have adjusted our discussion accordingly.

Western tourists typically seek authenticity aligned with their cultural narratives, valuing historical preservation and accurate representations [71,72]. This finding aligns with our results, where emotions such as fear, anger, and happiness significantly influenced perceptions of authenticity in Andalusian Paradores. Negative emotions such as fear and anger tend to diminish the authenticity experience, while positive emotions such as happiness enhance it.

In our dataset, “happiness” was the most prevalent emotion, detected in 89% of reviews, indicating that the majority of tourists had positive experiences at Paradores. Negative emotions were less frequent: “sadness” appeared in 9% of reviews, “anger” in 16%, “fear” in 4%, “disgust” in 11%, and “surprise” in 69%. These percentages demonstrate that while negative emotions are present, they are less common but have a significant impact on perceptions of authenticity when they occur.

The persistent sense of happiness and the observed reduction in sadness in our study suggest that Paradores have consistently provided high-quality services. According to the SERVQUAL model, customer satisfaction stems from various service quality dimensions, including tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [77]. Skillful crisis management, particularly throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, has been crucial in reducing negative emotional responses like fear and disgust by ensuring tourist safety and maintaining clear communication (Weng et al., 2022). Additionally, the observed shift in customer satisfaction towards a slight decline in happiness and a rise in anger towards the study’s conclusion may reflect evolving expectations, with a growing demand for personalised services and authentic experiences. The differences in perceptions of authenticity based on nationality provide further evidence that cultural backgrounds play a key role in how authenticity is perceived [79]. In our sample, international tourists, comprising 63% of respondents, likely place greater value on the historical and cultural uniqueness of the Paradores compared to domestic tourists, who may hold stricter criteria due to their familiarity with local culture [51]. Previous research supports the notion that international tourists often seek culturally representative experiences that align with their preconceived notions [80], further reinforcing the authenticity of such experiences. Gender differences also reveal contrasting priorities in authenticity, with women perhaps favouring emotional and relational connections, and men focusing more on historical accuracy [69,81].

The sustained positive emotional responses, coupled with the decrease in sadness observed in our findings, indicate that Paradores have successfully maintained a high level of service quality. Drawing upon the SERVQUAL model, customer satisfaction is predicated on dimensions such as tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [77]. The effective management of crises, including those arising during the COVID-19 pandemic, has proved vital for mitigating adverse emotional reactions such as fear and disgust, as well as for ensuring tourist safety and delivering transparent communication [78]. Moreover, evolving customer expectations may account for the slight reduction in happiness and the increase in anger towards the end of the assessment period, suggesting that visitors increasingly demand personalised services and distinctive experiences.

The influence of cultural background on authenticity perceptions is further exemplified by notable differences between nationalities. In this regard, prior research underscores that cultural origin shapes how authenticity is understood and valued [79]. Within our sample, international tourists—who comprised 63% of participants—appeared more inclined to appreciate Paradores’ historical and cultural uniqueness than domestic tourists, who may have applied more stringent criteria owing to their greater familiarity with the local context [51]. As highlighted in recent studies, international visitors often seek experiences that embody the essence of the destination country [80], thus reinforcing authenticity when expectations align with the experiences encountered.

Gender-based differences also emerged, indicating that men and women may prioritise varying aspects of authenticity [81]. Whilst women may place greater value on relational and emotive connections, men may be more concerned with the historical fidelity of the offering [69].

However, our analysis indicated that gender had minimal influence on perceptions of authenticity, as evidenced by its low importance in our model. This suggests that while gender differences exist in the tourism literature, they were not strongly evident in our data. It is possible that the specific context of Andalusian Paradores or the composition of our sample influenced this result, and further research is required to explore this aspect in greater detail.

6. Conclusions

The study found that cultural backgrounds shape how tourists perceive authenticity in Andalusian Paradores, with international visitors, mainly from Western countries, generally valuing historically faithful and accurately represented experiences, whereas domestic tourists apply more stringent criteria. Emotions play a key role: happiness was by far the most common emotional response, suggesting overall satisfaction and service quality, while negative emotions—though less frequent—significantly undermined perceived authenticity. Over time, effective crisis management, such as during COVID-19, helped minimise fear and disgust, and changes in customer expectations explained slight decreases in happiness and increases in anger. Although the sample primarily represented Western perspectives, these findings indicate that both cultural background and emotional responses inform how authenticity is judged. Gender showed minimal effect, implying that within this context, authenticity perceptions transcend simple demographic distinctions.

Despite offering valuable insights, this study’s findings are subject to several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. The sample predominantly reflected Western international visitors, potentially overlooking the nuanced perspectives of Eastern tourists or other cultural groups and limiting the generalisability of our results. Additionally, while certain emotional responses were identified and linked to authenticity perceptions, more granular analyses are necessary to understand how and why these emotions arise, interact, and evolve over time. Further investigations could integrate real-time feedback mechanisms and advanced analytical tools to capture more dynamic, context-specific emotional data and better isolate the influence of cultural, demographic, and situational factors. Similarly, although gender emerged as having minimal importance in this context, future studies may explore whether different types of heritage sites, marketing strategies, or cultural narratives provoke varying gender-based responses. Ultimately, expanding the geographical scope, employing longitudinal designs, and experimenting with innovative data collection methods will provide richer, more comprehensive evidence to guide tourism managers, heritage professionals, and policymakers in refining authenticity-driven strategies and fostering sustainable, culturally sensitive visitor experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, V.C.-F. and V.M.-F.; methodology, V.C.-F. and I.R.-R.; validation, V.C.-F., M.P.-C. and I.R.-R.; formal analysis, V.C.-F. and M.P.-C.; investigation, V.C.-F., M.P.-C. and I.R.-R.; resources, V.C.-F.; data curation, V.C.-F. and M.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C.-F., M.P.-C. and I.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, V.C.-F., M.P.-C. and I.R.-R.; visualisation, V.C.-F. and M.P.-C.; supervision, I.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data has been collected from the public platform of Google.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer; World Tourism Organisation: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Estadística de Movimientos Turísticos en Frontera (FRONTUR); Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.ine.es/uc/JtaQBzp8 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- INE. Encuesta de Gasto Turístico (EGATUR); Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.ine.es/uc/ILuMdMXc (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Fernández-Fuster, L. Albergues y Paradores; Temas Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 1959; n° 309; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Garrido, A. Historia del Turismo en España en el Siglo XX; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Samper, M. Paradores, 1928–2003: 75 Años de Tradición y Vanguardia; Paradores de Turismo de España S.M.E., S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, C.V.; Armand, E.H. Introducción al Turismo: Análisis y Estructura; Editorial Centro de Estudios Ramon Areces SA: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ley 4/1990, de 29 de Junio, de Presupuestos Generales del Estado para 1990. Boletín Oficial del Estado, Núm. 156, de 30 de Junio de 1990. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1990-15347 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Pérez, M.J. La Red de Paradores: Arquitectura e Historia del Turismo 1911–1951; Paradores de Turismo de España S.M.E., S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, N. Paradores Andaluces; Trabajo inédito depositado en la Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE): Sevilla, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnido-Olmedo, V.; Gámez-Navarro, J.; Martínez-Quesada, G.Y. Los Paradores Nacionales y Andalucía; Cámara Oficial de Comercio e Industria de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Calvi, M.V. El lenguaje del turismo en las páginas web de los Paradores. In Textos y Discursos de Especialidad; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Núñez, J. El Mercado Nacional. El Cliente de Paradores. In Proceedings of the Perspectivas de Futuro del Sector Turístico Hotelero, La apuesta de Paradores, Madrid, Spain, 22–25 June 2005; Universidad Internacional Menéndez Pelayo (UIMP): Madrid, Spain, 2006; pp. 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos-Martín, M.M.D. Aspectos Histórico-Jurídicos de la Entidad Estatal Empresarial Paradores de Turismo; Documentación Administrativa; 2011; pp. 259–260. Available online: https://revistasonline.inap.es/index.php/DA/article/view/5557/5611 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- da Silva, N.P.; de Francisco, A.C.; Thomaz, M.S. Turismo rural como fonte de renda das propriedades rurais: Um estudo de caso numa pousada rural na Região dos Campos Gerais no Estado do Paraná. Caderno Virtual Turismo 2010, 10, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Prista, M. From displaying to becoming national heritage: The case of the Pousadas de Portugal. Natl. Identities 2015, 17, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montis, A.; Ledda, A.; Ganciu, A.; Serra, V.; Montis, S. Recovery of rural centres and “Albergo Diffuso”: A case study in Sardinia, Italy. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versaci, A. The evolution of urban heritage concept in France, between conservation and rehabilitation programs. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 225, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.J. La Rehabilitación de Construcciones Militares para uso Hotelero: La Red de Paradores de Turismo (1928–2012). Ph.D. Thesis, E.T.S. Arquitectura (UPM), Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Fernández, J.V. Aspectos tecnológicos, matéricos e industriales de la arquitectura del turismo de nieve: El caso del parador nacional de Sierra Nevada. In Proceedings of the III Jornadas Andaluzas de Patrimonio Industrial y de la Obra Pública, Málaga, Spain, 23–25 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Garrido, A.; Pellejero-Martinez, C. The State-owned Tourist Establishments Network (1928–1977), need for hotels or tourism policy? Rev. Hist. Ind. 2015, 59, 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- Crecente, M. Paradores.: Pasado, presente y futuro de la relación patrimonio y turismo: El caso de la Ribeira Sacra. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, J.M.G. Desde los paradores de Verín y del Castillo de Monterrei. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Diz, A.G. Del Hospital Real de Santiago al Parador de los Reyes Católicos.: Un edificio emblemático del arte gallego. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Aspres, A.L. Monumentos convertidos en hoteles: El sacrificio de la memoria arquitectónica. El caso de Santo Estevo de Ribas de Sil. Pasos Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2017, 15, 673–685. [Google Scholar]

- Abujeta-Martín, A.E. Intervención en el Patrimonio Arquitectónico Extremeño: La Red de Hospederías. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura (UEX), Badajoz, Spain, 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10662/3900 (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Bragado, D.L.; Sánchez, V.A.L. El palacio de los Condes de Alba de Aliste y su transformación en parador nacional de turismo de Zamora. Espac. Tiempo Forma Ser. VII Hist. Arte 2017, 5, 391–416. [Google Scholar]

- Cupeiro-López, P. La influencia del turismo en el patrimonio construido. Un caso paradigmático: La Red de Paradores de Turismo. In Turismo y Desarrollo Económico: IV Jornadas de Investigación en Turismo; Facultad de Turismo y Finanzas: Sevilla, Spain, 2011; pp. 609–623. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11441/53078 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Cupeiro-López, P. Viajar a través del tiempo. El reto cultural de Paradores. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- García-Gutiérrez, J. A propósito de paradores y de la intervención en edificios históricos en la España Contemporánea. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.H. La Red de Paradores de Turismo de España. Aproximación a su historia, diagnóstico actual y propuestas de futuro. Tur. Rev. Estud. Tur. Canar. Macarones. 2017, 6, 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hartenstein, F.M.B. La coexistencia de la Empresa Nacional de Turismo (1951–1985) con Paradores como departamento ministerial, y su posterior evolución como empresa pública en el sector turístico español. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Valle-Gómez de Terreros Guardiola, M. Del La restauración de monumentos en España al inicio de la red de Paradores: Antonio Gómez Millán en Mérida. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Medina, M.L.; Hernández-Estárico, E.; Morini-Marrero, S. Study of the critical success factors of emblematic hotels through the analysis of content of online opinions: The case of the Spanish Tourist Paradors. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 27, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupeiro-López, P. Paradores y sus señas identitarias. El arte de la travesía, la cultura del territorio. Estud. Tur. 2022, 224, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Campos González, S. El fomento del turismo cultural desde el sector público. Adm. Cid. Rev. Esc. Galega Adm. Pública 2014, 9, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Munuera, M.G. Las obras de arte de Paradores: Descubrir una colección. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sestayo, R.L.; Fernández, E.F.; Giménez, M.N.S. Impacto de la crisis económica en la estructura económico-financiera de Paradores SA. RICIT Rev. Tur. Desarro. Buen Vivir 2017, 11, 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- González, E.L. Paradores y comunicación turística del patrimonio. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, S. Pousadas de Portugal: Entre Albergue de carretera y Parador. Estud. Tur. 2019, 217–218, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.J.R. Paradores, Pousadas y Habaguanex. La rehabilitación en el marco de la hotelería pública. Cuad. Tur. 2015, 35, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C.J. Reconceptualizing Object Authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A.; Recuero-Virto, N.; Eren, R.; Blasco-López, M. The role of authenticity, involvement and experience quality in heritage destinations El rol de la autenticidad, la involucración y la calidad de la experiencia en los destinos patrimoniales. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2024, 20, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, P.; Franzese, A. The authenticity of self: Conceptualization, personal experience, and practice. Sociol. Compass 2008, 2, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.K.; Lee, T.J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Almeida, D. Knowledge transfer processes in the authenticity of the intangible cultural heritage in tourism destination competitiveness. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Tourism and Modernity: A Sociological Analysis; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Authenticity in ethnic tourism: Domestic tourists’ perspectives. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xu, J.; Sotiriadis, M.; Shen, S. Authenticity, Perceived Value and Loyalty in Marine Tourism Destinations: The Case of Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.; Campón-Cerro, A.; Alves, H. Authenticity in environmental high-quality destinations: A relevant factor for green tourism demand. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, A.; Khoshkam, M.; Mohamad, D.; Kadir, I. Linking nature-based tourism attributes to tourists’ satisfaction. Anatolia 2017, 28, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Su, Y.; Su, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L. Perceived Authenticity and Experience Quality in Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Kunqu Opera in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabreel, M.; Moreno, A.; Huertas, A. Do local residents and visitors express the same sentiments on destinations through social media? In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2017: Proceedings of the International Conference in Rome, Italy, 24–26 January 2017; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 655–668. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, J.D.; Mac Namee, B.; D’arcy, A. Fundamentals of Machine Learning for Predictive Data Analytics: Algorithms, Worked Examples, and Case Studies; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B.; Lee, L. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2008, 2, 1–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, D. Quantitative Stopword Generation for Sentiment Analysis via Recursive and Iterative Deletion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.01519. [Google Scholar]

- Ghag, K.; Shah, K. Comparative analysis of effect of stopwords removal on sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computer, Communication and Control (IC4), Indore, India, 10–12 September 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, A.; Boldt, M. Using VADER sentiment and SVM for predicting customer response sentiment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 162, 113746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014; Volume 8, No. 1. pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Bonta, V.; Janardhan, N.K.N. A comprehensive study on lexicon based approaches for sentiment analysis. Asian J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8 (Suppl. S2), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.M. Sentiment analysis for words and fiction characters from the perspective of computational (neuro-)poetics. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmasz, M. Roget’s thesaurus as a lexical resource for natural language processing. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1204.0140. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, D.; Kocher, S. Perception of Sacredness at Heritage Religious Sites. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 912–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M.B. Gender in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Yu, H.; Tseng, Y. The impact of cultural differences on travel behavior and perception. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M. The Leadership Styles of Women and Men. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Li, A.; Zhou, L. Review Study of Interpretation Methods for Future Interpretable Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 191969–191985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, Y. Deconstructing the internal structure of perceived authenticity for heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Gilbert, D. Measuring Tourists’ Emotional Experiences toward Hedonic Holiday Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L.W. Cross-Cultural Behaviour in Tourism: Concepts and Analysis; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; No. 20615. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.Y.; Wang, C.H. Emotional labor of the tour leaders: An exploratory study. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumral, N.; Önder, A. Tourism, Regional Development and Public Policy: Introduction to the Special Issue. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 1441–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen, M.; Lub, X.D.; Mitas, O.; Jung, T.H.; Ascenção, M.P.; Han, D.I.; Moilanen, T.; Smit, B.; Strijbosch, W. Emotions as core building blocks of an experience. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Measuring service quality: Is SERVQUAL now redundant? J. Mark. Manag. 1995, 11, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Wu, Y.; Han, G.; Liu, H.; Cui, F. Emotional State, Psychological Resilience, and Travel Intention to National Forest Park during COVID-19. Forests 2022, 13, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.; Curran, R.; O’Gorman, K.; Taheri, B. Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiarta, I.P. The cultural characteristics of international tourists. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Tour. Events 2018, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roothman, B.; Kirsten, D.; Wissing, M. Gender Differences in Aspects of Psychological Well-Being. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2003, 33, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).