Abstract

Heritage has increasingly emerged as a pivotal medium for driving and adapting to change, and as an integral component of innovation ecosystems. In the ongoing participatory turn in governance, the management of collective heritage resources reflects a broader paradigm shift aimed at fostering sustainable socio-technical transformations. Far from being static relics of the past, heritage assets function as dynamic agents of innovation, thus influencing various dimensions of contemporary life. This research sheds light on heritage as a vibrant force for transformation and adjustment, showcasing its ability to position itself as a crucial component that both enables and guides broader processes of innovation. It emphasises how heritage sites, characterised by their transitional nature and ‘ex’ and ‘post’ identities, have become arenas for creative regeneration and socio-cultural, technical, territorial, and knowledge-based innovation. By utilising helical models and Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction, this article underscores the transformative power of heritage to address global disruptions through heritage-driven innovations, drawing on three heritage and creative destruction categorizations. This highlights how heritage actively shapes innovative knowledge spaces while fostering urban and social regeneration, positioning it as a vital tool for rebuilding and reimagining sustainable futures. By exploring diverse local heritage transformation initiatives across different regions, this research unveils three heritage helix models that showcase the dynamic process of change management through heritage. These models offer a framework for guiding future heritage projects, fostering innovative knowledge spaces and inspiring sustainable transformations.

1. Introduction

The concept of a ‘global city’ provides a crucial perspective for understanding globalisation’s effects on cities and the impacts of new social and economic regulations on urban life [1,2]. This highlights spatial reorganisation and suggests that global cities have become key nodes in production, finance, telecommunication networks, culture, creativity, and innovation due to globalisation [3,4]. The notion of the global city emerges from the process identified as the post-Fordist ‘transformation’, which commenced with the transition from industrial production to financial markets. In this new process, cities and the reorganisation of their physical, economic, and social spaces are regarded as significant sources in generating the elements of transformation [1,5]. Global cities often experience rapid urban changes driven by creative destruction, such as privatisation, de-institutionalisation, and commodification, making these concepts deeply interconnected [6]. These diverse societal, cultural, and economic shifts and obstacles raise questions regarding the potential benefits and implications of destruction and its capacity for reconstruction and transformation [7]. Creative destruction, though disruptive, can trigger recovery and sustainable transformation through creative regeneration and heritage-driven innovations. Cultural heritage sites in urban centres are frequently abandoned due to urban decentralisation, deinstitutionalisation, and deindustrialisation, and possess regeneration and innovation potential. These sites can be revitalised as innovation spaces, contributing to SDG 11’s aim of ‘sustainable cities and communities’ by fostering societal, cultural, environmental, and economic innovations. However, this potential can also bring significant risks. Heritage-driven innovations reconnect these spaces to contemporary life but risk commodifying heritage or creating enclosures that limit accessibility and inclusivity. Mitigating risks to the fullest extent possible necessitates collective intelligence and the proper administration and regulation of heritage-related resources. Understanding the emergence and operation of heritage-driven innovation spaces is essential to ensure heritage remains a driver of sustainable and equitable change, rather than a market commodity [8,9] (p. 304). Moreover, the commodification of cultural heritage extends beyond the scope of urban regeneration initiatives. A significant number of heritage resources are affected by this phenomenon [10,11,12,13].

Heritage is acknowledged as a ‘contemporary product’ [14] (p. 20) and a form of property subject to ownership [15,16]. Legally, four ownership types were identified: state, private, group, and free access [17]. These evaluations elucidate the viewpoint from which cultural heritage is presently integrated into modern society. From this perspective, heritage resources are no longer perceived as static artefacts or areas solely under the jurisdiction of states. Instead, heritage resources are regarded as valuable assets worldwide that facilitate access to knowledge and innovation through effective management approaches, encompassing the active participation of diverse actors based on the multi-stakeholder approach to cultural heritage [18]. Heritage encompasses diverse construction and reconstruction processes as well as instances of creative destruction [19], involving a dynamic interplay of the past, present, and future, knowledge, events, information, expert communities, emotions, and institutions. Indeed, heritage represents a form of knowledge that has yet to be fully integrated into conventional management practices [20].

Recent research has focused on integrating cultural heritage with innovation concepts. Existing studies on heritage management and innovation models emphasise democratic and participatory approaches involving collaborative partnerships across the public, private, and tertiary sectors, including civil society [21]. These approaches centre on governance and innovation strategies predicated on helical models [22,23]. However, a significant gap remains in the literature regarding the positioning of heritage as an innovation ecosystem or within innovation ecosystems. Current studies have often overlooked the role of heritage stakeholders and governance approaches in innovation and knowledge systems. This omission limits a comprehensive understanding of how and where heritage-driven innovation has emerged and been implemented in practice and its potential to contribute to sustainable transformation in the heritage field [24]. Moreover, research on heritage within ecosystem studies typically adopts ecological and landscape-oriented methodologies, failing to adequately address the role of heritage sites in innovation ecosystems [25] (p. 223).

This article aims to investigate the complex management challenges and emerging areas of heritage-driven innovation that arise following the repurposing of heritage sites, particularly those described with ‘ex-’ and ‘post-’ prefixes across various European contexts. It seeks to contribute to the underexplored literature on cultural heritage management and heritage within and as an innovation ecosystem. It utilises diverse transformation initiatives to examine how and where heritage-driven innovation ecosystems emerge and transform the globalised world. In this context, this study is guided by a fundamental research question: How can the various governance strategies in heritage transformation projects, particularly those shaped by creative destruction, contribute to the development of heritage helix models that facilitate diversity and understanding of the dynamics of heritage-driven innovation spaces in post-transformation contexts? What heritage-driven innovation spaces emerge from these transformation processes, and how can they inform future projects? This paper begins with an exploration of heritage management strategies and the concept of innovation ecosystems, subsequently proceeding to an examination of heritage assets within these ecosystems. It employs a qualitative approach based on exploratory, three-pair case studies. To substantiate arguments derived from the existing literature on heritage management, innovation ecosystems, and helix approaches, the methodology and case study selection criteria were delineated. The findings introduce three heritage helix systems and management frameworks that can be implemented globally and locally [26] to drive the transformation through heritage-innovation spaces. The article concludes with a discussion and recommendations for future research and the identification of potential areas for further investigation.

1.1. Participatory Turn in Heritage Management

The pluralisation of heritage discourse has significantly altered the approaches employed in heritage management. Significant social, economic, and cultural changes in the late 20th century, including neoliberal policies, sustainability concerns, and climate change, have shaped the perception, conservation, and management of cultural heritage. There has been a transition from a ‘material-based approach’ to a ‘value-based approach’ [27]. The former approach treats heritage in a centralised, authoritative manner, guided by experts. In contrast, the latter adopts a more contemporary people-centric stance, emphasising a framework that involves negotiating actors. The term heritage is no longer used to describe the items that central authorities choose to solidify their legitimacy or establish a national identity. Rather, it includes components of the past that society has chosen to incorporate into the present day, whether for economic, cultural, political, or social reasons [28]. In the heritage field, social, cultural, and economic values significantly influence the selection of ‘what to preserve’ and ‘how to preserve’ [29].

Loulanski [30] describes the evolving heritage debate as shifting ”from monuments to people, from objects to functions, and from preservation to sustainable use and development”. Jansenn et al. [31] classify heritage into three approaches: ‘sector, factor, and vector’. These approaches evolved sequentially but did not replace each other entirely; instead, they complemented one another. The sector approach, which was dominant until the late 20th century, treated built environments as museum objects, mainly involving experts and heritage authorities. The factor approach views built heritage as an economic resource, engaging stakeholders from the tourism, construction, and real estate sectors. The current vector approach focuses on intangible heritage such as knowledge, traditions, and memories linked to artefacts and sites. Moreover, Stanojev and Gustafsson [32] developed heritage models 1.0–3.0, emphasising stakeholder interactions, value exchange, and value compromise.

The contemporary heritage management and governance models in the literature emphasise the democratic nature of heritage. These models draw inspiration from the eco-museum approach [33], its diverse empirical studies, and concepts such as participatory heritage [34,35]. Additionally, scholars and the international community, including the UN, UNESCO, and ICOMOS, incorporate partnership approaches in heritage management, which involve collaboration at the public, civil, and private levels [36,37,38]. Scholars from various disciplines have independently examined these intricate processes to address different aspects. These include studies on austerity urbanism [24,39,40], shared heritage ownership [41], and the role of social empowerment and participatory planning [35]. Researchers have also explored social justice and innovation [42], the public sector’s involvement in heritage [43], the private sector’s engagement with heritage [21,44,45], and public–civil–private engagement in heritage [36,46]. This study integrates these concepts to provide a more comprehensive perspective on heritage management and elucidate heritage-driven innovations, propelled by processes that transform them through heritage, utilising a case-based evidence-supported investigation.

1.2. Heritage Within Innovation Ecosystem

An innovation ecosystem primarily reflects the economic dynamics and sustainable growth inherent in the intricate relationships amongst actors or entities aimed at addressing cultural, societal, technological, environmental, and planetary challenges [47,48]. The widely accepted definition is linked to the level of novelty in knowledge creation processes. According to the standardised OECD definition [49], “[a]n innovation is a new or improved product or process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and that has been made available to potential users (product) or brought into use by the unit (process)” [49] (p. 20). However, this definition does not encompass the activities, interactions, and locations through which and where innovation may occur [50,51]. Through collaborations among a variety of stakeholders, including governmental bodies, cultural organisations, academic institutions, and the private sector, innovation ecosystems can enhance the creation and execution of groundbreaking solutions [51]. These interactions facilitate the exchange of knowledge, resources, and expertise, resulting in the development of innovative projects, products, and services [50,52]. Despite the increasing attention directed towards the study of innovation ecosystems [53,54,55], the phenomenon of their emergence remains largely underexplored.

Innovation in services denotes the application of novel concepts, technologies, or methodologies to enhance and refine service delivery processes. Cultural service innovation aims to cultivate and enhance human values while improving the quality of life of the public. Conventional cultural management models and technologies typically disregard people-centric cultural services ([47] (p. 4) and [54,56]). The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) [56] defines cultural ecosystem services as the “nonmaterial benefits people obtain from ecosystems through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation, and aesthetic experiences” [56] (p. 40). Moreover, it classifies ten subcategories of cultural ecosystem services. Cultural heritage and knowledge systems are among these subcategories. Unlike other ecosystem services, cultural ecosystem services are arguably more easily perceived and appreciated. Consequently, they play a vital role in raising public awareness and in promoting sustainable development. However, these services are amongst the most challenging to quantify, both in monetary and numerical terms, as well as to qualify in terms of how individuals derive benefits from them. Consequently, the complete integration of cultural ecosystem services within the ecosystem services framework and their incorporation into decision-making and management processes has proven challenging [56] (p. 212).

The concept of innovation is increasingly recognised for its complexity, involving multiple stakeholders with both complementary and conflicting interests. Research indicates the growing significance of collaborative endeavours within the realm of innovation processes. Most studies have concentrated on the factors influencing the efficacy of partnerships among various actors [57] (p. 1083). Innovation ecosystems comprise networks of public and private entities, formal institutions, and other organisations that collaborate to transform regions, cities, knowledge, culture, or customs into innovation and entrepreneurship hubs, thereby fostering valuable new knowledge [58]. The establishment of horizontal and vertical partnerships has been prioritised since the implementation of the networking innovation model. These hierarchical systems of governance acknowledge that innovation is a decentralised function in which all ecosystem stakeholders contribute rather than the purview of any one sector [59,60]. Understanding the innovation ecosystem and knowledge-to-innovation process relies on innovation policy analysis in particular sectors and the triple-helix model, which involves partnerships among governments, industries, and universities [61,62,63,64]. The model extends to the quadruple helix, which includes society and end users [65], and the quintuple helix, which adds to the environment and sustainability [66]. Scholars have assessed the strengths and weaknesses of these models, emphasising their potential in various innovation ecosystems [67]. Despite extensive research on innovation ecosystems, few studies have distinguished between the different approaches and sectors [68]. In the field of heritage, whilst numerous studies have explored helix models in relation to specific heritage types [69,70], the connection between innovation and heritage remains unclear.

Furthermore, heritage is often included in ecosystem studies; however, a consensus remains elusive regarding the place of cultural heritage within the framework of ecosystem services [56] (p. 219). Heritage ecosystems encompass cultural traditions, historical sites, legends, institutions, technologies, and infrastructure within varied natural, cultural, virtual, digital, and geographical contexts [71]. These ecosystems continually evolve through creative destruction processes, necessitating heritage management as a form of change management [31,72]. Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction refers to the process of dismantling established orders and systems, subsequently leading to the emergence of innovation through the reconstruction of the previous structures [19,73]. This denotes the process of replacing outdated inventions and technologies with new alternatives [74]. The concept of creative destruction emphasises its twofold impact: while it brings about challenges such as privatisation, urban regeneration, and societal disparities, it simultaneously fosters economic development and technological advancement through reconstruction. This reconstruction process can also stimulate regional and local development efforts despite causing community displacement and changes in the use of public spaces and the collective benefits of cultural ecosystems. Avrami [7] examined how creative destruction drives innovation within the heritage sector. This transformative process is apparent in various aspects of the heritage landscape, including the shift in heritage assets to private ownership, the privatisation of public areas and heritage, the standardisation of urban environments by multinational corporations, the commodification of cultural heritage and practices for tourism, and the neglect of historic buildings due to the decline in traditional manufacturing industries [11,75,76].

Creative destruction in heritage ecosystems has also led to the creation of diverse co-innovation networks, forming their own innovation ecosystems. Heritage is integral to the innovation and development of ecosystems, providing economic, cultural, and intellectual capital. It is marketed in various segmented marketplaces [28,77] and shapes our lives by defining relationships, policies, projects, and resources [78]. Heritage involves diverse management processes and knowledge forms that are continuously generated by various stakeholders [20]. The characteristics of these stakeholders also influence the overall performance and success of innovation [57] (p. 1083). This perspective necessitates re-evaluating heritage-driven innovation ecosystems and governance models, focusing on heritage as an ecosystem and its pervasive influence while acknowledging its role in change management. In heritage ecosystems, generating both implicit and explicit knowledge challenges the identification of innovative outcomes [71].

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a qualitative descriptive–interpretive methodology to investigate heritage ecosystems through a comparative analysis of heritage transformation projects in diverse local contexts, focusing on their emergent heritage-led innovation. The research employs a tripartite approach: first, data collection and processing to establish a conceptual framework on heritage management and innovation ecosystems through a literature review, archival records, and project documentation; second, an in-depth analysis to examine governance models, stakeholder involvement, and post-intervention heritage outcomes, focusing on spatial, historical, social, and cultural contexts to identify patterns of transformation; and third, a synthesis of findings to develop and evaluate ‘heritage helix models’ that represent archetypes of heritage transformation. Case studies from Germany, Italy, and Türkiye were selected based on criteria such as heritage categories, official conservation decisions and challenges, ownership by legally ‘rightful’ stakeholders, and multi-actor collaboration. Paired case studies with shared attributes, such as ownership structures, collaboration levels, and categories of creative destruction as transformation catalysts, were utilised to validate the applicability of the models across different contexts. By integrating contentious conservation strategies, this study elucidates three distinct heritage management approaches, offering insights into how heritage ecosystems support sustainable and innovative transformation.

The proposed heritage helix framework employs comparative case analysis to uncover the central themes that enable the global replication of heritage-driven innovation approaches. Three key factors shape the diversity of case pairings. The first centres on selected forms of creative destruction—privatisation, de-institutionalisation, and commodification—which serve as transformative processes, converting heritage locations into innovation centres, while redefining stakeholder duties. The second factor emphasises collaborative schemes in heritage administration, highlighting the importance of multi-sector partnerships among public, private, and civil entities in driving innovation. The third factor pertains to common challenges or criticised aspects such as physical, cultural, or social accessibility barriers.

The initial pair of case studies (See Table 1) examines the transformation of post-industrial sites through privatisation. Beykoz Kundura1 in Istanbul, repurposed as a film and cultural hub, and Spinnerei in Leipzig, a thriving cultural complex, exemplify collaborations between private entities, third-sector organisations and the wider public. While these initiatives successfully foster cultural and territorial innovation as ‘innovation zones’, they have been subject to criticism regarding their limited public access, a persistent issue in post-industrial heritage sites. The selected examples present new heritage-driven innovation spaces for addressing these challenges. The second pair (See Table 2) examines marginal heritage sites that struggle to gain recognition for their cultural and historical significance. These locations, transformed via de-institutionalisation, include the neuropsychiatric hospitals in Arezzo (Pionta) and Florence (San Salvi), which have been partially converted into university facilities, healthcare centres, and community spaces. These examples illustrate the challenges of reclaiming such sites as heritage whilst demonstrating how public–private-civil collaborations can promote civic engagement and social innovation spaces to reclaim these places. The third pair (See Table 3) addresses symbolic and disputed heritage sites, many of which remain abandoned because of stakeholder conflicts or are repurposed for tourism through commodification. The Hanlar2 district in Ankara and Galataport Istanbul exemplify transformations into cultural and commercial hubs via public–private partnerships, incorporating museums, shopping areas, and leisure facilities. Whilst these initiatives often face criticism for their neoliberal underpinnings and contentious heritage management practices, they nonetheless contribute to sustainable development. They do so by improving accessibility, incorporating urban heritage assets into contemporary life, and nurturing diverse innovation spaces centred around heritage. Though these paired case studies may not present entirely new methods of collaboration or heritage intervention, they provide valuable insights into the heritage-driven innovation spaces that emerge from these transformations in response to particular challenges. Each pair illustrates how the processes of creative destruction and cooperative management can inform heritage-led innovation, providing important lessons for balancing conflicting interests, encouraging public engagement, and promoting sustainable development in similar post-intervention contexts.

Table 1.

A summary of the pair cases of Model 1.

Table 2.

A Summary of the pair cases of Model 2.

Table 3.

A summary of the pair cases of Model 3.

2.1. Pair Cases

2.1.1. Privatisation as Creative Destruction: Management of Privately Owned Industrial Heritage Sites

Beykoz Kundura stands as a notable cultural icon that has experienced various phases of industrial, modern, and global development. Initially established as a tannery in 1810, it was later restructured in 1882 to include shoe-manufacturing facilities. The complex was influenced by intercultural and technological exchanges from diverse regions into Istanbul, resulting in a series of ownership changes for those who operated the site. In the 2000s, Türkiye’s post-industrial landscapes transformed with the rise of new cultural industries in urban settings, as exemplified by Beykoz Kundura’s conversion into a film plateau. This period was of critical importance for this post-industrial site, as its privatisation facilitated the establishment of Kundura Memory, a non-profit cultural organisation formed in response to negative public sentiment regarding privatisation. Initially, Kundura Memory aimed to emphasise the site’s industrial culture and history by focusing on the Sumerbank community through social media to enhance public access and gain trust. Subsequently, it initiated public engagement for heritage conservation and dissemination. As Beykoz Kundura’s profile increased through films, social media, and public engagement, Kundura Memory evolved into a research centre, incorporating curators, industrial heritage experts, sociologists, pedagogues, and artists. This development led to a new cultural programme transforming social relations, such as the Vardiya sessions, where artists drew inspiration from Beykoz Kundura’s private archive to create artworks, and educational sessions for children to explore the historic site. The programme also includes guided tours conducted by Sumerbank community volunteers, offering visitors insights into the site’s history through personal narratives [79,80,81].

Similarly, in the 2000s, Leipzig’s administrative actors used post-industrial areas as political tools to reshape the city’s image and eliminate its ‘industrial dirty past’. The concept of a creative, knowledge-based city was adopted as part of the national and local cultural policy, leading to the modernisation of the cultural policy framework. Spinnerei in Leipzig began transforming into a cultural hub in the early 1990s, housing artists who had been displaced due to political biases in the late 1980s through informal placemaking. These artists temporarily repurposed vacant industrial spaces, aiding the site’s transformation and Leipzig’s heritage. In 2001, Heintz & Co., Tilmann Sauer-Morhard, Bertram Schultze, and Karsten Schmitz acquired the campus, driving its evolution into an artist community [82,83]. The conversion of Halle 14 into a sustainable heritage venue for non-profit use, with a 40-year lease to a cultural foundation for exclusive non-profit activities, ensured its public utility [84]. The establishment of ‘Archiv Massiv’, a non-profit foundation serving as a museum, exhibition space, and research centre dedicated to preserving the site’s industrial history, exemplifies Spinnerei’s positive and democratic approach [85].

2.1.2. De-Institutionalisation as Creative Destruction: Common-Based Management of Former Psychiatric Hospitals

De-institutionalisation, initially linked to mental health and intellectual disability, gained momentum in the 1960s and the 1970s, originating in the UK, the US, and Italy before spreading throughout Europe, Scandinavia, and the Antipodes [86]. Policies led to the downsizing or closure of large psychiatric hospitals, causing their decay and abandonment in the 1990s [87]. Pionta Park in Arezzo, spanning 12 ha with a medieval history, became a psychiatric hospital in 1896. It evolved into an isolated area due to the development of the Psychiatric Hospital of Arezzo, which included buildings for various mental diagnoses; service areas such as a water reservoir, a kitchen, and an agricultural space; scientific facilities such as a laboratory, a library, and an archive; administrative buildings; and therapeutic areas for ergotherapy and socialisation [88,89,90,91]. Similarly, San Salvi in Florence, covering 32 hectares, developed as a psychiatric hospital in 1886, featuring facilities for internees, a scientific lab, a water reservoir, ergotherapy areas, and a cinema. After the 1990s closures prompted by de-institutionalisation and 1978 law no. 180, these sites underwent integrated regeneration, addressing environmental, urban, social, and cultural dimensions, and have recently become hubs for civil engagement and social activism. Pionta Park and its facilities are jointly owned by the ASL—Local Health Authority of Southeast Tuscany, Province of Arezzo, Municipality of Arezzo, and the University of Siena. The park hosts the Istituto Tecnico Industriale Statale (Galileo Galilei), primary school Modesta Rossi, and kindergarten Istituto Comprensivo Statale IV Novembre. It also includes the music school Scuola di Musica—Le 7 Note [89,90]. Similarly, the San Salvi area contains The Local Health Authority (ASL) of the Tuscany Region (Central Italy) offices and laboratories, the University of Florence facilities, the scientific high school Antonio Gramsci, the technical school Giuseppe Peano, the tourism hospitality institute Aurelio Saffi, and the primary and secondary schools of Andrea del Sarto, all within an urban park [92].

2.1.3. Commodification as Creative Destruction: Public–Private Partnerships in Heritage Transformations

Since the 2000s, Türkiye’s neo-liberal-driven social, political, and economic transformation has reshaped cultural heritage management, aligning it with city branding to enhance global competitiveness. Particularly in major urban centres, heritage sites—commodified since the 1980s—continue to undergo substantial transformations [93,94,95,96]. These transformations have been facilitated through public–private collaborations, with international and local companies assuming a significant role. Their contributions encompass the establishment of innovation spaces (physically) via museums, cultural centres, and touristic hubs, as well as the sponsorship of restoration and renovation initiatives. The Hanlar District in Ankara has undergone revitalisation as a cultural and tourism centre through public–private partnerships, focusing on the adaptive reuse of historic inns. The Rahmi M. Koç Museology and Culture Foundation undertook the restoration of Çengel Han and Çukur Han, transforming them into a museum, boutique hotel, and restaurant under long-term leases. Limited government funding necessitated the leasing of state-owned structures to private entities for preservation and sustainable reuse. Despite initial administrative and financial challenges, Çengel Han reopened as the Rahmi M. Koç Çengelhan Museum in 2005, followed by Çukur Han as a boutique hotel in 2010. Before its transformation, Ankara’s Hanlar District was largely abandoned with only mohair and leather sellers, hardware stores, and coppersmiths. Fires and neglect severely damaged the inns, and by the late 20th century, they were entirely deserted. Çukur Han was even listed among the World Monuments Fund’s 100 sites in need of preservation in 2008. Koç Holding’s investment revitalised the area by introducing art workshops, antique shops, cafés, restaurants, and private museums. These changes have attracted investors, tradesmen, tourists, and students, turning the district into one of Ankara’s most vibrant cultural and tourism hubs.

Galataport Istanbul, a public–private collaboration, spans 1.2 km on Istanbul’s European coast, covering 400,000 square metres, with a cruise port, hotel, retail, dining, offices, and museums. It revitalises the historical pier into a hub for shopping, gastronomy, culture, and arts, featuring the Peninsula Istanbul Hotel, opened in 2023 at Karaköy Dock, known for converting heritage sites into luxury accommodation. Investors have had 30-year operational rights in the port area since 2013. The project enhanced public coastline access with an innovative cruise port and underground passenger terminal with a unique cover system. This opened up Karaköy’s previously inaccessible coastline for public use amid controversy. This advanced system directs vehicle traffic underground and preserves the historic port for Galataport customers. Currently, the coastline hosts cultural and artistic workshops, luxury stores, and restaurants. Until the 2010s, Karaköy was home to small manufacturers and craftspersons. Despite controversies, the project has created a vibrant tourism and cultural space but accelerated gentrification, replacing traditional craftspeople with a global entrepreneurial elite and reflecting broader neoliberal urban development trends.

3. Findings and Results: Transforming Heritage into Innovation Spaces

This study examines the selected pair cases through a multidisciplinary lens, drawing on literature that explores heritage transformations in five distinct categories: (i) territorial dynamics [97] (district, neighbourhood, or regional development); (ii) cultural and knowledge-based intellectual capital [71] (benefiting from culture and heritage through abstract and intangible ways); (iii) social heritage [98] (community-driven initiatives aimed at addressing local needs such as engaging and empowering beneficiaries, reshaping social relations, and improving access to resources and influence); (iv) educational frameworks shaped by collaborative policies, agreements, and pacts [41]; and (v) policy frameworks (tourism and cultural development). These categories represent efficacious responses to specific challenges and limitations pertaining to physical, cultural, and social accessibility as well as engagement barriers. Rather than analysing these categories in isolation, this study adopts a holistic approach to elucidate the emergence and manifestation of these innovation spaces within these cases and through specific acts. By examining the intersections of these ecosystems, it reveals the mechanisms driving diversity in adaptive reuse and the creation of cultural, social and tourist hubs. This approach not only elucidates the roles of various stakeholders, but also demonstrates how these overlapping domains collectively foster cultural exchange, social inclusion, and economic vitality, offering heritage-driven solutions to overcome urban challenges and redefining the urban fabric (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Selected pair cases and heritage-driven innovations.

3.1. Model 1: Privately Owned Industrial Heritage Management and Heritage-Driven Innovations

The regeneration of former industrial complexes such as Beykoz Kundura in Istanbul and Spinnerei in Leipzig demonstrates the significant role of industrial heritage in facilitating regional and community development. These sites exemplify the delicate equilibrium between preserving collective memory and revitalising peripheral urban areas, typically situated on city outskirts. Through the cultivation of innovative cultural, creative, and community-oriented initiatives, these rejuvenated locations serve as catalysts for both territorial and social advancement [97]. The regeneration processes at Beykoz Kundura and Spinnerei illustrate the development of heritage-driven innovation ecosystems, shaped by distinct management strategies. Both venues have evolved into creative centres that sustain cultural production in the aftermath of de-industrialisation. Beykoz Kundura has redefined its identity through cinematic productions, theatrical performances, cultural workshops, and events, while Spinnerei has established itself as a hub for contemporary art, accommodating artists’ studios, galleries, and regular exhibitions. These endeavours not only preserve the industrial legacy but also engage the public through various modalities such as art festivals, exhibitions, and community-led activities, ensuring their continued relevance in contemporary society [81].

Governance at these sites reflects a judicious balance between private ownership and public interest (See Figure 1). In Beykoz Kundura, private proprietors have integrated commercial ventures with cultural and non-profit programming, supported by initiatives such as Kundura Memory, which is dedicated to preserving the site’s industrial and social heritage. Similarly, Spinnerei operates as a privatised entity that incorporates accessibility and inclusivity into its model, offering public events and exhibitions alongside its commercial activities. Both sites adapt to public feedback, expressed through social media, direct interactions, and participation in cultural programming, to shape their role within their respective communities. Local authorities also play a significant role in the governance of Beykoz Kundura and Spinnerei by ensuring compliance with heritage preservation regulations. This includes maintaining museum sections, facilitating non-commercial public uses, and conducting regular inspections to uphold the sites’ cultural significance. Collaborations between site managers, local authorities, and stakeholders reinforce the alignment of these spaces with public benefit, ensuring their ongoing contribution to local heritage and identity. Initiatives such as Kundura Memory and Archiv Massiv address potential conflicts arising from the privatisation of formerly public spaces. Through the preservation of collective memory and the facilitation of public participation, these foundations foster a shared sense of ownership over the sites, aligning their development with the expectations of local communities. The societal responses and collective memories associated with these locations underscore their significance as cultural touchstones, influencing their integration into local life. Despite operating within distinct cultural and national frameworks, the experiences of Beykoz Kundura and Spinnerei demonstrate a common commitment to innovation, inclusivity, and public engagement. These localised governance models reflect societal expectations in Turkey and Germany, illustrating how the adaptive reuse of industrial heritage can generate sustainable benefits for communities while preserving the cultural and historical significance of these unique urban landmarks.

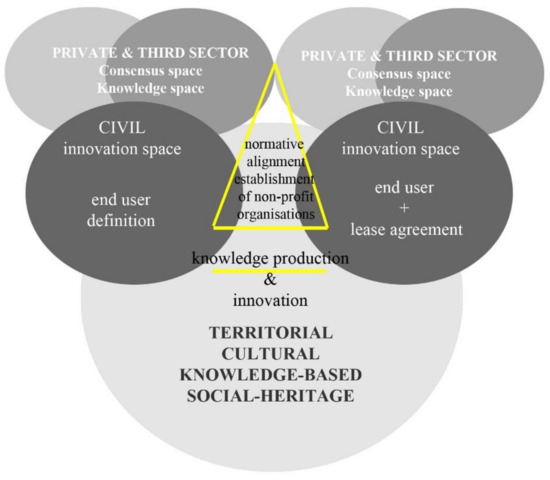

Figure 1.

Model 1, Emerging Innovation Spaces in Post-industrial Landscapes (elaborated by the authors based on Cai’s neo-helix elaboration [63]).

The triple-helix model, frequently used in analysing transformation processes and multi-sector collaborations, serves as a foundation for understanding these governance schemes, particularly in industrial heritage sites [99]. This model, alongside other frameworks focused on sustainability [100], co-creation, and creative industries [101,102], provides valuable insight into the development of innovative ecosystems in heritage transformation projects. Our paired case analysis highlights the presence of triple-helix spheres in heritage management, despite limited public sector involvement. These spheres include the private sector (legal owners) and public reactions (wider public), which represent the driving forces behind transformation, creating spaces for knowledge and innovation. Non-profit organisations function as democratic forums, both online and in physical spaces, although the degree of democratisation and engagement remains complex and challenging in these cases. These transformative endeavours, frequently initiated by legal proprietors to validate their operations, are instrumental in legitimising controversial changes under the guise of public benefit, as exemplified by the Kundura Memory and Archiv Massiv foundations. These not-for-profit knowledge hubs serve as virtual and physical venues for civic engagement, providing various participatory programmes, or facilitating public input to ensure broader representation. Additionally, they foster territorial innovation by creating spaces for underrepresented groups or by offering opportunities for artists to undertake their cultural productions. These instances facilitate cultural and knowledge-driven innovation by introducing novel cultural functions aligned with the transformation, including exhibitions, workshops, research facilities, archives, and established non-profit organisations. Although it is challenging to define these intangible innovation domains, they are fundamentally connected to the rejuvenation of these locations, revitalising various cultural forms. End users experience a range of cultural phenomena that enhance the intellectual capital of culture. These are also associated with social innovations, as evidenced by activities such as online petitions, community discussions, and themes centred on local welfare and empowerment, all of which are reflected in the quotidian interactions within these heritage environments (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Innovation actions of model 1.

3.2. Model 2: Common-Based Heritage Management and Heritage-Driven Innovations

Former psychiatric institutions have emerged as significant focal points for fostering heritage communities, which subsequently facilitates their reclamation as marginal urban spaces. The transformation of San Salvi in Florence and Pionta Park in Arezzo exemplifies the potential of marginal heritage sites to become spaces for emancipation, cultural revitalisation, and community engagement. Both examples highlight how creative and artistic interventions can drive the reclamation of stigmatised places and reshape their identities and roles within urban contexts [91]. The cases have evolved into vibrant community centres driven by artistic efforts and citizen-led urban initiatives and self-governance. Cultural activities, performances, and workshops have helped these spaces overcome historical stigma and foster communal identity and ownership. This collaborative common-based approach [41,103,104,105] has been key in forming heritage communities that are actively involved in reclaiming and managing these areas, making the process more democratic. Creative practices, along with educational and participatory initiatives, are crucial for reimagining these spaces for community engagement and shared cultural heritage. Both instances illustrate how art and culture catalyse social innovation, promoting empowerment, well-being, and place attachment. They highlight the effectiveness of collective governance and grassroots involvement in transforming marginalised spaces into inclusive hubs that celebrate creativity and community spirit. San Salvi and Pionta Park exemplify the transformative potential of integrating cultural and artistic practices into heritage management, creating dynamic spaces for interaction and collective meaning making through local people.

At present, the two case studies under examination encompass a diverse array of cultural and educational organisations and individuals (See Figure 2). Recent spontaneous activities at San Salvi and Pionta Park have highlighted the necessity for an integrated production centre, focused on a self-managed community. This collective comprises professionals from the arts, culture, and entertainment sectors, including creative practitioners, scholars, and members of the public engaged in cultural pursuits. Its permanent physical location is in these extensive former psychiatric institutions equipped with essential facilities for creative output, such as performance spaces, an expansive park, former therapeutic buildings which are currently utilised as university facilities and for other purposes, and a structure accessible to all users (social aggregation centres), facilitating the production of both artistic and cultural works, as well as quotidian gatherings. In accordance with civic engagement principles, the current inhabitants of San Salvi and Pionta Park are effectively assuming the role traditionally held by those responsible for preserving and advancing artistic and cultural heritage. The administration and event planning for these examples have implemented a participatory approach, orchestrated through a public management assembly and specific thematic working groups accessible to all participants. These groups not only focus on event scheduling but also aim to facilitate dialogue, collaboration, and exchange amongst them, fostering an environment conducive to both collective production and community engagement.

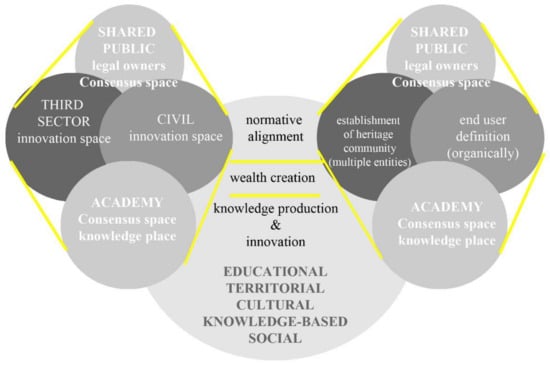

Figure 2.

Model 2, heritage helix ecosystem for shared public ownership (elaborated by the authors based on Cai’s neo-helix elaboration [63]).

Our research identifies five categories of innovation within the ecosystem of these initiatives (See Table 6): (i) Territorial innovation: community-driven social activism and DIY placemaking have enhanced the perception of these stigmatised areas, transforming them into more accessible and valued spaces. (ii) Intellectual capital development: participatory activities employing artistic, creative, educational, and playful methods contribute to intellectual and cultural growth. (iii) User-centric spaces: the end users of these spaces are organically defined during participatory processes, aligning with community needs and project objectives. (iv) Third-sector engagement: the involvement of non-profit organisations and foundations in collaborating with universities has been crucial for implementing these initiatives, fostering civic engagement, and promoting empowerment, education, and well-being. (v) Common-based governance models offer fertile ground for studying social innovation ecosystems, enabling marginal heritage sites to be transformed into centres for knowledge, innovation, and community well-being. Unlike the strategies employed for post-industrial landscapes, the reclamation of these sites relies on grassroots efforts by residents, collaborative governance, and innovative tools, such as civic crowdfunding. These efforts address the stigma associated with these spaces while fostering place attachment, empowerment, and social innovation. Through these approaches, sites such as San Salvi and Pionta exemplify the potential for heritage communities to reclaim urban spaces, challenge negative perceptions, and revitalise these areas as dynamic and inclusive hubs of activity.

Table 6.

Innovation spaces of Model 2.

3.3. Model 3: Public–Private Partnership in Heritage Management and Heritage-Driven Innovations

The cases of the Hanlar district in Ankara and Galataport Istanbul elucidate the intricate dynamics of public–private partnerships (PPPs) in the conservation and transformation of historical sites. While private sector involvement frequently addresses the financial and operational limitations of the public sector, it concurrently raises significant concerns regarding the commodification of cultural heritage (See Figure 3). Through substantial investment, private entities have enhanced the visibility and accessibility of these sites, thereby drawing attention to their cultural significance. However, this process often prioritises economic objectives over the intrinsic values of heritage [106,107]. In both instances, private-sector contributions played a pivotal role in the reimagination of underutilised historical spaces. By leveraging financial resources, investors facilitated infrastructural improvements and enhanced public access to sites that might otherwise have remained neglected. These endeavours not only elevated societal awareness of Istanbul’s and Ankara’s historical and cultural assets, but also redefined these sites as integral components of urban life and tourism. Nevertheless, this emphasis on accessibility and functionality often aligns with commercial interests rather than holistic heritage preservation or social integration. For instance, the branding of these sites as luxury destinations—whether as a modernised waterfront site at Galataport or an upscale hospitality venue at the Hanlar district—reflects the growing trend of heritage resources being reinterpreted as marketable commodities [108].

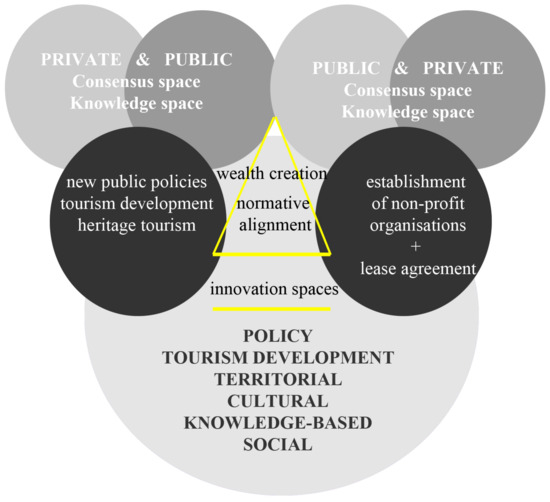

Figure 3.

Model 3, heritage helix ecosystem for public–private partnerships (elaborated by the authors based on Cai’s neo-helix elaboration [63]).

While these initiatives undoubtedly enhance tourism development and foster community engagement, they also risk reducing heritage to a mechanism for socioeconomic gain [109,110,111,112]. The reputational and economic benefits accrued by private entities frequently supersede the broader public value of cultural heritage. In the case of Galataport, the transformation of a historic port into a commercial and cultural hub exemplifies how private investment can overshadow traditional narratives and the intrinsic historical significance of such spaces. Similarly, the Hanlar district’s integration of historical materials into its identity primarily serves to attract a global clientele, potentially marginalising its original cultural context. Nonetheless, despite these risks of commodification and overtourism, these transformations may also catalyse alliances among diverse actors—including residents, public authorities, and private investors—toward the establishment of tourism communities. Such communities can foster a more inclusive approach by involving local residents in the decision-making and transformation processes, thereby balancing economic imperatives with cultural preservation. For example, in the Hanlar district, local artisans and shopkeepers have been integrated into the revitalization effort, enabling them to maintain their livelihoods while contributing to the site’s evolving identity. Similarly, Galataport’s emphasis on creating open public spaces has reconnected residents with Istanbul’s waterfront, offering opportunities for civic engagement and cultural exchange alongside tourism activities (See Table 7). PPPs, by involving local communities, mitigate risks by anchoring development in residents’ lived experiences and cultural memories. As stewards of heritage sites, residents help preserve authenticity and communal value while benefiting from tourism’s socioeconomic opportunities. Although PPPs offer financial and operational support for conserving historical sites, they also pose challenges. Heritage commodification in such partnerships may jeopardise authenticity, risking cultural integrity for economic gain. Yet, collaborative and inclusive approaches can achieve sustainable conservation, balancing economic development with historical and communal preservation. Future strategies should prioritise participatory governance, empowering communities to ensure heritage conservation aligns with both public and private interests without compromising cultural integrity.

Table 7.

Innovation spaces of Model 3.

4. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Recommendations

Heritage serves as a critical mediator of innovation, playing a transformative role not only in shaping urban environments, but also in influencing societal, cultural, and technical structures and governance. Like knowledge and innovation, heritage is a dynamic force within ecosystems of change, contributing to the redefinition and enrichment of urban and social landscapes. This article examined three distinct heritage helix ecosystems, each providing a unique insight into heritage-led transformation and governance. The initial model spotlights industrial heritage ecosystems where privately owned locations are transformed into cultural centres, acting as contemporary innovation hubs. Although these changes show potential, their restricted inclusivity and accessibility often impede wider societal involvement. Consequently, this model emphasises the importance of incorporating democratic and participatory frameworks into governance structures to ensure that heritage serves as a platform for inclusive public engagement. The second model concentrates on marginalised and stigmatised urban areas, demonstrating how collaborative and common-based governance mechanisms can foster genuine innovation and social activism. These instances show the potential for undesirable urban spaces to be reimagined as dynamic, community-driven environments, promoting cultural and social rejuvenation through heritage-led initiatives. The third model investigates heritage ecosystems within the context of public–private partnerships (PPPs), particularly in globalised and contested urban settings. Case studies from Türkiye illustrate how PPPs utilise cultural heritage resources to establish innovation zones, tourist hubs, and cultural centres. Despite concerns regarding commodification and public interest, these partnerships have shown their ability to improve accessibility to public spaces such as coastlines, encourage urban renewal, and stimulate economic and cultural vitality.

This research contributes significantly to heritage management within the realm of innovation ecosystem studies while broadening the existing helix-related innovation literature in an urban context. Although the analysis is based on paired case studies from specific contexts, their depth and alignment with the established literature offer crucial insights into the development and assessment of management frameworks. This study also addresses various aspects of innovation spaces, such as territorial, social, educational, and policy-related aspects, highlighting the adaptability of these models. While recognising certain limitations, such as geographically restricted examples and the uneven representation of innovation spaces across models, this study establishes a foundation for further exploration. Future research should aim to expand the scope of this topic by including diverse geographical and cultural contexts and enhancing our understanding of how helix models can reshape heritage management globally. These findings underscore the transformative potential of heritage-driven innovation, encouraging scholars and practitioners to reconsider heritage as a dynamic and inclusive force within modern ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; methodology, G.Y.; software, G.Y.; validation, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; formal analysis, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; investigation, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; resources, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; data curation, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; writing—review and editing, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; visualisation, G.Y. and A.H.-V.; supervision, G.Y. and A.H.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are profoundly grateful to all those who contributed to this study, whether through their involvement in interviews, sharing of expertise, or provision of resources. We would like to express our sincere thanks to the University of Siena and the Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences (DISPOC) for the financial contribution, which made the publication of this article possible through their support of the Open Access charge.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Kundura is the Turkish term for “shoe”. |

| 2 | Han is the Turkish term for a traditional “inn structure”. Hanlar is the plural version of the term. |

References

- Sassen, S. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormann, B. Global city networks and the nation-state: Rethinking a false tradeoff. In Research Handbook on International Law and Cities; Aust, H.P., Nijman, J.E., Marcenko, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Block, T.; Van Assche, J.; Goeminne, G. Unravelling urban sustainability.: How the Flemish City Monitor acknowledges complexities. Ecol. Inform. 2013, 17, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, P.; Wild, P. SME internationalisation and the role of global cities: A tentative conceptualisation. Int. J. Export. Mark. 2018, 2, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. Cities and the Geographies of “Actually Existing Neoliberalism”. Antipode 2002, 34, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. The creative destruction of cities. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, E. Creative Destruction and the Social (Re) Construction of Heritage. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2020, 27, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philo, C.; Kearns, G. Selling Places: The City as Cultural Capital, Past and Present; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, S.K. Cultural heritage as a resource for property development. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2017, 8, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, I.; Mignosa, A. Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, S.F. Creative Destruction and Neoliberal Landscapes: Post-industrial Archaeologies Beyond Ruins. In Contemporary Archaeology and the City: Creativity, Ruination, and Political Action; McAtackney, L., Ryzewski, K., Eds.; Oxfrod University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C.J.A.; de Waal, S.B. Revisiting the model of creative destruction: St. Jacobs, Ontario, a Decade later. J. Rural Stud. 2009, 25, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, H. Geoffrey Wall Creative destruction: The commodification of industrial heritage in Nanfeng Kiln District, China. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunbridge, J.; Ashworth, G. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kobylinski, Z. Cultural Heritage: Values Ownership. In Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristian Kristiansen; Bergerbrant, S., Sabatini, S., Eds.; Bar International S2508; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 719–724. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. What is Heritage. In Understanding the Politics of Heritage; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, J. Against cultural property. In Archaeological Heritage and Ownership; Duckworth: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, J. Culture and Class; Counterpoint British Council: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Babić, D.; Vatan Kaptan, M.; Masriera Esquerra, C. Heritage Literacy: A Model to Engage Citizens in Heritage Management. In Cultural Urban Heritage; Obad Šćitaroci, M., Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B., Mrđa, A., Eds.; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, C. Public Built Cultural Heritage Management: The Public-Private Partnership (P3). In Transdisciplinary Multispectral Modeling and Cooperation for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Moropoulou, A., Korres, M., Georgopoulos, A., Spyrakos, C., Mouzakis, C., Eds.; TMM_CH 2018; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Bugdol, M. Sharing Heritage through Open Innovation—An Attempt to Apply the Concept of Open Innovation in Heritage Education and the Reconstruction of Cultural Identity. Heritage 2024, 7, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naramski, M.; Herman, K.; Szromekm, A.R. Process of a Former Industrial Plant into an Industrial Heritage Tourist Site as Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2022, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanipour, A. Temporary use of space: Urban processes between flexibility, opportunity and precarity. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkarinen, S.; Tuisku, O.; Hennala, L.; Melkas, H. Robotics in Finnish welfare services: Dynamics in an emerging innovation ecosystem. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 1513–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, D. Transnational Architecture and Urbanism: Rethinking How Cities Plan, Transform, and Learn; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sully, D. Conservation Theory and Practice. Materials, Values, and People in Heritage Conservation. In Museum Practice; Macdonald, S., Leahy, H., Eds.; The International Handbooks of Museum Studies; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.; Tunbridge, J. A Geography of Heritage, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, E.; Mason, R.; De La Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report; The J. Paul Getty Trust: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Loulanski, T. Revising the Concept for Cultural Heritage: The Argument for a Functional Approach. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2006, 13, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Luiten, E.; Renes, H.; Stegmeijer, E. Heritage as sector, factor and vector: Conceptualizing the shifting relationship between heritage management and spatial planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojev, J.; Gustafsson, C. Circular Economy Concepts for Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Implemented Through Smart Specialisations Strategies. In Proceedings of the STS Conference Graz, Graz, Austria, 6–7 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, M.; Murtas, D. Ecomusei il Progetto; IRES: Turin, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sokka, S.; Badia, F.; Kangas, A.; Donato, F. Governance of cultural heritage: Towards participatory approaches. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2021, 11, 2663–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roued-Cunliffe, H.; Copeland, A. Participatory Heritage; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Žuvela, A.; Šveb Dragija, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Partnerships in Heritage Governance and Management: Review Study of Public–Civil, Public–Private and Public–Private–Community Partnerships. Heritage 2023, 6, 6862–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Cheong, C. The Role of Public-Private Partnerships and the Third Sector in Conserving Heritage Buildings, Sites, and Historic Urban Areas; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Guidebook on Promoting Good Governance in Public-Private Partnerships; UN: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, M. The Permanence of Temporary Urbanism: Normalising Precarity in Austerity London; Amsterdam University Press: Croydon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, E. Navigating pop-up geographies: Urban space–times of flexibility, interstitiality and immersion. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaione, C.; De Nictolis, E.; Santagati, M.E. Participatory Governance of Culture and Cultural Heritage: Policy, Legal, Economic Insights from Italy. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 708–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, A.; Cicellin, M.; Consiglio, S. Social bricolage and social business model in uncertain contexts: Insights for the management of minor cultural heritage in Italy. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2023, 27, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupot, Z. Foreign Direct Investments, Cultural Heritage and Public Private Partnership: A Better Approach for Investors? Ann. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2020, 30, 2. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3804293 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Borin, E. Public-Private Partnership in the Cultural Sector: A Comparative Analysis of European Models; Peter Lang Verlag: Bruxxeslles, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mannino, F.; Mignosa, A. Public Private Partnership for the Enhancement of Cultural Heritage: The Case of the Benedictine Monastery of Catania. In Enhancing Participation in the Arts in the EU: Challenges and Methods; Ateca-Amestoy, V.M., Gingsburgh, V., Mazza, I., O’Hagan, J., Prieto-Rodriguez, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boniotti, C. The public–private–people partnership (P4) for cultural heritage management purposes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.-R.; Chi, H.-L.; Yang, J.-Y.; Chien, K.-M. Towards a City-Based Cultural Ecosystem Service Innovation Framework as Improved Public-Private-Partnership Model—A Case Study of Kaohsiung Dome. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallonsten, O. Empty Innovation. In Causes and Consequences of Society’s Obsession with Entrepreneurship and Growth; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. “Oslo Manual 2018|READ Online.” OECD iLibrary. 2018. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oslo-manual-2018_9789264304604-en (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Jackson, D.J. What Is an Innovation Ecosystem? National Science Foundation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2011; Available online: http://erc-assoc.org/sites/default/files/topics/policy_studies/DJackson_Innovation%20Ecosystem_03-15-11.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Marzocchi, C.; Uyarra, E.; Flanagan, K.; The Manchester Institute of Innovation Research (MIOIR). Understanding Innovation and Innovation Ecosystems. 2019. Available online: https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/media/1907/gmipr_tr_understandinginnovationandinnovationecosystems.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Vasconcelos Gomes, L.A.; Figueiredo Facin, A.L.; Salerno, M.S.; Ikenami, R.K. Unpacking the innovation ecosystem construct: Evolution, gaps and trends. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 136, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedehayir, O.; Mäkinen, S.J.; Ortt, J.R. Roles during innovation ecosystem genesis: A literature review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 136, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hølleland, H.; Skrede, J.; Holmgaard, S.B. Cultural Heritage and Ecosystem Services: A Literature Review. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2017, 19, 210–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Faria, P.; Lima, F.; Santos, R. Cooperation in innovation activities: The importance of partners. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Thompson, P. Entrepreneurship, innovation and regional growth: A network theory. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 103–128. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43553080 (accessed on 1 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, M.; Ye, W. The adoption of sustainable practices: A supplier’s perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breschi, S.; Lissoni, F. Knowledge Spillovers and Local Innovation Systems: A Critical Survey. Ind. Corp. Change 2001, 10, 975–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university-industry-government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, P.; Giordano, S.; Farouh, H.; Yousef, W. Modeling the smart city performance. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 25, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. Towards a new model of EU-China innovation cooperation: Bridging missing links between international university collaboration and international industry collaboration. Technovation 2022, 119, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Suwala, L.; Delargy, C. Helix Models of Innovation and Sustainable Development Goals. In Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F. ‘Mode 3’ and ‘Quadruple Helix’: Towards a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 46, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnkil, R.; Järvensivu, A.; Koski, P.; Piirainen, T. Exploring Quadruple Helix. Outlining User-Oriented Innovation Models; Tampereen Yliopisto: Tamperen, Finland, 2010; Available online: http://urn.fi/urn:isbn:978-951-44-8209-0 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Cai, Y.; Lattu, A. Triple Helix or Quadruple Helix: Which Model of Innovation to Choose for Empirical Studies? Minerva 2022, 60, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-S.; Phillips, F.; Park, S.; Lee, E. Innovation ecosystems: A critical examination. Technovation 2016, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyagung, E.; Hani, U.; Azzadina, I.; Sianipar, C.; Ishii, T. Preserving Cultural Heritage: The Harmony between Art Idealism, Commercialization, and Triple-Helix Collaboration. Am. J. Tour. Manag. 2013, 2, 22–28. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2272645 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Sun, L. The Protection and Development of Rice Paper as a Human Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Perspective of the Triple Helix. Acad. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Bejinaru, R. Intellectual Capital of the Cultural Heritage Ecosystems: A Knowledge Dynamics Approach. In Knowledge Management, Arts, and Humanities; Handzic, M., Carlucci, D., Eds.; Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, G.; Rippon, S. Europe’s Landscape: Archeologists and the Management of Change; EAC, Occasional Paper 2; EAC: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McCraw, T.K. Prophet of Innovation. In Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Neo-Liberalism as Creative Destruction. Geogr. Annaler. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2006, 88, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, P.; Punch, M. Urban Governance and the ‘European City’: Ideals and Realities in Dublin, Ireland. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 864–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, G. Heritage and entrepreneurial urbanism: Unequal economies, social exclusion, and conservative cultures. Urban Res. Pract. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Graham, B.; Tunbridge, J.E. Pluralising Pasts. Heritage, Identity and Place in Multicultural Societies; Pluto Press: London, UK; Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, M.L.S.; Carman, J. (Eds.) Heritage Studies: Methods and Approaches, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, G. Time-Relational Process Reading Between Culture and Form: Transformation Process of Privately Owned Industrial Heritage Sites and Actor Roles. Doctoral Dissertation, Polito Repository, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11583/2962240 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Yildiz, G. From Kundura to Cinema: Topological Zeitgeist of Beykoz Kundura in Istanbul; Maggioli: Santarcangelo di Romagna (RN), Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, G. Accessibility of Privately Owned Industrial Heritage Sites: A Multidimensional Analysis of Beykoz Kundura in Istanbul and Leipzig BaumwollSpinnerei. Boll. Della Soc. Geogr. Ital. Ser. 2024, 14, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, S. Leipzig’s Visual Artists as Actors of Urban Change: Articulating the Intersection between Place Attachment, Professional Development and Urban Planning. Master’s Thesis, King’s College London, London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- “From Cotton to Culture.” n.d. Spinnerei. Available online: https://www.spinnerei.de/aktuell (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Chiligaryan, N. Industrial Heritage. Doctoral Dissertation, Bauhous-Universität Weimar, Weimar, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, L.A.; Landau, F. Generating cultural quarters: The temporal embeddedness of relational places. Urban Geogr. 2021, 43, 1610–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novella, E.J. Mental health care in the aftermath of deinstitutionalisation: A retrospective and prospective view. Health Care Analysis 2010, 18, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, G.; Kearns, R. The Afterlives of the Psychiatric Asylum: Recycling Concepts, Sites and Memories, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, S. Cultura architettonica e pratica terapeutica nella progettazione del manicomio di Arezzo. In Asili della Follia. Storie e Pratiche di Liberazione nei Manicomi Toscani; Baioni, M., Setaro, M., Eds.; Pacini Editore: Pisa, Italy, 2017; pp. 106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, G.; Bianchi, F. New strategies on image rebranding and heritage management: Former lunatic asylums, difficult heritage and difficult memories. TÉLÉMATIQUE 2023, 22, 2586–2591. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, G. Community-driven heritage care: Developing an inclusive and sustainable landscape of care for Pionta. Landsc. Res. 2024, 49, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, F. Mind Museums: Former Asylums and the Heritage of Mental Health, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, E. Stages of Memory; Tab Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ada, S. (Ed.) Turkish Cultural Policy Report: A Civil Perspective; Istanbul Bilgi University Press: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy, Y. Islam’s Marriage with Neoliberalism: State Transformation in Turkey; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dinçer, İ. The Impact of Neoliberal Policies on Historic Urban Space: Areas of Urban Renewal in Istanbul. Int. Plan. Stud. 2011, 16, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, A. The Atatürk Cultural Center and AKP’s ‘Mind Shift’ Policy. In Introduction to Cultural Policy in Turkey; Ada, S., Ayça Ince, H., Eds.; Bilgi University Press: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2009; pp. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mieg, H.A.; Oevermann, H.; Noll, H.P. Conserve and Innovate Simultaneously? Good Management of European UNESCO Industrial World Heritage Sites in the Context of Urban and Regional Planning. disP Plan. Rev. 2020, 56, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J. Social-Heritage Innovation Ecosystems. Definition and Case Studies. Rev. PH 2022, 106, 82–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. The Triple Helix: University-Industry-Government Innovation in Action, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Barile, S.; Farioli, F.; Orecchini, F. Strengthening the science–policy–industry interface for progressing towards sustainability: A systems thinking view. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trencher, G.P.; Yarime, M.; Kharrazzi, A. Co-creating sustainability: Cross-sector university collaborations for driving sustainable urban transformations. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dockum, S.; de Wit, L. The Dutch Triple Heritage Helix. A working model for the protection of the landscape. Internet Archaeol. 2020, 54. Available online: https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue54/9/full-text.html (accessed on 1 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Stavrides, S. Common Space: The City as Commons; Zed Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.; Iaione, C. The City as a Commons. 34 Yale L. Policy Rev. 2016, 34, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarino, C.; Negri, A. Praise of the Common: A Conversation on Philosophy and Politics; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S. Public-Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.-E. New Public Management: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, M.J.; Mazza, I. Chapter 2: Cultural heritage: Public decision-making and implementation. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubini, P.; Leone, L.; Forti, L. Role Distribution in Public-Private Partnerships: The Case of Heritage Management in Italy. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2012, 42, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, J.F. Turkish Cultural Policy: In Search of a New Model? In Turkish Cultural Policies in a Global World; Girard, M., Polo, J.F., Scalbert-Yücel, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, J.F.; Türkmen, H. Bulldozer Neo-liberalism in Istanbul: The State-led Construction of Property Markets, and the Displacement of the Urban Poor. Int. Plan. Stud. 2011, 16, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, J.; Evren, Y. Urban Development and Planning in Istanbul. Int. Plan. Stud. 2011, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).