1. Introduction

Miresii Cave [

1] from the village of Rucăr (Argeș County, Romania) is a speleological geomorphosite [

2] of landscape, speophysical, zoospeological (Chiroptera) and paleontological (marine invertebrates) relevance, integrated into some protected natural areas of the Piatra Craiului Mountains and the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor, subunits of relief in the Southern Carpathians (Transylvanian Alps) [

3], Romania. Named also Peștera Fecioarei Cave [

4], it is located in a limestone erosion marker of Mount Posada, on the right slope of the lower gorge (Cheia Mare or Cheia de Jos) of the Dâmbovița River (

Figure 1a), opening on the eastern face of Stâncii Miresei at an absolute altitude of 880 m, relative altitude of 98 m to the cliff top and relative altitude of 158 m to the Dâmbovița riverbed.

The Dâmbovița River, in the Cheii Mari sector, deepens in Jurassic limestones and delimits Mount Posada (1021 m) to the west, Mount Ghimbav (Vf. Colții Ghimbav, 1406.6 m) to the east and Mount Vârtoapele (1434 m) to the south. Cheia Mare of Dâmboviței is included in the central compartment of the low mountain area of the Bran—Dragoslavele corridor and connects the Podu Dâmboviței depression at the northern end, located upstream, with the Rucar at the southwestern end. This key sector became part of the geological and geomorphological nature reserve “Karst area Cheile Dâmbovița—Dâmbovicioara—Brusturet” (RNGG1) before its inclusion in the area of Piatra Craiului National Park (PNPC), by a 1972 decision of the People’s Council of Argeș County, in accordance with Law No. 4/1972 on the management of forests under the direct administration of municipalities [

5]. Later, in accordance with Law no. 5/2000 on the approval of the National Spatial Plan—Section III—Protected Areas [

6], the reserve was included in the strict protection zone of the PNPC by legislating the extension of the original surface of the national park.

In 2007, in accordance with Ministerial Order no. 1964 on the establishment of the regime of protected natural areas of sites of Community importance, as an integral part of the Natura 2000 European ecological network in Romania [

7], a large part of the PNPC territory was integrated into the Natura 2000 European ecological network. Thus, Cheia Mare of Dâmbovița was also included in the protection area of the Site of Community Importance ROSCI 0194 Piatra Craiului.

Considered a geomorphosite, Miresii Cave proves to be a remarkable geotouristic resource, both for its structural values (geomorphologic, aesthetic and ecological), which are often displayed with superiority compared to the other explored and/or investigated cavities in the mountainous area of the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor, and for its functional value related to the potential scientific relevance. The latter, in their turn, certify the first-rate significance of the geomorphosite in the region (together with the Bear Cave in Cheia Mica of Dâmbovița) due to its scientific potential (speophysical, zoospeological and paleontological) and its educational importance as a training resource with a high addressability for the fields of interest, having the attributes of a model with exemplary value. [

8] The presence of an important bat colony and the location of the speosite in the strict protection zone of the PNPC, integrated with other protected natural areas, excludes any form of recreational tourism. Miresii Cave will be able to be exploited as a geotouristic resource, for research and educational purposes only, with access on the basis of a permit issued by the national park administration.

In the wider area of the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor (which also includes the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area), the structural (geomorphological, aesthetic and ecological) and functional (scientific, cultural and economic) values of the geomorphosites, paleontological geosites and archaeospeosites call for research, protection and conservation measures. Further research may cover natural science fields such as geology, physical speleology, zoospeleology, archaeology, etc. Some of the geomorphosites may also be approved for tourism, both for recreation and leisure and for certain cultural activities. As far as tourism with cultural concerns is concerned, the major purpose will be enhanced by emphasizing its educational importance. From a didactic but also practical point of view, geological and geomorphological natural objectives can be integrated into geotouristic circuits with a specialized theme close to international trends in geoturism.

Therefore, we propose that the caving geomorphosite Peștera Miresii, one of the geotouristic objectives within the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area, be included in the thematic geotouristic circuit entitled “The Road of the gorges and caves of the upper Dâmbovița basin” (Dâmbovița Valley axis), integrated with some natural areas protected at national and community level. The association of several caves with diversified scientific relevance and/or didactic importance, located along the Dâmbovița gorges (Mica and Mare), as well as the presence of some key type of valley sectors on the tributaries in the immediate vicinity (Dâmbovicioara, Cheia, Ghimbav Valley and Orăți Valley with the limestone torrent “Cheia Orății”), suggested us the idea of proposing this spectacular geotouristic circuit. The circuit includes, only in the geographical area shown on the map (

Figure 2), the following geotouristic objectives: six linear geosites as morphologic sectors of key type valleys (

Table 1) and seven speleological geosites (

Table 2). To these are added the following: Movila Neamțului (horst) complex geomorphosite with the Oratea (Neamțului) Fortress and “Drumul de Care” (medieval road segment), “Babele Orății” geomorphologic objective (both in the village of Podu Dâmboviței), the thematic somital viewpoint “Vârful Pleașa” (1071.6 m) and three geosites with paleontological relevance [

9] included in the thematic geotouristic circuit “The fossil nests of the Tethys Sea in the Moieciu—Dâmbovicioara—Rucar area”.

The imagined geotouristic circuits included in the wider framework of the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor (on the administrative territories of the communes of Moieciu, Fundata, Dâmbovicioara and Rucar) will be an integral part of two nature reserves, one of which is an existing one (RNGG1, included in the strict protection zone of the Piatra Craiului National Park, category Ib of the International Union for Conservation of Nature), and the second one, we propose to establish (RNGG2—the geological and geomorphological nature reserve “Moieciu—Fundata—Dâmbovicioara—Rucăr geological and geomorphological complex”, category IV IUCN). This new protected natural area will be established in accordance with GEO No. 57 of 20 June 2007, on the regime of protected natural areas, conservation of natural habitats, wild flora and fauna [

12], supplemented with the clarifications of Law No. 49 of 7 April 2011 [

13]. Tourists arriving in the future protected area (RNGG2) will be able to collect information in the field of geotourism from the Dâmbovicioara Tourist Information and Promotion Center (with current information competencies related to cultural, recreational and rural tourism) existing in the locality of Podu Dâmboviței (commune of Dâmbovicioara), established in 2015. The proposed nature reserve would bring together speleological and gorge geomorphosites, geosites of particular paleontological relevance (fossil invertebrates belonging to the Tethys Sea), paleolithic archaeosites and thematic somital belvederes.

The development of geotourism in the area of the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor requires the existence of such thematic geotouristic circuits, with adequate promotion through brochures and information panels. Brochures promoting geosites should fulfill the “6 Fs” rule: familiarization, fascination, functionality, loyalty, formation and fusion [

14].

The geological and geomorphological objectives inventoried in the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area are only a part of all the other geological and geomorphological objectives in the entire geographical area of the depressional corridor mentioned above. We bring to your attention that the proposals for the development of geotourism in the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area are part of our broader concerns, which are included in our doctoral thesis entitled “Bran—Rucar—Dragoslavele corridor. Applied geomorphology study”.

It should be noted that Miresii Cave is not included in the Management Plan of the PNPC and the Natura 2000 Site ROSCI 0194 Piatra Craiului published on 21 February 2020 [

15], and has not been studied so far due to the fact that it is only accessible to explorers with specific climbing skills and equipment. For these reasons, in situ research, including the present study, has acquired a novel character.

The access to the Miresii Cave from the Dâmbovița Valley was opened on a climbing route pythonized in the late 1970s of the last century by a team of the Argeș—Câmpulung Muscel Mountain Rescue Service, according to the report of the Speology Circle “Piatra Craiului” Câmpulung Muscel in the Central Speology Commission Bulletin no. 4, 1980 [

16]. The ascending route has lost its viability, being not recommended more than 40 years after its inauguration. The access from the upper part of Miresei Rock (

Figure 1b) is only recommended for explorers with a thorough knowledge of rock climbing, abseiling and handling technical climbing equipment.

The geographical position of the cave entrance, 45°23′46.75″ N, 25°11′58.10″ E, was marked with GPS via Google Earth mobile phone application on a limestone platform below the portal arch level, approximately right at the cave access, at the nearest available signal.

2. Materials and Methods

Explored since 24 August 1979 by members of the “Cercului Speo Câmpulung” (information plaque at the entrance), the cave has been visited by 3 other teams of climbers (in the summer of 1983, 26 May 2013 and 8 November 2015), but the studies started after our observations in 2020, during three campaigns of drone filming from outside. Our access to the cave in the fall of 2021 allowed us to take speophysical measurements and photographs to decipher morphology and morphogenesis, identify the chiropteran species/species, and assess the conservation status of the colony in its local biotope.

Considering the isolation of the Miresii Cave towards the middle of a slope of about 260 m, almost vertical, in order to reveal the morphology of the facade corresponding to the access portal in the karst system to be investigated and to observe the erosion witness Stânca Miresei Rock seen as a whole, we imagined and undertook three campaigns of drone filming.

The first campaign, on 12 September 2020, was mainly aimed at making observations on the longitudinal lithoclase of the cave’s path, the morphology of the portal and the evaluation of the access possibilities to the entrance of the underground cavity from the Dâmbovița Valley, on a classic climbing route as smooth as possible. In order to achieve the specified objectives, we used a radio-controlled homemade drone, which had the advantage of maneuverability towards the desired altitude and location on the right slope of the Dâmbovița’s Great Pass without encountering problems related to the interruption of the remote-controlled signal. The disadvantages consisted of the quality of the images captured, temporarily blocked by sunlight and partially distorted due to the curvature of the objective lens.

The second campaign, on 20 September 2020, facilitated observations in the upper third of the Miresei Rock to assess the access possibilities to the entrance of the underground cavity from the top of the Miresei Rock. A panoramic image was captured of the eastern façade (

Figure 1b), corresponding to the orientation of the Miresii Cave portal, marked by diaclases that facilitated the penetration of water into the Kimmeridgian–Tithonian limestone mass (Upper Valanginian). To achieve the above objectives, we used the DJI Mavic Air 2 drone (

Figure 3a) launched from 2.8 km away from the Sasului Hill towards the upper part of the Cheii Mari of the Dâmbovița.

The use of drones is of particular importance in the methodological and scientific approach due to the fact that access to the analyzed cave is very difficult, and mapping them starting from the base of the cave entrance would be impossible because the opening is very high and could not be charted by traditional methods. The possibility of exploration from a distance based on the panoramic image made by the drone highlights its tourist potential despite the difficult access and also highlights the need to implement niche tourism with minimum conditions of development to reduce the anthropogenic impact on the geomorphosite analyzed.

The third campaign, on 3 October 2020, was the occasion to make observations on the basin of the mouth of the calcareous torrent deep north of Miresei Cliff, with possible access to the water access to the Miresii Cave.

On 29 October 2021, laser topography of the Iatacul Miresii Cave was possible using the Leica Disto X310 rangefinder (

Figure 3b). The measurements taken were processed using the TopoDroid v.5.1.40 mobile phone application (

Figure 3d), and the longitudinal profile was drawn by computer graphic modeling in the program CorelDRAW Graphics Suite X3 (

Figure 3e) based on the results of the laser measurements. The access and humidity conditions inside the cave led to the use of digital measuring instruments that could be adapted to the specific conditions and, at the same time, meet the final purpose of the mapping. The use of the distomat allowed measurements to be made both on height for mapping the interior of the cave and on height for mapping the ceiling of the cave, which could not be achieved with classical measurement methods. The use of laser-based mapping also increases the accuracy of the measurements by reducing errors and offering the possibility to realize an in situ sketch based on specific software, which was the basis for the final mapping of the geomorphosite.

Exploration of the interior of the Miresii Cave was possible on 31 October 2021. The longitudinal profile and the floor plan of the Miresii Cave were also realized by computer graphic modeling using in situ measured values, averaged by the Bosch DLE 70 Professional rangefinder and 30 m ruler (

Figure 3c).

The morphotectonics of the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area was deciphered by interpreting the information inscribed on the geological maps, scale 1:50,000 [

17,

18], but also based on the information summarized from the specialized geological literature.

The leveling surfaces of the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area were digitized from cartographic supports coming from previous research. The existing information in the geomorphological literature was synthesized in the following sources: geomorphological map of the Rucar—Podu Dâmboviței region [

19] and geomorphological sketch of the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar region [

20]. The geological map of the Bucegi Massif and the Dâmbovicioara corridor, scale 1:50,000 [

17], was useful for mapping the terrace bridges in the Podu Dâmboviței depression. To this last information, we added our contributions regarding the following: the mapping of the lower terrace of the Dâmbovița river within the mentioned depression; the correct spatial positioning on the topographic map, scale 1:25,000 [

21], of the digitized areas in order to correlate them with morphological elements; and the superposition of the digitized areas on the georeferenced geological map, in order to correlate the morphogenetic steps with lithology and some morphotectonic elements.

The digital elevation model (DEM) used for the creation of the topographic database of the Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar geographical area was designed with a spatial resolution of 10 m and a discretization error correction coefficient of 0.5 by interpolating the leveling and drainage network taken from the topographic map, scale 1:25,000, with the equidistance of contour lines equal to 10 m. The interpolation method was implemented in the ArcGIS/ArcMap program, accessible through the Topo to Raster tool, based on the ANUDEM program developed by Michael Hutchinson in 1988, 1989, 1996, 2000 and 2011 [

22].

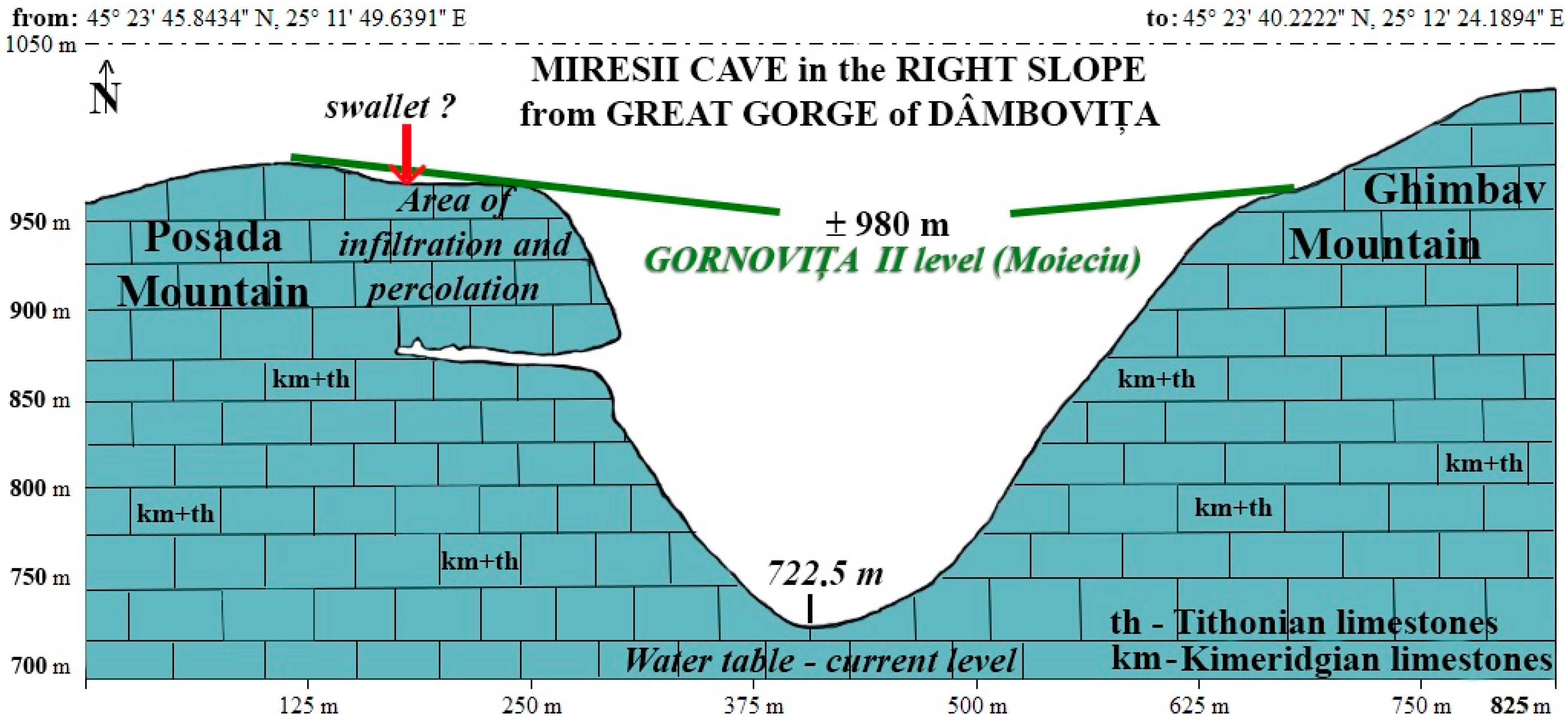

Based on the DEM, a geomorphologic cross-sectional profile was constructed through the Cheia Mare of the Dâmbovița River, approximately on the alignment of the Miresii Cave diaclase, using the dedicated tool Path Profile, available in the Global Mapper v.20.0 application. The rendered profile allowed us to visualize the altitudinal position of the Miresii Cave on the right slope of the Great Dâmbovița Gorge in relation to the position and altitude of the valley shoulders (witnesses of the previous leveling/leveling of the valley relief). The positional correlations (altitudinal and on the map surface) between the Miresii Cave and the leveling surfaces in the Podu Dâmboviței and Rucar depressions, together with morphotectonic and geomorphological observations in the field, allowed us to decipher the morphological individualization of the Miresii Cave in the local and regional geocronomorphological context, in accordance with the chronological separation of the karstification phenomenon by chronological stages.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Morphogenesis of the Miresii Cave

The morphogenesis of the Miresii Cave is closely related to the evolution of the Great Dâmbovița Gorge. The tower-shaped Stânca Miresei rock erosion marker in which the cave was modeled was detached on the right slope of the lower Dâmbovița gorge by the regressive deepening of two limestone streams flanking it to the north and south.

The detailed view of the eastern slope of the limestone marker was made on 12 September 2020 by a radio-controlled drone lifted from the Dâmbovița Valley bed. The images capture a longitudinal diabase in the limestone mass, centered approximately mid-surface of the eastern wall of the Miresei Rock. The fracture, slightly narrowed at the base, gradually widens in elevation to below the rounded vault of the outer portal. The fracture line is further up the steeply sloping (in some sections more than 75°), shrub-vegetated torrential valley (in some sections more than 75°), evident in the upper half of the slope, above the arch of the outer portal (

Figure 1b). The certainty of the extension of the fracture in elevation (towards the somital part of the cliff), along the path of the vallecula above the arcade of the outer portal, is supported by the following: the dihedral plan of the slopes of the valley; the broken arched junction of the walls of the cave vestibule (

Figure 12a) which gives the ogival shape to the inner portal (

Figure 12b); and the morphography in the cross-section of the cave, resembling a house roof arranged in two steeply sloping waters, characteristic of the “Crosnia with Tentacles” hall (

Figure 12c). As an upstream extension of this hall, the “Coral Gallery” is more than 8 m high, and its walls are arranged quasi-parallel. Moreover, the dripping forms, predominantly stalactites but also parietal crusts, are relatively evenly distributed along the entire length of the cave, observations that reveal the direction of infiltration–percolation water towards the lithoclase, as well as its action of dissolving, transporting and depositing calcium carbonate on the erosional forms of the karst system in the ford zone.

The association of numerous pressure–corrosion marmite (or dome) [

27] in the ceiling of the vestibule with the vestibule ceiling is striking, even on the ascending route from the base of the outer portal. These have large diameters (±1 m), mostly arranged in alignments of 2 to 5 microforms (

Figure 8) extending into the interior of the “Tentacle Crosnia” hall. Ceiling marmites, few but large in size, associated with corrosion hieroglyphs [

25], are also present in the last two spacious halls: the “Vestibule of the Throne Hall” and the “Throne Hall”. The presence of the mentioned microforms is a strong argument in favor of the phreatic karstification phenomenon [

28] within the first morphogenetic and morphosculptural stage (Stage I) of the cave.

Field observations have allowed us to accept the hypothesis that, since the Upper Pleistocene, the cave has evolved only in a vadose regime, in which episodes of torrential modeling (Stage II) were manifested. Arguments supporting this hypothesis are related to the following: the shape and dimensions of the access portal (40 m high and 7 m wide at the base), the generalized transversal profile of the cave (steep gabled roof shape), the slope of the floor from downstream to upstream (+10 m–+11 m, over a length of 133 m), a level of lateral erosion identified in the walls of the “Coral Gallery” (at the height of about 1 m), as well as the steeply sloping, regressively, evolved limestone torrential gully in the downstream extension of the cave floor to the outside.

In the Holocene, the predominant geomorphological processes remained that characteristic of karstification: deposition by dripping and gravitational leaching of calcium carbonate contained and precipitated in/from the saturated solution, originating from the infiltration and percolation zone.

The leveling surfaces of the geographical area corresponding to the Podu Dâmboviței and Rucar depressions have been established areal within the dedicated map (

Figure 13) by summing, correlating and synthesizing all the existing information in the geomorphological and geological literature. Relevant contributions related to the deciphering of the geologic and paleogeomorphologic evolution of the Carpathian area corresponding to the Bran—Dragoslavele corridor were made by geographers [

11,

19,

20,

29] and a geologist [

17]. We note that the Braniște Level [

20] is identified only in the southern part of the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor and occurs fragmentarily in the Podu Dâmboviței (the level cuts the sandstones of the Stoichii Hill, being distributed at altitudes of 850–900 m) and Rucăr (the level cuts the marls of the Braniște Hill, being distributed at altitudes of 800–850 m) depressions. Fragments of this level of Middle Pleistocene age [

20] can also be observed along the Dâmbovița mountain valley in the form of valley shoulders framed at altitudes of 810–850 m. This Carpathian valley level [

30] corresponds to the one mapped by Ielenicz at ±820 m in the Dâmbovița Valley [

19] and to the one named by Mihăilescu as the “Râu Târgului surface” [

31], located at the foot of the Iezer Massif, at least between the Argeș and Râul Târgului valleys (820–900 m).

The transverse geomorphologic profile of the valley traced at the location of the cave (

Figure 14) shows its altitudinal position within the right slope of the gorge in relation to the position of the erosion shoulders belonging to the Gornovița II leveling surface (Moieciu level), a morphogenetic step from which the epigenigenic, regressive and fault-faulting deepening of the Paleo-Damboviet torrent with the base level located in the Podu Dâmboviței tectonic depression began [

11].

The tectonic uplift of Mount Posada (horst), concomitant with the fault descent of the Podu Dâmboviței depression (graben), has boosted the process of regressive and deep erosion of the Dâmbovița River. The straight line distance between the vertical fault Pleașa-Nord and the corresponding lithoclase of the Miresii Cave is about 1 km. Thus, the continuous deepening of the Dambouvița in Cheia Mare imposed the local base level to which the torrential valleys, tributary to it, originating in Mount Posada (from the west) and Mount Ghimbav (from the east), have adapted evolutionarily. As a result, the vertical shaping of the Miresii Cave was dictated by the continuous lowering of the local base level of the Dambouvița Dambouvița in the Upper Pleistocene and Holocene. The absolute altitudinal position of the Miresii Cave on the right slope of the Dâmbovița’s Cheii Mari, at ±890 m, allows us to connect it with the Braniște Level, 800–900 m absolute altitude, represented by the fragments mapped within the Podu Dâmboviței and Rucăr depressions. The absolute altitudinal position of the cave, slightly higher than that of the Braniște Level, can be argued by the different local spatial evolution and opposite directions of the tectonic/neotectonic movements that have led to the rise of the Pleașa Mountain horst (with the Miresii Cave) and the descent of the Podu Dâmboviței graben, like the Rucar semi-graben, on proven faults.

The analysis of field observations and the synthesis of all geological and geomorphological data available in the specialized literature, so far, have allowed deciphering the morphological individualization of the Miresii Cave in the local (Podu Dâmboviței—Rucar in the Bran—Dragoslavele corridor) and regional (Iezer Massifs, Piatra Craiului and Leaota Mountains), in accordance with the chronological separation of the karstification phenomenon by chronological stages and in the context of anthropic pressure on the geomorphosite [

38] (

Table 3).

We are of the opinion that the first morphogenetic stage of the initial karst system modeling in a phreatic regime is correlated with the fragmentation stage of the Braniște Level, possibly from the Riss—Würm interglacial period, when the annual amount of liquid precipitation increased, and the flow of the hydrographic network was reinvigorated [

32]. The above-mentioned phenomena were manifested against the background of the opening of the lithoclasis since the Wallachian phase or as a consequence of the neotectonic movements of the Pasadena phase. The relative altitudinal position of the cave in relation to the current bed of the Dâmbovița (about 160 m), the remarkable height of the outer portal, the evolved forms of dripping (“Marea Coloană” and “La Tentacule”), the steep declivity of the limestone torrential gully descending from the cave (directed on the diaclase which conditioned the access of water into the karst system) are evidence of the long evolution of karsts in the vadose karst regime, but which succeeded the phreatic one, as evidenced by the presence of numerous ceiling marmites, dissolving under pressure.

4.2. Ecological Value of Miresii Cave

On the basis of our observations, the few bibliographical sources currently existing [

36] and until further research on the number of individuals in the colonies, we can state that Miresii Cave harbors one of the first two largest colonies of bats of the Rhinolophus ferrumequinum species in Piatra Craiului National Park and the adjacent depressional corridor, with at least 98–100 individuals identified in the hibernating colony in the “Sala Tronului” on 8 November 2015. The other habitat with numerous individuals of the same rhinolophid species is the Bear Cave (Cave of the Surpat Corner), within which photographs taken on 3 October 2020 and 31 October 2020 captured ca. 180 individuals. We note that the Bear Cave is home to two Rhinolophid species: Rhinolophus ferrumequinum and Rhinolophus hipposideros (small horseshoe-nosed bat).

The natural isolation of the cavity, located in the middle of a steep slope, about 260 m high, as well as the stable topoclimate of the last two large halls located at over 100 m depth, are favorable factors of the biotope for the protection of the Chiroptera community in Peștera Miresii. The cave offers ideal conditions of peace and privacy for the perpetuation of the inhabiting species/species. The external environment adjacent to the cave, with relatively unaltered attributes (preserved under the umbrella of the heritage management of the Piatra Craiului National Park and Natura 2000 site), facilitates the protection of foraging habitats for the time being, even though the pollution of the Dâmbovița River with plastic and the shrinking local cattle herd is a constant threat to the reduction in insect populations, as the main food resources for the great horseshoe-nosed bat.

5. Conclusions

Although it belongs to the area of a geological and geomorphological nature reserve since 1972, included in the strict protection zone of the Piatra Craiului National Park (2000) and the “Natura 2000” site ROSCI 0194 Piatra Craiului (2007), the name “Peștera Miresii” is not included in the management plan for the above-mentioned protected natural areas, because it has not been studied so far.

Following the associative analysis of the morphotectonic, morphostructural and local/regional morphogenetic landmarks, with the morphographic and morphometric landmarks determined in the field observation and measurement campaigns, it was possible to conclude that the Miresii Cave evolved through the succession of two distinct morphogenetic stages that imposed different manifestations of the karst phenomenon, each with its characteristic processes and forms: the first stage—karstification in the phreatic (drowned) regime, by the flow of water under pressure, as well as intense chemical corrosion (dissolution); and the second stage—karstification in the vadose regime, by the deepening and widening of the cavity towards the base, conditioned by the free-flowing water level, in torrential episodes, concomitant with the precipitation of calcium carbonate in the forms of dripping and gravitational preleakage. The generation of the forms of pressure corrosion, torrential erosion (and corrosion), chemical precipitation and clastic accumulation occurred along a tectonic stress diaclase, probably opened during block uplift movements in the Wallachian phase and reactivated during neotectonic movements in the Pasadena phase. The vertical evolution of the cave was conditioned by the dimensions of the diaclase that directed the water in the system, in conjunction with the permanent lowering of the local base level imposed by the continuous deepening of the Dâmbovița River in the Jurassic limestone package, along a fault.

Digital mapping using modern methods and techniques is an essential requirement for the digital mapping of the entire cave. The materialization of the proposals made for its introduction in the tourist circuit and protected areas would, first of all, imply its arrangement and providing access to its interior. This would make possible, in the future, monitoring of the cave with modern equipment and its 3D mapping using laser scanners and, last but not least, the VR promotion of the final result both through dedicated applications and online, which are the objectives of future research.

One of the purposes of the present research is to propose to the Scientific Council of the National Park/ROSCI 0194 Piatra Craiului that the general information about the cave be recorded in the management plan and, subsequently, the council to bring to the attention of the authorized and deciding national commissions (in accordance with Law no. 49 of 7 April 2011 for the approval of Government Emergency Ordinance no. 57/2007 on the regime of protected natural areas, conservation of natural habitats, wild flora and fauna) the following of the Miresii Cave:

To be included in protection class B—caves with sectors of national importance (in accordance with Article I, point 64 on the classification of caves or parts of caves according to the criteria of scientific and cultural-educational value);

To be established as a natural monument, IUCN category III (in accordance with Article I, point 68, on the classification of caves or parts of caves according to the purpose and management regime of protected natural areas categories), for the following reasons:

The remarkable landscape value offered by the isolation towards the middle of the steeply sloping eastern wall of the Miresei Rock, with a relative altitude of about 160 m above the Dâmbovița riverbed and about 100 m from the top of the limestone marker. The spectacular opening on the river-facing side of the 40 m-high, naturally sculpted portal of the cave, in an architectural style similar to Gothic, is a striking feature of the landscape, suggested by the ogival form (the entrance to the cave) framed by the arch (the portal is raised outwards). The interior landscape is characterized by the richness of the dripping and gravitational flowing forms, particularly in the last three rooms on the upstream side;

The existence of Upper Jurassic—Lower Cretaceous (Tithonian?) reef-forming fossiliferous deposits evidenced by torrential erosion and selective dissolution on an area of about 1 m2, on the right side of the “Coral Gallery”;

The ecological significance of the first rank, due to the functioning of the cavity as an isolated biotope, ideal for the conservation of one of the first two largest bat communities of the species Rhinolophus ferrumequinum (species of community and national interest), not only in the area of Piatra Craiului National Park but also in the territory of the entire area of the Bran—Dragoslavele Corridor and the Piatra Craiului Mountains. The other community with numerous individuals of this species is the Bear Cave in Cheia Mica in Dâmbovița.

The natural setting famous for the picturesque landscape, but especially the scientific, educational, didactic and cultural value of the geomorphological and geological sites in the area of the Podu Dâmboviței and Rucar depressions, led us to propose the geomorphological caving site Peștera Miresii (with zoospeological, paleontological, ecological, landscape and physical speleological relevance), the set of geotouristic resources of which it is part, which can be exploited along the thematic geotouristic circuit called “The Road of the gorges and caves of the upper Dâmbovița basin”, integrated into the geological and geomorphological nature reserve “The karst area of Cheile Dâmbovița—Dâmbovicioara—Brusturet”, included in the strict protection zone of the Piatra Craiului National Park.