Social Media as Lieux for the Convergence of Collective Trajectories of Holocaust Memory—A Study of Online Users in Germany and Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Holocaust Museums and the Participatory Turn of Digital Memory

3. German Memories of Guilt and the Myth of the Good Italian

4. Methods

- Participants’ interests in several topics related to the Holocaust (e.g., “antisemitism” and “human rights”), 19 items.

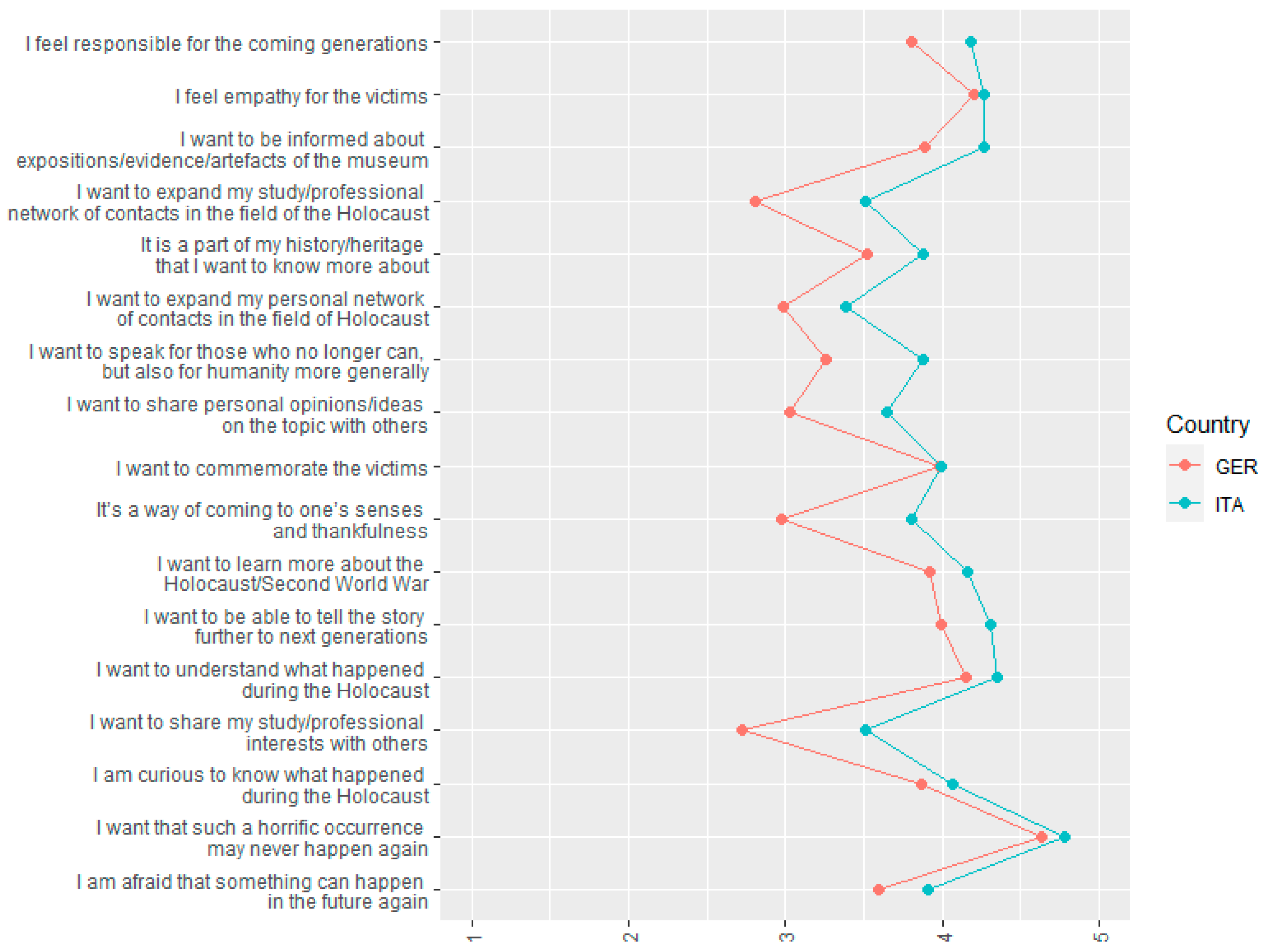

- Personal motivation(s) to follow the museum/memorial page (e.g., “I feel responsible for the coming generations” or “I want to expand my study/professional network of contacts in the field of the Holocaust”), 17 items.

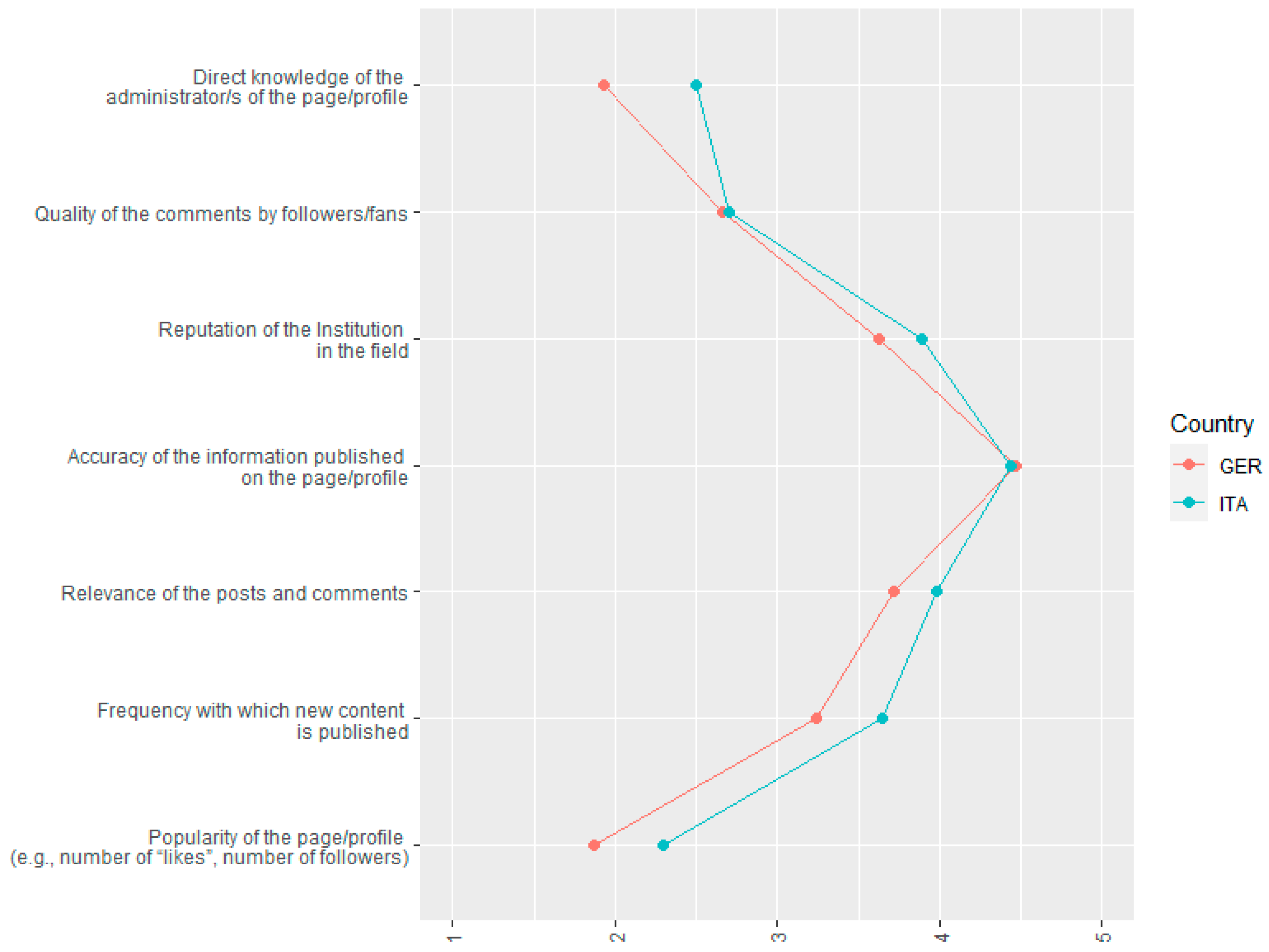

- Motivations to follow a museum/memorial page related to the page (e.g., “Quality of comments by followers/fans” or “Frequency with which new content is published”), 7 items.

- Frequency reported taking specific actions on the page (for example, “Post a comment”, “Mention or tag other users/accounts/pages”, 12 items.

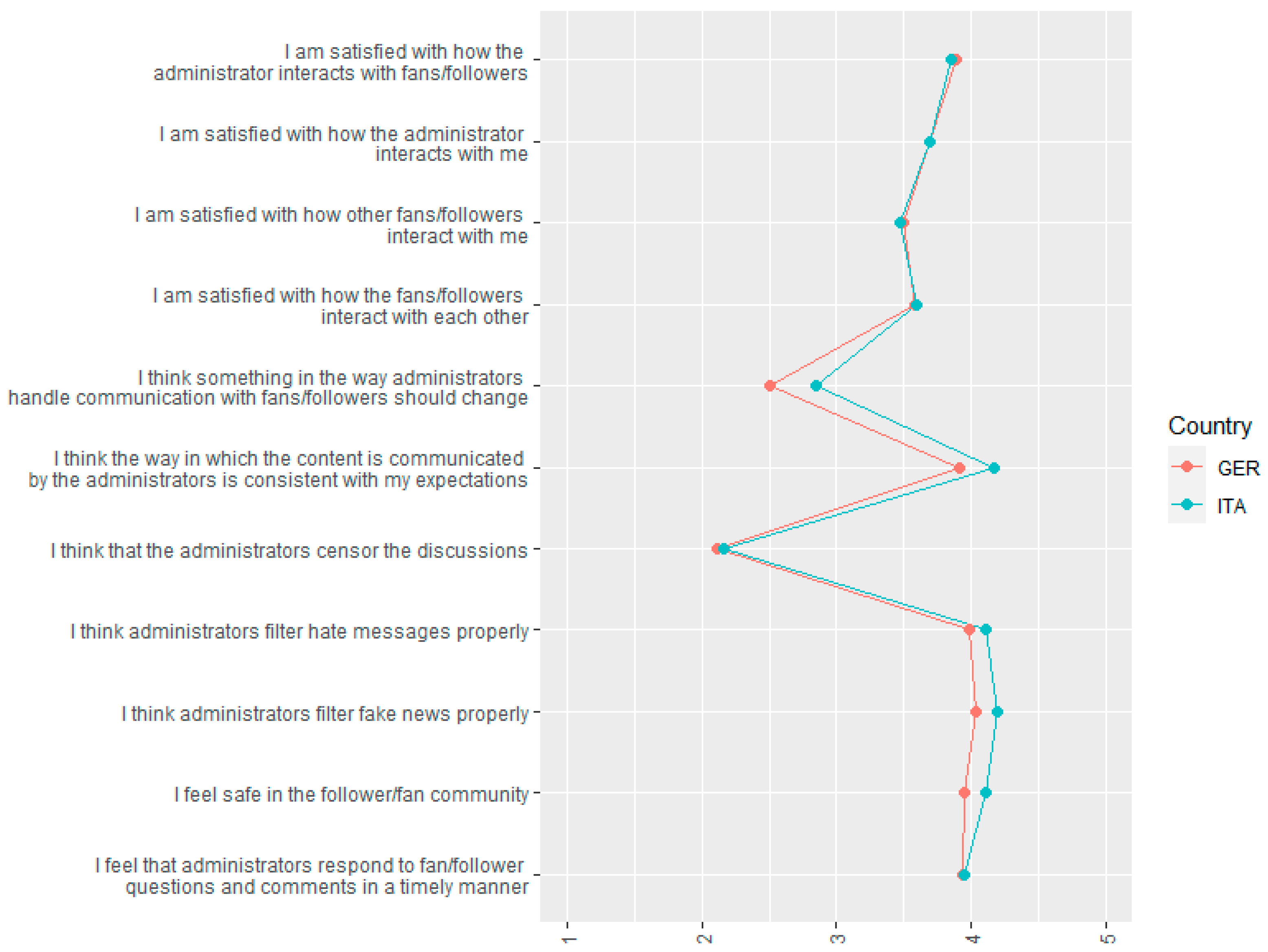

- Lastly, participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with certain aspects of their page (e.g., “I am satisfied with how the administrator interacts with me” or “I feel safe in the followers/fans community”), 11 items.

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Museums and Memorials as Trusted Authorities about the Past

6.2. A High Level of Interest but Low Levels of Interaction

7. Conclusions: Do Social Media Platforms Contribute to a Globalisation of Holocaust Memory?

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A military occupation of half of Italy followed Italy’s surrender and declaration of war against its former Axis partner in September 1943, which marked the beginning of armed resistance to the German occupation as well as the establishment of Benito Mussolini’s puppet state, the Italian Social Republic. Deportations of Italian and foreign Jews to Germany and Poland began at this time. |

References

- Pakier, M.; Stråth, B. A European Memory? In Contested Histories and Politics of Remembrance; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sierp, A. Le politiche della memoria dell’Unione europea. Qualestoria. Riv. Stor. Contemp. 2021, 2, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Subotić, J. Holocaust memory and political legitimacy in contemporary Europe. Holocaust Stud. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, A. Transnational Memory and the Construction of history through Mass Media. In Memory Unbound: Tracing the Dynamics of Memory Studies; Bond., L., Craps, S., Vermeulen, P., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell, I. Reflections on the Transnational Turn in United States History: Theory and Practice. J. Glob. Hist. 2009, 4, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, A. Transnational Memories. Eur. Rev. 2014, 22, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesari, C.; Rigney, A. Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales; De Gruyter: Berlin/ Munchen, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, A. The restless past: An introduction to digital memory and media. In Digital Memory Studies: Media Pasts in Transition; Hoskins, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, A. Memory of the multitude: The end of collective memory. In Digital Memory Studies: Media Pasts in Transition; Hoskins, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Hansen, J.; Hoskins, A.; Reading, A. Save as… Digital Memories; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kansteiner, W. Transnational Holocaust memory, digital culture and the end of reception studies. In The Twentieth Century in European Memory: Transcultural Mediation and Reception; Andersen, T.S., Törnquist-Plewa, B., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 305–343. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D.I.; Schult, T. Revisiting Holocaust Representation in the Post-Witness Era; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wieviorka, A. The Era of the Witness; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T.; Henig, L. I-Memory: Selfies and Self-Witnessing in #uploading_holocaust (2016). In Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research; Walden, V.G., Ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2021; pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst, S. The Era of the User. Testimonies in the Digital Age. Rethink. Hist. 2020, 24, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, A. Memory Ecologies. Mem. Stud. 2016, 9, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Ford, S.; Green, J. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, V.G. Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reading, A. Digital Interactivity in Public Memory Institutions: The Uses of New Technologies in Holocaust Museums. Media Cult. Soc. 2003, 25, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, S. Digital Memory in the Post-Witness Era: How Holocaust Museums Use Social Media as New Memory Ecologies. Information 2021, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T. Commemorating from a Distance: The Digital Transformation of Holocaust Memory in Times of COVID-19. Media Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, V.G. Understanding Holocaust Memory and Education in the Digital Age: Before and After COVID-19. Holocaust Stud. 2022, 28, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erll, A. Cultural Memory Studies: An Introduction. In A Companion to Cultural Memory Studies; Erll, A., Nünning, A., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A. Shadows of Trauma: Memory and the Politics of Postwar Identity; Fordham UP: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Between memory and history: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations 1989, 26, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, V.G. The Memorial Museum in the Digital Age. REFRAME Books. 2022. Available online: https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/the-memorial-museum-in-the-digital-age (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Arnaboldi, M.; Diaz Lema, M.L. The Participatory Turn in Museums: The Online Facet. Poetics 2021, 89, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, S. Digital Holocaust Memory on social media: How Italian Holocaust museums and memorials use digital ecosystems for educational and remembrance practice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 1152–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, S.; Passarelli, M.; Rehm, M. Exploring tensions in Holocaust museums’ modes of commemoration and interaction on social media. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelpšienė, I.; Armakauskaitė, D.; Denisenko, V.; Kirtiklis, K.; Laužikas, R.; Stonytė, R.; Murinienė, L.; Dallas, C. Difficult heritage on social network sites: An integrative review. New Media Soc. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Khan, Z.; Wood, G.; Knight, G. COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keightley, E.; Schlesinger, P. Digital media—Social memory: Remembering in digitally networked times. Media Cult. Soc. 2014, 36, 745–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, A. Seeing red: A political economy of digital memory. Media Cult. Soc. 2014, 36, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, S. Mediatization. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects; Rössler, P., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. La mémoire Collective; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Sodaro, A. Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Museums and the Politics of Past Violence; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.; Sznaider, N. The Holocaust and Memory in The Global Age; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, J.S.; Gassert, P.; Steinweis, A.E. Holocaust Memory in a Globalizing World; Wallstein Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- González-Aguilar, J.M.; Makhortykh, M. Laughing to forget or to remember? Anne Frank memes and mediatization of Holocaust memory. Media Cult. Soc. 2022, 44, 1307–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smale, S. Memory in the Margins: The Connecting and Colliding of Vernacular War Memories. Media War Confl. 2020, 13, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. Is eastern European ‘double genocide’ revisionism reaching museums? Dapim Stud. Holocaust 2016, 30, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cento Bull, A.; Hansen, H.L. On Agonistic Memory. Mem. Stud. 2016, 9, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, M. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, S. The Second World War in the Twenty-First-Century Museum: From Narrative, Memory, and Experience to Experientiality; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Echikson, W. Holocaust Remembrance Project: How European Countries Treat Their Wartime Past. 2019. Available online: https://archive.jpr.org.uk/object-eur216 (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Watson, J. Skirting the abyss: Eastern European space and the limits of German Holocaust memory. Holocaust Stud. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, A. To remember or not to remember? The Germans, National Socialism, and the Holocaust—A typology. Holocaust Stud. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierp, A. Italy’s Struggle with History and the Europeanisation of National Memory. In Erinnerungskulturen in Transnationaler Perspektive; Engel, U., Middell, M., Troebst, S., Eds.; Leipziger Universitätsverlag: Leipzig, Germany, 2012; pp. 212–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fogu, C. Italiani brava gente: The legacy of fascist historical cultural on Italian politics of memory. In The Politics of Memory in Postwar Europe; Lebow, R.N., Kansteiner, W., Fogu, C., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, UK; London, UK, 2006; pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.S.C. The Holocaust in Italian Culture. 1944–2010; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfatti, M. Notes and Reflections on the Italian Law Instituting Remembrance Day. History, Remembrance and the Present. Quest Issues in Contemporary Jewish History. J. Fond. CDEC 2017, 12, 112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, R.K.; Çakmak, E. Understanding visitor’s motivation at sites of death and disaster: The case of former transit camp Westerbork, the Netherlands. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.K.; Nawijn, J.; van Liempt, A.; Gridnevskiy, K. Understanding Dutch visitors’ motivations to concentration camp memorials. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikeler, J.; Silber, H.; Bošnjak, M. A Meta-Analysis of How Country-Level Factors Affect Web Survey Response Rates. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 64, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kist, C. Repairing online spaces for “safe” outreach with older adults. Mus. Soc. Issues 2021, 15, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edy, J. Journalistic use of collective memory. J. Commun. 1999, 49, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Kopelman, S. Remembering COVID-19: Memory, crisis, and social media. Media Cult. Soc. 2022, 44, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henig, L.; Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T. Witnessing Eva Stories: Media Witnessing and Self-Inscription in Social Media Memory. New Media Soc. 2022, 24, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T.; Divon, T. Serious TikTok: Can You Learn About the Holocaust in 60 seconds? MediArXiv 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, B. Resistant Pasts Versus Mnemonic Hegemony: On the Power Relations of Collective Memory. Mem. Stud. 2016, 9, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Contemporary Debates in Holocaust Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Foster SPearce, A.; Pettigrew, A. Holocaust Education. Contemporary Challenges and Controversies; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oztig, L.I. Holocaust museums, Holocaust memorial culture, and individuals: A Constructivist perspective. J. Mod. Jew. Stud. 2023, 22, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelich Biniecki, S.M.; Donley, S. The Righteous Among the Nations of the World: An Exploration of Free-Choice Learning. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wóycicka, Z. Global patterns, local interpretations: New Polish museums dedicated to the rescue of Jews during the Holocaust. Holocaust Stud. 2019, 25, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilles, M.; Winnick, H. Memory, Responsibility, and Transformation: Antiracist Pedagogy, Holocaust Education, and Community Outreach in Transatlantic Perspective. J. Holocaust Res. 2021, 35, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, E. Never forget, never again: Holocaust memorials are reshaping our conception of mass murder, prejudice, and morality by raising awareness and demanding a permanent place in our collective memory. But is that enough to help stave off future genocides? Sci. Spirit 2006, 17, 40+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, C.; Stanley, P. Holocaust heritage digilantism on Instagram. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansteiner, W. The Holocaust in the 21st century: Digital anxiety, transnational cosmopolitanism, and never again genocide without memory. In Digital Memory Studies: Media Pasts in Transition; Hoskins, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 110–140. [Google Scholar]

- Porat, D. Is the Holocaust a Unique Historical Event? A Debate between Two Pillars of Holocaust Research and its Impact on the Study of Antisemitism. In Comprehending Antisemitism through the Ages: A Historical Perspective; Lange, A., Mayerhofer, K., Porat, D., Schiffman, L.H., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, A.S.; Maor, R.; McGregor, I.M.; Mills, G.; Schweber, S.; Stoddard, J.; Hicks, D. Holocaust education in transition from live to virtual survivor testimony: Pedagogical and ethical dilemmas. Holocaust Stud. 2022, 28, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Germany | Italy | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facebook page | 117 (46.1%) | 222 (80.4%) | 339 (64.0%) |

| Twitter profile | 35 (13.8%) | 8 (2.9%) | 43 (8.1%) |

| Instagram profile | 99 (39.0%) | 7 (2.5%) | 106 (20.0%) |

| YouTube channel | 3 (1.2%) | 39 (14.1%) | 42 (7.9%) |

| Total | 254 (100.00%) | 276 (100.00%) | 530 (100.0%) |

| Germany | Italy | TOT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 144 (56.7%) | 208 (75.4%) | 352 (66.4%) |

| Male | 101 (39.8%) | 65 (23.6%) | 166 (31.3%) | |

| Other/Prefer not to say | 9 (3.5%) | 3 (1.1%) | 12 (2.3%) | |

| Higher education degree | Yes | 172 (67.7%) | 202 (73.2%) | 374 (70.6%) |

| No | 82 (32.3%) | 74 (26.8%) | 156 (29.4%) | |

| Position | Teacher/Educator | 13 (5.1%) | 85 (30.8%) | 98 (18.5%) |

| Retired | 15 (5.9%) | 52 (18.8%) | 67 (12.6%) | |

| Clerical staff | 18 (7.1%) | 36 (13.0%) | 54 (10.2%) | |

| Scholar/Academic/Cultural operator | 65 (25.6%) | 28 (10.1%) | 93 (17.5%) | |

| Self-employed | 21 (8.3%) | 25 (9.1%) | 46 (8.7%) | |

| Student | 31 (12.2%) | 11 (4.0%) | 42 (7.9%) | |

| Other | 91 (35.8) | 39 (14.1%) | 130 (24.5%) | |

| Educational and informal experiences related to the Holocaust | Teaching | 210 (82.7%) | 191 (69.2%) | 401 (75.7%) |

| Organization | 183 (72.0%) | 180 (65.2%) | 363 (68.5%) | |

| Planning | 164 (64.6%) | 180 (65.2%) | 344 (64.9%) | |

| Participation | 225 (88.6%) | 232 (84.1%) | 457 (86.2%) | |

| Visits to memory sites | 246 (96.9%) | 259 (93.8%) | 505 (95.3%) | |

| Teaching | 210 (82.7%) | 191 (69.2%) | 401 (75.7%) |

| Category | Item | Germany (M ± SD) | Italy (M ± SD) | t-Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest | Antisemitism | 3.95 ± 0.67 | 4.28 ± 0.73 | t (502.56) = 5.4, p < 0.001 *** |

| Cultural heritage | 3.68 ± 0.77 | 4.25 ± 0.72 | t (485.33) = 8.63, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Dark tourism | 3.94 ± 0.72 | 4.13 ± 0.92 | t (494.94) = 2.69, p = 0.007 ** | |

| Fascism and other Nazi accomplices’ ideology | 3.98 ± 0.71 | 4.10 ± 0.89 | t (497.16) = 1.7, p = 0.089 | |

| Heritage from the Holocaust: Hope, Faith and Resilience | 3.79 ± 0.85 | 4.10 ± 0.88 | t (497.1) = 3.94, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Historical events | 4.03 ± 0.72 | 4.31 ± 0.71 | t (493.14) = 4.51, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Holocaust denial and distortion | 3.84 ± 0.85 | 4.15 ± 0.91 | t (501.13) = 4.01, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Human rights | 3.91 ± 0.81 | 4.36 ± 0.75 | t (484.89) = 6.42, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Jewish culture | 3.61 ± 0.81 | 4.07 ± 0.98 | t (499.95) = 5.75, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Nazi ideology | 3.65 ± 0.84 | 3.50 ± 1.06 | t (496.7) = 1.7, p = 0.091 | |

| Other genocides | 3.37 ± 0.90 | 3.79 ± 0.87 | t (491.79) = 5.31, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Personal stories of victims or survivors | 4.21 ± 0.73 | 4.23 ± 0.84 | t (501.87) = 0.36, p = 0.717 | |

| Racism | 3.88 ± 0.78 | 4.01 ± 0.91 | t (501.32) = 1.77, p = 0.077 | |

| Refugees and immigration | 3.59 ± 0.97 | 3.88 ± 0.91 | t (484.93) = 3.48, p = 0.001 ** | |

| Remembrance and commemoration | 4.14 ± 0.77 | 4.08 ± 0.84 | t (501.3) = 0.73, p = 0.465 | |

| The Righteous among the Nations | 3.47 ± 0.94 | 4.09 ± 0.88 | t (483.14) = 7.59, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Totalitarian regimes | 3.35 ± 0.94 | 3.83 ± 0.93 | t (491.58) = 5.76, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Trauma psychology | 3.26 ± 1.16 | 3.75 ± 1.05 | t (479.05) = 4.95, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Wars and conflicts | 3.14 ± 0.96 | 3.57 ± 0.95 | t (492.95) = 5.06, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Personal motivation | I feel responsible for the coming generations | 3.81 ± 0.93 | 4.18 ± 0.77 | t (405.41) = 4.59, p < 0.001 *** |

| I feel empathy for the victims | 4.21 ± 0.73 | 4.27 ± 0.73 | t (435.92) = 0.93, p = 0.354 | |

| I want to be informed about expositions/evidence/artefacts of the museum | 3.89 ± 0.77 | 4.26 ± 0.71 | t (425.06) = 5.36, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I want to expand my study/professional network of contacts in the field of the Holocaust | 2.81 ± 1.41 | 3.51 ± 1.17 | t (405.35) = 5.67, p < 0.001 *** | |

| It is a part of my history/heritage that I want to know more about | 3.52 ± 1.17 | 3.87 ± 1.10 | t (428.72) = 3.3, p = 0.001 ** | |

| I want to expand my personal network of contacts in the field of Holocaust | 2.98 ± 1.26 | 3.38 ± 1.14 | t (423.07) = 3.52, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I want to speak for those who no longer can, but also for humanity more generally | 3.26 ± 1.19 | 3.87 ± 1.03 | t (415.66) = 5.76, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I want to share personal opinions/ideas on the topic with others | 3.02 ± 1.09 | 3.65 ± 0.96 | t (416.27) = 6.39, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I want to commemorate the victims | 3.98 ± 0.82 | 3.99 ± 0.90 | t (443.42) = 0.13, p = 0.895 | |

| It’s a way of coming to one’s senses and thankfulness | 2.97 ± 1.30 | 3.81 ± 1.08 | t (404.2) = 7.31, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I want to learn more about the Holocaust/Second World War | 3.92 ± 0.79 | 4.16 ± 0.81 | t (440.14) = 3.12, p = 0.002 * | |

| I want to be able to tell the story further to next generations | 3.99 ± 0.89 | 4.31 ± 0.82 | t (424.13) = 3.95, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I want to understand what happened during the Holocaust | 4.15 ± 0.74 | 4.35 ± 0.72 | t (434.58) = 2.98, p = 0.003 * | |

| I want to share my study/professional interests with others | 2.73 ± 1.41 | 3.51 ± 1.19 | t (406.87) = 6.3, p < 0.001 *** | |

| I am curious to know what happened during the Holocaust | 3.87 ± 0.86 | 4.06 ± 0.89 | t (440.61) = 2.32, p = 0.021 * | |

| I want that such a horrific occurrence may never happen again | 4.63 ± 0.64 | 4.78 ± 0.56 | t (416.15) = 2.52, p = 0.012 * | |

| I am afraid that something can happen in the future again | 3.59 ± 1.02 | 3.91 ± 0.98 | t (431.86) = 3.29, p = 0.001 *** | |

| Motivations related to the page | Direct knowledge of the administrator/s of the page/profile | 1.93 ± 1.14 | 2.50 ± 1.23 | t (408.38) = 4.88, p < 0.001 *** |

| Quality of the comments by followers/fans | 2.66 ± 1.08 | 2.70 ± 1.02 | t (397.72) = 0.39, p = 0.695 | |

| Reputation of the Institution in the field | 3.63 ± 0.97 | 3.89 ± 0.92 | t (397.04) = 2.78, p = 0.006 ** | |

| Accuracy of the information published on the page/profile | 4.47 ± 0.64 | 4.44 ± 0.72 | t (408.88) = 0.4, p = 0.692 | |

| Relevance of the posts and comments | 3.72 ± 0.79 | 3.98 ± 0.94 | t (407.15) = 3, p = 0.003 ** | |

| Frequency with which new content is published | 3.24 ± 0.84 | 3.65 ± 0.93 | t (408.93) = 4.6, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Popularity of the page/profile (e.g., number of “likes”, number of followers) | 1.87 ± 1.02 | 2.30 ± 1.11 | t (408.55) = 4.12, p < 0.001 *** | |

| Actions | Like content | 3.42 ± 1.16 | 3.46 ± 1.21 | t (402.76) = 0.33, p = 0.743 |

| Like comments | 2.31 ± 1.08 | 2.67 ± 1.21 | t (403.99) = 3.14, p = 0.002 ** | |

| Post a comment | 1.98 ± 0.90 | 2.03 ± 0.81 | t (382.84) = 0.63, p = 0.532 | |

| Reply to a comment | 1.90 ± 0.92 | 1.94 ± 0.83 | t (380.97) = 0.46, p = 0.647 | |

| Reply to content/comment with new content (e.g., comment with text/photo/video/link) | 1.69 ± 0.89 | 1.75 ± 0.80 | t (383.03) = 0.7, p = 0.486 | |

| Post new content (e.g., text, photo, video) | 1.71 ± 1.05 | 1.60 ± 0.80 | t (343.53) = 1.15, p = 0.249 | |

| Retweet/share content | 2.64 ± 1.29 | 2.55 ± 1.16 | t (379.76) = 0.79, p = 0.431 | |

| Mention or tag other users/accounts/pages | 1.84 ± 1.02 | 1.91 ± 1.01 | t (395.25) = 0.7, p = 0.483 | |

| Use direct or private message to interact with other users | 1.64 ± 0.99 | 1.75 ± 0.97 | t (389.83) = 1.13, p = 0.259 | |

| Use direct or private message to interact with the administrators | 1.38 ± 0.70 | 1.61 ± 0.77 | t (398.21) = 3.1, p = 0.002 ** | |

| Use page/profile hashtags in my posts | 2.04 ± 1.22 | 1.73 ± 0.96 | t (354.09) = 2.83, p = 0.005 ** | |

| Participate to donation campaign organized by the page/profile | 1.61 ± 0.75 | 1.88 ± 0.92 | t (381.38) = 3.18, p = 0.002 ** | |

| Satisfaction | I am satisfied with how the administrator interacts with fans/followers | 3.89 ± 0.81 | 3.86 ± 0.88 | t (333.3) = 0.36, p = 0.716 |

| I am satisfied with how the administrator interacts with me | 3.70 ± 0.81 | 3.69 ± 0.88 | t (266.58) = 0.09, p = 0.927 | |

| I am satisfied with how other fans/followers interact with me | 3.50 ± 0.70 | 3.48 ± 0.72 | t (265.69) = 0.29, p = 0.775 | |

| I am satisfied with how the fans/followers interact with each other | 3.59 ± 0.78 | 3.59 ± 0.76 | t (308.24) = 0.06, p = 0.955 | |

| I think something in the way administrators handle communication with fans/followers should change | 2.50 ± 0.93 | 2.85 ± 0.93 | t (294.27) = 3.36, p = 0.001 ** | |

| I think the way in which the content is communicated by the administrators is consistent with my expectations | 3.92 ± 0.73 | 4.17 ± 0.87 | t (357.48) = 2.98, p = 0.003 ** | |

| I think that the administrators censor the discussions | 2.11 ± 1.03 | 2.16 ± 1.11 | t (334.92) = 0.41, p = 0.685 | |

| I think administrators filter hate messages properly | 3.99 ± 0.80 | 4.11 ± 0.93 | t (353.97) = 1.33, p = 0.183 | |

| I think administrators filter fake news properly | 4.03 ± 0.76 | 4.20 ± 0.96 | t (355.9) = 1.89, p = 0.060 | |

| I feel safe in the follower/fan community | 3.95 ± 0.77 | 4.10 ± 0.90 | t (343.14) = 1.67, p = 0.096 | |

| I feel that administrators respond to fan/follower questions and comments in a timely manner | 3.94 ± 0.75 | 3.95 ± 0.87 | t (329.18) = 0.09, p = 0.931 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manca, S.; Passarelli, M. Social Media as Lieux for the Convergence of Collective Trajectories of Holocaust Memory—A Study of Online Users in Germany and Italy. Heritage 2023, 6, 6377-6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090334

Manca S, Passarelli M. Social Media as Lieux for the Convergence of Collective Trajectories of Holocaust Memory—A Study of Online Users in Germany and Italy. Heritage. 2023; 6(9):6377-6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090334

Chicago/Turabian StyleManca, Stefania, and Marcello Passarelli. 2023. "Social Media as Lieux for the Convergence of Collective Trajectories of Holocaust Memory—A Study of Online Users in Germany and Italy" Heritage 6, no. 9: 6377-6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090334

APA StyleManca, S., & Passarelli, M. (2023). Social Media as Lieux for the Convergence of Collective Trajectories of Holocaust Memory—A Study of Online Users in Germany and Italy. Heritage, 6(9), 6377-6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090334