Abstract

While the community of Australian planning professionals is familiar with the identification, interpretation and application of heritage conservation areas, this is not a concept that is familiar to the general public. Yet, none of the official publications issued by the New South Wales state heritage authorities provide a definition of the purpose of heritage conservation areas that goes beyond the declaring them to be a spatially bounded area containing heritage items. It is left to the local planning authorities to provide their own interpretations and definitions. This paper provides a systematic review of the definitions contained in NSW local heritage studies and planning documents. It presents the first ever comprehensive definition of the purpose of heritage conservation areas as well as of the nature and characteristics of an area’s constituent, contributory or detracting components. Based on this, the paper then explores the role of heritage conservation areas as part of the public heritage domain focussing on the importance of isovists and commensurate curtilages when discussing permissible alterations and new developments.

1. Introduction

In the Australian setting, the management of tangible cultural heritage is shared between the Commonwealth government at the national level and the governments of the six states (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia) and the two territories (Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory). According to Australia’s constitution, land management and planning controls (and thus heritage management) reside with the states, unless related to international conventions, Indigenous cultural heritage, or assets (buildings, parcels of land) either owned by or made subject to the protection by the Commonwealth government. State governments devolved the management of heritage assets of local heritage significance to the relevant local government authority, while retaining decision control over heritage assets deemed to be of state-wide or national heritage significance.

The New South Wales (NSW) planning literature regularly refers to Heritage Conservation Areas [1,2,3], with the term being commonplace, among others, in local environmental plans and development control plans [4]. Thus, when presenting the general public with the concept of heritage conservation areas as part of community-based heritage studies, it is important to be able to succinctly describe and define what the conceptual construct of a heritage conservation area entails.

While conducting a heritage review for Albury City (NSW, Australia), it became obvious, however, that no such definition is currently provided by the NSW Heritage Office or other government instrumentalities. Rather, it appeared that every council, if they chose to do so, proffered their own descriptions. Statutory instruments, such as Local Environmental Plans, commonly based on standard provisions as formulated by the NSW Department of Planning, present a legal framework that defines a heritage conservation area in terms of a spatial envelope encompassing items of heritage value, but they do not describe the nature and function of a heritage conservation area. Development Control Plans provide detailed guidance on permissible actions within identified heritage conservation areas. They also may include descriptions of specific heritage conservation areas and their characteristics and cultural heritage significance, but they do not describe or define the nature of a significant area at a general level either.

It would appear that everybody is supposed to know what a heritage conservation area is, albeit without being given formal guidance to understand this concept. Clearly, that state of affairs is far from helpful. The aim of this paper is to trace the historic trajectory of the development of heritage conservation areas in Australia with special reference to NSW and, based on this, carry out a systematic survey of all local government websites and documents published online, in order to explore the definitions used to describe the nature of heritage conservation areas. On the basis of this review, the paper will present a consolidated definition of a heritage conservation area which will lead into a discussion of criteria suitable for the evaluation of the constituent components of a given heritage conservation area. The paper concludes with a discussion of management approaches in particular view lines, outlining avenues for possible enhancement.

2. Historic Background of Heritage Conservation Areas with Special Reference to NSW

The 1945 amendments to the NSW Local Government Act of 1919 [5] gave local councils the power to develop planning schemes that could include, inter alia, “the preservation of places or objects of historical or scientific interest or natural beauty or advantage” [5]. This extended to individual properties only, with the first individual listings occurring in 1957 [6]. The emphasis of protection remained at the individual property level, as perceived by both local governments and the union movement that were active in heritage preservation during the period of the green bans in Sydney in the 1960s and 1970s [7,8].

Internationally, the first country to establish heritage conservation areas was France, which in 1962 passed “[l]egislation on the protection of the historical and aesthetic heritage of France and to facilitate the restoration of real estate” (Législation sur la protection du patrimoine historique et esthétique de la France et tendant à faciliter la restauration immobilièré) [9,10]. In 1966, the US National Historic Preservation Act established the National Register of Historic Places [11], which included the category of ‘historic districts,’ which were defined as “a geographically definable area, urban or rural, possessing a significant concentration, linkage, or continuity of sites, buildings, structures, or objects united by past events or aesthetically by plan or physical development. A district may also comprise individual elements separated geographically but linked by association or history” [12,13]. Individual states soon followed suit [14,15,16]. In the United Kingdom, the Civic Amenities Act of 1967 introduced the concept of heritage conservation areas into planning law, defining these as “areas of special architectural or historical interest the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance” [17].

The Australian conservation movement took up these ideas. Conservation areas were initially perceived to be rural townships which had seen little detracting development, such as Berrima [18]. The National Trust of NSW (founded in 1945) pioneered the concept of an urban conservation area as early as 1972 when it set up the Urban Conservation Committee. It was tasked with “making recommendations to the National Trust Council on which areas or parts of areas should be classified” as worthy on National Trust recognition [19,20] focusing on the ‘character’ of an area, such as the Argyle Place in the Rocks area of Sydney [18]. The National Trust defined an ‘urban conservation area’ as “an area of importance within whose boundaries controls are necessary to retain and enhance its character” [19]. At the time, the meaning of character in an urban setting was commonly understood, yet not defined [21]. As noted by Russell, much of the emphasis was on the scenic and aesthetic contributions of the buildings to the streetscape [22], and less on aspects of architectural and historic cohesiveness or ‘sense of place.’ Conservation areas were considered by most local government-focussed heritage studies that were being carried out by the National Trust in the early to mid-1970s [23,24]. Some of the National Trust-inscribed ‘conservation areas’ in NSW, such as Hunter’s Hill in Sydney in 1974 [25,26], were later listed on the Commonwealth-managed Register of the National Estate [27], which had been established in 1975 [28].

On an international level, UNESCO issued a “Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas” in 1976, which defined “historic and architectural (including vernacular) areas [as] any groups of buildings, structures and open spaces including archaeological and palaeontological sites, constituting human settlements in an urban or rural environment, the cohesion and value of which, from the archaeological, architectural, prehistoric, historic, aesthetic or sociocultural point of view are recognized. Among these ‘areas’, which are very varied in nature, it is possible to distinguish the following in particular: prehistoric sites, historic towns, old urban quarters, villages and hamlets as well as homogeneous monumental groups, it being understood that the latter should as a rule be carefully preserved unchanged” [29]. Possibly because it was placed on a much broader footing than the concepts of heritage conservation areas then current in Australia, the UNESCO recommendation does not seem to have gained much traction in NSW or any of the other Australian states—at least as far as formal references to the document’s recommendations are concerned. An exception was the National Trust in Victoria, which declared the historic core of the gold mining town of Maldon to be a ‘notable town’ as early as 1965 (the only time the National Trust used such a classification) [30].

That declaration, and the subsequent conservation planning exercises, set in train amendments to the Victorian Planning legislation (the Town and Country Planning Act), which provided protection for “area[s] specified as being of special significance” [31]). Victoria then followed through being the first state in Australia to enact heritage legislation, but that act focussed on stand-alone buildings (Historic Buildings Act of 1974 [32]). The subsequent, revised acts of 1995 and 2017 also do not address heritage conservation areas [33,34].

The South Australian Heritage Act of 1978 defined State Heritage Areas as “an area of land is part of the environmental, social or cultural heritage of the State; and that the area is of significant aesthetic, architectural, historical, cultural, archaeological, technological or scientific interest” [35].

In NSW, the passage of the Heritage Act (NSW) 1977 established a formal regime for the identification and protection of places of environmental heritage in the state [36]. That act defined a ‘heritage precinct’ as “a precinct for the time being designated as a heritage precinct in an interim conservation order” and a ‘precinct’ itself as “(a) an area; (b) a part of an area; or (c) any other part of the State, containing buildings, works, relics or places, the majority of which are items of the environmental heritage” [36]. While NSW local government authorities had been given planning powers to manage heritage at the local level following the passage of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act (NSW) 1979, uptake was slow and selective until the NSW government issued a directive to that effect in 1985 [6,37].

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw an increasing understanding by the heritage profession to consider historic properties not in isolation, but as part of their setting, and to view groups of buildings as parts of conservation neighbourhoods and districts [6], with an increasing emphasis on sense of place. In NSW and Victoria, this found expression in the creation of numerous conservation areas. By the time the Register of the National Estate was disestablished in 2007 [38], a total of 134 conservation areas had been registered at a national level in all states and territories (with the majority in NSW, 33.6%, and Victoria, 27.6%), with another 158 conservation areas having been placed on the indicative list (NSW, 54.%; Victoria, 20.2%) [39]. Frequently, the creation of heritage conservation areas referred to an area’s ‘character,’ which continued to be not well described and open to interpretation, both in relation to the concept itself as well as the specifics of the area [21]. The growth in heritage conservation areas seems to have caused some disquiet among bureaucrats, at least in South Australia, who were concerned that the concept was used by residents as a tool to prevent development in their area [40] in a similar fashion as it had been implemented overseas [41]. The risk, as they saw it, was that heritage values and amenity values might become commingled.

The International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) formulated a Charter for the ‘Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas’ (Washington Charter) in 1987, which noted that “[i]n order to be most effective, the conservation of historic towns and other historic urban areas should be an integral part of coherent policies of economic and social development and of urban and regional planning at every level” [42].

The charter addressed conservation areas both on a whole-of-town and a district level, commonly a town’s historic urban core [43]. The Washington Charter found little traction in Australian heritage planning circles, largely because much of the management of heritage had been devolved from the State to the local government level, where local and often parochial interests prevailed over international concepts and charters.

The revision of the NSW Heritage Act in 1987 provided for new definitions. Among these was a revised definition for a ‘heritage precinct’, which was to mean “an area which contains one or more buildings, works, relics or places which is an item or which are items of the environmental heritage; and has a character or appearance that it is desirable to conserve”, whereby ‘environmental heritage’ meant “those buildings, works, relics or places of historic, scientific, cultural, social, archaeological, architectural, natural or aesthetic significance for the State” [44]. The 1987 revision introduced the term ‘character’ into NSW heritage planning law without defining what ‘character’ entailed. That notwithstanding, the term was readily taken up local planning instruments.

In 1996, the NSW Heritage Office published the “Heritage Manual” which contained a section on Conservation Areas and augmented it with a specific guide on managing change in conservation areas [45]. Both the manual and the guide have since been discontinued. The ‘Guide on managing change in Conservation Areas’ provided a ‘definitions’ section that described and referenced various approaches by the then Register of the National Estate (‘heritage area of natural or cultural value’) and the National Trust of NSW (‘urban conservation area’). In their discussion, the authors noted that “[a] heritage conservation area is more than a collection of individual heritage items. It is an area in which the historical origins and relationships between the various elements create a sense of place that is worth keeping” [45].

2.1. Additional Definitions Provided by the NSW Heritage Office

While the Heritage Act 1977 defined ‘heritage precincts’ [36], these were removed two years later when the act was amended [46] to bring it into line with the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act [47]. Neither ‘heritage precinct’ nor the term ‘heritage conservation area’ is mentioned in subsequent amendments of the NSW Heritage Act in 1996, 1998, 2009 or 2011 [48,49,50].

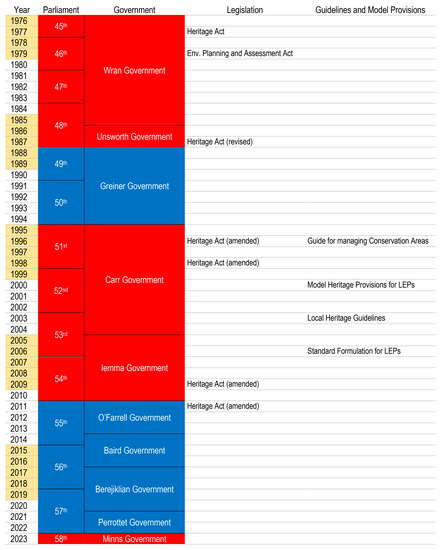

In terms of definitions, the NSW Heritage Office issued a set of Model Heritage Provisions for Local Environmental Plans in 1995 which used the following definition: “‘Heritage conservation areas’ can include buildings, works, relics, trees and places which contribute to the heritage significance of the area. Heritage items may be separately located within the land covered by the heritage conservation area. Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal potential archaeological sites may also be included” [51]. It should be noted that the reference to ‘character’ had been omitted. By the end of the millennium, the political realities had become more conservative, irrespective of political parties (Figure 1) with a concomitant emphasis on economic and infrastructure development at the expense of heritage protection.

Figure 1.

Chronology of heritage legislation in NSW (Labour Governments shown in red; Liberal/National Governments shown in blue).

In 2000, the NSW Heritage Office issued a new set of Model Heritage Provisions using the following very generic definition: “heritage conservation area means an area of land that is shown [insert how it is shown, for example, edged heavy black] on the map marked “...........” and includes buildings, works, archaeological sites, trees and places and situated on or within the land” [52].

The same formulation was added to the Local Government Heritage Guidelines of 2002 [53]. The provision of the state-wide standard formulations for Local Environmental Plans 2006 was as follows: “heritage conservation area means: (a) an area of land that is shown as a heritage conservation area on the Heritage Map (including any heritage items situated on or within that conservation area), or (b) a place of Aboriginal heritage significance shown on the Heritage Map” [54]. In the 2008 amendments to the dictionary section, the definition was altered to “heritage conservation area means an area of land of heritage significance—(a) shown on the Heritage Map as a heritage conservation area, and (b) the location and nature of which is described in Schedule 5, and includes any heritage items situated on or within that area” [55]. The protective mechanisms that apply to the heritage conservation areas are spelled out in the respective development control plans.

These definitions circumscribe the spatial parameters of heritage conservation areas, as well as the nature of their constituent materials (“buildings, works, archaeological sites, trees and places and situated on or within the land”) but do not explain their characteristics, nor the function such an area fulfils in the heritage system of the state. Indeed, while the fourth, and most recent update, the “Guide to the Heritage System” published by the NSW Heritage Office makes reference to Heritage Conservation Areas, it once more does not provide any further definitions. The same applies to pertinent guidelines such as “Assessing heritage significance” [56] and the “Local Government Heritage Guidelines”[53]. Likewise, the National Trust of NSW, on its current website, has reverted to the legalistic default position, by stating that “[a] heritage conservation area is a locality defined by a Council in its Local Environmental Plan (LEP) as having cultural significance” [57]. The Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter, although the guiding instrument for heritage practice in Australia, is silent on the matter [58].

2.2. Definitions by Other Bodies in NSW

From 2005 until their repeal as directed by the NSW State government [59], the Blue Mountains council maintained a specific concept of spatial heritage conservation: “Period Housing Areas”. These were defined as “areas within the towns and villages of the Blue Mountains that have a high proportion of early (19th and early 20th Century) housing with streetscapes displaying a traditional character that contributes to the heritage significance of that town or village” [60] and where the main protections were to “limit the demolition of historic or older dwellings, and maintain streetscape values and local character when development occurs” [59].

3. Methodology

This paper follows the standard procedures for rapid reviews carried out by a single assessor [61,62]. Sought were definitions for heritage conservation areas in general and specific definitions, whether individual constituent components were contributing to or detracting from heritage conservation areas.

3.1. Sampling Frame

The search was carried out on 17 April 2023. The sampling frame was composed of a systematic Google search of NSW local government websites and publications hosted on NSW local government services (restricted to these by using the “site:xyz” coding). The following two search logics were applied:

- A.

- “Heritage Conservation Area” + LGA + site:nsw.gov.au

- B.

- [“Development Control Plan”|DCP] + “Contributory building” + site:nsw.gov.au

The search term for the LGA used the geographic term (e.g., Albury, Cessnock, etc.) but omitted administrative classifiers such as ‘City of,’ ‘Shire’ or ‘Council.’

3.2. Categories for Exclusion

For search logic A, the first 50 results for each search were screened. Local Environmental Plans were excluded because their text is mandated to be based on the standard planning instrument [55]. For search logic B, all results were screened.

4. Results

4.1. Definitions of Heritage Conservation Areas

Only one quarter of the councils (24.4%) provided a description or definition of what a heritage conservation area may entail that went beyond the standard formulation provided in the local environmental plan (see Supplementary Data, Section S1).

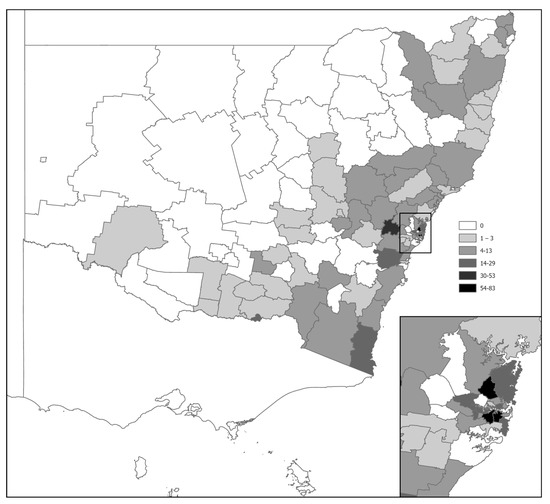

Meanwhile, 64.4% of the 132 local government areas in New South Wales have listed heritage conservation areas in their local environmental plans (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of heritage conservation areas listed in the local environmental plans of local government areas in New South Wales. The Australian Capital Territory has been left blank. Shading based on square-root transformed classes [63]. Data: State Heritage Inventory [64].

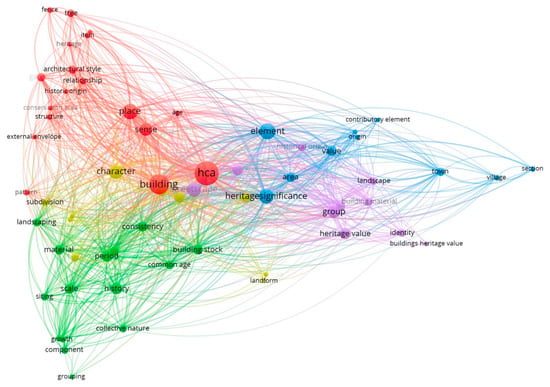

A content analysis of the key terms used in the council documents isolated 23 key phrases (Table 1). The most common terms used in the definitions are ‘heritage significance’ and ‘heritage values’, appearing in 57.6% of all formulations. This is followed by the constituent components, i.e., ‘buildings’, ‘streetscape’ and ‘elements’ (42.4%). A group of four descriptors, all appearing in 39.4% of all formulations, consider definable qualities such as ‘architectural style,’ ‘subdivision pattern’ as well as ‘group of buildings.’ In addition, the ‘character’ of a heritage conservation area is mentioned, without this concept being defined in the documents (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Frequency of key terms used in the definitions of heritage conservation areas.

Figure 3.

Network analysis of the various definitions of Heritage Conservation Areas used by local councils in NSW. Visualization of texts via VOS viewer.

‘Boiler plating,’ i.e., the use of standard formulations in planning documents and the uninhibited copying of formulations developed by another local government area for one’s own purposes, is a common feature of local government planning documents [65]. Indeed, identical or minimally modified formulations have been used by Ku-ring-gai Council [66] and Goulburn Mulwaree Council [67], the Hornsby Shire [68] and Bathurst Regional Council [69], as well as the Municipality of Hunters Hill [70] and Wingecarribee Shire [71]. Other councils extracted suitable sections from other councils’ work, such as the City of Newcastle [72] and the City of Willoughby [73] extracting sections from the Bathurst and Hornsby texts.

4.2. Classifying the Contributions of the Constituent Components

While council planning instruments may not define the raison d’être for heritage conservation areas, most development control plans, while referring to the definition contained in the local environmental plans often, but not always, contain provisions that define the nature of the constituent components of heritage conservation areas.

Several development control plans refer to ‘contributory buildings’ but do not define these. In total, 28 different definitions could be obtained from 24 local government areas. Two different formulations were encountered in documents created by four councils, mainly between formulations used in Heritage Studies and in Development Control Plans (Bayside [74,75], Blue Mountains [60,76] and Randwick City [77,78]), with additional variations between iterations of Development Control Plans (City of Sydney [2,79]). Slightly more than half the councils (54.2%) use a three-tiered system of ‘contributing,’ ‘neutral’ and ‘detracting’ building (Supplementary Data, Table S1). The latter class also goes under various other appellations, such as ‘non-contributory’ [80], ‘uncharacteristic’ [75], ‘intrusive’ [81] and ‘adverse’ [82]. While some councils, such as Mosman [82,83] and Newcastle [84], split the class of contributory components into two subclasses, almost a third of councils (29.2%) rely on the dichotomy ‘contributing’ vs. ‘detracting,’ omitting the neutral classification. The development control plans of four councils (16.7%) provide definitions for contributing items only (Hornsby [85], Ku-ring-gai [86], Marrickville [87] and Tweed [88]).

The length of the definitions defining contributing items varies widely (average 71.1 ± 44.9 words), ranging from the very brief, i.e., 16 words in the case of Bayside Council [74], to elaborate, i.e., 193 words in the case of Ku-ring-gai Council [86]. While the definitions of detracting items are generally shorter (average 36.8 ± 22.3 words,) with a range from 18 words (Blue Mountains [60]) to 83 words (Waverly [89]), there is no correlation in the verbosity of definitions of contributing and detracting items (r2 = 0.0656).

A content analysis of the definitions of items to be deemed contributory to heritage conservation areas isolated 74 different phrases which could be aggregated to 10 key phrases (Table 2), whereas the analysis of the definitions of detracting items identified 39 phrases which were aggregated to 6 phrases (Table 3). Among definitions of items to be deemed a contributor, the most prevalent phrases related to being ‘from a key period’ (used by 63.9% of councils) and that ‘contribute to the character of the area’ (59.1%) as well as definitions such as ‘possesses high degree of intactness/integrity’ and ‘contributes to the heritage/historic significance of the area’ (45.5% each). Being ‘consistent with the scale and form’ as an important element in the definition of items to be deemed contributory to heritage conservation areas was only mentioned by 9.1% of the councils, yet the reverse, i.e., being ‘inconsistent with the scale and form’ was noted as a criterion for items to be deemed detracting in 57.9% of council definitions (Table 3). While buildings that possessed a ‘high degree of intactness/integrity’ were deemed contributory by 45.5% of councils, buildings that were irreversibly altered were only deemed detracting by 15.8%. The definitions for items to be deemed neutral to heritage conservation areas seem to be primarily defined by being neither contributory nor detracting, with specific phrases such as “neither contributes nor detracts from the area’s character” (61.5%), “…significance” (23.1%) and “…streetscape” (23.1%) (Table 4). The nature of alterations also figures prominently, irrespective of whether they are reversible (38.5%) or irreversible (30.8%).

Table 2.

Frequency of key phrases used by NSW local councils in the definitions of items to be deemed contributory to heritage conservation areas.

Table 3.

Frequency of key phrases used by NSW local councils in the definitions of items to be deemed detracting to heritage conservation areas.

Table 4.

Frequency of key phrases used by NSW local councils in the definitions of items to be deemed neutral to heritage conservation areas.

5. Discussion

As the review of planning documents has shown, there is an absence of a clear definition of the functions and nature of heritage conservation areas. While the assessment of the cultural heritage significance of conservation areas can follow well established processes (i.e., in the Australian setting following the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter [56,58,90]), there is an absence of an agreed upon set of rules as to how the contributions of the constituent components within a given heritage conservation area can be classified. The following discussion will first consider the function of a heritage conservation area and then provide a working definition. This will be followed by a discussion on how to classify the contributions of the constituent components, again providing a working definition of the various classes. The discussion will conclude with a section on the conceptual parameters of managing heritage conservation areas, including an examination of curtilage.

5.1. The Functions of a Heritage Conservation Area

As noted, there is a lack of clarity when considering the role and functions of heritage conservation areas. Clearly, the appetite of state and local governments for the protection and conservation of heritage assets changes over time. It can be posited that this has been in a steady decline from its heyday in the late 1960s to 1970s, with iterations of relevant legislation being increasingly amenable to adaptive reuse and modification of heritage assets at the expense of the integrity of historic conservation areas and their heritage significance. In part, this reflects intergenerational change in community values [91] and aspirations. It also reflects an increasingly economic rationalist dominated political climate, although the role of heritage for the social and mental wellbeing of a community is being increasingly recognized in international conventions [92] and the academic literature [93].

In this context, it may be worth reaching back to the early objectives en vogue at the time heritage conservation areas were first conceptualized. In its preamble, the Minnesota (USA) Historic District Act of 1971 makes a forceful and eloquent statement that positions heritage conservation areas into the wider purpose of government:

“The spirit and direction of the state of Minnesota are founded upon and reflected in its historic past. In the effort to preserve the environmental values of the state, outstanding geographical areas possessing historical, architectural and aesthetic values are of paramount importance in the development of the state; in the face of ever increasing extensions of urban centers, highways, and residential, commercial and industrial developments, areas with an unusual concentration of distinctive historical and architectural values are threatened by destruction or impairment. It is in the public interest to provide a sense of community identity and preserve these historic districts which represent and reflect elements of the state’s cultural, social, economic, religious, political, architectural and aesthetic heritage”.[14]

Conservation areas can be more readily declared and managed in communities where development pressures are fewer and where, concomitantly, land prices are low. In areas where high-density and high-rise developments are common, the preservation of heritage conservation areas is controversial and caught between the tension of retention of the area for its heritage significance and associated societal benefits, the preservation of amenity values for NIMBY (not-in-my-backyard) proponents; and developers that desire to attain personal or corporate profits without any regard to the impact that it may have on the local and wider community [94,95]. Some of the motivations behind the declaration of heritage conservation areas, in particular in the USA, are primarily profit-driven, rather than guided by heritage conservation needs. For some, the development controls protected their assets in socio-economically desirable neighbourhoods [41], while for others heritage conservation areas conjure up the prospect of “prestige and tourist dollars” [15].

Amenity vs. Heritage Values

When circumscribing and defining heritage conservation areas as a general concept for the minds of the wider public, and when assessing the significance of a given heritage conservation area, caution needs to be exercised not to commingle cultural heritage values with amenity values. Amenity-based streetscape values are common in suburban areas where detached residences on landscaped blocks, often set in tree-lined streets, are the norm, providing residents with financial values, lifestyle opportunities and social comfort [96].

Unlike purely visual amenity-defined streetscapes, heritage conservation areas are underpinned by a statement of cultural heritage significance that identifies and spells out the cultural heritage values that describe and define the nature of a heritage conservation area (see below, Section 5.3). The risk of commingling is high, as much of public perception, as well as some of the literature, emphasise the economic benefits of heritage conservation areas to tourism. The Canadian Province of Quebec even expresses this as a specific aim when it defines a “historic district [as] a territory whose preservation benefits its residents, who live in an outstanding living environment, and the community, which benefits from economic vitality stemming from the heritage tourism” [97].

The risk of commingling cultural heritage values and amenity values was identified by the NSW Heritage Office in their ‘Guidelines for Managing Change in Heritage Conservation Areas’ where the authors noted that the public chooses to apply generic heritage arguments to protect neighbourhoods with uniform streetscapes and high amenity values from development. If approved, conservation areas based purely on amenity value would undermine the integrity of the heritage system and dilute the value of genuine heritage conservation areas. At the same time, public perceptions of amenity value as the driving force for heritage conservation areas could lead to significant industrial spaces, which by their nature have low aesthetic and amenity values, being overlooked or rejected as heritage conservation areas [45].

The approach taken in New Zealand is to employ a two-pronged approach, where heritage conservation areas are being supplemented by ‘Special Character Areas.’ These have notable or distinctive aesthetic, physical and visual qualities, including qualities that relate to the areas’ history and physical characteristics (specific era, architectural style, street and road patterns) [98]. While these special character areas are similar to heritage conservation areas, they are being managed for their amenity value and the aesthetic value of the streetscape rather than heritage values and thus have different regulatory controls applied to them. Given the emphasis on amenity values, while at the same time being less restrictive than heritage conservation areas with regard to permitted development, these special character areas are much sought after [99].

5.2. Defining Heritage Conservation Areas

Given the heterogenous nature of the local government areas, ranging from inner-metropolitan to rural councils, it is not surprising that the nature and make-up of heritage conservation areas varies widely across the state of New South Wales and across Australia in general [100].

Most heritage conservation areas in the urban core of communities are essentially streetscapes that have a common ‘character’ and belong to an identifiable period of urban development.

5.2.1. ‘Character’

As defined in the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment Act, a streetscape is “the character of the locality (whether it be a street or precinct) defined by the spatial arrangement and visual appearance of built and landscape features when viewed from the street” [47]. Yet, in various planning documents, the streetscape character is described by diffuse subjective terms such as ‘sympathetic,’ ‘compatible,’ ‘sense of place’ or ‘identity’ [101]. As noted by Tucker et al., “[w]ith a reliance on expert evaluation, the analysis of a streetscape is essentially an individual’s interpretation of what appears to be visually significant” [101].

The ‘character of the conservation area’ is a term commonly employed in both the published definitions of heritage conservation areas (Table 1) and the definitions of an area’s constituent components (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). ‘Character’ is not defined as a term in the various heritage acts, local development plans or in the development control plans, although the latter documents make liberal use of it. A 1998 publication by the NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning discusses the nature of the character of neighbourhoods, and how character analysis can be carried out, but it does not provide a definition. Rather, it maintains the previous levels of ambiguity [102].

In a planning circular dated to 2018, the NSW Department of Planning and Environment noted that “[c]haracter is what makes one neighbourhood distinctive from another. It is the way a place “looks and feels”. It is created by the way built and natural elements in both the public realm and private domain interrelate with one another, including the interplay between buildings, architectural style, subdivision patterns, activity, topography and vegetation” [103].

Character is circumscribed by definable and observable elements, such as architectural styles, building heights and set-backs, as well essentially intuitive, socio-cultural elements which manifest themselves in place-related phenomena such as ‘sense of place’ and ‘place attachment’ [93]. As van Wyk observed, in the planning sphere, “[c]haracter represents an aspirational confluence of local scale strategic visioning and statutory regulation. The concept lives in the collective imagination as the genius loci of place” [21].

None of the guidelines or literature on the topic of character comments on the fact that the identification and evaluation of character is a values-based assessment that is based on a culturally and socio-economically defined values set. Nor does the literature acknowledge that these values are mutable qualities on an intra- and certainly inter-generational level [91].

5.2.2. Definitions Used in Other Jurisdictions

In the Australian setting, the management of all non-moveable, non-Indigenous Australian heritage forms part of urban planning and land management and therefore remains the remit of the various state governments [104], while heritage conservation areas are used in other Australian jurisdictions such as South Australia (Historic [Conservation] Zones [40]) and Western Australia (‘Heritage Areas,’ and ‘Heritage Precincts’ [105]).

Western Australia regards a heritage area as “an area which has a distinctive character of heritage significance and which is desirable to conserve” and in its definition takes a streetscape-based approach by noting that, in heritage areas, “the relationship between the various built elements create[s] a special sense of place which is worth conserving. The significant elements may include the subdivision layout, the building materials or styles, or other streetscape elements such as fencing or garden layouts” [105]. Likewise, South Australia emphasises the “distinctive historical character or “sense of place” which is created by the combination of the buildings, the spaces between the buildings, the pattern of streets and allotments, plantings, street works and local topography” [40].

Internationally, the concept of heritage conservation areas is also used, under various appellations, in a large range of various countries (Table 5). Common to all is the specific concept of spatially circumscribed, thematic heritage conservation. Conceptually, many overseas jurisdictions focus on the architectural contribution of the included buildings (European Union [106]) as well as street patterns, such as Ireland [107] and France [9], while others place emphasis on the historic dimension (China [108]). Generally, the visual appearance of the heritage conservation areas is of great importance (Ireland [107], France [9]). The term ‘character’ and ‘heritage character’ is frequently used in overseas documents, but, like in Australia, is not defined (British Columbia [109], England [110,111], Ireland [107], China [108], Japan [108]).

Table 5.

Synonyms of heritage conservation areas in different jurisdictions (note that the legal protective controls and mechanisms may differ from those applied in NSW).

5.2.3. A Proposed Definition of a Heritage Conservation Area

Based on the foregoing discussion, this paper proposes the following consolidated descriptive definition of a Heritage Conservation Area. The aim of this text is to provide guidance for professional staff in local government authorities in conveying the purpose of heritage conservation areas to political decision makers, as well as the wider public in the general community.

“A Heritage Conservation Area is an area of land recognised and valued for the collective nature of buildings and elements in that area which distinguish it from other places and from its surroundings. The strong relationship between these buildings and elements creates a sense of place that the community values and that has cultural heritage significance which is deemed worth protecting.

A Heritage Conservation Area can include a group of buildings, streetscapes, landscapes or whole suburbs with particular heritage values, where individual places may not demonstrate significance on their own, but which collectively form a cohesive entity that give the Heritage Conservation Area a distinct identity.

The heritage values of a Heritage Conservation Area, and the cultural significance derived therefrom, can include historical origins, subdivision patterns, consistency of building materials or building styles, the common age of its building stock, planting elements, common uses and/or a layering of historical elements that provide evidence of the development of the area through various periods.

A Heritage Conservation Area aims to protect the heritage items and spaces that we value as a community whilst ensuring there is room for opportunity to adapt to changing needs. It is a way of managing change that allows development but ensures this is sympathetic with the local streetscape character and respects the conservation area’s cultural heritage significance.”

5.3. Classifying the Contributions of the Constituent Components

One of the guiding principles of the 1976 UNESCO Recommendations concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas provides a cogent framing on how to approach the conservation management of historic conservation areas. It noted that “[e]very historic area and its surroundings should be considered in their totality as a coherent whole whose balance and specific nature depend on the fusion of the parts of which it is composed and which include human activities as much as the buildings, the spatial organization and the surroundings. All valid elements, including human activities, however modest, thus have a significance in relation to the whole which must not be disregarded” [29]. It further posited that “[h]istoric areas and their surroundings should be actively protected, against damage of all kinds, particularly that resulting from unsuitable use, unnecessary additions and misguided or insensitive changes such as will impair their authenticity” [29].

The 1985 Granada Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe defined part of Europe’s architectural heritage as “homogeneous groups of urban or rural buildings conspicuous for their historical, archaeological, artistic, scientific, social or technical interest which are sufficiently coherent to form topographically definable units” which required signatory parties to “prevent the disfigurement, dilapidation or demolition of protected properties” through legislation and to “facilitate whenever possible in the town and country planning process the conservation and use of certain buildings … which are of interest from the point of view of their setting in the urban or rural environment and of the quality of life” [106].

In its 1987 Washington Charter on the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas, it defined the “[q]ualities to be preserved [to] include the historic character of the town or urban area and all those material and spiritual elements that express this character, especially urban patterns as defined by lots and streets; relationships between buildings and green and open spaces; the formal appearance, interior and exterior, of buildings as defined by scale, size, style, construction, materials, colour and decoration; the relationship between the town or urban area and its surrounding setting, both natural and man-made; and the various functions that the town or urban area has acquired over time” [42]. The Charter further posited that “[a]ny threat to these qualities would compromise the authenticity of the historic town or urban area” [42].

As noted earlier, neither the UNESCO Recommendations of 1967, nor the Granada Convention of 1985, nor the ICOMOS Washington Charter of 1987 found much traction in the Australian heritage management scene.

The investigation of cultural heritage values and the assessment of heritage significance follows well-established protocols. In the Australian setting, these are provided by the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter [58] with additional guidelines issued by the heritage authorities of the various states, such as NSW [56,122]) or Victoria [90]. It needs to be understood, however, that cultural heritage values are mutable qualities in general and specifically on intergenerational scales [91] and that therefore the attributed significance of a heritage conservation may change.

As heritage conservation areas are declared based on an evaluation of their cultural heritage values, which is a process essentially based on hindsight [123], it is inevitable that not all constituent elements in the area will belong to the period or focus of heritage significance. Some buildings will have been altered to suit the changed needs and demands of the occupants, while others may have been replaced by new builds that represent the architectural style and materials of that time, but that are incongruent with the style, form and scale of the existing heritage building stock that surround the new builds.

In submissions to the Productivity Commission’s enquiry into the Conservation of Australia’s Historic Heritage Places, some councils noted a lack of rigor when assessing heritage conservation areas and their constituent components. They observed that protection is often “a blanket style control in which all properties within the Heritage Conservation Area, regardless of heritage value, are affected by the controls and individual heritage buildings receive little recognition and are not supported by clear statements of significance” (Goulburn Mulwaree Council cited in [100]).

Early on, it had become clear that conservation areas, while a cohesive, spatially defined group of heritage assets connected by a common theme, might contain elements that were not congruent with that theme. Clearly, management strategies, such as demolition controls, would be different for items that were integral to the conservation area than for items that were incidental or even dissonant. Different levels of management controls will need to be brought to bear on the unaltered, original fabric and those that have already been modified (or replaced).

While the constituent elements of a heritage conservation area should be managed in a nuanced fashion, that may not always be the case. In their discussion, the authors of the ‘Guide on managing change in Conservation Areas’ noted that “[a] heritage area is identified by analysing its heritage significance and the special characteristics which make up that Significance. These may include its subdivision pattern, the consistency of building materials or the common age of its building stock. The least important characteristic is the ‘look‘ of the place, although the commonly held community view is that this is the determining factor” [45]. The 1982 National Trust guidelines for the assessment of Urban Conservation Areas proposed a traffic-light scheme that graded all contributory elements as ‘classified’ (i.e., heritage listed), ‘significant,’ ‘focal points,’ ‘unimportant’ and ‘visually disruptive’ [19]. Each of these comes with a set of suggested policy implications. For example, while the demolition or substantial alteration of ‘classified’ items should not be permitted, the demolition of ‘visually disruptive’ items should “where necessary…be encouraged” [19].

Integral to a heritage conservation area is that while its collective value is greater than the sum of its parts, each constituent element plays a role, either as contributing and enhancing the heritage conservation area, or as detracting from it.

One of the major cultural shifts in public sentiment, when it comes to home ownership, is the extent to which owners emphasise their “need” for privacy. At the time of their construction in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most suburban residential housing developments signalled an owner’s real or projected social status and ambition. Not only did the front façade of the house matter, presenting a public front, but this was augmented by the landscaped front yard. This front yard was a liminal sphere that mediated between the public space of the foot path and the private space encapsulated by the building envelope and the enclosed, out-of-sight backyard.

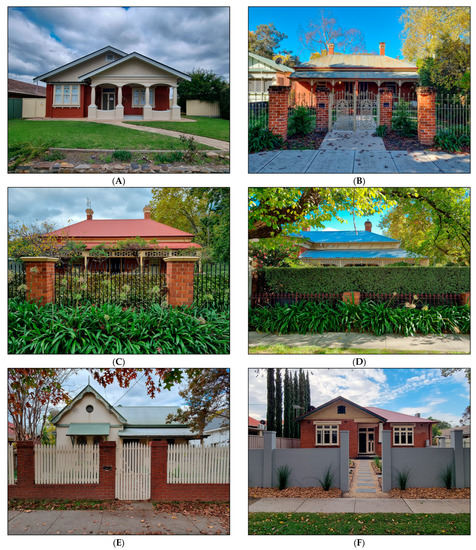

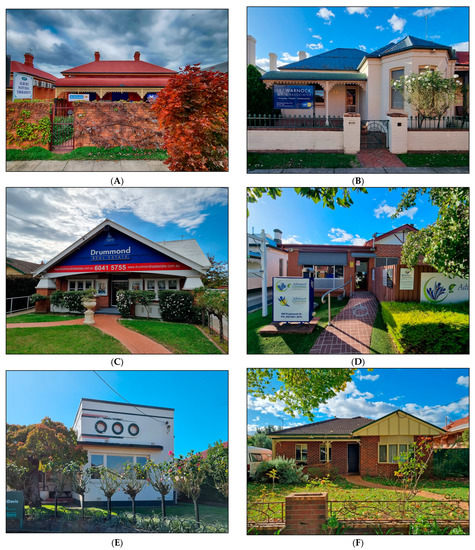

The role of the front yard has changed in the past two decades, morphing from the liminal to the private sphere, shielded from public view. This trend coincides with an increased level of individualism and decreased acknowledgement of communal and civic obligations. Consequently, property owners increasingly shield their properties from public view through the erection of closely spaced panelled fences, high walls, hedges or dense plantings (Figure 4 and Figure 5). While these do not affect the integrity of the building itself, they negate the building’s contribution and value to the public sphere of a heritage conservation area.

Figure 4.

Positive and negative contributions made by constituent components of heritage conservation areas facing the public domain. (A) Full visibility of the building from the street and footpath; (B) fence not in keeping with design period, but full visibility of the building from the street; (C) sympathetic fencing style, but fake plant panelling obscures the building; (D) manicured hedge obscures the building; (E) sympathetic fencing style, but height and closely set panelling obscure the building; (F) inappropriate fencing, in scale, materials (panels) and colour. All images: Bungambrawatha Creek Conservation Area, Albury, NSW, Australia.

Figure 5.

Positive and negative contributions made by constituent components of heritage conservation areas facing the public domain. (A) Brick wall obscures the building; (B) oversized signage obscuring part of the building; (C) inappropriate signage, both in scale and colour; (D) irreversible alterations (extension front left), unsympathetic window replacements, fencing and oversized signage; (E) historic infill with unsympathetic form but architecturally significant in its own right; (F) modern infill with sympathetic form, scale and materials. All images: Bungambrawatha Creek Conservation Area, Albury, NSW, Australia.

Adaptive uses of heritage properties in a heritage conservation area, commonly as professional premises and offices, necessitate signage that may not be commensurate with the building’s contribution and value to the public sphere of a heritage conservation area (Figure 6B) or that may not be sympathetic with the building itself. While the signage of the example shown in Figure 6C does not obscure the building and its form, it detracts due to its scale and extreme colouring.

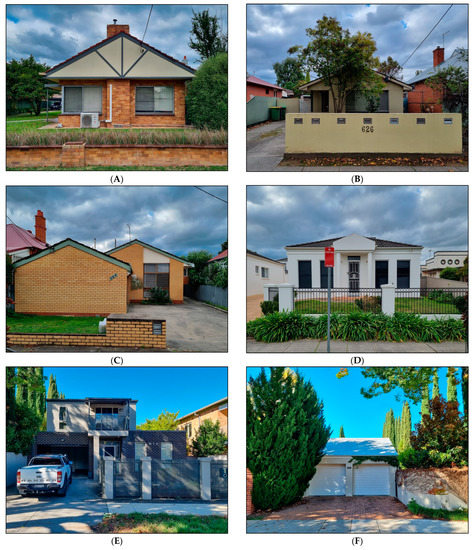

Figure 6.

Positive and negative contributions made by constituent components of heritage conservation areas facing the public domain. (A) Historic infill with sympathetic form but detracting materials (cream brick); (B) historic infill with sympathetic form but detracting materials (rendered) and dominant letter-box wall; (C) detracting infill both in form (garage up front, no windows) and material (cream brick); (D) modern infill with sympathetic form but detracting materials (rendered); (E) detracting infill in form, scale and material (rendered); (F) detracting infill both in form and function (garages). All images: Bungambrawatha Creek Conservation Area, Albury, NSW, Australia.

Common to all the foregoing examples is that these modifications do not affect the structure itself and that they can be rectified with a modicum of cost and effort. Other actions, such as additions (Figure 6D) or painting or rendering of originally exposed brickwork and/or changes to windows (e.g., replacement of original wood-framed double-hung windows with aluminium framed units), lead to a loss of integrity of the historic fabric. While some of these alterations can be partially reversed through restitution (e.g., windows), some cannot without damage to the fabric (e.g., painting or rendering).

5.3.1. A Proposed Set Criteria for the Evaluation of the Constituent Components

Based on the foregoing discussion, this paper proposes the following set of criteria for the evaluation of the constituent components that make up a heritage conservation area. The aim of this text is to provide guidance to local government authorities. The criteria are purposefully broad and as such allow for them to be narrowed, if so desired, to suit local community needs. All items in a heritage conservation area fall into three classes: contributory, neutral and detracting. The class of contributory has been split into three categories because the more granular grading allows for incentives and easily achievable improvements.

Contributory item, class 1: any building, work, tree or place and its setting which clearly reflects a key period of significance for the heritage conservation area and that forms a key element of the collective cultural heritage asset base of the heritage conservation area. This item retains its overall form as built during the key period of significance without additions or alterations visible from the street that are not congruent with the key period of significance. A key criterion is what the item offers to the streetscape or character of the heritage conservation area. As a result, the focus for a contributory item class 1 is how the item appears in the public domain, and especially from the street.

Contributory item, class 1b: an item that is structurally classified as a contributory item, class 1, but which is hidden or largely obscured from the public domain by detracting, but removeable additions (e.g., fences, walls, vegetation or advertising signage).

Contributory item, class 2: any building, work, tree or place and its setting which clearly reflects a key period of significance for the heritage conservation area. While this item retains its overall form as built during the key period of significance, it exhibits additions or alterations that are not congruent with the key period of significance and that are visible from the street, but that can be reversed (e.g., windows) or that are largely obscured by detracting permanent additions (e.g., carports).

Neutral item: any building, work or place and its setting that is either heavily altered to an extent where visual authenticity is compromised (e.g., a brick building that had been rendered), where the construction period is uncertain or which is from a construction period that falls outside any key period of significance for the heritage conservation area, but which reflects the predominant scale and form of buildings of the key period of significance for the heritage conservation area. The focus for neutral items is how the building appears in the street and public domain and that it does not detract from the streetscape character of the heritage conservation area.

Detracting item: any building, work or place and its setting which derives from a construction period which falls outside any key period of significance for the heritage conservation area and that has scale, form or building materials that is not consistent with the key characteristics of the area. The existence of detracting items in a heritage conservation area is not considered a basis for the introduction of development which is not cohesive with the identified significance of the heritage conservation area and does not set a precedent when assessing the merit of any new buildings within the specific conservation area.

It should be noted that once classified, the status of a property is not necessarily static. Assuming that owners are not malevolent and thus do not intentionally degrade their property, upwards improvements are possible in many instances. For example, the removal of an obscuring wall or fence, and its replacement with a more appropriate design, can readily elevate a class 1b item to a class 1 item. Some, but not all, modifications that make an original building a class 2 item can be reversed (e.g., removal of inappropriate windows or entrance doors) potentially elevating it to a class 1 status. Likewise, a detracting structure, such as a carport of unsympathetic design, can be demolished and replaced with a design that is sympathetic in scale, form and materials, thereby making it a contributory or neutral element in the streetscape.

5.4. Managing Heritage Conservation Areas

In 1972, Victorian heritage professionals, drawing on conservation planning experience in the gold-mining town of Maldon, influenced amendments of the Town and Country Planning Act and, with them, the insertion of strong protective provisions [30]. These stipulated that the “conservation and enhancement of the character of an area specified as being of special significance by prohibiting, restricting or regulating æ the pulling down, removal, alteration, decoration or defacement of any building, work, site or object in such area or by requiring buildings and works to harmonize in character or appearance with adjacent buildings or with the character of the area or (in the case of an area of historical interest) to conform to the former appearance of the area at some specified period and for such purposes specifying the materials colours and finishes to be used in the external walls of buildings or in the external coverings of such walls” [31].

These strong provisions became obsolete when the Town and Country Planning Act was repealed in 1987 and replaced with the Planning and Environment Act [124]. That act removed state-wide approaches but allowed local government areas to develop their own planning schemes.

Elsewhere in Australia, attempts at protection were much less ‘draconian’ [30]. The National Trust of NSW, in its 1982 discussion on Urban Conservation Areas, pointed out that “Urban Conservation Areas are not museum pieces. Many might be improved by the removal of disruptive elements, by appropriately designed new buildings, planting, and traffic rearrangement, as well as the authentic restoration of existing buildings. The important principle is to respect the essential character of the Area by preserving these elements which give the Area character, and to enhance that character by adding any new elements in a controlled, judicious and sympathetic manner” [19]. This, in essence, set the tone for the approaches taken by the NSW Heritage Office as well as local councils to the management of heritage conservation areas.

Given the devolved nature of heritage management, the nature and extent of controls that applied to heritage conservation areas were the remit of the local government area and stipulated in the development control plans. In 1996, the NSW Heritage Office released “Guidelines for Managing Change in Heritage Conservation Areas” which set out some suggested controls [45]. Since then, the heritage management process in NSW has become increasingly standardized, primarily by the State government mandating local governments to use standard instruments when formulating local environmental plans [54,55]. This has so far not extended to the formulation of development control plans.

This paper is not the place to discuss in detail the nature of actions that are deemed permissible, as these should be dependent on the specific needs of each heritage conservation area in maintaining their significance. In practice, they tend to vary, boiler-plating notwithstanding, between local councils in NSW, let alone between different Australian states or even globally [97].

An inherent risk in the establishment and management of conservation areas is that subsequent management actions aimed at reinforcing the cultural heritage significance may have unintended outcomes. Examples of historicization abound in the USA, where historic districts were retrofitted with ‘historic’ street furniture, and street and sidewalk paving were adjusted to reflect the relevant historic period [15]. Closer to home, the development of a set of historically correct standard set paint colours for Maldon resulted not only in an unexpected uniformity, but also found application in communities in other states with periods of different heritage significance, for which such paint research had not been undertaken [30].

Meanwhile, during the early period of heritage conservation areas, there was some disquiet by state government bureaucrats in Australian states that the concept could be used by residents as a mechanism to prevent unwanted development in their area irrespective of the heritage merit of the area [40]. This is echoed by similar concerns voiced overseas when considering historic districts [125]. Among the general public, this disquiet was founded on the general perception, as noted by Gow [37] and others, that heritage listing of properties infringes upon “the strong private property ethic in the colonial Australian psyche” [37]. The prevailing public perception, mainly among prospective buyers, seems to be that a heritage listing, be it as individual properties or via inclusion in conservation areas, might reduce retail values for properties [37], even though national and international economic studies [99,126,127,128] and community surveys [99,129] have shown otherwise. At the same time, many resident owner-occupiers, as opposed to non-resident investors, favour heritage conservation areas, primarily for their amenity values and the protection from unwanted development that they provide [41].

The rationale for the declaration of a heritage conservation area needs to be founded on sound and well-established principles of assessing its cultural heritage significance in terms of its historical, social, scientific or aesthetic value. Often, heritage conservation areas, initially declared in the late 1970s and early 1980s, have been carried through from one generation of planning documents to the next without ever questioning the intellectual basis on which they were nominated and initially listed [104].

A well-considered statement of significance is required if heritage conservation areas as a concept in general—and with their restrictions on alterations and adaptive use—are to be defensible in the face of mounting development pressures. At the same time, heritage conservation areas, as all heritage, fulfil a social function and thus need to remain fit for purpose, with hard-line approaches of “conservation for conservation’s sake” to be avoided.

Management Strategies and Development Controls

As noted earlier, the front façade of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century houses mattered, publicly signalling an owner’s real or projected social status and ambition. Effort was only expended, however, as far as the public view lines were concerned. This can be readily demonstrated when examining brick patterns and decorative cast iron work of the front and side façades (Figure 7). The set-back of the building formed a critical space, as it allowed the viewer, i.e., the public, to appreciate the property in its entirety. The front yard, with its appropriate plantings [130,131], created the critical liminal sphere that mediated between the public space of the footpath and the private space secluded behind the front façade. At the time of construction, these buildings not only projected an owner’s status towards the public sphere, but also referenced the other, pre-existing properties in the street, creating a streetscape of social ambitions.

Figure 7.

Differences in brickwork and decorative cast-iron work demonstrating historic view lines and owner’s representation. In addition to the veranda with cast-iron fretwork, the front façade exhibits bi-chromatic brickwork around the door and windows as well as brick courses laid in English Cross bond. The side of the building shows monochromatic brickwork around the window as well as colonial bond laid at a five-to-one ratio. Wyse Street Precinct, Bonegilla Conservation Area, Albury (NSW).

The architectural diversity of the properties reflects the tension between the original owner’s social ambitions and their economic realities. While sharing a common form and scale, subtle differences in materials readily demonstrate an owner’s economic limitations. The of use of bi-chromatic brickwork and ornamental cast-iron fretwork on verandas project affluence, while tighter construction budgets are reflected by the use of wooden fretwork or faux bi-chromatic brickwork (effected by painting the quoins).

It has been argued that liminal space between the footpath and the building provided for a two-way exchange. The owner of a dwelling has a right to view the public sphere from their property, both from within and outside the building, while the public has a right to look at properties from the public domain area of the footpath. Both share symbolic possession of the other space through coexistence and co-dependence [132].

Where the heritage significance of heritage conservation areas is defined by streetscapes representing a specific period of urban growth, the architectural diversity of the properties that had been erected within that key period of development reflects the social ambitions and their economic realities of the time. Their contribution to the streetscape, then as now, is therefore critical. It follows that the preservation and management of heritage conservation areas defined by streetscapes need to consider the significance of the liminal zone when balancing the personal demand for privacy against the public right to view and enjoy.

A person’s subconscious experience when walking through a streetscape is circumscribed by their field of vision. Given that, in heritage conservation areas, the contribution of individual properties to the public domain and streetscape is of importance, planning authorities have generally accepted that the contribution to the streetscape needs to be protected through regulatory preservation controls.

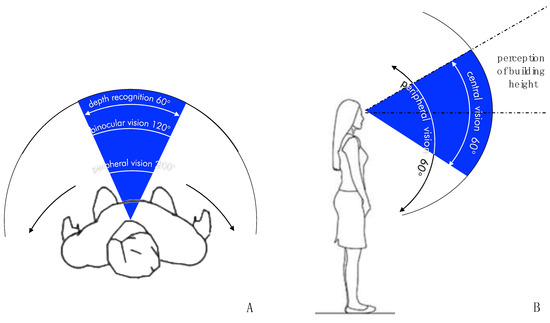

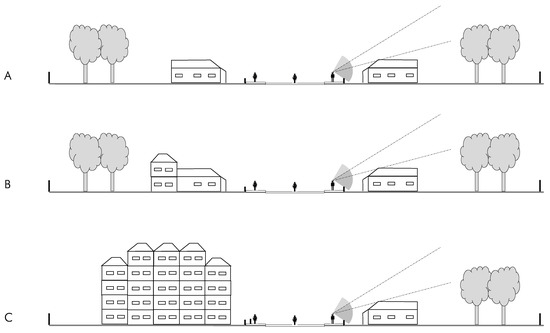

When considering approvals of aspects of alterations, infill and curtilage in heritage conservation areas, their impact on the public domain values, as defined by both horizontal binocular and vertical fields of vision, need to be considered. Given that the form and scale of the contributing items is of importance (see definitions), any alteration or addition to a constituent property, including the heightening of rooflines of additions to the rear of the property, should not be visible from the street, whereas elements of the properties that cannot be seen from the street should be exempt from preservation controls.

For the purposes of managing the public domain elements, some understanding of the human field of view is necessary. Setting aside minor variations among individuals, as well as formal vision impairment, the horizontal field of view among humans, without eye or head movement, is comprised of a 120° arc of binocular vision, with the central arc of 60° providing depth recognition. On both the left and right sides of the binocular vison are additional 40° arcs of peripheral, uniocular vision (Figure 8A). Human vertical vision is characterized by a 60° arc of central vision, with an additional 30° arc of upper and a 40–45° arc of lower peripheral, but out-of-focus vision (Figure 8B) [133]. For the perception of building height, the upper half of the vertical (in focus) vision (30° above horizontal) is of importance. The angle above horizontal for building height perception can be increased by an additional 30° with eye rotation [133]. Beyond that, head rotation is required.

Figure 8.

Key arcs of the human field of view. (A) Horizontal vision; (B) vertical vision.

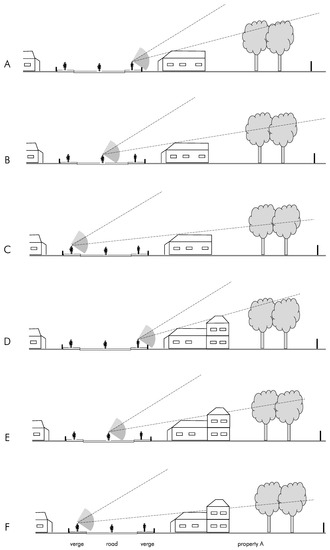

Given that heritage conservation areas represent heritage items in a spatial setting, the concept of isovists is particularly pertinent [134]. A façade isovist is the “planar area of urban space that a façade is visible from” [101]. Whether a modification is discernible within a person’s vertical field of vision depends not only on the placement and height of the alterations but also on the observing person’s position in a street, i.e., whether the observer is standing on the footpath in front of the property; in the middle of the street; or on the footpath on opposite site of the street (Figure 9). The distances of the observer in relation to the property determine the actual viewshed. This viewshed is not uniform but will vary between conservation areas, as it is influenced by several factors such as the overall width of the street including footpaths; the setback of the heritage item from the property boundary; the nature of the front façade and the shape of the roof (Figure 10).

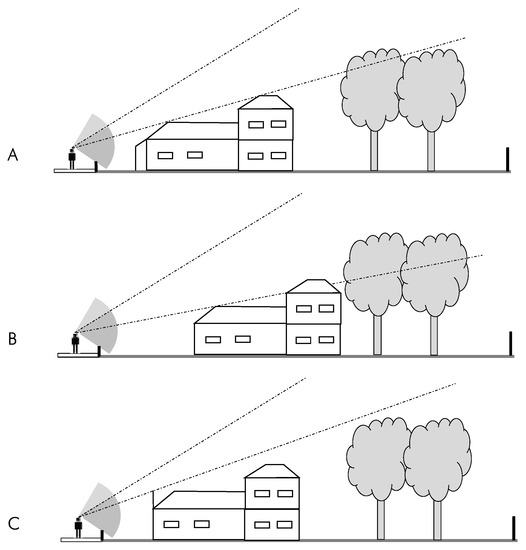

Figure 9.

Viewsheds of residential heritage properties in heritage conservation areas. (A–C) Viewsheds for unmodified buildings, as seen from the footpath (A), middle of the street (B) and footpath on opposite side of the road (C). (D–F) Viewsheds for buildings with double-storey extension at rear, as seen from the footpath (D), middle of the street (E) and footpath on opposite side of the road (F).

Figure 10.

Viewsheds of residential heritage properties in heritage conservation areas. Effects of setback and building shape. (A) Building with standard set-back; (B) building with increased set-back; (C) building with parapet on front façade.

5.5. Considering Curtilage

The need for proper curtilage was formally recognised in the ICOMOS Washington Charter of 1987, which noted that “[q]ualities to be preserved include the historic character of the town or urban area and all those material and spiritual elements that express this character…[including] the relationship between the town or urban area and its surrounding setting, both natural and man-made” [42].

Forming part of the planning framework of local councils, heritage conservation areas are spatially defined and bounded areas. For ease of convenience, the boundaries of heritage conservation areas coincide, in most cases, with property boundaries, even though some early concepts proposed placing the boundary in the centre line of the street, thereby also incorporating the street verge with the footpath [19]. While a heritage conservation area bounds those properties deemed to be significant, it is, conceptually, not a ‘hard’ boundary in urban settings. Rather, the heritage conservation area is embedded in the wider context of the urban space and at the time of identification and declaration blends into the background of other dwellings and structures that in most cases are contextually and proportionately similar.

Early on, concerns were expressed that such boundaries might “be misinterpreted as a magical division between valuable and worthless” [19] and thus would allow for unfettered development immediately outside the boundary. This is indeed the case, with any adjacent development only limited by the terms of the general local planning controls that are applicable to that zone (i.e., residential, mixed residential/commercial, etc.). If left uncontrolled, however, that may generate an island effect where the heritage conservation area is surrounded by a sea of modern, high-density developments with heights that far exceed the building’s heights prevalent in the conservation area. In its 1996 guidelines, the NSW Heritage Office discussed the concept of buffer or transition zones between a heritage conservation area and the urban core [45], but it seems that these were never implemented in NSW.

As noted earlier, a person’s subconscious experience when walking through a streetscape is circumscribed by their field of vision, with the skyline playing a major role in visual amenity assessments [135,136,137]. Given that heritage conservation areas represent heritage items in a spatial setting, the concept of isovists can also be applied when examining features that intrude on the skyline and visual character of a streetscape. The assessment and statement of the cultural heritage significance of a specific heritage conservation area and its setting will define to what extent considerations of skyline and height or additions and surrounding new developments will have to be considered in decision-making processes (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

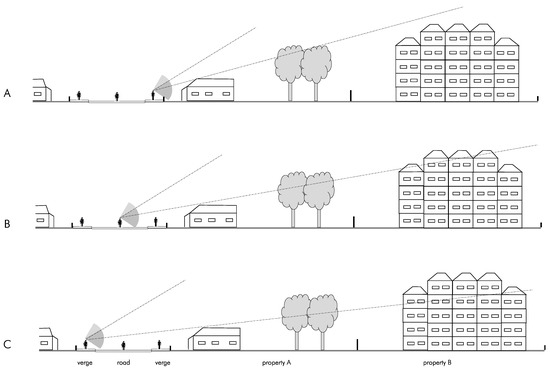

Figure 11.

Curtilage and viewsheds of residential heritage properties in heritage conservation areas. Effects of multi-storey construction on properties behind and outside a heritage conservation area. (A) Viewer’s position on same side of the street as the heritage asset; (B) viewer in the middle of the road; (C) viewer on opposite side of the road.

Figure 12.

Curtilage and viewsheds of residential heritage properties in heritage conservation areas. Effects of construction on the side of the street opposite to a heritage conservation area. (A–C) different building heights and designs.

This then raises the question of curtilage. Curtilage is commonly considered to be the area of ground that is directly connected with the functioning or inhabitation of a structure. In numerous development control plans, the curtilage of heritage places is often referred to as the setting [138] or as “areas that are integral to retaining and interpreting the heritage significance of places” [139] The Standard Instrument for Local Environmental Plans defines that “curtilage, in relation to a heritage item or conservation area, means the area of land (including land covered by water) surrounding a heritage item, a heritage conservation area, or building, work or place within a heritage conservation area, that contributes to its heritage significance” [55]. This formulation also found its way into the development control plans of several metropolitan [2,77,85,140,141,142], regional [88,143] and rural local government authorities in NSW [138].

The Model Heritage Provisions for Local Environmental Plans issued by NSW Heritage include the provision, with respect to development of heritage items that “[t]he consent authority may refuse to grant any such consent unless it has considered a heritage impact statement that will help it assess the impact of the proposed development on the heritage significance, visual curtilage and setting of the heritage item”[52].

The NSW Heritage Office identifies four types of terrestrial heritage curtilage: “(i) lot boundary curtilage, which reaches to the edge of the property lot; (ii) reduced heritage curtilage, which is less than the lot boundary; (iii)·expanded heritage curtilage, which exceeds the lot boundary and protects the setting or visual catchment; and (iv)·composite heritage curtilage, which applies to heritage conservation areas and defines the boundaries of land required to identify and maintain the heritage significance of a historic precinct, village or district” [144].

Of critical consideration in the case of heritage conservation areas is the concept of expanded heritage curtilage.

“In defining an expanded heritage curtilage the prominent observation points from which the item can be viewed, interpreted and appreciated must be identified” [145].

Ideally, any proposed alteration and development in a heritage conservation area should include a viewshed modelling and analysis from various observer positions. Care needs to be taken that the modelling reflects the 120° arc of binocular horizontal vision and the 30° arc of building height recognition. Photomontage simulations, which are common approaches, are inadequate, as noted by Tara et al., in their discussion of visual amenity conflicts in Brisbane (Queensland, Australia) [146]. The inherent problems are the field-of-view limitations of lenses used on high-quality, full-frame (i.e., 35mm-equivalent) digital cameras: standard 50 mm lenses have 40° horizontal and 27° vertical angles of view, while 24 mm wide-angle lenses have 74° horizontal and 53° vertical angles of view [147]. The use of 12 mm lenses, with a 111° horizontal angle of view, approaches the full width of human binocular vision, but results in considerable distortion at the lateral margins. True, single point-of-view, undistorted 120° photography can be achieved with 35 mm and medium-format film cameras [148,149].

6. Conclusions

As this review has shown, heritage conservation areas are widely used in heritage protection as exercised through local government planning instruments in New South Wales and elsewhere in Australia. Yet, there is no formal definition provided by the State heritage office as to what constitutes such an area and what function it fulfils. Consequently, it was left to the local government authorities to create their own definitions to describe the concept of a heritage conservation area, as well as to provide definitions for the classification of the contributions made by a given area’s constituent components. Not surprisingly, the definitions diverge widely, both in overall scope and level of detail.

Based on a systematic review of local government documents, this paper has provided a consolidated definition that describes both the conceptual nature of a heritage conservation area and the function it fulfils in the protection of a community’s cultural heritage (Section 5.2.3). To paraphrase a section of the previously cited Minnesota Historic Preservation Act [14], the spirit, identity and direction of a community is founded upon and reflected in its historic past, and heritage conservation areas represent and reflect a spatially circumscribed group of elements of the community’s cultural, social, economic, religious, political, architectural and aesthetic heritage which is deemed worth protecting.