1. Introduction

In the historiography of Novohispanic art, there are plenty of references to both folding screens [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], and lacquer, mainly those made in the present-day states of Michoacán and Guerrero [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Folding screens, as well as lacquer itself, were originally Asian phenomena, which were later adopted and further developed in New Spain. Folding screens are usually made of between 2 and 24 leaves and are used to divide rooms or to be displayed against a wall. Their size, material, technique, and iconography are very diverse. Until the 16th century, all the production centers were in Asia, but the taste for folding screens expanded along with the European expansion to Asia and the Americas. As a result, in the 17th century, Spanish America became a production center itself.

Lacquer originated in East Asia, where the resin from the lacquer tree

Toxicodendron vernicifluum was used to protect objects and, at the same time, created effects of brightness, translucency, luminosity, and depth. Asian lacquer was renowned in Spanish America from the late 16th century, thanks to the trade of the Manila Galleon. Even before this, however, Spanish

conquistadores discovered animal-based (in present-day Mexico) and plant-based (in South America) procedures that, over time, came to be considered lacquer since their effect was like that of Asian lacquer [

10,

11]. From the 17th century, Asian lacquer also inspired the development of European lacquer techniques, which differed from Asian ones [

12]. European lacquer procedures were known in New Spain in the 18th century [

13,

14,

15].

Therefore, in Spanish America, different kinds of lacquer coexisted. They were called

maque, after Japanese

makie lacquer [

15] (p. 145). The word

maque has often been believed to refer solely to regional techniques that had pre-Columbian origins [

15] (p. 145, note 60). Nonetheless, documentary analysis demonstrates that the word

maque was used very liberally. Far from simply relating to a particular technique, it was used to refer to different Asian, European, and Novohispanic works that shared a similar lustrous effect.

In Novohispanic documents from the 18th century, references to lacquer folding screens include the terms lacquer (

maque,

maqueado,

amaqueado,

amacado), lacquer-like (

con pintura maqueada), and imitation lacquer (

al remedo de maque,

fingido de maque). All these terms are used interchangeably; techniques and procedures are not clearly distinguished from each other, yet all in all, they attest to the big success of lacquer folding screens in New Spain in the 1700s. At this stage of research, when technical studies are yet to be done, it is not possible to offer a clear definition of each production. However, close attention will be paid to the specific terms used in each case, and they will be thoroughly translated throughout the paper. Additionally, the Spanish version of this essay, including all the original documentary references, is available as a

Supplementary File.

In New Spain between the early 17th century and the late 18th century, the techniques, iconographies, materials, and uses of folding screens multiplied. In the same period, in Uruapan, Peribán, Quiroga, and Pátzcuaro (in the present-day state of Michoacán), Olinalá (Guerrero), and Chiapa de Corzo (Chiapas), objects were made with lacquer techniques of pre-Columbian origin, based on chia or linseed oil and the fat extracted from the female axe insect (Llaveia axin axin). These techniques were totally unrelated to the Asian and European ones; while pre-Columbian techniques are very important, more lacquer folding screens and other large furniture pieces exist, made with different techniques, including the lacquer and painting techniques of European origin. These works should be studied jointly to better understand the true scope of the taste for lacquer in New Spain.

Japanese lacquer was the first kind of Asian lacquer that widely circulated in Europe and Spanish America. But from the second half of the 17th century on, Chinese lacquer folding screens were better known in both areas. In New Spain, folding screens and lacquers developed independently of each other, but in the 18th century, the popularity of Chinese lacquer folding screens encouraged the manufacture of Novohispanic lacquer and imitation lacquer folding screens. Prior to this, there is no evidence that these forms were made in New Spain, hence the affirmation that they were inspired by Chinese lacquer folding screens.

The study of Novohispanic lacquer and imitation lacquer folding screens has been relatively neglected, even though some works and a few dozen documentary references are known to exist. In large cities, customers would commission folding screens from painters and coach makers; they would also sometimes order them from lacquer workshops in Michoacán and Guerrero. Therefore, by the mid-1700s, besides Chinese and European lacquer folding screens, there were different kinds of Novohispanic ones in New Spain (

Figure 1). Since many works were made to order, there was a great variety: lacquer folding screens could be intended for the

estrado (a raised platform), the bedrooms, or other places in the house. The number of leaves would vary between 6 and 24, and screens could be decorated on one or both sides. Some lacquer folding screens were luxury items—the imported ones could cost up to 625 pesos, but some others would be as little as 10 pesos.

As technical studies of Asian, European, and Spanish American lacquer advance, it becomes more easily noticeable that all of them greatly vary in their materials and procedures. The aim of this paper is not to describe all the lacquer procedures used in Novohispanic folding screens but to demonstrate that lacquer folding screens were highly popular in New Spain, which led to a still little-known technique of diversification we are yet to explore. It also aims to prove that, while Chinese lacquer screens were undoubtedly the source of inspiration for Novohispanic lacquer folding screens, they did not mean to copy them but selected some of their features, like color and certain figures, to recontextualize them in works that were generally much closer to other Novohispanic paintings than they were to Chinese art.

The phenomena of lacquer folding screens in New Spain include those works made in regional lacquer centers but go far beyond them. Many scholars of Novohispanic art had thought that Novohispanic lacquer folding screens were only made in Pátzcuaro. In 2022, Ronda Kasl rediscovered

Tardes americanas (1778), which mentions a lacquer

rodastrados (a screen for a dais) among other lacquer works made in Michoacán for the Marchioness of Cruillas, wife of the Viceroy of New Spain (1760–1766) [

16,

17]. A well-known quote from Francisco Ajofrín (1763) mentions that the artist José Manuel de la Cerda, based in Pátzcuaro, was making one dozen lacquer trays for the vicereine [

18]. Granados y Gálvez does not explicitly refer to Pátzcuaro or De la Cerda, but the

rodastrado and the other lacquer pieces owned by the Marchioness of Cruillas would likely have been made by De la Cerda, who was the most prestigious lacquer artist of his time.

However, New Spain was not the only place making lacquer folding screens. Lacquer folding screens were made in Spain from the late 17th century, and this paper will discuss evidence that suggests that some Novohispanic lacquer folding screens are related to those made in Europe.

The diversity of techniques and production centers has yet to be considered in the historiography, and to assess their true importance, lacquer folding screens should be studied together since this is the only way to understand their success in New Spain. While Chinese lacquer screens circulated widely in Europe, it was in New Spain where their popularity inspired the production of different types of folding screens that, while inspired by the Chinese originals, went far beyond merely copying them. Between them, Novohispanic lacquer and imitation lacquer folding screens demonstrate that the Spanish American market for Asian art was considerable, and the appetite of Spanish America for lacquer was a significant and little-known aspect of the globalization of art in the 18th century.

In Europe, lacquer from the 16th–18th centuries is usually seen as a phenomenon that only involves Asia and Europe. In the Americas, on the other hand, it is seen as a phenomenon solely relating to Asian and Spanish American (pre-Columbian-type techniques) lacquer. Direct trade between the Philippines and New Spain led to the development of unique phenomena, like Novohispanic lacquer screens, whose variety demonstrates to what extent Novohispanic lacquer contributed new dimensions to the already rich world of lacquer in this period. The study of Novohispanic lacquer allows us to better understand the early globalization of art and lacquer.

3. Results

3.1. Lacquer and Screens in Spanish America: An Outline

Folding screens and lacquer were known in New Spain at the end of the 16th century, thanks to trade with Manila. Both were highly popular from the beginning. The first folding screens and lacquer objects known in the Americas were Japanese [

19]; both inspired different kinds of Novohispanic works [

20,

21]. Japanese screens of this period were usually made of painted paper. In New Spain, folding screens included

rodastrados, decorated only on one side and displayed against the walls of a dais used by women. As they were used on a raised wooden platform,

rodastrados were low (between 83.6 and 139 cm high).

Biombos de cama, designed to shield beds at night, were between 205 and 250 cm high. Also popular were double-sided folding screens, which were decorated front and back. Many folding screens were painted and depicted different topics; others were made of brocade and other fabrics. Many of these screens were totally unrelated to Asian examples, aside from being the same kind of furniture form.

The best-known lacquer folding screens are Chinese Coromandel pieces, which in Europe were often disassembled so that their panels could be used to decorate other furniture or displayed on walls (

Figure 2). Spain was an exception since not only were screens disassembled less often than they were in other European areas, but there were also different kinds of Spanish and Spanish American folding screens, including lacquer ones. Therefore, the taste for folding screens was not only widespread in New Spain but also in Spain, where, in the 17th and 18th centuries, more folding screens, lacquer or not, were produced than in any other European nation [

22].

In New Spain, Chinese lacquer screens might cost between 50 and 500 pesos (see

Table 1 and

Table 2), while the price range of those made of Novohispanic lacquer and imitation lacquer might be 8–80 pesos but would seldom be more than 25 pesos (see

Table 3 and

Table 4). While Chinese screens were much more expensive than Novohispanic ones, there also were significant differences between the Chinese screens themselves. This is true even for works that are described similarly, which suggests that the appraisals—and the customers—were very aware of the features of individual works. Sometimes Asian objects would be appraised by dealers who were able to distinguish the quality of the works since they were based at Parián, a market specializing in Asian items. For their part, Novohispanic folding screens would be appraised by painters, which suggests that it was painters who would be primarily involved in their manufacture.

3.2. Asian Lacquer Screens for the Spanish American Market

There were Asian productions meant for specific European markets, such as the British and the Dutch [

23,

24,

25]. Other works were adapted for the Spanish American market, but they are poorly known outside of the Spanish-speaking world. Foremost among them are lacquer screens. In 1769, the cargo of the galleon Nuestra Señora del Carmen from Manila to Acapulco contained, among other materials, “one box with 52 leaves of red lacquer for two folding screens” [

4] (pp. 37–38). The following year a “folding screen of red lacquer with golden flowers, two sided, with 24 leaves” [

26] was shipped from Manila to Acapulco.

Folding screens that had more than 20 leaves are relatively common in Novohispanic inventories, but they are very scarce in other areas. The “folding screen of red lacquer with golden flowers, two sided, with 24 leaves” was surely intended to divide a large room. Most screens that had more than 20 leaves were

rodastrados, but that is not the case here since the work was decorated on both sides. This allows us to suppose that the screen was made to order. Little is known about Asian works commissioned by Novohispanic customers. Baena Zapatero has posited that this screen was made in Manila [

4] (pp. 37–38). This is indeed a reasonable possibility since Manila was not only a distribution center of Asian works but also a production center. Nonetheless, we do not know to what extent the residents of Manila—either Chinese or Philippine—would get directly involved in the production of goods for the Novohispanic market. But since this was a very important market and many people in Manila made a living from trade, it is reasonable to assume that some Asian works shipped to New Spain—especially those that were inexpensive—would have been made in Manila. Whether lacquer screens were among the works made in Manila is an issue to be discussed in the future and will need more evidence.

Chinese red lacquer screens were uncommon outside of Spanish America, but they were highly popular in New Spain in the 18th century. As can be seen in

Table 1, they often were luxury items:

Table 1.

Red Chinese lacquer screens.

Table 1.

Red Chinese lacquer screens.

| Chinese Lacquer Screen Description |

|---|

| “One red lacquer rodastrado also from China with 12 panels” and “one red lacquer screen from China with 10 panels.” [27] |

| “One folding screen from China, of red and gold lacquer, with 12 panels and golden crests for 300 pesos” and “one new folding screen, from China, of red and gold lacquer, two varas and three cuartas high, with twelve panels and its golden crest for 500 pesos.” [2] (p. 29) |

| “One rodastrado … with twenty-four panels, of red and golden lacquer, and crest of the same [material] for 500 pesos”, “Yt one screen from China, of red and gold lacquer, and golden crest, for 300 pesos” and “One new folding screen from China, of red and gold lacquer, two varas and three cuartas high with twelve panels and golden crest for 400 pesos.” [28] |

These Chinese red lacquer folding screens were undoubtedly destined for the Novohispanic luxury market. Price ranges of between 300 and 500 pesos would correspond to works made to order. Both the Marchioness of Altamira and the Marquis of Guardiola were wealthy and socially significant individuals [

29]. Direct trade with Manila facilitated the spread of Asian works, which circulated widely during much of the colonial period. Hence the evolution of Novohispanic tastes gave a place to goods not found in other areas.

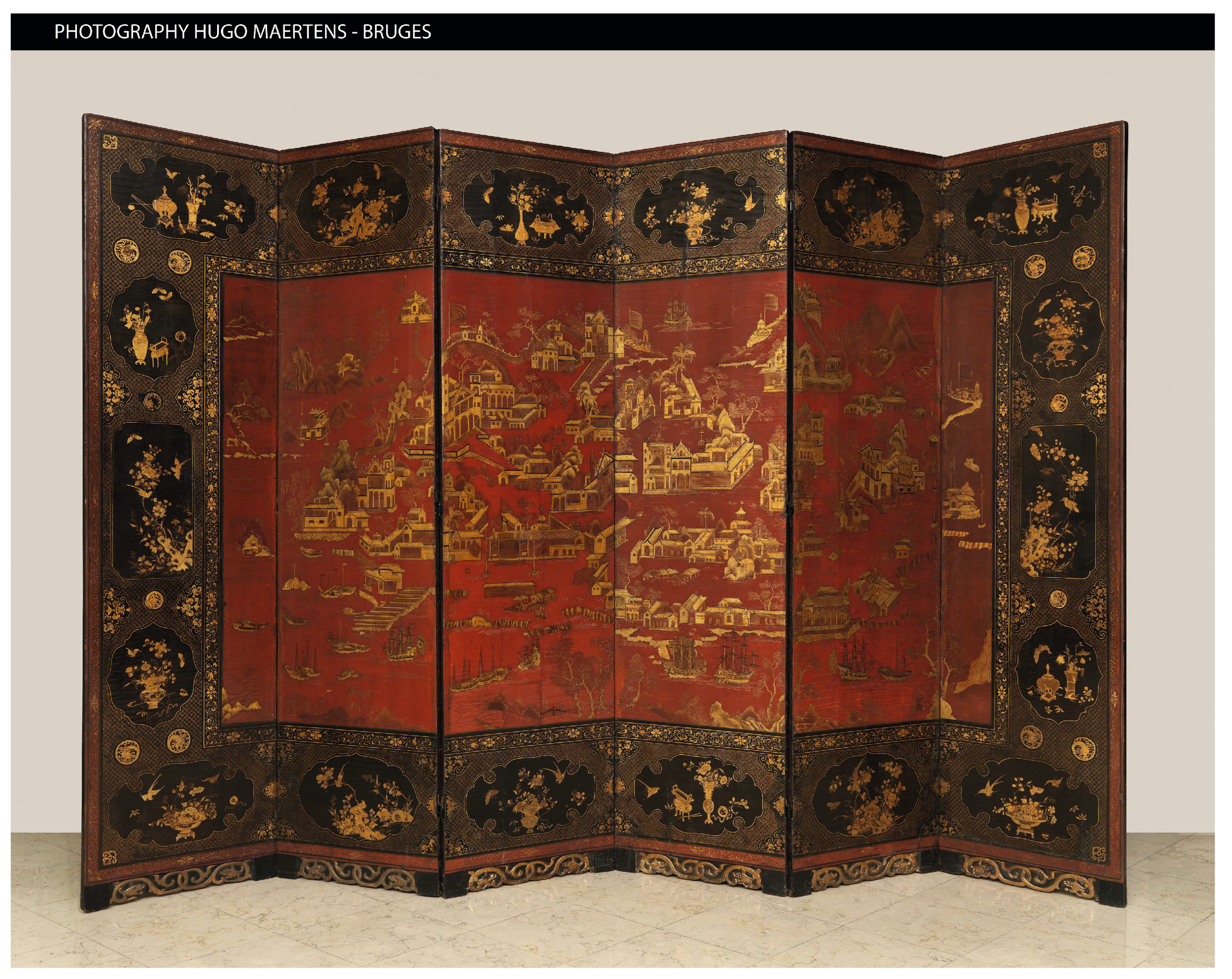

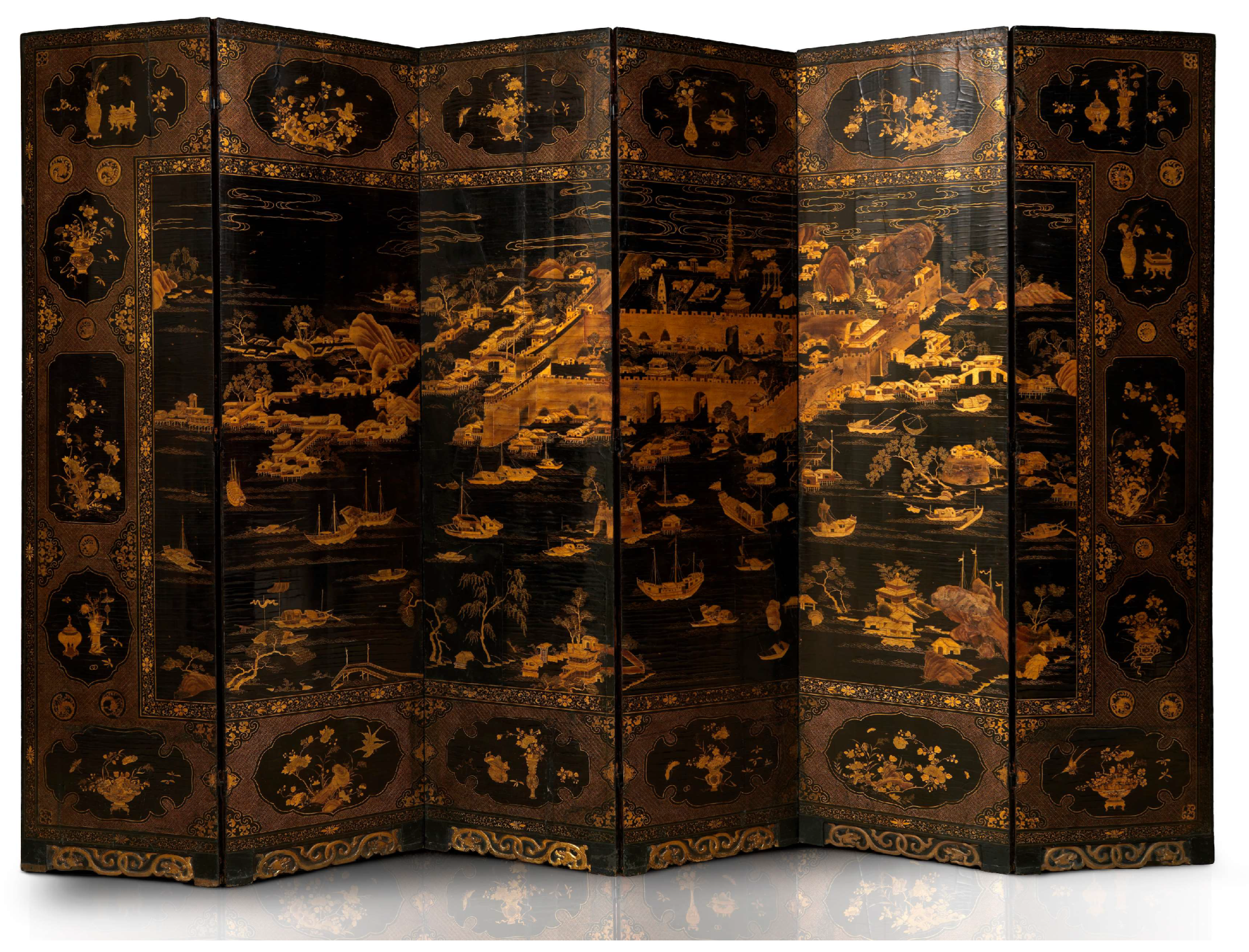

Double-sided Chinese lacquer folding screens which combine black and red backgrounds are also of interest. In 1737 Joseph del Barrio, Knight of Santiago, had “one folding screen with boards, twelve leaves, from China, of red and golden lacquer on one side and black on the other, in 250 pesos” and “One lacquer folding screen from China, two-sided, crimson and black, appraised for 90 pesos” [

30]. While these kinds of folding screens were uncommon, the Museu do Oriente in Lisbon exhibits a Chinese lacquer folding screen whose front is red, surrounded by a black frame, whereas the backs of the screens are black (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The work depicts a view of Macao on the front and a view of Canton on the back. The latter was an

entrepôt between East and West, but Macao was particularly important for the Iberian market, which suggests that this folding screen—similarly to those owned by José del Barrio—might have been made for that market.

Equally evocative is an Indo-Portuguese lacquer folding screen whose background combines red and black; Portuguese figures are depicted on it, and the top of the work shows poly-lobed crests [

31]. Many 18th-century Novohispanic folding screens have similar crests. These are never found in folding screens from the 17th century, which allows us to assume that the former adopted crests from contemporary Asian screens. Different items traded by the Portuguese arrived in Manila, so the folding screens described in Barrio’s inventory might well have been like these Chinese and Indo-Portuguese works.

Chinese black lacquer folding screens also circulated in New Spain. One ex-voto (votive offering) for the Virgin of Tlatocán, by José de Páez (1751), depicts a black lacquer

biombo de cama [

32] which seems to be Chinese, not Novohispanic Chinese style. Also, in 1729, the Marchioness of Altamira had “another said [

rodastrado from China] of black lacquer with 22 panels” [

27], and in 1751 the Marquis of Guardiola had “Yt another folding screen from China black and gold, 2

varas and three

cuartas high, with 12 panels, in 200 pesos” [

28]. These references are less numerous than those to red Chinese lacquer screens. The latter might have been more popular, but as we can see in

Table 2, many references to Chinese lacquer screens do not mention color, and some of them were undoubtedly black.

Table 2.

Chinese lacquer screens.

Table 2.

Chinese lacquer screens.

| Chinese Lacquer Screen Description |

|---|

| “One lacquer arrimador [rodastrado] from China, with 23 panels, one and a half vara high, appraised for 115 pesos.” [33] |

| “Ytem one lacquer folding screen from China, with 12 panels, three varas high appraised for 150 pesos […]”“Ytem one lacquer rodastrado from China, 23 panels, one vara and a half high, appraised for 150 pesos.” [34] |

| “One folding screen. Of lacquer, from China, with 6 panels, for 50 pesos.” [35] |

| “Two folding screens, one small, lacquered, from China…” [30] |

| “One lacquer folding screen from China, two-sided, for 200 pesos.”“Another said, also lacquer from China, bigger, for 240 pesos.” [2] (p. 32) |

| “208. One lacquer folding screen from China, two-sided, for 200 pesos.”“Another said, also lacquer from China, bigger, for 240 pesos.” [36] |

In the same way as the folding screens previously discussed, these are also very diverse in terms of use, number of leaves, size, and price. A good example of this is “One lacquer arrimador [

rodastrado] from China, with 23 panels, one and a half

vara high” which in 1695 belonged to the Marchioness of San Jorge and was inherited by her uncle, Bentura de Paz. In 1695 the screen had been appraised at 115 pesos; in 1704, it was appraised at 150 pesos. This is exceptional since the 1704 document shows that many of the other objects from the 1695 inventory had depreciated [

37]. Over time, if objects remained in good condition, their prices would likely remain the same but certainly not appreciate in value. Two screens that were in the inventory of the Count of Xala in 1784 and in his widow’s inventory of 1792, for example, had the same value in both instances. In other entries, none of the listed references mention the incised relief work that characterizes Coromandel screens, which suggests that they did not circulate widely in New Spain. Since the wealthiest Novohispanics paid as much as 500 pesos for Chinese lacquer screens, the scarce circulation of Coromandel screens would likely be because the Novohispanics preferred works tailored to their tastes, for example,

rodastrados, two-sided screens, and those with red backgrounds.

3.3. European Lacquer Screens

European lacquer screens have received little attention, despite the evidence for their existence in Italy [

38], France [

38] (p. 78), England [

15] (pp. 170 & 172), and Germany [

39]. These screens were made with European lacquer techniques. In Spain, lacquer screens, both Asian and European, were relatively popular, namely in the court of Isabella Farnese [

40,

41]. But the liking for them predates this: the inventory of the Knight of the Order of Santiago and former member of the Council of the Indies, Jerónimo de Eguía (1682), mentions “one folding screen from Madrid of eight panels, each one

vara wide and two

varas and one cuarta high, the front gold and painted with different colors and the back varnished with black paintings” [

38] (p. 163). This document mentions another ‘varnished folding screen’ (

“un biombo …

embarnecido”), but it specifies that it was from India” [

38] (p. 163). Both works are lost, but the reference to Madrid lets us suppose that such a screen was decorated in the capital of Spain using local lacquer techniques [

42].

Years later, Isabella Farnese had lacquer screens made in Italy and Spain. The Queen’s fondness for lacquer and

chinoiserie is well known [

40], so her taste for European lacquer screens comes as no surprise. The inventory, made upon her death in 1746, records “One lacquer screen with eight leaves, the background in the color of pearl shaded with different figures, and flowers cut in paper, two-sided, every leaf is one foot and nine fingers wide, six and six height” [

38] (p. 391); in this case, as Ordóñez Goded has noted, the reference to cut paper corresponds to Italian

lacca povera [

38] (p. 391). The same document records “another new screen made in the Real Sitio de San Ildefonso, black background, shaded with golden bunches, flowers of different colors, and birds, everything in relief, with crest of the same [work], and a small basket of fruit in the middle” [

38] (p. 392). There is also evidence that, in 1736, the Queen commissioned a European lacquer screen [

42] (p. 79).

But Isabella Farnese was not the only one who liked these works. When her successor, Barbara of Portugal, died in 1758, she had “one folding screen of six leaves which is on one side of the color of olive and on the back of the color of lemon, which has golden bunches and is made of lacquer garnished with wood carved in white” [

38] (p. 392). It is interesting that European lacquer used the colors pearl, olive, and lemon, unlike Asian ones, whose palette was very restricted [

42] (p. 81). European lacquer, like Novohispanic lacquer, did not solely imitate Asian examples but developed solutions of its own.

In New Spain, there are a few explicit references to European lacquer, but of great interest is this record from the inventory of the Marquis of Guardiola (1751): “Yt one English red lacquer

rodastrados in 500 pesos” [

28]. This rich inventory contained 11 screens, including five Chinese lacquer and five Novohispanic ones. Therefore, the exceptional reference to an English screen must be accurate. Since it is a

rodastrado, it must have been made expressly. By 1730, the prestigious English cabinet maker Giles Grendey, widely known for his japanned work, had made an important set of red lacquer furniture, probably for a Spanish client. The set is currently at the Lazcano Palace [

43]. While little is known about the works that the wealthiest Novohispanics commissioned in Europe, their ostentatious taste for luxury screens is well known. While japanned screens are not common, one example survives, two-sided with six leaves, one of which is red and the other dark green [

15] (p. 172).

A few European lacquer pieces are mentioned in Novohispanic inventories. References are found in wealthy inventories where works are appraised for very high prices. In fact, the most expensive lacquer object recorded in New Spain is “One clock by Elicot [sic for Ellicott], with music and a white lacquer box” [

44] appraised for one thousand pesos in the inventory of the Count of Xala, in 1784. Therefore, the Marquis of Guardiola’s English lacquer

rodastrados suggest that in the 18th century, screens were occasionally among the luxury lacquer items that were commissioned from the prestigious English cabinet makers from New Spain.

3.4. Novohispanic Lacquer Screens

Although Chinese lacquer screens circulated widely in New Spain, domestic lacquer screens were undoubtedly more numerous and affordable to larger sectors of the population, as proved by both documentary and material evidence (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Novohispanic lacquer screens.

Table 3.

Novohispanic lacquer screens.

| Novohispanic Lacquer Screen Description |

|---|

| “One lacquer folding screen from China made here.” [45] |

| “Yt another wooden [rodastrado] with lacquer painting.” [46] |

| “Yt one dorm folding screen in black lacquer, two varas and a half high, two tercias wide in cotense, one side, and [with] ten panels for 18 pesos.” [47] |

| “Another rodastrado painted and lacquered in cotense, with twenty panels for 25 pesos.” [48] |

| “Yt one new lacquer screen with ten panels in 25 pesos” and “Yt one rodastrado, ten panels, lacquer, in eight pesos.” [49] |

| “Yt one little rodastrado, 21 panels, into two parts, lacquered, in 10 pesos.” [50] |

| “Another [folding screen] on cotense, two-sided, on one side lacquered, and on the other painted, with ten panels, appraised for 50 pesos.” [30] |

The 1696 reference to the “lacquer folding screen from China made here” is most interesting since it is the only known case where a “screen from China made here” is found. It can be inferred that, unlike most colonial folding screens, this one was actually meant to copy Chinese designs. At this date, Novohispanic lacquer screen production was in its early stages and may not have developed decorative features that differentiated it from the Chinese. The examples of “Criollo lacquer screen” are similar. Criollos are of pure Spanish descent but were born in Spanish America. Unlike Spanish-born individuals, they could not hold the most important political positions, so they felt disadvantaged. The term was sometimes used to refer to anything related to New Spain. In this case, the use of the word Criollo might indicate that Novohispanic lacquer screens were still relatively uncommon in 1708. The making of colonial lacquer screens continued throughout the 18th century, but later references did not refer to the works in the same way.

Among existing Novohispanic folding screens, there are very few that clearly copy Chinese models. Mention should be made, however, of a two-sided screen, whose front depicts the Conquest of Mexico and is signed by Pedro de Villegas in 1718 [

51]. The back of the screen is particularly interesting in this context as it imitates the designs of Chinese lacquer screens, with landscape, architecture, and flowers inspired by them (

Figure 5). Golden clouds borrowed from Japanese screens are included. Despite a few Western details, like a fountain, the resemblance to Chinese models is exceptionally strong.

Documentary references to Chinese screens never mention materials like wood and

cotense (a coarse fabric made of cotton or hemp), so the recording of such materials is a subtle allusion to Novohispanic origin. In Spain, painting techniques—most likely enhanced by varnish—were regularly used to create lacquer-like effects, and in 18th-century Spain, there were lacquer makers who made lacquer coaches and screens, as well as different kinds of furniture pieces. As far as we know, in New Spain, there were no European-style lacquer makers, but in the 18th century, coach makers dabbled in lacquer work, undoubtedly using European techniques [

38] (p. 385). By 1730, Antonio Cuervo, a Mexico City-based coach maker, made a red lacquer cabinet [

15] (pp. 174–176); the fact that the color is the same as most Chinese-style folding screens is noteworthy (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). This suggests an influence from English red lacquer furniture, which was also very popular in Spain in the first half of the 18th century, from where this fashion spread to New Spain.

Due to the lack of information about techniques used in Novohispanic lacquer screens, it is interesting to cite Silvano Acosta Jordan’s comments about chinerías (Chinese-style solutions) in works like altarpieces and processional pedestals from the Canary Islands:

The adaptation or interpretation of the original polychrome designs was a very interesting creative play, since when they were used on altarpieces, frames, lecterns, etc., they were not made following the elaborate original techniques, but using pictorial procedures that had been used in Europe since the Low Middle Ages … in the Canary Islands polychrome techniques, like oil and tempera, are juxtaposed on preparations of lead white or plaster. Over these preparations a background color is applied -organic red or black, mixed with fatty or protein binder prevail. We have seen very few examples of finishings in their original state, since unfortunately their appearance has been misunderstood as aged varnishes, and they have been systematically eliminated… [

52]

Acosta adds, referring to the painting work of an altarpiece by an anonymous artist:

The polychromy is applied on a softwood frame, with simple butt joints reinforced with forged nails. The ground is made of plaster, and a thick layer of organic black is added over it. Depicted motifs were made with a paintbrush, using as a gold powder mixed with protein glue. Drawing was applied very delicately with a paintbrush over the gold, using the same pictorial procedure [

52] (p. 41).

In New Spain, lacquer work was not governed by guilds, which therefore did not interfere with large-scale production. Could it be possible that Villegas and other painters made screens that were painted on one side and lacquered on the other? In fact, Villegas’ work recalls the 1737 reference to a folding screen that was “on one side lacquered, and on the other, painted”. Of note are Romero de Terreros’ comments about:

A folding screen painted with oil on canvas [which] imitated on one side a Coromandel lacquer screen so masterfully made, that only up close and by touching one would know that it was not made with a lacquered panel but with painting on canvas. At the center of a multitude of typical Chinese decorative motifs a big medallion stood out, populated […] by European figures […] but interpreted with an Oriental criteria […] the fact that the folding screen was made in New Spain is fully demonstrated in the front, where a distinctly Mexican scene is depicted. It is therefore evident that the anonymous painter could view an authentic Chinese screen which he copied on one side, while he executed the other side freehand [

53].

Although Novohispanic lacquer folding screen production lasted through the 18th century, there is no evidence that their popularity resulted in artists who specialized in them. Ordering a different artist to decorate each side would have led to a price jump. The price of 50 pesos for a ten-panel folding screen “on cotense, two-sided, on one side lacquered, and on the other painted” is relatively high but by no means exceptional in the Novohispanic context. The fact that the folding screen was made with fabric—even on the lacquered side—suggest that it was made in a painting workshop.

We do not know how often folding screens would be made in the workshops of Michoacán and Guerrero. Except for the reference from Tardes americanas, there is no evidence that folding screens would be part of their regular production. These workshops would regularly be involved in the production of bateas, sewing boxes, or small pieces of furniture. As we have seen, the making of Novohispanic lacquer screens started several decades before De la Cerda’s work. Therefore, lacquer screens from Pátzcuaro would be just one part of the Novohispanic production of lacquer screens.

The prices of Novohispanic lacquer screens varied from between 8 and 25 pesos. This points to quality differences, probably derived from the fact that there were different workshops involved in this kind of work. Although price differences in Chinese screens are even more noticeable, the market for Novohispanic works was not necessarily a low-income one: in 1737, wealthy José del Barrio, Knight of the Order of Santiago, who owned many Asian objects, had one folding screen “on

cotense, two-sided, on one side lacquered, and on the other painted, with ten panels, appraised for 50 pesos” [

30]; undoubtedly it had been made in New Spain. The fact that even those who could afford original Chinese works had Novohispanic screens suggests that the latter were appreciated. Differences between Asian and Asian-inspired screens are easily noticeable. Therefore, Barrio’s screen, as that signed by Villegas, suggests that privileged individuals were not only fond of Chinese art but also of Novohispanic objects that took Asian art as a starting point to make proposals of their own.

3.5. Imitation Lacquer- and Chinese-Style Novohispanic Screens

If the existence of Novohispanic lacquer screens has raised doubts about the techniques used and the workshops where they were made, the topic becomes even more complex regarding imitation lacquer screens. In Spain and other European nations, there are references to works of “genuine lacquer” (‘

de charol legítimo’) and others “imitating lacquer” (‘

contrahechas de charol’); “genuine lacquer” refers to Far Eastern Asian lacquer [

38] (p. 172), while “imitation lacquer” would likely refer to works of different origin [

38] (p. 233). The data in

Table 4 suggests that the case was a little more complex in New Spain:

Table 4.

Imitation lacquer Novohispanic screens.

Table 4.

Imitation lacquer Novohispanic screens.

| Imitation Lacquer Screen Description |

|---|

| “One new imitating lacquer screen [fingido de maque] for 25 pesos.” [54] |

| “One good rodastrado, with eleven panels, imitating lacquer, white [de maque blanco fingido], appraised for 15 pesos.” [2] (p. 27) |

| “One Chinese-style and imitating lacquer [achinado y maqueado fingido] rodastrado, 24 panels, one vara high, for 80 pesos.” [55] |

Differences between Novohispanic imitation lacquer and lacquer screens are not clear from these descriptions. Not only do both kinds of screens date from the same years but also, some imitation lacquer screens were said to be of good quality and cost the same as lacquer screens, which suggests that the imitation lacquer screens were appreciated as much as the lacquer ones. The reference from 1732 is particularly noteworthy since it records the highest price for a Novohispanic lacquer screen. This is partly because the work had 24 panels. But even so, the price is not much lower than that of “one lacquer

rodastrado from China, with 23 panels, one

vara and a half high, appraised for 115 pesos” [

33], which in 1695 was listed in the asset of the wealthiest Marchioness of San Jorge.

The Chinese style and imitation lacquer

rodastrado from 1732 also stands out because it is mentioned in the dowry letter of the first marriage of the prominent Count of Santiago Calimaya, which allows us to suppose that this kind of work came to be highly appreciated. Although the color is not mentioned, the work might have been similar to a

rodastrado that first came to light in 1970 (

Figure 6); it was divided into two parts, each consisting of six leaves [

1] (pp. 83–86). It was only later discovered that they had previously been joined [

32] (p. 92). Both sections are closely related to one another, each showing different sites in Mexico City. This is a noteworthy work that appears to have been made in a painting workshop; however, the red background imitates Chinese lacquer screens, as do the long-tailed birds inspired by the

feng-huang.

The reference from 1720 of one “good

rodastrado, with eleven panels, lacquer-like, white, appraised for 15 pesos” is indicative of the role of European lacquer in the development of Novohispanic lacquer screens. As already mentioned, white lacquer was first developed in Europe and was used in screens in Spain, like the “lacquer screen with eight leaves, the background in the color of pearl shaded with different figures, and flowers cut in paper, two-sided, every leaf is one foot and nine fingers wide, six and six height” [

38] (p. 392) which belonged to Isabella Farnese. An exceptional reference from 1769 to “two long boxes unnumbered and unmarked which contain two white lacquer screens each with twelve leaves” [

4] (p. 37), appraised for 25 pesos each, is also of interest. These works had been shipped from Canton to Manila [

4] (p. 37). The fact that it is a highly unusual work shipped to a Spanish port in Asia at such a late date allows us to posit that Chinese white “lacquer” screens were produced to satisfy Spanish American demand [

56]. However, true Chinese lacquer of this period could not be made in white, so these pieces would likely have a polished chalk or other white background.

That said, in Europe and the Americas, lacquer work was sometimes passed over or called “painting”. In New Spain, this happened with Chinese as well as Novohispanic works [

15] (p. 147). For this reason, it is difficult to know if some of the screens that the sources refer to as “Chinese style” were made in the same workshops that made the lacquer ones. But, regardless of the technique, they undoubtedly were part of the large group of Novohispanic works that were developed from Chinese lacquer screens. Nonetheless, screens were not the only works that documents describe as “Chinese style”. On the contrary, many Novohispanic documents mention Chinese-style boxes, stools, tables, and wardrobes. These works would likely have been made in different kinds of workshops, and “Chinese style” would not relate to a certain technique but to certain effects achieved through different procedures.

The adjectives used in several of the references in

Table 5 suggest a low quality: “old” (unlike “ancient”, which is preferred for works that are appreciated despite their age), “already used”, and “ordinary”. Recorded prices are lower than those of lacquer and imitation lacquer screens. However, not all the works were considered as merely substitutes for good quality work; references to one “12-panel

rodastrado, one

vara and one

tercia high and two

tercias wide”, with Chinese-style painting and a “one-

sesma crest, of fake gold … for 25 pesos” and to “one Chinese-style screen of gold, two-sided, 29 pesos” suggest a work like the one we have discussed before.

Table 5.

Chinese-style lacquer screens.

Table 5.

Chinese-style lacquer screens.

| Lacquer Screen Description |

|---|

| “Yt one Chinese-style screen of about ten panels, old, for 7 pesos.” [57] |

| “One rodastrado of twelve panels, one vara and one tercia high and two tercias wide, painted in Chinese-style and a one-sesma crest, of fake gold … for 25 pesos.” [2] (p. 28) |

| “Another said [screen] Chinese-style, of 8 panels, for 10 pesos.” [2] (p. 28) |

| “One screen, two-sided, Chinese-style, two varas and one tercia high, mistreated, for 20 pesos.” [2] (p. 29) |

| “[One screen], two-sided, of raw [fabric], Chinese-style painting.” [30] |

| “Yt one Chinese-style screen, red, old, for 7 pesos.” [58] |

| “One rodastrado with twelve panels, already used, painted in the manner of China over red with a wide golden frame, on raw cotense, for 14 pesos.” [59] |

| “Two Chinese-style screens, ordinary, two varas high; one mistreated, for 7 pesos.” [2] (p. 32) |

“For one Chinese-style screen of gold, two-sided, 29 pesos”.

“For one ordinary screen, Chinese-style, 5 pesos.” [26] (p. 237) |

| “One red Chinese-style rodastrado … for 10 pesos.” [36] |

Even so, it is interesting that some Chinese-style screens are said to be “ordinary”. These works were undoubtedly made in less well-known painting workshops. They must not have been commissioned but made for the open market. Since these works are lost, their details are unknown. Either way, this segment of production suggests that, although the phenomenon of Chinese lacquer screens was originally reserved for the highest income groups, by the end of the 18th century, it had extended to less wealthy Novohispanic society.

Some screens are not only said to be Chinese style but also red. These would likely be similar to the ones we previously discussed, except for the use of varnish and the lacquer-like finish. It is also noteworthy that some documentary references mention red screens without referring to the lacquer or the Chinese or Chinese-style screens. This kind of work can be seen on several screens; for example, the “screen of the nations” of the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City (

Figure 7), the Otto van Veen’s emblems screen at the Dallas Museum of Art, and the screen with views and landscapes exhibited in the International Museum of the Baroque in Puebla. In the same manner, as all the aforementioned screens, the red ones were significantly varied in terms of quality. The fact that many red screens were made, which were otherwise totally unrelated to lacquer screens, demonstrates that once the taste for red Chinese-style screens had developed, there were so many variations that, in some cases, the Asian influence eventually disappeared.

4. Discussion

From the late 16th century, New Spain had a direct relationship with Asia, which led to the desire for screens to become a local fashion more than any other place outside of Asia. By 1700, European lacquer and generally the fashion for chinoiserie had expanded to the Americas and had an impact on Novohispanic lacquer screens, which makes them a good case study of the role that New Spain played in the artistic globalization of the period.

The lacquer phenomenon of the 17th and 18th centuries was very widespread due to the existence of many techniques. This is particularly true regarding lacquer screens circulating in New Spain in the 18th century. As we have seen, the first pieces to be known were Asian, mainly Chinese; some of them were adapted to Novohispanic taste, while others were similar to those circulated in other Western nations. European screens occasionally circulated as well. But it was Novohispanic screens that made this phenomenon so complex, since there were so many procedures involved, different types of workshops, and production centers, that their technique is impossible to know a priori.

This does not mean that we should give up trying to identify such techniques. On the contrary, most lacquer objects and small pieces of furniture were made in regional workshops, whose techniques are being increasingly understood. Comparing their technique with that of Novohispanic lacquer screens will be key to understanding the true scope of the lacquer phenomenon in New Spain. Comparing the procedures used in different works, such as the folding screen of the viceroy’s entry that is believed to have been made in Pátzcuaro, the screens in the Franz Mayer Museum, and the ones in the Museum of Fine Arts of Houston and the Dallas Museum of Art will allow us to answer the following questions: were the lacquer techniques used for screens the same as in other objects? In what kind of workshops were they made? To what extent were painters involved in their making?

Unless future studies demonstrate otherwise, Chinese-style and red screens are likely to have only been occasionally made in regional lacquer workshops. Regarding this, it is interesting that Granados y Gálvez wrote that the lacquer from Michoacán was mostly black [

16] (p. 117). Actually, very rarely do existing lacquer pieces from Michoacán have a red background.

Novohispanic lacquer screens do not result from a passive reception of Asian models since they go far beyond merely copying them. Moreover, the Asian works were themselves shaped to meet local tastes. This is a topic for future studies: although New Spain was the location where Asian screens were more successful outside of Asia, the features of those screens still are poorly known.

The circulation of Chinese lacquer screens in New Spain coincided with the arrival of European lacquer. In Madrid, lacquer screens were being made from at least 1680, so it is conceivable that some Novohispanic lacquer screens relate to European ones. While in Europe, different lacquer techniques were developed, variety was much noticeable in New Spain, where there were lacquers made with European procedures, as well as regional ones of pre-Columbian origin and painting techniques imitating lacquer, all of which were sometimes used to make folding screens.

The consequences of this variety are yet to be fully assessed. Novohispanic historiography repeats the concept that Asian art was related to luxury, although it has been demonstrated that it was not always the case. Chinese silk could be actually cheap [

60], and the same is true for porcelain. As we have seen, Chinese lacquer screens were at one time expensive and indeed related to luxury. But their circulation encouraged many local centers of production, some of which served several social classes. At the same time, even though the technique and palette of European lacquer, and especially of European lacquer folding screens, exerted a significant influence over Novohispanic lacquer screens, the latter followed their own artistic paths, totally unrelated to the foreign examples.