Three Studies of Luxury Mexican Lacquer Objects from the 16th to the 19th Centuries, Analysis of Materials and Pictorial Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

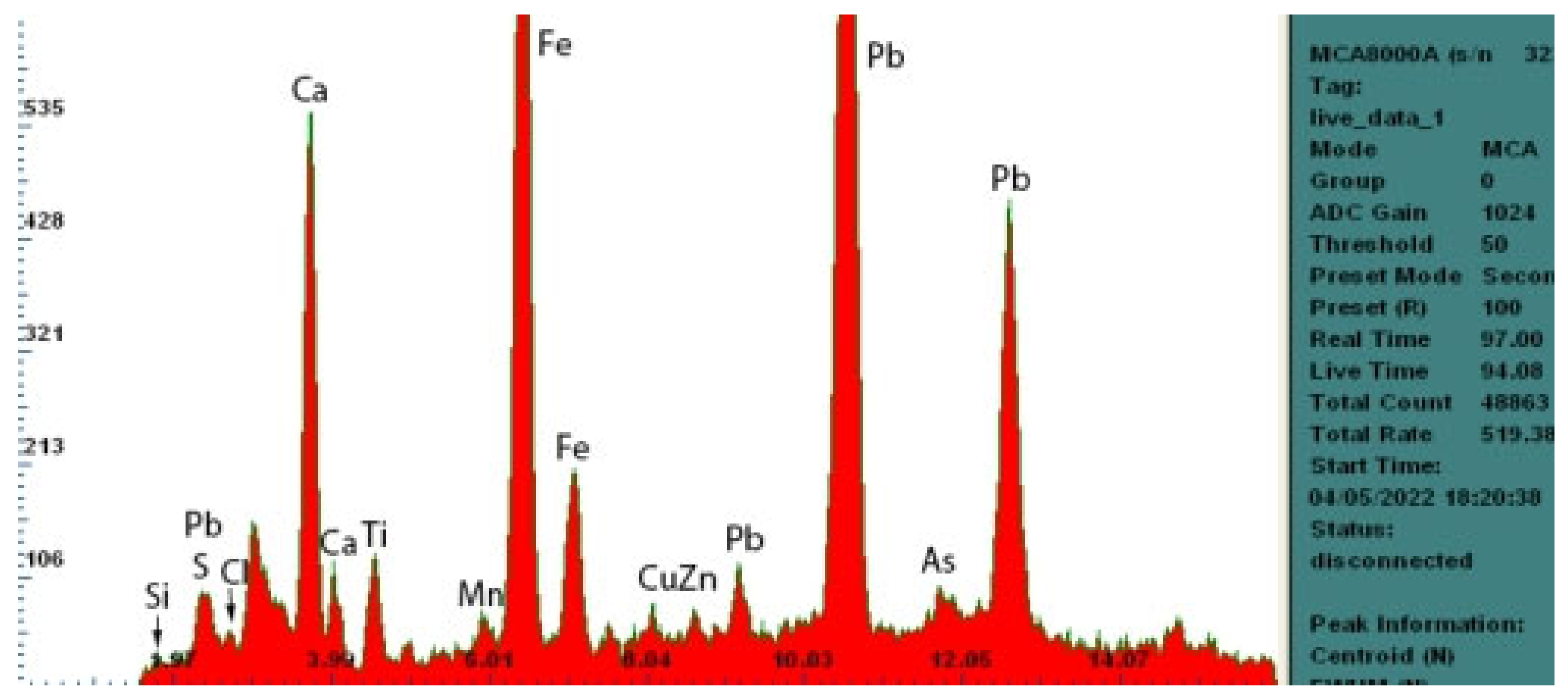

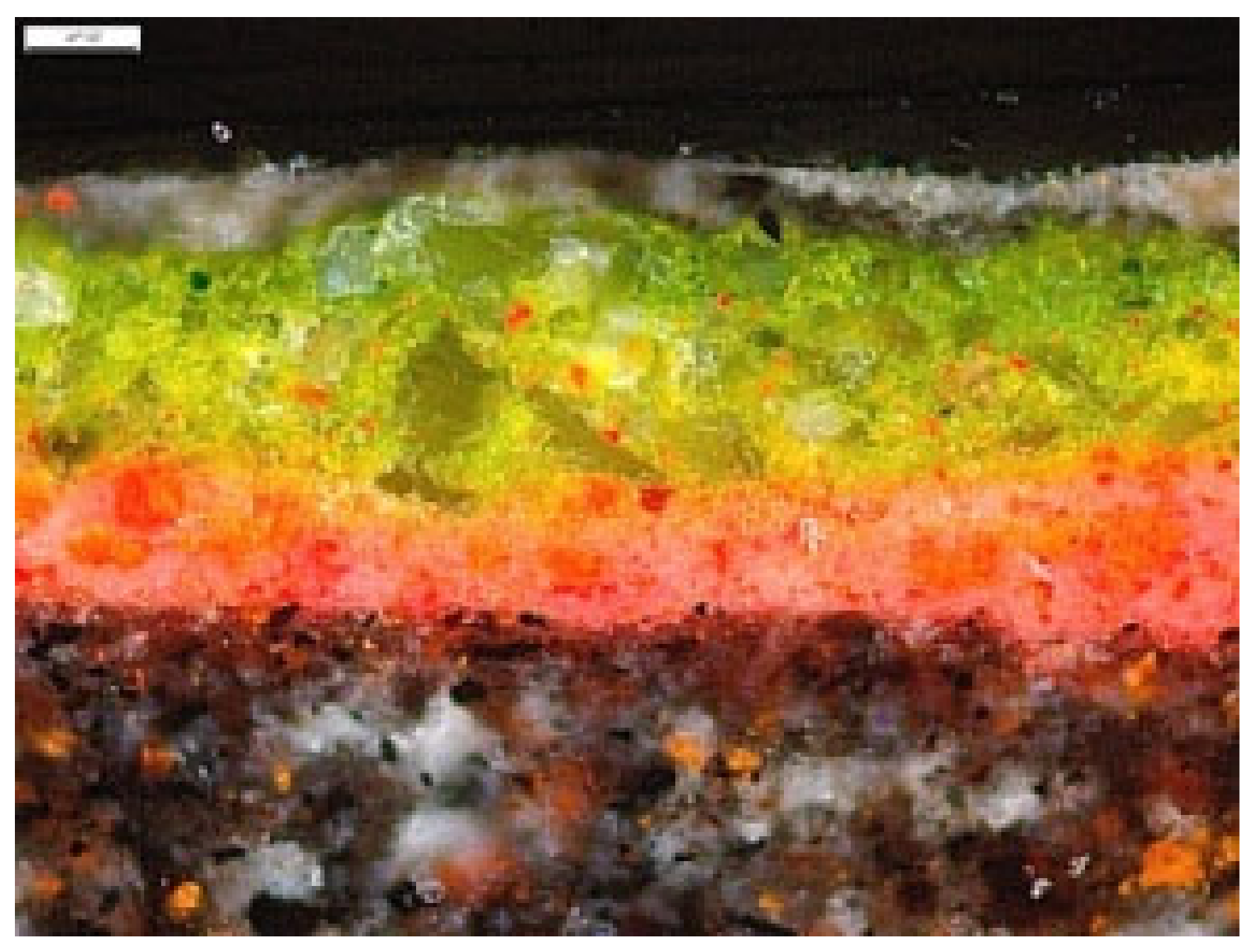

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

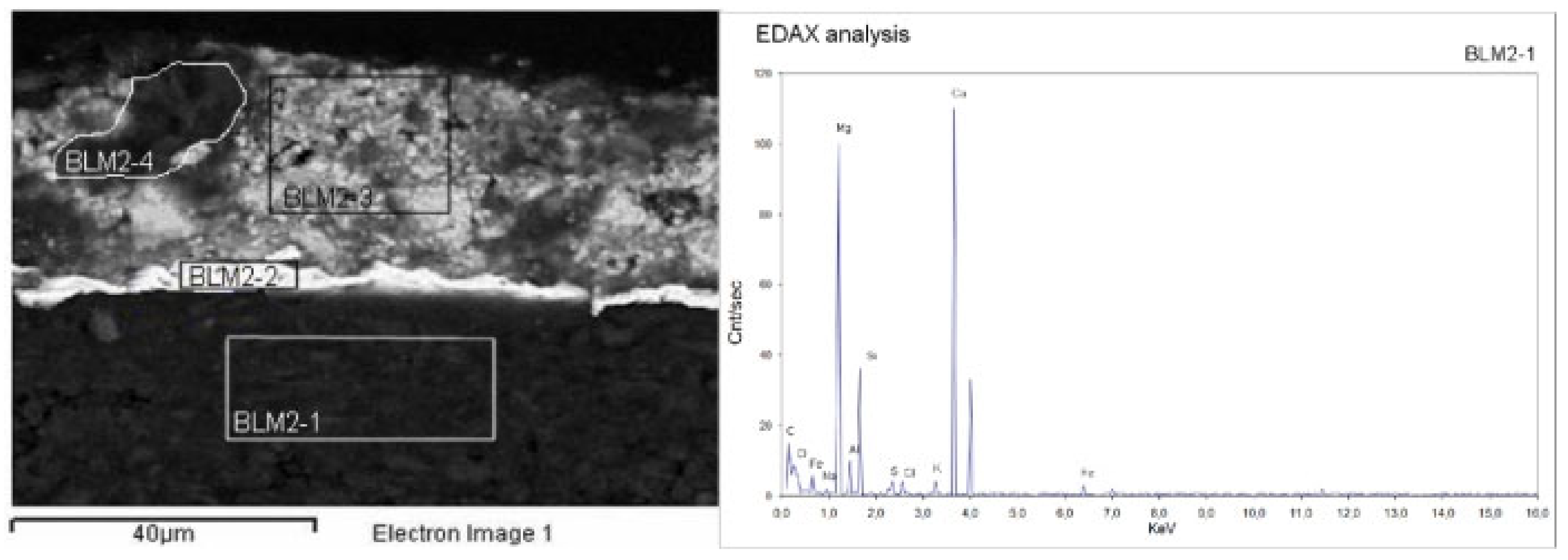

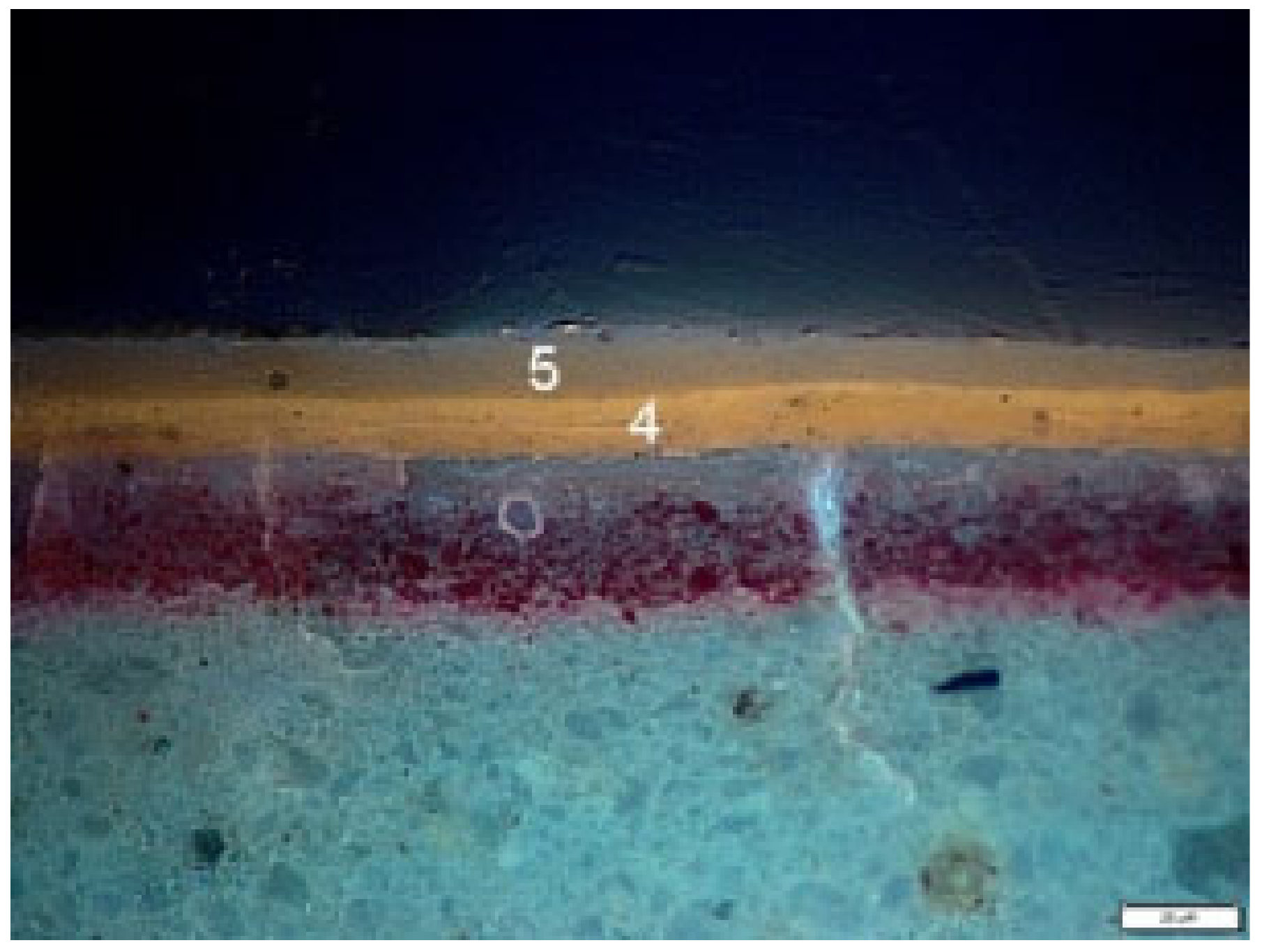

3.1. The Beginnings of the Novo-Hispanic Lacquer Objects

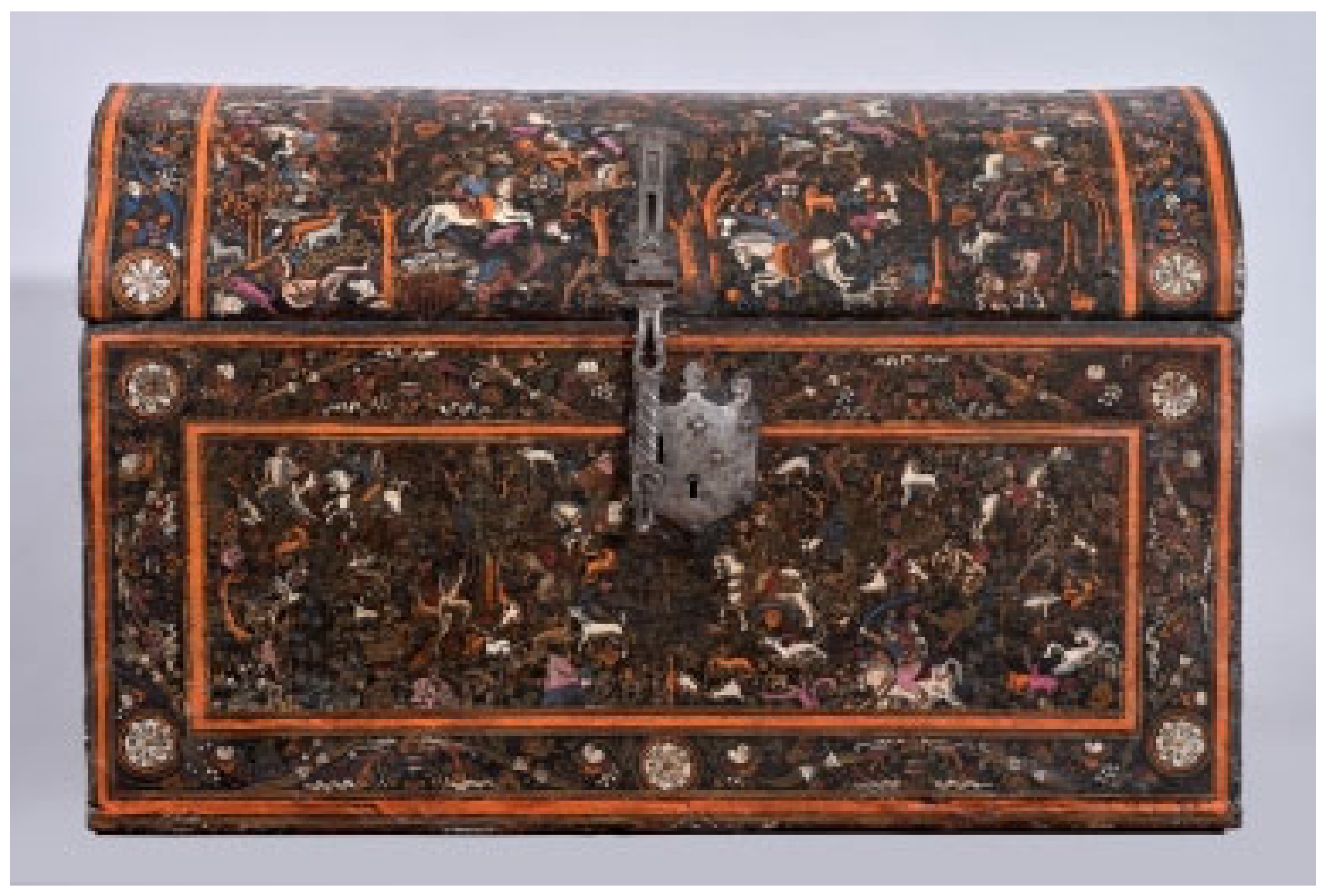

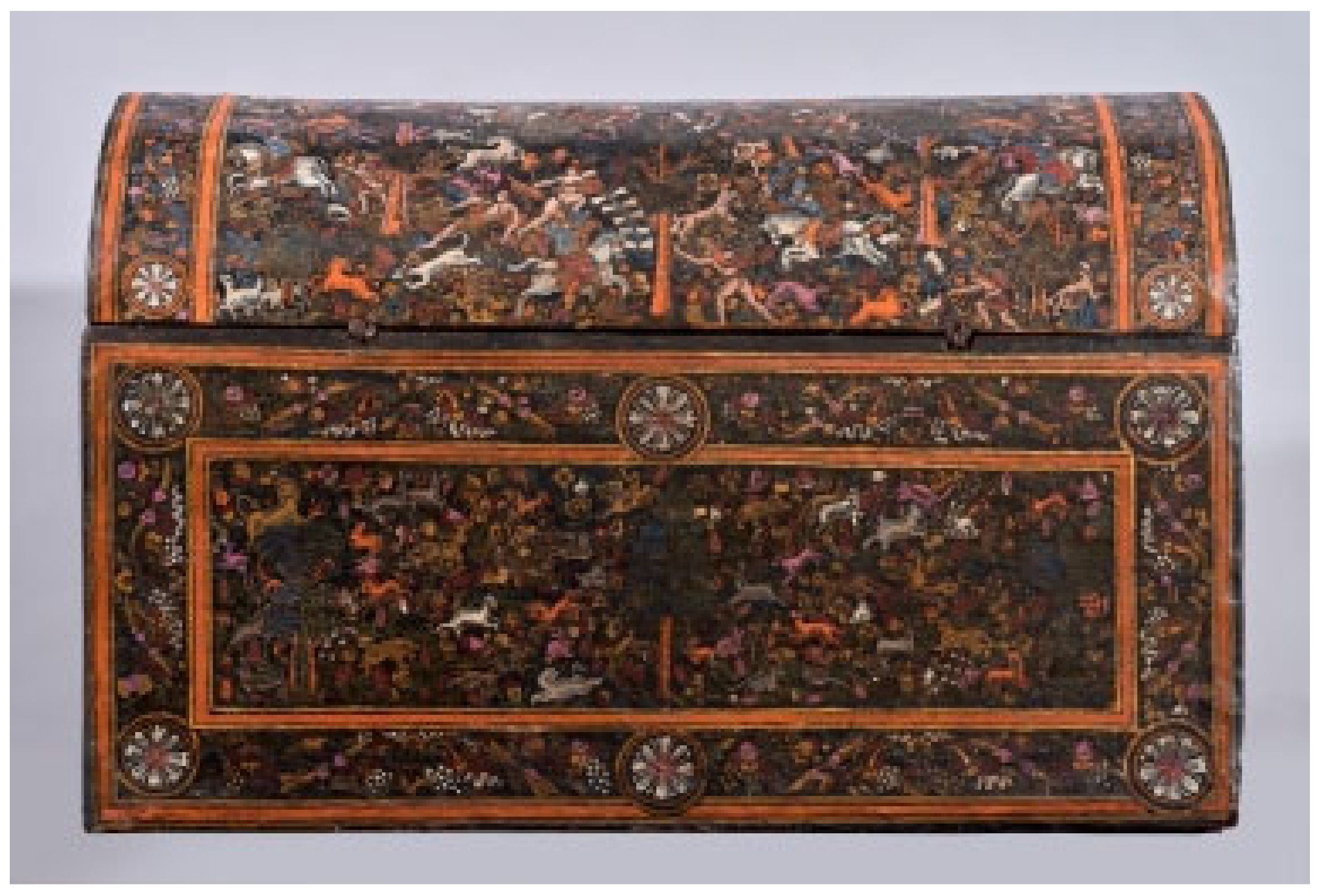

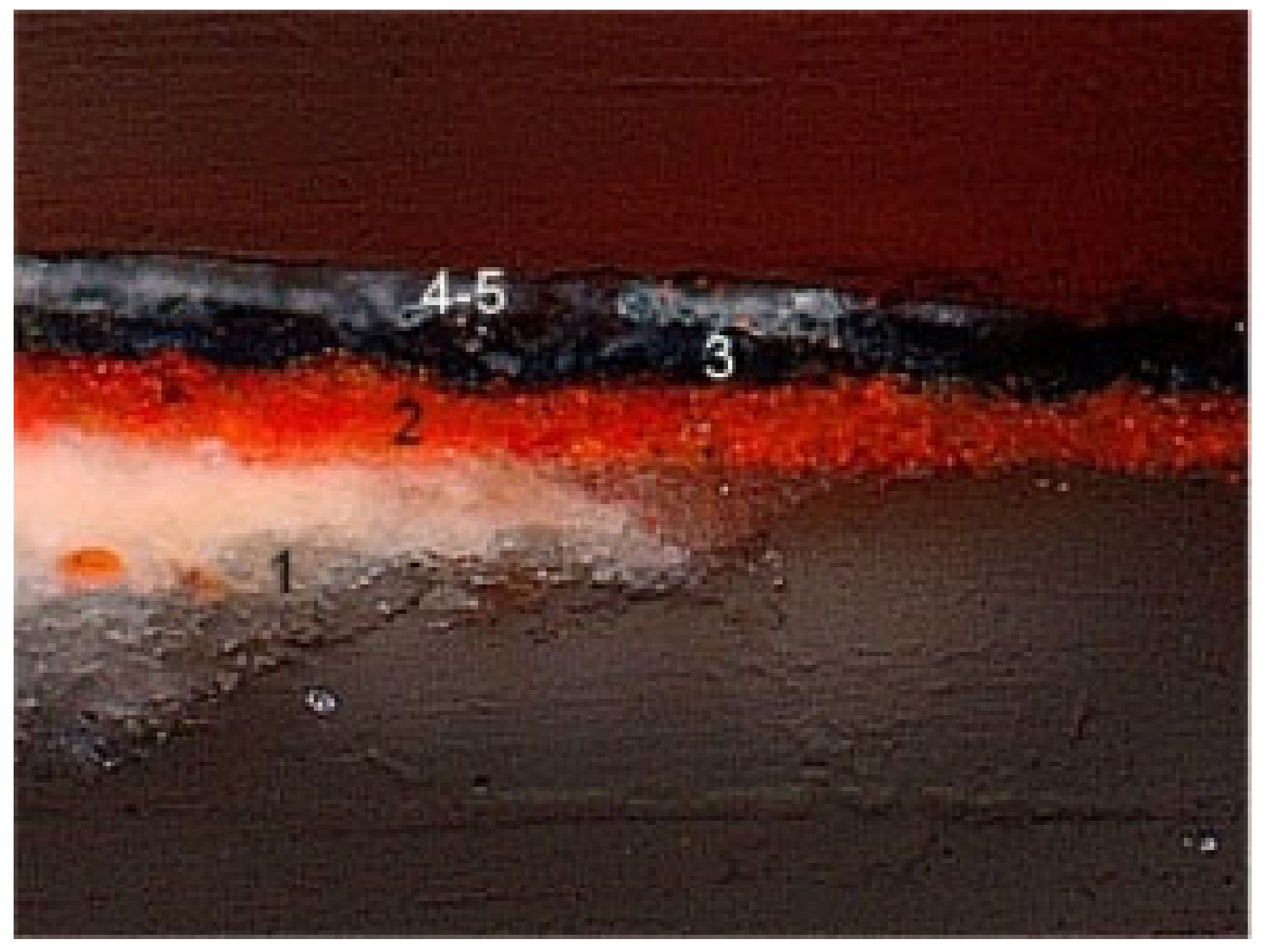

Chest Decorated with Plant Motifs, Mythical Animals and Hunting Scenes, Peribán Style, Third or Last Quarter of the 16th Century, Lacquered Wood, Polychromed Interior, Original Iron Lock and Handles

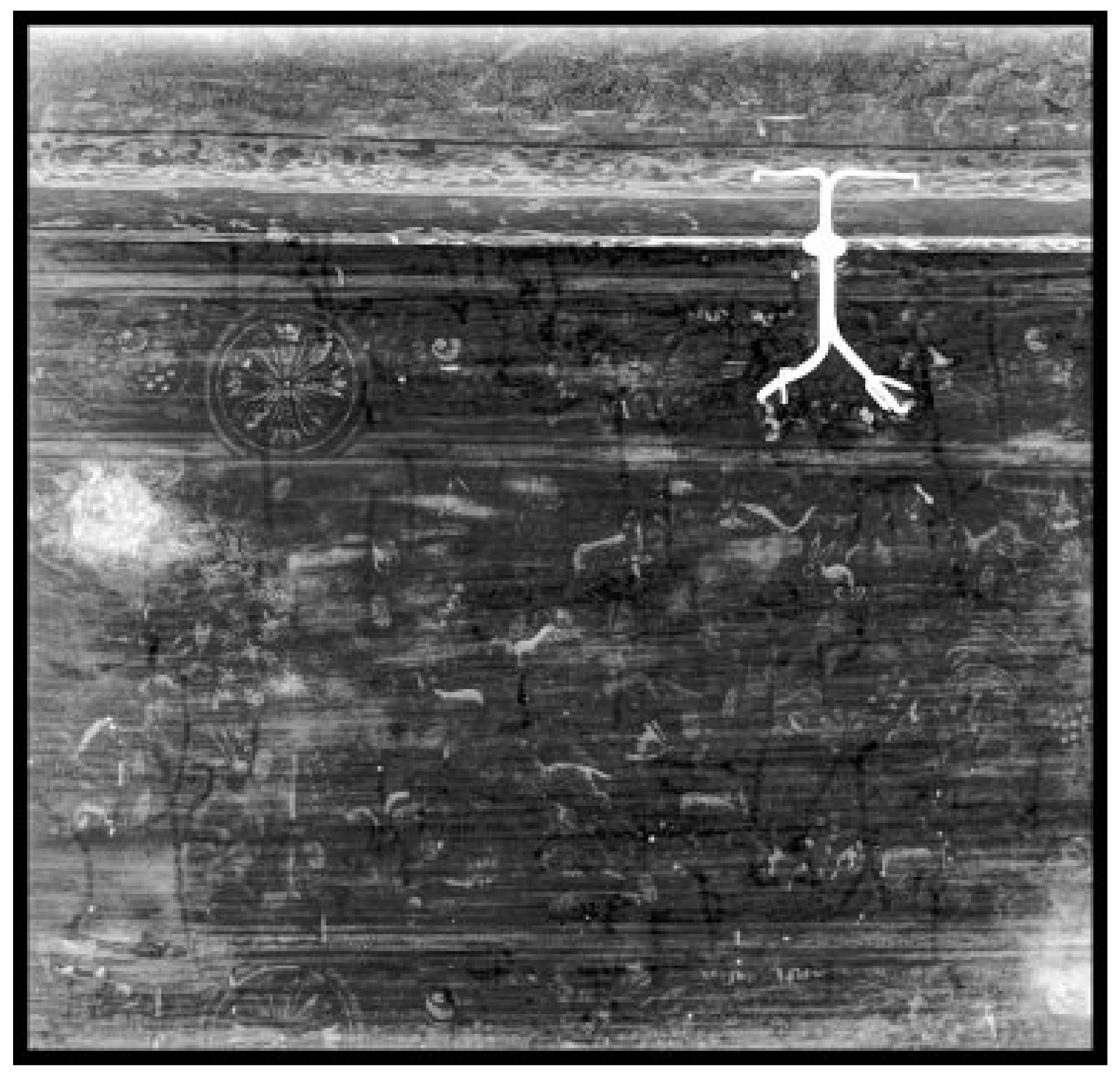

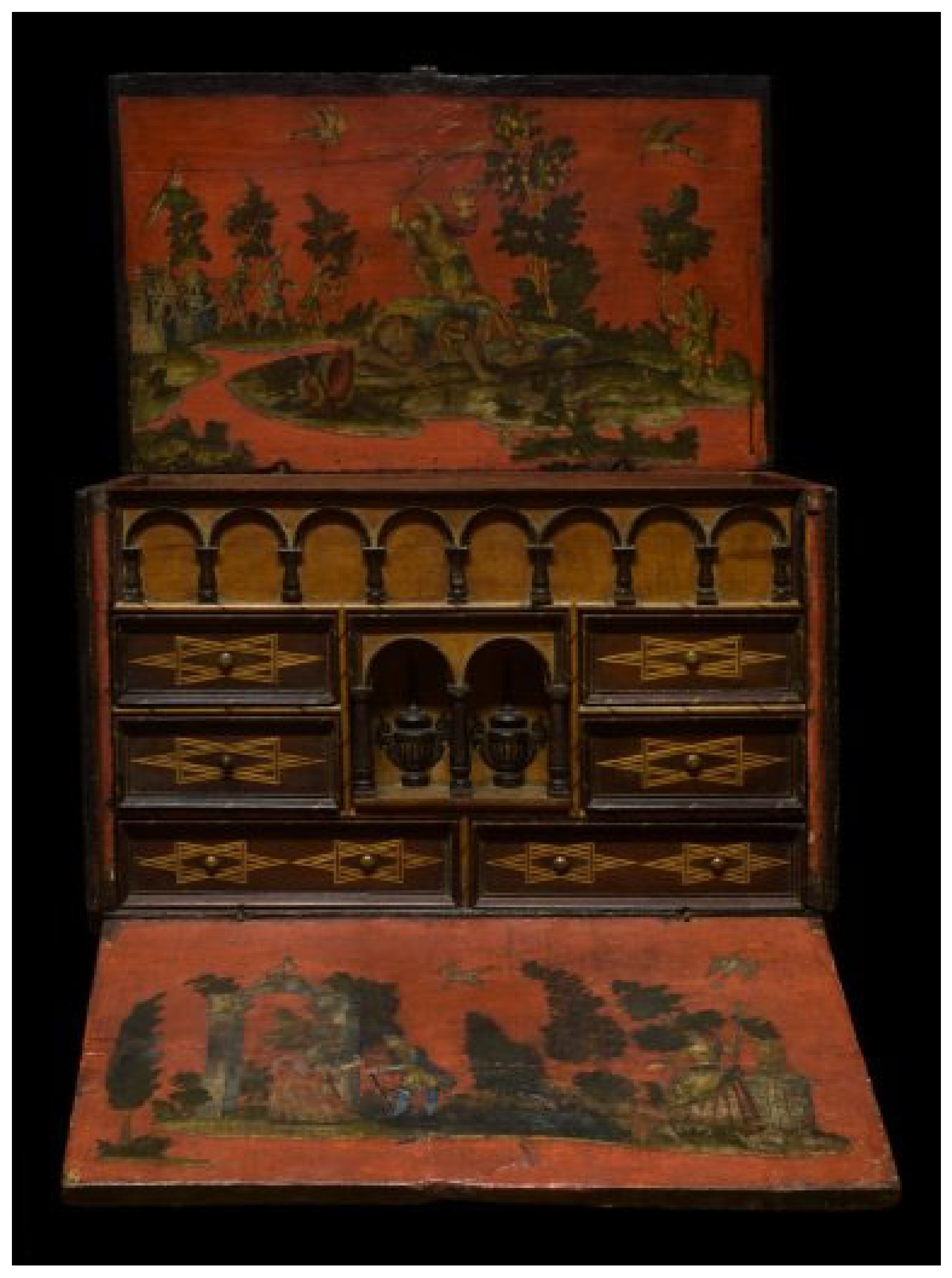

3.2. Evolution to the European Rococó Style

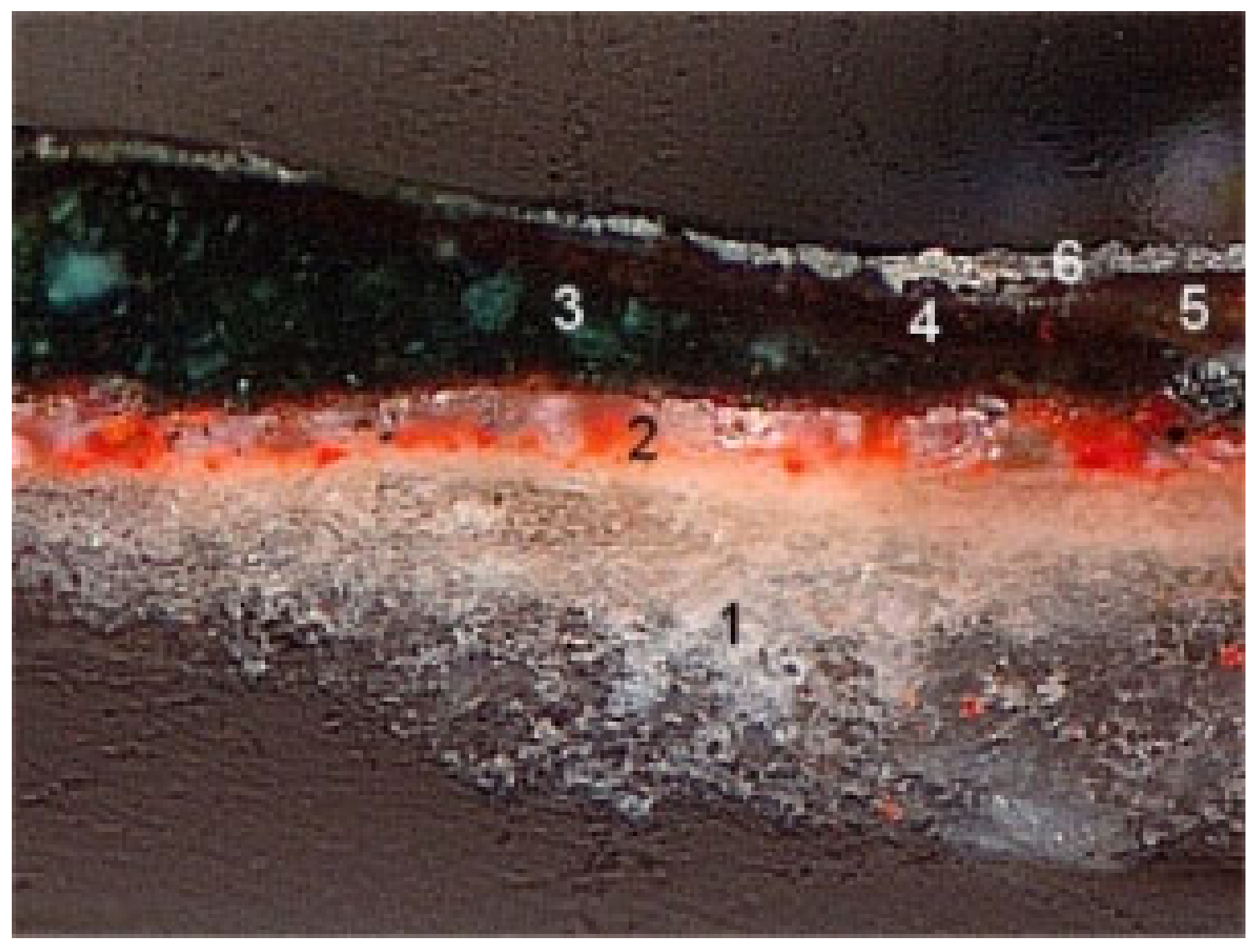

Portable Desk Decorated on the Inside with Scenes of David and Goliath and a Courtly Theme, Mexico, 18th Century

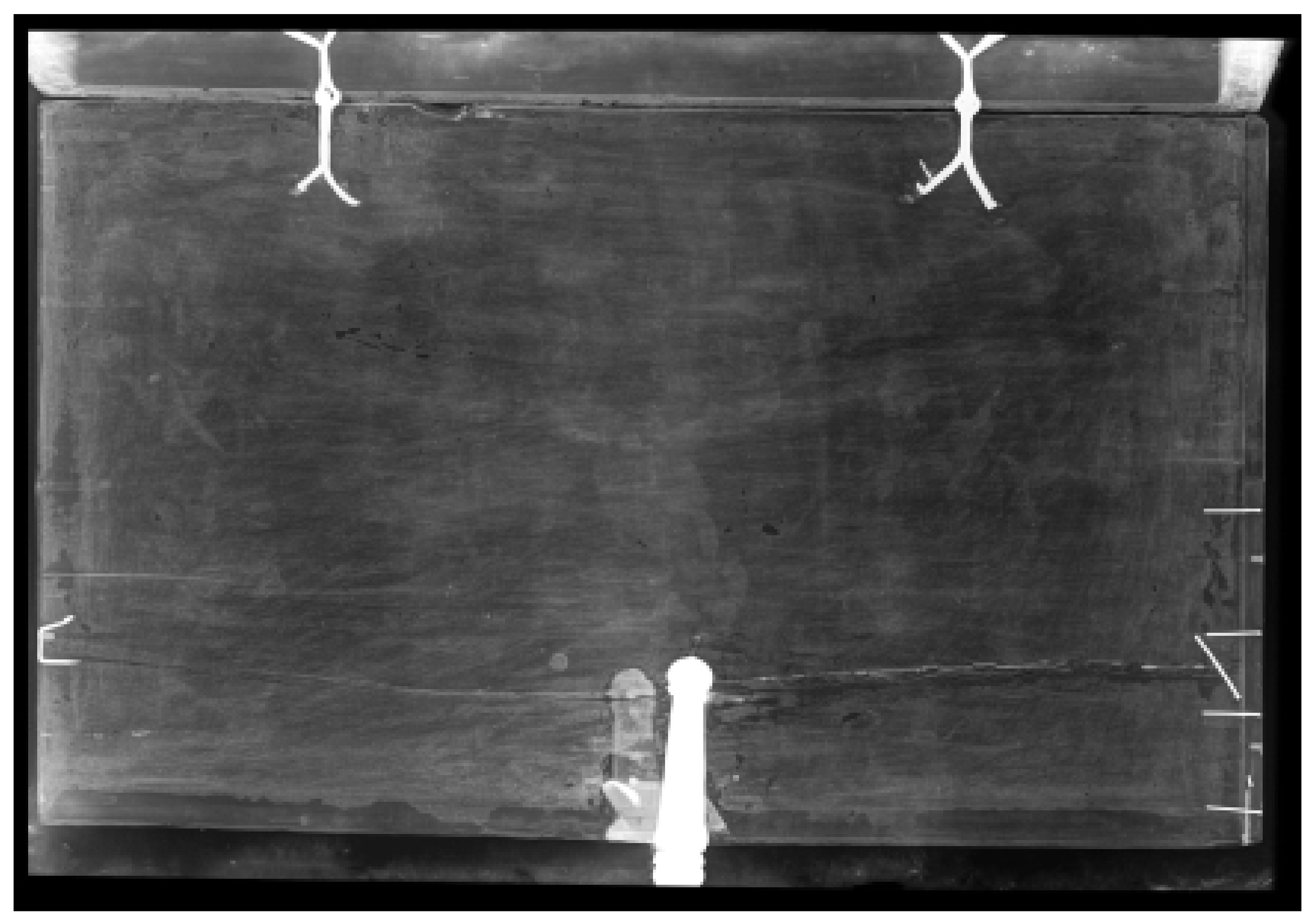

3.3. Survival and Innovation in Lacquer Techniques

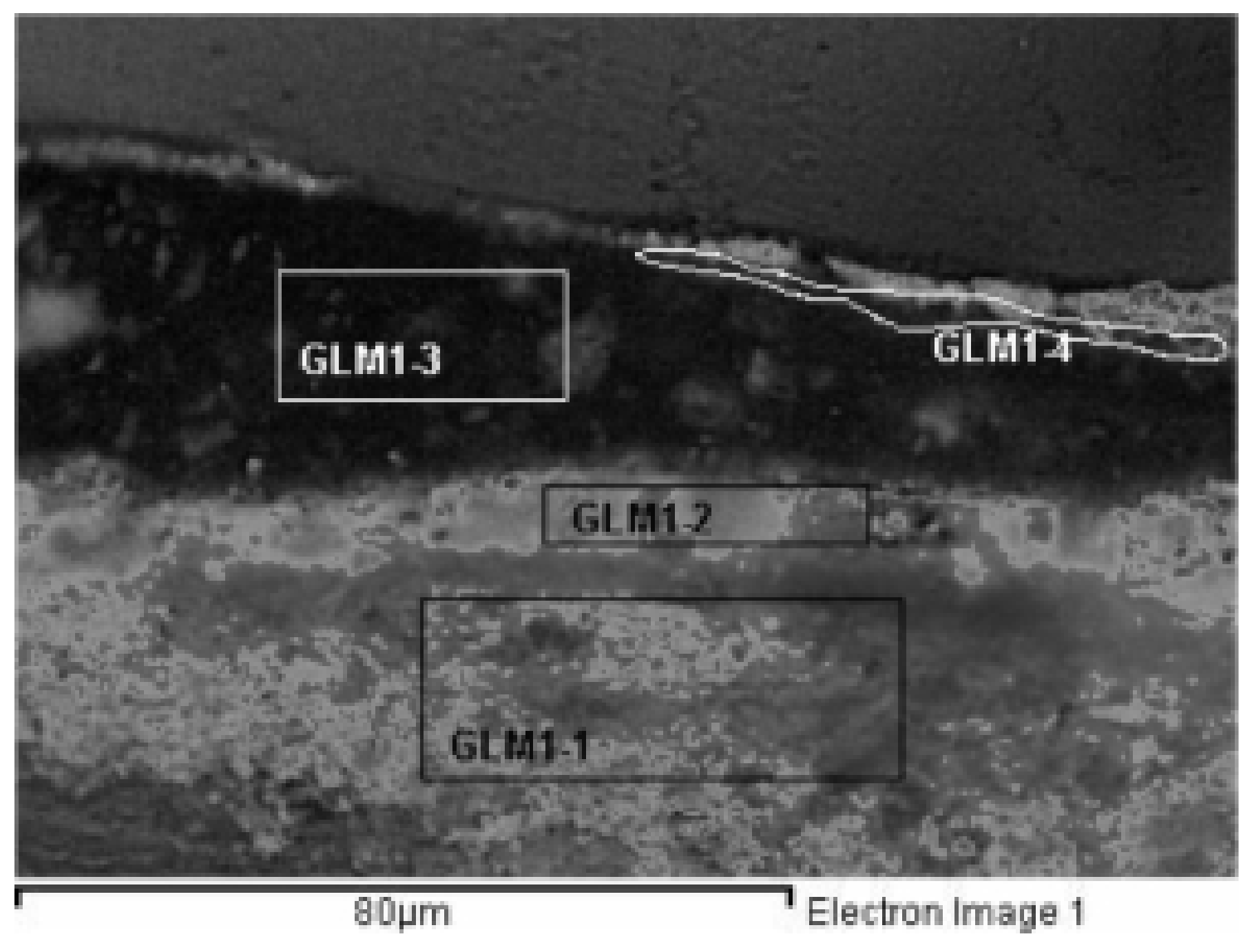

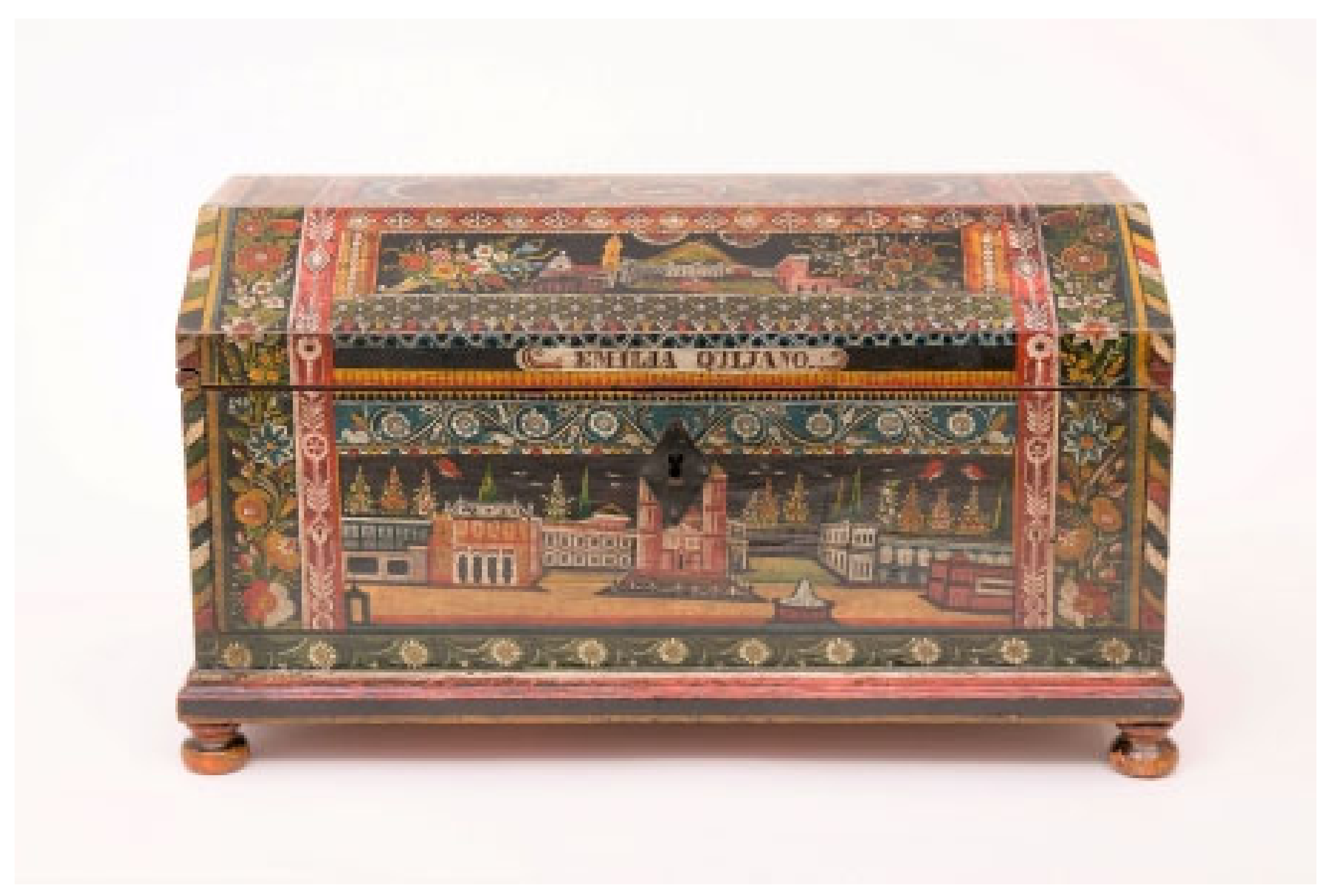

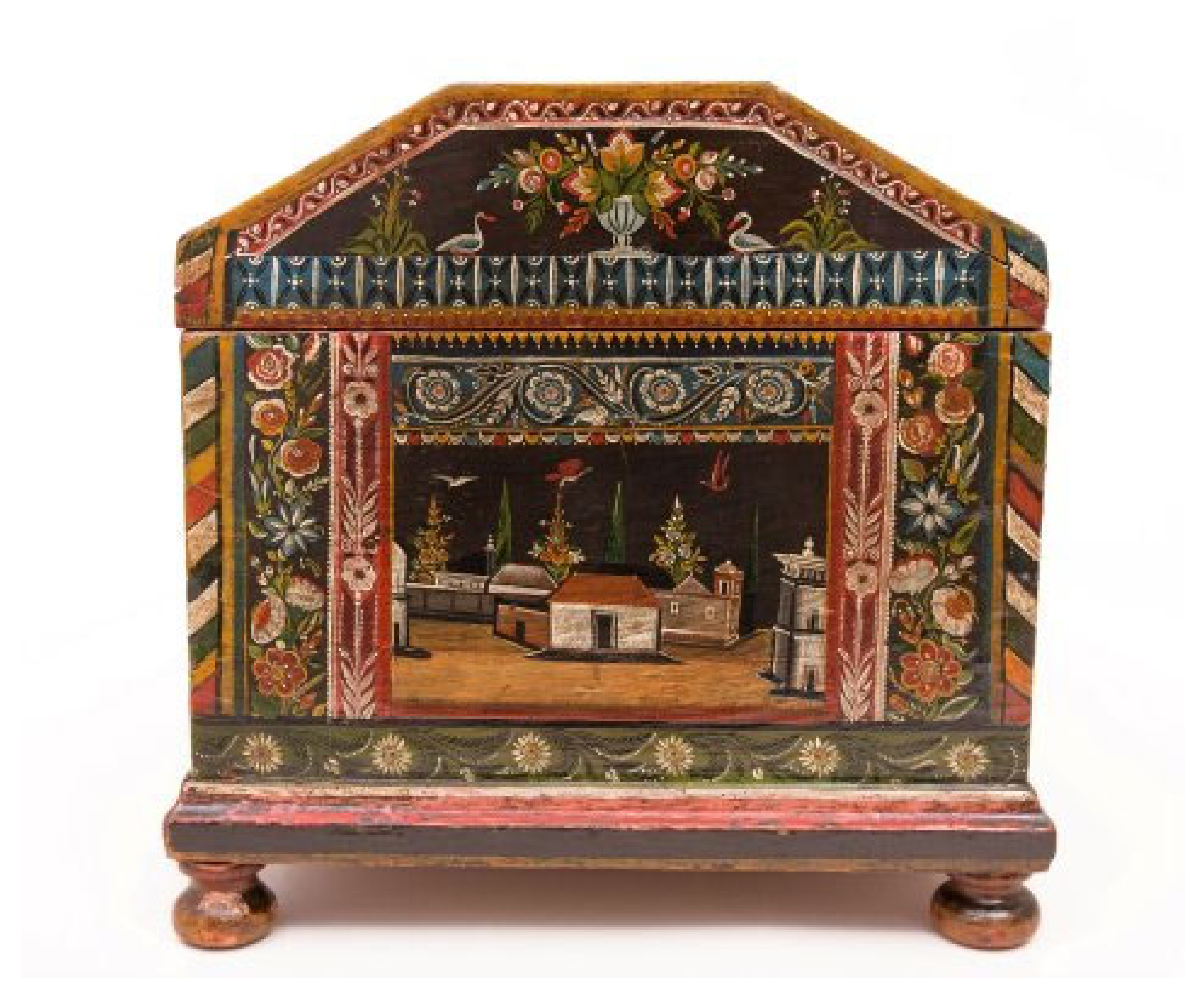

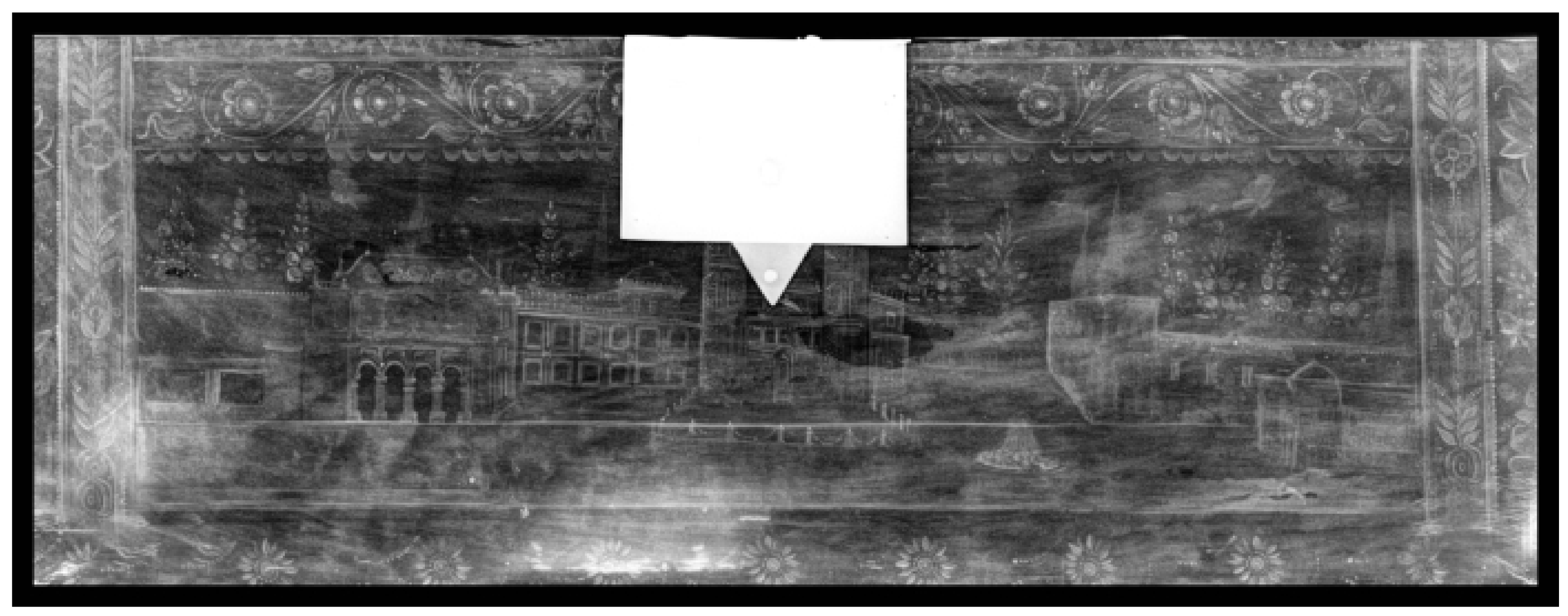

Olinalá Chest with Decorations of Garden City Views and Floral Arrangements, 19th Century, Ownership Inscription: Emilia Quijano and Dated: Sta Rosa 1874

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ocaña, S. Laca. Color y Brillo Novohispano; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Orellana, M. Mexican Lacquers. Collection, Use and Style, Franz Mayer Museum; Artes de Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña Castrellón, P.E. El Maque o Laca Mexicana; El Colegio de Michoacán, Fideicomiso Felipe Teixidor y Montserrat Alfau de Teixidor: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán Contreras, A. Las Lacas; Fondo Nacional para el Fomento de las Artesanías: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Carrillo, S. La Laca Mexicana. Desarrollo de un Oficio Artesanal en el Virreinato de la Nueva España en el Siglo XVIII; Alianza Editorial; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- De Cantú, G.R. Supervivencia de un Arte. In El Arte en el Comercio con Asia; Artes de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1976; Volume 190, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- González, I.M. Técnicas Pictóricas de Jícaras y Guajes Prehispánicos. Available online: https://docplayer.es/114902815-Tecnicas-pictoricas-de-jicaras-y-guajes-prehispanicos-isabel-medina-gonzalez-cnrpc-inah.html (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo. Catalogue of the Exhibition. Mueble Español. Estrado y Dormitorio; Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo: Madrid, Spain, 1990; p. 106.

- Toussaint, M. Pintura Colonial en México; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1990; pp. 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Almansa Moreno, J.M.; Martínez Jiménez, N.; Quiles García, F. Pintura Mural en la Edad Moderna Entre Andalucía e Iberoamérica; Universo Barroco Iberoamericano: Sevilla, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IIC Spanish Group. Online Course Lacquers of the World. History and Technique; IIC Spanish Group: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.S.; White, R. The Organic Chemistry of Museum Objects; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 1994; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://arche.cnrs.fr/research_projects/chia-oil/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Suazo-Ortuno, I.; Del Val de Gortari, E.; Benitez-Malvido, J. Redescubriendo un insecto extraordinario que desaparce: Llaveia axin axin. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2013, 84, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/31805/2008_03_185_190.pdf;sequence=1 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Burns, M.R.; Mosquera, S.M.; Whitmore, L.J. Useful Trees of the Tropical Region of North America; Publication No. 3; North America Forestry Commision: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña Ruiz, S.I. De Asia a la Nueva España vía Europa: Lacas Asiáticas y Achinadas en el Siglo XVIII; Anales Instituto Investigaciones Estéticas: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017; Volume 39, pp. 131–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Miyakoshi, T. Laquer Chemistry and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Konthe, F. An Unbroken History. Conserving East Asian Works of Art and Heritage; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, S.; Faulkner, R.; Pretzel, B. (Eds.) Laquer: Technical Analysis and Conservation. Incorporating postprints from the lacquer session of the IIC Hong Kong Congress 2014, IIC London 2015. In East Asian Laquer; Material Culture, Science and Conservation; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://carapan.com.mx/blogs/mexican-folk-art-techniques-tradditions/52888644-maque-rediscovering-an-almost-lost-pre-columbian-technique (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- De la Mata, A.Z. El arte del barniz de pasto en la colección del Museo de América de Madrid. An. Mus. América 2020, 81–98. Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/museodeamerica/dam/jcr:fbf666e8-f20e-481c-96c9-16f9c7e5dc16/06-anales-del-museo-de-america-xxviii-2020-zab-a-81-98.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero, R.; Illán, A.; Bondía, C. Three Studies of Luxury Mexican Lacquer Objects from the 16th to the 19th Centuries, Analysis of Materials and Pictorial Techniques. Heritage 2023, 6, 3590-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6040191

Romero R, Illán A, Bondía C. Three Studies of Luxury Mexican Lacquer Objects from the 16th to the 19th Centuries, Analysis of Materials and Pictorial Techniques. Heritage. 2023; 6(4):3590-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6040191

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero, Rafael, Adelina Illán, and Clara Bondía. 2023. "Three Studies of Luxury Mexican Lacquer Objects from the 16th to the 19th Centuries, Analysis of Materials and Pictorial Techniques" Heritage 6, no. 4: 3590-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6040191

APA StyleRomero, R., Illán, A., & Bondía, C. (2023). Three Studies of Luxury Mexican Lacquer Objects from the 16th to the 19th Centuries, Analysis of Materials and Pictorial Techniques. Heritage, 6(4), 3590-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6040191