Abstract

Gastronomy, as a part of cultural heritage, has exceptional potential in tourism, and its key representatives and conservationists/guardians are hospitality facilities that provide food services. Vojvodina (the Republic of Serbia) is a region inhabited by more than 30 ethnic minorities that have nurtured their cultural heritage and have been incorporating it into gastronomy for many years. The subject of this paper is the gastronomy of ethnic groups in Vojvodina and its significance for tourism development from the point of view of hospitality workers as important actors in the sustainability of heritage. One of the motives behind this study is the twelfth UN sustainable development goal (SDGs) defined in 2015, which refers to providing sustainable forms of consumption and production and which emphasizes the development and application of tools for monitoring the impact that sustainable development has on tourism that promotes local culture and products (12b). The aim of this study was to obtain data on the preservation of heritage, that is, on authenticity within the region/area and ethnic groups, and then to perform a valorization of dishes and define steps on how to make gastronomic heritage a more visible tourist attraction, from the perspective of sustainability. Our survey included a sample of 508 respondents, all employees in the hospitality industry. The obtained results were statistically processed. The research showed that the Južnabačka district has the greatest importance in tourism from the aspect of the implementation, preservation, and sustainability of gastronomic heritage in tourism. Among the ethnic groups, the Vojvodina Hungarians place the greatest importance on the preservation of gastronomy, which includes dishes such as goulash and uses ingredients such as river fish. The research led to the conclusion that those in the hospitality industry are of the opinion that gastronomic heritage should be promoted through activities such as tourist exposure, marketing activities, and promoting the diversity of authentic food offers in catering facilities.

Keywords:

sustainability; gastronomical heritage; cultural heritage; gastronomy; hospitality; tourism; Vojvodina; Serbia 1. Introduction

Gastronomic heritage (GH), as a part of cultural heritage, represents an important segment of tourism development, which has been the focus of numerous studies in recent years [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. This was demonstrated when its importance was recognized by UNESCO in 2010 as a part of intangible heritage, which should be nurtured and promoted in tourism [8,9].

Some elements of tourism gained special importance in 2015 when 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) were defined and adopted by all members of the UN. The twelfth goal refers to the provision of sustainable forms of consumption and production, with sub-goal 12b highlighting the development and implementation of tools for monitoring the impact of the sustainable development of sustainable tourism that not only creates jobs, but also promotes local culture and products [10]. Accordingly, Scheyvens and Laeis [11] point out certain possibilities in connecting food producers with the tourism industry, with the idea that both local food systems and the tourism industry could be improved by increasing the local food offered in hospitality facilities from the aspect of sustainable development.

GH serves as a means for attracting tourists and represents a territorial capital that brings great social, ecological, and economic benefits [12]. This has been confirmed by numerous studies, including that of Barientos-Báez et al. [13]. Dominguez et al. [14], in particular, point out the significance of tourism development from the aspect of local and regional development. Many tourism localities and hospitality facilities have recognized the importance of gastronomic potential for tourism development and have started to promote and offer their own authentic and traditional products [15,16]. In the search for authentic and traditional cultural experiences, gastronomy has become one of the primary motives for tourists to visit authentic ethnic restaurants [17], which, in turn, receive an additional value in tourism [18]. The conceptualization of authenticity from the perspectives of different authors was dealt with by Lu et al. [16]. They explained it from several perspectives, starting with the original and the staged and other forms and approaches. It is most important to emphasize that authenticity is widely conceptualized as a universal value and the driving force of the tourist movement.

Metro-Roland [19] states that certain foodstuffs, regardless of their true origin, become easily associated with certain gastronomic cultures and start to function metonymically. Thus, in some cuisines, they become dominant foods and representatives of the gastronomic culture.

The subject of this paper is the sustainability of GH in Vojvodina (the north of Serbia). This is a multicultural region inhabited by more than 30 ethnic groups, all of which affected the formation of the gastronomic identity of the region and its multifold significance for tourism development and sustainability throughout history. The GH created under the influence of various ethnic groups is, in its way, authentic and interesting for tourists [20,21]. Vojvodina is inhabited by numerous ethnic groups, who have managed to preserve the authenticity of the dishes and customs of their ancestors, despite various external influences [21]. A study conducted by Drakulić Kovačević et al. [22] in the South Banat region examined the determinants of the development of tourist destinations and found that gastronomy is a primary factor in determining the attractiveness of a region. Research among employees in the hospitality industry on the gastronomic heritage of ethnic groups from a particular locality has not been sufficiently researched around the world or in Vojvodina. This is the main reason we chose this topic.

The task of this paper is to present the preservation and evaluation of the GH of the region and the ethnic groups therein from the perspective of hospitality workers employed in hospitality facilities, who are representative subjects for this form of cultural heritage in tourism. Research conducted in hospitality facilities in the region showed that dishes offered by restaurants in Vojvodina are not authentic enough, that is, that the traditional dishes of certain ethnic groups are under-represented [21].

The aim of this paper is to use the data obtained during the course of this study to answer the following research questions:

- Q1: What region of Vojvodina, with its GH, conditioned by the structure of its population and authenticity, has the greatest potential for tourism development?

- Q2: Whose GH stands out from the aspect of demand, attractiveness, and potential in hospitality and tourism?

- Q3: What gastronomic specialties are most in demand and have the greatest significance in the hospitality offer?

- Q4: What would lead to the better recognition of GH based on the multiculturalism of the region, i.e., which elements and promotional activities in hospitality should be developed to make them sustainable in tourism?

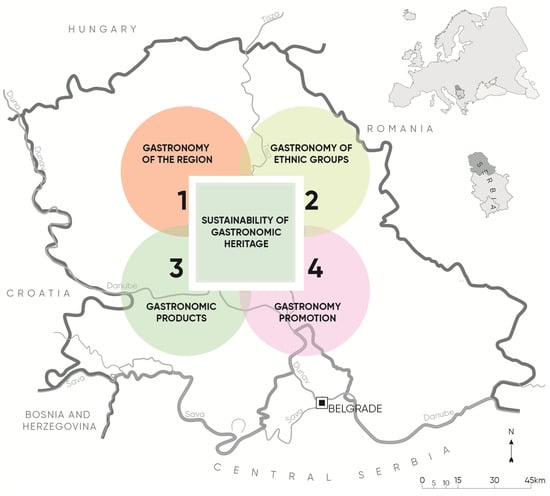

The answers to these questions will provide a clearer image of the state of preservation and valorization of GH, and additional guidelines for its better utilization in tourism. Thus, they will contribute to the preservation of gastronomy as a valuable form of intangible heritage. Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the elements studied that were important for obtaining insights into the state of GH sustainability and were included in the research questions. It is important to stress that the study included the six most numerous minority ethnic groups in Vojvodina.

Figure 1.

The studied elements of GH sustainability in Vojvodina. (Authors: Đerčan and Kalenjuk Pivarski, 2023).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gastronomic Heritage

GH has, to a considerable extent, started to attract the attention of European researchers, which is confirmed by the study conducted by Lin et al. [5]. Their study points to the increased significance of GH, along with activities for preserving cultural heritage [5]. Accordingly, Romagnoli [8] explains in his paper that GH includes a wide range of knowledge about food and culinary skills that communities consider to be common heritage and common social practices.

GH includes a large number of sociocultural components that affected its formation and differentiation and, therefore, it includes various kinds of agricultural and food products, different types of dishes, spices, food preparation methods, equipment, and appliances for food preparation, and modes of consumption, all of which can be found on the tourist market [23,24,25]. In this way, GH represents a marker of regional identity and highlights the complexity of this research field, which is receiving increasing attention [25,26].

GH represents the main factor in the differentiation of tourist destinations due to increased visitor interest in authentic food, which then becomes a primary motive for visiting a tourist area and region [25]. In this manner, based on the GH of local residents, tourists affect the formation of the destination image, whereby a symbolic relationship with local residents and gastronomy in tourism is created [27].

2.2. Hospitality Facilities as Places for Gastronomic Heritage Preservation and Nurturing in the Function of Tourism

Over the last 20 years, research on the impact of food-inspired tourism has shown significant progress in its development. All research focused on localities that offer unique, authentic gastronomic experiences, their marketing activities, and the sustainability of all the mentioned elements [28]. Okumus [28] points out gaps in the literature on certain topics, such as data on specific cuisines and cultures, impacts on the global food system, food waste, food safety, sustainability, workforce challenges, supply and demand, food authenticity, management, marketing, etc.

Research conducted in Vojvodina has so far focused on the food offered (domestic, national, international) in authentic catering facilities, which represent places for the preservation and nurturing of GH. In Vojvodina, in addition to ethnic and traditional restaurants, we should point out that there are also hospitality facilities:

- ‘Salashes’ (messuages): traditional dwelling houses with associated buildings and land, where people live permanently or temporarily, which are basically directed toward agricultural production [29,30,31]. Dishes offered in these hospitality facilities are authentic/traditional dishes prepared with local foodstuffs, and include pheasant soup, goose soup, hen soup, different kinds of roasts, breaded and stewed meat combined with salads and side dishes made with potatoes, tomato soup, beef soup, goulash, paprikas, cooked beans, stuffed peppers and cabbage rolls, and desserts such as yeast dough strudels with poppy seeds, walnuts and cherries, fruit pies with pulled dough, rolls with lard, noodles with poppy seeds, and the like [31];

- ‘Chardas’: hospitality facilities near rivers, which provide food and beverage services [32,33]. In Vojvodina, the chardas offer specialties made from river fish, and local foods such as fish broth, fish paprikas with dumplings or homemade noodles, smoked fish, fish pate, porkolt with pike and sterlet, drunken carp, and many other specialties [33] combined with red seasoning pepper.

Particular attention should be paid to the perspective and limitations of the development of tourism aimed at authentic food with a focus on of sustainable development [34]. They are the main factors that can improve or hinder this process of implementing and preserving gastronomic heritage through catering and tourism [11,35].

2.3. Gastronomic Heritage in Vojvodina (North Serbia)

Vojvodina is an agricultural region occupying an area of 21,614 km2 and 40% of it is arable land. Its population structure has changed throughout history as did habits related to preparing and enjoying food. In the past, gastronomy in Vojvodina was influenced to a considerable extent by Austrian, German, and Hungarian cuisine. In addition to these cultures and cuisines, the influence of Turkey was also significant, along with the impact of the migrations of Slovaks, Russians, Ukrainians, Rusyns, and other ethnic groups that brought their food preparation habits [21]. The area comprises three regions (Srem, Banat, Bačka) and seven administrative areas.

2.3.1. The Region of Srem

The hilly winegrowing and forested region of Srem (Syrmia) is located between the Sava and the Danube rivers. This region has very significant and varied gastronomic products that contribute to the authenticity of gastronomy in this district. Traditional regional products, created before the cultivation of autochthonous breeds of animals and plants, have significant potential for both gastronomy and tourism development. Among the valued traditional products is the dessert wine ‘Bermet’, but there are also many other kinds of wine and fruit brandies, linden honey from the Fruška Gora mountain, Syrmian kulen, Syrmian homemade sausage and Syrmian salami, plenty of meat specialties (mangalica products), dishes made with dough, and cakes [36].

2.3.2. The Region of Bačka

The region of Bačka is characterized by products that people living in this region have traditionally been producing for years [37]. Trends in tourism development increasingly involve the food industry as one of the crucial actors in the overall process. Bačka is an important region of Vojvodina because of its position, relief, and cultural heritage. It represents an environment rich in gastronomic specialties suitable for attracting tourists. A study conducted by Ivanović et al. [36] on the hospitality facilities in the South Bačka region showed that the most frequently used traditional products are various kinds of sausages, cheese, along with ajvar, bacon, and ham [36].

2.3.3. The Region of Banat

The Banat region, located, in part, on the border with Romania, is characterized by a rich cultural heritage manifested through different customs, multiculturalism, and rich gastronomy [38]. The Banat cuisine is characterized by delicious, fatty, and nutritious dishes. Various types of soups and stews with homemade pasta, pork, beef, and chicken dishes are consumed, while fish is slightly less common. Dishes are mostly fried and stewed in fat or oil, served with various flour sauces, seasoned with pepper, thyme, paprika, and caraway seeds [39].

2.4. The Gastronomy of Ethnic Groups in Vojvodina

Gastronomy in Vojvodina is characterized by a mix of dishes of almost all the ethnic groups that inhabit the area, among whom Hungarians, Slovakians, Romanians, Croatians, Montenegrins, the Roma, etc. prevail. Under their influence, the production and consumption of various dried meat products, smoked meat, and various kinds of sausages over time came to dominate the local diet. Many traditional vegetable and fruit dishes, various dough products, sweet dishes, and highly significant preserves, are also a part of that diet [26]. The similarity between dishes originating from various ethnic groups is frequent. Differences can usually only be found in the name, the preparation phase, an ingredient, or a spice [32].

2.4.1. Hungarian Gastronomy in Vojvodina

Hungarian cuisine is often described as very spicy and hot. In a study that incorporated tourists in Budapest, Hungarian gastronomy is recognized as a cuisine that uses a lot of paprika, and their most famous dish, which also symbolizes their cuisine, is goulash. This confirms the rich array of cultural and historical influences on gastronomy, especially since paprika travelled a long way through the Ottoman Empire [19]. The basic ingredients of the dishes of Vojvodina Hungarians are pork, veal, beef, and poultry. Pork fat and goose fat, and garlic, onion, curdled cream, mature cheese, walnuts, and poppy seeds are widely used. A combination of meat dishes with sweet flavors is very common [21]. A study conducted among the Hungarian population in Vojvodina shows traditional methods of food preparation are well preserved in their homes and the homes of their descendants [40].

2.4.2. Slovaks Gastronomy in Vojvodina

The cuisine of Vojvodina Slovaks is characterized by strong, hot, and very spicy dishes, with a lot of pork, various kinds of dishes made of dough, and sweets [6]. A study conducted among representatives of this ethnic group showed that they mostly independently produce certain kinds of food products, among which sausages (Slovakian kulen—a piquant sausage) hold a significant place. The greatest preservation of traditional dishes can be seen in the preparation of sweet dishes and pastry dishes [41].

2.4.3. Croatian Gastronomy in Vojvodina

Croatian cuisine is often described as a mix of neighboring cuisines with a large assimilation with Serbian cuisine. However, their dishes contain authentic segments that differentiate them from others, including different kinds of meat specialties, yeast dough dishes, pies, and cakes [21].

2.4.4. Romanian Gastronomy in Vojvodina

Romanian gastronomy is characterized by a simple cuisine, highlighting habits in preparing and consuming meat and vegetable soups, tripe or veal seasoned with lemon juice, sour cream, and vinegar. All these elements are also preserved in Vojvodina. Cornmeal porridge is eaten as a main dish or a side dish, or instead of bread. Pork and chicken are most commonly used, but beef, fish, bacon, ham, and various dried meat products are also present [6,41].

2.4.5. Montenegrin Gastronomy in Vojvodina

Montenegrin gastronomy is difficult to define because of the diversity of available foodstuffs in its region of origin. Like all other ethnic groups, the Montenegrin people tried to preserve as much of their gastronomic identity as possible. Integral parts of the cuisine in Vojvodina are dairy products, dried meat, and meat products. Various types of dough and porridge, different types of meat, lamb, and veal, and dishes based on sea and river fish are included [21,42].

2.4.6. Roma Gastronomy in Vojvodina

Roma cuisine is characterized by its simplicity. In Roma cuisine, dishes made of vegetables, combined with cooked or stewed meat, dominate. Paprika is the main spice, but pepper, salt, and garlic are also used. Roma cuisine is considered to be medium hot to very hot [6,41].

3. Methodology

3.1. Place of Research

This study was conducted in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, the region located in the north of the Republic of Serbia, which borders Croatia to the west, Hungary to the north, and Romania to the east. The capital of the province is Novi Sad, which is a tourist center in the South Bačka region, and is situated on the Danube river. The population of AP Vojvodina is 1,931,809 [43], of which 66.8% are Serbs. The rest is made up of ethnic minorities, of which there are more than 30. Among the most numerous ethnic minorities, we find Hungarians, who make up 13% of the population; the rest are Slovaks with 2.6%, Croats 2.4%, Roma 2.2%, Romanians 1.3%, Montenegrins 1.1%, and other peoples (Bunjevci, Rusyns, Albanians, Bulgarians, Goranci, Yugoslavs, Macedonians, Muslims, Germans, Russians, Slovenians, Ukrainians, Czechs, etc.), making up a total of 10.6% of the population [44,45].

3.2. The Questionnaire Structure

For the purposes of this study, a suitable questionnaire was created, which, in addition to obtaining sociodemographic characteristics, contained an additional four units focused on providing answers to the research questions. The research questions were formulated based on models from similar studies [6,21,40]. Some parts were adapted to the elements of the UN sustainable development goal (SDGs), which refers to providing sustainable forms of consumption and production while monitoring the impact of sustainable tourism development and local culture and products.

The questionnaire was first used to obtain data such as gender, age, education level, type of hospitality facility where the respondent works, work position, years of work experience in hospitality, and the region in which the hospitality facility is located.

Then, the first part of the questionnaire was focused on obtaining data from hospitality workers regarding their opinions on which region of Vojvodina has the greatest potential for tourism development based on GH. The respondents chose one of the seven given administrative areas.

The second part of the questionnaire was designed to obtain data on whose GH (of which ethnic group) is the object of demand in hospitality, whose gastronomy is considered attractive, and whose has potential for implementation in tourism. The most represented ethnic minorities included here are Hungarians, Slovaks, Croatians, Romanians, Montenegrins, and the Roma.

The third part was designed to obtain data on the most in demand dishes in hospitality, i.e., the most popular by area. In this part, the respondents gave specific examples of dishes.

The fourth part gathered opinions on what steps could be taken to improve the recognition and promotion of GH in tourism. It was an open-ended question with respect to all propositions that were later systematized and grouped.

3.3. Sampling

The questionnaire was distributed electronically using the database of email addresses of hospitality facilities in Vojvodina. All of the respondents were previously familiarized with the kind of research and informed about the anonymity of the questionnaire. The research was conducted between May and October 2022. Because the collection of the completed questionnaires was slow, the respondents were repeatedly asked to fill them in. The size of the sample was determined using the Raosoft sample size calculator. With the aim of obtaining relevant data, 700 questionnaires were sent out, of which 508 were completed properly and were statistically processed. The number of respondents in the Vojvodina regions was proportionate to the number of employees in hospitality according to the data of the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia [7,45]. Special attention was paid to the collection of data from respondents whose structure corresponds to the structure of employees in the hospitality industry according to official statistics, viewed according to gender, age, level of education, and the type of establishments in which they are employed. One person from management was interviewed in each facility. As such, the sample is considered representative.

3.4. Statistical Data Processing

To obtain responses to the research questions, the collected data were subjected to statistical processing procedures using software for social sciences SPSS v. 23.00. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, to describe the respondents’ answers regarding the region with the most preserved GH, the attractiveness of the dishes, the most desirable dishes of the ethnic groups, and to describe the responses of the respondents regarding their suggestions for better recognition and placement of GH in tourism.

3.5. Description of the Sample

As previously mentioned, data collection was carried out by surveying hospitality workers in Vojvodina. There were 508 respondents in total. The sociodemographic structure of the respondents is shown in Table 1. In addition to gender structure, age, and education level, the table shows relevant data on the type of hospitality facility where the respondents work, their position, and work experience in hospitality.

Table 1.

The sociodemographic structure of the respondents employed in hospitality and tourism facilities.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Regions with the Most Preserved Gastronomic Heritage Significant for Tourism

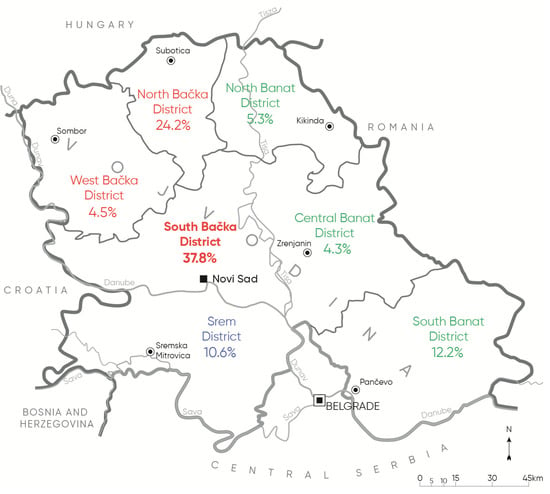

The first part of the study focused on investigating which regional areas hospitality workers considered to have the most potential for attracting tourists, as motivated by GH. Based on the results shown in Figure 2, the largest number of respondents named the South Bačka region with 37.8%, followed by the North Bačka region with 24.2%, the South Banat region with 12.2%, and the Syrmia region with 10.6%. Given that South Bačka is the administrative center of the region, with the highest population density and the most visited tourism center [46], these results are justifiable. This region is in a favorable tourist position as it contains numerous agricultural farms and has a rich gastronomic culture and tradition, which makes it a region with great potential for the development of the sustainable tourism concept based on local and traditional food [46].

Figure 2.

The area with the largest potential for attracting tourists motivated by gastronomical heritage (Author: Đerčan, 2023).

4.2. Analysis of the Attractiveness of the Dishes

The second part of the study focused on investigating the attractiveness, demand, and potential of the cuisines of the ethnic groups in Vojvodina. Table 2 shows the answers of the respondents. It is important to point out that questions concerning the potential of ethnic minority dishes were multiple choice questions (the respondents could choose several cuisines).

Table 2.

The current state of hospitality and the potential for tourism development from the point of view of the employees.

According to the respondents, the most attractive and the most requested dishes are Hungarian dishes with 76.8% and 80.3%, respectively, and they should be more represented in hospitality because the respondents believe that they have the greatest potential to appeal to tourists (70.3%). Some 38% of the respondents believed that Slovakian dishes also have potential, whereas the share of other ethnic minority cuisines was significantly smaller. A study conducted among the population of Vojvodina gave similar results [6].

4.3. The Analysis of the Most Requested Dishes of Ethnic Groups in Hospitality Facilities

The third part of the study focused on investigating which dishes from the ethnic minorities are the most requested in hospitality facilities in Vojvodina and which should be promoted. An open-ended question was posed, where the respondents were asked to name the dishes without a limited number of examples.

Due to the uneven distribution of the minorities in Vojvodina, the demand for these dishes was also analyzed by region; however, there were no major differences:

- In the South Bačka region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 80.95%, paprikas 20.63%, porkolt 19.5%;

- In the North Bačka region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 47.37%, paprikas 26.32%, porkolt 15.79%, fish soup 10.53%;

- In the West Bačka region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 66.67%, porkolt 33.33%, paprikas 25%;

- In the Central Banat region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 66.67%, porkolt 16.67%, fish soup 16.67%;

- In the North Banat region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 60%, porkolt 22%, and stuffed vegetables 17%;

- In the South Banat region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 80.95%, paprikas 20.63%, porkolt 19.5%;

- In the Syrmia region, the greatest demand is for the following dishes: goulash 68.75%, paprikas 9.38%, stuffed vegetables 6.25%, river fish dishes 6.25%.

Based on the results, it can be concluded that dishes from the Hungarian ethnic group are dominant, which coincides with the results from previous studies.

According to the hospitality workers, the most requested dishes from ethnic minorities in the hospitality facilities in Vojvodina include goulash 70.9%, paprikas 17.6%, and porkolt 14.2%, whereas other dishes have a smaller share and include fish soups, various kinds of meat dishes, stuffed vegetables (cabbage rolls, stuffed peppers, etc.), desserts, and dishes made with dough and eggs. These are dishes that are served in authentic local catering facilities, such as rural households converted into restaurant (messuages) and fish restaurants on the banks of the Danube and the Sava (chardas) [30,31,32,33].

4.4. The Analysis of Suggestions for Better Recognition and Placement of Gastronomic Heritage in Tourism

The last part of the study was focused on obtaining data that included suggestions for activities that would contribute to the better positioning of GH in tourism in Vojvodina. Only 15%s of respondents (i.e., N = 75) provided suggestions, and the results are grouped and shown in Table 3. The results show that for better recognition of the food and beverages of Vojvodina, with the aim of developing tourism directed at GH, most of the respondents suggested improving various types of tourist manifestations (37.3%), marketing activities (34.7%), diversity of offers in restaurants (22.7%), all of which are associated with an increased offer of authentic, traditional, and homemade dishes (20%).

Table 3.

Suggestions for better preservation of the gastronomic heritage of Vojvodina in tourism (N = 75).

Tourist manifestations aimed at promoting food and beverages were included in a significant share of suggestions made by the hospitality workers. They have an exceptional significance in the development of tourism and in attracting national and foreign tourists motivated by food in different ways [47,48]. The following suggestions stood out:

- Tasting, developing, and supporting gastronomic events by area; organizing socializing days, where ethnic groups will present themselves to others through food; the promotion of dishes of a certain nation with an explanation when they are eaten, why they are prepared with certain ingredients (related to the seasoning and foods that ripen at a certain time). There should be various offers during the whole year depending on current ingredients so as to promote naturally grown foods; organizing more exposure with the theme of national cuisines; frequent promotions of old-fashioned dishes; educating the population, organizing workshops, competitions, promotions; gastronomic exposure of national minorities; increasing the inclusion of various dishes in restaurants and hospitality facilities, providing more TV shows that promote this food, but in a way that is interesting and appealing to the young; more fairs, gastronomic competitions.

Marketing was included in many of the suggestions. The suggestions were mostly associated with the modern trends of internet technology, which are the basis for the initial interest of many tourists, and with smart technology and social networking lovers [13,26,49,50,51,52,53]. This included the following:

- Product branding; better placement of food through the media and social networks and blogs, where food authenticity is the most important element; a Facebook page with stories, photos, videos of the region, towns where national minorities represent the majority. This promotes their cuisine and the discussion about healthy food; greater placement in hospitality facilities and more TV shows that promote the cuisine of minorities, but in a way that is interesting and appealing to the young; informing, special shows; better information for tourists, but also for the local population.

A Diversity of offers was included in several suggestions, of which the following stand out:

- Introducing modern dishes alongside traditional ones which will contain ingredients from Vojvodina, that is, what is now popular in the human diet (more desserts with Plasma biscuits or more dishes, salads with sour cream); stimulating restaurants to offer food and beverages from Vojvodina; all hospitality facilities should have almost identical menus, with minimum differences, while national minority dishes should be combined with national specialties and represent a special offer that should be promoted; a larger number of restaurants with diverse offers of different national dishes.

Authentic, traditional, home-made dishes were also a part of the suggestions:

- Preserving the authenticity of dishes, which must be maintained, primarily through persistence and work on retaining their authenticity and place on the market; a return to the traditional cuisine and food preparation; pointing out the authenticity of our ancestors’ recipes; ethnic tourism, using messuages near towns, the price–quality ratio, a more modern aspect of sales of traditional cuisine, representation at ethnic festivals; indicating in the menu what food is authentic for the region.

Market research was the focus of the following suggestions:

- All dishes should be tasted (tasting and preparation); talking to the elderly about the dishes of their ancestors; visiting country households where food is prepared in an authentic way; looking for old recipes in villages.

Authentic domestic local ingredients were included in the following suggestions:

- Acquainting service users with the origin of the ingredients used to prepare dishes; offering only domestic products; stimulating households to produce ingredients or prepared products characteristic for a national minority; indicating in the menu which food is authentic for the region, and which ingredients.

Educating the population, employees, and managers was included in the following suggestions:

- Training of the staff and quality control; education, offer, detailed descriptions in the menus (nutritive values, characteristics of ingredients, advantages of processing methods, interesting facts); educating the population, some workshops, competitions, promotions.

In addition to these activities (grouped suggestions) for better recognition of GH in Vojvodina, interesting suggestions were included in over 10% of hospitality worker responses, but with a smaller percentage of frequency. They included the following:

- Organic and local products; diversity and well-balanced ingredients in dishes; co-financing ethnic restaurants as a motivator for offering traditional dishes; pairing traditional dishes with local wines; greater control of the food and beverage quality; better recognition of ethnic minorities by the government; standard product quality and awareness on the part of all the employees; defining exactly what are the dishes of Vojvodina; government incentives in presenting new products (without compensation).

This kind of data can be important for tourism management because it provides information on how to use the potential of gastronomic heritage in tourism and in relation to other localities [54].

5. Conclusions

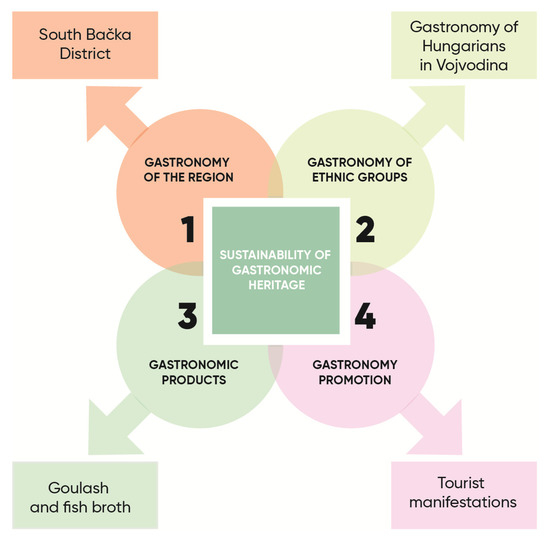

Taking into account the twelfth goal of the SDG, which refers to the provision of sustainable forms of consumption and production (ODS), and focusing on 12b, i.e., connecting sustainable tourism and local culture, the following conclusions were reached regarding GH in Vojvodina (as shown in Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Sustainability of the gastronomic heritage in Vojvodina (Authors: Đerčan and Kalenjuk Pivarski, 2023).

- Taking into account its GH as conditioned by the population structure and authenticity, we concluded that the South Bačka area of Vojvodina has the greatest potential for tourism development. It stretches along the Danube river and represents the most developed area of this region, which supports the obtained results;

- By analyzing the GH of the ethnic groups that inhabit Vojvodina, we concluded that from the aspect of demand, attractiveness, and potential in hospitality and tourism, the cuisine of Vojvodina Hungarians, who are the most numerous among the minority ethnic groups in the region and have a long history of living in these areas, stands out the most;

- By questioning hospitality workers about the most in demand dishes and the value of hospitality offers, we concluded that goulash and similar dishes are the most appealing. As a result of the local rivers and waterways, fish soup is also very popular. Both groups of dishes are seasoned with paprika, which is also a symbol of these cuisines;

- When examining the opinions of hospitality workers about what would promote the recognition of GH based on the multiculturalism of the region, that is, which elements in hospitality and tourism should be worked on, the largest percentage of respondents stated that tourist exposure, marketing promotions, and improvements in the diversity of the gastronomic offer would be the most effective. There were also many other proposals and suggestions.

5.1. Research Limitations

In terms of data collection, more detailed data could be obtained on the topic of gastronomic specificities and dishes, which are often interpreted differently among respondents, especially in the case of dishes of lesser-known ethnic groups in the region.

5.2. Practical Implications

Practical implications are given in the final study segment. For the better sustainability of GH in tourism, it is essential to implement all the elements obtained in the study and refer to the instructions that would best affect the better recognition of GH based on the multiculturalism of the region. Different activities as part of tourist exposure, marketing promotions, improving the diversity of the gastronomic offer in catering facilities, and many other, equally important activities, stand out here.

5.3. Suggestions for Future Research

For the better sustainability of GH in tourism, adequate qualitative research should be conducted among the population of the studied ethnic groups and hospitality workers, and concrete data should be obtained on food preparation in a traditional and authentic way. Attempts should be made to include these data as much as possible in the hospitality and tourism regional offer.

In addition, future directions of research should include an overview of the problem of managing visitors’ gastronomy satisfaction in the region, as this is an extremely important component of the successful development of tourism, as shown in research conducted on a global level [54].

Author Contributions

B.K.P. and B.G. conceptualized the research; B.K.P. led the research team; B.K.P., B.G. and B.Ð. set the methodology; B.K.P., B.G., M.B. and D.T. were in charge of collecting data for literature review; B.Ð., V.V. and S.Š. were in charge of arranging the work; G.R., V.I., S.Š., V.V. and T.S. participated in the collection of data from the field and preparation for statistical processing; B.G. and M.B. carried out statistical analyses. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research, project name: Sustainability of the gastronomic heritage in the hospitality of Vojvodina and its importance in developing tourism in the region, Grant No. 142-451-2299/2022-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

An Institutional Review Board Statement is not required for this paper in Serbia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request due to restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants of this research for their effort and time. The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of R. Serbia (Grant No. 451-03-47/2023-01/200125) and the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research (No. 142-451-2299/2022-01) for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Avieli, N. What is ‘local food?’ Dynamic culinary heritage in the World Heritage Site of Hoi An, Vietnam. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivza, B.; Kruzmetra, M.; Foris, D.; Jeroscenkova, L. Gastronomic heritage: Demand and supply. Econ. Sci. Rural Dev. Conf. Proc. 2017, 44, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Huete-Alcocer, N.; Hernández-Rojas, R.D. Does local cuisine influence the image of a World Heritage destination and subsequent loyalty to that destination? Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruzmetra, M.; Rivza, B.; Foris, D. Modernization of the demand and supply sides for gastronomic cultural heritage. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2018, 40, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.P.; Marine-Roig, E.; Llonch-Molina, N. Gastronomy as a sign of the identity and cultural heritage of tourist destinations: A bibliometric analysis 2001–2020. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubor, B.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Đerčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M.; Lukić, T.; Živković, M.B.; Udovičić, D.I.; Šmugović, S.; Ivanović, V.; et al. Traditional and Authentic Food of Ethnic Groups of Vojvodina (Northern Serbia)—Preservation and Potential for Tourism Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Šmugović, S.; Tekić, D.; Ivanović, V.; Novaković, A.; Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M.; Đerčan, B.; Peulić, T.; Mutavdžić, B.; et al. Characteristics of Traditional Food Products as a Segment of Sustainable Consumption in Vojvodina’s Hospitality Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, M. Gastronomic heritage elements at UNESCO: Problems, reflections on and interpretations of a new heritage category. J. Intang. Herit. 2019, 14, 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Muangasame, K.; Kim, S. ‘We and our stories’: Constructing food experiences in a UNESCO gastronomy city. Tour. Geogr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How the UN supports the Sustainable Development Goals in Serbia. Available online: https://serbia.un.org/sr/sdgs (accessed on 30 December 2022). (In Serbian).

- Scheyvens, R.; Laeis, G. Linkages between tourist resorts, local food production and the sustainable development goals. In Recentering Tourism Geographies in the ‘Asian Century’; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Barska, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. Traditional and regional food as seen by consumers–research results: The case of Poland. Br. Food, J. 2018, 120, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Báez, A.; Caldevilla-Domínguez, D.; Vizcaíno, A.C.; Val, E.G.S. Sector Turístico: Comunicación e Innovación Sostenible. Rev. Comun. SEECI 2020, 53, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, D.C.; García, E.G.; Báez, A.B. La importancia del turismo cultural como medio de dignificación del turista y de la industria. Mediac. Soc. 2019, 18, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almli, V.L.; Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Næs, T.; Hersleth, M. General image and attribute perceptions of traditional food in six European countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Lu, C.Y. Authenticity perceptions, brand equity and brand choice intention: The case of ethnic restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rojas, R.D.; Huete Alcocer, N. The role of traditional restaurants in tourist destination loyalty. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, B.; Carroll, G.R.; Lehman, D.W. Authenticity and consumer value ratings: Empirical tests from the restaurant domain. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metro-Roland, M.M. Goulash Nationalism: The Culinary Identity of a Nation. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 172–181. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1743873X.2013.767814 (accessed on 7 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ðerčan, B. Ethnicities of Vojvodina at the beginning of the 21st century. In Ethnic Groups of Vojvodina in the 21st Century—State and Perspectives of Sustainability; Lukić, T., Bubalo-Živković, M., Blešić, I., Klempić-Bogadi, S., Župarić-Iljić, D., Podgorelec, S., Ðerčan, B., Kalenjuk, B., Solarević, M., Božić, S., Eds.; Faculty of Sciences: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2017; pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kalenjuk, B. Food and nutrition of the population of Vojvodina in the function of tourism development, as a reflection of the offer of catering facilities. In Ethnic Groups of Vojvodina in the 21st Century—State and Perspectives of Sustainability; Lukić, T., Bubalo-Živković, M., Blešić, I., Klempić-Bogadi, S., Župarić-Iljić, D., Podgorelec, S., Ðerčan, B., Kalenjuk, B., Solarević, M., Božić, S., Eds.; Faculty of Sciences: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2017; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Drakulić Kovačević, N.; Kovačević, L.; Stankov, U.; Dragićević, V.; Miletić, A. Applying destination competitiveness model to strategic tourism development of small destinations: The case of South Banat district. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J.; Tibère, L. Innovation in food heritage in the department of the Midi-Pyrenees: Types of innovation and links with territory. Anthropol. Food 2010, 11, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Genc, R. Gastronomic heritage in tourism management. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Priego, M.A.; García, G.M.; de los Baños, M.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Caridad y López del Río, L. Segmentation based on the gastronomic motivations of tourists: The case of the Costa Del Sol (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J. ‘Heritagisation’, a challenge for tourism promotion and regional development: An example of food heritage. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J.; Tibere, L. Traditional food and tourism: French tourist experience and food heritage in rural spaces. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3420–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B. Food tourism research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović, D. Salaši Vojvodine kao čuvari tradicije—Primer jednog salaša. Agroekonomika 2012, 55, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Božin, M. Salaši for You; Prometej: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Kalenjuk, B.; Cvetković, B.; Blanuša, J.; Lukić, T. Authentic food of Hungarians in Vojvodina (North Serbia) and its significance for the development of food tourism. World Sci. News 2018, 106, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Božin, M. Čarde na Dunavu; Daniel Print: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2006. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Banjac, M.; Kalenjuk, B.; Radivojević, G.; Babić, M. Structure of Gastronomy Offer in Charda Restaurants in Vojvodina Region as a Authentic Catering Facilities. In Proceedings of the The Sixth International Biennial Congress Hotelplan 2016, Belgrade, Serbia, 4–5 November 2016; pp. 535–543. [Google Scholar]

- Bertella, G.; Vidmar, B. Learning to face global food challenges through tourism experiences. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.-C.; Liu, J.; Lin, H. Affective components of gastronomy tourism: Measurement scale development and validation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, V.; Kalenjuk-Pivarski, B.; Šmugović, S. Traditional gastronomy products: Usage and significance in tourism and hospitality of southern Bačka (AP Vojvodina). Zb. Rad. Departmana Za Geogr. Turiz. I Hotel. 2022, 51/1, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, T.; Kalenjuk, B.; Đerčan, B.; Bubalo-Živković, M.; Solarević, M. Traditional Food Producers and Possibilities of Their Tourist Affirmations the Territory of Bačka (Serbia). Eur. Geogr. Stud. 2017, 4, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bjeljac, Ž.; Terzić, A.; Lukić, T. Tourist events in Serbian part of Banat. Forum Geogr. 2014, 13, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordean, D.M.; Petroman, I.; Petroman, C.; Claudia, S. Study on Banat’s Traditional Gastronomy. Agronomie 2009, 52. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228670837_STUDY_ON_BANAT%27S_TRADITIONAL_GASTRONOMY (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Kalenjuk, B.; Cvetković, B.; Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M. Gastronomic tourism in rural areas of Vojvodina (North Serbia)—Dispersion, condition and offer of authentic restaurants “messuages”. World Sci. News 2018, 100, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- TOV—Tour Organization Vojvodina. Ethno Colors of Vojvodina—Ethnic Wealth of Vojvodina; TOV: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lukić, T.; Jovanović, G.; Bubalo Živković, M.; Lalić, M.; Đerčan, B. Montenegrins in Vojvodina Province, Serbia. Hum. Geogr.–J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 8, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, T.; Bubalo-Živković, M.; Đerčan, B.; Solarević, M.; Kalenjuk, B. Ethnic groups of the Vojvodina Region (Serbia): Contribution to knowledge about the characteristics of cohabitation. Anthropologist 2017, 30, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubalo-Živković, M.; Đerčan, B.; Lukić, T. Changes in the number of Slovaks in Vojvodina in the last half century and the impact on the sustainability of Slovakia’s architectural heritage. Zb. Rad. Departmana Geogr. Turiz. Hotel. 2019, 48, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Population by Ethnicity Census 2011; Additional Data Processing; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Banjac, M.; Tešanović, D.; Dević Blanuša, J. Importance of connection between agricultural holding and catering facilities in development of tourism in Vojvodina. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Academic Conference “Science and Practice of Business Studies”, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 15 September 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 994–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Goh, B.K.; Yuan, J. Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring food tourist motivations. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 11, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Robinson, R.N. Foodies and food events. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 14, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sala, A.M.; Campillo-Alhama, C.; Ramos-Soler, I. Gen Y: Emotions and Functions of Smartphone Use for Tourist Purposes. In Tourism; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sala, A.M.; Monserrat-Gauchi, J.; Segarra-Saavedra, J. The influencer tourist 2.0: From anonymous tourist to opinion leader. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 1344–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sala, A.M.; Monserrat-Gauchi, J.; Alemany-Martínez, D. User Usable Experience: A three-dimensional approach on usability in tourism websites and a model for its evaluation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Báez, A.; Domínguez, D.C.; Mateus, A.F. Inmersión en la digitalización de las redes sociales en turismo y el patrimonio: Un cambio de paradigma. Anu. Electrónico Estud. Comun. Soc. "Disert." 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Báez, A.; Caldevilla Domínguez, D.; Cáceres Vizcaíno, A.; Sueia Val, E.G. Tourism Sector: Communication and Sustainable Innovation. Rev. Comun. SEECI 2022, 53, 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rojas, R.D.; Huete-Alcocer, N.; Hidalgo-Fernández, A. Analysis of the impact of traditional gastronomy on loyalty to a world heritage destination. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).