1. The Reconstruction of Working-Class Neighborhoods in Berlin before 1976

After World War II (1939–1945), the central area of Berlin was particularly damaged, while 5% to 15% of its periphery was affected [

1] (p. 135) (

Figure 1a). In this period, Berlin was offered the rare and unique opportunity to obliterate the construction of the city of the

Mietskasernen (tenement houses) and build a new urban structure.

The main part to be reconstructed was the 19th-century Hobrecht enlargement, built during the era of the German Empire. The Hobrecht Plan (1852–1862) (

Figure 1b) allowed the pre-industrial city to grow by 4,000,000 inhabitants and was extremely densified from 1871 until the First World War (1914–1918). It was structured by a radial grid of large blocks that were 200 to 400 m long and 150 to 200 m deep (

Figure 2a), with 22 m high buildings separated by at least 5.30 m × 5.30 m courtyards (

Figure 2b). The Hobrecht Plan was stimulated on the one hand by the growth of the mechanical, electrical and chemical industries, and on the other hand by oversized tax benefits for the owners of the land [

2].

The number of inhabitants grew exponentially from 932,000 in 1871 to 3.7 million in 1910 [

3], and the city was mainly developed by private investors, especially by large companies, as in other large European cities of the 19th century. This development led to great land speculation and rental prices so high that citizens were overcrowded, much more than in other industrialized cities. Berlin’s population density was, for example, ten times higher than London’s or double that of Vienna’s during the same period [

2].

During the period immediately after the war, attempts were made to propose and implement different ways of reconstructing Berlin. While the post-war plans were being developed, the reconstruction began with the social organization of the

Trümmerfrauen (Women of the Rubble); this hard work was led mainly by female neighbors who classified, cleaned and organized the different materials and constructive elements from the debris of the houses and facilities damaged or destroyed during the war. This action immediately improved the living conditions of the inhabitants during the years after the war. However, despite this civic effort, the majority of the post-war reconstruction efforts were organized by the

Schreibtichpläner [

1] (p. 165) projects (office planner designs) for the new Berlin, and international competitions to decide the future of the city were held to open the debate beyond the German borders.

1.1. The Housing Conditions in Border Neighbourhoods

A second period began after the erection of the Wall on 13 August 1961. The idea that the reconstruction of the city under modern parameters was at war with the inhabitants became hegemonized. The Berlin Wall, together with the 1973 oil crisis, caused the price of land near this border to plummet.

Since pre-war Berlin, the center and the most traditional neighborhoods had remained on the eastern side (

Figure 3). West Berlin was thus walled in and had no other connection to the past than through part of the Hobrecht enlargement. Its social structure was as peculiar as its population pyramid: the very young (mainly students and the unemployed) and the old predominated, while those between the ages of 30 and 60 were scarce [

5].

The steady decline in population, regarding which specialists even discussed the minimum figure below which the city’s viability would no longer be assured, was a clear sign of West Berlin’s difficult situation [

6]. The city had lost all the advantages that in the past had given rise to its strength: from being the capital, it ceased to be the political, administrative and financial center of Germany; from a strategic communications perspective, it became a remote, walled-in place that was difficult to access; from an industrial center with an organized working class, it was rapidly deindustrialized and turned into the service sector. Economically, the city was neither autonomous nor viable [

5].

In 1962, Werner March’s reorganization plan for West Berlin was approved (

Figure 4a). It was inspired by the Collective Plan of 1948, which proposed major road infrastructures crossing the existing urban fabric of the old city (

Figure 4b). An urban structure that, after the 1973 crisis, the government would group by large plots of land in order to make them more attractive to private investment [

5]. This plan was called the

Sanierung Plan (Sanitation Plan) and was approved by the

Senatsverwaltung und Sanierungsträger (Berlin Senate and Sanitation Committee).

As a result, the so-called Superblocks [

8] (

Figure 4c) were planned to be built in the center of the city, while mass housing developments with densities approximately ten times higher than in the outskirt garden cities of the 1920s were intended for the periphery. For example, if we compare “Märkisches Viertel” (1963–1974) by Hans C. Müller, Georg Heinrichs und Werner Düttmann with the famous “Siemmenstadt” (1929–1931) by Hans Scharoun, we will perceive that the profit of land increased with the new developments.

The price of housing offered in these new housing blocks was higher than the rents of the Mietskasernen that were still standing. This type of operation added to the loss of consumer power in the middle and working classes after the oil crisis, and opened a strong wave of criticism against this model of reconstruction, which triggered numerous citizen protests. A strong social organization finally managed to partially stop such plans, especially in working-class areas in the surroundings of the wall.

According to the social movements, Werner March’s Sanitation Plan attempted to reduce the housing issue by subjecting architecture to the economy and profitability of land. Numerous photographs of protests in these neighborhoods (

Figure 5a), newspaper covers (

Figure 5b), and posters (

Figure 5c), were collected in this research, demonstrating the strong tension characteristic of this period. The people that were living in the existing

Mietskasernen were only guaranteed a basic subsidy as a source of income; this was named the

Berlin Aid Policy [

5]

, and was approved by the West German government in order to ensure the repopulation of the city. The demolition of the old tenement houses for new housing increased the price of rent, which, together with the complete renovation of the urban structure, disrupted the existing social life and community [

1]. In this sense and as an example, the protests against the superblock NKZ (

Neues Kreuzberg Zentrum) in 1963 in the heart of Kreuzberg, a neighborhood divided by the wall, became very famous.

1.2. Debates about the Cultural Heritage role in West Berlin around 1976

A very important event for the reconstruction of West Berlin was the celebration of the

European Year of Architectural Heritage in 1975 in Amsterdam (

Figure 6), proclaimed by the European Council [

9]. The historic city was rediscovered, and among the constructions or aspects to be preserved were not only the monuments and churches, but also the existing houses and the city’s urban structure [

10]:

“Heritage comprises not only isolated buildings of outstanding value and their setting, but also ensembles, city districts and towns of historical or cultural interest. [...] The rehabilitation of old quarters should be conceived and carried out, as far as possible, in such a way that the social composition of the residents is not substantially modified and that all strata of society benefit from an operation financed by public funds.”

Under pressure from social movements, the meeting

Eine Zukunf für unsere Vergangenheit (A Future for our Past) was held in Berlin in the autumn of 1976 (

Figure 6). It was connected with the agreements of the

European Year of Architectural Heritage and it was held to discuss the specific problem of West Berlin.

The Council of Europe General Secretary said the following of the city [

11]:

“Berlin is both a reason and a cause of social ills while at the same time it is the bearer of qualities that we are beginning to discover today. Its neighbors want to preserve it because it is their home; sociologists consider the feeling of attachment to a place to be important; some urban planners think it can be an urban model of tomorrow; economists think the proposition is viable; tourists find great diversity in these neighborhoods. Therefore, politicians must work to find mechanisms for the preservation of the architectural heritage.”

In 1976, citizen protests reached their peak against the Sanitation Plans, which were mostly concentrated in neighborhoods near the wall. The broad support for the people’s fight finally led to the abandonment of these plans for a few years and to the research of new solutions [

1].

The European Year of Architectural Heritage and the Amsterdam Charter were of great significance in Berlin, especially for social movements protesting against Sanitation plans. It remained to be seen in what ways another materialization of the city was possible.

Architectural debates were promoted by the Senator of Architecture Hans C. Müller at the same time as the specific debates surrounding heritage at

A future for our past. The most important and representative debates in architecture were as follows [

3]: (1) The

Pilot Project Block 118 in Charlottenburg and (2) the

Symposium Stadtstruktur Stadtgestalt (Symposium on urban structure and urban form). The first one was promoted by the social movements and was technically supported by the architect Hardt Waltherr Hämmer, together with Julius Posener and Thomas Sieverts, who were all professors at the HfbK (now UdK); the second one was organized as an international event to import new formal methodologies to work with those already existing.

2. The Pilot Project for the Block 118 and the Symposium Stadtstruktur Stadtgestalt, Charlottenburg (1976)

2.1. The Pilot Project Block 118 in Charlottenburg

The Block 118 prototype was a bottom-up proposal, formulated by neighborhood associations and that included the renovation of an entire block with the typical structure of

Mietskasernen in Berlin-Charlottenburg (

Figure 7).

The main architect in this project was Professor Hardt Waltherr Hämer, together with his research group at the HfbK, who was able to carry it out in alliance with tenants and neighborhood associations despite the fact that the sanitation plans were already approved [

12]. The renovation of this Block was the formal basis on which to establish 12 principles for the so-called Cautious Urban Renewal (

Table 1), in order to reconstruct and conserve the built environment.

The methodology tested in the project’s context was interesting and innovative in because it proposed the phases for the reparation (

Figure 8a), the prioritization of damages (

Figure 8b) and the relocation of tenants (

Figure 8c), in order to provide an affordable proposal for the tenants (

Figure 8).

The Block 118 was delimited by the streets Schlossstrasse, Neue Christstrasse, Nehringstrasse and Seelingstrasse. At the beginning of the renovation, it had 675 residential units and 40 partly vacant commercial units, with a total of approximately 62,500 sqm of floor space in mostly five-story buildings constructed between 1886 and 1909, some of which were damaged during the war.

The Sanitation Plan, although already approved, was stopped, thus making it possible to involve the tenants, who could remain in their apartments and only had to leave them for a short construction period. The building renovation was now seen as an opportunity to make better use of existing resources and to reduce costs (

Table 2).

Despite the social organization, in 1976, a total of 18,000 houses were demolished, compared to 400 that were rehabilitated [

13]. The group of architects and residents represented by Profesor Hämer’s arguments focused on preserving the social structures that inhabited the historic districts, the small stores, and the quality and diversity of public space. Furthermore, they demonstrated that it could be more economical to preserve than to demolish and build anew (

Table 1).

The underlying idea was to transform the role of the architect to a figure capable of promoting the active participation of citizens and a collective decision-making process, introducing a more pragmatic vision in which the user took the leading role.

One of the main requirements was the preservation of the social structure (70% of the residents were to remain living there), the block structure and its mixed used. The two main objectives were to revitalize the old quarters and, as far as possible, to implement the wishes of the tenants; their participation was a fundamental condition for the planning and implementation because it was conceived as the essential prerequisite for achieving the cost advantage over new construction.

Another interesting and innovative methodological approach, very important for the further reconstruction of the city, was the differentiation of two main categories in the construction work: specialized and non-specialized (easy) works. This method allowed those involved to list the tasks that could be completed by the users themselves. In this context, civic participation was both understood as the capability to take part in the decision-making process for the desired mixed uses, and also in the construction and reparation of non-dangerous parts.

Three months after the start of the construction work, most of the residents in the first construction phase were able to move back into their apartments. Some of them remained in the house during the entire reconstruction period. From August 1976 to March 1977, 70 housing units were modernized. From August 1977 to August 1978, 120 residential units were refurbished. During 1978, 120 units were modernized, and in the following two years, approximately 80 units were completed. Approximately 50 residential units in the rear buildings were used for the interim relocation of tenants.

One of the most important ideas to which the group committed itself regarding the residents was that they would be able to participate in all the debates and decision-making processes that would be convened to facilitate urban renewal. After the successful experience of the Pilot Project Block 118, the group developed a program of cautious urban renewal, which was born out of the neighborhood movements; this project did not only demand to be consulted in decision-making processes, but had already organized to rebuild the houses on its own.

The theory of Cautious Urban Renewal for West Berlin presented 12 principles as a manifesto, in order to stablish agreements for the collaboration between investing companies, representatives of local interests, construction professionals in general and inhabitants in the affected areas. These 12 principles are summarized in

Table 1.

This program adhered to the idea that reconstruction under post-war modern city planning was too conditioned by the needs of investment capital. This relationship, according to Hämer, had led to the expulsion of the neighborhood’s inhabitants to more peripheral areas [

12].

“In cities, it’s all about negotiations and exchange. More and more companies are only interested in profits. They come to the cities like pests and destroy the culture and the daily life of the people. Don’t get me wrong: profit is not a bad thing, it’s the quick profits that I don’t like. Quick profits are fatal to urban culture.”

The previous Sanitation Plans meant that the working population was losing its roots, which it had suffered since the end of World War II. In response to this, the proposal considered it essential to contemplate the existing inhabited urban structures’ cultural heritage to give voice to the needs of residents and to recover a more pragmatic vision.

2.2. Symposium Stadstruktur Stadtgestalt

In October 1976, the above-mentioned Senator of Architecture Hans C. Müller organized a second event to discuss internationally alternative methodologies to formalize the urban reconstruction. The encounter was celebrated and sponsored by the Internationales Design Zentrum in West Berlin. This meeting took place over a week in the form of an intense drawn-debate with five renowned international architects: Gottfried Böhm (Cologne), Vittorio Gregotti (Milan), Peter Smithson (London), Alvaro Siza (Porto) and Oswalt Mathias Ungers (Cologne). A few weeks earlier, these architects had met at the Venice Biennale debate Europe/Americas: Urban Architecture, Suburban Alternatives, led by Vittorio Gregotti.

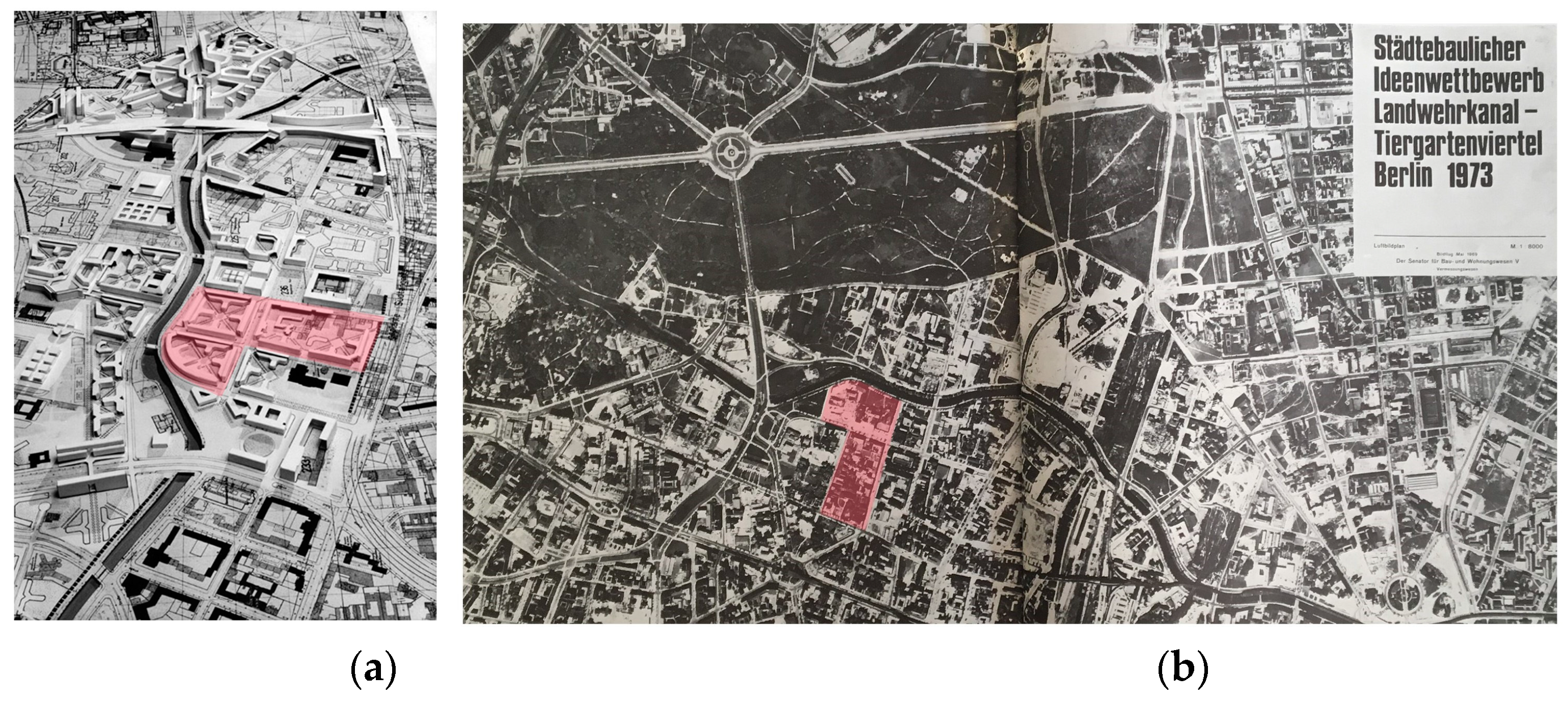

The organization of the Symposium was intended to overturn the arrangements made in a major international competition (

Figure 9a) that was held by the Berlin city administration in 1973 for the entire Tiergarten Süd (

Figure 9b), on both sides of the Landwehrkanal [

14] (

Figure 9). This competition shows how that architectural period was characterized by large-scale proposals that obliterated past construction (keeping only a few listed monuments from the past) and formalized designs with no relation to the existing city.

The large number of gaps in the old 19th-century urban fabric produced by the bombings of World War II, the area’s proximity to the wall and the need for an alternative to the post-war reconstruction plan formulated for the competition in 1973, became the perfect setting for the international debate, in order to draw an architectural critique of the post-war modernity [

16].

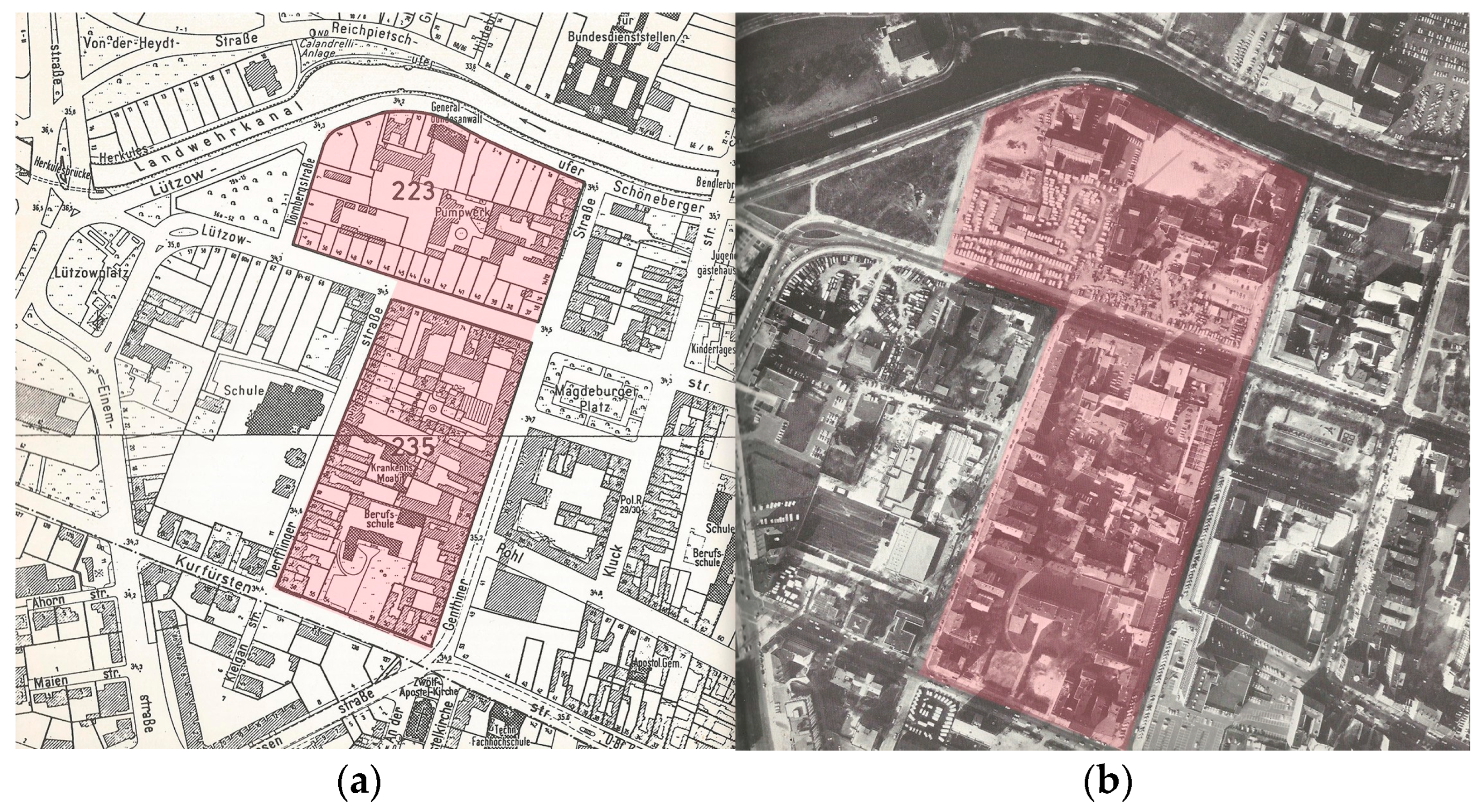

The organizers of the Symposium called for a first outline of the urban architecture that was being discussed on the international scene (

Figure 10a,b). During that week, the architects were asked to focus their proposals primarily on two issues: on the one hand, to organize public and private uses, while establishing connections within blocks 235 and 223 (

Figure 10a,b); on the other hand, to recover the 18th-century block urban structure, with housing and mixed programming on the ground floor.

As can be read in the proceedings compiled by François Burkhardt [

17], the symposium’s approach considered the existing urban fabric as cultural heritage, and looked for solutions to make life possible in historical buildings and existing structures. This could be attained both through the rehabilitation of housing and through new construction, when needed. They considered that the city block should be recovered as a structural unit of the city [

17] and that its use should be mixed. This requirement would not only have functional or programmatic consequences, but also spatial ones, since the possibilities of this model were unknown and would be debated on the basis of the invited architects’ proposals.

For the organizers, three types of space were at stake through the recovery of the block: the street as a public space and structural axis; the houses grouped around the block’s perimeter; and the private or semi-private inner courtyards of the block. In this sense, the block became a fixed element with the street as the main relational element. This strategy, despite being the most hegemonized among the Berlin proposals in the following years, denied and expropriated the free and genuine use of the inner courtyards’ space that had been left exposed after the war. This aspect is discussed in Siza’s and Smithson’s proposals.

Blocks 223 and 235 were located between Genthiner Street, Derfflinger Street, Kürfursten Street and the Landwehrkanal, an area with old buildings waiting for rehabilitation and with large storage and parking areas. Within the blocks, there was a former 19th-century water pumping station, a hospital and a trade school already protected as cultural heritage sites. Block 235 remained more built up than Block 223, and included the trade school and the Moabit Hospital. Despite these urban attractions, the area surrounding them was described as chaotic during the 1973 competition due to their arbitrary use and the insufficient spatial entity of the streets. In general, there was a lack of urban unity, which was one of the aspects that motivated the choice of the site for this meeting.

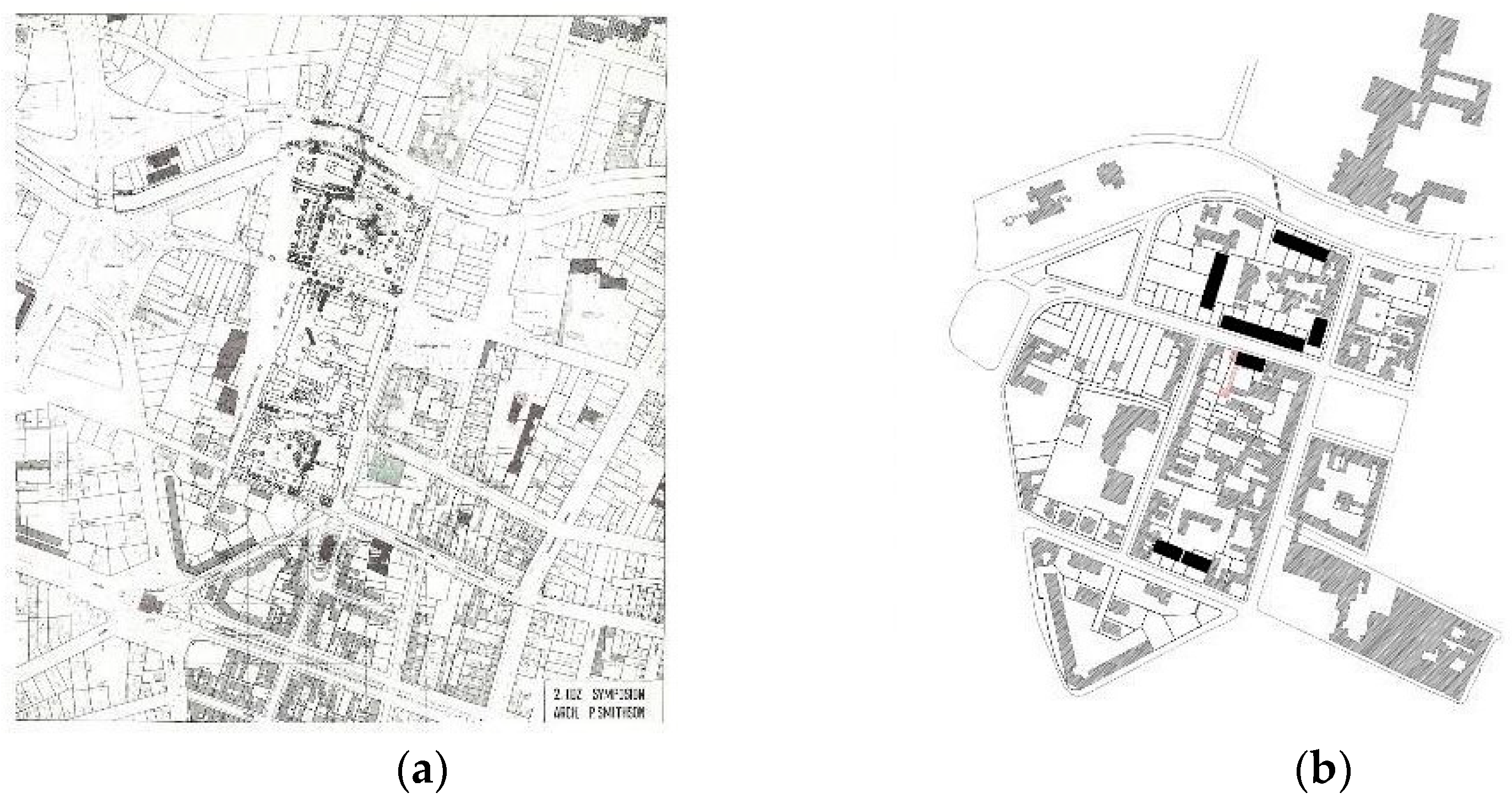

On the one hand, Göttfried Böhm (

Figure 11a,b), Vittorio Gregotti (

Figure 12a,b) and Oswalt Matthias Ungers (

Figure 13a,b) focused their proposal on the block model that was best adapted to the site and best embodied the positive values of the idea of urban program mixture. Álvaro Siza (

Figure 14a,b) and Peter Smithson (

Figure 15a,b), on the other hand, did not start with the idea that the block model was a structural element of the city, but with the idea of restructuring the existing site through the insertion of housing units analogous to their surroundings. Here, there were different strategies: the first three discussed the most ideal model for the city, and the other two discussed how to work with the existing.

In this second event of 1976, unlike the Pilot Project Block 118, no cost table was presented for the guarantee of its viability, nor was it able to demonstrate that it would succeed in maintaining the existing social structures. However, this event was important as it demonstrated the changes in attitudes and ways to develop new methodologies that offered the formal ability to work from the existing structure and formalize the city from it.

This was a change in attitude and a period strongly influenced by Aldo Rossi’s

Architecture of the City, in which the historical formal basis of the collectively inhabited spaces of the city was established [

18]; this was a theory for an urban development form that was outside the criteria of economic efficiency and profitability.

3. The Reconstruction after 1976 and before the Constitution of the IBA 84–87

Disparate groups of inhabitants continued waging a hard fight during the late seventies against the administration for working under the urban sanitation plan’s policies. The social movements succeeded in showing that the urban development that was being approved was incompatible with the existing community life. The neighbors and the municipal administration agreed in 1978 to run the ZIP [

19] (

Zukunftsinvestionsprogramms, Future Investment Program) supported by Harry Ristock, German Senator for Architecture and Housing, and by Hans C. Müller (

Figure 16a,b,c). The program was designed to seek a consensus between investors and residents.

The Frankelufer area, a huge four-block complex in Luisenstadt [

5], had been sold to an investment firm called GSW (

Figure 4b). Thanks to this first ZIP program, it was agreed with the Senate that investors should reach agreements with tenants on their renovation plans. These negotiations began to moderate the urban development and several citizen initiatives started the rehabilitation of the existing housing stock, partially relying on the technical capacity of the neighborhood’s residents to self-construct the area. In Luisenstadt, a collective of architecture students from the Technische Universität Berlin, called StuK [

20], began to organize and advise self-construction workshops for the rehabilitation of occupied houses [

21] (

Figure 17a). On the opposite side of Kreuzberg, in Sector SO36, there was also the initiative

Ideen für Kreuzberg (Ideas for Kreuzberg) for the self-build rehabilitation of tenants’ houses, promoted by Pastor Klaus Duntze and the evangelical community of St. Thomas (

Figure 17b).

At the same time that this work was being carried out, the Internationalle Bauausstellung (International building exhibition), IBA, was founded in December 1978; this was a commission of experts for the reconstruction of the west-east strip that ran along a large part of the wall and at the southern part of the Tiergarten.

The Foundation of the IBA and the Division into de Old and the New

The Internationalle Bauausstellung—IBA’84 was created at the end of 1978 as a publicly funded agency following a proposal by Hans C. Müller, together with the support of the Abgeordnetenhauses (House of Representatives). It was consolidated in 1981 as IBA’84–87. It emerged under the slogan Die Innenstadt als Wohnort (The inner city, as a place to live) and represented a vigorous initiative aimed at rebuilding and repairing a large amount of central urban space, especially the areas of study that were looking for a new plan to replace the previous plan of Werner March.

The New IBA took place in the part closest to the new center of West Berlin: Zoo, Charlottenburg and Tiergarten; and the Old IBA was confined to the most peripheral and distant areas of the new center, bordering the wall (

Figure 18). The IBA achieved worldwide recognition thanks to the international press and had a considerable impact on the city due to the large public investment made: GM 3 billion was invested in housing (3000 new and 5500 renovated) and facilities, including kindergartens, schools, homes for the elderly, youth centers, libraries, etc. [

22].

The postmodern criticism against modernist urban sanitation plans were crystallized worldwide with the IBA, and the idea that it was necessary to recover the urban structure of the 19th century city, which had been undertaken by reformist socialists, such as Werner Hegemann, was hegemonizing.

The IBA was divided into two parts, one representing the critical international debate against the post-war proposals to reconstruct the European cities, and the other representing the possibilities of rehabilitation and exploring the limits of citizens’ participation, in order to provide affordable housing:

The New IBA, with its Critical Reconstruction [

15] theoretical framework, was interested in materializing the international architectural debate. It was rather academic and never opened the debate to the citizens in the decision-making process. The proposals explored new ways to formalize the architecture of a city looking for autonomy or a separation from the economic powers; this was an autonomy that was proposed to review the notion of functionalism and typology in the design of housing and the city.

The cautious urban renewal of the Old IBA assumed a more pragmatic role, and aimed to materialize some of the changes that citizens required for a better standard of living. They proposed a dissolution of architecture among other agents, making the project more interdisciplinary and participatory.

4. Conclusions

In “The Production of Space” [

23], Henri Lefebvre proposed that the architect is the one capable of negotiating with the complexity of forces involved in urban construction, the conflicts between desires and interests, political or economic ambitions, as well as the pragmatic needs of the inhabitants of the space in conflict. This problem of the contemporary city was recognized not as a “general” problem of the city, but as a particularly serious problem in border neighborhoods occupied mainly by the working classes.

From the beginning of the 1970s, the model of urban reconstruction throughout Europe became a source of political confrontation. As analyzed in this paper, especially in West Berlin, the lack of land profitability in the areas surrounding the wall led to the abuse of the relationship established between the newness of modern architecture and the economy; this made the so-called “experience of modernity” traumatic because of the destruction or absence of inhabited spaces in use, from which their residents were evicted.

After the European Year of Architectural Heritage (1975) and the specific event celebrated in Berlin

Eine Zukunft für unsere Vergangenheit (1976), the IBA was born by establishing a consensus for the further reconstruction of the city and its structure of housing blocks. The idea of Cultural Heritage was being transformed, embracing the inhabited structures. Among the theoretical assumptions that underpinned both the Critical Reconstruction and the Cautious Urban Renewal, the following were particularly noteworthy agreements: [

23]

It was not the first time that Berlin was confronted with such a large-scale project. Three paradigmatic examples of the 20th century can be highlighted: The 1910 Great Urban Exhibition in Berlin; the 1931 The Housing of Our Days; and the 1957 Interbau, The City of the Future.

The IBA, unlike the previous exhibitions, began to be conceived with the purpose of recovering the lost population and the economic activity of the city [

15]. East Berlin was the

Hauptstadt der DDR (Capital

of the GDR), but the West had lost its functions, and with them, its proper urban articulation. It was isolated, and its strategic geopolitical location in the heart of central Europe made it, above all, a symbol of the Cold War.

The participating architects highlighted this fragmentary condition in projects executed as an attempt to reconcile opposites. According to Kleihues [

15], “the conception of plurality that characterizes the historical image of European cities can be realized even when modern and contradictory ideas are respected, not as a superficial classical need for harmony, but open to experimentation and contradiction.”

The third important theoretical presupposition is of the autonomy of the Architecture of the City [

18] as an opposition to the rhythms of urban transformation following the “needs” of the market.

After the 1973 oil crisis, the municipality decided to group large urban plots to offer sufficient profit margins to investment companies for the construction of housing. The Sanierung Plans based on the tabula rasa of the existing neighborhoods, were the most efficient in terms of profitability. The IBA was based on the idea that the proposals for the construction of the city should be independent and autonomous from the rules of the market.

The IBA defended Berlin’s historic urban configuration, characterized by the corridor street and the closed or semi-closed blocks with inner courtyards. It emphasized the mixture of functions in each quarter (leisure, work, housing), explicitly criticizing the assumptions of the 1957 Interbau. The IBA also defended a recovery of the pedestrian scale, establishing a clear differentiation between the public and private spheres, recovering the façade as a boundary element and the street as an actively structuring element. While the modern city was being constituted as a socio-functional phenomenon, this period of Berlin’s inflection offered an essentially formal and autonomous system from which a different approach to public space was intended to emerge.

The IBA established basic guidelines according to traditional patterns of alignment and height, but with stylistic freedom. The IBA reflected contradictions by wanting to be a system that eliminated any possibility of a global restructuring, but maintained the commitment to addressing the subsystems and fragments of the city. It was a program based on a critique of the postwar reconstruction projects and nostalgically suggested the renewal of a past order that was valued positively. This tendency was reflected in most of the commissioned projects, where the repetition of old morphological patterns and, in particular, the consolidation of the closed blocks of Hobrecht’s Berlin can be analyzed.

Apart from these common purposes, the two IBAs were differentiated. Urban architecture operating in these places cannot be neutral in the ideological debate on the transformation of the city. An illustrative example that shows that there was an ideological debate between the two approaches of the IBA can be read in the following statement of H.W. Hämer, director of the Old IBA [

24] (p. 70):

“The New IBA organizes a general idea of how the city should be. It is a different process from the Old IBA. It is a competition without the participation of the people, neither users nor neighbors. [...] Let’s take the example of Kluckstrasse; it is a street that ends at Kurfürstenstrasse; the New IBA wants to continue it up to Tiergarten, formally completing the grid of the neighborhood, but it does not take into account that, for that, one hundred and twenty families have to be evicted and several buildings have to be demolished. I mean that the formal idea does not correspond to the built reality. That is a bit of the difference between the two.”

From the study of these approaches to the reconstruction of Berlin, it can be noted that the problem of urban reconstruction after World War II was often relegated to a series of abstract data and codes. This became one of the most important debates in European architecture in the second half of the twentieth century.

The period that has been analyzed in this research could be considered as the time when the clearest criticisms against the ideas derived from the Modern Movement took place. This opposition to modernity began in the sixties, nourished by ideas born and grown in massive civil movements. However, from the eighties onwards they were captured by very different forces. Rem Koolhaas, for example, made reference to this in his famous chapter

Imagining Nothingness [

25]: “

It is ironic that in architecture, May ‘68 “under the cobblestones, the beach” has translated only into more cobblestones and less beach.”

The architecture that materialized in both IBAs was also influenced by the criticisms against the logic of the post-war modern city and was based on the critical revision of historical aesthetic models. This “aesthetic” response to the problem denied the existing social relations and the consequences they could have on the low-income classes living in the affected neighborhoods.

The Cautious Urban Renewal proposal, rather than presenting itself aesthetically, would face the reality of building in these neighborhoods; they would establish a negotiation with reality that, rather than being optimized under a simple logic, followed a more complex negotiating scheme under which the architect would have to compromise and decide before the different present forces, tensions and affected users. Finally, the proposal would deliberate, without being able to escape from the ideological commitment.