Architectural Heritage Analysis of the Yuanying Guan Pavilion: Construction and Signification

Abstract

1. Introduction

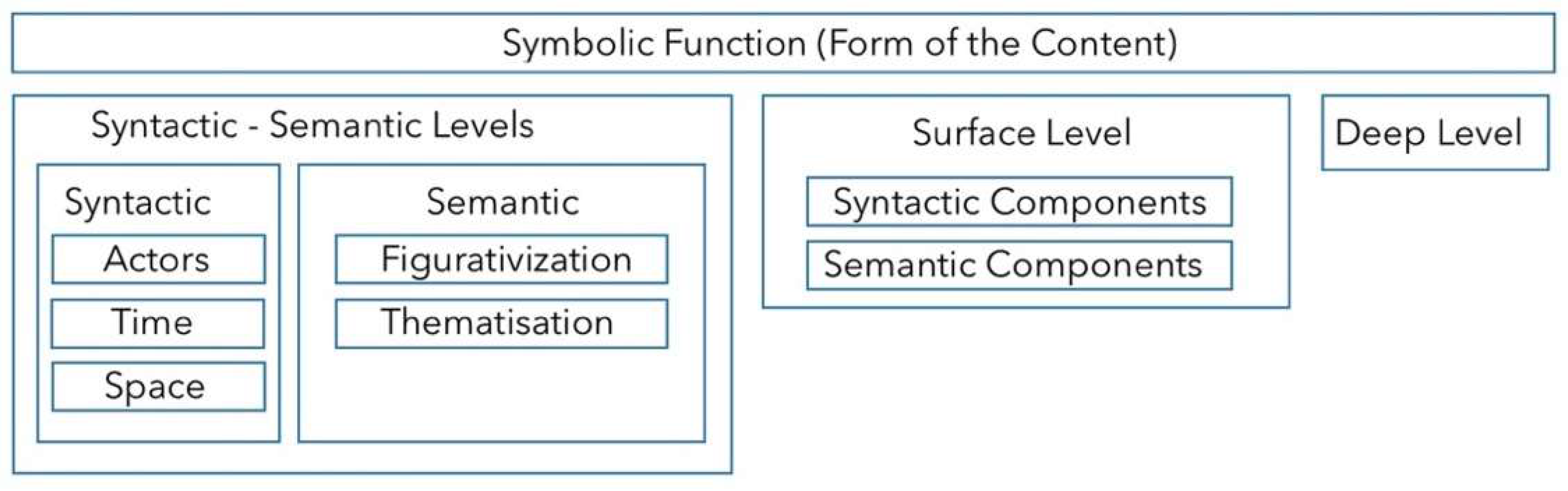

2. Theories of Semiotics

“What distinguishes architecture from painting and sculpture is its spatial quality. The analysis of this space, from semiotics, suggests that its meaning as a sign is generally understood in relation to different aspects and considerations.”

3. Analysis of the Yuanying Guan Pavilion

3.1. Introduction

“Dans la sale quil a fait nouvell mentbâtir pour placer les Tapisseries de la manufacture des Gobelins, que la cour de France lui envoyées en 1767, il y a partout des trumeaux magnifiques.”

3.2. Semiotic Analysis: Structural Function

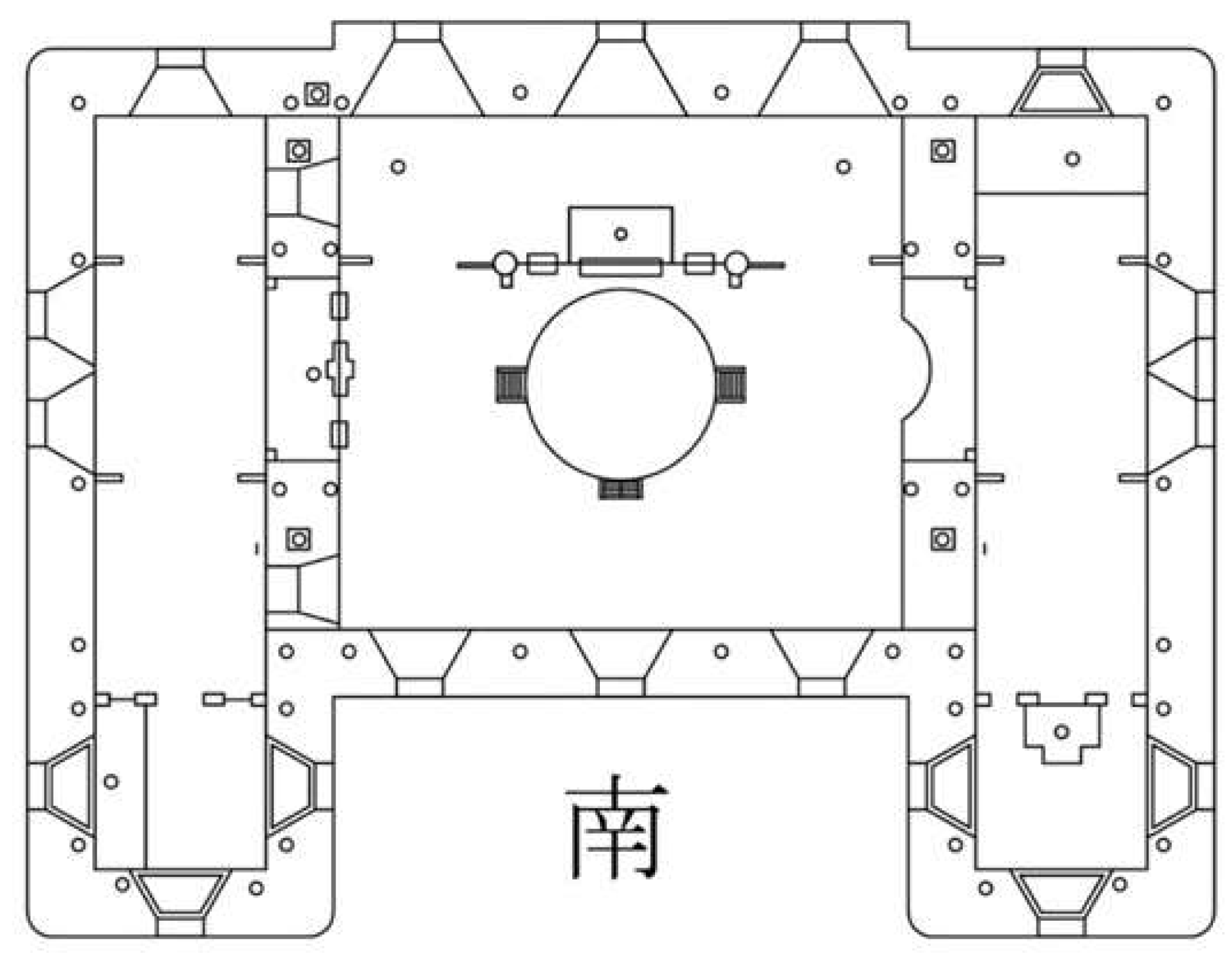

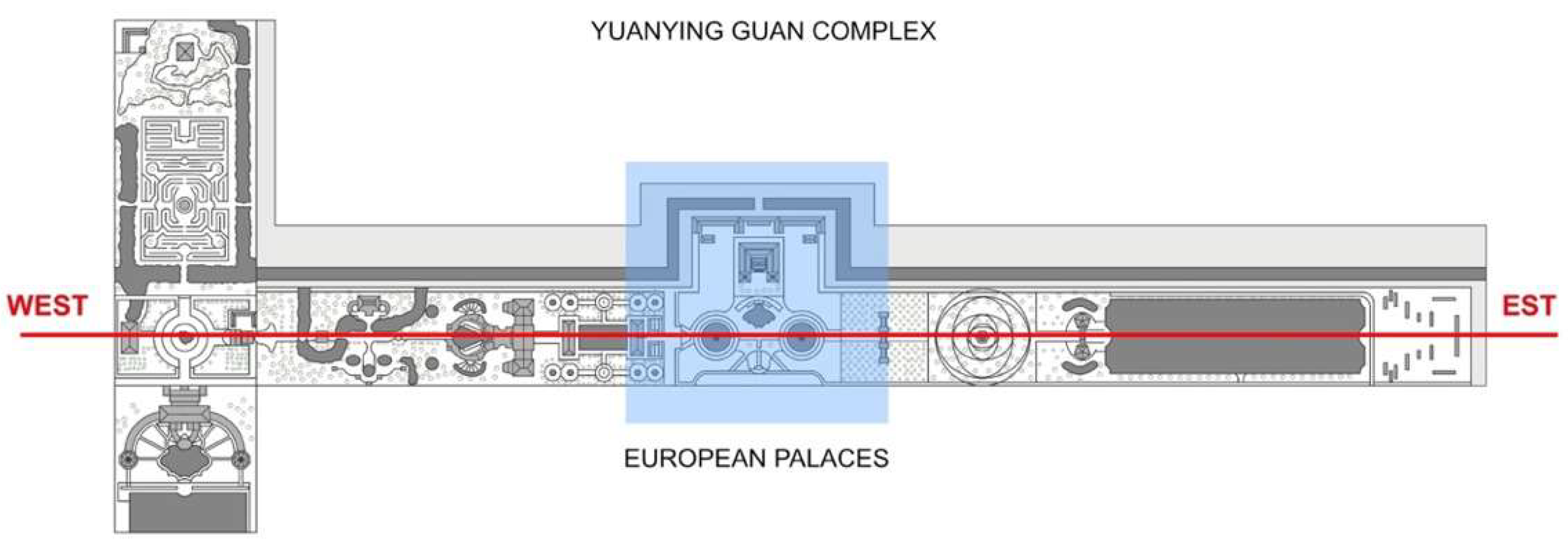

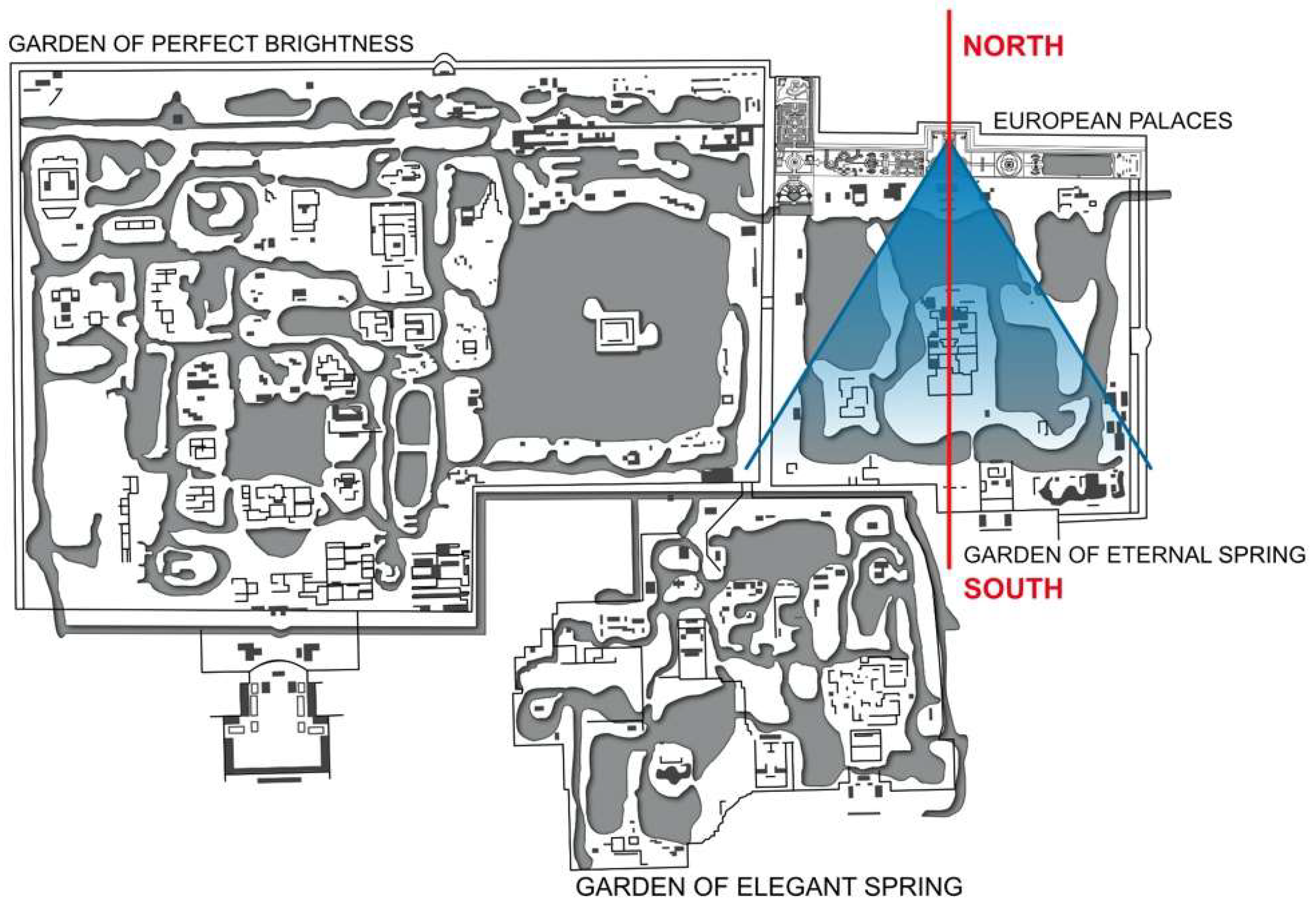

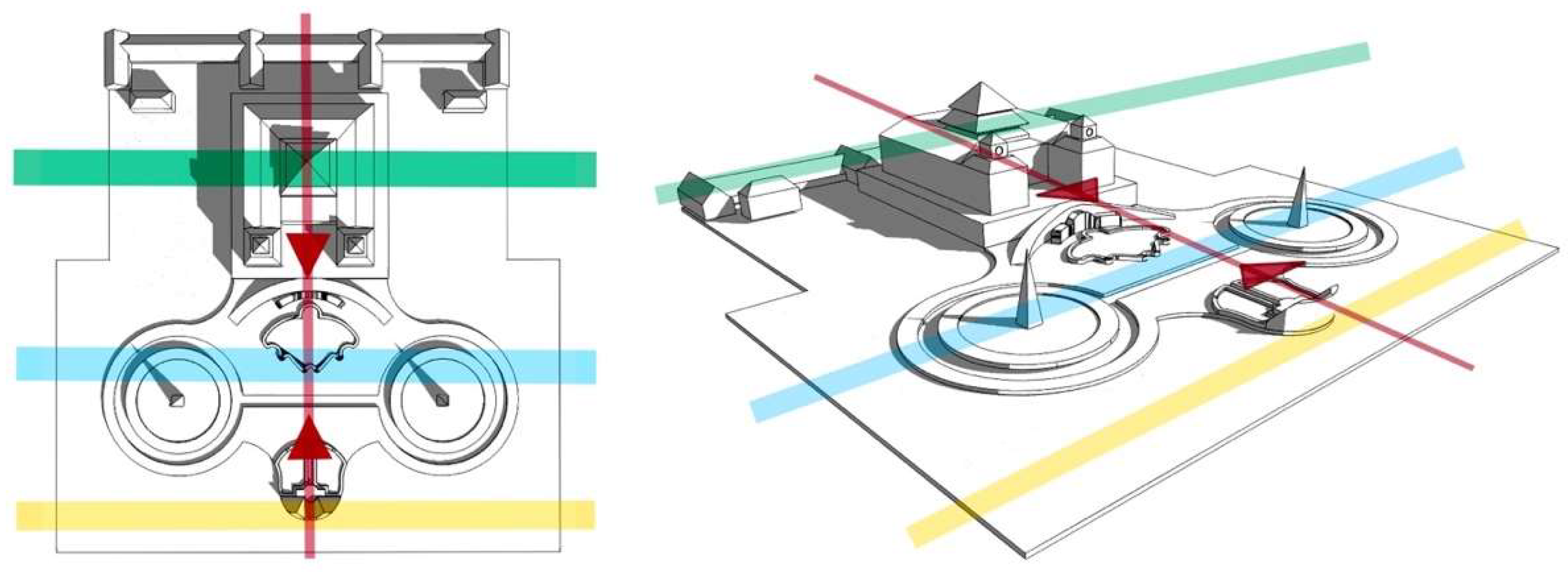

As the plan drawing of the View of the Distant Sea pavilion in the Model Lei collection illustrated there was a throne facing to the south in the central hall of this building. In the northern part of the hall there was a screen behind the throne to protect the emperor’s back. In the drawing, a Chinese character for “south” was specifically marked to accentuate the importance of the orientation to the south.

3.3. Semiotic Analysis: Symbolic Function

3.3.1. Actors

For an important building in a Chinese garden, such as a hall, two name boards were usually hung. One board was hung on the outer eave over the door so that people would see it when entering the building; the other board was hung on the inner eave over the central chair so that a visitor could view the board that hung over the host’s head. The meaning of a name board was closely related with its location: inside or outside. […] as well as “View of the Distant Sea”, which were all hung on the inner eaves of their respective buildings and became the official names of those buildings. In all these cases, the name board was hung over an imperial throne.

3.3.2. Time

3.3.3. Space

In modern–day China, when people hear the term yuanming (literally, round brightness), they probably think of two wonders: one is the bright full moon appearing at the middle of each month; another is the Yuanming Yuan, literally, Garden of Round Brightness, which exists only in their minds (A6).

“The rooms imitate the Western style.

My little heart includes the distant seas.

The imperial mind embraces the great world.” [21] (p.186).

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- A1.

- Different biblical texts like proverbs, parables, psalms, etc., use the leaf as an element that allows a wide and varied symbolic repertoire.

- A2.

- From an architectural point of view, the term “Liuli” always refers to the roof tiles of Chinese palaces. It is the main artificial material for the roof of these palaces. The main component of Liuli is clay. After heating the tile to high temperatures, it is covered with enamel to obtain different coloured forms. Likewise, “Taihu rock” is a type of natural rock from Lake Taihu. Its main characteristics are roughness and transparency.

- A3.

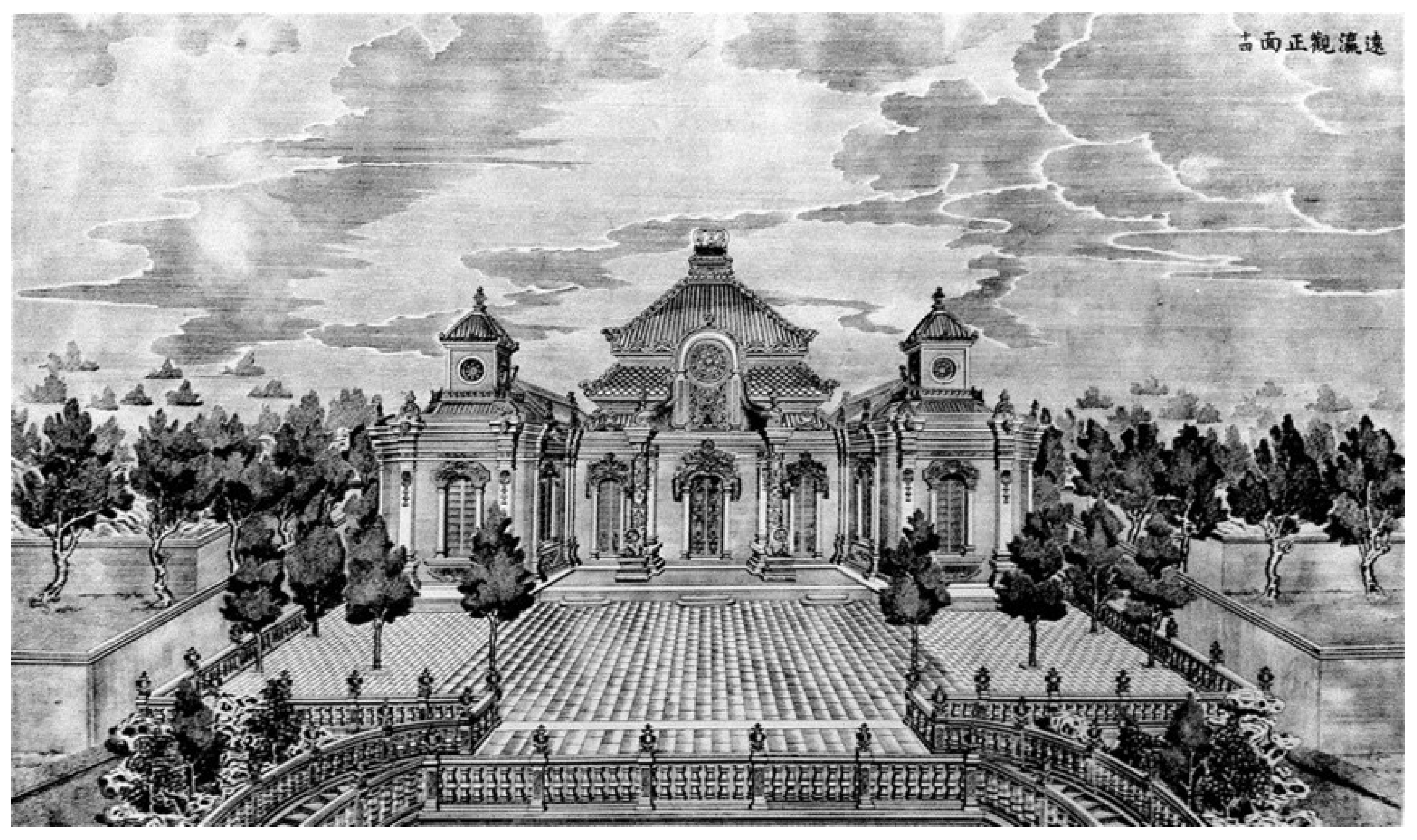

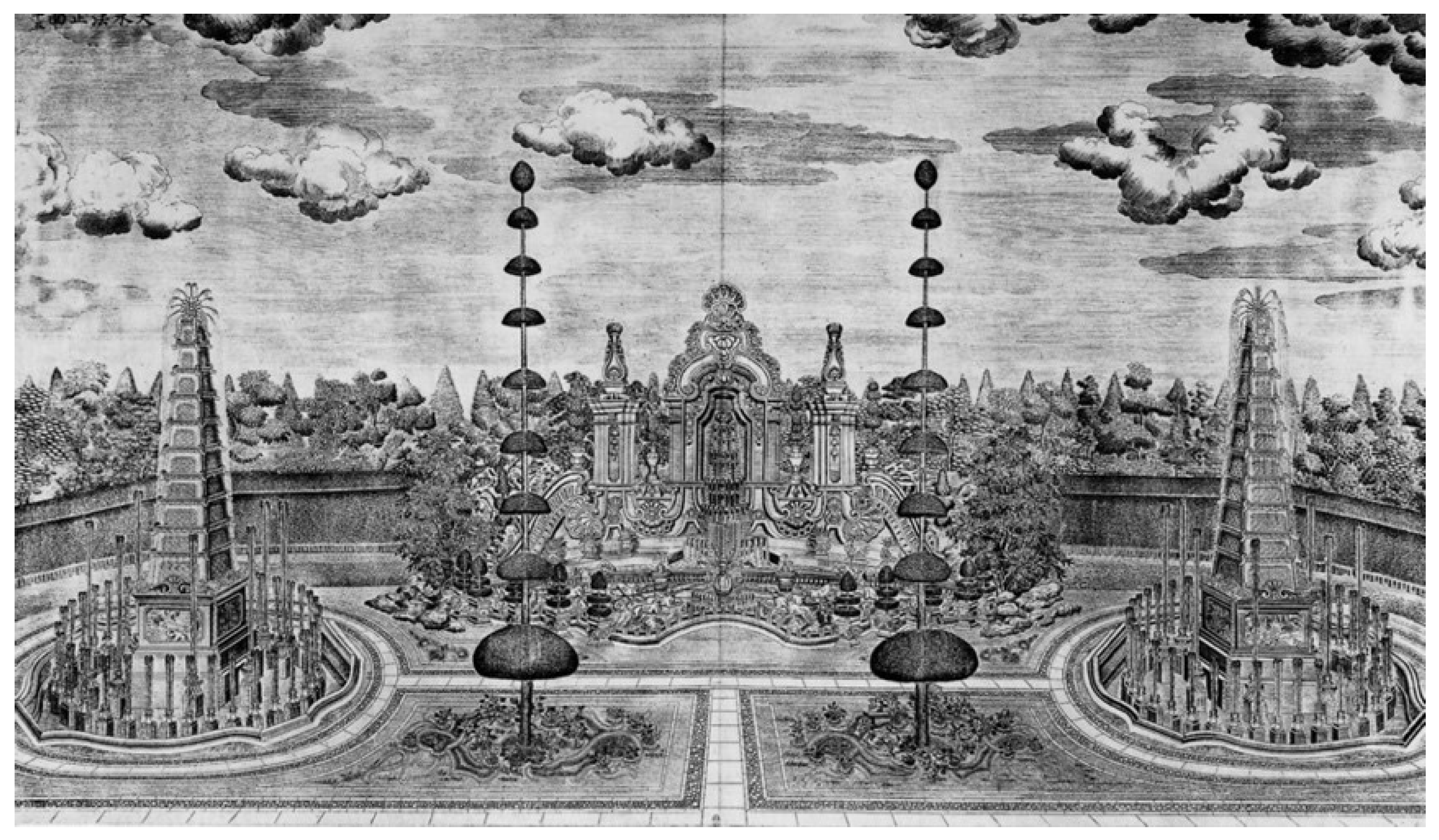

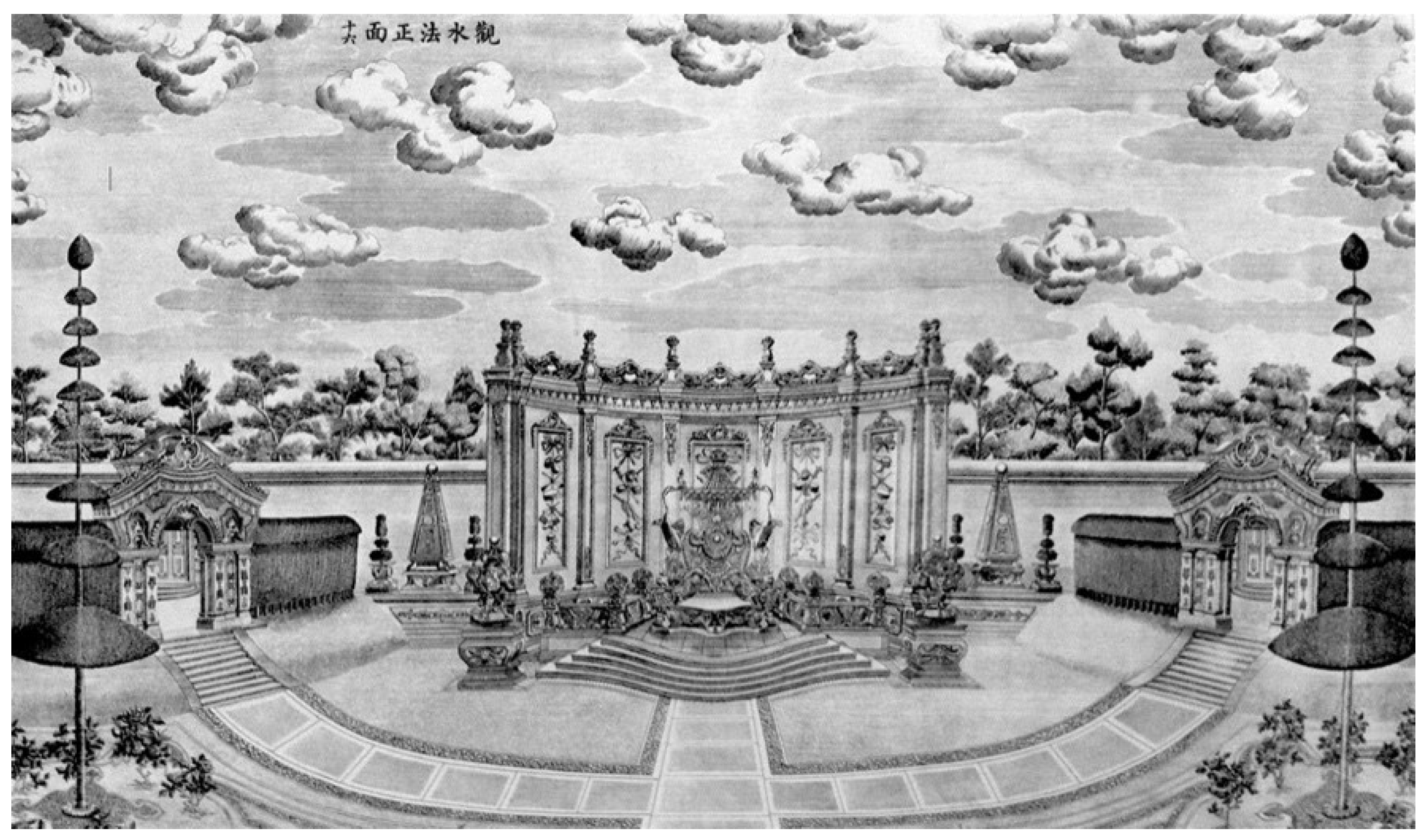

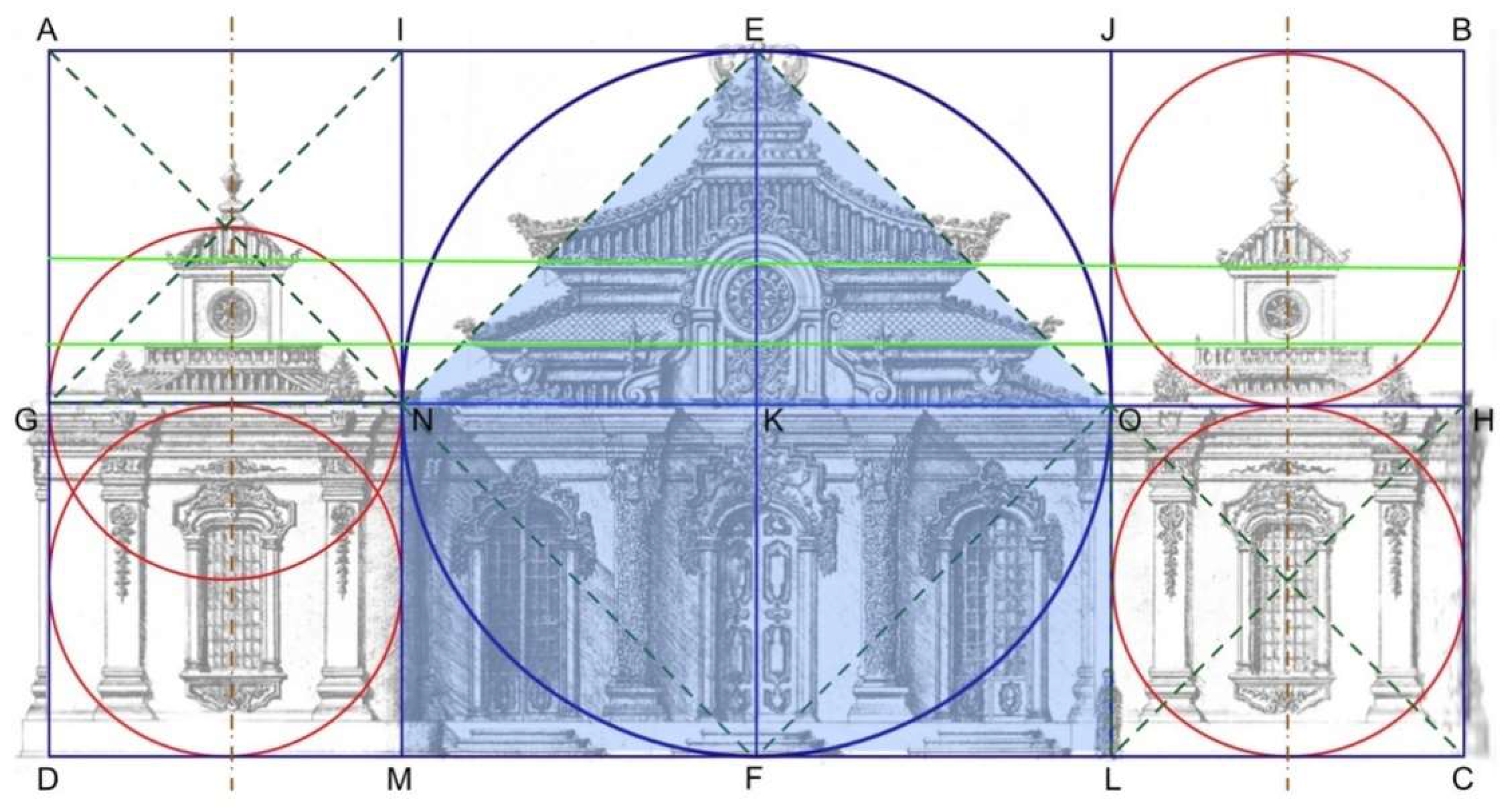

- Conceptually, the origin of the word rhythm could be traced back to the Greek concept of rhythmós. In Pollitt, 1974 [17], it is defined as a “repetition of elements at regular intervals”. There is no doubt that the existing palaces and gardens in the European Garden of Yuanming Yuan are distinguished by their rhythmic emphasis. An example of this is the View of a Distant Sea Pavilion (Yuanying Guan), in which Castiglione designed the facade as a symphony of columns and pilasters, with harmonious proportions and bilateral symmetry, as well as important decorative details in the Baroque style.

- A4.

- See L. Aimé–Martin ed. Lettres édifiantes et curieuses. Volume 4. Chine, Indo–Chine, Océanie. (Paris: Société du Panthéon Littéraire, 1843), 226.

- A5.

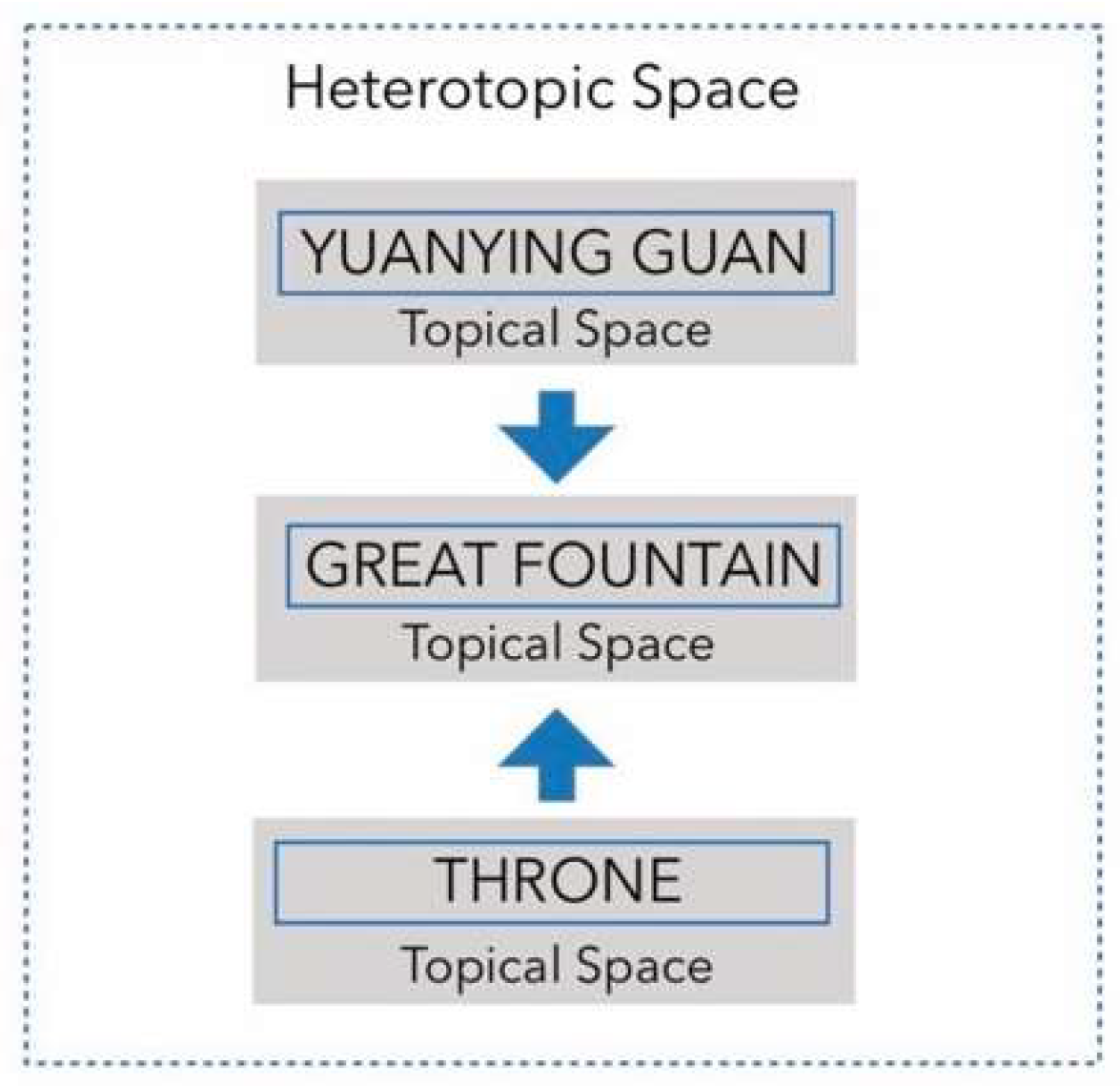

- “Topos” is derived from the Greek word, τόπος, “place”. Its plural is topoi. From a mathematical point of view, for Alexander Grothendieck, “topos” derives from modern mathematical category theory and constitutes the most perfect idea of the generalization of space. Category theory constitutes a generalization of set theory [22] (pp. 87–109). From the spatial point of view, a topos is a portion of space that can play a syntactic role. A rigorous definition of topos from the semiotic point of view can be seen in [23] (p. 116).

- A6.

- Due to its short life, its greatness and its small European Garden, the space occupied by the Yuanming Yuan is remembered as something unique in the history of Chinese gardens. For a large majority of Chinese people, the memory of this garden, savagely burned and looted by Anglo-French troops in 1860, is based on two strong emotions: fire and its ruins. This is the meaning that we suppose Zou wanted to give to his words.

References

- Laamann, P. The Inculturation of Christianity in Late Imperial China, 1724–1840. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 2000; pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ballano, V. Inculturation, Anthropology, and the Empirical Dimension of Evangelization. Religions 2020, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, M.V. Aesthetic interpretation and construction of an illusionist painting in the Qing dynasty: A semiotic approach to learning. J. Aesthetic Educ. 2020, 54, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D. Semiotics: The Basis, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 2–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotic; University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lukken, G.; Searle, M. Semiotics and Church Architecture; Kok Pharos Publishing House: Kampen, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pevsner, N. An Outline of European Architecture; Pengin Books: Baltimore, Maryland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, A.J.; Courtes, J. Semiotics and Language. An Analytical Dictionary; University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1982; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, A.J. Pour une semiotique topologique, Semiotique de l‘espace. Architecture, urbanisme, sortir de l‘impasse. In Semiotique et Sciences Sociales; Greimas, A.J., Ed.; Seuil: Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Greg, M.T. Yuanming Yuan/Versalles: Intercultural Interactions between Chinese and European Palace Cultures. Art Hist. 2009, 32, 115–143. [Google Scholar]

- Musillo, M. Reconciling two careers: The Jesuit memoir or Giuseppe Castiglione Lay Brother and Qing imperial painting. Eigtheeth-Century Stud. 2008, 42, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleutghen, K. Stanging Europe: Theatricality and Painting at the Chinese Imperial Court. Studies in Eighteenth–Century Culture; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, IN, USA, 2013; Volume 42, pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Delatour, L.F. Essais sur l’architecture des Chinois, sur Leurs Jardins, Leurs Principes de Médecine, et Leurs Murs et Usages; Imprimerie de Clousier: París, France, 1803. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H. Jesuit Perspective in China. J. Hist. Archit. 2001, 14, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pirazzoli–T’Serstevens, M.; Musillo, M. Giuseppe Caastiglione. 1688–1766, Peintre et architecte à la cour de Chine; Thalia Edition: Paris, France, 2007; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo, P. Identidad y globalización en las fachadas jesuitas de Pekín en el siglo XVIII. In Book La Compañía de Jesús y las Artes: Nuevas Perspectivas de Investigación; María Isabel Álvaro Zamora y Javier Ibáñez Fernández (coords.), Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014; pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, C. Symbolism in Chinese Porcelain: The Rockefeller Becquest. Metrop. Mus. Art Bull. 1962, 1, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Beurdeley, C.; Beurdeley, M. Giuseppi Castiglione: A Jesuit Painter at the Court of the Chinese Emperors; Charles E. Tuttle Co.: Rutland, VT, USA, 1971; pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, J.J. The Ancient View of Greek Art; Yale University Press: New Haven, Connecticut, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Minzhong, Y. (Ed.) Rixia juwen kao. Guji Chubanshe: Beijing, China, 2001; Volume 1, p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H. A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture. Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2011; pp. 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kleutghen, K. The Qianlong Emperor’s Perspective: Illusionistic Painting in Eighteenth Century China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, J.P. Topos como metaconstrucción para el diseño en Arquitectura: Del espacio analógico al metaespacio conceptual. Ph.D. Thesis, University Autónoma del Estado de México, Toluca, Mexico, 2015; pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, M. Le Semiotization de l’espace. Esquisse dúne maniere de faire. Actes Semiotiques. Rev. 2013, 116, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H. The Jing of Line-Method: A Perspective Garden in the Garden of Round Brightness. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Architecture, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, J. The Qianlong Emperor’s Western Vistas: Linear Perspective and Trompe l’Oeil Illusion in the European palaces of the Yuanming Yuan. Bull. De L’école Française D’extrême Orient 2007, 94, 159–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, M.V. The Cultural Heritage of Architectural Linear Perspective: The Mural Paintings in Nantang Church. Heritage 2021, 4, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juodinyté–Kuznetsova, K. Architectural space and Greimassian semiotics. Soc. Stud. 2011, 4, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Che Bing, C. Un grand jardin imperial chinois: Le Yuanming yuan, jardin de la Clarté parfait. Extrême-Orient Extrême-Occident. 2000, 22, 17–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurens, J.; Antariksa; Salura, P. Signification of Architectural Form–Meaning in Architectural Inculturation. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castilla, M.V. Architectural Heritage Analysis of the Yuanying Guan Pavilion: Construction and Signification. Heritage 2023, 6, 2421-2434. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030127

Castilla MV. Architectural Heritage Analysis of the Yuanying Guan Pavilion: Construction and Signification. Heritage. 2023; 6(3):2421-2434. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030127

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastilla, Manuel V. 2023. "Architectural Heritage Analysis of the Yuanying Guan Pavilion: Construction and Signification" Heritage 6, no. 3: 2421-2434. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030127

APA StyleCastilla, M. V. (2023). Architectural Heritage Analysis of the Yuanying Guan Pavilion: Construction and Signification. Heritage, 6(3), 2421-2434. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030127