River Beaches in Russian Cities: Examples of Soviet Legacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

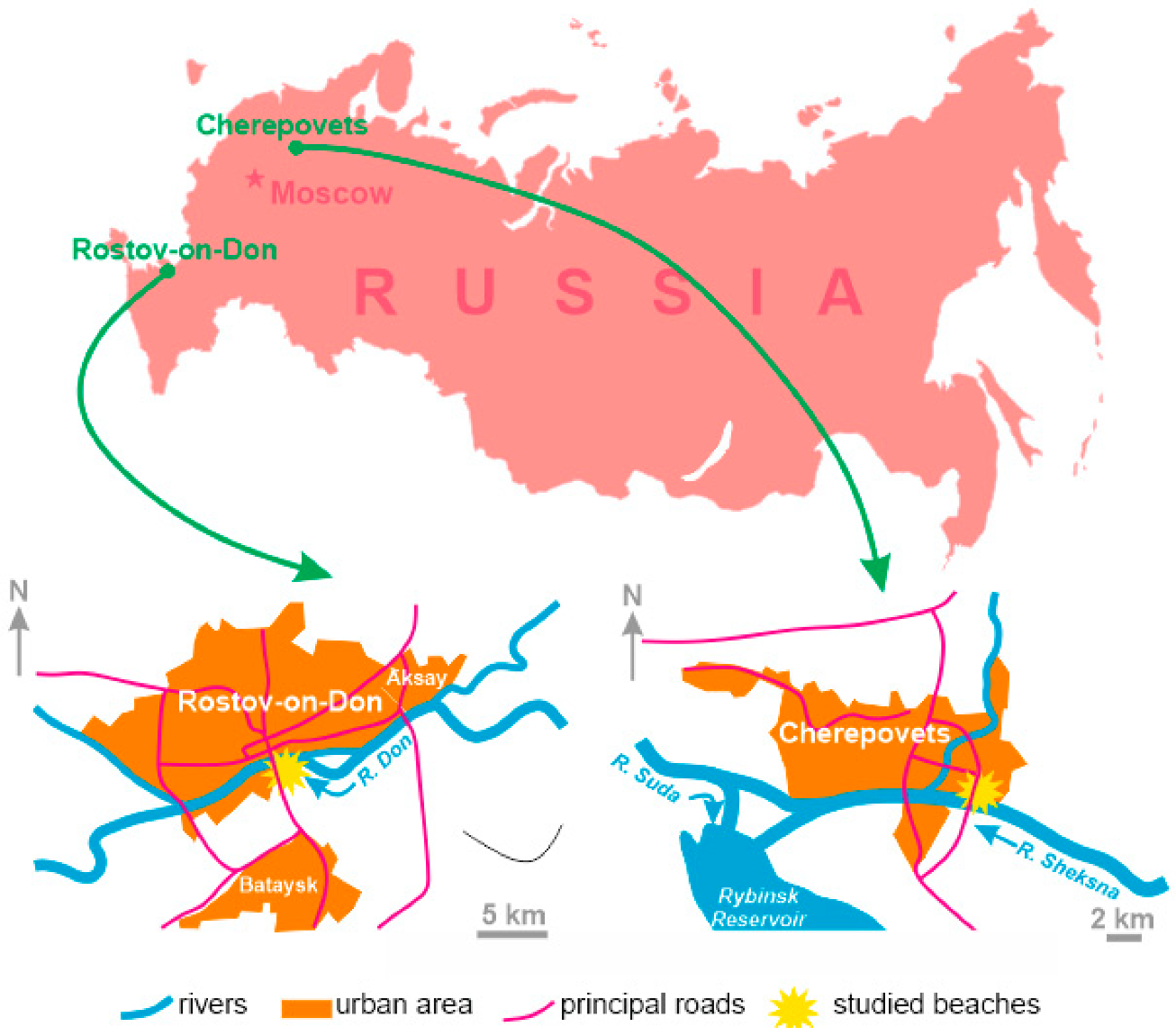

2. Studied Urban Areas

3. Methodology

3.1. Arguing Heritage Importance

3.2. Evaluating Aesthetics

4. Results

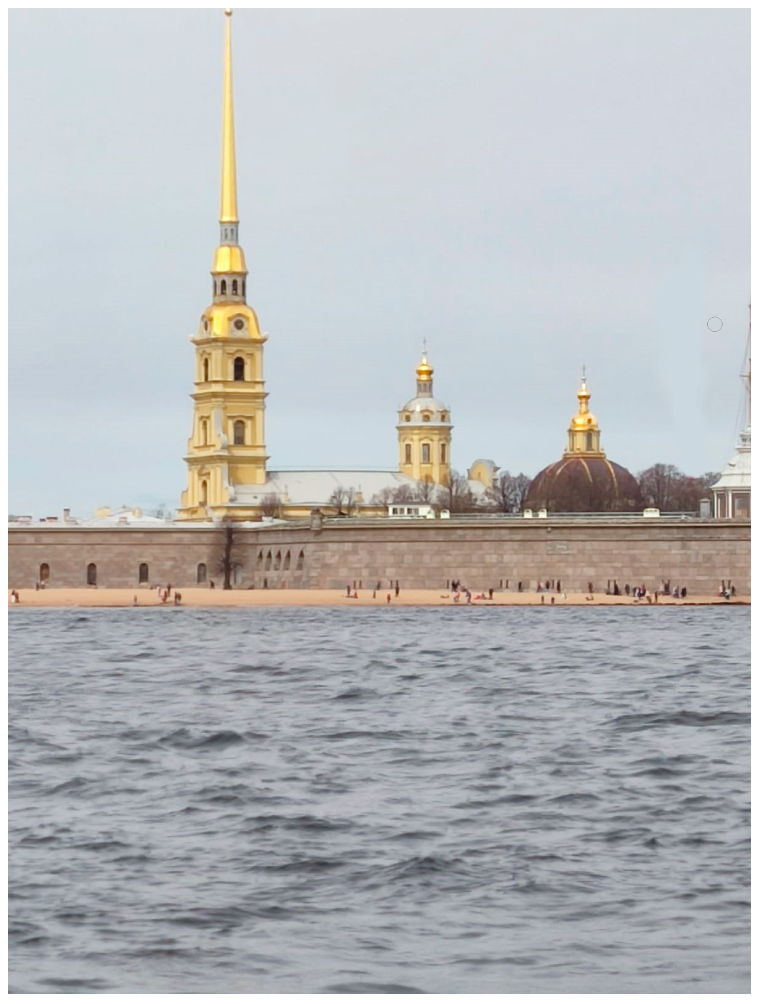

4.1. General Frame

4.2. Aesthetic Properties

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guzmán, P.C.; Roders, A.R.P.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Milne, S.; Fallon, D.; Pohlmann, C. Urban heritage tourism: The Gobal-Local Nexus. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, F. Conservation and rehabilitation of urban heritage in developing countries. Habitat Int. 1996, 20, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, L.; Mates, L. ‘It’s part of our community, where we live’: Urban heritage and children’s sense of place. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 1334–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailenko, A.V.; Ruban, D.A.; Ermolaev, V.A. Geoheritage meaning of artificial objects: Reporting two new examples from Russia. Heritage 2021, 4, 2721–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniewicz, P. Classification and Quantification of Urban Geodiversity and Its Intersection with Cultural Heritage. Geoheritage 2022, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylan, E. Cultural landscape and place attachment: Case of Van city (Turkey). Yuz. Yil Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 29, 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hajzeri, A. The management of urban parks and its contribution to social interactions. Arboric. J. 2021, 43, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuure-Stuip, G.A.; Labuhn, B. Urbanisation of former city fortifications in the Netherlands between 1805 and 2013. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2014, 143, 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Perez, J.J.; Solari, S.; Teixeira, L.; Alonso, R.; Neves, M.G. Propuesta de studio de la morfología determinada por el oleaje en playas fluviales. Geotemas 2015, 15, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T. Urban beaches, virtual worlds and ‘the end of tourism’. Mobilities 2009, 4, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondioni, E.; Corbari, S.; Feraboli, M.T. The renovation of the heliotherapy colony of Cremona and the riverside of the Modern: Ab itinerary toward the future. In HERITAGE 2014, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Guimaraes, Portugal, 22–25 July 2014; Amoeda, R., Lira, S., Pinheiro, C., Eds.; Greenlines Institute for Sustainable Development: Barcelos, Portugal, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1213–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Bratolyubova, M.V. Sport Societies and Leisure Time in Rostov-on-Don at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. Bylye Gody 2021, 16, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar]

- Agafonova, A.B. Greening of public spaces in Cherepovets during urbanization, 1870-1930s: Contradictions of sustainable development. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shomali, A.M. Establishing evaluation criteria of modern heritage conservation in historic city centers in Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2020, 11, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, B.R. Procedures and criteria for the definition of Global Heritage Stone Resources. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2015, 407, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.; Szuster, B.; Kaufman, A. Establishing consensus criteria for determining heritage tree status. Arboric. J. 2021, 43, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Varaprasad, K.S. Criteria for identification and assessment of agro-biodiversity heritage sites: Evolving sustainable agriculture. Curr. Sci. 2008, 94, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.M. Heritage protection criteria: An analysis. J. Plan. Environ. Law 2006, 7, 956–963. [Google Scholar]

- Dastgerdi, A.S.; de Luca, G. Specifying the significance of historic sites in heritage planning. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2018, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pătru-Stupariu, I.; Nita, A. Impacts of the European Landscape Convention on interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corinto, G.L. The European Landscape Convention and the Case of Italy after Twenty Years. Int. J. Anthropol. 2021, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- De la O Cabrera, M.R.; Marine, N.; Escudero, D. Spatialities of cultural landscapes: Towards a unified vision of Spanish practices within the European Landscape Convention. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1877–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Yang, Z. Evaluation for landscape aesthetic value of the Natural World Heritage Site. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajangam, K. Bridging Development and Heritage: Expert Gaze, Local Discourses, and Visual Aesthetic Crisis at Hampi World Heritage Site. J. South Asian Dev. 2021, 16, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, I. Urban sustainability, globalisation and the pursuit of the heritage aesthetic. Plan. Pract. Res. 1999, 14, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.T.; Ryan, C. Heritage and cultural tourism: The role of the aesthetic when visiting Mỹ Sơn and Cham Museum, Vietnam. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 564–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhambalova, S.G. Mongolian cultural heritage in UNESCO lists: Aesthetics of steppe mobility. Ural. Istor. Vestn. 2018, 60, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruban, D.A. Aesthetic properties of geological heritage landscapes: Evidence from the Lagonaki Highland (Western Caucasus, Russia). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2018, 68, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraboli, M.T. Dai fiumi al lago: Le colonie elioterapiche della provincial di Mantova negli anni Trenta del Novecento. In Il Sistema Ordoviario Mantovano; Pagliari, I., Ed.; DIABASIS: Parma, Italy, 2007; pp. 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Feraboli, M.T. Cremona City of Water: The River Architectures. In Putting Tradition into Practice: Heritage, Place and Design; Amoruso, G., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1010–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Štulhofer, A.; Marenić, Z.B.; Uchytil, A. Beaches and other sporting and recreational spots along the Sava in Zagreb. Hrvat. Vode 2010, 18, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lubysheva, L.I.; Pronin, S.A.; Korolkov, E.P. Historical prerequisites for the transformation of the theory of physical education into the methodology of sportization. Teor. I Prakt. Fiz. Kult. 2022, 5, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sakharov, V.A.; Sakharova, L.G. The formation of healthy life-style of Soviet youth in 1920s-1930s years. Probl. Sotsial’noi Gig. Zdr. I Istor. Medittsiny 2015, 23, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chechel, I.N.; Mikhailova, I.D.; Chechel, I.P. Reconstruction of cultural and leisure buildings of the Soviet period. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 944, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Haase, D.; Haase, A. Urban green space in transition: Historical parks and Soviet heritage in Arkhangelsk, Russia. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2016, 3, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonauskaite, D.; Abu-Akel, A.; Dael, N.; Oberfeld, D.; Abdel-Khalek, A.M.; Al-Rasheed, A.S.; Antonietti, J.-P.; Bogushevskaya, V.; Chamseddine, A.; Chkonia, E.; et al. Universal patterns in color-emotion associations are further shaped by linguistic and geographic proximity. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, S.; Botero, C.M.; Yanes, A. To clean or not to clean? A critical review of beach cleaning methods and impacts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 139, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Chasteen, C.; Madsen, A.; Helton, C.; Davies, A. Case studies and lessons learned from parks and preservation. Environ. Pract. 2017, 19, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. Urban Foodscapes and Greenspace Design: Integrating Grazing Landscapes Within Multi-Use Urban Parks. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 559025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaux, S.; Garneau, J. The sports park and urban promenade in the quais de Bordeaux: An example of sports and recreation in urban planning. Loisir Soc. 2016, 39, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, H. The Sadabad Park project in İstanbul–balancing garden heritage conservation and contemporary park design. J. Landsc. Archit. 2009, 4, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. The nature of urban heritage: The view from New Westminster, British Columbia. Anthropologica 2017, 59, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Directions | Scoring System |

|---|---|---|

| Color | Colorful—Dull | 0—property is almost absent (undetectable), 1—property matters to certain degree (no clear direction), 3—property determines the object’s identity (clear direction) EVALUATION TEMPLATES: (A) A given urban beach is unorganized, and it is not prone to waste accumulation => Property “Upkeep” is not suitable => Score 0 (B) A given urban beach attracts both young and old persons => Property “People’s Age” matters, but indefinitely => Score 1 (C) A given urban beach has just been constructed, and it boasts very modern infrastructure => Property “Novelty” is well-represented => Score 3 Grades of aesthetic power: 0–15—small, 16–30—moderate, 31–45—big, 46—60—outstanding |

| Pattern | Clear—Unclear | |

| Physical proportion | Grand—Quaint | |

| Visual cues | Abundant—Scarce | |

| Space | Open—Narrow | |

| Object’s age | Modern—Historic | |

| People’s age | Young—Old | |

| Hygienic condition | Clean—Dirty | |

| Upkeep | Well-kept—Run-down | |

| Sound source | Natural—Artificial | |

| Sound volume | Loud—Quiet | |

| Integrity | Authentic—Artificial | |

| Origin | Natural—Man-made | |

| Flow of visual cues | Cohesive—Out of place | |

| Variety of visual cues | Diverse—Alike | |

| Novelty | Novel—Typical | |

| Complexity | Simplistic—Complex | |

| Shape | Round—Angular | |

| Symmetry | Symmetric—Asymmetric | |

| Uniqueness | Unique—Ordinary |

| Properties | Rostov-on-Don | Cherepovets | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction * | Score | Direction * | Score | |

| Color | Colorful | 3 | Colorful | 3 |

| Pattern | 1 | Clear | 3 | |

| Physical proportion | 1 | 1 | ||

| Visual cues | Abundant | 3 | 1 | |

| Space | 1 | Open | 3 | |

| Object’s age | Modern | 3 | 0 | |

| People’s age | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hygienic condition | Clean | 3 | 1 | |

| Upkeep | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sound source | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sound volume | 1 | 1 | ||

| Integrity | Authentic | 3 | Authentic | 3 |

| Origin | Man-made | 3 | Natural | 3 |

| Flow of visual cues | 1 | Cohesive | 3 | |

| Variety of visual cues | Diverse | 3 | Diverse | 3 |

| Novelty | Novel | 3 | Typical | 3 |

| Complexity | Complex | 3 | Simplistic | 3 |

| Shape | Angular | 3 | 1 | |

| Symmetry | 0 | 0 | ||

| Uniqueness | Unique | 3 | Ordinary | 3 |

| Total scores/grade | 41/big | 38/big | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mikhailenko, A.V.; Mamiev, M.B.; Hanow, T.; Kashkovskaya, I.M.; Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. River Beaches in Russian Cities: Examples of Soviet Legacy. Heritage 2022, 5, 1974-1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030103

Mikhailenko AV, Mamiev MB, Hanow T, Kashkovskaya IM, Yashalova NN, Ruban DA. River Beaches in Russian Cities: Examples of Soviet Legacy. Heritage. 2022; 5(3):1974-1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030103

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikhailenko, Anna V., Mergen B. Mamiev, Toyly Hanow, Ilona M. Kashkovskaya, Natalia N. Yashalova, and Dmitry A. Ruban. 2022. "River Beaches in Russian Cities: Examples of Soviet Legacy" Heritage 5, no. 3: 1974-1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030103

APA StyleMikhailenko, A. V., Mamiev, M. B., Hanow, T., Kashkovskaya, I. M., Yashalova, N. N., & Ruban, D. A. (2022). River Beaches in Russian Cities: Examples of Soviet Legacy. Heritage, 5(3), 1974-1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030103