1. Introduction

The second half of the 19th century was, indeed, a time when exchanges and collaboration between archaeologists and architects acquired a dominant place, and Athens was the place par excellence where the meeting between these two fields prospered [

1]. Throughout this period, collaborations between archaeologists and architects working on ancient monuments, in Athens or elsewhere in Greece, became very important. These collaborations provided the foundations for works of major importance for their respective fields as well as for the history of art. By comparing the different approaches of French, English, Italian, and German architects and archaeologists, one can understand how their ways of constructing and interpreting monument designs are related to the political and cultural issues that correspond to the historical moments examined. The fact that the forms of philhellenism changed after the independence of Greece is closely related to the changes of the meaning of travel to Greece. Architects and their collaborations with archaeologists have played a significant role in these changing perceptions of philhellenism [

2]. Within such a perspective special attention should be paid to the comparisons within a trans-European network of different ways of interpreting ancient monuments [

3]. The shifts concerning the ways in which Greek antiquities are interpreted in different national contexts and periods go hand in hand with the mutations of the meaning that travel to Greece takes.

Pivotal, for examining the role that travel to Greece played for the

pensionnaires of the Villa Medici in the 19th century, is the analysis of the drawings they produced for their

envois during their stays in Greece [

4]. The term

pensionnaires refers to the awardees of a residency for fellows at the French Academy in Rome. This award is also known as the ‘Grand Prix de Rome’. The

pensionnaires were invited to reside in Rome for four years at the Villa Medici, which is also known as the French Academy in Rome, while engaging in study and creative work [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The competitions for the selection of the

pensionnaires are known as the

Grand Prix de Rome, and, as Alexander Griffin remarks in his recently published book entitled

The Rise of Academic Architectural Education: The origins and enduring influence of the Académie d’Architecture, were often considered as “the most important measure of a student’s ability at both the Académie and the École” ([

7], p. 6). The Académie des Beaux-Arts, which controled the École des Beaux-Arts starting in 1819, was in control of the

Grand Prix competitions as well ([

7], p. 152).

The

envois de Rome were the obligatory exercises of the awardees of the Prix de Rome, during their Italian stay at the Academy of France in Rome [

6,

7,

8]. The

pensionnaires were required to send their studies to France to be evaluated. They emerged at the end of the 18th century. Each

pensionnaire was required to send a work to Paris every year, where an evaluation was made. The main objective of this article is the analysis of the collaborations between the

pensionnaires of the Villa Medici in Rome and the members of the French School of Athens. The main objective of the article is to present how the revelations of archaeology, actively disseminated by the members of the French School of Athens, had an impact on certain

pensionnaires of the Villa Medici, who decided to devote their

envoi to the antiquities of Greece. Of great importance, for understanding the cross-fertilization between art, archaeology, and architecture during the 19th century, is the concept of

Gesamtkunstwerk, which is at the core of Richard Wagner’s work [

9] and refers to an understanding of the different forms of arts into a whole, which was dominant during the 19th century.

2. The First pensionnaires Who Travelled to Greece

The first pensionnaires who travelled to Greece were welcomed by the Société des Beaux-Arts, which was the original foundation of the French School of Athens. A decree signed a year after the opening of the French School of Athens concerned the creation of a section of fine arts, which was to provide lodging for the pensionnaires of the Academy of France in Rome during their stay in Athens. At the same time, this decree concerned the stay of the members of the French School of Athens at the Villa Medici for an internship, the duration of which, at the end of the century, was two months. The Beaux-Arts section of the French School in Athens, which was aimed mainly at welcoming the winning architects of the Grand Prix de Rome, who wished to dedicate their envoi to the ancient monuments of Athens or other Greek sites, remained open until 1874. Between 1845 and 1848, the pensionnaires made their trip to Greece during the third year. In 1848, the trip to Greece was postponed until the end of the fifth year. The interest of this cooperative work between archaeologists and architects lies in the fact that, although the two disciplines dealt with the same subject of study, the way in which each interpreted Greek antiquities differed. Although their points of view were different, their exchanges had a significant impact on the methods developed by archaeology and architecture.

While the French Academy in Rome, since the 17th century, had the mission of initiating its

pensionnaires to ancient and Renaissance art, Greece was not allowed as a destination for shipments from Rome until 1845, although it is a particularly important source of antiquities. I could refer, as an indication, to the fact that in 1835 Victor Baltard’s application for residence in Greece was refused [

10]. Three years earlier, in 1832, renewed excavations of the Acropolis of Athens had begun. During the same period, between 1831 and 1838, architect Abel Blouet published his work entitled

Expédition scientifique de Morée, ordonnée par le gouvernement français. Architecture, sculptures, inscriptions et vues du Péloponnèse, des Cyclades et de l’Attique [

11]. Other former

pensionnaires of the Villa Medici in Rome, who travelled to Athens after the end of their stay at the Académie de France in Rome, are François-Louis-Boulanger Florimond and Jean-Jacques Clerget. The first was sent to Athens, in 1847, by the Ministry of the Interior to raise the plan of all the buildings inherited from Greek antiquity [

12]. Blouet, a former resident of the French Academy in Rome, was the Director of the Architecture and Sculpture Section of the Morée Scientific Expedition. He dedicated this book to the memory of Julien David Le Roy, who had published

Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce in 1758 [

13].

Le Roy was, also, awarded the Grand Prix of Architecture, in 1750. In 1755, he undertook a trip to Greece, visiting the Cyclades, Athens, Piraeus, Sounion, Corinth, Thorikos, Sparta, and Delos. During his stay in Athens, he produced illustrations of many monuments, including the Acropolis, the theatre, the Thrasyllus monument, Hadrian’s library, the stadium, Hadrian’s aqueduct, the monument of Lysicrates or Lantern of Demosthenes, the Tower of the Winds, the Arch of Hadrian, the monument of Philopappos, and the Temple of Jupiter Olympian, among other monuments. In 1770, Le Roy published the second edition of his book on Greece, containing a response to the criticism of James Stuart, who had written

The Antiquities of Athens, published in 1762 in London, in collaboration with Nicholas Revett [

14]. Stuart and Revett, who both trained as painters and later became architects, had been sent to Athens by the London Dilettanti Society in 1751, to measure and draw the antiquities of Athens and draw up a map of the Acropolis. An examination of the debates between architects and archaeologists in the pages of the

Revue générale de l’architecture et des travaux publics [

15], in particular, are very useful for my study. The article pays special attention to the incidents that influenced the practices of these two disciplines, giving particular importance to the role played by Greek antiquities in the intellectual training of 19th-century archaeologists and architects as well as to the significance of travel to Greece.

3. From the Winckelmannian Image of Greece to Jacques Ignace Hittorf’s Polychromy

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, in the middle of the 18th century, forged an ideal Greek model, which was criticized during the second half of the 19th century. A text that intends to elucidate Winckelmann’s conception of the Greek ideal of beauty is Michael Baur’s “Winckelmann’s Greek Ideal and Kant’s Critical Philosophy” [

16]. In the aforementioned text, Baur highlights that, according to Winckelmann, “the beautiful in art and nature clearly has something to do with Platonic ideas and with the way in which such ideas are apprehended through a kind of ‘idealization’ or ‘projection’ in the understanding” ([

16], p. 59). Baur also highlights that, in Winckelmann’s view, “beauty in art teaches us how to observe beauty in nature and not the other way around” [

16]. Moreover, according to Winckelmann, “if we learn properly from the Greeks (if we first imitate their imitation rather than imitate nature directly), we may eventually come to see how our own activity of imitating nature can be understood-truly-as being nothing other than the activity of nature ‘rising above its own self’” ([

16], p. 65).

An aspect that should not be neglected is the role played by the revelations of archaeologists in this questioning of the Winckelmannian ‘image’ of Greece. The publication, in 1764, of Winckelmann’s

History of the Art of Antiquity (

Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums) had a significant impact on the image of Greece [

17,

18]. Another work by Winckelmann, which, also, played an important role in the creation of an ideal image of Greece, is

Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (

Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst) [

19,

20], originally published in 1755.

As Jan Blanc maintains, in “Winckelmann and the invention of Greece”, Winckelmann, in his

History of the Art of Antiquity [

17,

18], understands Greece “as a whole, as a unitary and homogeneous world of which he tries to give an account of the main principles through the study of its works of art” [

21,

22]. Blanc points out that “like Greece, Greek art is idealized by Winckelmann, who makes it the paragon of perfection” [

21]. The particularity of Winckelmann’s approach lies in the fact that he posits “a priori the absolute perfection of Greek art” [

21]. Blanc argues that Winckelmann “gives more importance to theory than to gaze”, while overcoming the dichotomy “between nature and the ideal embodied in Greek art” [

21]. For Winckelmann, “[t] he ancient Greece is therefore, and paradoxically, a world of nature” [

21]. Winckelmann’s approach was based on the thesis that Greek art is the direct product of nature. Symptomatic of this thesis are his following words:

Everything that has been inspired and taught by nature and art to promote the development of the body, to preserve, develop and beautify it from birth to full birth has been implemented and used to the benefit of the physical beauty of the ancient Greeks [

17,

18,

21,

22].

In 1852, Jacques Ignace Hittorff was elected a member of the Institut de France. Hittorff agreed with Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Antoine Quatremère de Quincy regarding the primacy of Greek art over Roman art [

3,

23,

24]. According to Ákos Moravánszky, “[t]he first important contribution to the discussion on polychromy in the context of the theory of imitation came from Antoine Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy, professor and

Secrétaire perpétuel (Secretary-for-life) at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, in the form of his monumental publication

Le Jupiter Olympien (1814)” [

25,

26,

27,

28]. As Moravánszky remarks, in

Metamorphism: Material Change in Architecture, “[i]n terms of architecture […] Quatremère de Quincy felt bound to Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s classical ideal of beauty” [

25]. An aspect that is worth mentioning is the fact that Winckelmann, Quatremère de Quincy, and Hittorff did not travel to Greece. However, their theories had a very big impact on the image of Greece in the fields of archaeology, architecture, and art history. As Johanna Hanink remarks, in

The Classical Debt: Greek Antiquity in an Era of Austerity, Winckelmann’s “aesthetic [was] […] never informed by encounters with actual Greeks (Winckelmann never visited Greece)” [

29]. Christopher Drew Armstrong, in “French Architectural Thought and the Idea of Greece”, remarks that “[f]or Quatremère de Quincy, ‘Greek’ was synonymous with ‘Classical,’ signifying an architecture based on the orders and governed by a regular system of proportions” [

30]. As Drew Armstrong highlights, Hittorff presented the outcomes of his investigations on polychromy at the Académie des Beaux-arts and the Académie des Inscriptions, in 1830. Moreover, he displayed his drawings at the Salon of 1831 [

30].

The fascination induced by Greek travel and the reinvention of ancient Greek monuments should be understood in conjunction with the interest aroused by the works of Hittorff on ancient polychromy and, especially, his article entitled “De l’architecture polychrome chez les Grecs, ou restitution complète du temple d’Empédocle dans l’acropole de Sélinunte”, published in 1830 in the

Annales de l’Institut de correspondance archéologique [

23], as well as his

Restitution du temple d’Empédocle à Sélinonte ou l’Architecture polychrome chez les Grecs, published in 1851 [

24] (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The impact of Hittorff’s theory concerning the polychromy of ancient Greek monuments, on the way in which the

pensionnaires of the Villa Medici in Rome drew the ancient monuments of Greece, is apparent in the views of the Parthenon by Alexis Paccard (1846), of the Erechtheion by Jacques Tétaz (1848), and, especially, in the watercolours of the temple of Aphaia in Aegina by Charles Garnier (1852). The particular interest of Hittorff’s studies on the polychromy of ancient Greek monuments lies in the fact that they combined the attentive gaze of the archaeologist with the creative gaze of the architect. An aspect that played an important role in the formation of this double gaze was the fact that Hittorff was, simultaneously, an architect and archaeologist. His interpretation of antiquities should be understood in relation to his intention to go beyond the imitation of how ancient Greeks coloured their monuments.

Another noteworthy figure for the dissemination of the polychromy of ancient Greek monuments is Gottfried Semper. The latter got acquainted with Hittorff’s work during his stay in Paris in the late 1820s. After his appointment as Professor of Architecture in Dresden, he published

Vorläufigen Bemerkungen über bemalte Architectur und Plastik bei den Alten (

Preliminary Remarks on Polychrome Architecture and Sculpture in Antiquity) (1834) [

31,

32], in which he related the polychromy of Archaic Greek architecture to the necessity to adapt the perception of its forms to the glare and visual qualities of the Mediterranean light [

33] (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). As Moravánszky remarks, in

Metamorphism: Material Change in Architecture, Semper, in the aforementioned book, refers to the fact that James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, during their survey on ancient Greek monuments in 1757, discovered that the monuments were coloured [

25]. Struart and Revett refer to this in

The Antiquities of Athens [

14].

4. The Neo-Greek Movement and Travel to Greece

The neo-Greek movement included painters Henri-Pierre Picou, Auguste Toulmouche, Gustave Boulanger, and Dominique Louis Féréol Papety, among others [

34]. The emergence of this art movement is related to the period in which the

pensionnaires-architects of the Villa Medici expressed a great interest in travelling to Greece. The rediscovery of Greece and its antiquities through painting, in the case of the neo-Greek current, and the

envois de Rome of the

pensionnaires of the Villa Medici devoted to Greek antiquities, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Aphaia, should be understood in the context of the emergence of Hittorff’s theory on the polychromy of the ancient Greek monuments in the 1830s and the appearance of the archaeological discipline [

35], as well as the fascination accompanying the processes of archaeological excavations [

36].

Among the neo-Greek painters awarded the

Grand Prix who travelled to Greece is Dominique Louis Féréol Papety. One of his most famous paintings is the

Rêve de bonheur, exhibited at the Salon of 1843. Papety was influenced by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who was the Director of the Villa Medici in 1837, when the young artist arrived there. He made a trip to Greece, four years after the end of his residence, in 1846, the year of the opening of the French School of Athens [

37]. His painting titled

Le duc de Montpensier visitant les ruines du temple de Jupiter à Athènes (1847) (

Figure 5), painted after his journey to Greece, is characterized by a different view of ancient monuments and the ‘image’ of Greece in general, than that of his

Rêve de bonheur (1831) (

Figure 6). The comparison of the perception of Greece in these two paintings leads to a better understanding of the impact on Papety of his Greek trip. He travelled to Greece with the collector François Sabatier, of Espeyran Sabatier-Ungher, who he had met during his stay in Rome. During their stay, they visited twenty-three monasteries on Mount Athos [

38], Corfu and the other Ionian Islands, the Peloponnese, Delphi, and Athens.

Papety, returning to France, brought with him a large number of drawings that constitute a complete and detailed pictorial account of this trip. In parallel, he published “Les peintures byzantines et les couvents de l’Athos” in the

Revue des Deux Mondes, a monthly magazine devoted to literary, cultural, and political affairs, published in Paris since 1829 [

39]. This article was an account of his trip to Greece and a testimony to the growing interest of French painters in Hellenism. The fact that this article was published in 1847, a year after the founding of the French School of Athens, is not a coincidence. It is worth noting that the new archaeological school was founded by the Société des Beaux-Arts. The first members of the French School of Athens came from the École Normale Supérieure. The affirmed intention, “to create in Athens an institution which could, in the future and in the order of literary studies, become the analogue of our Academy of France in Rome” [

40], is of particular interest in this context.

One of the aspects of the neo-Greek movement in painting that should be highlighted is its characteristic intention to, simultaneously, break with neoclassical and romantic traditions, adopting an antiacademic approach. With regard to the neo-Greek movement in architecture, one can also distinguish such features in the case of Garnier’s representations, among others. The approach of the neo-Greeks is part of the renewal of interest in Hellenism. Since 1845, artists staying at the Académie de France in Rome had the opportunity to visit Greece. The first

pensionnaires who chose Greece for their third-year

envoi after this authorization were Theodore Ballu, the first

pensionnaire to visit Greece, and Alexis Paccard. During their stay, each resident had to represent an ancient monument and, in addition, propose a restoration. These two architects had already produced drawings of the Acropolis, before the foundation of the French School of Athens [

41].

5. Around the Collaboration between Charles Garnier and Abel Blouet

An important case of a collaboration between an archaeologist and architects during the 19th century is that between the French archaeologist (and politician Charles Ernest Beulé) and the architects Denis Labouteux, Louis Victor Louvet, and Charles Garnier [

41]. Charles-Ernest Beulé was the successor of Raoul Rochette at the Bibliothèque Impériale. Garnier was a

pensionnaire at the Académie de France in Rome, between 1848 and 1854. During this period, he visited Greece and Turkey. Of great importance for the dissemination of the polychromy of ancient Greek monuments are his colourful drawings of the Temple of Aphaia in Aegina. After his return to Paris, Garnier collaborated with Theodore Ballu. Charles-Ernest Beulé was the successor of Raoul Rochette at the Bibliothèque Impériale. He was appointed professor there in 1854, that is to say, the year that Garnier returned to Paris. According to Drew Armstrong, “Beulé […] reconciled the different factions in the debate over polychromy by suggesting that the more or less extreme use of paint on ancient Greek temples could be ascribed to different historical periods in the development of Greek architecture” [

30]. Beulé was supported by Labouteux, Louvet, and Garnier during his excavations of the Propylaea. Another noteworthy example of collaboration between an architect and an archaeologist during the 19th century is the case of architect Emmanuel Pontrémoli and archaeologist Maxime Collignon, who at the time of their collaboration were, respectively, a former

pensionnaire of the Villa Medici and a former member of the French School of Athens [

42,

43].

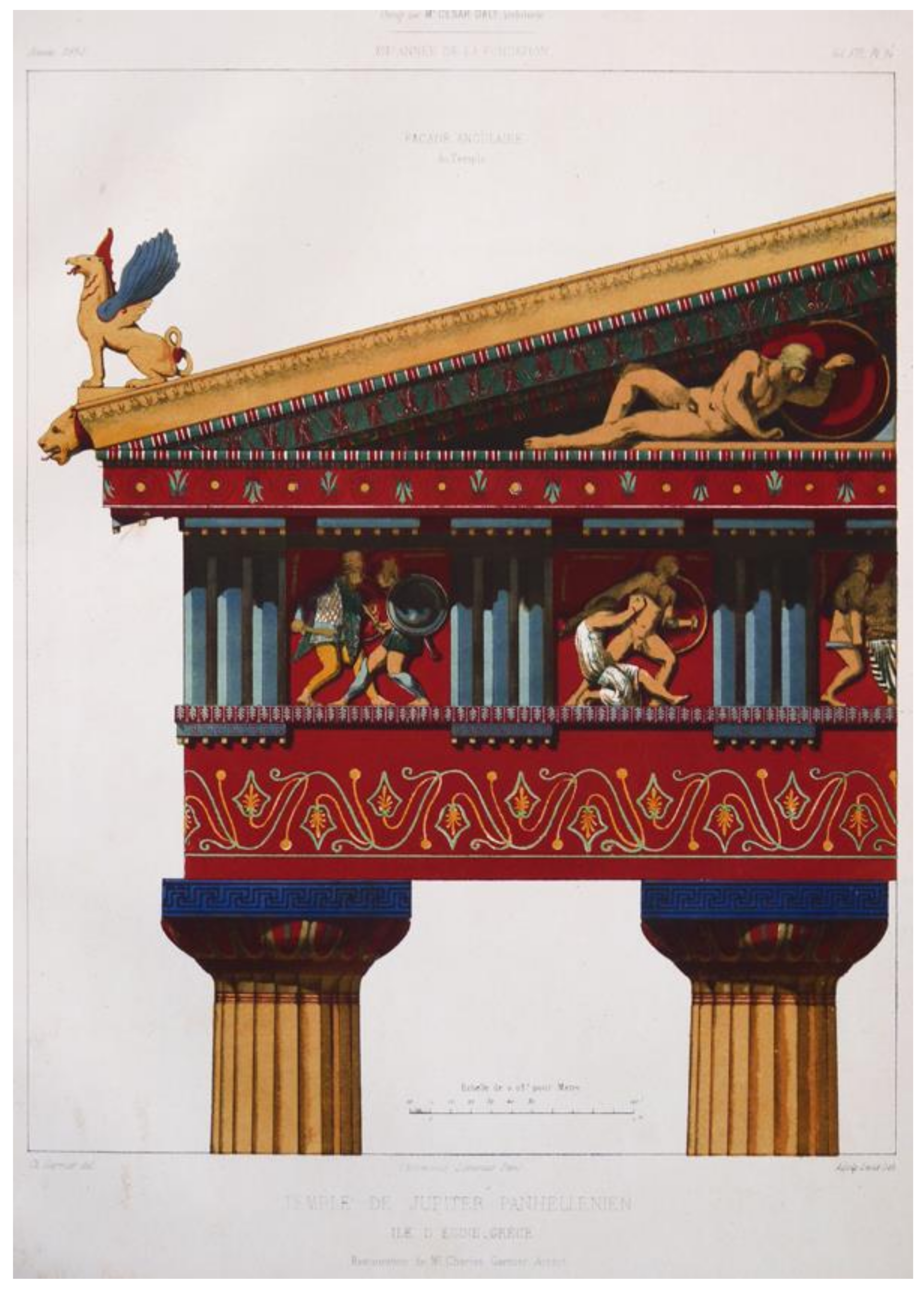

Garnier’s colouring in his representations of the Panhellenian Temple of Jupiter in Aegina constitute one of the most characteristic cases of the application of Hittorff’s theory (

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Garnier had consulted the writings of Pausanias as well as Blouet’s

Expédition scientifique de Morée, ordonnée par le gouvernement français. Architecture, sculptures, inscriptions et vues du Péloponnèse, des Cyclades et de l’Attique [

11], while he was working on his watercolours of the restored views of the temple of Aphaia in Aegina. Garnier produced these watercolours for his fourth-year

envoi de Rome, comprising fourteen drawings. He spent 21 days in Aegina, to closely study the temple of Aphaia. Garnier’s studies of the temple of Aphaia in Aegina concerned his

envoi de Quatrième année. During the same year, that is to say, in 1853, Denis Lebouteux devoted his own

envoi de Quatrième année to the study of the temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae. Garnier travelled to Greece in the company of the writer Edmond About. Edmond About was appointed a member of the French School of Athens, in 1851, and stayed in Greece for two years. About is among the most-known members of the École française d’Athènes. His book, entitled

La Grèce contemporaine [

44], was published in 1855. Garnier, after his return to Paris, presented his envois—that is to say, his colourful drawings of the Temple of Aphaia—at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, in October 1853. He, also, showed his watercolours at the 1853 Salon and the Exposition Universelle de Paris, in 1855 ([

45], p. 374).

Beulé was, like Garnier, convinced by the theory of polychromy developed by Hittorff [

46]. Hittorff and Raoul Rochette expressed their reservations about the methods used by Garnier in his work on the temple of Aphaia. In spite of these sceptical remarks, Garnier’s drawings had a major impact on architectural circles in Paris. Symptomatic of the way in which the drawings of the temple of Aphaia by Garnier played an important role, with regard to the exchanges between architects and archaeologists, is the fact that two chromolithographies of his reconstruction of the temple of Aphaia appeared in the pages of the

Revue générale de l’architecture et des travaux publics, to illustrate a collection of articles by Beulé [

15,

46,

47], who succeeded Rochette as professor of archaeology at the Bibliothèque Impériale in 1854.

Beulé and Garnier met in Athens in 1852, during the period when the first was a member of the French School of Athens and responsible for the excavations that uncovered the base of the Acropolis on the side of the Propylaea. Pivotal for understanding the importance of Beulé’s excavation work in the Acropolis is the article entitled “Résultats définitifs des fouilles de M. Beulé à l’Acropole d’Athènes”, published in the

Revue Archéologique in 1853 [

48]. In the same year, Beulé’s

L’Acropole d’Athènes was, also, published [

49]. Indicative of his point of view regarding the role of architects are the words of Beulé in his eulogy for Hittorff: “by dint of exactitude, delicacy, eclecticism, our architects are no longer content to be learned; they have become archaeologists” [

50,

51]. These words are revealing, concerning how the practices of architects were transformed in order to meet the needs of archaeological work.

6. Towards a Conclusion: Philhellenism and the Mutations of the Meaning of Travel to Greece

An analysis of the mutations of the forms of the “return to Arcadia”, to borrow the expression of Christine Peltre [

52], could help us better understand the transformations of the concept of philellenism. Useful for understanding the symbolic meaning of travel to Greece within architecture and painting is the idea of the “Grand Tour”, which refers to the educational journey for aristocrats that emerged around the middle of the 16th century and asserted itself throughout the 17th century, culminating in the 18th century [

16,

17]. There are certain affinities between the 19th-century travel to Greece for architects and the idea of the “Grand Tour” [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Of pivotal importance for the comparison of the different conceptions of philhellenism, within different national contexts, is the foundation of institutes devoted to the study of ancient Greek monuments in Athens. The École française d’Athènes, which is the oldest foreign archaeological school in Greece, was founded in 1846. Many scholars relate the foundation of the École française d’Athènes to the tradition of the

Expédition scientifique de Morée, ordonnée par le gouvernement français. Architecture, sculptures, inscriptions et vues du Péloponnèse, des Cyclades et de l’Attique [

11]. The Athens School of Fine Arts was established ten years earlier, in 1836. Athens was chosen as the capital of Greece in 1834. The section of Beaux Arts of the École française d’Athènes opened in 1859 [

57]. In the second half of the 19th century, however, the artistic centre of Europe moved from Munich to Paris. The Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Athen was founded in 1874. The American School of Classical Studies was founded in Athens in 1881. The British School of Athens was founded in 1886.

Among the most-known books related to philhellenism in France during the 18th century are Pierre Augustin Guys’s book, entitled

Voyage littéraire de la Grèce,

ou Lettres sur les Grecs anciens et modernes, which was originally published in 1771 [

58], Abbot Jean-Jacques Barthélemy’s novel entitled

Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis en Grèce, published in 1788 [

59], and Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier’s volumes entitled

Voyage Pittoresque de la Grèce, published between 1782 and 1822 [

60]. Despite the fact that there were several expressions of philhellenism during the 18th century, as Evangelos Konstantinou remarks, in “Graecomania and Philhellenism”, “European enthusiasm for Greece reached its climax in the early-19th century” [

61].

Note sur la Grèce of François-René de Chateaubriand [

62] and

Lettres sur la Grèce: notes et chants populaires [

63] of Olivier Voutier are important books for philhellenism during the 19th century.

The Greek Revival movement was more present in England, the UK, and Austria than in France. Greek independence played an important role in the development of approaches that related the ideals of beauty and nature in the arts and the forms of ancient Greek monuments [

64,

65]. Moreover, Greek independence contributed to the intensification of the interest in the excavations of Greek antiquities [

66,

67,

68,

69]. The independence war of the 1820s and the establishment of a Greek independent nation in 1831 contributed, significantly, to the development of interest in the excavations of antiquities, on the one hand, and to the fascination about the ideals related to the creation of the ancient Greek monuments, on the other hand.

To avoid an internalist and formalistic way of interpreting these drawings of the ancient monuments in Greece, one should try to illuminate how their exchanges with archaeologists and specialists of other disciplines (and belonging to other cultures) influenced their way of producing representations of ancient monuments. During the “pre-philhellenic” and “pre-romantic” periods, an imaginary link was perceived between the utopian aspect of Greece and classical studies. During the romantic period, the trip to Greece had a mythical character, which changed after the independence of Greece. Examining the ways in which the pensionnaires of the Villa Medici drew their envois de Rome, devoted to ancient Greek monuments, one can understand the successive changes in the way they interpreted the ‘image’ of ancient Greece. To understand architects’ interactions with archaeologists, it is important to investigate the social and intellectual environments with which they engaged, during their stays at the Villa Medici in Rome and in Greece.

Analysing the influence of archaeological discoveries on architecture during the 19th century, with a focus on the pensionnaires-architects of the Villa Medici and their travels to Greece, one can grasp the cultural and aesthetic mutations, concerning the way perceiving ancient monuments goes beyond the fields of the history of architecture and archaeology. These mutations can only be grasped by broadening the analysis of these reorientations, to the realms of political and cultural history, and by juxtaposing the points of view of different national contexts in the fields of archaeology and architecture.