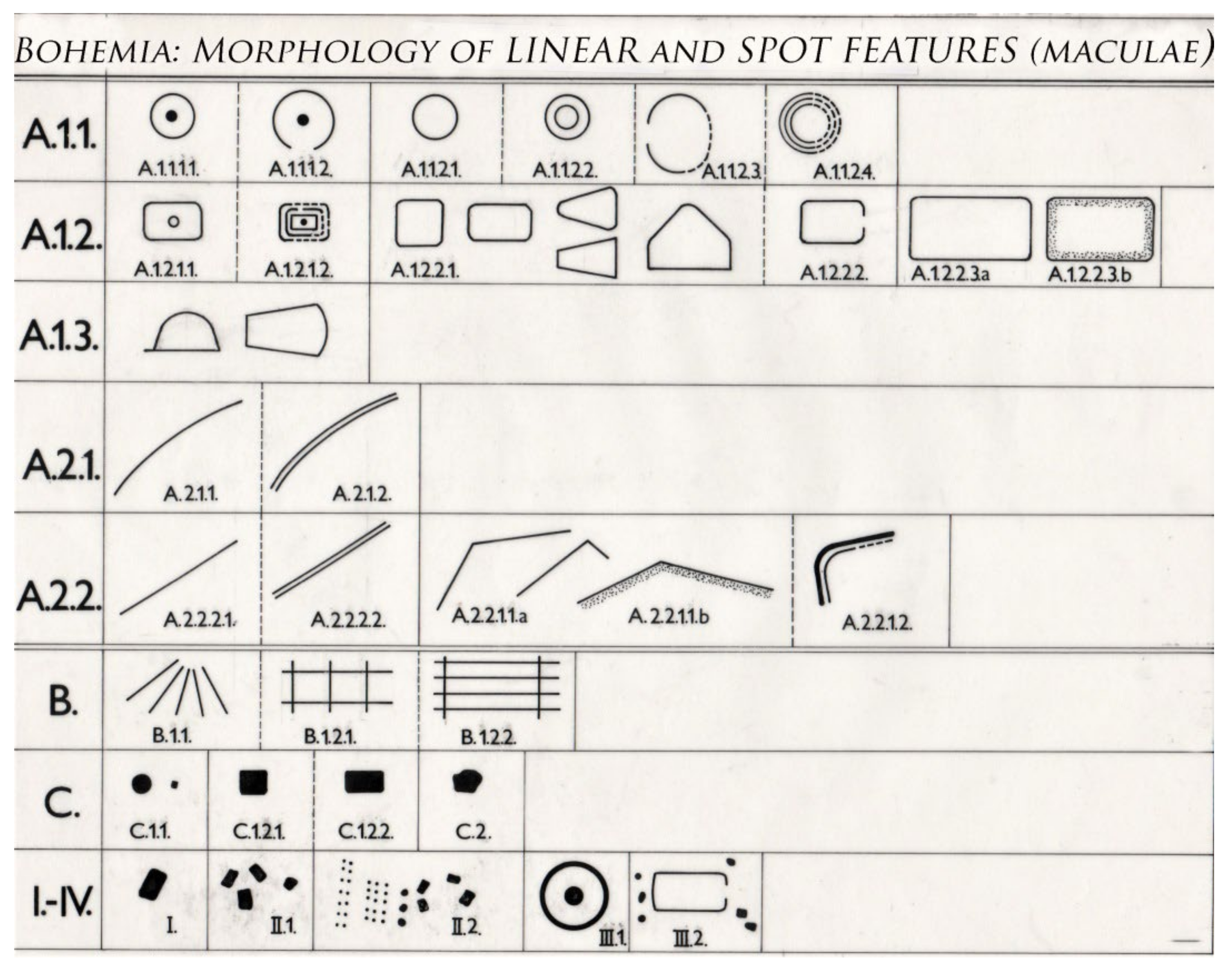

2.2. Spatially Arranged Groups of Postholes in Early Iron Age Settlements (Bohemia)

In the last fifteen years, the age of aboveground (not recessed below the ground surface) excavations has repeatedly documented structures formed by a regularly arranged set of postholes in the Czech Republic. One variant of this type is represented by features formed by regularly spaced postholes in a 4 × 3 pattern. In contrast, other features have a set of postholes enclosed by lines indicating either the former trench for the foundation of the structure or a trench for a palisade enclosing an aboveground structure with twelve posts.

This type of structure has been repeatedly identified by aerial survey in Bohemia in the middle and especially the lower reaches of the Elbe (most often in the flat alluvial valley of the river between Neratovice and Litoměřice and on elevated plateaus of the wider surroundings of solitary Mt. Říp—a central point of the historical Bohemian landscape, shrouded in legend and traditionally linked to the arrival of the Slavs in Bohemia [

15], and also in the eastern part of central Bohemia (

Figure 3, area 1). From the first discovery of vegetation marks of the described type of immovable relics in the late 1990s up until the previous decade, it was not clear how to interpret them and—above all—how to handle their dating. This was possible to determine due to results achieved by excavations. In this period during the rescue excavation of the Kolín bypass road, the grouping of several of these features was examined by field excavation. Within the framework of a number of development-led excavations in 2004–2016, the presence of postholes arranged in the same way was discovered near Roudnice nad Labem, in Prague-Miškovice and at several sites in the Pitkovický Stream valley on the southern edge of Prague (for additional details, see the next chapter). All are dated to the late phase of the Early phase of the Iron Age (Bylany culture, Ha C—D1, 800–550 B.C.) and to the transitional horizon between the Early and Late Iron Ages (Ha D—LT A).

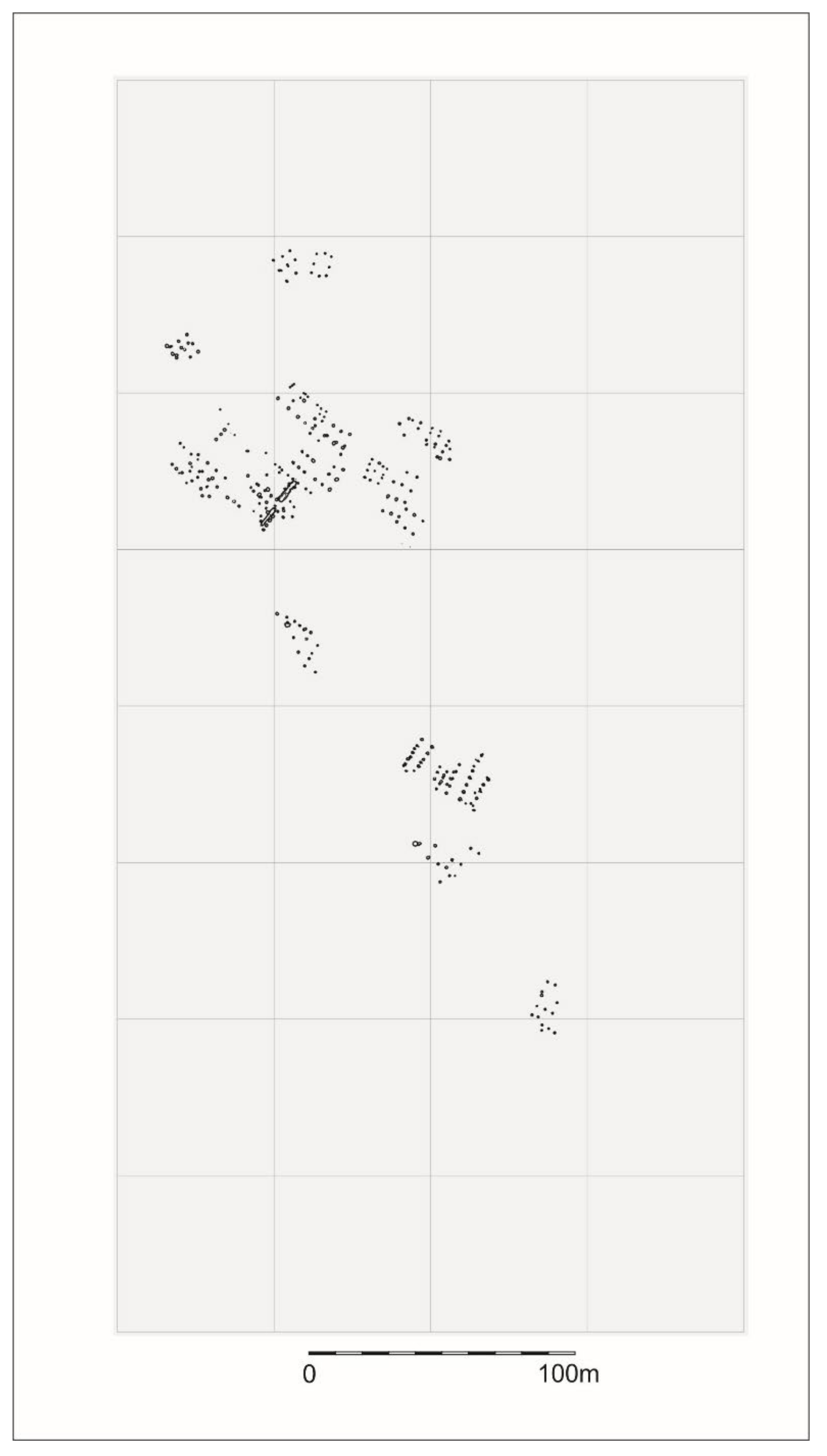

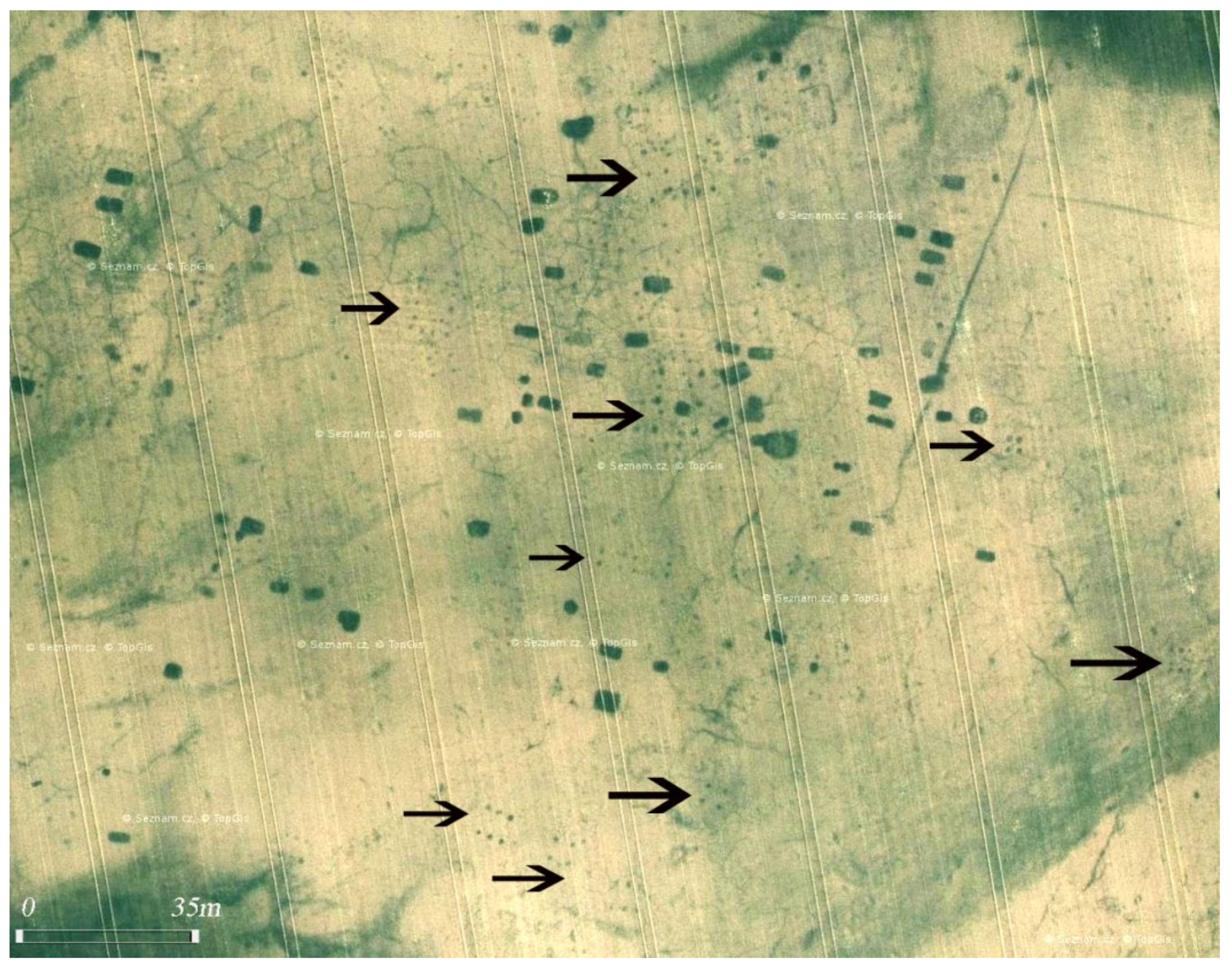

The site with the greatest concentration of recorded aboveground post structures detected by vegetation marks during a visual aerial survey is

Straškov (Litoměřice district). As it is clear from the overall plan of this area (

Figure 4A,B), in addition to the variants described above, the occurrence of other floor plans of aboveground structures is documented, in summary:

Variant 1—three rows of four posts enclosed by a trench with an entrance interruption on one of the shorter sides (

Figure 4);

Variant 2—three rows of three to five posts without an enclosure trench (

Figure 4A-2)

Variant 3—posts regularly arranged in rows, the layout of which creates a ground plan distinct from variants 1 and 2 (

Figure 4A-3)

Combination of variants 1 and 2—always one structure of the first variant and in its vicinity several (two or more) structures of the second variant—is safely documented at the sites investigated by excavation (see the following chapter), especially at the Kolín and Roudnice nad Labem sites (the latter is only 5.3 km due north of

Straškov, while Mt. Říp is equally distant from both areas—about 3.5 km). The occurrence of all three variants recorded at the Straškov site seems to confirm the former significance of this location within the settlement structure of the landscape under Mt. Říp in late prehistory. The validity of this opinion, specifically for the Late Iron Age, is supported by the presence of a large burial ground only about 1.5 km away, which has been documented by both excavations (before and after the Second World War [

16]) and aerial survey. In the immediate and more distant surroundings of the Straškov settlement, both types of research (in several cases their joint utilization [

17]) have documented a number of other manifestations of prehistoric and early medieval residential activities.

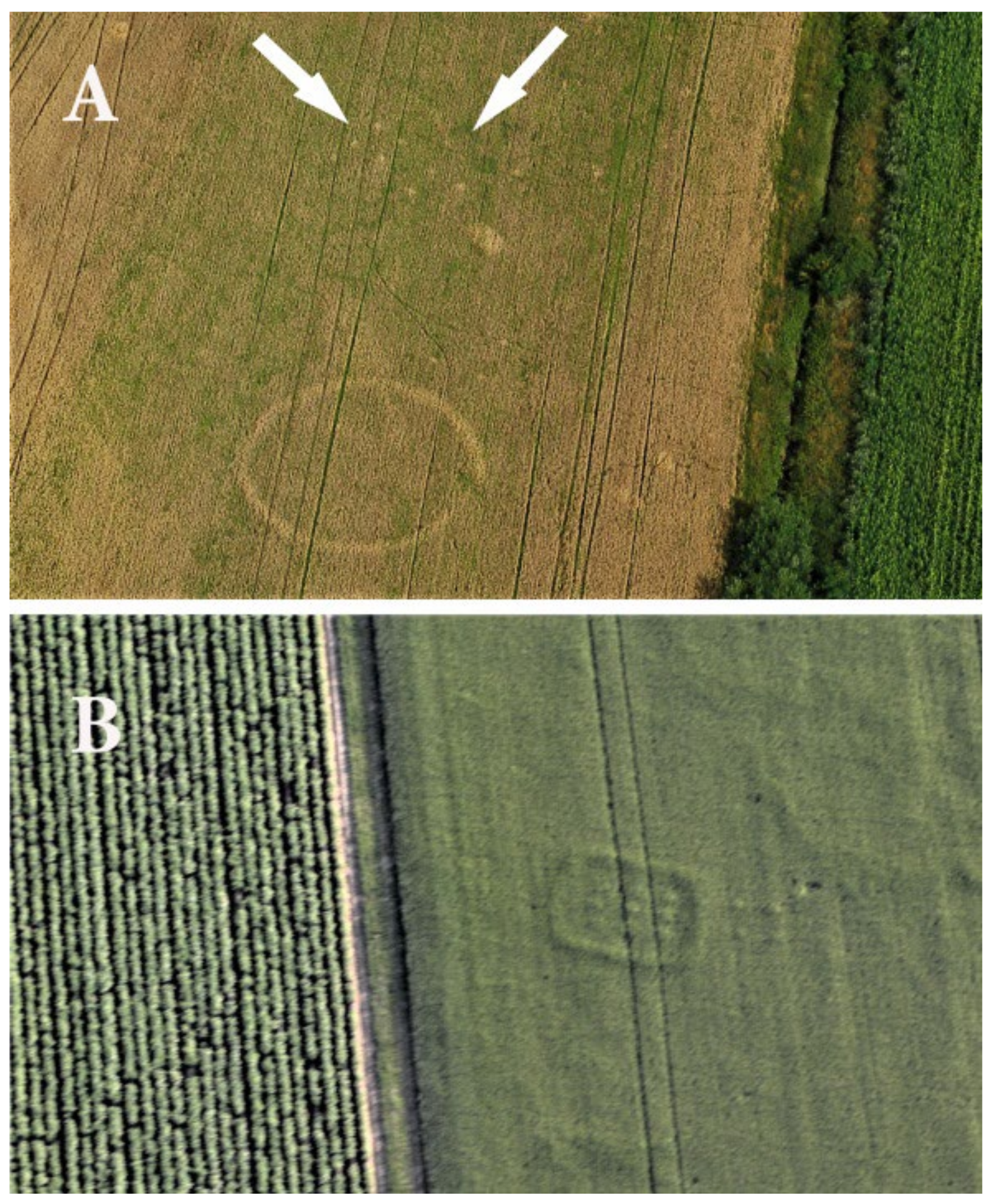

Figure 4.

Straškov—Early Iron Age (Bylany culture) site made visible by cropmarks on a barley field in mid-June; (A): aboveground structures (1,3), sunken house (4), and irregularly dispersed settlement pits (2); (B): the site as mapped in GIS ArcMap; (C): detail of the Straškov variant 1 structure; (D): Kolín: aerial photo of the structure A (see Figures 13 and 14B) during excavation (all aerial photographs in this paper were taken by M. Gojda. the permission of their reproduction was given by courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences).

Figure 4.

Straškov—Early Iron Age (Bylany culture) site made visible by cropmarks on a barley field in mid-June; (A): aboveground structures (1,3), sunken house (4), and irregularly dispersed settlement pits (2); (B): the site as mapped in GIS ArcMap; (C): detail of the Straškov variant 1 structure; (D): Kolín: aerial photo of the structure A (see Figures 13 and 14B) during excavation (all aerial photographs in this paper were taken by M. Gojda. the permission of their reproduction was given by courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences).

A characteristic element of the area in Straškov, as well as most other sites, is the presence of several sunken houses, irregularly scattered near all three variants of aboveground structures (

Figure 4A—marked 4). Other sites in the Mt. Říp region include:

Račiněves (Litoměřice district), one of the largest prehistoric settlements (c. 30 ha) discovered in Bohemia by vegetation marks detected during an aerial survey and also captured on orthophoto maps published on the website

www.mapy.cz (accessed on 18 January 2022). In addition to a large number of sunken houses and pits, several spot features—postholes—arranged in parallel rows and representing the floor plans of the third variant of aboveground structures are visible on the surface of this area (

Figure 5).

Rovné (Litoměřice district) is located in the immediate vicinity of Mt. Říp, on a distinctive flat elevation near its northern base. In addition to many pits and several sunken houses, aerial photographs of this settlement also show spatially arranged postholes creating a more or less regular floor plan of the defunct aboveground structure. Undoubtedly the most interesting feature is a rectangular enclosure (dimensions 12 × 9 m, width of the ditch/trench c. 1 m, rounded corners) with an entrance interruption on the south side, the ground plan of which is complemented by a group of large postholes (diameter 0.5–1 m) arranged in three rows. The longer axis of this likely single unit is perpendicular to the longer side of the enclosure, and approximately two-thirds of the ground plan of the feature is located inside the enclosure. Their spatial relationship clearly indicates that these are at least features whose existence was linked to one other or, even more likely, that they represent a single structural unit. It is not possible to rule out the possibility that both features ‘respect’ one another completely randomly (with each coming from a different period), though its probability is minimal (

Figure 6A,B). Field excavation would significantly help in the interpretation of this double feature. In any case, we can state that the actual enclosure (ditch/trench), including the entrance interruption, is formally nearly identical to the features detected during the aerial survey in Straškov and uncovered during the excavations near Roudnice n. L. and in Kolín.

In the Mělník district, two sites have been recorded so far with the occurrence of the categories of structures we examined, namely in

Zálezlice—the first ever settlement discovered in the late 1990s by aerial survey in Bohemia, with features of both variants of aboveground structures accompanied by sunken houses (

Figure 6C), and in

Lobkovice (

Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Crop-marked Early Iron post-built aboveground structures at Rovné (

A,

B), Kozárovice (

C), and Lobkovice (

D) in area 1 (see

Figure 3).

Figure 6.

Crop-marked Early Iron post-built aboveground structures at Rovné (

A,

B), Kozárovice (

C), and Lobkovice (

D) in area 1 (see

Figure 3).

The second area, where aerial survey revealed concentrations of sites with aboveground structures with regularly distributed postholes, is the central Elbe region in the Kolín, the eastern part of central Bohemia (

Figure 3, area 2). All of the previously discovered sites in this region documented by aerial photography are solitary features—postholes arranged in two or more rows forming an incomplete floor plan of structures with dimensions comparable to features recorded in the Mt. Říp and Mělník regions. Their functional interpretation and dating to the Late Hallstatt period are therefore highly uncertain. These are the sites of

Cerhýnky (

Figure 7A),

Ovčáry and

Chotutice.

It is interesting to note that vegetation marks above the features of the modified variant Straškov 1 (floor plan 3 × 3, absence of entry interruption in the perimeter trench, smaller size) were also detected during 2020 aerial survey by M. Gojda in southern Moravia (eastern part of the Czech Republic) in Pasohlávky (

Figure 7B).

2.3. Aboveground Structures Dated by Field Excavations in Bohemia

The features presented in this part of the paper, all of which were investigated during rescue archaeological excavations, provided very important data for the knowledge of floor plan construction details and chronology, which confirms the assumption of their dating to the Early Iron Age.

A post-construction with an oval palisade enclosure discovered in Prague-Miškovice (

Figure 8, indicated by the upper placed red arrow) was part of a Bylany culture settlement, where there were also at least thirteen other post-built structures, thirteen sunken houses, ten pits and five clay pits [

18] (see page 697), [

19]. The main structure at this settlement differed somewhat in terms of floor plan from most of the structures discussed in this work. Its palisade trench was not in the shape of a rectangle with rounded corners but in an ellipse. There were nine posts in three rows slightly outside its center, and a group of regularly spaced postholes situated east of the palisade trench ([

19] see Figure 19). The palisade was interrupted on its northern side for the entrance to the area. Possible interpretations of the construction include cult functions, an assembly space for the council of elders, a granary, and a ‘house of the dead’ [

19] (see page 267). However, these possibilities are mere conjecture at this point, as none of them can be either confirmed or refuted.

In terms of floor plan characteristics of the features studied in this paper, feature no. 1048 at the settlement in Prague-Miškovice seems to be a far more suitable candidate (

Figure 8, indicated by the lower placed red arrow) ([

19], see Figure 13). The floor plan of the palisade trench of this feature corresponds much more closely to the form characteristic of the investigated features. However, we do not find any traces of a post-construction on the inner surface of feature no. 1048. Nevertheless, this need not be a complete obstacle since even with the features of this type described below, we often observe the absence of postholes, which have not been preserved due to their shallow depth. Moreover, feature no. 1048 in Prague-Miškovice was not fully investigated, as part of it lay outside the excavated area.

Another site where we encounter features of the studied type is the Hallstatt settlement in Čestlice [

20]. Some finds from this settlement could be dated to the Bylany culture period (Ha C—D1, 800–550 B.C.), others only in general to the Early Iron Age. On the other hand, other earlier or later artifacts were not found at the site, so the mentioned age can perhaps also be applied to one type of feature identified here in two construction phases (

Figure 9): a trench with a rectangular ground plan with rounded corners, the internal surface of which has postholes in a regular configuration ([

20], see Figure 5).

Regarding the reconstruction of the appearance of the described structures, the structure from the Prague-Miškovice settlement was interpreted as a post-built house surrounded by an elliptical palisade [

19] (see pages 266–267). As such, the palisade and the post-built structure formed two structurally unconnected units between which free movement was possible. The feature in the settlement in Čestlice can perhaps be reconstructed as a post-built house surrounded by a palisade of a rectangular floor plan with rounded corners. However, we are not able to discern from the archaeological context whether it was a structure with a post-built construction, the outer walls of which are formed by a palisade, or whether it is a free-standing post structure with a daub outer wall that is surrounded by a palisade fence. While it cannot be ruled out that the described structures were dwellings or small farmsteads, this interpretation seems less likely in light of some specific findings. The surface with postholes, which we regard as relics of a structure, is relatively large in relation to the area defined by trenches. If these structures were dwellings, the lack of free space between the walls and the fence would certainly complicate many of the activities associated with the settlement, as well as movement around the structure itself. Based on the above facts, it is possible to consider a different function for both structures, e.g., one involving their economic use. Evidence of any workshop activities, such as the processing of metal or other raw materials, was not observed at the site. As such, animal pens or granaries can be considered. The protection of stored material (crops) or farm animals would also correspond to the presence of a fence as a barrier preventing, for example, pests from entering the structure, etc. In this respect, it is interesting that a post-built structure of a similar character uncovered in the Bylany culture residential area in Prague-Miškovice ([

21], see annex 2) was also interpreted as a granary. Thus, although the presented interpretation of the feature does not seem unlikely, it is clear that another role or even a combined use of these structures also cannot be ruled out completely. In this sense, it is possible to recall interpretation variants for a similar feature in Prague-Miškovice [

20] (see page 267).

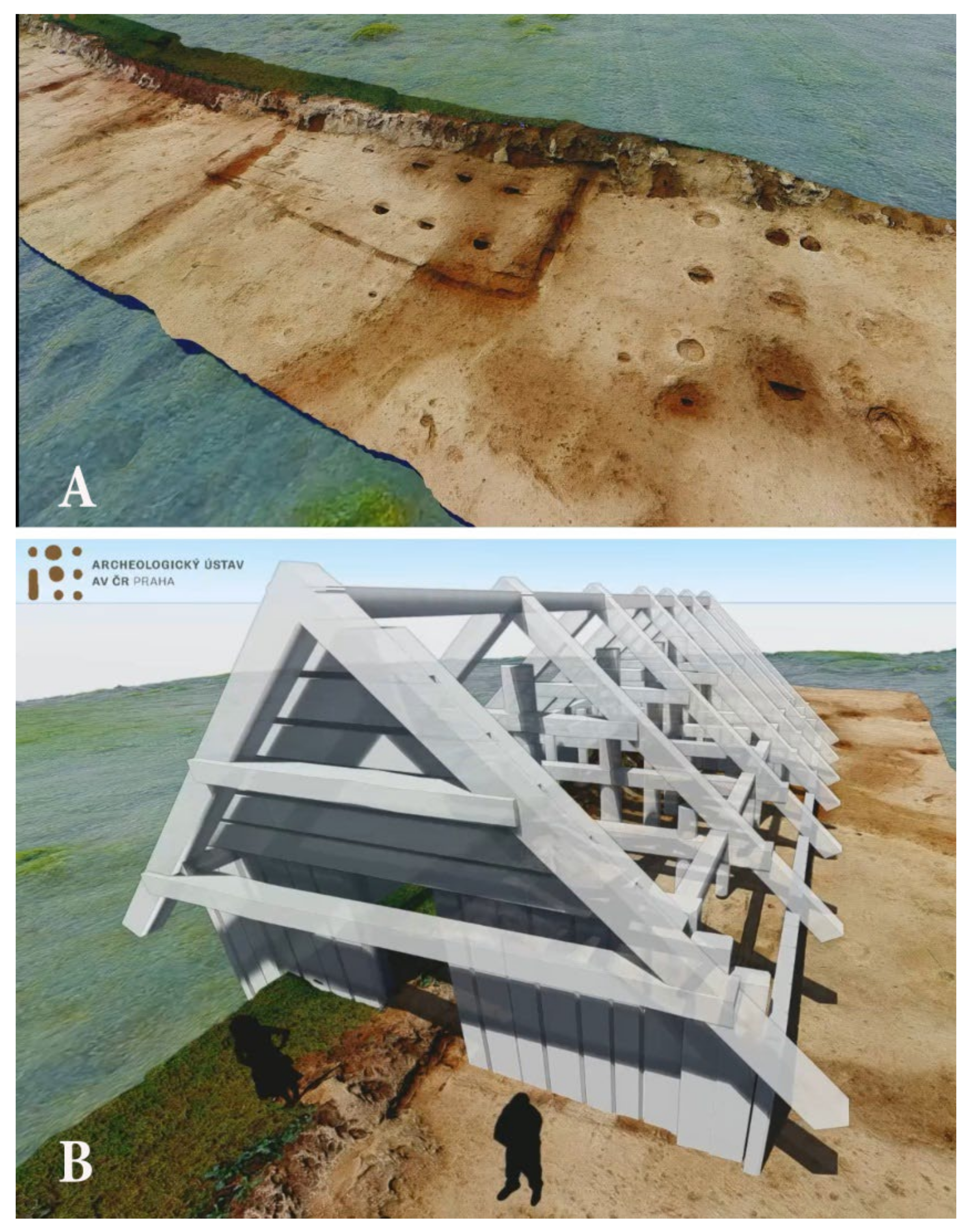

The latest archaeological discovery of an aboveground structure of the described structure occurred in 2019 during an archaeological rescue excavation of the Roudnice nad Labem bypass (unpublished). The structure was part of a Bylany culture settlement (

Figure 10). A rectangular palisade trench with rounded corners formed its perimeter, and the demarcated surface had two rows of three posts (

Figure 11). In the north-western part of the feature, these two rows were followed by four postholes. Unfortunately, the entire floor plan of the structure could not be uncovered, as part of it was already outside the excavated area. As a result, we do not know if there were one or more longitudinal rows of posts on the inner surface, though it is probable. Again, no conclusive archaeological finds were made directly in the palisade trench of this structure or in its postholes. However, there were settlement features in its immediate vicinity for which the said cultural affiliation could be proven. Moreover, no later features were found in the area.

Interesting data come from the assessment of the spatial relationships of structures with palisade enclosures within individual settlements. As already indicated above, these structures at Hallstatt settlements appear very often near post-built structures with a regular arrangement of posts, so that one structure with a palisade fence is always accompanied by several post-built structures without a fence. In Prague-Miškovice, these are features MIS 1 and MIS 9 ([

19], see Figures 2 and 8, post-built structures with a rectangular floor plan, with the main load-bearing posts in a 3 × 3 configuration.

Figure 11.

3D model of the Roudnice nad Labem site in the final period of its excavation (A), and 3D reconstruction of the probable appearance of the structure surrounded by a linear trench (B)—in this case, interpreted as a base for its wooden perimeter wall (author: J. Unger, the permission of reproduction of this figure was given by courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences).

Figure 11.

3D model of the Roudnice nad Labem site in the final period of its excavation (A), and 3D reconstruction of the probable appearance of the structure surrounded by a linear trench (B)—in this case, interpreted as a base for its wooden perimeter wall (author: J. Unger, the permission of reproduction of this figure was given by courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences).

The situation is similar in the case of a Čestlice feature captured in two phases. The Čestlice settlement is part of an agglomeration of five settlements (Prague-Křeslice, two settlements in the cadastre of Prague-Pitkovice, Prague-Benice and Čestlice) dating to Ha C—LTA ([

22], see Figures 1 and 2). It cannot be ruled out that all five settlements covering an area with a length of roughly 3 km may belong to one larger Early Iron Age agglomeration. The Čestlice site, where we record the aforementioned feature with a palisade enclosure found in two construction phases, is only tens to hundreds of meters away from the settlement in Prague-Benice. It is at this Hallstatt period settlement that we also record several post-built structures (

Figure 12) with regularly arranged load-bearing posts in two or three rows ([

23], see Figure 4).

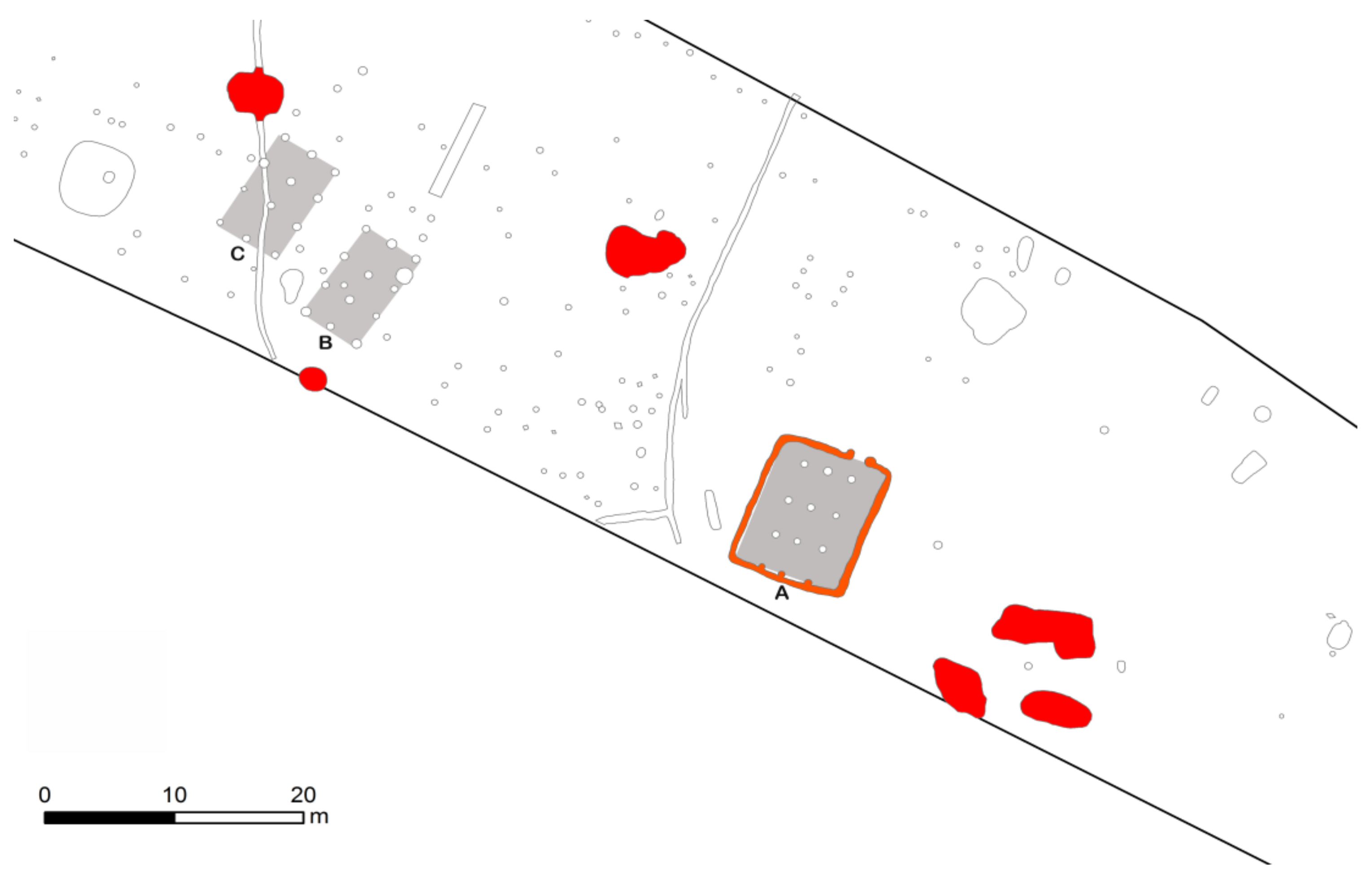

The situation around the structure with a palisade enclosure in Roudnice nad Labem is quite characteristic. In its immediate vicinity are four aboveground features with a rectangular floor plan formed by regularly spaced posts in several rows. The structure adjacent to the feature with a palisade enclosure from the southeast side has a supporting system consisting of main posts in a 3 × 3 configuration. Another feature, located at a greater distance and also to the southeast, has two clearly visible rows of postholes, but it cannot be ruled out that it was originally a 3 × 3 configuration, with one row of posts not having been preserved. The basic 3 × 3 configuration may also have been used for two features northwest of the feature with a palisade trench. Here, however, this configuration was supplemented by additional posts, which could represent extensions of the basic floor plan of the structure (

Figure 10).

Figure 12.

Posthole houses in the settlement from the Early Iron Age in Prague-Benice (according to Trefný—Polišenský ([

23], Figure 4)).

Figure 12.

Posthole houses in the settlement from the Early Iron Age in Prague-Benice (according to Trefný—Polišenský ([

23], Figure 4)).

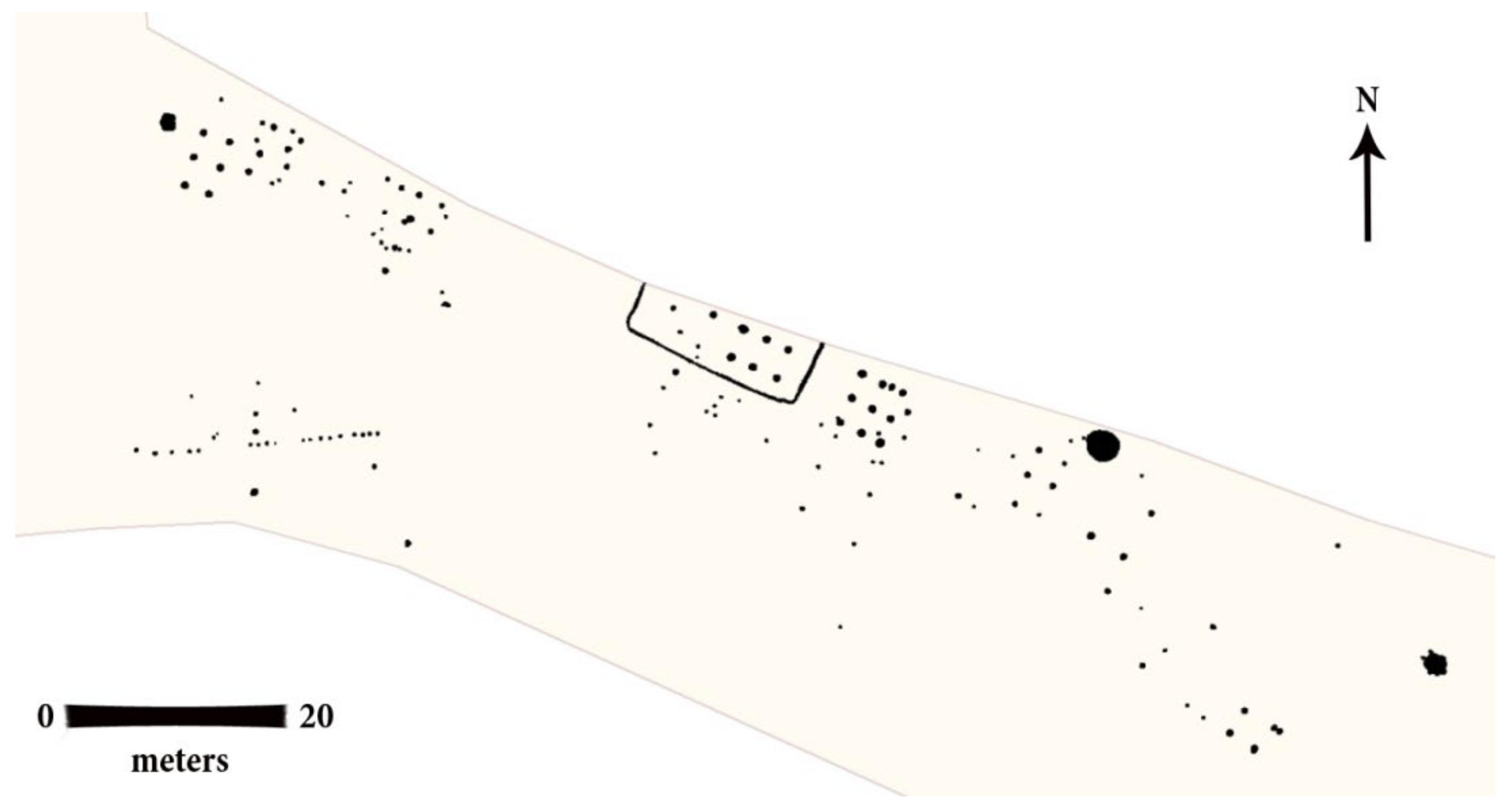

The excavation in Roudnice nad Labem captured only a peripheral part of the Bylany settlement, which probably stretched further northward. However, even this outer part of the settlement provides some indications of regularly arranged development. All five described features are situated in a single line, and the axes of all four post-built structures are oriented in the NW-SE and SW-NE direction. The longitudinal and transverse axis of the structure with the palisade enclosure is oriented in the same direction. The orientation of the axes of these structures was therefore chosen with regard to other structures in this settlement based on a unified system. In this sense, we can only regret that the excavation did not capture other parts of this settlement so that we could either confirm or refute the suggestion of a certain floor plan.

In summary, structures with a palisade enclosure/palisade perimeter wall studied during the last two decades in Prague-Miškovice, Čestlice and Roudnice nad Labem represent an important form of Hallstatt settlement architecture appearing in the environment of significant settlements of supraregional importance with evidence of long-distance contacts or more complex settlement forms, including the center (refuge) and the adjacent external settlement. The fact that we are still unable to advance the interpretation of these structures from the level of hypothesis to more specific conclusions does not diminish its significance in any way. On the contrary, it emphasizes the need for further research using interdisciplinary analytical methods, which can bring us significantly closer to a final interpretation.

Rescue archaeological excavations conducted in the years 2008–2010 in connection with the construction of a road bypass for the central Bohemian town of Kolín produced a great deal of evidence of the settlement of the landscape in its vicinity in late prehistory. The Early Iron Age settlement component was located at the edge of the terrace above the Polepka River (sector VI of the archaeologically investigated area,

Figure 13); the investigated features were situated no more than 100 m from the south-facing edge of the slope above the river floodplain, though some features are also situated on the slope and almost in the river floodplain [

24].

Across the hidden area, two apparently concentric (slightly curved) palisade trenches ran with a distance of 34–43 m between them; they were captured in lengths of 40.8 m and 44.3 m. The inner palisade was evidently also repaired and provided with a partition. The walls of the trenches were angled, the bottom was flat, and the depth in places was up to 50 cm (

Figure 14A). Inside the enclosed area, less than 5 m from the inner palisade, stood a large post-built structure with a perimeter trench (structure A,

Figure 14B). Nearby, at a distance of 10 m, a concentration of large clay pits with Bylany culture material was recorded. In the space between the palisades, a post-built structure without a perimeter trench (structure B) and a number of smaller structures with a post-construction were captured; another large feature with a post-built construction (structure C) was identified in superposition with the outer palisade. One large settlement pit with Bylany culture pottery was captured in superposition with this palisade, and another pit and a storage pit were in the space between the palisades. The palisade trenches themselves did not contain any dating material, and their connection with the Hallstatt settlement is rather hypothetical. However, there is no other settlement component in the mentioned area for which an enclosure could be assumed. A multi-phase settlement should be considered for the Hallstatt farmstead.

Structure A: a rectangular feature with a post-construction and a perimeter trench, a length of 12 m, and a width of 9.4 m. The northern wall has a slightly asymmetrically placed entrance with a width of 0.94 m; the trench at the entrance ends with postholes that extend slightly outwards. The trench width is c. 0.5 m, depth 0.26 m, with smooth angled walls, flat to concave bottom and fill mostly dark brown. The internal structure consists of three rows of four postholes, the rear (southern) row in contact with the perimeter trench spacing between rows 1.6–19 m, spacing between three posts 2.8–3.2 m, spacing of rows from the perimeter trench 2.4–2.6 m. Dimensions of the internal structure without the perimeter trench are 9.7 × 4.4 m (

Figure 14B).

Structure B: a rectangular feature with a post-construction, length 890 cm, width 520 cm, structure composed of three rows of four postholes; spacing between rows 230–240 cm, spacing between the three posts 2.6–2.9 m (

Figure 14A).

Structure C: a rectangular feature with a post-construction, length 9.1 m, width 5.5 m, structure composed of three rows of four postholes. Spacing between rows 2.4–2.6 cm, spacing between the three posts 270–300 cm (the outer floor plan dimension of the features is stated at the level of the excavated surface and their depth is measured from this point; the excavated level in this space was 30 cm beneath the surface of the topsoil (

Figure 14A).

It is clear from the above data that structures B and C have the same construction and dimensions as structure A; only the peripheral trench is missing. Other structures are rather hypothetical and indicate the existence of smaller, perhaps economic, post-built structures, especially in the space between the palisade trenches. Several charcoals were analyzed from the fill of the perimeter trench of structure A, all from oak (identified by P. Kočár), and a larger number of charcoals from oak wood were also captured in the fill of features near the palisade, so it is possible that oak wood was used both for the enclosure and the walls of structures.

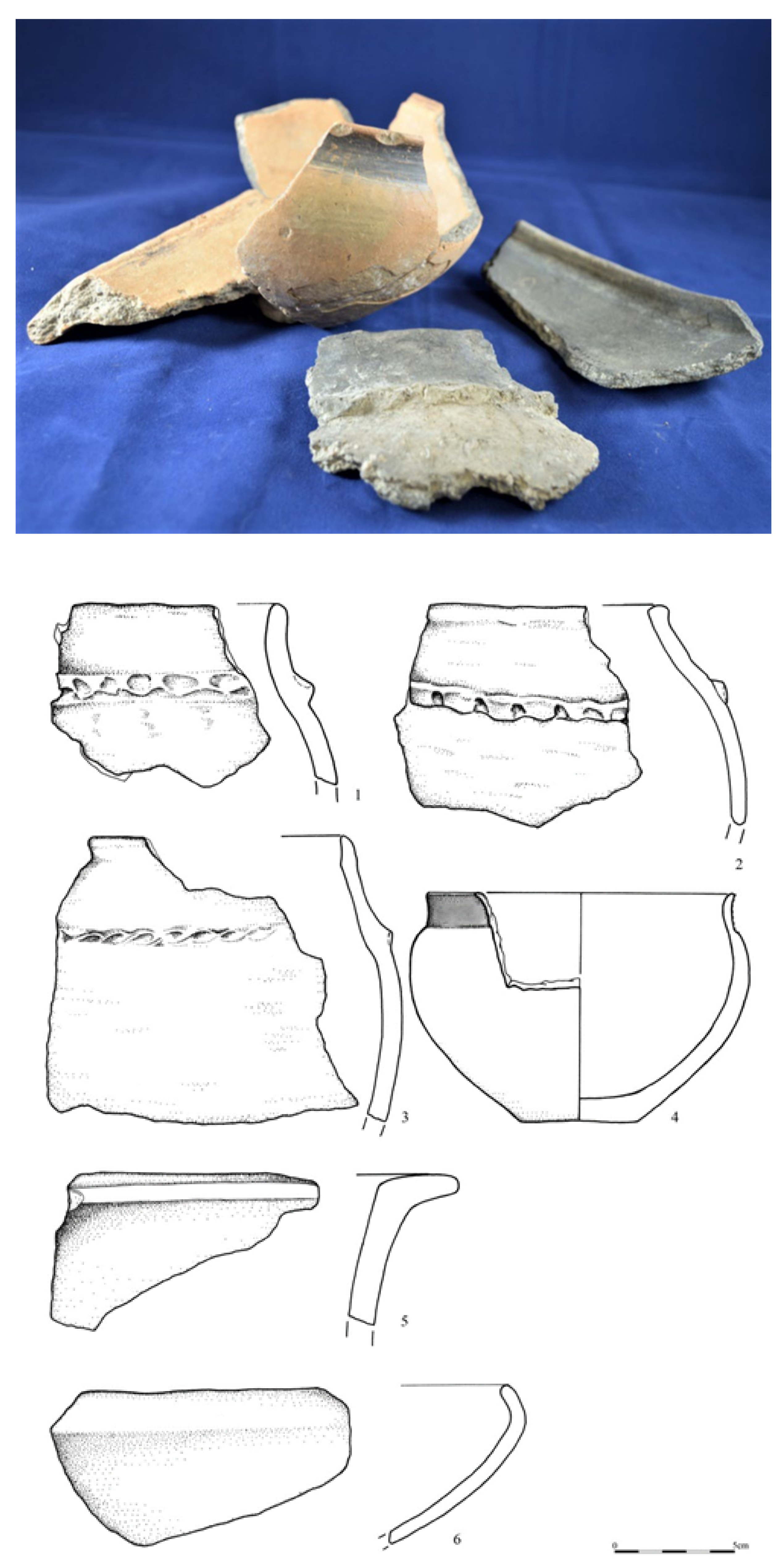

Large features captured near post-built structures can be assigned to the Bylany culture (800–550 B.C.) based on the ceramic material in the fill. They belonged mainly to common settlement pits; in one case, we can talk about a storage pit. Another storage pit was part of a larger group of pits, which, according to the dimensions, orientation and profile, could perhaps be regarded as a sunken house. Clay pits and pits with a fireplace in a niche in the wall and other unspecified pits were also uncovered. A preliminary analysis of the ceramic material makes it possible to assign the settlement to the middle to the late phase of this culture; finds that would clearly indicate the use of the site even in the Late Hallstatt period of Ha D2—LTA is still missing. The most common forms here are various types of pots, bowls, amphorae, cups, and fine ceramics with polished or painted decoration are also represented. There are also ceramic discs, various spindle whorls and bobbins, spoon handles, and in one case, a clay model of a wheel with spokes. For now, it is not possible to distinguish the developmental stages of culture in the ceramic material, the representation of which is shown by the horizontal stratigraphy of the site.

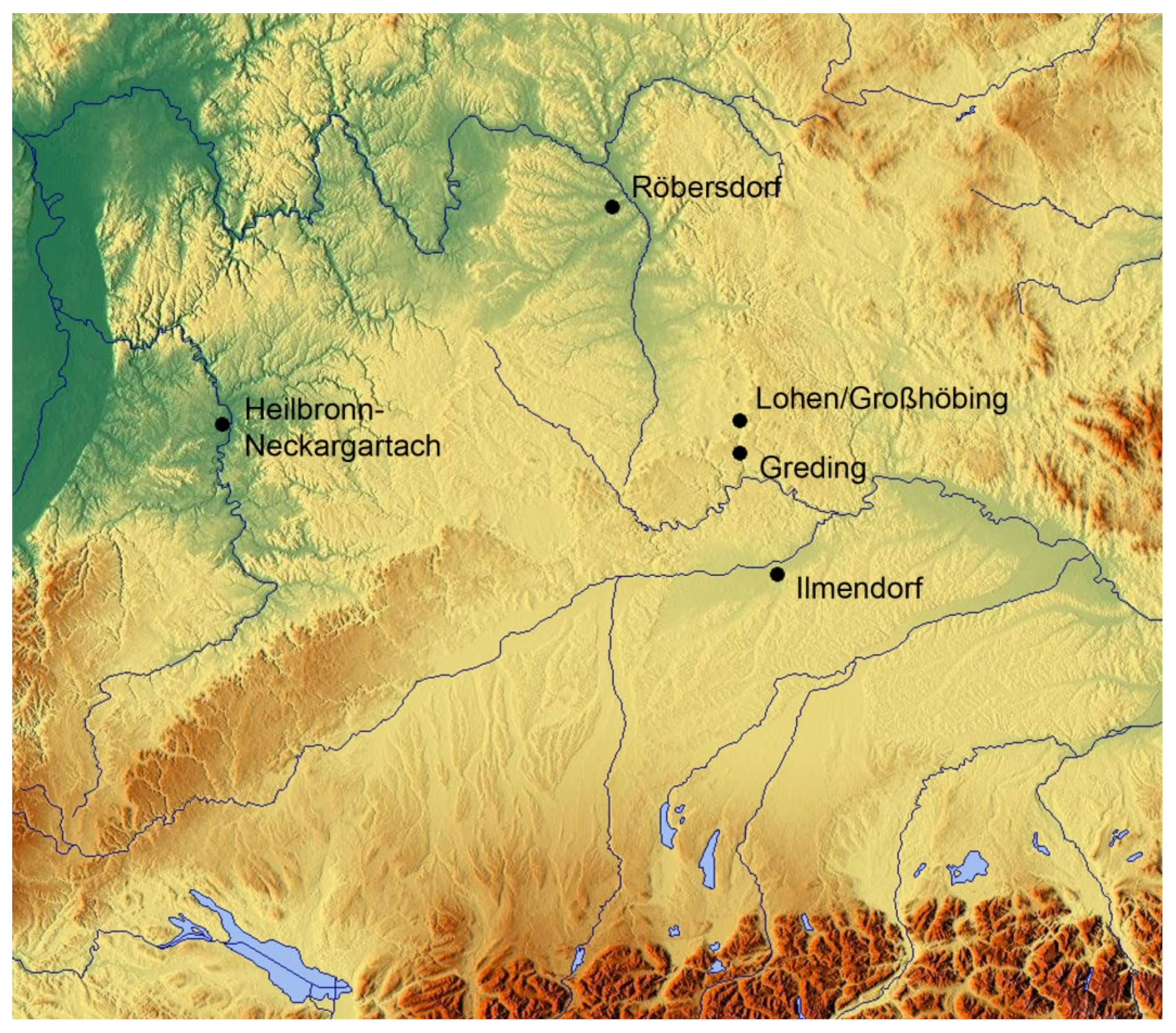

2.4. Post-Built Aboveground Structures Enclosed by a Perimeter Trench—The Southern German Perspective

Despite a remarkable number of large-scale excavations during the last two decades, individually trench-enclosed structures with large postholes indicating an aboveground floor construction still remain quite rare in southern Germany. The responsibility for this situation does not lie solely with modern agriculture, which would have led to the faster loss of the mostly shallower trenches because, in other periods, they are quite common. All examples have been documented only by means of excavations, while evidence from aerial photography is still missing. The geographical distribution of the few well-known structures of this kind suggests a cultural background (

Figure 15). All examples dating to the Early Iron Age come from the northeast of Bavaria, where relationships with the “Osthallstattkreis,” especially Bohemia and Moravia, were maintained. There, this type of construction has been documented more often. Apparently, these contacts did not remain on a superficial level but were even somewhat strengthened in some aspects. This is suggested, for example, by distinctive features of cult and by expressions of art, which have close parallels in Moravia.

The design of the individually enclosed structure occurs almost without an immediate precursor during the Hallstatt period. There is only one representative from Ilmendorf in Upper Bavaria, which, due to its surrounding structures, likely belongs to the Middle Bronze Age, even if it cannot be dated by artifacts [

25]. It consists of a circular trench of 5.2 to 5.5 m in diameter, which had a 1.27 m wide opening facing south. The trench was 54–78 cm wide and dug relatively close to a 2.2 m square layout with four posts. An asymmetrically placed fifth post is interpreted as a repair, the feature itself as the supporting structure for a roof or a raised platform. It differs slightly from the actual type, and as there were both clear settlement structures and other empty circular trenches and even grave mounds in the close vicinity, its interpretation is uncertain. Even if it were a storage structure with a raised floor, it hardly would have established a tradition. No links to the Hallstatt period can be identified, so even in its time, it would quite likely have been regarded as a special form.

Figure 15.

Distribution of the sites in southern Germany is mentioned in the text.

Figure 15.

Distribution of the sites in southern Germany is mentioned in the text.

Between the modern villages of Lohen and Grosshöbing in Central Franconia, a small settlement, presumably consisting of just a few farmsteads, was investigated during a rescue excavation in the year 2000 [

26] (see pages 100–101). Due to erosion damage, the find conditions were not good (

Figure 16A). However, several layout plans of posthole structures were revealed completely or partially and showed, in general, a north-south orientation. A probably square trench with rounded corners measuring 18 × 18.5 m was a complementary structure. While its northern part was largely missing and therefore can only be reconstructed schematically with an area of 333 m

2, its southern section ended to the east by connecting to a small six-post construction of 4 × 6.7 m. In the western half, the 30–50 cm wide trench had several narrow gaps, of which only a 1.6 m wide opening in the southwest corner can be safely interpreted as an entranceway. In this western half of the group, one more six-post construction was placed together with only a few more finds. Although the number of finds was not particularly high and metal objects were completely missing, the ceramic fragments—of which some came from the postholes—cover a spectrum typical for a rural settlement of the (Late) Hallstatt period.

Several campaigns in the period between 1995 and 2006 saw the excavation of a 1.6-hectare settlement area on the outskirts of the nearby town of Greding. This site was occupied between the Late Neolithic and the Hallstatt period, while the Early La Tène period left no traces [

25] (see pages 90–92). Only parts of the structures have been analyzed to date so that only individual find complexes and certain areas of the settlement can be addressed chronologically. However, in the area not yet analyzed, there is an oval trench without openings measuring about 15 × 21 m (

Figure 16B). While most of the included postholes appear to belong to different settlement phases, and no systematic arrangement can be recognized among them, the trench seems to surround an 11 × 6 m six-post construction, which is also characterized by larger posts. With its alignment from northwest to southeast, the construction follows the preferred orientation determined for the Late Urnfield and Hallstatt periods. More specifically, the group cannot be dated for the time being.

Due to several overlaying settlement phases and subsequent disturbances, a find near Röbersdorf in the Bamberg district is different in a similar way [

27]. There, a trench measuring 11.6 × 12.6 m with rounded corners and several disturbances on the south side was found (

Figure 16D). In the northwest of the 30 cm wide trench, a 1.8 m wide opening was recognizable and flanked on each side by a posthole. Furthermore, postholes were found in the trench itself at regular intervals. The included area was around 140 m

2 and contained further trench portions, pits as well as a number of postholes. Five of them complimented each other exactly in the center of the trench structure to a—unfortunately disturbed—rectangular post-construction of about 3.5 × 5 m. Due to the low sensitivity of settlement pottery to precise dating, the complex cannot be dated more accurately than to the Hallstatt period in general. However, other finds from the immediate surrounding are certainly slightly younger and already belong to the transitional horizon between the Late Hallstatt and Early La Tène periods.

Since the interpretation of these finds cannot be solved satisfactorily based on finds (artifacts), various observations on the settlement system of the Early Iron Age in the relevant region can contribute. Therefore, it should be noted that storage pits and silos of a cylindrical or conical shape were quite rare before the Early La Tène period [

25] (see pages 103–104). A fair reason could have been a change in climatic conditions, which also affected soil hydrology. B. Sicherl stressed the link between the occurrence of conical storage pits and climatically favored phases, with higher crop yields, population growth and the prerequisite for ground storage as decisive factors [

28]. His observation that in Bavaria after LT A, conical storage pits were no longer used cannot only be confirmed but also supplemented by the fact that they—at least in the northern parts of the country—first came into use with the beginning of the Hallstatt period and had their climax in LT A [

29] (see page 165). Their occurrence is recognizably framed by the two sudden climate changes around 800 and 400 B.C. and seems to be coupled in its intensity reciprocally at the course of the climate curve.

Without silo and storage pits, the problem of keeping stocks of cereal reserves must therefore have been solved in another way. Here, the small six-post structures gain meaning because, with some likelihood, they can be interpreted as raised floor structures [

26] (see pages 97–98). In addition to the comparatively small usable area, the commonly observed concentration in certain settlement areas speaks for this interpretation. Of course, the 66 m

2 structure of Greding is far from ordinary in this respect. Incidentally, it should be mentioned that this also means a modified economy because, for long-term storage on or above ground level, additional preparation measures such as the drying of crops are required [

26] (see page 104). In southern Germany, six-post structures of the presented squat-rectangular type were built since the Late Bronze Age and the Urnfield period and remained a common type in the following periods of prehistory [

30] (see page 103), [

26] (see page 97). Together with four-post structures, in the Final Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, they were by far the most common form of structure [

26] (see page 104), though not only because they can be detected easier as more complex structures in the tangle of the excavation plans. In the discussed region, the six-post structure seems to appear even more frequently than the four-post edifices that were typical for the La Tène period [

26] (see page 97).

Figure 16.

(

A)—Lohen/Grosshöbing. Detail of the site plan showing the two structures with the remainders of the perimeter ditch. After: ([

26], see plate 197); (

B)—Greding, detail from the site plan showing the six-post structure with its oval-shaped perimeter ditch. After ([

26], see Beil/supplement 13); (

C)—Heilbronn -Neckargartach. Plan of the Late La Tène site. After: ([

31], see Figure 62); (

D)—Röbersdorf. Detail from the site plan showing the perimeter ditch and linked structures in their chronological context. After: ([

27], see Figure 97).

Figure 16.

(

A)—Lohen/Grosshöbing. Detail of the site plan showing the two structures with the remainders of the perimeter ditch. After: ([

26], see plate 197); (

B)—Greding, detail from the site plan showing the six-post structure with its oval-shaped perimeter ditch. After ([

26], see Beil/supplement 13); (

C)—Heilbronn -Neckargartach. Plan of the Late La Tène site. After: ([

31], see Figure 62); (

D)—Röbersdorf. Detail from the site plan showing the perimeter ditch and linked structures in their chronological context. After: ([

27], see Figure 97).

During the La Tène period, this distinctive and rare design no longer appeared in southern Germany. Perhaps its idea was caught one last time when a singular find complex was unearthed in 1993 at Heilbronn-Neckargartach [

31]. In the center of an approximately 33 m wide and not very accurate circular ditch, a structure of nine posts and dimensions of 6 × 7 m and another with four posts and dimensions of 2.5 × 2.5 m was found (

Figure 16C). The circular ditch had a 3 m wide opening to the northeast, which was flanked by four posts, probably belonging to a small gatehouse structure. Although not a single find could be obtained from these structures, ceramics from a nearby pit help interpret the complex as a small rural homestead of the Late La Tène period.

However, the mostly square or squat rectangular four-post structures with a surrounding trench, which were presented for the first time in more detail as a structure type in the ‘Viereckeschanze’ of Bopfingen-Flochberg [

32] (see pages 103–112) and since then have been relatively numerous in Late La Tène-related contexts, certainly have nothing in common with them. Their trenches only served to accommodate the structure’s wall.