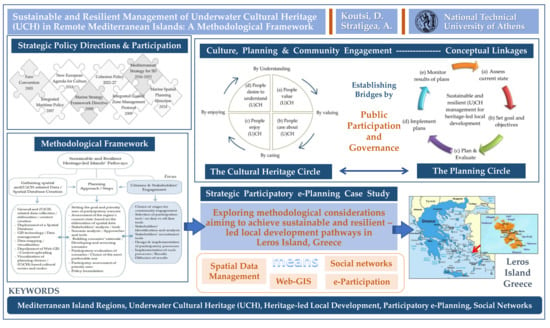

Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Ensure sustainable local development by safeguarding tangible and intangible, assets and supporting equitable local tourism trails [12];

- Broaden resilience of local destinations to external crises;

- Feature sustainable tourism patterns by promoting environmentally-, culturally-, and socially-responsible decision-making [13], thus spreading positive impulses to local employment and income; and, most importantly

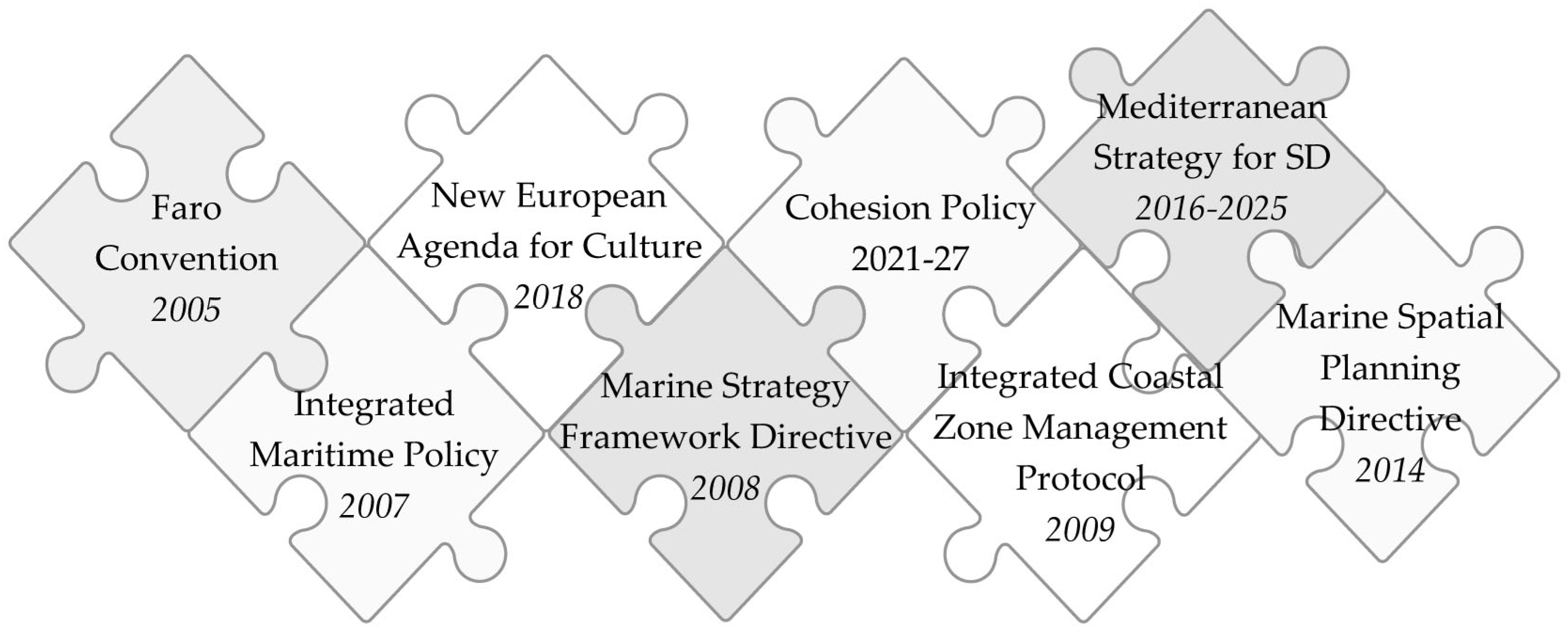

2. Setting the Scene for Stakeholders’ Engagement in (U)CH Management—The Policy Context

- Gathering multi-level, multi-objective, and multi-stakeholders’ information;

- Placing this information within the frame and priorities of the international, European, national, and regional or local level; and

- Making well-documented decisions that are grounded on the aforementioned information and are framed by relevant policy directions and constraints.

2.1. The International Context

2.2. The European Context

2.3. The Regional—Mediterranean—Context

2.4. Key Conclusions

3. Sharing the Power—Participatory Planning in Sustainable (U)CH Management

3.1. Public Participation in (U)CH Management

- Complex nature of sustainability, calling for multi- and inter-disciplinary approaches and cross-fertilization of distributed, to a variety of societal actors, knowledge;

- Necessity to collaboratively visioning and reach consensus towards a desired future;

- Need for integrated approaches to sustainability, embedding or seeking to compromise diversifying stakes or interests;

- Evolving governance schemes, unfolding at multiple levels, both horizontally and vertically.

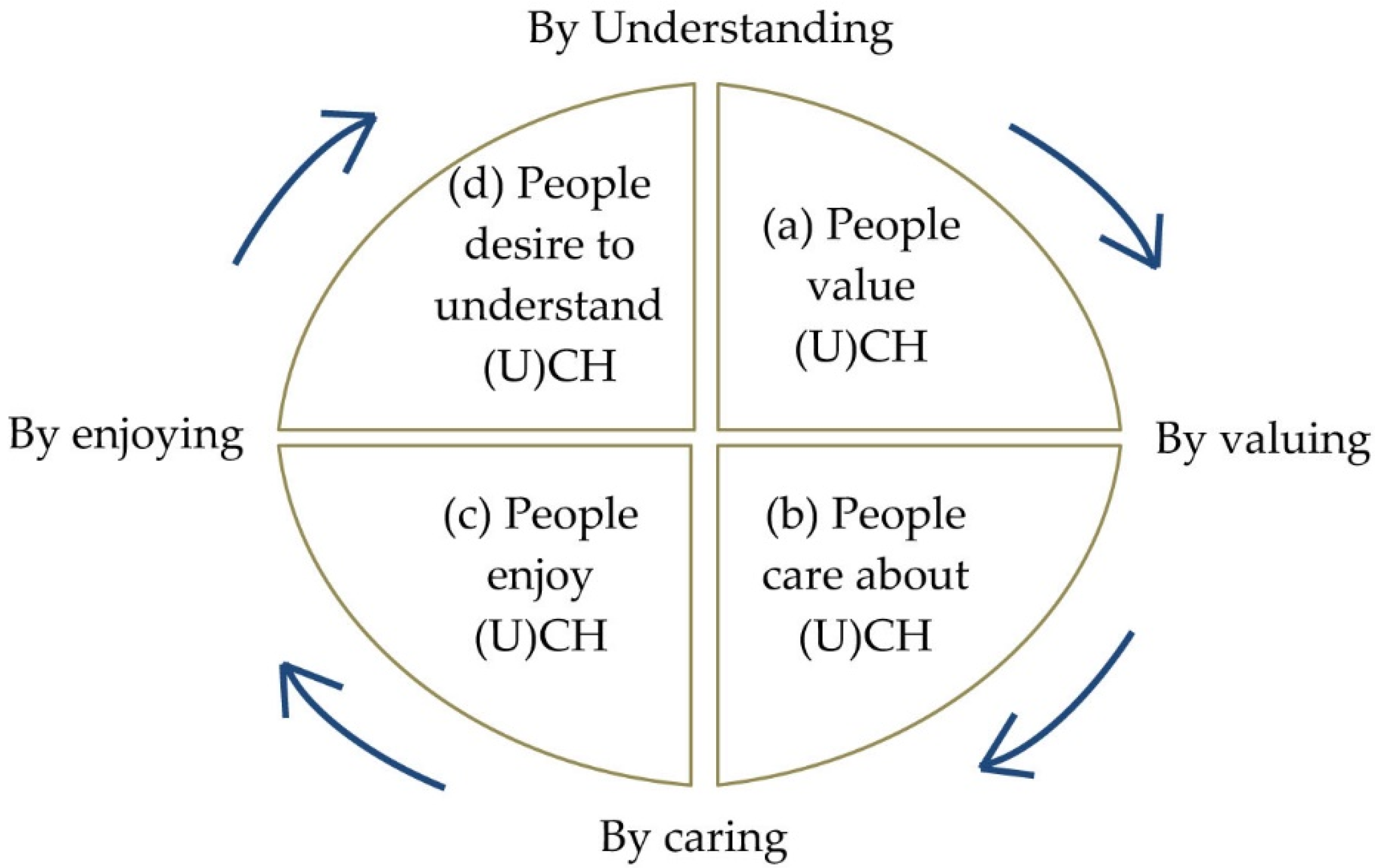

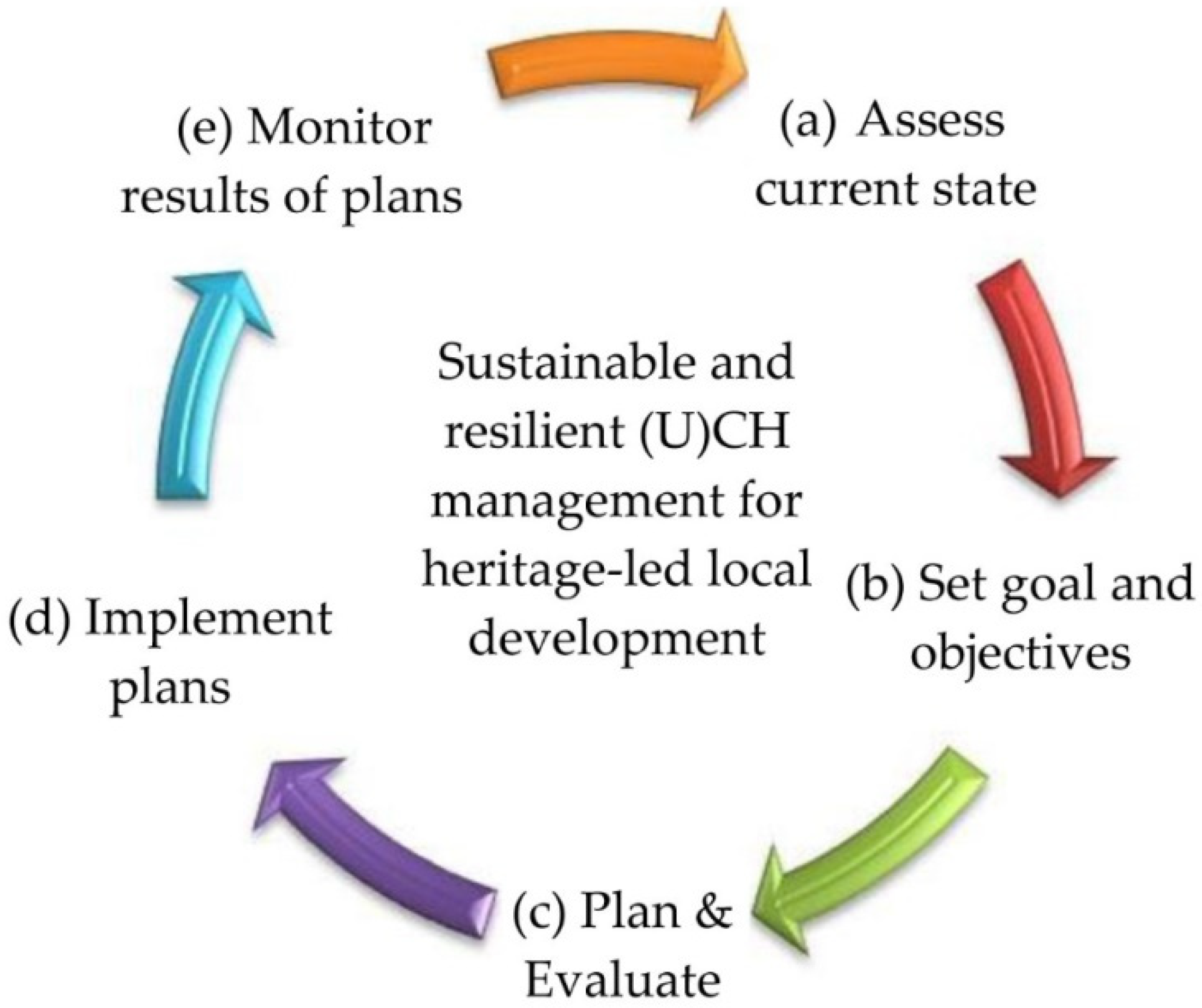

3.2. The Triptych of Participation, Cultural Heritage Cycle and Planning Cycle

- Promote models for UCH management that can support sustainable economic development objectives of regions, implying thus the sustainable and resilient exploitation of this heritage for steering growth and jobs’ creation in respective territories; and

- Increase the positive image of underwater archaeology and strengthen the involvement of the public in the awareness, protection, and enjoyment gained out of UCH.

- (a)

- ‘Assess current stage’: at this stage the role of participation is threefold, addressing community engagement as a means for: (i) collecting (U)CH tangible and intangible information that can help planners to better grasp the scenery, the type or location of (U)CH and its surrounding environment; (ii) identifying values attached to (U)CH, intriguing community actors to consider their personal linkages to (U)CH and valuing this heritage; and (iii) establishing a platform for interaction, to be held throughout the planning exercise and play a catalytic role for raising community awareness and supporting the creation of community networks. Within this stage, actors and stakeholders engaged establish linkages with (a) and (b) stages of the cultural heritage cycle (Figure 3).

- (b)

- ‘Set goal and objectives’: at this stage, community engagement is crucial for scrutinizing the goal and objectives of the cultural planning exercise. Such a goal setting process largely defines ways of resource management, both from a cultural and a financial point of view. Bringing on board the different views and perceptions of community groups at this stage provides guidance to planners as to the locally-adjusted and value-driven goal and objectives that need to be pursued and their prioritization. Process and outcomes of this stage strongly relate to (a) and (b) of the cultural heritage cycle (Figure 3).

- (c)

- ‘Plan and evaluate’: structuring and evaluating plans for featuring future developmental perspectives that are grounded, among others, on the sustainable and resilient exploitation of (U)CH is a quite decisive stage of the planning cycle. The same holds for community engagement and its empowerment in order to substantially participate at this stage. The value of participation lies in the fact that this stage addresses the structuring and evaluation of plans that embrace local values and inspirations; while serving at the best possible way local expectations [86]. Process and outcomes of this stage relate to (a), (b), and (d) of the cultural heritage cycle (Figure 3).

- (d)

- ‘Implement plans’: plans, as outcomes of previous stages of the planning cycle, are implemented on the basis of a range of policy packages. Towards this end, commitment of community stakeholders to policy decisions demarcates success of plans’ implementation. The more intense community engagement is at previous stages the more successful the implementation of plans and related policy actions will be. In this respect, it is quite important to feature a participatory process that engages community actors at all stages of the planning cycle. However, this is not always feasible, although desirable, due to time and budget limitations but also other constraints [31,87,88,89]. This stage relates to the heritage cycle as a whole (Figure 3).

- (e)

- ‘Monitoring results of plans’: an inseparable part of each planning process, targeting assessment of plans’ implementation in order for re-orienting or reinforcing policy endeavors. Community engagement can support this stage by providing information on the performance of the specific plan and related policy measures towards reaching the goals and objectives set. In case of low performance, they can also support identification of failures and possible proposals for remediation or reorientation of policy measures. This stage is closely related to all stages of the heritage cycle (Figure 3).

3.3. Conducting (U)CH Participatory Planning Processes

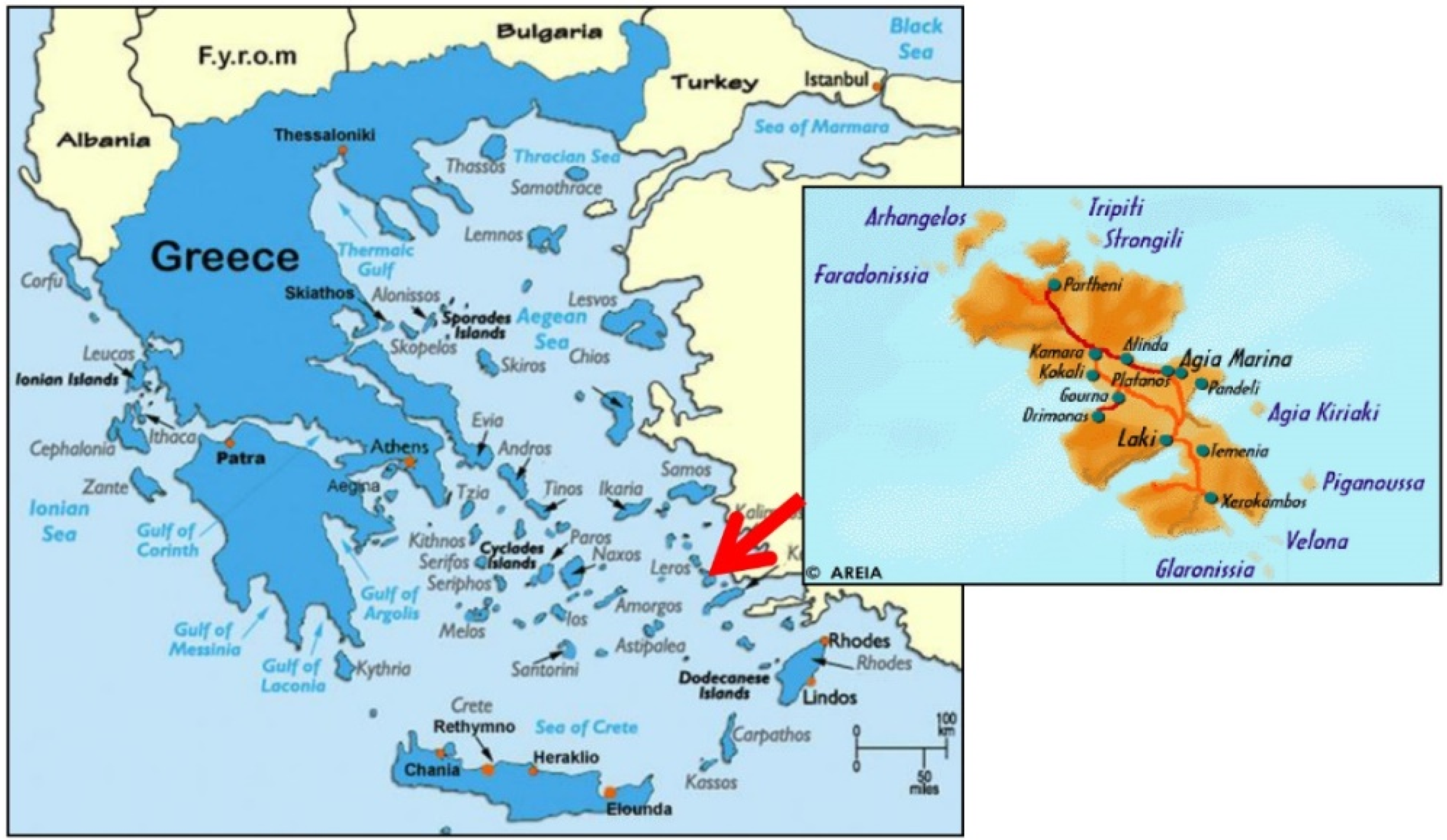

4. Lessons Learned from the Leros Island (U)CH Participatory Case Study

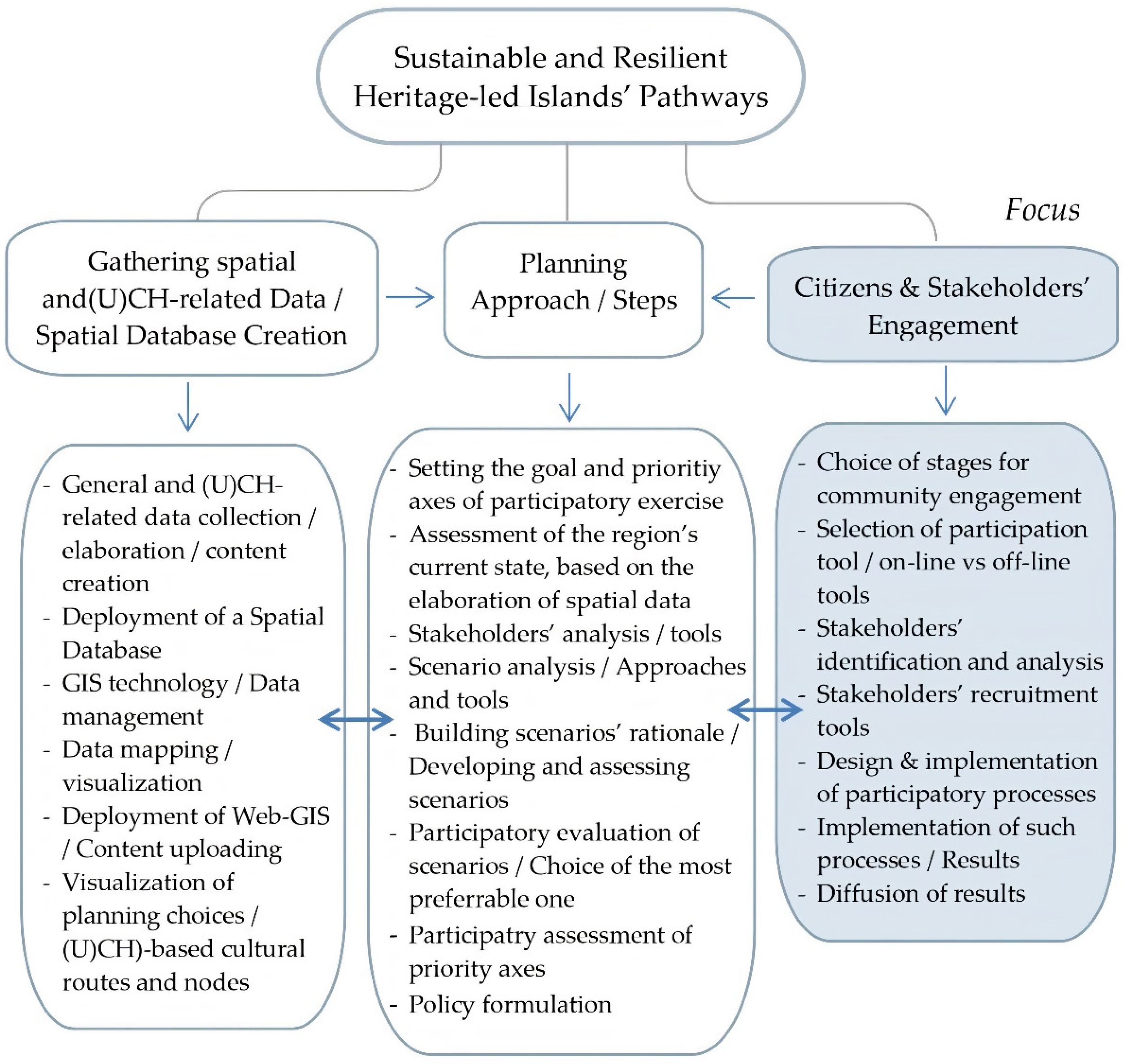

4.1. Sustainable Management of Leros (U)CH—Methodological Approach

- External decision environment stream, shedding light on developments that are framing planning outcomes and related policy choices in the specific case study; and

- Internal environment stream, providing a deep insight into the current state of Leros Island per se. This is of decisive importance, setting the ground upon which planning options for future heritage-led developmental trails of Leros are explored.

- Sectoral issues, e.g., culture, tourism;

- Spatial issues, e.g., land and marine character and uses;

- Historical issues, e.g., WWII (U)CH as part of the national but also European and global historical course;

- Societal issues, e.g., remembrance of historical events and human losses;

- Environmental issues, e.g., UCH as marine reef or a source of sea pollution;

- Governance issues, e.g., WWII (U)CH policy making at different spatial levels; and

- Developmental issues, perceiving (U)CH as a resource and a ‘production factor’.

- Spatial database deployed in this study; and

- Web-GIS application, developed for communicating planning choices to Leros community.

- Collection and elaboration of various types of spatial data in pillar 1 set the ground for a first assessment of the current state of this environment;

- Further elaboration of these data in pillar 2 allows for useful—quantitative and qualitative—inferences to be drawn;

- Finally, data gathered in previous steps is complemented in pillar 3 by means of community engagement processes, enriching the planning process with locally-driven data.

4.2. Engaging Leros Community in the Planning Endeavour—Empirical Results

4.2.1. The Participatory Process—Means, Context, and Stages of Community Engagement

- The stage of assessing current state of the island, aiming at gathering participants’ views as to the level of (U)CH sustainable exploitation for local development purposes;

- The stage of setting goal and priority axes for action, as an important starting point of the Leros planning exercise that needs to embed local community’s views, perspectives and priorities;

- The stage of assessing proposed scenarios, which demarcates distinct planning choices as to the potential future developmental perspectives of Leros Island. These need to be validated and eventually improved, but also secure consensus at the community level and better reflect laypeople values and future expectations.

- Assessment of the current state of exploitation of Leros’ cultural capital;

- Choice of three, out of the eight (Table 2), most preferable priority axes for building up a heritage-led strategic cultural development plan;

- Selection of the most preferable scenario narrative, out of (Table 2): (i) Scenario A’, entitled “Leros: From a ‘Soul-House’ to a Place of Multiple-Opportunities”, presenting a multi-thematic, spatially-concentrated—in the form of cultural nodes—model of cultural tourism development; and placing emphasis on balanced, heritage-led, local development concerns; (ii) Scenario B‘, entitled “Leros: An ’Open Museum‘ of European Cultural Heritage and Identity”, featuring a more decentralized spatial pattern, establishing island-wide cultural routes, connecting WW II heritage assets;

- Enrichment of the content of the proposed scenarios according to local experience, empirical knowledge, values and expectations.

4.2.2. Results and Discussion

- The potential of the valuable, and of global reach, (U)CH of Leros Island, according to respondents’ view, remains largely untapped, thus leaving, also, unexploited the quite promising developmental perspectives this can bring to the place;

- The value of WWII (U)CH in the eyes of local community is pretty high. They recognize the need to protect it and use it as a ‘production factor’ towards achieving a qualitative heritage-led cultural tourism destination profile. Scenario B’ in this respect, visioning Leros as “An ‘Open Museum’ of European Cultural Heritage and Identity” and having WWII (U)CH as the prevailing feature, rates first, at a distance from the second one proposed (Table 2);

- Participants realize the value of the local cultural identity PA1 as a main pillar for social and economic cohesion; and a means for coping with insularity drawbacks. Therefore, priority axis PA1 is rated first and at a distance from the rest ones;

- The priority axis PA4 that aspires to render Leros a peaceful, qualitative, authentic, and experience-based cultural destination rates second in community preferences. This reveals their desire towards developmental trails that keep close or do not disturb their legacy and identity. This issue, in turn, further reinforces the belief that they recognize and appreciate the value of their heritage and its distinct role in featuring local identity;

- Respondents also display a higher preference—third position in their rating—on PA8, that seeks to promote a fair and just development and remove inequalities inherent in the island. This is an important aspect, unveiling a strong solidarity culture and sense of community and belonging that seems to prevail among local population;

- Finally, priority axis PA7 is coming next to respondents’ choices, recognizing awareness raising as a means for (U)CH preservation and protection, as well as sustainable and resilient exploitation. Such a view reveals a mature community, realizing risks menacing integrity of their cultural heritage; and grasping knowledge and awareness as important assets in coping with these risks;

- Quite close to PA7 is PA2 that proposes an integrated management of land and underwater cultural heritage. This response was rather expected, taking into consideration the inseparable nature of the land and maritime CH as parts of the same narrative, i.e., remnants of the WWII.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- RanjbarI, M.; Shams Esfandabadi, Z.; Zanetti, M.-C.; Scagnelli, S.-D.; Siebers, P.-O.; Aghbashlo, M.; Peng, W.; Quatraro, F.; Tabatabaei, M. Three Pillars of Sustainability in the Wake of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kang, J.; Kim, K. Global Collaboration Research Strategies for Sustainability in the Post COVID-19 Era: Analyzing Virology-related National-funded Projects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Brandli, L.L.; Lange Salvia, A.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Platje, J. COVID-19 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Threat to Solidarity or an Opportunity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fuchs, M.; Baggio, R.; Hoepken, W.; Law, R.; Neidhardt, J.; Pesonen, J.; Zanker, M.; Xiang, Z. E-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A Call for Transformative Research. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mubeen, R.; Iorember, P.T.; Raza, S.; Mamirkulova, G. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism: Transformational Potential and Implications for a Sustainable Recovery of the Travel and Leisure Industry. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, H.G. Tourism Recovery and the Economic Impact: A Panel Assessment. Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.G.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving Tourism Industry Post-COVID-19: A Resilience-Based Framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Rebuilding Tourism for the Future: COVID-19 Policy Responses and Recovery, 2020. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137392-qsvjt75vnh&title=Rebuilding-tourism-for-the-future-COVID-19-policy-response-and-recovery (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Ocheni, S.I.; Ogaboh Agba, A.M.; Agba, M.S.; Eteng, F.O. Covid-19 and the Tourism Industry: Critical Overview, Lessons and Policy Options. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 9, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.; Sinclair, M.T. Tourism Crisis Management: US Response to September 11. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 813–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, J.; Cantavella-Jorda, M. Tourism as a Long-Run Economic Growth Factor: The Spanish Case. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benjamin, S.; Dillette, A.; Alderman, D.H. “We Can’t Return to Normal”: Committing to Tourism Equity in the Post-Pandemic Age. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauanai-Kay, T. Tourism and the Prostitution of Hawaiian Culture. Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. Available online: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/tourism-and-prostitution-hawaiian-culture (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Simmons, D.G. Community Participation in Tourism Planning. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castéran, H.; Roederer, C. Does Authenticity Really Affect Behavior? The Case of the Strasbourg Christmas Market. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Katsoni, V. A Strategic Policy Scenario Analysis Framework for the Sustainable Tourist Development of Peripheral Small Island Areas–the Case of Lefkada-Greece Island. Eur. J. Future Res. 2015, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Yu, L.; Jiang, L. Authenticity and Loyalty at Heritage Sites: The Moderation Effect of Postmodern Authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaden, P.; Harron, S. Alternative Tourism and Adaptive Change. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuculeski, N.; Petrovska, I.; Mircevska, T.P. Emerging Trends in Tourism: Need for Alternative Forms in Macedonian Tourism. Rev. Innov. Compet. 2015, 1, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.J. Trends and Patterns in Sustainable Tourism Research: A 25-Year Bibliometric Analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranck, S.R. An Attempt at Autonomous Development: The Case of the Tuti Guest Houses, Papua, New Guinea. In Ambiguous Alternative: Tourism in Small Developing Countries; Britton, S., Clarke, W.C., Eds.; University of the South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 1987; pp. 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Report on Investing in Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/events/culturaldiversityday/pdf/Investing_in_cultural_diversity.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Crossick, G.; Kaszynska, P. Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture-The AHRC Cultural Value Project; Arts and Humanities Research Council: Swindon, UK, 2016; Available online: https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/publications/cultural-value-project-final-report/ (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Russo, A.-P.; Richards, G. Reinventing the Local in Tourism-Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andriotis, K.; Agiomirgianakis, G. Market Escape through Exchange: Home Swap as a Form of Non-Commercial Hospitality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 17, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theodora, Y. Cultural Heritage as a Means for Local Development in Mediterranean Historic Cities—The Need for an Urban Policy. Heritage 2020, 3, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papazoglou, G. Society and Culture: Cultural Policies Driven by Local Authorities as A Factor in Local Development—The Example of the Municipality of Xanthi-Greece. Heritage 2019, 2, 2625–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. Adopted at the General Conference of UNESCO in Paris, France, 15 October–3 November 2001. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001429/142919e.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Argyropoulos, V.; Stratigea, A. Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean. Heritage 2019, 2, 1588–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Integrated Maritime Policy and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 3rd National Conference of Urban and Regional Planning and Regional Development, Volos, Greece, 24–27 September 2018. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage 2019, 2, 938–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manders, M.R. Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage; (UNIT 3); UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2012; Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/pdf/UNIT3.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Leveraging Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) Potential for Smart and Sustainable Development in Mediterranean Islands. In Proceedings of the 20th Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2020; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, O.B., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Eufemia, T., Torre, C.M., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (The Faro Convention). Signed by the Member States of the Council of Europe in Faro, Portugal, 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- COM(2018) 267 Final. A New European Agenda for Culture, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, European Commission in Brussels, Belgium, 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0267&from=EN (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- European Union. The New Cohesion Policy 2021–2027; Official Journal of the European Union: L 231/64, 30.06.2021; European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Leka, A.; Nicolaides, C. Small and Medium-Sized Cities and Island Communities in the Mediterranean: Coping with Sustainability Challenges in the Smart City Context. Ιn Smart Cities in the Mediterranean-Coping with Sustainability Objectives in Small and Medium-sized Cities and Island Communities; Stratigea, A., Kyriakides, E., Nicolaides, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Panagou, N.; Kokkali, A.; Stratigea, A. Towards an Integrated Participatory Marine and Land Spatial Planning Approach at the Local Level—Planning Tools and Barriers Involved. Reg. Sci. Inq. 2018, 10, 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarias, A.; Sayas, J. Urban Sprawl in the Mediterranean: Evidence from Coastal Medium-sized Cities. Reg. Sci. Inq. 2018, 10, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarias, A.; Stratigea, A. High-Resolution Spatial Data Analysis for Monitoring Urban Sprawl in Coastal Zones: A Case Study in Crete Island. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications-ICCSA 2021, LNCS 12958, 21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Part, X., Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Tarantino, E., et al., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 75–90, ISBN 978-3-030-87016-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervaki, A. Chapter 8 The Ecosystem Approach and Public Engagement in Ocean Governance: The Case of Maritime Spatial Planning. In The Ecosystem Approach in Ocean Planning and Governance; Brill|Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 223–255. ISBN 9789004389984. [Google Scholar]

- Langlet, D.; Westholm, A. Realizing the Social Dimension of EU Coastal Water Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COM(2007)575. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52007SC1279:EN:HTML (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Koivurova, T. A Note on the European Union’s Integrated Maritime Policy. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 2009, 40, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/56/EC. Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Marine Environmental Policy–Marine Strategy Framework Directive; Official Journal of the European Union: L 164/19, 25.6.2008; European Union: Luxembourg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam, P.C.; Uusitalo, L.; Patricio, J.; Piroddi, C.; Queiros, M.A.; Teixeira, H.; Rossberg, G.A.; Sagarminaga, Y.; Hyder, K.; Niquil, N.; et al. Uses of Innovative Modelling Tools within the Implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loizidou, X.I.; Loizides, M.I.; Orthodoxou, D.L. Marine Strategy Framework Directive: Innovative and Participatory Decision-Making Method for the Identification of Common Measures in the Mediterranean. Mar. Policy 2017, 84, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Petrić, L. Mediterranean Protected Areas in the Era of Overtourism—Challenges and Solutions; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-69193-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, K. The EU in the Eastern Mediterranean—A “Geopolitical” Actor? Orbis 2021, 65, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, A.; Puddu, M.; Venturini, S.; Giupponi, C. Assessment of Coastal Risks to Climate Change related Impacts at the Regional Scale: The Case of the Mediterranean Region. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallega, A. The Coastal Cultural Heritage Facing Coastal Management. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantasano, N.; Caloiero, T.; Pellicone, G.; Aristodemo, F.; De Marco, A.; Tagarelli, G. Can ICZM Contribute to the Mitigation of Erosion and of Human Activities Threatening the Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Coastal Landscape of Calabria? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanés Batista, C.; Planas, J.A.; Pelot, R.; Núñez, J.R. A New Methodology Incorporating Public Participation within Cuba’s ICZM Program. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 186, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean. Adopted by the Council of Europe, Madrid, Spain. 21 January 2008. Available online: https://www.pap-thecoastcentre.org/pdfs/Protocol_publikacija_May09.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Barale, V.; Özhan, E. Advances in Integrated Coastal Management for the Mediterranean & Black Sea. J. Coast. Conserv. 2010, 14, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Niavis, S.; Papatheochari, T.; Coccossis, H. Supporting Stakeholder Analysis Within ICZM Process in Small and Medium-Sized Mediterranean Coastal Cities with The Use Of Q-Method. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2019, 14, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kies, F.; Monge-Ganuzas, M.; De los Rios, P. Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Framework and Ecosystem Approach: Eutrophication Phenomenon at the Mediterranean Sea. Bull. Soc. R. Des Sci. Liège 2020, 89, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Douvere, F. The Importance of Marine Spatial Planning in Advancing Ecosystem-Based Sea Use Management. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, S.J.; Adamowicz, W.L.; Beck, W.M.; Craig, B.; Essington, E.T.; Fluharty, D.; Rice, J.; Sanchirico, N.J. Marine Spatial Planning in Practice. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 117, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Jones, J.S.P. The Emerging Policy Landscape for Marine Spatial Planning in Europe. Mar. Policy 2013, 39, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2014/89/EU. Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning; Official Journal of the European Union: L 257/135, 28.8.2014; European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP/MAP. Mediterranean Strategy for Sustainable Development 2016–2025 (MSSD). Valbonne. Plan Bleu, Regional Activity Centre, 2016. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/7097/mssd_2016_2025_eng.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Guiding Informed Choices on Participation Tools in Spatial Planning: An e-Decision Support System. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2019, 8, 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalal-Clayton, B.; Bass, S. Sustainable Development Strategies: A Resource Book. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 1-85383-946-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J. Methods for IA: The Challenges and Opportunities Ahead. Environ. Model. Assess. 1998, 3, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Wales, C. The Theory and Practice of Citizens’ Juries. Policy Politics 1999, 27, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt, M.; Rijkens-Klomp, N. Look in the Mirror: Reflection on Participation in Integrated Assessment from a Methodological Perspective. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2002, 12, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A.; Leka, A. Gathering Global Intelligence for Assessing Performance of Smart, Sustainable, Resilient, and Inclusive Cities (S2RIC): An Integrated Indicator Framework. In Citizen-Responsive Urban E-Planning: Recent Developments and Critical Perspectives; Silva, C.N., Ed.; IGI Global: International Academic Publisher: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 305–345. ISBN 9781799840183. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G. Our Common Future, The World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Agenda 21-Earth Summit-The United Nations Programme of Action from Rio; United Nations Department of Public Information: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Citizens, Experts, and the Environment-The Politics of Local Knowledge; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keiner, M. The Future of Sustainability; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A. Theory and Methods of Participatory Planning; Hellenic Academic Electronic Books, Kallipos: Athens, Greece, 2015; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11419/5428 (accessed on 14 July 2021). (In Greek)

- Nummi, P. Crowdsourcing Local Knowledge with PPGIS and Social Media for Urban Planning to Reveal Intangible Cultural Heritage Crowdsourcing Local Knowledge with PPGIS and Social Media for Urban. Urban Plan. 2018, 3, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nared, J.; Bole, D. Participatory Research on Heritage-and Culture-based Development: A Perspective from South-East Europe. In Participatory Research and Planning in Practice; Nared, J., Bole, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.N. The E-Planning Paradigm–Theory, Methods and Tools: An Overview. In Handbook of Research on E-Planning–ICTs for Urban Development and Monitoring; Silva, C.N., Ed.; Information Science Reference: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–14. ISBN 9781615209293. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y. On Life Cycle of Cultural Heritage Engineering Tourism: A Case Study of Macau. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2011, 1, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, M.; Clegg, S.; Sillince, J. The Importance of Learning to Differentiate between “Hard” and “Soft” Knowledge. Commun. IBIMA 2008, 6, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, Scientific and Technical Advisory Body, Report, Recommendations and Resolutions, 2012. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/underwater-cultural-heritage/meetings/meetings-of-advisory-body/third-meeting/ (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- Thurley, S. Into the Future-Our Strategy for 2005–2010. Conserv. Bull. 2005, 49, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie-Edwards, M. England’s Protected Wreck Diver Trails and the Economic Value 5th of a Protected Wreck. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Underwater Archaeology: A heritage for mankind, Cartagena, Colombia, 15–18 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spilanis, J. European Island and Political Cohesion; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 2012; ISBN 978-960-01-1544-4. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C.; Desogus, G.; Stratigea, A. Territorial Cohesion in Insular Contexts: Assessing External Attractiveness and Internal Strength of Major Mediterranean Islands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Releasing Cultural Tourism Potential of Less-privileged Island Communities in the Mediterranean: An ICT-enabled, Strategic, and Integrated Participatory Planning Approach. In The Impact of Tourist Activities on Low-Density Territories: Evaluation Frameworks, Lessons, and Policy Recommendations; Marques, R.P., Melo, A.I., Natário, M.M., Biscaia, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 63–93. ISBN 978-3-030-65524-2. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Indulging in the ‘Mediterranean Maritime World’: Diving Tourism in Insular Territories. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications-ICCSA 2021, LNCS 12958, 21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Part, X., Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Tarantino, E., et al., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 59–74, ISBN 978-3-030-87016-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Public Participation Methods: A Framework for Evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, N.H. Participatory Methods Toolkit–A Practitioner’s Manual; Belgian Advertising: Roeselare, Belgium, 2003; ISBN 90-5130-447-1. Available online: https://cris.unu.edu/sites/cris.unu.edu/files/Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Koutsi, D. Integrated Management of Land and Underwater Cultural Resources as a Pillar for the Development of Isolated Insular Islands. Master’s Thesis, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 20 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krommyda, V.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Integrating Offline and Online Participation Tools for Engaging Citizens in Public Space Management–Application in the Peripheral Town of Karditsa-Greece. Int. J. Electron. Gov. 2019, 11, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, S. International Public Participation Models 1969–2020. Available online: https://www.bangthetable.com/blog/international-public-participation-models/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Am. Inst. Plan. J. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roniotes, A.; Malotidi, V.; Virtanen, H.; Vlachogianni, T. A Handbook on the Public Participation Process in the Mediterranean. Text Version of the MedPartnership e-Learning Module, 2015. Available online: https://mio-ecsde.org/project/a-handbook-on-the-public-participation-process-in-the-mediterranean-mio-ecsde-2015/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- NOAA. Introduction to Stakeholder Participation. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/data/digitalcoast/pdf/stakeholder-participation.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.-A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for Planning the Development of Smart Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Spatial Data Management and Visualization Tools and Technologies for Enhancing Participatory e-Planning in Smart Cities. In Smart Cities in the Mediterranean-Coping with Sustainability Objectives in Small and Medium-Sized Cities and Island Communities; Stratigea, A., Kyriakides, E., Nicolaides, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 31–57. ISBN 987-3-319-54557-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Lin, Y.; Derudder, B. Demonstration of Public Participation and Communication through Social Media in the Network Society within Shanghai. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vogt, S.; Förster, B.; Kabst, R. Social Media and E-Participation: Challenges of Social Media For. Int. J. Public Adm. Digit. Age 2014, 1, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouzguenda, I.; Fava, N.; Alalouch, C. Would 3D Digital Participatory Planning Improve Social Sustainability in Smart Cities? An Empirical Evaluation Study in Less-Advantaged Areas. J. Urban Technol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BUND. Online Participation in Climate Policy-A Guide to Engaging Stakeholders Digitally, 2020. Available online: https://www.bund.net/fileadmin/user_upload_bund/publikationen/klimawandel/klimawandel_iki_participation_paper.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Leros. Available online: http://leros.homestead.com/geographyGR.html (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- Areianet. Available online: http://www.hri.org/infoxenios/english/dodecanese/leros/ler_map.html (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- Law 3983/2011. National Strategy for the Protection and Management of the Marine Environment-Harmonization with Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and Council of 17 June 2008 and Other Provisions. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-periballon/prostasia-thalassiou-periballontos/n-3983-2011.html (accessed on 4 October 2021). (In Greek).

- Law 4546/2018. Transposition into Greek Legislation of Directive 2014/89/EU “Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning” and Other Provisions. Available online: https://www.taxheaven.gr/law/4546/2018 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Law 3409/2005. Recreational Diving and Other Provisions. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-naytilia-nausiploia/kataduseis-anapsukhes/n-3409-2005.html (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Law 4688/2020. Special Forms of Tourism, Provisions for Tourism Development and Other Provisions. Available online: https://www.taxheaven.gr/law/4688/2020 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Burgers, G.-J. Tourism, Leisure and Cultural Heritage: The Challenge of Participatory Planning and Design. In Tourism and Regional Science. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives; Suzuki, S., Kourtit, K., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- COM(2014) 477. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe. Brussels, Belgium, 2014. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/culture/library/publications/2014-heritage-communication_en.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2021).

| Benefits for Planners/Decision Makers | Benefits for Citizens/Localities |

|---|---|

| Data collection, validation, and better understanding of the study context | Enriching local knowledge stock on aspects/challenges/constraints etc. of the external decision environment |

| Deployment of human-centric and place-specific UCH narratives/Positive impacts on implementation perspectives/Policy buy-in | Co-designing place- and human-centric UCH narratives |

| Conflicts’ management at early stages of the planning cycle—Consensus building | Maturing of participatory processes—Strengthening of local capacity for engagement and action |

| Communication and building of trust/Accountability and transparency | Raising awareness of local community as to the cultural/social/economic value of UCH |

| Legitimization of planning procedures and outcomes | Raising awareness of UCH protection/preservation and sustainable exploitation at the community level |

| Widely acceptable policy interventions targeting the sustainable and resilient exploitation of (U)CH | Locally-adjusted cultural management plans aligned with local visions and expectations |

| Networking among stakeholders |

| Rating of Scenarios | Rating of Priority Axes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Scenarios | Community Rating of Scenarios % | Proposed Priority Axes | Community Rating of Priority Axes % |

Vision of Leros Island in Scenario A’ “From a ‘Soul -House’ to a place of Multiple Opportunities” | 36 | PA1—Designation of local cultural identity as a pillar for economic development and social cohesion | 45 |

| PA2—Treatment of land and underwater cultural heritage in an integrated way | 27 | ||

| PA3—Integrated approach of natural and cultural resources | 21 | ||

| PA4—Development of alternative, experience-based, cultural tourism products | 35 | ||

Vision of Leros Island in Scenario B’ “An ‘Open Museum’ of European Cultural Heritage and Identity” | 64 | PA5—ICT-enabled promotion of land and underwater cultural heritage | 16 |

| PA6—Enhancement of local entrepreneurship and creation of value chains | 19 | ||

| PA7—Raising awareness of local community on the value of natural and cultural resources | 28 | ||

| PA8—Balanced cultural tourism development—removal of inequalities | 30 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework. Heritage 2021, 4, 3469-3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040192

Koutsi D, Stratigea A. Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):3469-3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040192

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoutsi, Dionisia, and Anastasia Stratigea. 2021. "Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework" Heritage 4, no. 4: 3469-3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040192

APA StyleKoutsi, D., & Stratigea, A. (2021). Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework. Heritage, 4(4), 3469-3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040192