Assessing the Performance of Current Strategic Policy Directions towards Unfolding the Potential of the Culture–Tourism Nexus in the Greek Territory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How effective have the current strategic policy directions been so far in promoting the culture–tourism complex, i.e., sustainable and resilient, authentic, experience-based and culture-related alternative tourism forms in Greece? Or, stated differently, have these directions succeeded in confining the traditional spatially concentrated, mainly in coastal and insular regions, and mass-related ‘3S’ (Sun–Sea–Sand) model, i.e., a resource-intensive and unsustainable one? Or has Greece taken steps towards altering the currently old-fashioned ‘summer myth’ narrative of the Greek tourism sector and motivating tourism entrepreneurship to invest in more sustainable and resilient projects that embrace the natural–cultural nexus?

- Do entrepreneurial decisions fit with the distribution of the abundant natural and cultural heritage of the Greek territory?

- How can technology-enabled spatial data management be used as a supportive policy tool for sustaining policy assessment and unveiling specific deficits in policy outcomes so that more informed or dedicated policy actions can be grasped?

2. Methodological Approach

- Evidence-based policy making, implying a sound and robust set of data, necessary for illuminating policy inefficiencies and orienting policy directions; and

- Integrated approach, which entails following the distinct steps of the policy cycle, each of which serves particular purposes and can draw upon knowledge, tools and approaches that emanate from a range of disciplines.

- Step 1: ‘Setting the Scene’. In this step, the key drivers of the external environment that can frame policy decisions regarding a problem at hand are identified. Concurrently, global key goals, such as sustainability and resilience, which are deemed to be overarching or ‘umbrella’ goals in each planning and policy exercise, affecting policy formulation with regard to each individual field, are considered. Based on the scope of this work, climate change as well as tourism demand trends are also perceived as important key drivers framing the decision environment. The aforementioned key drivers are already identified and briefly discussed in the introductory section of this work.

- Step 2: ‘Delving into the Policy Problem/Context’. This step elaborates on the problem addressed by a policy exercise and the relevant spatial context (e.g., local, regional, national or supranational). It implies a deep understanding of the specific attributes of both the problem at hand and its spatial context so as to ground the policy exercise in field-related evidence [49]. In the particular policy exercise of the present research, the type and spatial distribution of cultural and natural resources as well as entrepreneurship developed on the basis of these resources are perceived as the key elements of this step. Thus, using a national spatial reference, a data-driven thorough insight into the type and spatial distribution of both cultural and natural resources as well as tourism entrepreneurship is carried out, framing the processes/work of the subsequent steps.

- Step 3: ‘Defining Policy—Goals, Objectives and Targets’. Based on the previous steps, this step is associated with the articulation of a relevant policy for problem solving as well as the goals, objectives and targets to be reached by its implementation. Work undertaken in this step is characterized by the problem at hand and the specific spatial context (output of Step 2), while it also takes into consideration the key drivers and overarching policy goals of the external environment (output of Step 1). In the context of this step, alternative policy options are structured and evaluated (e.g., alternative scenarios and policy paths for their implementation) so as to end up with the most effective one, precisely formulate it and implement it. For the purpose of this work, however, it should be noted that the current policy framework and its goals, objectives and targets, mainly characterized by its financial (provision of incentives in support of tourism entrepreneurship) and spatial dimension (Special Framework for Spatial Planning for Tourism), are taken for granted; while it is precisely its effectiveness that is subjected to investigation and analysis in the subsequent steps. Therefore, the paper attempts to clarify the current policy directions and their specific goals, objectives and targets as these unfold in relative policy framework at this stage.

- Step 4: ‘Assessing Policy Outcomes and Targets’ Achievement’. This refers to a critical step of the policy cycle, which aims at assessing a certain policy’s performance regarding predefined end states. Identification of divergences or gaps between predefined policy goals, objectives and targets on the one hand and those actually achieved by policy implementation on the other, coupled with interpretation of these gaps, can provide the necessary input for Step 5 for the management of policy failures by a properly informed adjustment or reorientation of the policy decisions. This stage forms the core of this work as a means to identify gaps and thus steer more knowledgeable policy remediation towards desired outcomes. The key question is whether and to what extent tourism entrepreneurship goes hand in hand with natural and cultural assets, or, stated differently, how effective the Greek developmental and spatial policies are for promoting a successful ‘marriage’ of culture–tourism. The response to this question displays the capabilities of technological tools for managing the sizeable data sets produced in Step 2 of the present study. The vital role of such tools is highlighted as highly supportive data management and analysis frameworks in the policy cycle context for policy formulation, evaluation, assessment and monitoring. In the present work, these tools possess a decisive role in the work carried out in Steps 2 and 4 (see Figure 2).

- Step 5: ‘Monitoring/Adjusting/Reorienting Policy’. This step rests upon the continuous monitoring of the outcomes produced by a certain policy and the remediation of the previously identified gaps (Step 4) or gaps emerging from potential developments in the external environment that may have adverse effects on the policy issue at hand. When such outcomes are observed, the final process pertaining to this step is to raise a call to action (e.g., the pandemic crisis’ impact on policy and the need for readjustment of previous goals). Tracking such irregularities can trigger and inform remediation action by means of adjusting, reorienting or calibrating policy decisions.

3. Delineating the Spatial Context: Mapping the Distribution of Natural and Cultural Resources and Related Tourism Entrepreneurship in Greece

3.1. Data Sources and Limitations

3.2. Mapping Natural and Cultural Resources at the Regional (NUTS 2) Level

- A large portion of the Region of the North Aegean, an insular region that comprises the islands of the northeastern Aegean Sea, is occupied by evenly distributed protected areas of great ecological importance, while numerous wildlife refuges, NATURA 2000 areas and thermal resources are detected. These natural resources can become the ‘vehicle’ for the development of nature-based and spa tourism, as well as health and wellness tourism. The Region of the North Aegean is also characterized by a complex mosaic of culture and civilization, composed of UNESCO World Heritage sites, traditional settlements, industrial heritage sites, archaeological sites and medieval and ancient castles.

- A great part of the Region of the South Aegean, an insular region that consists of the Cyclades and Dodecanese Island complexes located in the central and southeastern Aegean Sea, is covered with protected areas of major environmental significance and exhibits a relatively uniform distribution pattern. Moreover, plenty of wildlife refuges, as well as thermal resources, can be found here. As in the case of the North Aegean, the Region of the South Aegean has the potential to develop alternative experience-based tourism forms, founded on the promotion of nature, health and wellness. As far as cultural capital is concerned, this region possesses traditional settlements, industrial heritage and archeological sites, catholic cathedrals and fully preserved medieval castles.

- The Region of Crete, an insular region that includes the island of Crete and numerous neighboring islands and islets, has a significant stock of natural and cultural resources composed of protected areas, evenly distributed wildlife refuges, rivers suitable for sports and physical activities, traditional settlements, archeological sites, UNESCO World Heritage sites and museums of various types.

- A considerable part of the Region of Peloponnese, a mainland region located in southern Greece, and the Region of Central Greece, a mainland region that covers the eastern half of Central Greece, including the island of Euboea, are occupied by protected areas and wildlife refuges, with both being evenly dispersed, while thermal resources and several rivers suitable for sports and physical activities are also found here. These resources can contribute to the development of nature-based tourism. Furthermore, this region has a great variety of archaeological sites, museums of various types and a significant network of scattered traditional settlements.

- The Regions of Western Greece, located in the western part of mainland Greece; Thessaly, a mainland region in Central Greece; Western Macedonia, situated in northwestern Greece; Central Macedonia, covering the central part of northern Greece; and Epirus, located in the northwest part of mainland Greece, have the opportunity to develop nature-based health, wellness and sports tourism since a significant part of them is covered with protected areas of particular ecological importance, evenly distributed wildlife refuges and national parks, while thermal resources, rivers and lakes are also detected. These regions also possess archaeological sites, UNESCO World Heritage sites (in the Region of Western Greece), museums of various types, religious monuments, ancient and medieval castles and several traditional settlements.

- The Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, situated in the northeastern part of the country, has opportunity to develop nature-based health and wellness as well as sports tourism activities since it is characterized by an extremely wealthy natural environment, composed of evenly distributed protected areas, wildlife refuges, thermal resources and several rivers. Furthermore, it possesses numerous traditional settlements, archaeological and historical sites, castles, museums and religious monuments. Owing to the location and the historical evolution of this region, special temples and places of worship, such as mosques and other various types of Islamic monuments, can be found.

- The Region of the Ionian Islands includes all the Ionian Islands, apart from the island of Kythera, and has extended protected areas of great ecological importance as well as several wildlife refuges evenly distributed across the regional units. These resources can decisively contribute to the development of nature-based tourism. Regarding its cultural profile, this region has several traditional settlements, religious monuments, archaeological sites and museums of various types.

3.3. Mapping Tourism Entrepreneurship at the Regional (NUTS 2) Level

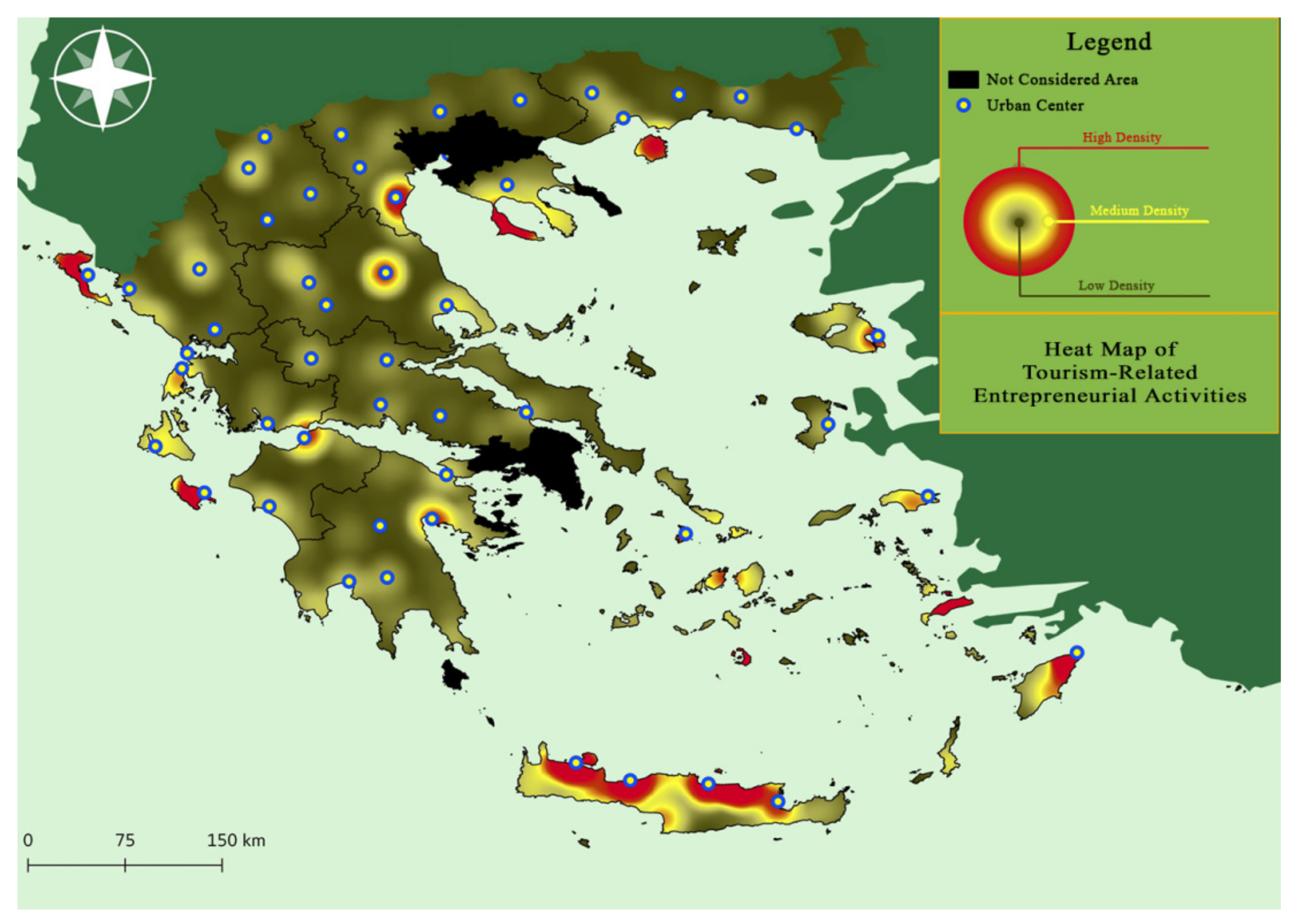

- Tourism-based entrepreneurial activities are mainly concentrated in the coastal (Nafplio, Patras, Volos, Chalkidiki, etc.) and insular parts of the country (Crete, Ionian Islands, Rhodes, Cyclades, etc.). This is due to the long-lasting national developmental and tourism policy, which has been promoting, almost exclusively, the ‘Sun–Sea–Sand’ model, thus favoring the explosive blossoming of mass tourism in the coastal and insular areas. As a result, such places have been drastically boosted for decades, a fact that has unavoidably led to severe regional disparities between the coastal/insular areas and the hinterland, with the latter remaining in the shadows, since its natural and cultural potential has been totally marginalized by the dominant tourism trends.

- Figure 5 makes apparent the fact that the coastal parts of both the insular areas and the mainland form a continuous tourism-oriented entrepreneurial front, a U-shaped form that extends from the northern borders of the Ionian Islands Region to the coastal areas of the Region of Western Greece and the Peloponnese (to the south), while it proceeds to the Region of Crete and then moves again up to the north, towards the Regions of the South and North Aegean.

- The spatial structure of tourism-related businesses, located in the hinterland, reveals a twofold inequality. On the one hand, tourism entrepreneurship appears to significantly lag behind, contrary to the coastal and insular areas, as they exhibit substantially lower density. On the other hand, imbalances emerge within these mainland regions, since tourism business activity exhibits higher density around urban centers and a low or medium degree of diffusion as the distance from the urban fabric starts to increase. In addition, there are many Greek locales in which tourism-based businesses are literally non-existent.

4. Current Policy Frameworks for Tourism Development in Greece: A Succinct Review

4.1. General Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development

4.2. Special Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development for Tourism

4.3. New Development Law for Investment Incentives (L. 4399/2016)

- Establishment or expansion of three-star (or higher) hotels.

- Modernization of integrated hotels that are classified as at least three-star hotels or are upgraded to that category (or higher).

- Expansion and modernization of integrated hotels that have ceased their operation.

- Establishment, expansion and modernization of three-star (or higher) integrated organized tourist campsites.

- Establishment and modernization of integrated hotels that occupy traditional or preservable buildings and belong or are upgraded to the two-star category at least.

- Founding of complex tourist accommodation facilities.

- Establishment of special interest tourism infrastructures (conference centers, golf courses, tourist ports, ski resorts, theme parks, thermal tourism facilities, etc.).

- Submission of investment plans for the creation of agro-tourism and wine tourism facilities by organized business clusters.

- Establishment of youth hostels.

4.4. Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialization (RIS3)

5. Assessing Entrepreneurial Exploitation of Natural and Cultural Capital: Critical Remarks

- The first step, which aims at exploring disharmonies among the distinct constituents of the national policy framework (Section 4) that restrain the consolidation of the culture–tourism complex, i.e., the intertwining of cultural assets with tourism; and

- The second step , which addresses the spatial counterpart of these disharmonies, i.e., the gap between the spatial pattern of natural/cultural capital and that of tourism entrepreneurship, as discussed in Section 3.

5.1. Assessing Coherence of Strategic Policy Frameworks: Key Findings and Critical Remarks

5.2. Assessing Spatial Repercussions of the Strategic Policy Frameworks in Enacting the Culture–Tourism Nexus

- Cultural resources are almost evenly scattered throughout the country, with most areas possessing, to one degree or another, cultural wealth. In some cases, places that do not rely on tourism for their local prosperity, e.g., Larissa or Serres (mainland cities), exhibit, in terms of spatial density analysis of cultural data (but ignoring the magnitude of the resources), a dispersion akin to that of areas characterized by heavy tourism (e.g., Crete and the South Aegean).

- At the same time, although these places are considered ‘culturally equivalent’, the spatial organization of tourism entrepreneurship, which expresses the degree of exploitation of cultural resources, follows a substantially different distribution. The prevalent spatial pattern is highly marked by a significant concentration of entrepreneurial activities in coastal and insular regions. It should also be noted that insular areas exhibit more intense spatial patterns compared to the coastal parts of the mainland.

- The lack and, in many cases, absence of cultural tourism entrepreneurship observed in the Greek mainland suggests that the respective cultural resources have not managed to attract business interests thus far due to the low investment returns these are expected to deliver to the entrepreneurial community. This deficit is justified either by stringent terms and restrictions imposed on the exploitation of these resources (e.g., strict legislative frameworks) or by the nature of the promoted tourism development scheme per se, which may completely marginalize cultural heritage (e.g., the Sun–Sea–Sand model), since the latter is perceived as meaningless in relation to the blossoming of the former.

5.3. Assessing Spatial Repercussions of the Strategic Policy Frameworks in Enacting the Nature–Tourism Nexus

- All Greek territories are endowed with exceptional natural reserves, with the western and the southern part of the mainland displaying denser spatial concentrations. Moreover, mature and popular tourist destinations (mostly coastal and insular places) appear to possess poorer natural capital in comparison to those located in the Pindos–Peloponnese axis (mainland) and barely depend (or do not depend at all) on tourism.

- National natural capital has made a subtle contribution to the development of respective tourism-based entrepreneurial activities. Empirical data on the Greek tourism sector, however, reveal that the natural beauty of landscapes acts as a complement to the enrichment and differentiation of the tourist product/experience.

5.4. Spatial Interelationship between the Nature–Culture Ensemble and Related Tourism Entrepreneurship

- The whole of Greece is gifted with extraordinary natural and cultural resources that render the country an extremely significant environmental and cultural hub on a global scale. These resources are found, to one degree or another, in all Greek regions and constitute a remarkable reserve, which, when sustainably utilized and promoted, may be immensely conducive to regional development and substantially boost the national economy. Even areas with limited relevant resources but with long traditions and specialization in a particular field can take advantage of such opportunities, e.g., the Thessalian plain with agro-tourism or the city of Ptolemaida with educational and conference tourism for energy issues.

- The spatial interrelationship between natural and cultural resources on the one hand and tourism entrepreneurship on the other, as is illustrated in Figure 9b, reveals the domination of intensified spatial concentrations of entrepreneurial activities in already established tourist destinations as well as the strong commitment to a traditional pattern of mass tourism development, the ‘Sun–Sea–Sand’ model.

- Most of the regions in the hinterland, although possessing considerable natural and cultural capital, perform poorly in terms of forming a solid tourism-oriented entrepreneurial base. This is utterly paradoxical since mainland areas are, usually, equipped with more and better infrastructures and they are not confronted with the difficulties of coastal shipping, which adds an extra obstacle to physical transportation and diffusion of tourist flows. Furthermore, these regions are in closer proximity to the central European tourism markets (e.g., Germany and the United Kingdom) and are accessible by a greater variety of transport means (transnational highways, railways, etc.). In addition, mainland Greece offers a great wealth of resources of all kinds; it has a significantly larger population and access to a much more extended scientific base.

- As regards the tourism-oriented entrepreneurial activities in the coastal and insular areas, these exhibit a great degree of diffusion and dense spatial distribution, regardless of their proximity to urban centers. They follow either a linear pattern, parallel to the coast, or cover whole islands. Conversely, in mainland Greece, tourism-based entrepreneurship is distributed around urban centers, thus creating a narrow buffer zone (a donut-like structure) or a small islet of tourism development that surrounds the urban fabric.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- The national strategic frameworks for tourism conform in one way or another to challenges of the external environment. However, they seem to fall short at the stage of implementation, thus hardly laying the ground for sustainable and resilient future development of this sector and its close intertwining with the remarkable natural–cultural nexus of Greece. Additionally, these frameworks do not seem to have given significant impetus to the respective entrepreneurial community to mobilize towards such a direction.

- Very few areas, especially in mainland Greece, that are recognized by the strategic policy framework as appropriate for accommodating alternative in general and cultural tourism activities in particular have actually moved in this direction, i.e., attracting entrepreneurial interest and related nature- and culture-based tourism activities.

- Coastal zones and insular regions still remain the main recipients of tourists who are eager to enjoy the ‘summer myth’ narrative of Greece. This, in turn, has already displayed the repercussions of the capacity limits being severely exceeded and overtourism patterns, thereby endangering the sustainable and resilient future of these places. These repercussions seem to be exerting increasing pressures in these regions due to the high seasonality that is a core attribute of the national tourist product. The Greek ‘myth’, built mainly upon the ‘Sun–Sea–Sand’ model, seems in fact to be critical in terms of the seasonality concerns of the tourism sector, but also a main decision factor for motivating tourism entrepreneurship towards taking action at specific, established tourist destinations.

- The current strategic policy framework seems to fail in providing a positive outlook regarding a shift away from the ‘summer myth’ tourism developmental paradigm and the ongoing degradation of the natural–cultural nexus as well as the pressures exerted on local communities, an alarming phenomenon noticed especially in areas marked by overtourism trends.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chon, K.-S.; Olsen, M.D. Applying the strategic management process in the management of tourism organizations. Tour. Manag. 1990, 11, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoni, V. Tourism and Culture in the Age of Innovation; Stratigea, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISSN 2198-7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Leveraging Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) Potential for Smart and Sustainable Development in Mediterranean Islands. In Computational Science and its Applications—ICCSA 2020, Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Computational Science and its Applications (ICCSA 2020) Part VI, Cagliari, Italy, 1–4 July 2020; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Releasing Cultural Tourism Potential of Less-privileged Island Communities in the Mediterranean: An ICT-enabled, Strategic and Integrated Participatory Planning Approach. In The Impact of Tourist Activities on Low-Density Territories: Evaluation Frameworks, Lessons, and Policy Recommendations; Marques, R.P.F., Melo, A.I., Natário, M.M., Biscaia, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 63–93. ISBN 978-3-030-65524-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainability Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Katsoni, V.A. Strategic Policy Scenario Analysis Framework for the Sustainable Tourist Development of Peripheral Small Island Areas: The Case of Lefkada-Greece Island. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2015, 3, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stratigea, A.; Kavroudakis, D. (Eds.) Mediterranean Cities and Island Communities: Smart, Sustainable, Inclusive and Resilient; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-99443-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Pigram, J.J. (Eds.) Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability; Routledge: New York City, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 0-415-16001-4. (hbk). [Google Scholar]

- Angelevska-Najdeskaa, K.; Rakicevikb, G. Planning of Sustainable Tourism Development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism Development and the Environment: Beyond Sustainability? Earthscan: New York City, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. In Agenda 21; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, J.C.; Humphreys, C. The Business of Tourism, 11th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 10-1526459450. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, F. A New Approach to Sustainable Tourism Development: Moving beyond Environmental Protection, ST/ESA/2003/DP/29 DESA Discussion Paper No. 29. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. 2003. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/esa03dp29.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Movono, A.; Hughes, E. Tourism partnerships: Localizing the SDG agenda in Fiji. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Sánchez, A.R.; Ruiz-Chico, J.; Jiménez-García, M.; López-Sánchez, J.A. Tourism and the SDGs: An Analysis of Economic Growth, Decent Employment, and Gender Equality in the European Union (2009–2018). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, U.; Buffa, F. Marketing for Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dwyer, L.; Edwards, D.C.; Mistilis, N.; Roman, C.; Scott, N.; Cooper, C. Megatrends Underpinning Tourism to 2020: Analysis of Key Drivers for Change; CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd.: Brooke Pickering, Australia, 2008; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos, C.; Le Sager, P.; Bindi, M.; Moriondo, M.; Kostopoulou, E.; Goodess, C.M. Climatic changes and associated impacts in the Mediterranean resulting from a 2 °C global warming. Glob. Planet. Change 2009, 68, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedECC Network. Mediterranean Experts on Climate and Environmental Change, Risks Associated to Climate and Environmental Changes in The Mediterranean Region, Report. 2019. Available online: https://ufmsecretariat.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/MedECC-Booklet_EN_WEB.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- UNEP-WTO. Climate Change and Tourism—Responding to Global Challenges; World Tourism Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Kyriakides, E.; Nicolaides, C. (Eds.) Smart Cities in the Mediterranean: Coping with Sustainability Objectives in Small and Medium-sized Cities and Island Communities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 987-3-319-54557-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Rebuilding Tourism for the Future: COVID-19 Policy Responses and Recovery. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/rebuilding-tourism-for-the-future-covid-19-policy-responses-and-recovery-bced9859/ (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Benjamin, S.; Dillette, A.; Alderman, D.H. “We can’t return to normal”: Committing to tourism equity in the post-pandemic age. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.G.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving Tourism Industry Post-COVID-19: A Resilience-Based Framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridderstaat, J.; Croes, R.; Nijkamp, P. The Tourism Development–Quality of Life Nexus in a Small Island Destination. J. Travel Res. 2014, 55, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Semrad, K.J. The Relevance of Cultural Tourism as the Next Frontier for Small Island Destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 39, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, A. Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Tool for Sustainable Development. Glob. J. Commer. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 6, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Go, F.M. Heritage Tourism Destinations: Preservation, Communication and Development; Yüksel, A., Ed.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. A participatory methodological framework for paving alternative local tourist development paths—The case of Sterea Ellada Region. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2014, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A.; Katsoni, V. In Search of Participatory Sustainable Cultural Paths at the Local Level—The Case of Kissamos Province-Crete. In Tourism, Culture and Heritage in a Smart Economy—Proceedings of the Third International Conference IACuDIT, Athens, Greece, 19–21 May 2016; Katsoni, V., Upadhya, A., Stratigea, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Smartening up Participatory Cultural Tourism Planning in Historical City Centers. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 27, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Participatory Spatial Planning in Support of Cultural-Resilient Resource Management: The Case of Kissamos-Crete. In Mediterranean Cities and Island Communities: Smart, Sustainable, Inclusive and Resilient; Stratigea, A., Kavroudakis, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Makens, J.C.; Baloglu, S. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 7th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R. Virtual Tourism Destination Image: Glocal Identities Constructed, Perceived and Experienced. Ph.D. Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, R. Motivations of the heritage consumer in the leisure market: An application of the Manning-Haas demand hierarchy. Leis. Sci. 1993, 15, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.; Pritchard, M.P.; Smith, B. The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C. Towards an Architecture of Governance for Participatory Cultural Policy Making. In Proceedings of the Working Meeting on Active Citizens—Local Cultures—European Politics, Barcelona, Spain, 22 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- INHERIT Project. Investing in Heritage: A Guide to Successful Urban Regeneration; European Association of Historic Towns and Regions: Norwich, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Hatzichristos, T. Experiential marketing and local tourist development: A policy perspective. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2011, 2, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantino, V.; Culasso, F.; Racca, G. (Eds.) Smart Tourism; McGraw-Hill Education: Milan, Italy, 2018; ISBN 10-8838695024. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P.; Lane, B. Rural Tourism Development. In Trends in Outdoor Recreation, Leisure and Tourism, 1st ed.; Gartner, W.C., Lime, D.W., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- UNTWO. Tourism Market Trends 2002: World Overview and Tourism Topics; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2003; ISBN 978-92-844-0438-4. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Garrett-Petts, W.F.; MacLennan, D. Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry: Introduction to an Emerging Field of Practice. In Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry; Duxbury, N., Garrett-Petts, W.F., MacLennan, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Crawhall, N. The Role of Participatory Cultural Mapping in Promoting Intercultural Dialogue ‘We Are Not Hyenas’—A Reflection Paper; United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2007; Available online: http://www.iapad.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/nigel.crawhall.190753e.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- Weible, C.M.; Nohrstedt, D.; Cairney, P.; Carter, D.; Crow, D.A.; Durnová, A.P.; Heikkila, T.; Ingold, K.; McConnell, A.; Stone, D. COVID-19 and the policy sciences: Initial reactions and perspectives. Policy Sci. 2020, 53, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Listorti, G.; Basyte-Ferrari, E.; Acs, S.; Smits, P. Towards an Evidence-Based and Integrated Policy Cycle in the EU: A Review of the Debate on the Better Regulation Agenda. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2020, 58, 1558–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skok, J.E. Policy Issue Networks and the Public Policy Cycle: A Structural-Functional Framework for Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 1995, 55, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Spatial Data Management and Visualization Tools and Technologies for Enhancing Participatory e-Planning in Smart Cities. In Smart Cities in the Mediterranean; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, V. Cultural Resources and Tourism Entrepreneurship—Spatial Data Analysis for the Specialization of developmental Policies of the Tourist Sector for Every Greek Region. Master’s Thesis, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece, July 2018. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, J.; Martin, E. Spatial proximity is more than just a distance measure. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2012, 70, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Wallet, F. The role of proximity relations in regional and territorial development processes. In Regional Development and Proximity Relations—New Horizons in Regional Science; Torre, A., Wallet, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Pub: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 13-978-1781002889. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, C. Heat Maps in GIS. GIS Lounge. 20 May 2012. Available online: https://www.gislounge.com/heat-maps-in-gis/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Serraos, K.; Gianniris, E.; Zifou, M. The Greek spatial and urban planning system in the European context. In Complessitá e Sostenibilitá, Prospettive per i Territori Europei: Strategie di Pianificazione in Dieci Paesi, Rivista Bimestrale di Pianificazione e Progrettazione; Padovano, G., Blasi, C., Eds.; POLI.design: Milan, Italy, 2005; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for the Environment, Physical Planning and Public Works. General Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development; Official Government Gazette: Athens, Greece, 2008; Volume 128, pp. 2253–2300. Available online: http://gnto.gov.gr/sites/default/files/fek_1138_2009.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021). (In Greek)

- Cornelisse, M. Understanding memorable tourism experiences: A case study. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 8, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jamal, T. Touristic quest for existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry for the Environment, Physical Planning and Public Works. Special Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development for Tourism. 2009. Available online: https://www.msp-platform.eu/practices/special-framework-spatial-planning-and-sustainable-development-aquaculture (accessed on 18 May 2021). (In Greek).

- Greece. Statutory Framework for the Establishment of Private Investments Aid Schemes for the Regional and Economic Development of the Country; 2016 (Act No. 4399 of 2016), Official Government Gazette 117/A/22-06-2016; Official Government Gazette: Athens, Greece, 2016; Available online: https://ilfconsult.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/%CE%BD%CF%8C%CE%BC%CE%BF%CF%82-%CE%A6%CE%95%CE%9A-%CE%91-117-%E2%80%93-22.06.2016-%CE%95%CF%86%CE%B7%CE%BC%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%AF%CE%B4%CE%B1-%CF%84%CE%B7%CF%82-%CE%9A%CF%85%CE%B2%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%BD%CE%AE%CF%83%CE%B5%CF%89%CF%82..pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021). (In Greek)

- General Secretariat for Research and Innovation. Available online: http://www.gsrt.gr/ (accessed on 11 February 2017).

- General Secretariat for Research and Technology. National Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialization 2014–2020; General Secretariat for Research and Technology: Athens, Greece, 2015; Available online: http://www.gsrt.gr//Financing/Files/ProPeFiles19/RIS3V.5_21.7.2015.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2017). (In Greek)

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. 1998. Available online: https://hbr.org/1998/11/clusters-and-the-new-economics-of-competition (accessed on 14 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lampropoulos, V.; Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Assessing the Performance of Current Strategic Policy Directions towards Unfolding the Potential of the Culture–Tourism Nexus in the Greek Territory. Heritage 2021, 4, 3157-3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040177

Lampropoulos V, Panagiotopoulou M, Stratigea A. Assessing the Performance of Current Strategic Policy Directions towards Unfolding the Potential of the Culture–Tourism Nexus in the Greek Territory. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):3157-3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040177

Chicago/Turabian StyleLampropoulos, Vasileios, Maria Panagiotopoulou, and Anastasia Stratigea. 2021. "Assessing the Performance of Current Strategic Policy Directions towards Unfolding the Potential of the Culture–Tourism Nexus in the Greek Territory" Heritage 4, no. 4: 3157-3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040177

APA StyleLampropoulos, V., Panagiotopoulou, M., & Stratigea, A. (2021). Assessing the Performance of Current Strategic Policy Directions towards Unfolding the Potential of the Culture–Tourism Nexus in the Greek Territory. Heritage, 4(4), 3157-3185. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040177