By the Hand of Angelos? Analytical Investigation of a Remarkable 15th Century Cretan Icon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Multispectral Imaging

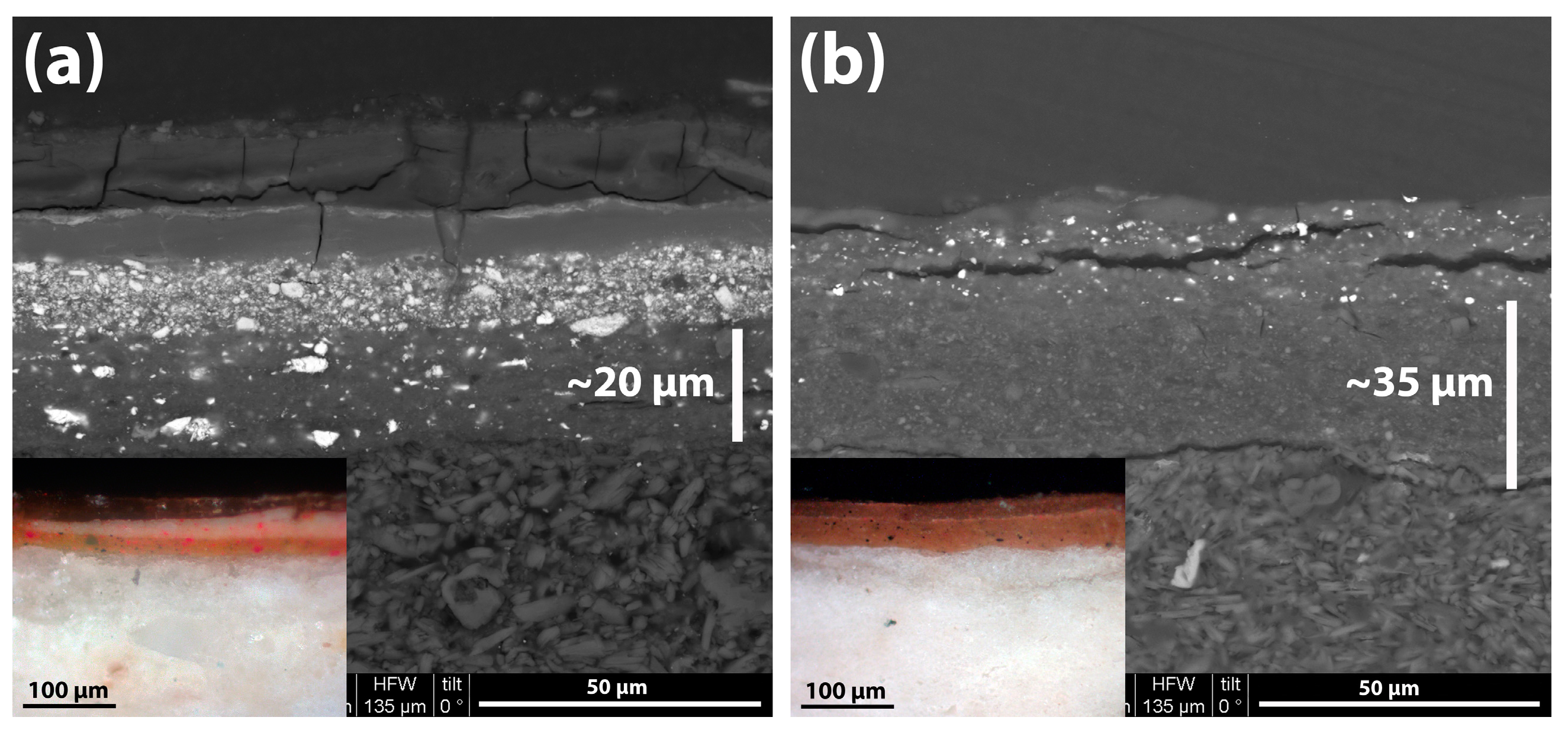

3.2. Ground/Gesso

3.3. Paint Layers

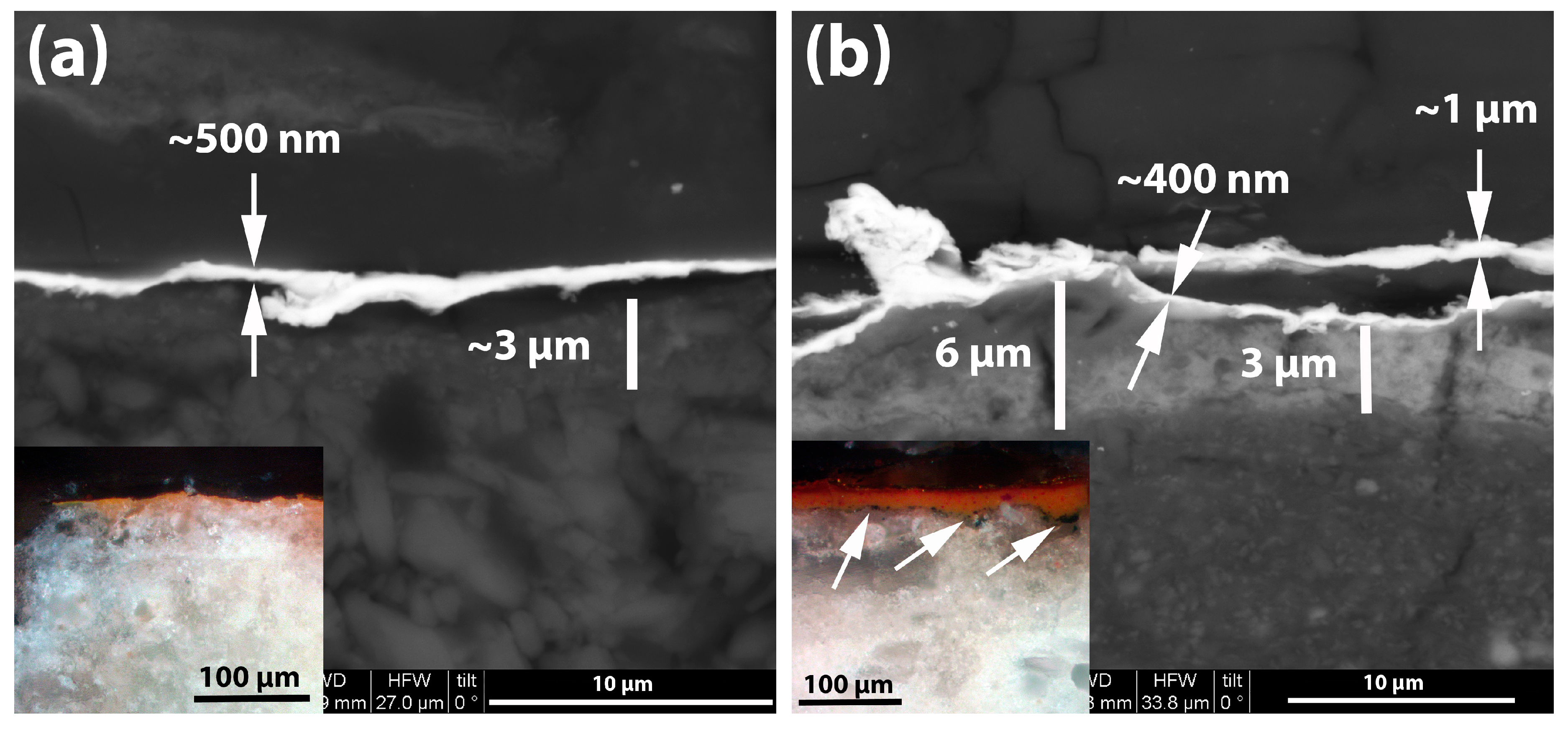

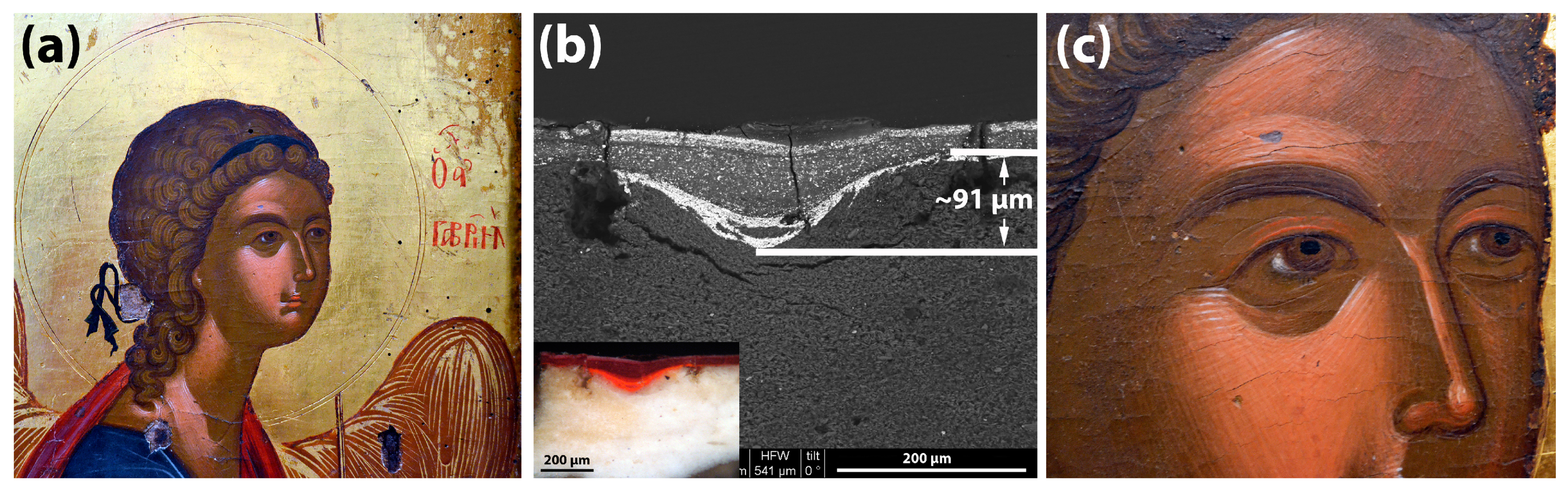

3.4. Gilded Pictorial Elements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vokotopoulos, P. Byzantine Icons; Ekdotiki Athinon: Athens, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Χατζηδάκης, M. Έλληνες ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450–1830) [Greek Painters After the Fall of Constantinople (1450–1830)]; Kentro Neoellinikon Ereunon: Athens, Greece, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Μανουσακας, Μ. Η διαθήκη του Αγγέλου Ακοτάντου (1436), αγνώστου κρητικού ζωγράφου (πίν.52-53). Δελτίον Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας 1962, 20, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cattapan, M. I pittori Pavia, Rizo, Zafuri da Candia e Papadopulo dalla Canea. Thesaurismata 1977, 14, 199–238. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, M. The Painter Angelos and Icon-Painting in Venetian Crete; Ashgate/Variorum: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, M. The Hand of Angelos: An Icon Painter in Venetian Crete; Lund Humphries: Farnham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Μυλωνά, Ζ. Μουσείου Εκκλησιαστικής Τέχνης Ιεράς Μονής Στροφάδων και Αγίου Διονυσίου [Museum of Ecclesiastical Art of the Holy Monastery of Strofades and Saint Dionysius]; Αποστολική Διακονία της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος: Athens, Greece, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Αχειμάστου-Ποταμιάνου, M. Εικόνες της Ζακύνθου [Icons of Zakynthos]; Ιερά Μητρόπολη Ζακύνθου και Στροφάδων: Athens, Greece, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ζήβας, Δ.Α. Ζάκυνθος 1953–2003 [Zakynthos 1953–2003]; Περίπλους: Athens, Greece, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Milanou, K.; Vourvopoulou, C.; Vranopoulou, L.; Kalliga, A.E. Angelos painting technique. A description of panel construction, materials and painting method based on a study of seven signed icons. In Icons by the Hand of Angelos: The Painting Method of a Fifteenth-Century Cretan Painter; Milanou, K., Vourvopoulou, C., Vranopoulou, L., Kalliga, A.E., Eds.; Benaki Museum: Athens, Greece, 2008; pp. 19–114. [Google Scholar]

- Daniilia, S.; Minopoulou, E.; Andrikopoulos, K.S.; Karapanagiotis, I. Analysis of organic and inorganic materials and their application on icons by Angelos. In Icons by the Hand of Angelos: The Painting Method of a Fifteenth-Century Cretan Painter; Milanou, K., Vourvopoulou, C., Vranopoulou, L., Kalliga, A.E., Eds.; Benaki Museum: Athens, Greece, 2008; pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou, A.; Kaminari, A. Study and documentation of an icon of Saint George by Angelos using infrared reflectography. In Icons by the Hand of Angelos: The Painting Method of a Fifteenth-Century Cretan Painter; Milanou, K., Vourvopoulou, C., Vranopoulou, L., Kalliga, A.E., Eds.; Benaki Museum: Athens, Greece, 2008; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Milanou, K.; Vourvopoulou, C.; Vranopoulou, L.; Kalliga, A.E. A technological examination of Cretan icons dating from the end of the 14th to the middle of the 15th century. Μουσείο Μπενάκη 2016, 13–14, 251–272, (In Greek, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Μιλάνου, K.; Βουρβοπούλου, Χ.; Βρανοπούλου, Λ.; Καλλιγά, Α. Ο άγιος Νικόλαος με υπογραφή ‘Χειρ Αγγέλου’. Παρατηρήσεις σχετικές με τα υλικά κατασκευής και την τεχνική του έργου [Saint Nikolaos (icon) signed ‘By the hand of Angelos’. Observations on the materials and techniques of the artifact]. In Χ.Α.Ε. 28ο Συμπόσιο Βυζαντινής και Μεταβυζαντινής Αρχαιολογίας και Τέχνης; Simmetria: Athens, Greece, 2008; pp. 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Stassinopoulos, S. An icon of St Nicolaos with scenes from his life by the painter Angelos. Conservation and technical analysis. Μουσείο Μπενάκη 2016, 13–14, 223–250, (In Greek, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, K.F.J. Strategies of electron probe data reduction. In Electron Probe Quantitation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dionysios of Fourna. The “Painter’s Manual” of Dionysius of Fourna: An English Translation [from the Greek] with Commentary of cod. gr. 708 in the Saltykov-Shchedrin State Public Library, Leningrad; Oakwood: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, A. Infrared technical photography for art examination. e-PRESERVATION Sci. 2016, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, J.R.J.V.A.D. Infrared Reflectography: A Method for the Examination of Paintings. Appl. Opt. 1968, 7, 1711–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, A. Identification of pigments by multispectral imaging; a flowchart method. Heritage Sci. 2014, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.; Schilling, M.R.; Thirkettle, S. A Note on the Use of False-Color Infrared Photography in Conservation. Stud. Conserv. 1992, 37, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, L.P.; Prasad, P.S.R.; Ravikumar, N. Raman Spectroscopic Study of Phase Transitions in Natural Gypsum. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1998, 29, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osticioli, I.; Mendes, N.; Nevin, A.; Gil, F.P.; Becucci, M.; Castellucci, E. Analysis of natural and artificial ultramarine blue pigments using laser induced breakdown and pulsed Raman spectroscopy, statistical analysis and light microscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 73, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesters, J. Ultramarine blue, natural and artificial. In Artist’s Pigments, Vol. 2; Ashok Roy, Ed.; National Gallery of Art: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, I.M.; Clark, R.J.; Gibbs, P.J. Raman spectroscopic library of natural and synthetic pigments (pre- ≈ 1850 AD). Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1997, 53, 2159–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L.; Clark, R.J.H. Library of FT-Raman spectra of pigments, minerals, pigment media and varnishes, and supplement to existing library of Raman spectra of pigments with visible excitation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 57, 1491–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiani, M.; Cosentino, A.; Mangone, A. Pigments Checker version 3.0, a handy set for conservation scientists: A free online Raman spectra database. Microchem. J. 2016, 129, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, C.A. Green earth. In Artists Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; Feller, R.L., Ed.; National Gallery of Art: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y. On the blue and green pigments of post-Byzantine Greek icons. Archaeometry 2020, 62, 774–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticelli, M.; Maras, A.; Candeias, A. μ-Raman as a fundamental tool in the origin of natural or synthetic cinnabar: Preliminary data. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2019, 51, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapanagiotis, I.; Lampakis, D.; Konstanta, A.; Farmakalidis, H. Identification of colourants in icons of the Cretan School of iconography using Raman spectroscopy and liquid chromatography. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J.; Spring, M.; Higgitt, C.; National Gallery. The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate. Available online: www.nationalgallery.co.uk (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Tomasini, E.; Siracusano, G.; Maier, M. Spectroscopic, morphological and chemical characterization of historic pigments based on carbon. Paths for the identification of an artistic pigment. Microchem. J. 2012, 102, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mactaggart, P.; Mactaggart, A. Practical Gilding; Archetype: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y.; Papadopoulou, V. On the Metal-Leaf Decorations of Post-Byzantine Greek Icons. Archaeometry 2017, 60, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Anagnostopoulos, D.F.; Beltsios, K.G.; Filippaki, E.; Bassiakos, Y. Glittering on the Wall: Gildings on Greek Post-Byzantine Wall Paintings. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 962, pp. 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valianou, L.; Wei, S.; Mubarak, M.S.; Farmakalidis, H.; Rosenberg, E.; Stassinopoulos, S.; Karapanagiotis, I. Identification of organic materials in icons of the Cretan School of iconography. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapanagiotis, I.; Minopoulou, E.; Valianou, L.; Daniilia, S.; Chryssoulakis, Y. Investigation of the colourants used in icons of the Cretan School of iconography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 647, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P. Pigments and Various Materials of Post-Byzantine Painting. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G.; Bassiakos, Y.; Papadopoulou, V. On the Grounds of Post-Byzantine Greek Icons. Archaeometry 2015, 58, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennini, C. The Craftsman’s Handbook; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G. Sound Practice and Practical Conservation Recipes as Described in Greek Post-Byzantine Painters’ Manuals. Stud. Conserv. 2018, 64, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase/Pigment | EDX Analysis Results (Elements, wt%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | Mg | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | Ca | Fe | Pb | Other | Grain Size (μm) | |

| Gesso/ground | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 38.8 | 58.3 | n.d. | |||||

| Lazurite | 13.5 | 21.9 | 39.0 | 14.8 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 8.1 | 4–22 | ||||

| Green earth | 5.1 | 2.9 | 45.2 | 1.3 | 12.5 | 4.3 | 28.7 | 6–23 | ||||

| Red lake | 1.6 | 1.4 | 44.1 | 6.8 | 10.5 | 9.2 | 4.0 | 15.9 | 2.4 | P (4.1) | n.d. | |

| Red iron ochre | 2.1 | 9.1 | 16.5 | 6.1 | 1.0 | 15.7 | 45.9 | P (3.6) | 4–5 | |||

| Cinnabar | 14.7 | Hg (85.3) | 0.8–7.0 | |||||||||

| Orange iron ochre | 0.5 | 1.3 | 17.9 | 34.5 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 8.7 | 29.5 | P/Ti (1.4/0.2) | 1–5 | |

| Lead white | 100.0 | 0.4–8.0 | ||||||||||

| Minium | 100.0 | 2–9 | ||||||||||

| Charcoal | ~0.5–2.0 | |||||||||||

| Gold leaf adhesives | ||||||||||||

| Na | Mg | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | Ca | Fe | Pb | Other | Layer thickness (μm) | |

| Yellow bole (campus) | 0.4 | 1.4 | 18.3 | 35.1 | 5.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 13.6 | 22.8 | Ti (0.3) | 3–8 | |

| Mordant (highlights) | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 13.0 | 4.0 | 65.8 | P (3.8) | 2.5–7.0 | |

| Gold leaves | ||||||||||||

| Spot | EDX (elements wt%) | Leaf Thickness (μm) | ||||||||||

| Ag | Cu | Au | ||||||||||

| Background/“campus” | 0.1 | 0.3 | 99.6 | ~0.4–0.6 | ||||||||

| Gilded highlights on vestments | 0.0 | 0.3 | 99.7 | ~0.4–0.6 | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Theodosis, M.; Filippaki, E.; Beltsios, K.G. By the Hand of Angelos? Analytical Investigation of a Remarkable 15th Century Cretan Icon. Heritage 2020, 3, 1360-1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040075

Mastrotheodoros GP, Theodosis M, Filippaki E, Beltsios KG. By the Hand of Angelos? Analytical Investigation of a Remarkable 15th Century Cretan Icon. Heritage. 2020; 3(4):1360-1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleMastrotheodoros, Georgios P., Marios Theodosis, Eleni Filippaki, and Konstantinos G. Beltsios. 2020. "By the Hand of Angelos? Analytical Investigation of a Remarkable 15th Century Cretan Icon" Heritage 3, no. 4: 1360-1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040075

APA StyleMastrotheodoros, G. P., Theodosis, M., Filippaki, E., & Beltsios, K. G. (2020). By the Hand of Angelos? Analytical Investigation of a Remarkable 15th Century Cretan Icon. Heritage, 3(4), 1360-1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3040075