Biological Profile Estimation Based on Footprints and Shoeprints from Bracara Augusta Figlinae (Brick Workshops)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sample

3. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, T.D.; Black, M.T.; Folkens, P.A. Human Osteology, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Novotný, V.; Isçan, M.Y.; Loth, S.R. Morphologic and osteometric assessment of age, sex, and race from the skull. In Forensic Analysis of the Skull; Isçan, M.Y., Helmer, R.P., Eds.; Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hemy, N.; Flavel, A.; Ishak, N.-I.; Franklin, D. Estimation of stature using anthropometry of feet and footprints in a Western Australian population. J. Forensic Legal Med. 2013, 20, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastoors, A.; Lenssen-Erz, T.; Breuckmann, B.; Ciqae, T.; Kxunta, U.; Rieke-Zapp, D.; Thao, T. Experience based reading of Pleistocene human footprints in Pech-Merle. Quat. Int. 2017, 430, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Martins, M. História e arqueologia de uma cidade em devir: Bracara Augusta. Cad. Arqueol. 1989, 6–7, 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.; Ribeiro, J.; Magalhães, F.; Braga, C. Urbanismo e arquitetura de Bracara Augusta. Sociedade, economia e lazer. In Evolução da Paisagem Urbana: Sociedade e Economia; Ribeiro, M.D.C., Melo, A., Eds.; CITCEM: Porto, Portugal, 2012; pp. 29–68. ISBN 978-989-97558-7-1. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Blais, M.; Green, W.T. Growth of the normal foot during childhood and adolescence: Length of the foot and interrelations of foot, stature, and lower extremity as seen in serial records of children between 1–18 years of age. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1956, 14, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivas, T.B.; Mihas, C.; Arapaki, A.; Vasiliadis, E. Correlation of foot length with height and weight in school age children. J. Forensic Legal Med. 2008, 15, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozden, H.; Balci, Y.; Demirüstü, C.; Turgut, A.; Ertugrul, M. Stature and sex estimate using foot and shoe dimensions. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 147, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atamturk, D. Estimation of Sex from the Dimensions of Foot, Footprints, and Shoe. Anthropol. Anz. 2010, 68, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, I.A.; Kamal, N.N. Stature and Body Weight Estimation from Various Footprint Measurements Among Egyptian Population. J. Forensic Sci. 2010, 55, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reel, S.; Rouse, S.; Vernon, W.; Doherty, P. Estimation of stature from static and dynamic footprints. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 219, 283.e1–283.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhrová, P.; Beňuš, R.; Masnicová, S. Stature Estimation from Various Foot Dimensions Among Slovak Population. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasuja, O.P.; Singh, J.; Jain, M. Estimation of stature from foot and shoe measurements by multiplication factors: A revised attempt. Forensic Sci. Int. 1991, 50, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masao, F.T.; Ichumbaki, E.B.; Cherin, M.; Barili, A.; Boschian, G.; Iurino, D.A.; Menconero, S.; Moggi-Cecchi, J.; Manzi, G. New footprints from Laetoli (Tanzania) provide evidence for marked body size variation in early hominins. Elife 2016, 5, e19568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingwall, H.L.; Hatala, K.G.; Wunderlich, R.E.; Richmond, B.G. Hominin stature, body mass, and walking speed estimates based on 1.5 million-year-old fossil footprints at Ileret, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 2013, 64, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, N.; Lewis, S.G.; De Groote, I.; Duffy, S.M.; Bates, M.; Bates, R.; Hoare, P.; Lewis, M.; Parfitt, S.A.; Peglar, S.; et al. Hominin footprints from Early Pleistocene deposits at Happisburgh, UK. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Webb, S.; Cupper, M.L.; Robins, R. Pleistocene human footprints from the Willandra Lakes, southeastern Australia. J. Hum. Evol. 2006, 50, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockley, M.G.; Garcia-Vasquez, R.; Espinoza, E.; Lucas, S.G. Notes on a famous but “forgotten” human footprint site from the Holocene of Nicaragua. N. M. Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. Bull. 2007, 42, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, P.J.; Kennedy, M.C.; Willey, P.; Robbins, L.M.; Wilson, R.C. Prehistoric Footprints in Jaguar Cave, Tennessee. J. F. Archaeol. 2005, 30, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdière, A. La production de terres cuites architecturales en Gaule et dans l’Occident romain, à la lumière de l’exemple de la Lyonnaise et des cités du nord-est de l’Aquitaine: Un artisanat rural de caractère domanial? Rev. Archeol. Centre Fr. 2012, 51, 17–187. [Google Scholar]

- Fessler, D.M.T.; Haley, K.J.; Lal, R.D. Sexual dimorphism in foot length proportionate to stature. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2005, 32, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, C.B. The growth of the human foot. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1932, 17, 167–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, H.V. Human foot length from embryo to adult. Hum. Biol. 1944, 16, 207–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cram, L. Empreintes sur des tuiles romaines. Les Doss. Hist. Archéol. 1985, 90, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Goulpeau, L.; Le Ny, F. Les marques digitées apposées sur les matériaux de construction gallo-romains en argile cuite. Rev. Archéol. l’ouest 1989, 6, 105–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, H.F.V.; Gomes, J.E.A. Trends in Adult Stature of Peoples who Inhabited the Modern Portuguese Territory from the Mesolithic to the Late 20th Century. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2009, 19, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Quintana-Domeque, C. The evolution of adult height in Europe: A brief note. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2007, 5, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeybek, G.; Ergur, I.; Demiroglu, Z. Stature and gender estimation using foot measurements. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atamturk, D.; Ozbal, R.; Gerritsen, F.; Duyar, I. Analysis and interpretation of Neolithic period footprints from Barcın Höyük, Turkey. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2018, 18, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

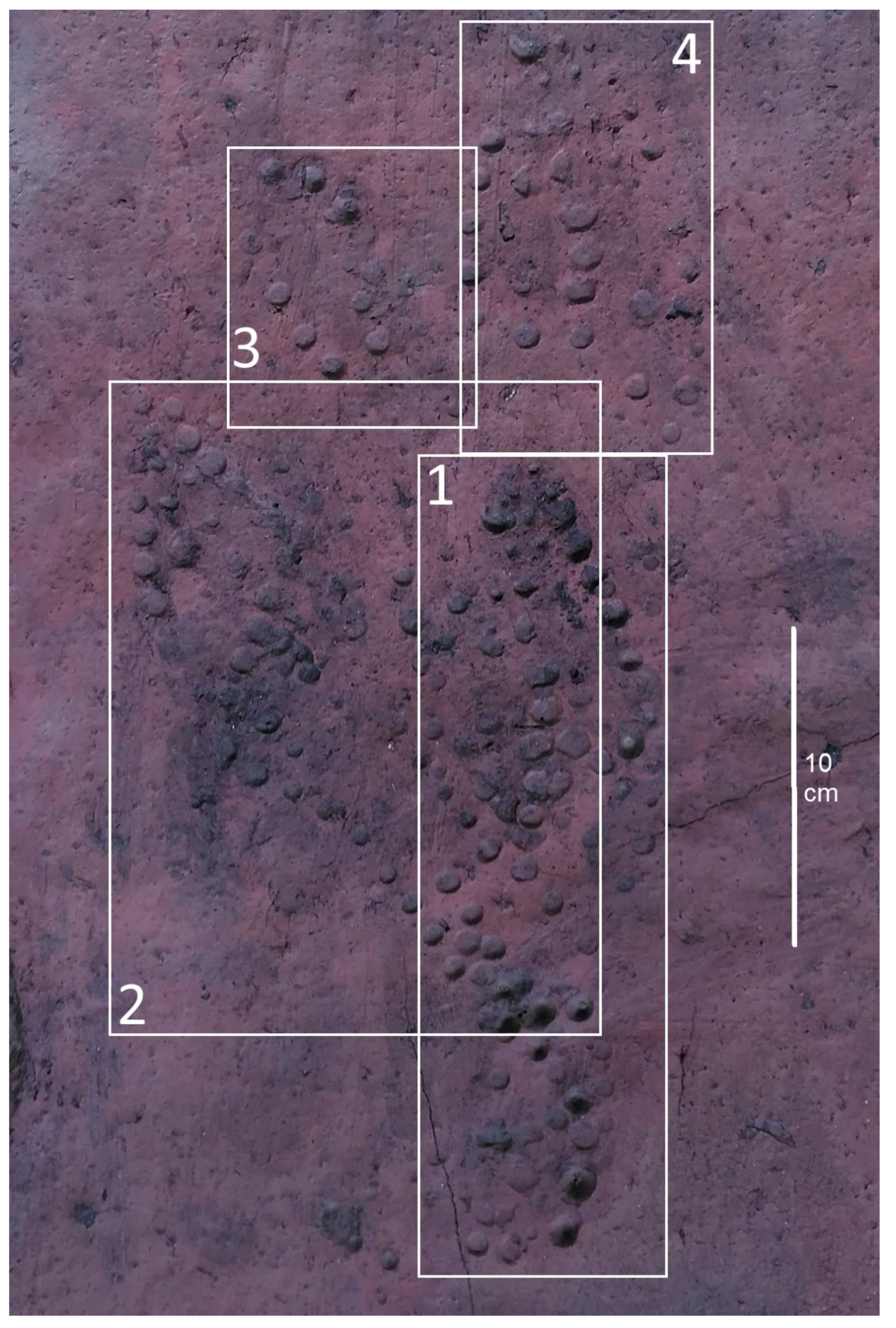

| Inventory | Brick Type | Print Type (n) | Dimensions (mm) | Context | Chronology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001.1281 | Pedale/lydion | Foot (3) | 238 × 291 × 37 | Colina Roman baths (?) | Unknown |

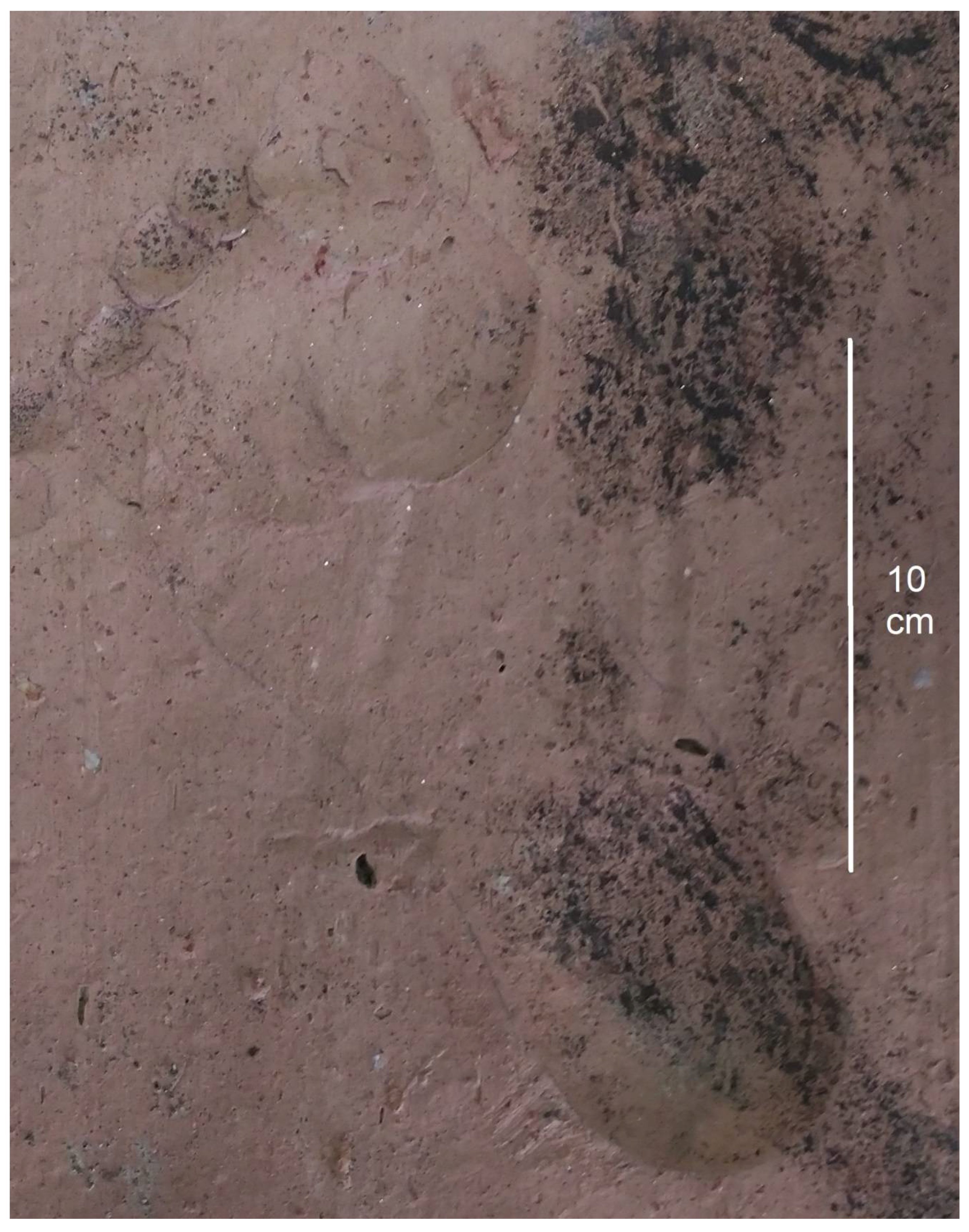

| 2001.1280 | Pedale derivation; Cuneati | Foot (1) | 335 × 256 to 274 × 91 | Cavalariças domus’ mosaic | Earlier than 3rd c. |

| 2004.1119 | Lydion derivation | Foot (1) | 404 × 290 × 38 | Misericórdia necropolis | Late Antiquity |

| 1995.0065 | Vault brick | Sandal (2) | 150 × 285 × 41 | Colina Roman baths | Earlier than 5th c. |

| 1994.0492 | Pedale/lydion | Sandal (1) | 275 × 288 × 55 | Albergue domus | Later than 1st c. |

| R25A | Bipedale derivation | Sandal (4) | 560 × 490 × 50 | R. 25 de Abril (Via XVII) necropolis | 4th c. (under study) |

| Method | Estimates | Measures | Origin | Size (n) | Age (Years) | Distance to Braga (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Non-adult age | Foot | Boston, Massachussets | 532 (F + M) | 1 to 18 | 5060 |

| [8] | Non-adult stature and weight | Foot | Elefsina, Greece | 5254 (F + M) | 5.5 to 20 | 2743 |

| [9] | Adult sex | Foot & shoe | Eskisehir University, Turkey | 275 F + 294 M | 19 to 77 | 3263 |

| [10] | Adult sex | Footprint & shoe | Ankara, Turkey | 253 F + 253 M | 17.6 to 82.9 | 3450 |

| [3] | Adult sex | Footprint | Western Australia | 110 F + 90 M | 18 to 68 | 15,134 |

| [11] | Adult stature and weight | Footprint | El Minia University, Egypt | 50 M | 18 to 25 | 3837 |

| [12] | Adult stature | Mobile & static footprints | UK | 30 F + 31 M | Mean = 40 | 1500 |

| [13] | Adult stature | Foot | Comenius University, Slovakia | 38 F + 33 M | 18 to 27 | 2128 |

| [14] | Adult stature | Shoe (& foot) | Jat Sikhs, Patiala, India | 256 M | Adults | 7434 |

| Footprint Measurements | 2001.1281 #1 | 2001.1281 #2 | 2001.1281 #3 | 2001.1280 | 2004.1119 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 162 | 106 | NO | 215 | 211 | ||

| 2 | NO | NO | NO | 209 | 207 | ||

| 3 | NO | NO | NO | 199 | 202 | ||

| 4 | NO | NO | NO | 185 | 192 | ||

| 5 | NO | NO | NO | 175 | NO | ||

| 6 | 67 | 64 | 58 | 103 | 100 | ||

| 7 | 53 | 50 | 47 | 85 | 87 | ||

| 8 | 41 | NO | NO | 51 | 52 | ||

| 9 | 40 | 28 | NO | 46 | 51 | ||

| 10 | 42 | 30 | NO | 51 | 53 | ||

| Shoeprint measurements | 1995.0065 #1 | 1995.0065 #2 | 1994.0492 | R25A #1 | R25A #2 | R25A #3 | R25A #4 |

| 11 | NO | NO | 238 (245 *) | 245 | 230 | NO | NO |

| 12 | NO | NO | 78 | 70 | 61 | NO | NO |

| Sex | Print Type | Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001.1281 #1 | NO (non-adult) | Left foot | - |

| 2001.1281 #2 | NO (non-adult) | Left foot | |

| 2001.1281 #3 | NO (non-adult) | Left foot | |

| 2001.1280 | Female | Right foot | [3,9,10] |

| 2004.1119 | Female | Left foot | |

| 1995.0065 #1 | NO (partial) | Sandal | - |

| 1995.0065 #2 | NO (partial) | Sandal | |

| 1994.0492 | Female | Left sandal | [9,10] |

| R25A #1 | Female | Right sandal | |

| R25A #2 | Female | Left sandal | |

| R25A #3 | NO (partial) | Sandal | - |

| R25A #4 | NO (partial) | Sandal |

| Age (Years) | Print Type | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001.1281 #1 | 4–5 | Left foot | [7] |

| 2001.1281 #2 | 1 | Left foot | |

| 2001.1281 #3 | 1 (?) | Left foot | |

| 2001.1280 | Adult | Right foot | |

| 2004.1119 | Adult | Left foot | |

| 1995.0065 #1 | NO (partial) | Sandal | |

| 1995.0065 #2 | NO (partial) | Sandal | |

| 1994.0492 | Adult | Left sandal | |

| R25A #1 | Adult | Right sandal | |

| R25A #2 | Adult | Left sandal | |

| R25A #3 | NO (partial) | Sandal | |

| R25A #4 | NO (partial) | Sandal |

| Stature (cm) | Print Type | Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001.1281 #1 | 112.5 ± 7.7 | Left foot | [8] |

| 2001.1281 #2 | 79.7 ± 7.7 | Left foot | |

| 2001.1281 #3 | NO (partial) | Left foot | - |

| 2001.1280 | 157.7 ± 3.5 | Right foot | [11] |

| 159.9 ± 4.2 | [12] | ||

| 155.7 ± 4.7 | [13] | ||

| 2004.1119 | 156.9 ± 3.6 | Left foot | [11] |

| 155.6 ± 5.2 | [12] | ||

| 153.3 ± 4.8 | [13] | ||

| 1995.0065 #1 | NO (partial) | Sandal | - |

| 1995.0065 #2 | NO (partial) | Sandal | |

| 1994.0492 | 155.5 ± 4.8 | Left sandal | [14] |

| R25A #1 | 155.1 ± 3.6 | Right sandal | |

| R25A #2 | 144.2 ± 3.9 | Left sandal | |

| R25A #3 | NO (partial) | Sandal | - |

| R25A #4 | NO (partial) | Sandal |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marado, L.M.; Ribeiro, J. Biological Profile Estimation Based on Footprints and Shoeprints from Bracara Augusta Figlinae (Brick Workshops). Heritage 2018, 1, 33-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage1010003

Marado LM, Ribeiro J. Biological Profile Estimation Based on Footprints and Shoeprints from Bracara Augusta Figlinae (Brick Workshops). Heritage. 2018; 1(1):33-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarado, Luís Miguel, and Jorge Ribeiro. 2018. "Biological Profile Estimation Based on Footprints and Shoeprints from Bracara Augusta Figlinae (Brick Workshops)" Heritage 1, no. 1: 33-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage1010003

APA StyleMarado, L. M., & Ribeiro, J. (2018). Biological Profile Estimation Based on Footprints and Shoeprints from Bracara Augusta Figlinae (Brick Workshops). Heritage, 1(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage1010003