Smarter Chains, Safer Medicines: From Predictive Failures to Algorithmic Fixes in Global Pharmaceutical Logistics

Highlights

- Gradient boosting achieved the highest accuracy in pricing prediction ( = 0.7610), while ARIMA delivered the lowest demand-forecasting RMSE (0.0758) and LSTM provided the strongest neural network performance for volatile demand swings.

- The novel PCA–K-Means vendor segmentation identified three performance clusters: high-performing, cost-efficient, and mixed vendors, enabling strategic supply chain optimization and up to 15–25% reduction in logistics costs.

- Pharmaceutical companies can integrate these AI/ML models to enhance operational efficiency, reduce stockouts and holding costs, and improve decision-making in areas such as pricing, balancing supply and demand, and vendor management.

- The study establishes empirical benchmarks and best practices for applying AI in pharmaceutical logistics, demonstrating how data-driven modeling can strengthen supply chain resilience and inform future AI governance in healthcare.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Research Questions:

- How do different AI and ML techniques compare in their effectiveness for pharmaceutical demand forecasting?

- Which computational models provide the most accurate pricing predictions for pharmaceutical products?

- How can vendor performance be systematically evaluated and segmented using ML approaches?

- What are the optimal shipment mode selection strategies for pharmaceutical logistics?

- How can maintenance needs be predicted to minimize delivery delays in pharmaceutical supply chains?

2. Medicine Procurement, Manufacturing and Dispatching

2.1. Advanced and Initial AI and ML in the Pharmaceutical Sector

2.2. Predictive Failure Detection and Resolution of Underlying Inefficiencies

2.3. Accelerating AI Adoption, Demand Prediction, and Drug Delivery

2.4. Supplier Selection, Security, Cost Prediction, and Supply Chain Optimization

2.5. Lead Time Forecasting, Inventory Management, and Optimization Algorithms

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Mathematical Framework and Model Specifications

3.1.1. Time Series Forecasting Models

3.1.2. Ensemble Methods

3.1.3. Clustering and Dimensionality Reduction

3.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

3.1.5. Model Parameters and Validation Procedures

4. Results: Analysis of Machine Learning Models in Optimizing Pharmaceutical Logistics

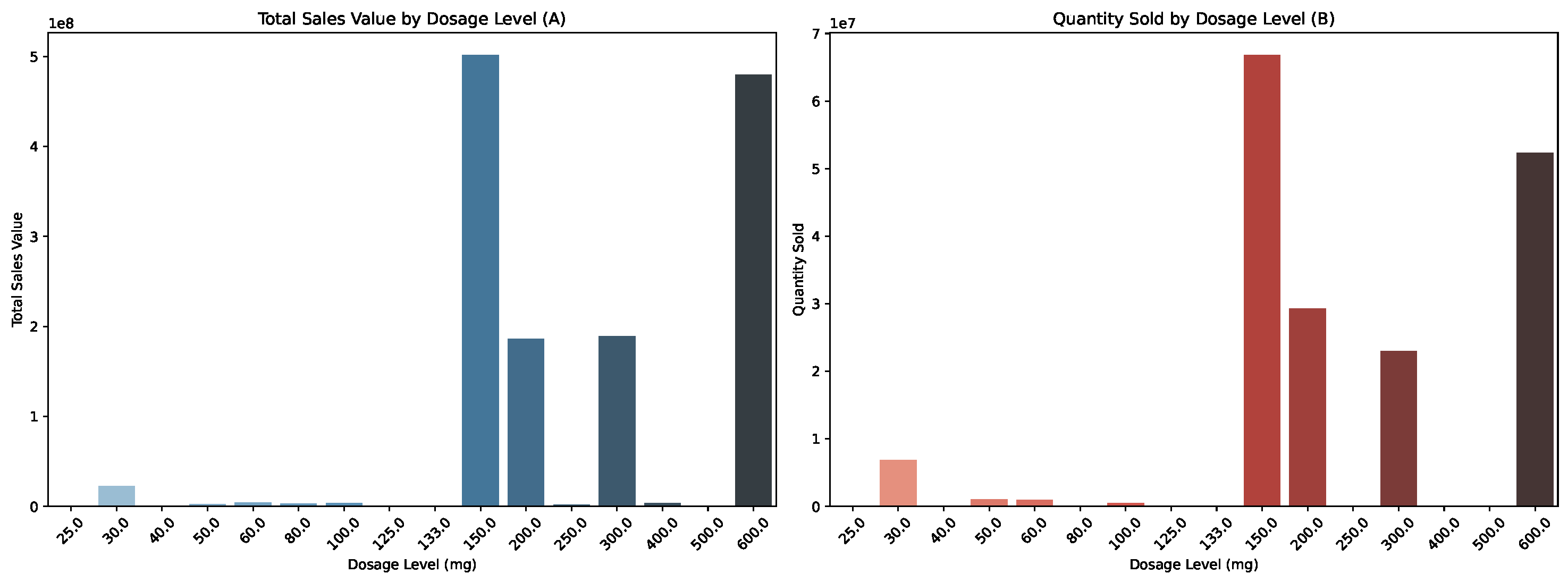

4.1. Pricing Prediction

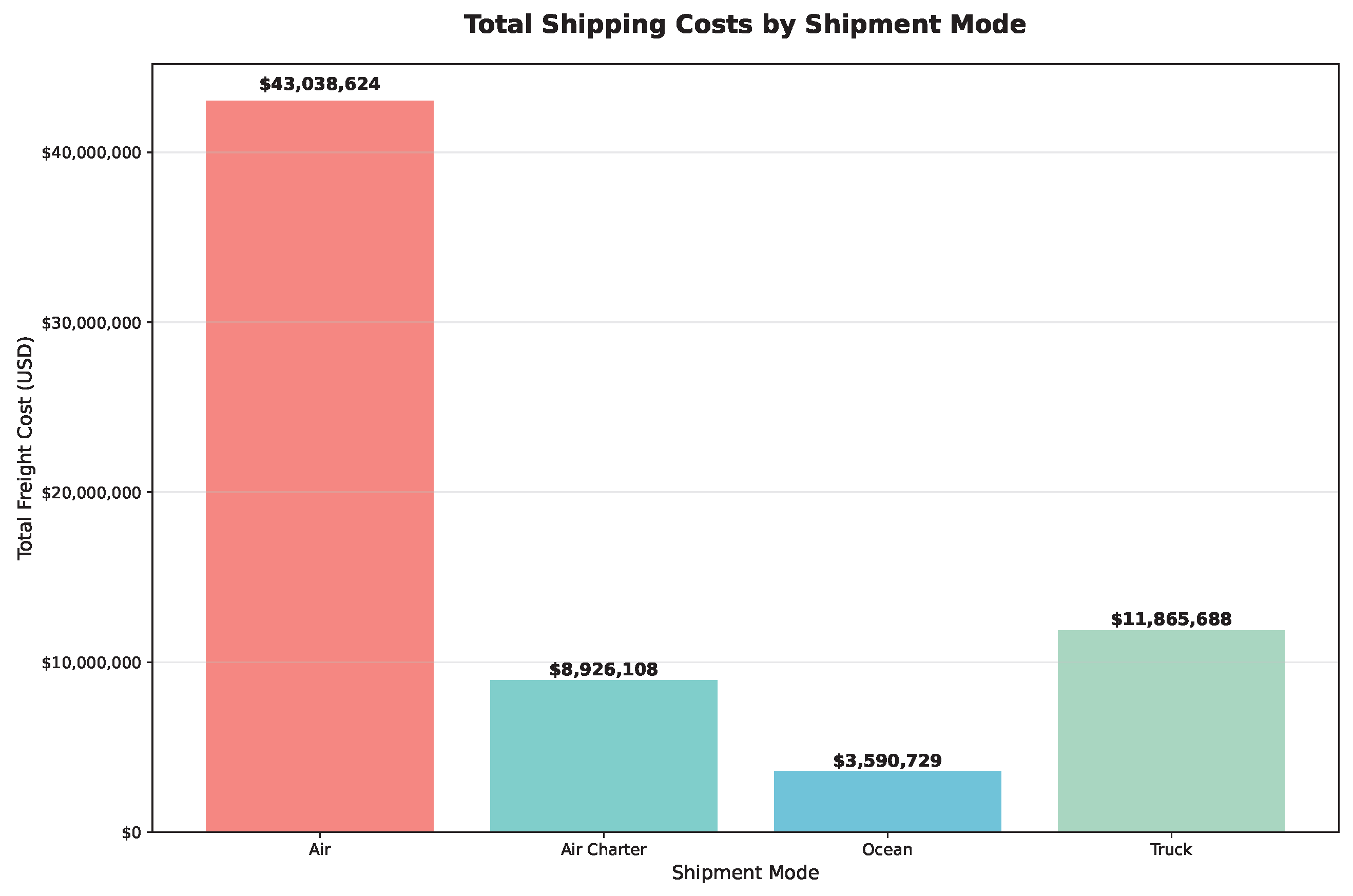

4.2. Forecasting Demand and Identifying Cost-Effective Shipment Modes

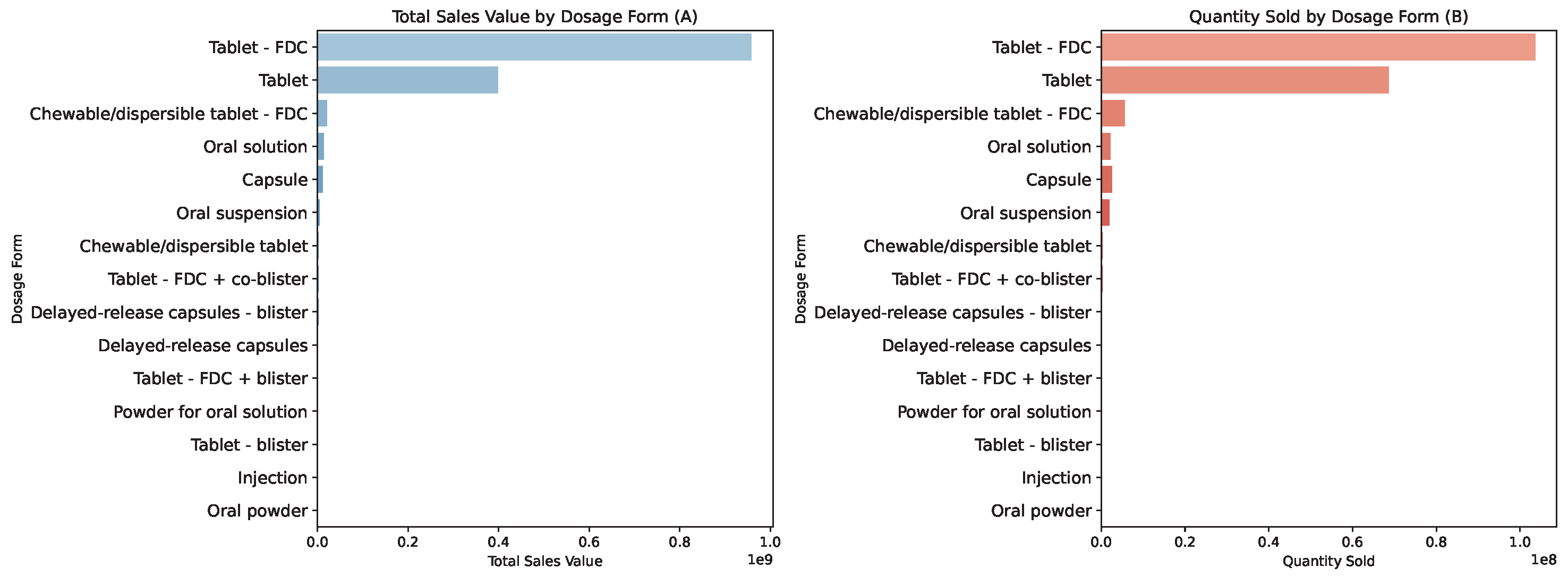

4.2.1. Meeting Demand and Managing Costs

4.2.2. Analyzing Delivery Performance and Cost Efficiency Across Shipment Modes and Countries

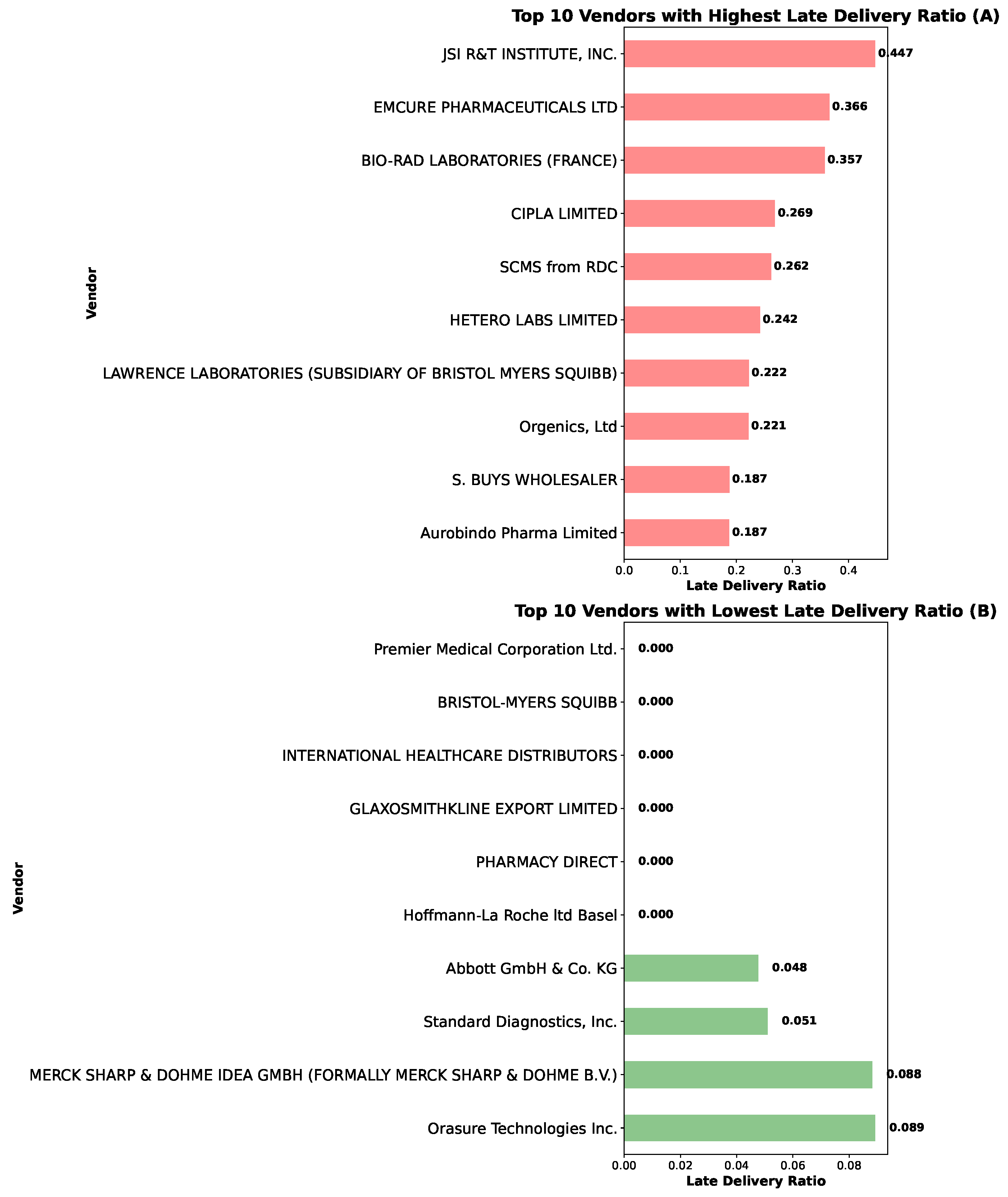

4.3. Vendor Management

4.3.1. Vendor Delivery Performance Evaluation

4.3.2. Relationship Between Shipment Status and Delay: Vendor Analysis

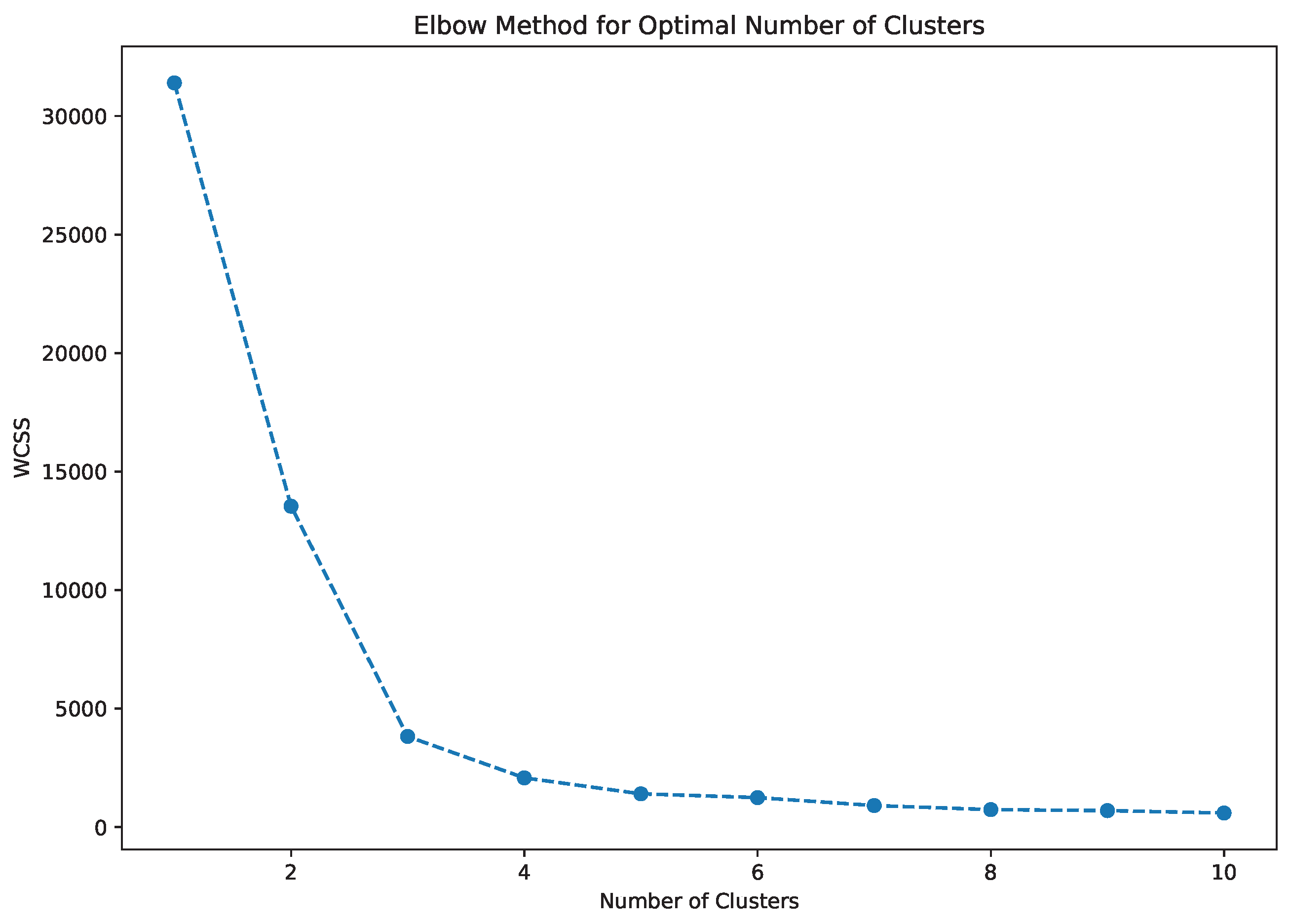

4.4. VendorSegmentation Using PCA and K-Means Clustering

4.5. Logistical Bottlenecks, Maintenance Needs, and Delivery Delays

4.6. Managerial Interpretation of Results

5. Contributions, Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moosivand, A.; Ghatari, A.R.; Rasekh, H.R. Supply Chain Challenges in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Companies: Using Qualitative System Dynamics Methodology. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gonzalez, A.; Cabezon, A.; Seco-Gonzalez, A.; Conde-Torres, D.; Antelo-Riveiro, P.; Pineiro, A.; Garcia-Fandino, R. The role of AI in drug discovery: Challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 16, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, L.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Jetha, K.; Thakur, R.R.S.; Solanki, H.K.; Chavda, V.P. Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Technology and Drug Delivery Design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaku, E.A.; Edunjobi, T.E.; Odimarha, A.C. Theoretical approaches to AI in supply chain optimization: Pathways to efficiency and resilience. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. Arch. 2024, 6, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angula, T.N.; Dongo, A. Assessing the impact of artificial intelligence and machine learning on forecasting medication demand and supply in public pharmaceutical systems: A systematic review. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 26, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez del Rio, A.; Leong, M.B.; Saraiva, P.; Nazarov, I.; Rastogi, A.; Hassan, M.; Tang, D.; Perianez, A. Adaptive behavioral AI: Reinforcement learning to enhance pharmacy services. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mani, V.; Jain, V.; Gupta, H.; Venkatesh, V.G. Managing healthcare supply chain through artificial intelligence (AI): A study of critical success factors. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 175, 108815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhich, A.; Dadhich, P. Artificial intelligence from vaccine development to pharmaceutical supply chain management in post-COVID-19 period. In AI for Supply Chain Management; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, G.; Gould, A.M.; Park, K. Sizzle without the steak: The emerging strategic implications of receiving a free offering in the digital age. J. Manag. Hist. 2023, 29, 608–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.D.; Baral, S.K.; Pitke, M.; Dwyer, R.J. Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Healthcare: India Retrospective. In Analyzing Current Digital Healthcare Trends Using Social Networks; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Peelam, M.S.; Chauasia, B.K.; Chamola, V. QIoTChain: Quantum IoT-blockchain fusion for advanced data protection in Industry 4.0. IET Blockchain 2023, 4, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.S.; Banerjee, D.N. Omission and commission errors underlying AI failures. AI Soc. 2024, 39, 937–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westenberger, J.; Schuler, K.; Schlegel, D. Failure of AI projects: Understanding the critical factors. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 196, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.P.; Saw, P.S.; Jomthanachai, S.; Wang, L.S.; Ong, H.F.; Lim, C.P. Digitalization enhancement in the pharmaceutical supply network using a supply chain risk management approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yampolskiy, R.V. Artificial Intelligence Safety and Cybersecurity: A Timeline of AI Failures. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.07997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, W.J.; de Oliveira Santini, F.; da Costa, J.R.A.; Ribeiro, L.E.S. Strategic orientation for failure recovery and performance behavior. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yampolskiy, R.V. Predicting future AI failures from historic examples. Foresight 2019, 21, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Kaushik, A.; Yadav, N. Predicting machine failures using machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2024, 3, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Yampolskiy, R. Understanding and Avoiding AI Failures: A Practical Guide. Philosophies 2021, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Sun, Z.; Fu, S.; Lv, Y. Human-AI interaction research agenda: A user-centered perspective. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 8, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbjornrud, V. Designing the Intelligent Organization: Six Principles for Human-AI Collaboration. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2024, 66, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqatan, A.; Simmou, W.; Shehadeh, M.; AlReshaid, F.; Elmarzouky, M.; Shohaieb, D. Strategic Pathways to Corporate Sustainability: The Roles of Transformational Leadership, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviskar, K.; Bedse, A.; Raut, S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-based manufacturing and drug product marketing. In Bioinformatics Tools for Pharmaceutical Drug Product Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathipriya, R.; Rahman, A.A.A.; Dhamodharavadhani, S.; Meero, A.; Yoganandan, G. Demand forecasting model for time-series pharmaceutical data using shallow and deep neural network model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, B.A.; Al-Khateeb, B. Predicting medicine demand using deep learning techniques: A review. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 32, 20220297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabad, S.; Lamkhade, D.; Koyate, S.; Karanjkhele, K.; Kale, V.; Doke, R. Transformative trends: A comprehensive review on role of artificial intelligence in healthcare and pharmaceutical research. IP Int. J. Compr. Adv. Pharmacol. 2023, 8, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atal, D.K.; Tiwari, V.; Anjali; Berwer, R.K. The intersection of blockchain technology and the quantum era for sustainable medical services. In Quantum and Blockchain-Based Next Generation Sustainable Computing; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapatla, A.K.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E.; Puthal, D.; Bapatla, A. PharmaChain: A blockchain to ensure counterfeit-free pharmaceutical supply chain. IET Netw. 2022, 12, 53–76. Available online: https://ietresearch.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1049/ntw2.12041 (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, P.K.; Yadav, A.S.; Arora, T.K.; Ahlawat, N.; Purohit, P.; Swami, A.; Agarwal, P. Machine learning and deep learning based optimization algorithms for COVID-19 pharmaceutical industry supply chain management. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2022, 65, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Hussain, A.; Masood, T.; Habib, M.S. Supply chain operations management in pandemics: A state-of-the-art review inspired by COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modgil, S.; Singh, R.K.; Hannibal, C. Artificial intelligence for supply chain resilience: Learning from COVID-19. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 1246–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, S.; Tausch, A.; Ontrup, G.; Gilles, B.; Peifer, C.; Kluge, A. Defining human-AI teaming the human-centered way: A scoping review and network analysis. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1250725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, M.B.; Devi, K.; Venkataraman, Y.; Lim, M.K.; Theivendren, P. Using AI and ML to predict shipment times of therapeutics, diagnostics and vaccines in e-pharmacy supply chains during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantini, C.; Khan, T.; Mircoli, A.; Potena, D. Forecasting of key performance indicators based on transformer model. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024), Lisbon, Portugal, 26–28 April 2024; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.D.; Edmondson, A.C. Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently): How great organizations put failure to work to innovate and improve. Long Range Plan. 2005, 38, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, W.H.; Hedberg, B. How Organizations Learn from Success and Failure. In Organizational Learning and Knowledge; Dierkes, M., Berthoin Antal, A., Child, J., Nonaka, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedler, L.; Graf-Vlachy, L.; König, A. Strategic leadership in organizational crises: A review and research agenda. Long Range Plan. 2022, 55, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, B.; Jackson, P. Success and failure in organizational change: An exploration of the role of values. J. Chang. Manag. 2011, 11, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G.M.; Bouckenooghe, D. Repositioning Organizational Failure Through Active Acceptance. Organ. Theory 2021, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.; Starr, E.; Agarwal, R. Machine learning and human capital complementarities: Experimental evidence on bias mitigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 1381–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Jia, N.; Ouyang, E.; Fang, Z. Introducing machine-learning-based data fusion methods for analyzing multimodal data: An application of measuring trustworthiness of microenterprises. Strateg. Manag. J. 2024, 45, 1597–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowski, S.; Luger, J.; Raisch, S. Artificial intelligence and the changing sources of competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2023, 44, 1425–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detwal, P.K.; Soni, G.; Jakhar, S.K.; Srivastava, D.K.; Madaan, J.; Kayikci, Y. Machine learning-based technique for predicting vendor Incoterm in global omnichannel pharmaceutical supply chain. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 144, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Awatade, G.V.; Padole, S.S. Digital supply chain management using AI, ML, and blockchain. In Supply Chain Management via Blockchain; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Emary, I.M. Handbook of research on artificial intelligence and soft computing techniques in personalized healthcare services. In Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Commerce and Internet Technology (ECIT), Zhangjiajie, China, 22–24 April 2020; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2020; pp. 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Misra, K.; Dhanuka, R.; Singh, J.P. Artificial intelligence in accelerating drug discovery and development. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2023, 17, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwal, A.; Lavecchia, A. Unlocking the potential of generative AI in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Yoon, H.; Kim, G.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y. Revolutionizing medicinal chemistry: The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in early drug discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala, A.; Goli, A.; Mirjalili, S.; Simic, V. A fuzzy multi-objective optimization model for sustainable healthcare supply chain network design. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 150, 111012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, F.; Ghorbel, A.; Masmoudi, F.; Dupont, L. Optimization of a supply portfolio in the context of supply chain risk management: Literature review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29, 763–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.; Lu, L.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Luo, X. Intelligent selection of healthcare supply chain mode: An applied research based on artificial intelligence. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1310016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thethi, S.K. Machine learning models for cost-effective healthcare delivery systems: A global perspective. In Digital Transformation in Healthcare 5.0: Volume 1: IoT, AI and Digital Twin; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2024; p. 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farchi, F.; Farchi, C.; Touzi, B. A comparative study on AI-based algorithms for cost prediction in pharmaceutical transport logistics. Acadlore Trans. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. 2023, 2, 129–141. Available online: https://library.acadlore.com/ATAIML/2023/2/3/ATAIML_02.03_02.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Farchi, F.; Touzi, B.; Farchi, C.; Mabrouki, C. Machine learning prediction model: A case study of urban transport of medical and pharmaceutical products. Rev. Intelligence Artif. 2024, 38, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomasta, S.S.; Dhali, A.; Tahlil, T.; Anwar, M.M.; Ali, A.B.M.S. PharmaChain: Blockchain-based drug supply chain provenance verification system. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, A.; Alahmadi, A.; Ghose, S.; Mashatan, A. Blockchain platform for industrial healthcare: Vision and future opportunities. Comput. Commun. 2020, 154, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, A. Predictive analytics and machine learning for real-time supply chain risk mitigation and agility. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahrouj, H.; Alghamdi, R.; Alwazani, H.; Bahanshal, S.; Ahmad, A.A.; Faisal, A.; Shamma, J.S.; Alhadrami, R.; Subasi, A.; Al-Nory, M.T.; et al. An overview of machine learning-based techniques for solving optimization problems in communications and signal processing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 74908–74938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ninh, A.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Z. Demand forecasting with supply-chain information and machine learning: Evidence in the pharmaceutical industry. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 3231–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotine, M. Shaping the next generation pharmaceutical supply chain control tower with autonomous intelligence. J. Auton. Intell. 2019, 2, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.I.; Omeke, K.G.; Ozturk, M.; Hussain, S.; Imran, M.A. The role of artificial intelligence driven 5G networks in COVID-19 outbreak: Opportunities, challenges, and future outlook. Front. Commun. Netw. 2020, 1, 575065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. 5G technology for healthcare: Features, serviceable pillars, and applications. Intell. Pharm. 2023, 1, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; de Carvalho Servia, M.A.; Mowbray, M. Distributional reinforcement learning for inventory management in multi-echelon supply chains. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2023, 6, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, V.G.; Ciano, M.P.; Saltalamacchia, M.; Secchi, R. Artificial intelligence in supply chain and operations management: A multiple case study research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 62, 3333–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmer, L.; von Kleist, H.; de Rochebouët, D.; Tziortziotis, N.; Read, J. Reinforcement learning for supply chain optimization. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Reinforcement Learning 14, Lille, France, 1–3 October 2018; Available online: https://ewrl.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ewrl_14_2018_paper_44.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Grewatsch, S.; Kennedy, S.; Bansal, P. Tackling wicked problems in strategic management with systems thinking. Strateg. Organ. 2023, 21, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doby, L. Supply Chain Shipment Pricing Dataset; USAID US Agency for International Development Data Library: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/divyeshardeshana/supply-chain-shipment-pricing-data (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Global Fund. Global Fund Price and Quality Reporting; Global Fund: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Publicly Available Dataset; Available online: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/sourcing-management/price-quality-reporting/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Cornelius, K. Contextualizing Transformation of Healthcare Sector in Asia-Pacific in the Post-COVID-19 Era. 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12870/4218 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Renaud, J.; Couturier, R.; Guyeux, C.; Courjal, B.; Giot, C. A Comparative Study of Predictive Models for Pharmaceutical Sales Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR), Shanghai, China, 18–20 March 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi; Sharma, P. AI-Enabled Techniques for Intelligent Transportation System for Smarter Use of the Transport Network for Healthcare Services. In Blockchain and Deep Learning for Smart Healthcare; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavididevi, V.; Monikapreethi, S.K.; Rajapriya, M.; Juliet, P.S.; Yuvaraj, S.; Muthulekshmi, M. IoT-Enabled Reinforcement Learning for Enhanced Cold Chain Logistics Performance in Refrigerated Transport. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS), Chennai, India, 4–6 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T.; Singh, S.; Hazela, B.; Srivastava, G. Potentials of Internet of Medical Things: Fundamentals and Challenges. In Federated Learning for Internet of Medical Things; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, A.; Agrawal, R. Is artificial intelligence an enabler of supply chain resiliency post COVID-19? An exploratory state-of-the-art review for future research. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.M.; Liew, N.; Pattnaik, S.; Kures, A.O.; Pinsky, E. Exploring the Transition to Low-Carbon Energy: A Comparative Analysis of Population, Economic Growth, and Energy Consumption in Oil-Producing OECD and BRICS Nations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Specifications |

|---|---|

| LSTM/GRU Networks | Hidden units: 50, 100, 200; Dropout rate: 0.2; Learning rate: 0.001; Batch size: 32; Epochs: 100 with early stopping (patience = 10) |

| Gradient Boosting | Number of estimators: 100, 200, 500; Learning rate: 0.01, 0.1, 0.2; Max depth: 3, 5, 7; Subsample: 0.8, 1.0 |

| Random Forest | Number of trees: 100, 200, 500; Max depth: 5, 10, 15; Min samples split: 2, 5, 10; Min samples leaf: 1, 2, 4 |

| ARIMA | Parameters selected using AIC criteria with grid search over , , |

| PCA | Number of components selected to explain 95% of variance |

| K-Means | Number of clusters determined using elbow method and silhouette analysis |

| Model | MAE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 0.1153 | 0.1767 | 0.4677 |

| Decision Tree | 0.0358 | 0.1295 | 0.7138 |

| Random Forest | 0.0421 | 0.1193 | 0.7570 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.0717 | 0.1183 | 0.7610 |

| ARIMA | 0.0576 | 0.0758 | −0.3573 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | AUC Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.8830 | 0.9036 | 0.8830 | 0.8903 | 0.8344 |

| Random Forest | 0.8599 | 0.8799 | 0.8599 | 0.8677 | 0.8652 |

| SVM | 0.6554 | 0.8553 | 0.6554 | 0.7081 | 0.7741 |

| KNN | 0.7408 | 0.8284 | 0.7408 | 0.7724 | 0.7157 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.4974 | 0.7797 | 0.4974 | 0.5698 | 0.6088 |

| Neural Network | 0.8946 | 0.9240 | 0.8946 | 0.9032 | 0.9650 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, K.M.; Pattnaik, S.; Liew, N.; Kundu, T.; Kures, A.O.; Pinsky, E. Smarter Chains, Safer Medicines: From Predictive Failures to Algorithmic Fixes in Global Pharmaceutical Logistics. Forecasting 2025, 7, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040078

Park KM, Pattnaik S, Liew N, Kundu T, Kures AO, Pinsky E. Smarter Chains, Safer Medicines: From Predictive Failures to Algorithmic Fixes in Global Pharmaceutical Logistics. Forecasting. 2025; 7(4):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040078

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Kathleen Marshall, Sarthak Pattnaik, Natasya Liew, Triparna Kundu, Ali Ozcan Kures, and Eugene Pinsky. 2025. "Smarter Chains, Safer Medicines: From Predictive Failures to Algorithmic Fixes in Global Pharmaceutical Logistics" Forecasting 7, no. 4: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040078

APA StylePark, K. M., Pattnaik, S., Liew, N., Kundu, T., Kures, A. O., & Pinsky, E. (2025). Smarter Chains, Safer Medicines: From Predictive Failures to Algorithmic Fixes in Global Pharmaceutical Logistics. Forecasting, 7(4), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040078