1. Introduction

Accurate seasonal forecasts would assist agricultural stakeholders in minimizing losses that might occur from planting crops that require more precipitation than will occur [

1,

2,

3]. Reliable forecasts allow for more dynamic planning and have the potential to increase a field’s production capabilities greatly [

4,

5,

6]. As it stands, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), specifically the Climate Prediction Center (CPC), provides seasonal forecasts for precipitation in the form of probabilistic distributions of 30-day and 90-day totals. However, these forecasts are not useful for agricultural stakeholders, due to the limited predictability in terms of accuracy and inadequate spatial scale they present [

5,

7,

8]. As such, the exploration of different forecasting methods is warranted.

Sub-seasonal to seasonal (S2S) forecasting has been and remains a challenge to this day [

9,

10,

11,

12]. For an in-depth discussion on the S2S topic, [

13], however a short description of the issue will be presented here. Long thought of as the “predictability desert” by forecasters and researchers alike, S2S forecasting is hindered by the short memory of initial atmospheric conditions and the minimum impact sea-surface temperatures have in S2S forecasts [

13,

14]. Thus, the S2S gap between two-week weather forecasts and long-term climate forecasts remains an important area of research. Two different approaches exist to predict the S2S time scale: numerical weather/climate prediction using dynamical models and statistical methods using historical data to predict weather/climate at various time scales [

13]. Statistical methods cover a variety of problems, from simple persistence models to much more complex machine learning algorithms of pattern recognition and analogue pattern-matching methods. However, statistical methods have long had issues forecasting precipitation because its higher spatial and temporal variability, compared to temperature for example, is a hindrance to statistical techniques [

15,

16]. Thus, dynamical models have been a focus of the S2S problem in recent years, primarily due to the increase in predictive skill on the S2S time scale by atmospheric models in the last two decades [

17]. Operational S2S forecasts using dynamical models are becoming more of a normal in recent years, for example the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) producing operational forecasts out to 42 days, and the CPC producing experimental 3-to-4-week forecasts using dynamical model output. However, the primary drawback of dynamical models is the complexity and computational expense of producing these forecasts [

18]. While dynamical models have shown skill in predicting the S2S time scale, statistical models still have their place, given their relative simplicity compared to dynamical models. Thus, there is still a need for research and analysis on improving S2S forecasts from statistical models, especially within the realm of S2S precipitation-forecasting.

k-nearest neighbors (kNN) is a non-parametric method of pattern classification/regression, respectively denoting data with categorical labels (dry, wet, stormy, etc.) and numerical labels (0 mm, etc.). This algorithm utilizes a set of predictands referred to as labels, each of which have a set of numerical representations of certain properties called predictors or features, stored in a feature vector (we shall refer to these as labeled feature vectors or historical feature vectors). We have our operational (target) data whose feature vector is known, but its label is not (in our case because the target has not yet occured). The objective of kNN is to find which k labeled feature vectors are most similar to, or “nearest,” the target’s feature vector. Once those labeled feature vectors are found, their labels are used to predict the label of the target feature vector. For classification, whichever label is most represented by the k nearest neighbors is predicted to apply best to our target feature vector. For regression, an average of the k nearest neighbors’ predictands is taken and used as the average prediction, which is what was performed for this study.

The foundations of

kNN were first laid in 1951 [

19]. Initially, the method was conceived as the compliment to Fix and Hodges’s naive kernel estimate, which is discussed in both the original paper and the commentary released shortly thereafter [

19,

20]. It was not until the next year that the researchers would introduce the terminology which gives the method its modern name [

21]. In summary, given two distributions (akin to “labels”)

F and

G with an equal number of

p-dimensional samples (

where

M is the number of predictors), a

p-dimensional sample with an unknown distribution (our target feature vector), and an odd positive integer

k (to prevent a tie), the distances of all samples with known distributions from that of the one whose distribution is unknown are found. Whichever of the two distributions owns a majority of the nearest

k samples, it is predicted that the target belongs to that distribution. In addition to this, they gave two important findings; the sample size has a negative correlation with the probability of error, while the number of features in a feature vector has—at least, at its simplest form possible—a positive correlation with the probability of error. In 1967, Cover and Hart proved the upper bound on the method’s probability of error was twice that for Bayes’s method when

[

22]. While using only the single nearest neighbor k = 1 may make the most intuitive sense, it runs the risk of allowing noise or outliers to have an undue effect, especially when several distributions are available, or the data in question are particularly volatile. In 1970, Hellman published his proposed solution and brought us one step closer to the method we know today; the

nearest neighbor method [

23]. Given two positive integers

such that

, the target is predicted to have a label if at least

of the

k nearest neighbors share it. This allowed for sample sets to be composed of samples from more than just two distributions, while retaining the requirement that a significant number of the neighbors should be the same.

As valuable as all this information is, its usefulness is mitigated by one simple fact; an estimation of future precipitation is desired, rather than a classification that denotes a range of quantities. For this method to be of any use, it needs to be adaptable to not just a continuous space but a time series. Fortunately, in 1968, Cover was able to extend his upper error bound from classification to regression. He showed that the large sample risk of the nearest neighbor method was at least less than or equal to half the risk presented by probability distributions such as normal, uniform, and Gaussian [

24].

As such, several attempts at producing an algorithm to predict precipitation with this method have been made by several individuals (e.g., [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]), by comparing feature vectors of daily precipitation and other variables to predict the precipitation of the next day, adding that prediction to the data set and using it to predict the day after, and so on until we have a prediction of the desired length. Attempts at reproducing this have found that while it can be technically accurate on a day-to-day basis, the actual quantity of forecasts can be unduly impacted by extreme bouts of precipitation in the past. Indeed, looking to prior attempts, while

kNN’s ability to predict temperature is impressive, its predictions of precipitation, while promising, can leave something to be desired [

26]. While they can certainly present impressive results, said results tend to be for only a single year, which leaves it open as to whether the method is of quality or simply a favorable year for the method. Given how volatile precipitation can be, improvements are needed for

kNN to be useful for precipitation prediction.

This paper proposes a novel solution. Rather than looking at the daily data for feature vectors, for some target day t, this novel kNN method takes so many days and evenly groups them, using the resulting average as one feature each, which is referred to as the pair. In this context, a is the number of groups, while b is the number of days in each group. Given this method of building a feature vector, the novel KNN results will be used to forecast the total precipitation that occurs 30 days after t. This length of time, one month, is used in place of typical daily or weekly forecasts to assist farmers in determining whether they can expect rain or drought over a long period. This is valuable information when it comes to deciding what to plant, as well as when to perform irrigation.

3. Testing

This method was tested on five stations from Oklahoma, USA, each with at least 90 years of precipitation, minimum temperature, and maximum temperature data where missing values were filled using data from adjacent stations. The annual average of each station, as well as the database period, is given in

Table 1, along with a map of the stations given in

Figure 4. Lahoma, Weatherford, and Chandler are all located in central Oklahoma, with southerly flow driving increases in humidity and related precipitation during the warm season and producing less harsh winter temperatures. Hooker, the northwest-most station located in the Oklahoma panhandle, is an arid region, where precipitation comes in bursts due to isolated thunderstorm activity and infrequent convective systems. Idabel is meanwhile the southeast-most station and likewise the most humid and whose larger precipitation totals come primarily from organized convective systems and synoptic wave activity. For target dates, the 9th, 12th, 15th, 18th, and 21st of each month of the five most recent years made available for this study (2004–2008 for all but Lahoma, which is 2002–2006) were used to ensure diverse results for validation. This gave 25 test target dates per month per station, 300 per station, or 1500 in total. The

k nearest neighbors were identified for each target date to forecast the average precipitation over the next 30 days.

As mentioned in the introduction, a large volume of tests were completed to provide robust quantification of the skill of this method compared to climatology and other

kNN methods. Before this, however, a GFV must be selected. For each month, those same 5 days (9th, 12th, 15th, 18th, and 21st) were used in the 45 years prior to the testing years for validation, resulting in 225 validation target dates per month used to select a GFV via GEM using 1 to 180 spans each 1 to 20 days long, such that the product of the two is between 30 days (one month) and 365 days (one year). The reader is once again directed towards the

Supplementary Materials for a more notational explanation. All possible combinations were exhaustively calculated to find which GFV was most likely to perform well for that particular month. In order to maintain computational efficiency, the calculations were parallelized on the length of the spans (

) so days would only need to be averaged together once, as in

Figure 1. Furthermore, to avoid overfitting, bootstrapping of the 45 years prior was used as appropriate for each of the validation years.

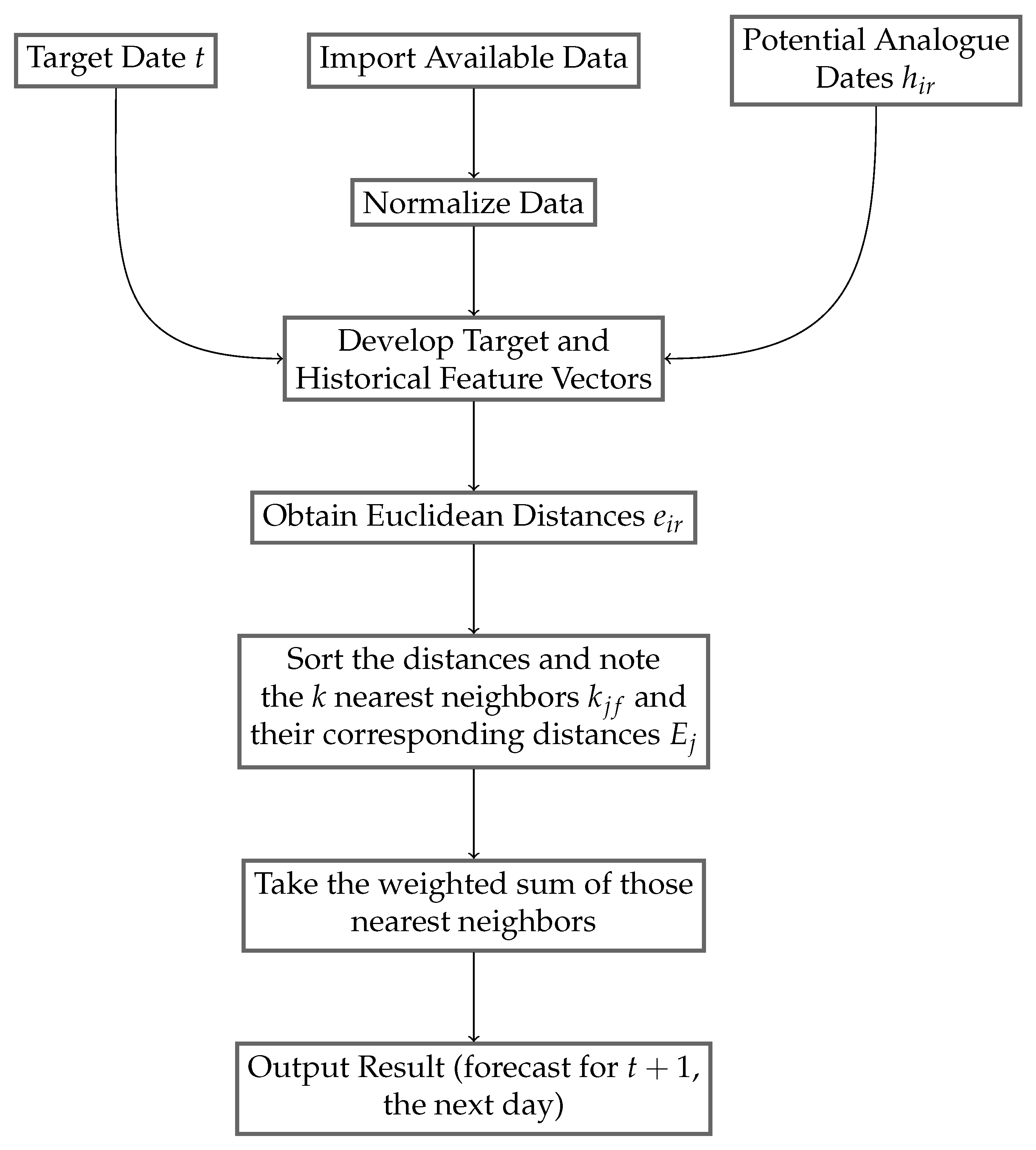

For comparison, four additional methods of forecasting were implemented: a typical

kNN method [

26] as demonstrated graphically in

Figure 3, the state of the art method [

26] (SotA), a support vector machine (SVM) method [

30], and the climatological method. Three of these methods (typical, SotA, and GEM) are similar systems using the same basic concepts of

kNN; however the typical and SotA kNN systems specifically use daily data by fixing their GFV to (365, 1) rather than search through a large set of potential GFVs to identify a good fit as is performed in GEM. Furthermore, the typical method is different from SotA in terms of what it forecasts. SotA forecasts the total precipitation 30 days after

t all at once. Meanwhile, the typical is recursive, only forecasting the precipitation of day

(one day at a time), before adding the predicted forecast to the end of the observed data and repeating the process until

f days are forecast. Once this is calculated, alongside the forecasts for

of all other variables, said forecasts are normalized and the target feature vector is updated to include them. Then, all historical feature vectors are shifted to include the new “future” day and its data, and these new feature vectors are used to forecast day

. This process is repeated up to day

, after which the precipitation forecasted for each day is added together to attain the total forecast. As for climatology, it is simply the average precipitation that occurred from the target date to

f days later averaged over the 30 years before the target date. This method is used as a baseline to evaluate the usefulness and skills of each forecast. Finally, to compare all of the above with a more widely-used methodology, a support vector machine regression (SVM) methodology was implemented. The reader is directed to [

31] for more information on the SVM’s algorithm. Here, however, we shall mention that in order to build the feature vectors necessary to train the SVM, the same method used for SotA was used. A Gaussian kernel function was used for training and hyperparameter optimization, and data was standardized in the same manner described for all the kNN experiments. The optimization routine used was the Sequential Minimization Optimization as selected by default, as well as all other defaults used by MATLAB’s (R2023b) fitrsvm function which was used for building this method of the study.

The

root mean squared error (RMSE) is used to assess the quality of forecasts. Let

e be the set of forecasts (either those found with GEM, SotA, typical, or climatology) and

o the corresponding set of observed data.

where

m is the number of target days tested.

While useful, the RMSE can be oversensitive to outliers and extreme errors. As such, the

absolute mean relative error (MRE) is also used, where

A comparison to the overall observed precipitation average was implemented, with said average being

. Then, the

Nash-Sutcliffe coefficient (NS), given by

is a comparison with the observed average, with a range

. If

is negative, the forecasting method tested performed poorly, the observed average being generally superior. If

, the method performed at least as well as the observed average, with greater

correlating to greater performance. An

means the method forecasted all target dates perfectly, meaning it had an RMSE of 0.

Significance testing was performed via the Mann-Whitney

U-test [

32] to ensure that the differences between GEM and SotA results were significant. All tests were performed for each individual station with a significance level of

= 0.05, meaning that if the

p-value given by the

U-test was below 0.05, GEM’s distribution is assumed to be significantly different to that of SotA. Seeing as how being both superior and distinct to SotA was the priority,

U tests were only performed on GEM and SotA together.

And finally, reliability graphs [

33] were composed to look at how consistently the predictions performed. To create these graphs, all forecast data, and their corresponding observed values, are binned into discrete 10 mm wide bins. Then, the average values of both the binned forecasts and their corresponding observations are taken. An example of this process is given in the form of

Table 2. The final reliability graph depicts the average forecast versus average observed values for those forecasts to show how “reliable” the forecast system is in reproducing specific binned values of data. Observed averages below the forecast average represent an overestimation for that specific forecast bin and when the observed average is higher than the forecast average that means the forecast system is underestimating the observed values for that range of forecast values.

4. Results and Discussion

The RMSEs, MREs, and NSs of each station are given in

Figure 5. Idabel had the highest RMSE across all five stations, whereas Hooker had the lowest. In all five cases GEM produced a lower RMSE than those produced by climatology and the other

kNN methods.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 contain scatter plots of forecasts produced by GEM, SotA, and climatology, all being compared to the average precipitation observed

f days after the target day. Due to the similarities of SotA and the typical

kNN results, plots of the latter were omitted from

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

Applying the GEM method resulted in non-ideal but nonetheless higher quality forecasts. For the target dates tested, GEM produced a greater Nash-Sutcliffe coefficient than either the SotA, typical , or the climatological forecasts. Save for Hooker and Idabel, all GEM NS are greater than 0.17. For typical kNN, Hooker and Idabel have negative NS, with Weatherford at 0.026 and Chandler the only one to exceed 0.15. SotA has somewhat better results, in that Lahoma’s NS is positive, and Chandler and Weatherford also saw minor improvements to their NS. However, Hooker and Idabel performed markedly worse when using SotA compared to the typical kNN. And for climatology, Hooker and Idabel are below 0.1, with the rest being below 0.2.

All stations achieved superior RMSE, MRE, and NS when using GEM compared to SotA, typical, or climatology. This indicates that GEM not only produced superior forecasts, but when it did, these forecasts had a non-trivial improvement over climatology.

It should be noted that there is a positive correlation between average total annual precipitation and RMSE, in that for , the station with the greatest total annual precipitation also had the greatest RMSE. This is the case regardless of the forecasting method used.

Looking at

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 gives important insights into these statistical measures. Climatology is extremely prone to underestimation, typically several centimeters short of the observed amounts on higher precipitation days. Using SotA does fix this to an extent, especially regarding the cold season, but it is only when GEM is implemented that more extreme forecasts are made. Unfortunately, this also brings about an opposite problem: overestimation. Both of these problems are to be expected, seeing as the forecasts are built using weighted averages. As such, while all methods have instances of this, GEM’s willingness to make forecasts that exceed the upper bounds of the others’ predictions can result in forecasts that go further past lower observations as they do approach higher ones. And, as can be seen in

Figure 8, the SVM is even less likely to make extreme forecasts, with the forecasts it makes clustered into several more noticeable clumps. With the exception of Lahoma, forecasts using this method also seem to lock up in a straight line similar to what occurs in climatology. This falls in line with the performance seen in [

34], where both

kNN and SVM performed poorly.

One can also look to the aforementioned figures for the differences in performance at different times of the year, with red circles indicating the warm season of March through September, and blue being the cold, October through February. During the warm season, GEM is likely to make lower forecasts, regardless of observed precipitation. Interestingly, though, Idabel is just as likely to over-forecast during the warm season, and in Chandler it rarely under-forecasts at all. For both SotA and climatology, forecasts skew into a mix of over and under-forecasting for both the warm and cold seasons, though much like with GEM, their seasonal forecasts at all stations sans Idabel can be clearly distinguished by the range of values each method was willing to put out.

Figure 9, meanwhile, is a demonstration of how GEM (the highest performing of the three

kNN implementations) performed in monthly forecasts of the testing data. The purpose of this is to give a visual aid for not only how GEM is meeting individual forecasts, but how well it is able to match the trends of the observed data. For GEM, all stations had a correlation coefficient above 0.25, with the highest being Chandler at 0.512, and the lowest being Idabel at 0.263. Alphabetically, GEM has an RMSE of 54.465, 41.937, 75.829, 41.32, and 56.953 mm for these graphs. With climatology, the resulting correlation coefficients were universally lower, with its higest being Weatherford at 0.428 and its lowest being Idabel at 0.101. Alphabetically, climatology has an RMSE of 59.015, 43.280, 78.937, 44.552, and 58.634 mm for these graphs. Alphabetically, SVM has an RMSE of 60.412, 44.995, 80.040, 46.488, and 61.358 mm for these graphs. By its nature as the 30-year average, the climatological forecast takes on a seasonal cycle, making any similarities to the observed trend coincidental. GEM, however, has a much more interesting relationship. Although it rarely predicts the heavier precipitation totals accurately, GEM’s forecasts often will ”peak” in comparison to the forecasts made a month prior and after, suggesting a level of sensitivity to the larger precipitation values. Examples of this trend can be seen in most larger precipitation totals, with exceptions for Lahoma, and the earliest peak that occurs in Weatherford. It should be noted that the GEM forecast shown in the above results is a weighted average from the

k nearest neighbors identified by the GEM system, thus this represents not a single instance of a precipitation prediction but a smoothed average. The spread of the nearest neighbor forecast values extends beyond the observed values in most cases (outside of extreme values).

Of the 5 stations, Hooker, Lahoma, and Weatherford’s GEM forecasts were found to be significantly different from those of SotA, with

p-values of 0.029, 0.019, and 0.002, respectively. Chandler and Idabel, meanwhile, had

p-values of 0.800 and 0.144, respectively, which means they failed to provide statistically significant improvements. Given that, as shown in

Figure 4, these two stations experience the most extreme precipitation, the GEM method may have a ceiling regarding its usefulness in making quality forecasts for higher. It may also be worth noting that Chandler and Idabel are the two east-most of the five stations, potentially suggesting a decrease in GEM’s feasibility as stations move closer to the ocean. In either case, further study is necessary before conclusions should be drawn. When compared with climatology, the differences are more apparent both in Figures and in these statistics, with Chandler, Hooker, Lahoma, and Weatherford having

p-values of less than 0.001 while only Idabel had an extreme

p-value of 0.947.

Figure 10 shows the reliability graphs for each station. For lower precipitation totals, the averaged forecasts and observed precipitations are relatively close. The primary exception to this is Idabel at 30–50 mm. Once the expected forecasts pass a certain threshold, however, they are found to be generally lacking. In the cases of Chandler and Weatherford, they tend to underestimate, while Hooker and Lahoma overestimate. This points to a systemic bias in the methodologies provided, specifically a preference for lower forecasts. Once again, the exception seems to be Idabel; however this should not necessarily be taken as evidence of quality. Looking back to

Figure 7, while many of the extreme forecasts are accurate, moderate forecasts have several examples of over and under-forecasting to give the results seen in

Figure 10. The best way to counter this shortcoming is to lower the

k value needed to create quality forecasts. Since the forecast itself is an average of prior precipitation amounts, by definition, the few extreme precipitation events considered will be diluted by typical. Another option is to perhaps give more weight to extreme precipitation when calculating the total forecast; however, this runs the risk of creating an opposite problem where typical occurrences of precipitation become difficult to forecast.

Table 3.

The correlation coefficients of each of the methods tested to the observed forecasts.

Table 3.

The correlation coefficients of each of the methods tested to the observed forecasts.

| Stations | | | | | |

|---|

| Chandler | 0.512 | 0.419 | 0.224 | 0.517 | 0.218 |

| Hooker | 0.382 | 0.276 | 0.296 | 0.292 | 0.130 |

| Idabel | 0.263 | 0.101 | −0.157 | 0.105 | 0.082 |

| Lahoma | 0.487 | 0.385 | 0.379 | 0.451 | 0.241 |

| Weatherford | 0.482 | 0.428 | −0.303 | 0.511 | 0.360 |

For SotA, some similarities in shape to GEM can be observed in Chandler and Hooker; however, it is otherwise quite different. In the cases of Chandler, Idabel, and Lahoma, SotA was usually unable to produce forecasts greater than those of GEM. While it is able to do so in Weatherford, it is only able to make over-forecasts, whereas in Hooker, where both GEM and SotA tend to over-forecast, SotA’s are slightly more extreme.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, climatology has the fewest extremes of these three forecasting methods. It will have the lowest range of forecasted precipitation, particularly noticeable in Chandler, Lahoma, and Weatherford, and lacking extreme deviation from the 1:1 line, or at least rarely to the extreme of its kNN counterparts. The main exceptions to this are in Hooker where its lowest forecasts correlate to observed precipitation nearly seven times greater, as well as Weatherford where forecasts around 140 mm correlate to observed precipitation nearly double that on average.

Take note of the performance during the warm and cold seasons for most stations. In

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, while there can be some overlap, forecasts from each season are clearly segregated. This is not the case for the more humid region of Idabel, where the warm and cold seasons’ forecasts are mixed. Most likely, the change in performance is a consequence of the greater range of possible precipitation over the span of 30 days. Since humid regions such as Idabel have such variance in their precipitation, averages of past precipitation tend to not allow for forecasts close to 0 mm, unlike stations in arid climates. In short, the differences in precipitation variances between wet and dry months and between wet and cold months might have played some role in affecting the forecast performance between Idabel and Hooker stations.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a novel method of performing kNN was introduced and tested for five different stations across Oklahoma, being compared to the climatological average as well as the typical and state of the art methodologies for kNN. This comparison was performed by noting the RMSE, MRE, and NS of all methodologies’ forecasts of the total precipitation 30 days after several target dates. Additionally, statistical significance of the results were measured, and reliability graph were made to determine whether the novel GEM method was not only superior, but distinct to those others.

The GEM method was demonstrated as superior to all other methods in this study. While far from perfect, GEM universally had a lower RMSE and MRE than all other methods, and was the only method to maintain a positive NS across all five stations. The conclusions drawn by GEM were found to be statistically significantly different from those of SotA, which implies that with refinement the program could continue to improve on those results. However, the improvement, while distinct as told by the statistical significance tested, is minor, suggesting that the skill of kNN as a whole may be limited in this context.

A greater quantity of historical data, as well as parameters with a correlation to precipitation such as el nino/la nina patterns and moisture flux, would greatly improve the quality of the method, which will be investigated in the future. Further, studies of data outside of Oklahoma would be useful in expanding our understanding of the limitations of this method. As it stands, this research only examines the method’s performance for regions in Oklahoma. While the climates of Oklahoma can in and of themselves be volatile, testing in different regions is necessary to assess this method’s effectiveness beyond Oklahoma. A look into gridded rainfall data may also be necessary, as the station-centric methodology employed here can be blind to other forms of data useful to forecasting precipitation. Additionally, efforts will be made to create a range in which forecasts are made to try and include the observed forecast in as small a range as feasible, using as few years of historical data as possible to try and discern the minimum necessary data to create accurate predictions.