Non-Negative Forecast Reconciliation: Optimal Methods and Operational Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Forecast Reconciliation

2.1. Zero-Constrained and Structural Representation

2.2. Regression-Based Reconciliation

2.3. Iterative Cross-Temporal Reconciliation

- Step 1

- compute the temporally reconciled forecasts () for each variable of ;

- Step 2

- compute the time-by-time cross-sectional reconciled forecasts () for all the temporal aggregation levels of .

3. Non-Negative Reconciliation

- The Negative Forecasts Correction Algorithm (nfca), an iterative correction procedure proposed by Kourentzes and Athanasopoulos [37].

- The bottom-up and top-down variants of the Set-Negative-To-Zero (sntz) procedure [20], which are very simple, competitive in accuracy, and computationally faster compared to the more intensive nonlinear optimization methods.

3.1. Block Principal Pivoting (bpv)

3.2. Operator Splitting Quadratic Program (osqp)

3.3. Negative Forecasts Correction Algorithm (nfca)

3.4. Iterative Non-Negative Reconciliation with Immutable Constraints (NNIC)

3.5. Set-Negative-to-Zero (sntz): Bottom-Up and Top-Down Variants

- A numerical illustration

- General formulation of

- Proportional distribution, :

- Squared proportional distribution, :

- Variance-weighted distribution, :

4. Australian Tourism Demand Dataset

4.1. Forecasting Experiment

- Optimal cross-sectional approach with shrinkage covariance matrix [12];

- Optimal temporal approach with diagonal covariance matrix based on the temporal structural matrix [16];

- Optimal temporal approach with diagonal covariance matrix based on in-sample residuals [16];

- Optimal cross-temporal approach with diagonal covariance matrix based on the temporal structural matrix [16];

- Optimal cross-temporal approach with diagonal covariance matrix based on in-sample residuals [19];

- Optimal cross-temporal approach with block-diagonal covariance matrix based on in-sample residuals [19].

4.2. Performance Measures for Multiple Comparisons

4.3. Non-Negative Reconciled Forecasts

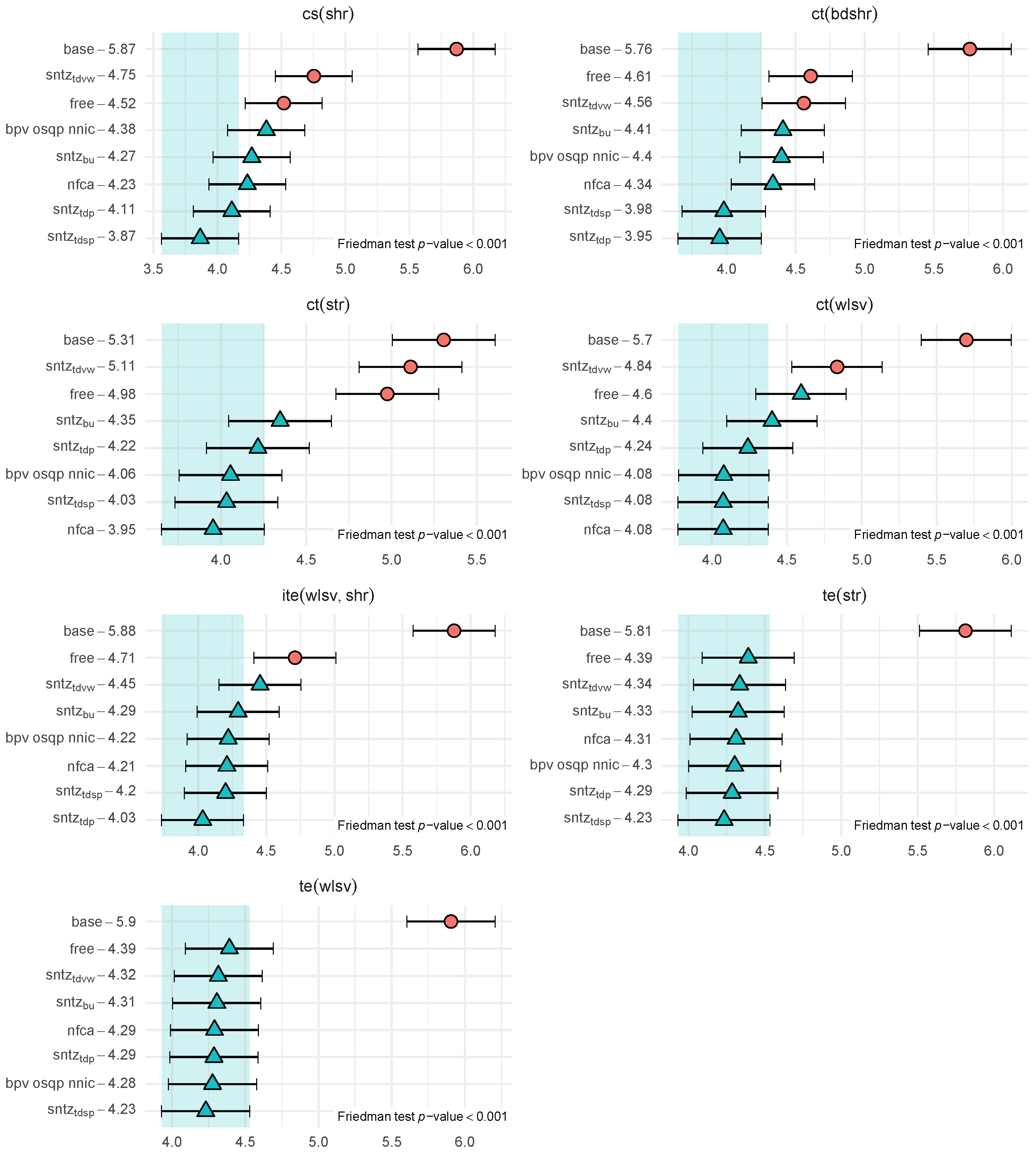

4.4. Results

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. NNIC vs. NNLS Algorithms

Appendix B. Australian Tourism Demand: Tables and Figures

- geographic division of the Australian Tourism Demand dataset (Table A1);

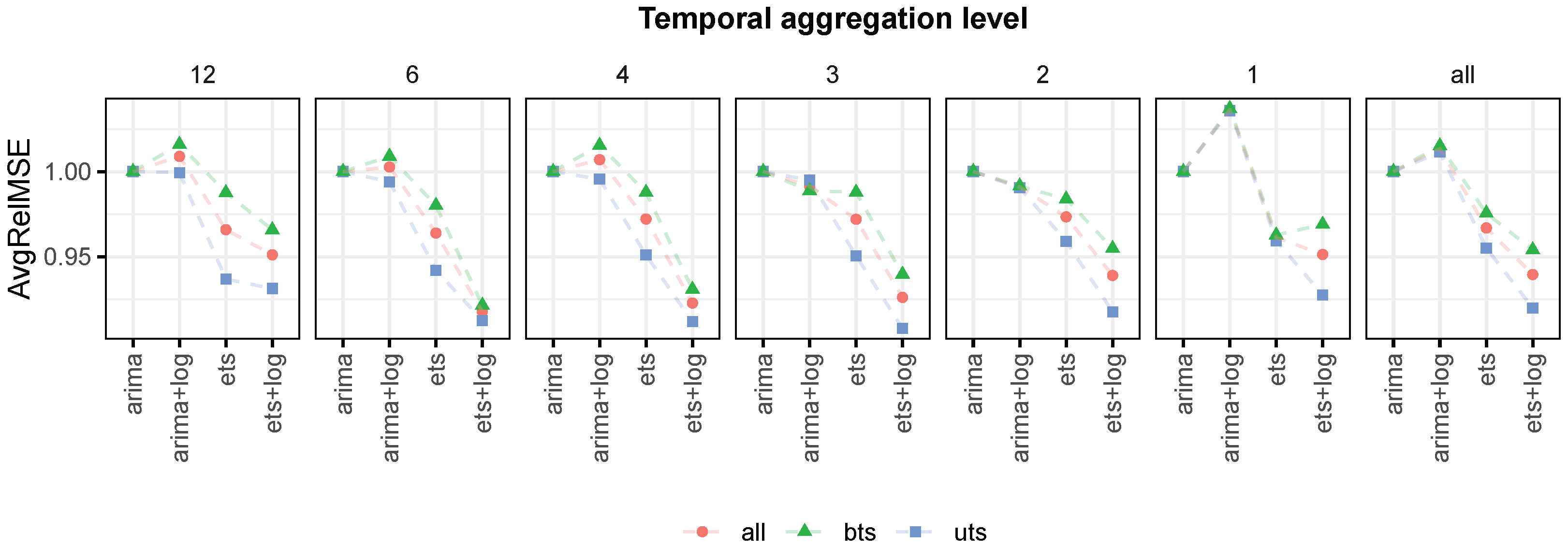

- average relative MSE (AvgRelMSE) for the automatic ARIMA and ETS base forecasts on both levels and log-transformed data;

| Serie | Name | Label | Serie | Name | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Continue: Regions | ||||

| 1 | Australia | Total | 49 | Gippsland | BCB |

| States | 50 | Phillip Island | BCC | ||

| 2 | New South Wales (NSW) | A | 51 | Central Murray | BDA |

| 3 | Victoria (VIC) | B | 52 | Goulburn | BDB |

| 4 | Queensland (QLD) | C | 53 | High Country | BDC |

| 5 | South Australia (SA) | D | 54 | Melbourne East | BDD |

| 6 | Western Australia (WA) | E | 55 | Upper Yarra | BDE |

| 7 | Tasmania (TAS) | F | 56 | MurrayEast | BDF |

| 8 | Northern Territory (NT) | G | 57 | Mallee | BEA |

| Zones | 58 | Wimmera | BEB | ||

| 9 | Metro NSW | AA | 59 | Western Grampians | BEC |

| 10 | Nth Coast NSW | AB | 60 | Bendigo Loddon | BED |

| Sth Coast NSW | AC | 61 | Macedon | BEE | |

| 11 | Sth NSW | AD | 62 | Spa Country | BEF |

| 12 | Nth NSW | AE | 63 | Ballarat | BEG |

| ACT | AF | 64 | Central Highlands | BEG | |

| 13 | Metro VIC | BA | 65 | Gold Coast | CAA |

| West Coast VIC | BB | 66 | Brisbane | CAB | |

| 14 | East Coast VIC | BC | 67 | Sunshine Coast | CAC |

| 15 | Nth East VIC | BD | 68 | Central Queensland | CBA |

| 16 | Nth West VIC | BE | 69 | Bundaberg | CBB |

| 17 | Metro QLD | CA | 70 | Fraser Coast | CBC |

| 18 | Central Coast QLD | CB | 71 | Mackay | CBD |

| 19 | Nth Coast QLD | CC | 72 | Whitsundays | CCA |

| 20 | Inland QLD | CD | 73 | Northern | CCB |

| 21 | Metro SA | DA | 74 | Tropical North Queensland | CCC |

| 22 | Sth Coast SA | DB | 75 | Darling Downs | CDA |

| 23 | Inland SA | DC | 76 | Outback | CDB |

| 24 | West Coast SA | DD | 77 | Adelaide | DAA |

| 25 | West Coast WA | EA | 78 | Barossa | DAB |

| Nth WA | EB | 79 | Adelaide Hills | DAC | |

| Sth WA | EC | 80 | Limestone Coast | DBA | |

| Sth TAS | FA | 81 | Fleurieu Peninsula | DBB | |

| 26 | Nth East TAS | FB | 82 | Kangaroo Island | DBC |

| 27 | Nth West TAS | FC | 83 | Murraylands | DCA |

| 28 | Nth Coast NT | GA | 84 | Riverland | DCB |

| 29 | Central NT | GB | 85 | Clare Valley | DCC |

| Regions | 86 | Flinders Range and Outback | DCD | ||

| 30 | Sydney | AAA | 87 | Eyre Peninsula | DDA |

| 31 | Central Coast | AAB | 88 | Yorke Peninsula | DDB |

| 32 | Hunter | ABA | 89 | Australia’s Coral Coast | EAA |

| 33 | North Coast NSW | ABB | 90 | Experience Perth | EAB |

| 34 | South Coast | ACA | 91 | Australia’s SouthWest | EAC |

| 35 | Snowy Mountains | ADA | 92 | Australia’s North West | EBA |

| 36 | Capital Country | ADB | 93 | Australia’s Golden Outback | ECA |

| 37 | The Murray | ADC | 94 | Hobart and the South | FAA |

| 38 | Riverina | ADD | 95 | East Coast | FBA |

| 39 | Central NSW | AEA | 96 | Launceston, Tamar and the North | FBB |

| 40 | New England North West | AEB | 97 | North West | FCA |

| 41 | Outback NSW | AEC | 98 | WildernessWest | FCB |

| 42 | Blue Mountains | AED | 99 | Darwin | GAA |

| 43 | Canberra | AFA | 100 | Kakadu Arnhem | GAB |

| 44 | Melbourne | BAA | 101 | Katherine Daly | GAC |

| 45 | Peninsula | BAB | 102 | Barkly | GBA |

| 46 | Geelong | BAC | 103 | Lasseter | GBB |

| 47 | Western | BBA | 104 | Alice Springs | GBC |

| 48 | Lakes | BCA | 105 | MacDonnell | GBD |

Appendix C. Solver Hyperparameters and Computational Environment

- max_iter = 10000, check_termination = 25, eps_abs = 1e–5, eps_rel = 0,eps_dual_inf = 1e–7, polish = TRUE, polish_refine_iter = 500(Cross-sectional reconciliation); max_iter = 10000, check_termination = 20,eps_abs = 1e–5, eps_rel = 1e–6, eps_dual_inf = 1e–7, polish = TRUE,polish_refine_iter = 100 (Temporal reconciliation); max_iter = 1000000,check_termination = 20, eps_abs = 1e–6, eps_rel = 0, polish = TRUE,polish_refine_iter = 500 (Cross-temporal reconciliation);

- tol = 1e–5, itmax = 100.

- tol = 1e–3, itmax = 100.

- ptype = "fixed", par = 10, tol = gtol = sqrt(.Machine$double.eps),itmax = 100.

References

- Petropoulos, F.; Apiletti, D.; Assimakopoulos, V.; Babai, M.; Barrow, D.; Bergmeir, C.; Bessa, R.; Boylan, J.; Browell, J.; Carnevale, C.; et al. Forecasting: Theory and practice. Int. J. Forecast. 2022, 38, 705–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourentzes, N. Toward a one-number forecast: Cross-temporal hierarchies. Foresight Int. J. Appl. Forecast. 2022, 67, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Ahmed, R.A.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Shang, H.L. Optimal combination forecasts for hierarchical time series. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2011, 55, 2579–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Hyndman, R.J.; Kourentzes, N.; Panagiotelis, A. Forecast reconciliation: A review. Int. J. Forecast. 2024, 40, 430–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangerfield, B.; Morris, J. Top-down or bottom-up: Aggregate versus disaggregate extrapolations. Int. J. Forecast. 1992, 6, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcutt, G.H.; Watts, H.W.; Edwards, J.B. Data aggregation and information loss. Am. Econ. Rev. 1968, 58, 773–787. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1815532 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Dunn, D.M.; Williams, W.H.; Dechaine, T.L. Aggregate versus subaggregate models in local area forecasting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1976, 71, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.W.; Sohl, J.E. Disaggregation methods to expedite product line forecasting. J. Forecast. 1990, 9, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliedner, G. Hierarchical forecasting: Issues and use guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2001, 101, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Ahmed, R.A.; Hyndman, R.J. Hierarchical forecasts for Australian domestic tourism. Int. J. Forecast. 2009, 25, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Lee, A.J.; Wang, E. Fast computation of reconciled forecasts for hierarchical and grouped time series. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2016, 97, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasuriya, S.L.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Hyndman, R.J. Optimal Forecast Reconciliation for Hierarchical and Grouped Time Series Through Trace Minimization. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2019, 114, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasuriya, S.L.; Turlach, B.A.; Hyndman, R.J. Optimal non-negative forecast reconciliation. Stat. Comput. 2020, 30, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotelis, A.; Gamakumara, P.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Hyndman, R.J. Probabilistic forecast reconciliation: Properties, evaluation and score optimisation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotelis, A.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Gamakumara, P.; Hyndman, R.J. Forecast reconciliation: A geometric view with new insights on bias correction. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Hyndman, R.J.; Kourentzes, N.; Petropoulos, F. Forecasting with temporal hierarchies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 262, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrup, P.; Lindström, E.; Pinson, P.; Madsen, H. Temporal hierarchies with autocorrelation for load forecasting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourentzes, N.; Athanasopoulos, G. Cross-temporal coherent forecasts for Australian tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fonzo, T.; Girolimetto, D. Cross-temporal forecast reconciliation: Optimal combination method and heuristic alternatives. Int. J. Forecast. 2023, 39, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fonzo, T.; Girolimetto, D. Spatio-temporal reconciliation of solar forecasts. Sol. Energy 2023, 251, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolimetto, D.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Di Fonzo, T.; Hyndman, R.J. Cross-temporal probabilistic forecast reconciliation: Methodological and practical issues. Int. J. Forecast. 2024, 40, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, J.; Ternes, M.; Wilms, I. Cross-temporal forecast reconciliation at digital platforms with machine learning. Int. J. Forecast. 2025, 41, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, C.L.P.; van Dalen, J. Integrated hierarchical forecasting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 263, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmy, J.P.; Maldonado, S. Hierarchical time series forecasting via support vector regression in the European travel retail industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 137, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, S.; Singh, S.P.; Madaan, J.K. A cross-temporal hierarchical framework and deep learning for supply chain forecasting. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Quan, H.; Disfani, V.R.; Liu, L. Reconciling solar forecasts: Geographical hierarchy. Sol. Energy 2017, 146, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Quan, H.; Disfani, V.R.; Rodríguez-Gallegos, C.D. Reconciling solar forecasts: Temporal hierarchy. Sol. Energy 2017, 158, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. A guideline to solar forecasting research practice: Reproducible, operational, probabilistic or physically-based, ensemble, and skill (ROPES). J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 022701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Taieb, S.; Taylor, J.W.; Hyndman, R.J. Hierarchical probabilistic forecasting of electricity demand with smart meter data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2021, 116, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.E.; Peter, N.; Møller, J.K.; Henrik, M. Reconciliation of wind power forecasts in spatial hierarchies. Wind Energy 2023, 26, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolghasemi, M.; Girolimetto, D.; Di Fonzo, T. Improving cross-temporal forecasts reconciliation accuracy and utility in energy market. Appl. Energy 2025, 394, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollyman, R.; Petropoulos, F.; Tipping, M.E. Understanding forecast reconciliation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fonzo, T.; Girolimetto, D. Forecast combination-based forecast reconciliation: Insights and extensions. Int. J. Forecast. 2024, 40, 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Gamakumara, P.; Panagiotelis, A.; Hyndman, R.J.; Affan, M. Hierarchical Forecasting. In Macroeconomic Forecasting in the Era of Big Data; Fuleky, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 52, pp. 689–719. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, C.L.; Hanson, R.J. Solving Least Squares Problems; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Júdice, J.J.; Pires, F.M. A Block Principal Pivoting Algorithm for Large-Scale Strictly Monotone Linear Complementarity Problems. Comput. Oper. Res. 1994, 21, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourentzes, N.; Athanasopoulos, G. Elucidate structure in intermittent demand series. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 288, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, B.; Banjac, G.; Goulart, P.; Bemporad, A.; Boyd, S. OSQP: An operator splitting solver for quadratic programs. Math. Program. Comput. 2020, 12, 637–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, Y.; Panagiotelis, A.; Li, F. Optimal reconciliation with immutable forecasts. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 308, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolimetto, D.; Di Fonzo, T. FoReco: Forecast Reconciliation, Version 1.1.0; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Girolimetto, D.; Di Fonzo, T. Point and probabilistic forecast reconciliation for general linearly constrained multiple time series. Stat. Methods Appl. 2024, 33, 581–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, J.R.; Neudecker, H. Matrix Differential Calculus with Applications in Statistics and Econometrics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, R.; Champernowne, D.G.; Meade, J.E. The precision of national income estimates. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1942, 9, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, R.P. The Estimation of Large Social Account Matrices. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1978, 141, 359–367, Erratum in J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1979, 142, 405. https://doi.org/10.2307/2982515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrup, P.; Lindström, E.; Møller, J.K.; Madsen, H. Dimensionality reduction in forecasting with temporal hierarchies. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1127–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagli, G.M.; Yang, D.; Srinivasan, D. Reconciling solar forecasts: Sequential reconciliation. Sol. Energy 2019, 179, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, E.J.; Karjalainen, U.P. Component reconstruction in the primary space of spectra and concentrations. Alternating regression and related direct methods. Anal. Chim. Acta 1991, 250, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.W.; Browne, M.; Langville, A.N.; Pauca, V.P.; Plemmons, R.J. Algorithms and applications for approximate nonnegative matrix factorization. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 52, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Plemmons, R.J. Nonnegativity constraints in numerical analysis. In The Birth of Numerical Analysis; World Scientific: Singapore, 2009; pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, B.; Banjac, G.; Goulart, P.; Boyd, S.; Anderson, E. Package OSQP: Quadratic Programming Solver Using the ‘OSQP’ Library, Version 0.6.3.3; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Parikh, N.; Chu, E.; Peleato, B.; Eckstein, J. Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 2011, 3, 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, D.; Mercier, B. A dual algorithm for the solution of nonlinear variational problems via finite element approximation. Comput. Math. Appl. 1976, 2, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Benthem, M.H.; Keenan, M.R. Fast algorithm for the solution of large-scale non-negativity-constrained least squares problems. J. Chemom. 2004, 18, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Koehler, A.B.; Ord, J.K.; Snyder, R.D. Forecasting with Exponential Smoothing. The State Space Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Bergmeir, C.; Caceres, G.; Chhay, L.; O’Hara-Wild, M.; Petropoulos, F.; Razbash, S.; Wang, E.; Yasmeen, F. Forecast: Forecasting Functions for Time Series and Linear Models, Version 8.24.0; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Khandakar, Y. Automatic time series forecasting: The forecast package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, A.J.; Franses, P.H.; Hibon, M.; Stekler, H.O. The M3 competition: Statistical tests of the results. Int. J. Forecast. 2005, 21, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S.; Spiliotis, E.; Assimakopoulos, V. The M5 Accuracy competition: Results, findings and conclusions. Int. J. Forecast. 2022, 38, 1346–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourentzes, N.; Svetunkov, I.; Schaer, O. Tsutils: Time Series Exploration, Modelling and Forecasting, Version 0.9.4; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Kourentzes, N. On the evaluation of hierarchical forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 2022, 39, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Framework | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Description | cs | te | ct |

| vector of true (unknown) coherent vector | ||||

| vector of incoherent base forecasts | ||||

| vector of reconciled forecasts | ||||

| zero-constraints matrix such that | ||||

| structural matrix | ||||

| Total number of elements in the vectors | n | |||

| , | Numbers of row and colum in the zero-constraints matrix and the structural matrix , respectively | , | , m | , |

| vector of target forecasts corrisponding to the free components (cross-sectional)/high-frequency univariate series (temporal)/high-frequency free series (cross-temporal) | ||||

| Type of Forecast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | |||||

| 40 | 45 | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| 35 | 35 | 31.1 | 30.4 | 31 | |

| −5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 10 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 9 | |

| Number of Series | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical Division (GD) | Purpose of Travel (PoT) | Total | |

| Australia | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| States | 7 | 28 | 35 |

| Zones * | 21 | 84 | 105 |

| Regions | 76 | 304 | 380 |

| Total | 105 | 420 | 525 |

| k | Tot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Series | 1 | 7 | 21 | 76 | 4 | 28 | 84 | 304 | 525 |

| 1 | 13 | 1 | 25 | 200 | 239 | ||||

| (17%) | (4%) | (30%) | (66%) | (46%) | |||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 131 | 146 | ||||

| (1%) | (4%) | (15%) | (43%) | (28%) | |||||

| 3 | 6 | 98 | 104 | ||||||

| (7%) | (32%) | (20%) | |||||||

| 4 | 3 | 76 | 79 | ||||||

| (4%) | (25%) | (15%) | |||||||

| 6 | 54 | 54 | |||||||

| (18%) | (10%) | ||||||||

| 12 | 16 | 16 | |||||||

| (5%) | (3%) |

| Label | # rep | # series | Values | # rep | # series | Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | max | min | max | min | max | min | max | |||

| Monthly forecasts () | Two-monthly forecasts () | |||||||||

| 85 | 2 | 12 | −58.35 | −0.00031 | 85 | 1 | 8 | −83.01 | −0.00064 | |

| 41 | 1 | 4 | −4.81 | −0.01459 | 7 | 1 | 1 | −1.27 | −0.06806 | |

| 43 | 1 | 5 | −5.29 | −0.00514 | 5 | 1 | 1 | −1.13 | −0.18561 | |

| 85 | 2 | 8 | −18.89 | −0.00125 | 73 | 1 | 4 | −21.21 | −0.00102 | |

| 85 | 10 | 32 | −45.33 | −0.00004 | 85 | 1 | 17 | −71.76 | −0.00510 | |

| 85 | 1 | 6 | −29.97 | −0.00558 | 60 | 1 | 4 | −30.81 | −0.01798 | |

| 85 | 2 | 13 | −21.12 | −0.00064 | 84 | 1 | 8 | −20.15 | −0.00558 | |

| Quarterly forecasts () | Four-monthly forecasts () | |||||||||

| 79 | 1 | 6 | −71.64 | −0.00051 | 69 | 1 | 4 | −53.33 | −0.00108 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 – | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 – | |

| 49 | 1 | 3 | −20.60 | −0.00064 | 42 | 1 | 3 | −23.73 | −0.00851 | |

| 84 | 1 | 10 | −84.84 | −0.00765 | 79 | 1 | 8 | −100.25 | −0.00223 | |

| 31 | 1 | 2 | −19.00 | −0.01225 | 25 | 1 | 3 | −21.76 | −0.06677 | |

| 82 | 1 | 6 | −26.81 | −0.00231 | 71 | 1 | 5 | −30.29 | −0.00017 | |

| Semi-annual forecasts () | Annual forecasts () | |||||||||

| 42 | 1 | 2 | −26.78 | −0.00734 | 5 | 1 | 1 | −23.60 | −0.60212 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 21 | 1 | 3 | −23.07 | −0.01458 | 5 | 1 | 1 | −16.51 | −1.89363 | |

| 69 | 1 | 7 | −130.78 | −0.05021 | 43 | 1 | 2 | −131.82 | −0.19975 | |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | −19.76 | −0.39761 | 4 | 1 | 1 | −12.83 | −1.74552 | |

| 56 | 1 | 3 | −35.96 | −0.01885 | 9 | 1 | 1 | −33.97 | −1.08399 | |

| Temporal Aggregation Level | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 12 | all | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 12 | all |

| 0.979279 | 0.977149 | 0.968516 | 0.959679 | 0.950190 | 0.942428 | 0.971733 | 0.978197 | 0.981807 | 0.979275 | 0.970618 | 0.955839 | 0.948815 | 0.975631 | |

| 0.977990 | 0.976276 | 0.968187 | 0.959392 | 0.950029 | 0.942396 | 0.970907 | 0.978193 | 0.981805 | 0.979276 | 0.970617 | 0.955841 | 0.948814 | 0.975628 | |

| 0.977953 | 0.976012 | 0.968163 | 0.959401 | 0.950000 | 0.942398 | 0.970831 | 0.978193 | 0.981805 | 0.979276 | 0.970617 | 0.955841 | 0.948814 | 0.975628 | |

| 0.978009 | 0.976293 | 0.968147 | 0.959379 | 0.949981 | 0.942395 | 0.970908 | 0.978194 | 0.981804 | 0.979276 | 0.970616 | 0.955843 | 0.948813 | 0.975629 | |

| 0.978054 | 0.976361 | 0.968155 | 0.959399 | 0.949989 | 0.942387 | 0.970946 | 0.978192 | 0.981803 | 0.979274 | 0.970615 | 0.955841 | 0.948815 | 0.975627 | |

| 0.978035 | 0.976378 | 0.968159 | 0.959398 | 0.949988 | 0.942387 | 0.970942 | 0.978192 | 0.981803 | 0.979274 | 0.970615 | 0.955840 | 0.948815 | 0.975627 | |

| 0.978067 | 0.976383 | 0.968155 | 0.959401 | 0.949988 | 0.942385 | 0.970956 | 0.978194 | 0.981804 | 0.979276 | 0.970617 | 0.955843 | 0.948815 | 0.975628 | |

| 0.977797 | 0.981215 | 0.978636 | 0.969898 | 0.955040 | 0.948397 | 0.975091 | 0.965780 | 0.965329 | 0.958496 | 0.946306 | 0.925542 | 0.906115 | 0.957432 | |

| 0.977791 | 0.981213 | 0.978637 | 0.969897 | 0.955041 | 0.948396 | 0.975088 | 0.965324 | 0.965132 | 0.958274 | 0.946106 | 0.925353 | 0.905947 | 0.957122 | |

| 0.977791 | 0.981213 | 0.978637 | 0.969897 | 0.955041 | 0.948396 | 0.975088 | 0.965304 | 0.965104 | 0.958249 | 0.946084 | 0.925330 | 0.905920 | 0.957099 | |

| 0.977793 | 0.981213 | 0.978638 | 0.969896 | 0.955044 | 0.948396 | 0.975089 | 0.965339 | 0.965113 | 0.958252 | 0.946079 | 0.925340 | 0.905960 | 0.957118 | |

| 0.977791 | 0.981211 | 0.978636 | 0.969895 | 0.955041 | 0.948397 | 0.975087 | 0.965258 | 0.965062 | 0.958206 | 0.946044 | 0.925314 | 0.905983 | 0.957062 | |

| 0.977789 | 0.981211 | 0.978635 | 0.969895 | 0.955040 | 0.948397 | 0.975087 | 0.965227 | 0.965033 | 0.958178 | 0.946018 | 0.925291 | 0.905981 | 0.957034 | |

| 0.977793 | 0.981213 | 0.978638 | 0.969896 | 0.955044 | 0.948397 | 0.975089 | 0.965305 | 0.965105 | 0.958246 | 0.946075 | 0.925341 | 0.905980 | 0.957102 | |

| 0.984083 | 0.986868 | 0.981204 | 0.970437 | 0.949994 | 0.933418 | 0.978475 | 0.971016 | 0.972262 | 0.967195 | 0.956613 | 0.938178 | 0.922365 | 0.965031 | |

| 0.981578 | 0.984560 | 0.978940 | 0.968185 | 0.948245 | 0.931837 | 0.976164 | 0.970660 | 0.972115 | 0.967051 | 0.956487 | 0.938074 | 0.922239 | 0.964802 | |

| 0.981578 | 0.984570 | 0.978937 | 0.968178 | 0.948243 | 0.931810 | 0.976163 | 0.970659 | 0.972109 | 0.967043 | 0.956480 | 0.938067 | 0.922232 | 0.964797 | |

| 0.981914 | 0.984635 | 0.978871 | 0.968004 | 0.947865 | 0.930293 | 0.976208 | 0.970723 | 0.972069 | 0.966998 | 0.956421 | 0.938029 | 0.922214 | 0.964800 | |

| 0.982056 | 0.984944 | 0.979322 | 0.968553 | 0.948586 | 0.931386 | 0.976551 | 0.970735 | 0.972092 | 0.967031 | 0.956461 | 0.938081 | 0.922292 | 0.964825 | |

| 0.981960 | 0.984816 | 0.979192 | 0.968394 | 0.948371 | 0.931052 | 0.976419 | 0.970731 | 0.972086 | 0.967025 | 0.956454 | 0.938069 | 0.922274 | 0.964819 | |

| 0.982074 | 0.984986 | 0.979396 | 0.968688 | 0.948834 | 0.931990 | 0.976634 | 0.970738 | 0.972093 | 0.967030 | 0.956458 | 0.938076 | 0.922280 | 0.964826 | |

| 0.964932 | 0.964332 | 0.957661 | 0.945062 | 0.924328 | 0.906373 | 0.956526 | ||||||||

| 0.964320 | 0.963973 | 0.957260 | 0.944642 | 0.923871 | 0.905896 | 0.956035 | ||||||||

| 0.964284 | 0.963898 | 0.957185 | 0.944566 | 0.923809 | 0.905858 | 0.955979 | ||||||||

| 0.964377 | 0.963854 | 0.957090 | 0.944448 | 0.923693 | 0.905891 | 0.955975 | ||||||||

| 0.964389 | 0.963877 | 0.957124 | 0.944490 | 0.923749 | 0.905977 | 0.956002 | ||||||||

| 0.964387 | 0.963874 | 0.957123 | 0.944489 | 0.923742 | 0.905964 | 0.955999 | ||||||||

| 0.964392 | 0.963880 | 0.957123 | 0.944486 | 0.923739 | 0.905952 | 0.956002 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Girolimetto, D. Non-Negative Forecast Reconciliation: Optimal Methods and Operational Solutions. Forecasting 2025, 7, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040064

Girolimetto D. Non-Negative Forecast Reconciliation: Optimal Methods and Operational Solutions. Forecasting. 2025; 7(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirolimetto, Daniele. 2025. "Non-Negative Forecast Reconciliation: Optimal Methods and Operational Solutions" Forecasting 7, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040064

APA StyleGirolimetto, D. (2025). Non-Negative Forecast Reconciliation: Optimal Methods and Operational Solutions. Forecasting, 7(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040064