1. Introduction

Retail structured products are flexible investment instruments which give retail investors the opportunity to get access to customized payoff profiles in a simple way. Serving as an alternative for direct investments, retail structured products are bearer bonds issued by financial institutions typically packaging derivatives that create these special risk profiles. In Germany alone, one of the largest markets for retail structured products in the world, the current outstanding market volume amounts to around EUR 67 billion (67.3 billion Euros in Q2 2020, Deutscher Derivate Verband (2016) [

1].). Trading of the products is either possible OTC, that is, directly with the issuer, or through a retail exchange such as EUWAX or Börse Frankfurt. In most cases, the provider of liquidity is the issuing institution itself which typically commits to operate as a market maker until maturity. Together with short selling restrictions, this however potentially offers a significant profit opportunity for the issuer.

While early academic papers, such as Reference [

2] or Reference [

3], focus on the US, there also exists a meaningful literature concerning the German market. In the following, we briefly review studies regarding the more conservative investment certificates leaving high risk structured products out (on these, for instance, see References [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]). The first extensive empirical analysis of issuer margins is carried out by Reference [

9] who investigate 906 discount certificates and reverse convertibles on DAX and NEMAX stocks traded in November 2001. Using a replication strategy with suitable EUREX options, the authors find reverse convertibles on DAX (NEMAX) stocks to be priced 3.04% (3.89%) above their theoretical values, while prices of discount certificates presumably include an even larger issuer margin of 4.20% (10.04%) on average. Besides these results, Reference [

9] find evidence for their order-flow hypothesis, which postulates that products are overpriced after issuance when most investors buy, and closer to the fair value when the number of certificates bought and sold is in equilibrium.

Later on, Reference [

10] showed support for their life-cycle hypothesis which claims that issuer margins are earned continuously over the products’ lifetimes, and thus, the overpricing should be higher for certificates with a longer time-to-maturity. Analyzing 2566 equity-linked structured products on the DAX and its constituents available on 10 October 2002, the authors apply the standard option pricing model of Reference [

11] for the embedded plain vanilla and barrier options. Their results indicate that prices of DAX structured products lie on average 2.13% above their model value at issuance, while they are 0.11% lower in the secondary market. To find indication for declining margins as maturity approaches, Reference [

10] regress the relative price deviations on the products’ remaining lifetimes showing statistical significance.

Reference [

12] is the first to address the influence of issuer’s credit risk by comparing different models for the pricing of discount certificates—the (default-free) [

11] setup, the Reference [

13] approach assuming independence between the market and the issuer’s credit quality, and finally a structural model which allows for correlation effects between the two sources of risk. Given a typically negative correlation between the issuer’s credit risk and market returns, it turns out that margins calculated by the Reference [

13] framework are strictly larger than those resulting from the structural model. Assuming the latter to be the more realistic setup, Reference [

12] come to the conclusion that Deutsche Bank prices with the lowest issuer margins (0.67%), followed by UBS (0.84%), Commerzbank (0.91%), BNP Paribas (1.29%) and Société Générale (2.27%).

In a more recent study, Reference [

14] analyzes the order-flow hypothesis for a sample of discount certificates issued on the DAX index between November 2006 and December 2007. Using a Black-Scholes-type implied volatility model adjusted for credit risk, the author finds that margins have decreased to an overall average of 0.42%. As an explanation for these seemingly surprising findings, Reference [

14] refers to an increased volume and a more competitive market. For the more risky path-dependent bonus certificates, Reference [

15] estimates average issuer margins between 1.98% p.a. and 3.50% p.a. after applying the stochastic volatility model of Reference [

16] and incorporating credit risk with the independence approach of Reference [

13]. Furthermore, the study in Reference [

17] (The study in Reference [

17] was supported by the

Deutscher Derivate Verband (DDV), the issuers’ lobby group in Germany.) considers a selected representative and a random sample, each consisting of 200 securities from different product categories, and the authors find a mean issuer margin of 0.36% p.a. and 0.46% p.a., respectively. In addition to credit risk, they include hedging costs in terms of a flat 2% barrier shift for products with barrier features which may explain how they obtain lower issuer margins than Reference [

14].

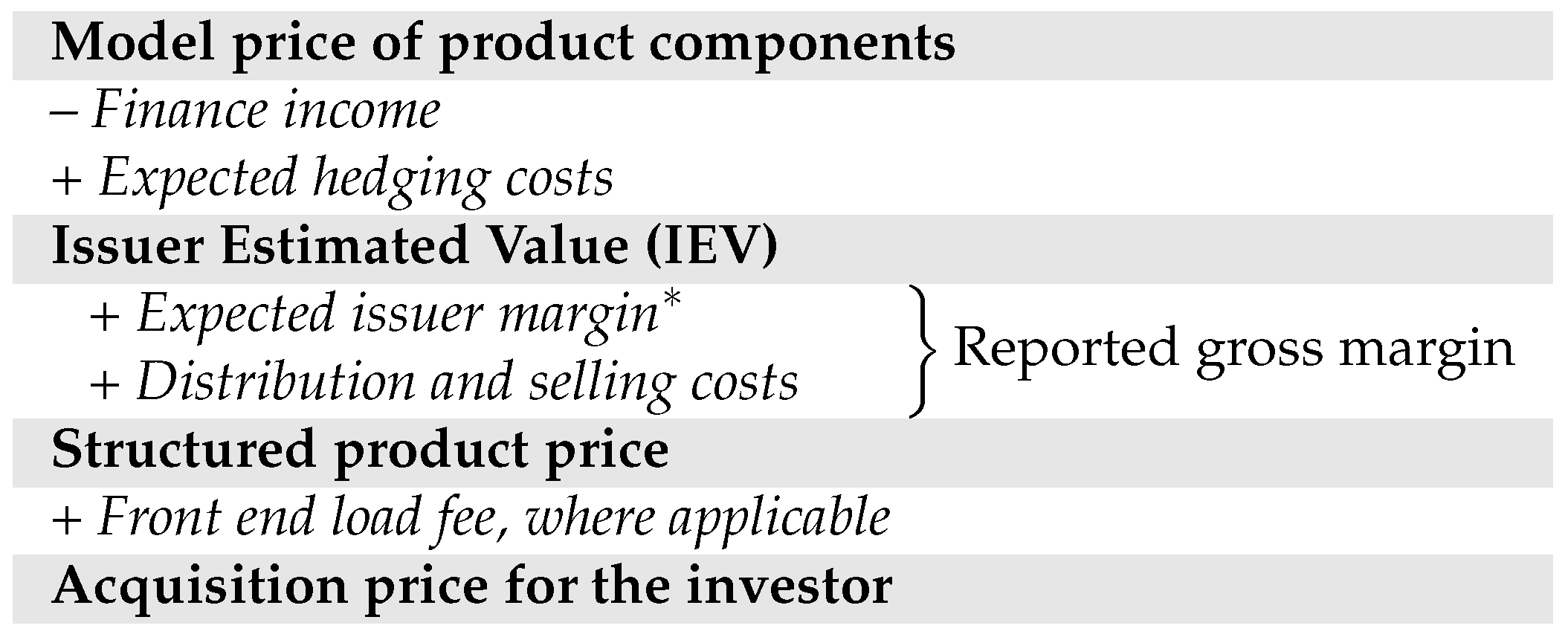

In May 2014, resulting from discussions with regulators and the willingness to offer more transparency for retail clients, the Deutscher Derivate Verband (DDV) and the issuers in Germany established the so-called Issuer Estimated Value (IEV). The IEV is published in the product information sheet and should reflect a fair and market-consistent value of the certificate’s payoffs, which are further adjusted for financing income as the investor acts as a capital provider for the issuer. Additionally, the IEV also accounts for hedging costs which are faced by the issuing banks. From there on, the issuers voluntarily commit to report the IEV of each investment certificate in its respective product information sheet which contains all relevant product features and a scenario analysis [

18]. When banks disclose the IEV at the issue date, they also make an implicit statement on their gross margin which is the difference between the Issuer Estimated Value and the issue price typically expressed as percentage number. The gross issuer margin contains the bank’s expected (To improve legibility, we often drop the word “expected.” However, throughout the study, all gross issuer margins relate to expected profits which are not necessarily realized [

17].) profits but also costs of distribution and selling.

Figure 1 summarizes the definition of the Issuer Estimated Value and its price components as outlined by the DDV.

Since then, to the best of our knowledge, there have only been a few studies who analyzed the fairness and market-consistency of the reported gross issuer margins—a gap we would like to continue closing with this paper. In particular, we focus on discount and capped bonus certificates, two important subclasses which account for about 11.7% of total outstanding volume and 29.7% of the total monthly trading volume in Germany (see Reference [

1]). These two types of certificates due to their widespread availability and prominence have also been part of recent studies on diversification strategies for retail investors (see, e.g., Reference [

19]). More complex products like autocallables are left for future research as there is still an ongoing academic debate which pricing models suit these specific payoffs best (see, e.g., Reference [

20]).

On assessing the fairness of the reported gross margins, our present study should be considered together with Reference [

21], who collected published IEVs of DAX certificates and stressed various difficulties when trying to validate the issuer’s pricing models and with Reference [

22] who carried out a similar analysis as the present paper, however focusing just on discount certificates. Although, in 2018 the IEV has been replaced by similar margin and cost information due to the newly introduced Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Investment Products Regulation, we believe that a study of the correctness and consistency of these values might still be a fruitful guide when considering these new statements. We will discuss this further in the conclusion.

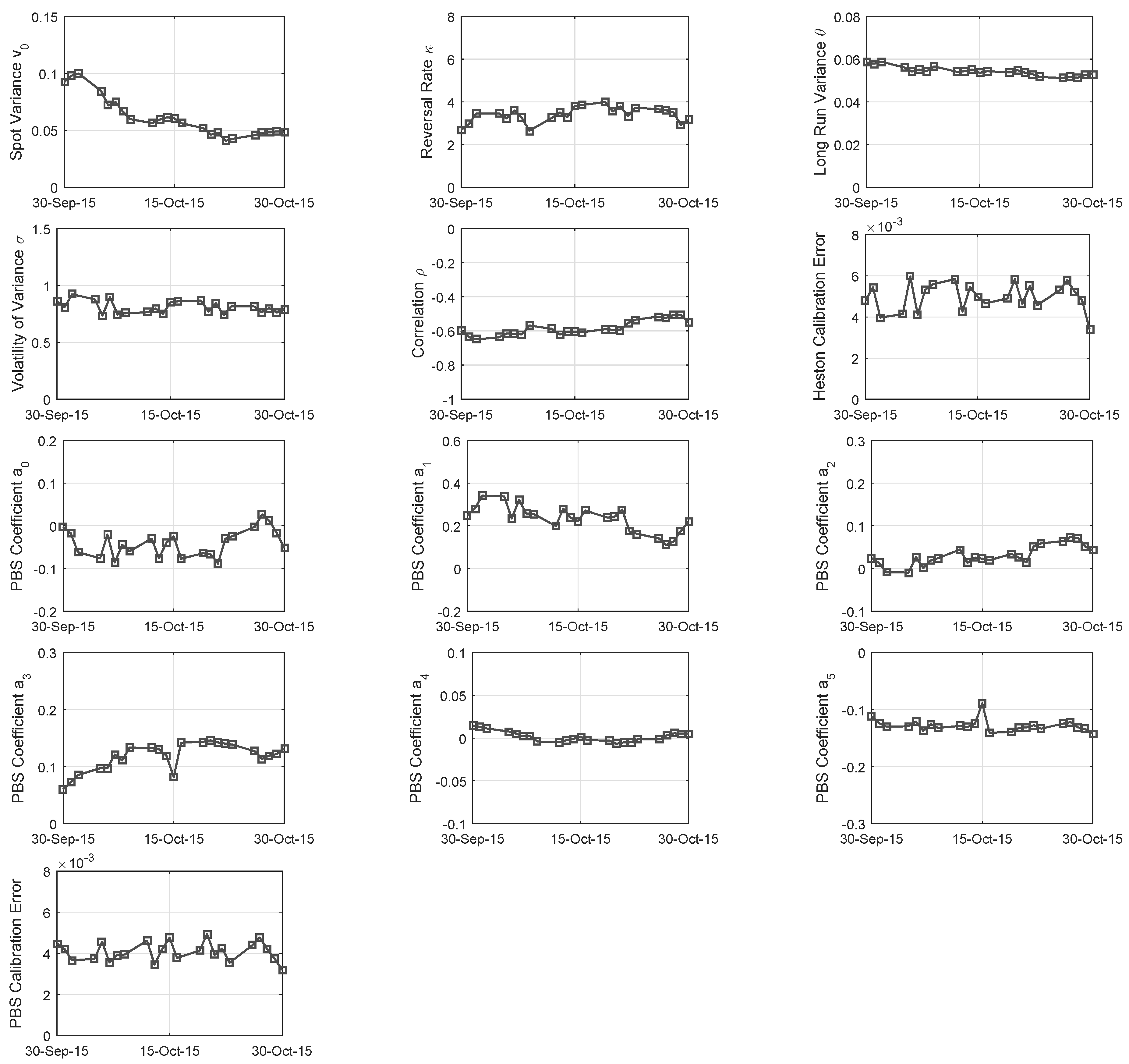

To reduce pricing uncertainty arising from illiquid hedging instruments and different approaches of estimating dividend yields, we focus on the DAX performance index as the underlying security. For each product, we compare two numbers at the day of issuance: first, we derive the reported gross margin from the issue price and IEV, and, in a second step, compare this figure to a model-based gross margin computed from the first end-of-day ask price and an end-of-day model value. This procedure solves issues regarding the lack of information about the exact time of day when the IEV was derived. In total, we obtain a sample of 714 structured products issued between 30 September and 31 October 2015. In line with the recent studies of References [

14,

15,

17], we rely on two Black-Scholes-type pricing approaches using implied volatility surfaces and the stochastic volatility framework of Reference [

16]. Default risk will be incorporated through the Reference [

13] approach, but we will apply a flat adjustment of the individual issuer’s CDS to account for credit/equity correlation. To incorporate hedging costs, we include a barrier shift and consider bid-ask spreads of traded options. Furthermore, we assess the robustness of our results with respect to different assumptions of such hedging adjustments and therefore mitigate pricing uncertainties ([

21]).

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows—

Section 2 describes the selection procedure of discount and capped bonus certificates for the empirical analysis. Afterwards, we provide descriptive statistics of reported gross margins resulting from IEVs in the product information sheets. Then,

Section 4 introduces the applied pricing frameworks explaining in detail how model parameters are calibrated and hedging costs applied, before we present the results of our empirical analysis in

Section 5, and robustness tests in

Section 6. The paper closes with a conclusion summarizing our main findings.

2. Data Selection

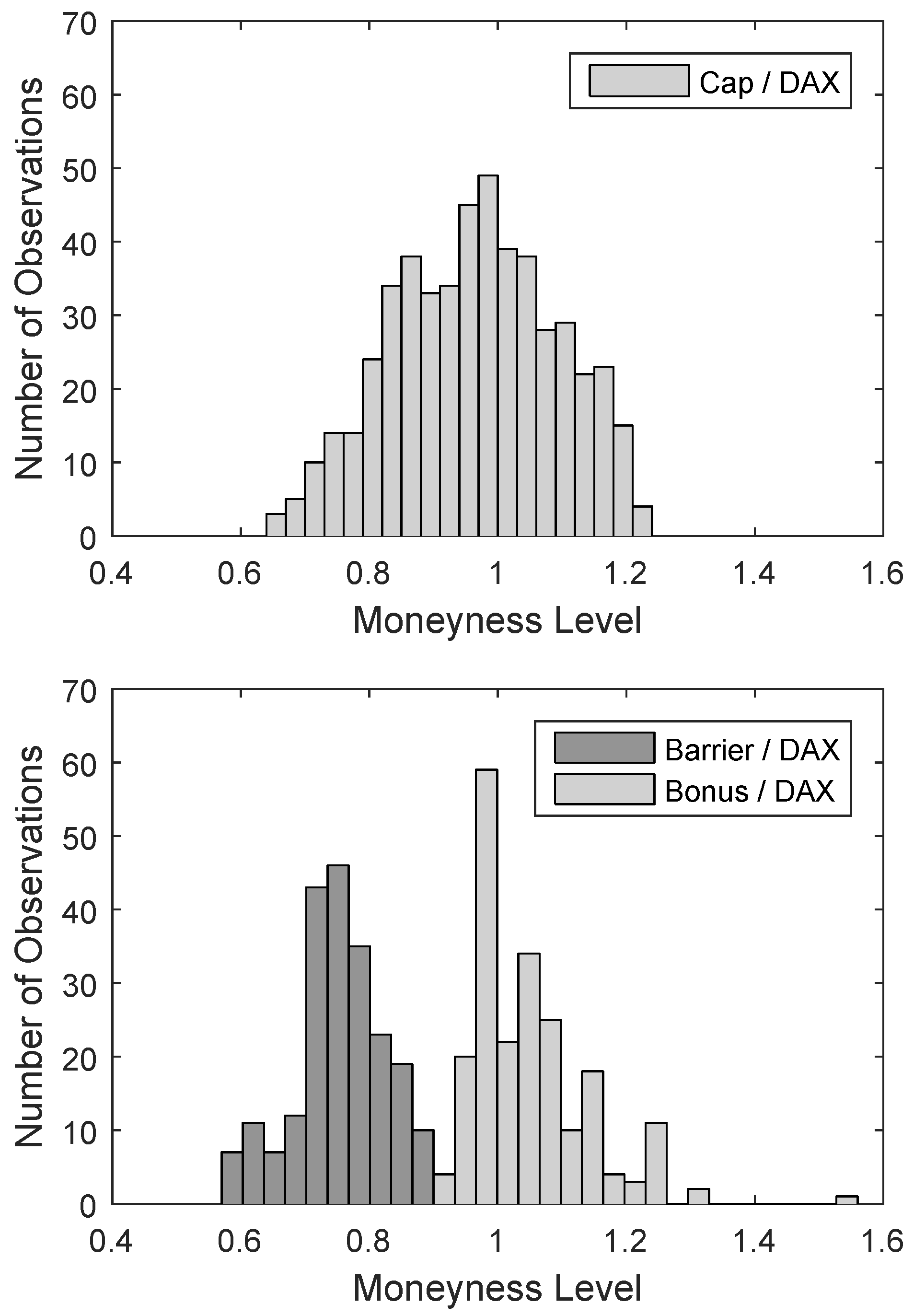

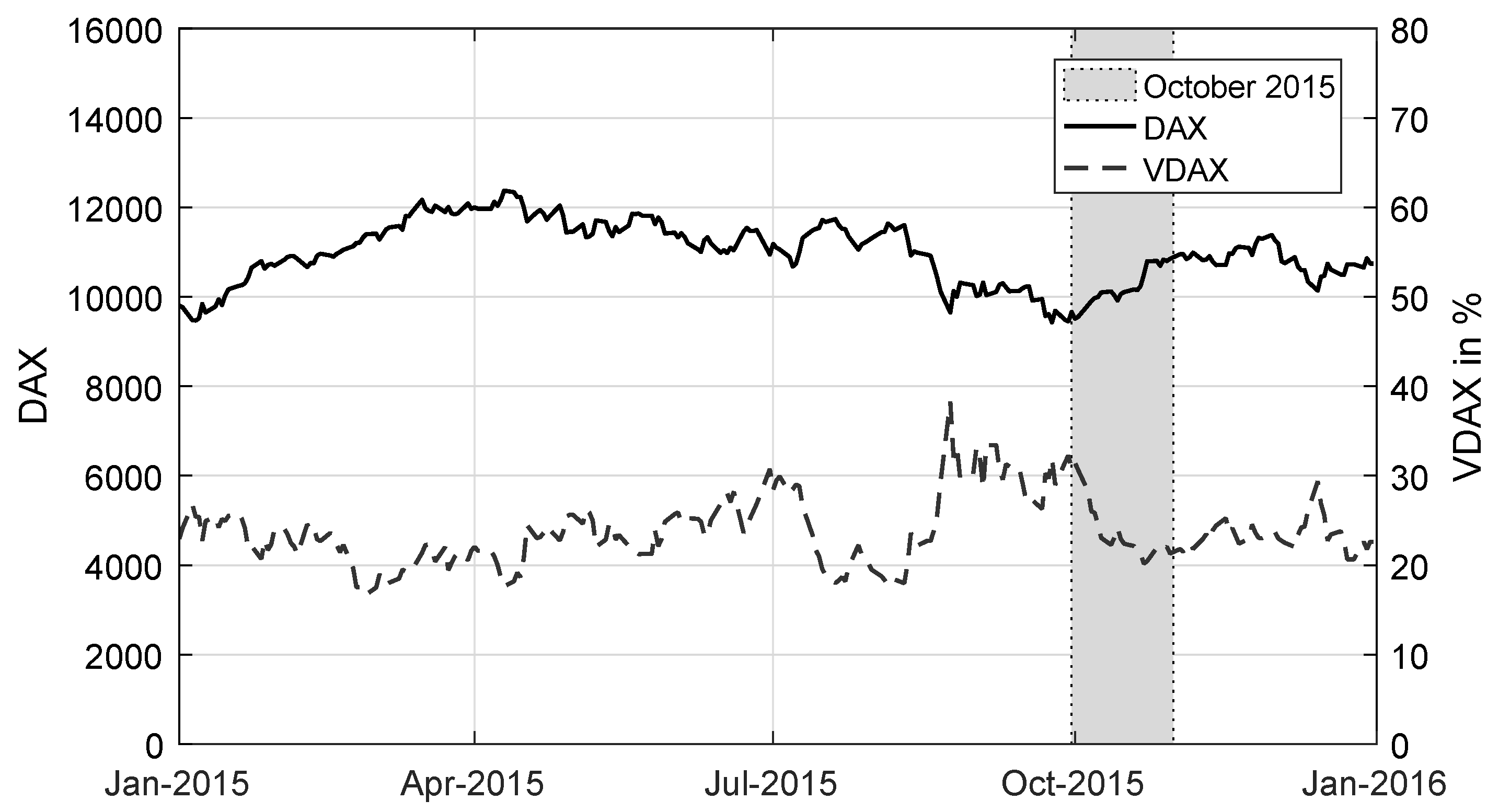

To assess the fairness and market-consistency of reported gross issuer margins, we focus on discount and capped bonus certificates which represent two important subclasses of retail structured products. In the following, we consider DAX index certificates issued between 30 September and 30 October 2015, a timeframe that can be characterized as a calm market period as illustrated in

Figure 2. For data collection, we use OnVista, a website providing structured product selection tools and containing all exchange-listed products. Taking all securities in the mentioned product categories and the timeframe into account, we arrive at 1504 discount and 3208 capped bonus certificates in a first step.

To achieve more homogeneity of the certificates’ characteristics and ensure the availability of actively traded derivatives at EUREX for model calibration, we only consider products with lifetimes larger than 3 and smaller than 24 months. We further filter by maturity and identify timeframes in which at least two issuers are present with more than five single products that have a (nearly) similar counterpart from another issuer. Additionally, we only consider products expiring on quarterly dates as they usually offer a more liquid hedging market. For discount certificates, these timeframes are June–August, October–November 2016, February–March and September 2017. And correspondingly, for capped bonus certificates, these periods are March, June, December 2016 and March 2017. Finally, this selection procedure yields a data set with 501 discount and 259 bonus certificates issued from eight different banks. Specifically, the data set contains discount certificates issued by Commerzbank (), HSBC (), Citigroup (), DZ Bank (), Vontobel (), Goldman Sachs () and BNP Paribas ().

In the subsample of capped bonus certificates, we have securities from DZ Bank (), BNP Paribas (), Deutsche Bank (), Goldman Sachs () and Vontobel (). Note that the 46 capped bonus certificates of HypoVereinsbank (HVB) have to be dropped from the final data set as HVB did not provide any product information sheets with Issuer Estimated Values during October 2015. Finally, closing bid and ask quotes are obtained from the EUWAX exchange for all 714 structured products at the respective day of issuance, 5:30 p.m. Frankfurt time. Issuer Estimated Values, product issue prices and dates are extracted from the product information sheets downloaded from each bank’s webpage.

3. Reported Gross Margins and Product Lifetimes

In the following, we take reported Issuer Estimated Values from product information sheets and put them in a relation to issue prices to deduce the reported gross issuer margin for each product. To obtain a more balanced panel, we divide the reported gross margin by the time-to-maturity

T to obtain an annualized figure which is specifically defined as

Table 1 provides summary statistics of the reported annualized gross margins and product lifetimes for the overall data set (

) and throughout this paper, only annualized gross margins are considered. In total, the reported gross margins are on average 0.61% p.a. and the mean time-to-maturity is 1.19 years.

In the subsample of discount certificates, the mean reported gross margin at issue date is 0.40% p.a. and securities expire on average 1.31 years after issuance. These reported issuer margins are of the same magnitude as those obtained before by the earlier academic papers, for example, References [

14,

17], who derive 0.42% (0.39%) p.a. for discount certificates, respectively. Although any comparison across banks should be treated with care as the products’ characteristics may deviate, Vontobel seems to offer discount certificates with the highest gross margins ranging from 1.38% p.a. up to 2.20% p.a. Furthermore, DZ Bank reports the lowest gross margin with at most 0.02% p.a. of the product price with an average time-to-maturity of 1.57 years.

For the subsample of 213 capped bonus certificates, reported gross issuer margins range from 0.02% p.a. to 3.51% p.a. with an average of 1.10% p.a. and 0.91 years mean time-to-maturity—notably shorter than discount certificates. The reported margins are in accordance with the magnitude derived by Reference [

17] who obtain a result of 0.90% p.a. for capped bonus certificates at the date of issuance. In our sample, BNP Paribas reports highest gross margins ranging from 2.28% p.a. to 3.51% p.a., while DZ Bank states the lowest charges with 0.20% p.a. on average. Overall, for both discount and capped bonus certificates, we find a notable heterogeneity of reported gross margins across issuers even after ensuring that the products have similar characteristics. Nevertheless, margin discrepancies across issuers can also be explained by different interpretations of the IEV standard which does not state explicit guidelines on the pricing methods and specification of hedging costs. In particular, the fairness code [

18] mentions trading costs and bid-ask spreads as potential cost of hedging. As earlier papers do not account for any of these expenses, we incorporate hedging costs in our pricing methodology in terms of the options’ bid-ask spread which issuers are facing when hedging the derivative components. The detailed procedure is explained in the following.

6. Robustness

Following the definition, the Issuer Estimated Value consists of a model price of the product components adjusted for finance income and hedging costs. Nevertheless, the definition of hedging costs in particular has weak points as the fairness code only states it includes “trading costs or bid-ask spreads” [

18], which are not specified any further. In this study, however, we try to closely follow the definitions while revealing the technical pricing process with all related assumptions as transparent as possible. However, the consideration of hedging costs in terms of a volatility charge for short call options of 0.62% as shown in

Section 4.7 potentially drives the results of our empirical study.

To address these concerns, we repeat the pricing procedure and systematically vary the inputs accounting for the occurring hedging costs while leaving all other assumptions fixed. As shown in

Section 5, the impact of the pricing model does not play a noteworthy role for discount certificates and the Heston model is the most suitable model for pricing barrier features—thus, we only report results for the Heston model in this robustness analysis. In the following, we consider four different scenarios: firstly, we have the default assumption of the volatility charge of 0.62% that is derived from the median bid-ask spread of EUREX call options in the prior month September 2015. Then, we regard two variations of this number where we increase (decrease) the volatility charge by 30% to 0.81% (0.43%) to illustrate the impact of a different input at this place. Finally, we also implement the case of a zero volatility charge. For an illustration of the impact of hedging costs, we derive the relative contribution of the volatility change (RCoVC) by the percentage reduction of the gross margin when a volatility change is applied. This means we compare the Heston gross margin derived with a volatility charge to those computed without any.

For discount certificates,

Table 5 shows summary statistics of gross margins derived from the Heston model with varying assumptions (+0%, −30%, +30% and −100%) on the default volatility charge of 0.62%. Same as in

Table 2, these figures can be compared to the reported values. In total, we find that a 30% increase or decrease of the volatility charge does not change the conclusions made in the result

Section 5. For instance, a 30% higher volatility charge decreases the overall Heston gross margin from 0.53% p.a. to 0.46% p.a., and vice versa, a 30% reduction yields an overall mean annualized Heston gross margin of 0.60%. The effect on Heston gross margins is similar across individual issuers. In case when no volatility charge is considered, then the average overall Heston gross margin rises to 0.77% p.a. However, as argued in

Section 4, the issuer likely faces some sort of hedging costs and the 0.77% can be considered as an upper bound on the results for the Heston model.

Regarding the capped bonus certificates, we find a similar impact of volatility charge variations on the Heston gross margins as we observed for the discounters. As shown in

Table 6, we find that a 30% increase of the hedging costs arising from trading the call option leads to an average Heston gross margin of 1.28% while a 30% reduction contributes to a 1.42% model-based gross margin. When we do not account for hedging costs occurring when the call option is shorted, then we find an average of 1.58% p.a. In relative terms, a variation of the volatility charge has a slightly smaller effect on the figures for capped bonus certificates as the overall absolute level is higher.

For all products and issuers,

Table 5 and

Table 6 also well-illustrate the strong relative influence of hedging costs on expected gross margins, ranging down to −40% for discounters and −19% for capped bonus certificates. The intuition is that supposed bid-ask spreads from options traded at exchanges, such as the EUREX, can be large in Euro terms and as the issuers gross margin is a small residual on top of some fair value, the effect on gross margins is leveraged. This effect, of course, is larger for certificates with smaller charged gross margins as we can see for the HSBC subsample in

Table 5 where the increased hedging costs shrink the mean gross margin derived from the Heston model by −41%.

7. Conclusions

Individualized payoff profiles and low transaction costs make retail structured products appealing for many private investors. However, as short selling is prohibited and issuers are typically market-makers of these products, high margins can be potentially realized by overpricing as already indicated by several empirical studies. In May 2014, the Deutscher Derivate Verband and issuing banks decided to provide more transparency by disclosing the Issuer Estimated Value, a fair value of the certificates designed to reflect the market price of the product among professionals. By publishing the Issuer Estimated Value, banks implicitly make a statement on their expected gross margin and, as a first paper, we provide an empirical analysis on the fairness and market-consistency of these figures. While in 2018 the IEV has been replaced by similar margin and cost statements, our results should still be a good proxy on these new key figures. We will discuss this in more detail below.

We have several findings—firstly, we deduce that reported gross margins vary considerably across issuers even on standard retail products such as the discount and capped bonus certificates which is a surprising finding in such a competitive market. Secondly, we are able to verify the disclosed gross margins using the stochastic volatility model of Heston, the Practitioner Black-Scholes model and the Nadaraya-Watson approach. Overall, observed discrepancies seem to be essentially insignificant even if the correlation adjustment from

Section 4.7 is omitted. As we are facing a high methodological uncertainty in general, our strategy is to make the pricing process as transparent as possible and to show sensitivities of our main inputs. In particular, additional price components of the Issuer Estimated Value, such as hedging and trading costs, require additional assumptions making the pricing potentially prone to misspecifications. To reduce concerns regarding the incorporation of these hedging costs, we provide robustness tests where the volatility charge is varied. Finally, we find that a ±30% variation of these hedging costs and the choice of the option pricing model do not change our main finding that the plausibility of the bank’s disclosed margins can be validated in our sample.

Therefore the answer to our question raised in the present paper’s title is a careful initial ‘yes’—on the one hand, we are able to verify the stated gross margins pretty closely. Observed deviations can be explained be variations in the pricing models and by the fact that the hedging books of the considered issuers are surely not all the same. That means that due to other transactions (e.g., due to institutional derivative flow) some issuers might be more or less keen to sell retail structured products with certain characteristics (like strike, maturities, etc.) and therefore see their fair value differently. On the other hand, as can be seen by considering that competition in this market has risen over the years and margins have accordingly declined (see the literature overview in the introduction), our observed deviations in the reported margins might still be too large for some readers to accept as consistent and fair. Therefore, future research should focus on larger samples and timeframes than our present initial study.

As mentioned before, the concept of the IEV has been discontinued in 2018 as the new European regulation for Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Investment Products (PRIIPs, see Reference [

36]) already leads to new product information sheets which have to contain information about all costs related to these kind of products. In particular, each information sheet has to specify what kind of absolute and percentage costs are associated with buying a structured product, holding and selling it. If one assumes that an investor holds a discount or a bonus certificate until maturity (which is usually done in these product information sheets), all these kind of costs are usually only of the entry cost type. Therefore, the published numbers directly compare to the products’ gross margins investigated in the present paper. Consequently, using these new disclosures might be a good starting point to extend our research.