Modeling the Mutual Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts Using Multivariate Hawkes Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

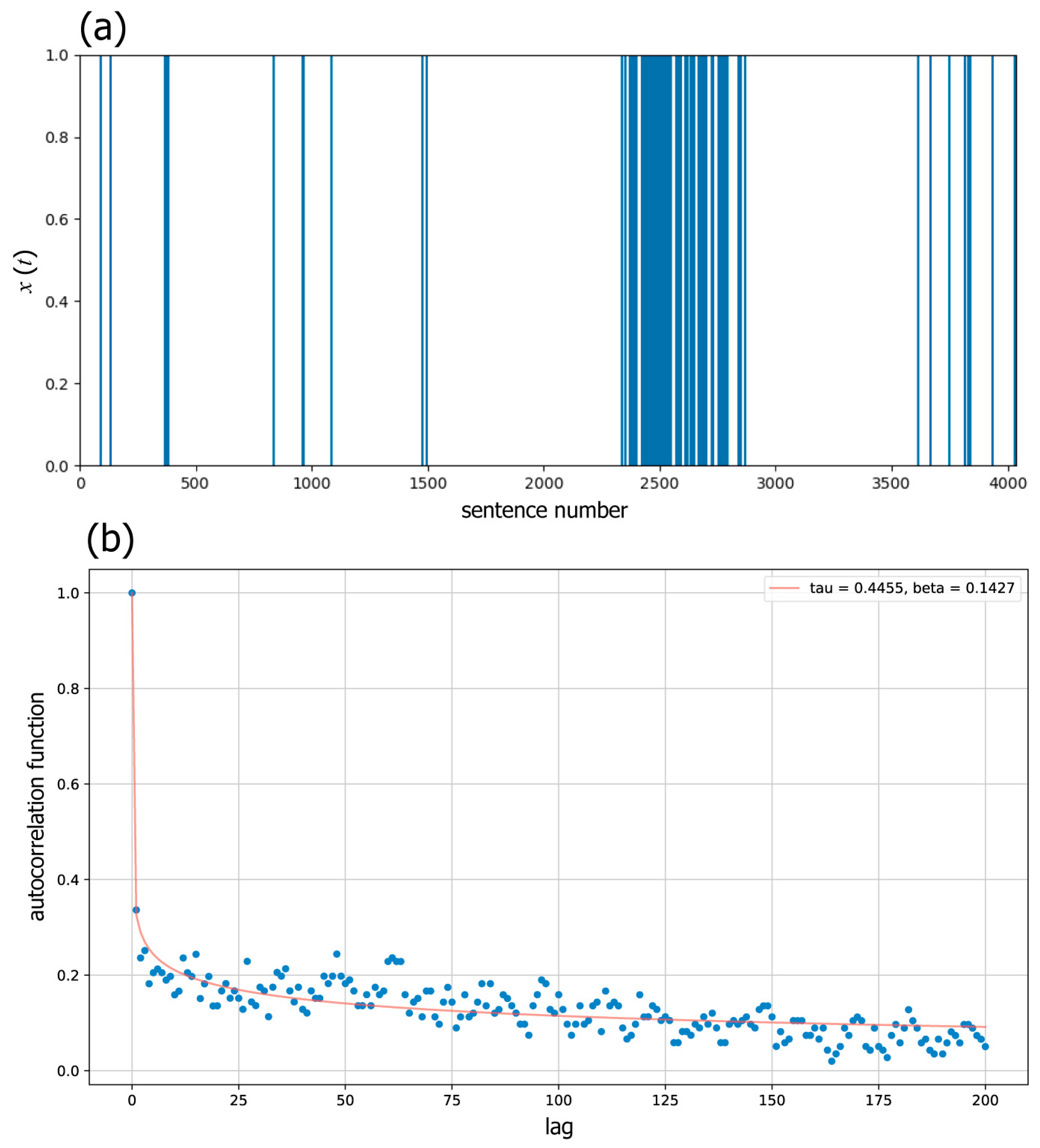

2.1. Converting Text as Time-Series Data

2.2. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Hawkes Processes

2.3. Selecting Important Words in Used Texts

2.4. Validation of Modeling with Hawkes Processes

3. Results and Discussion

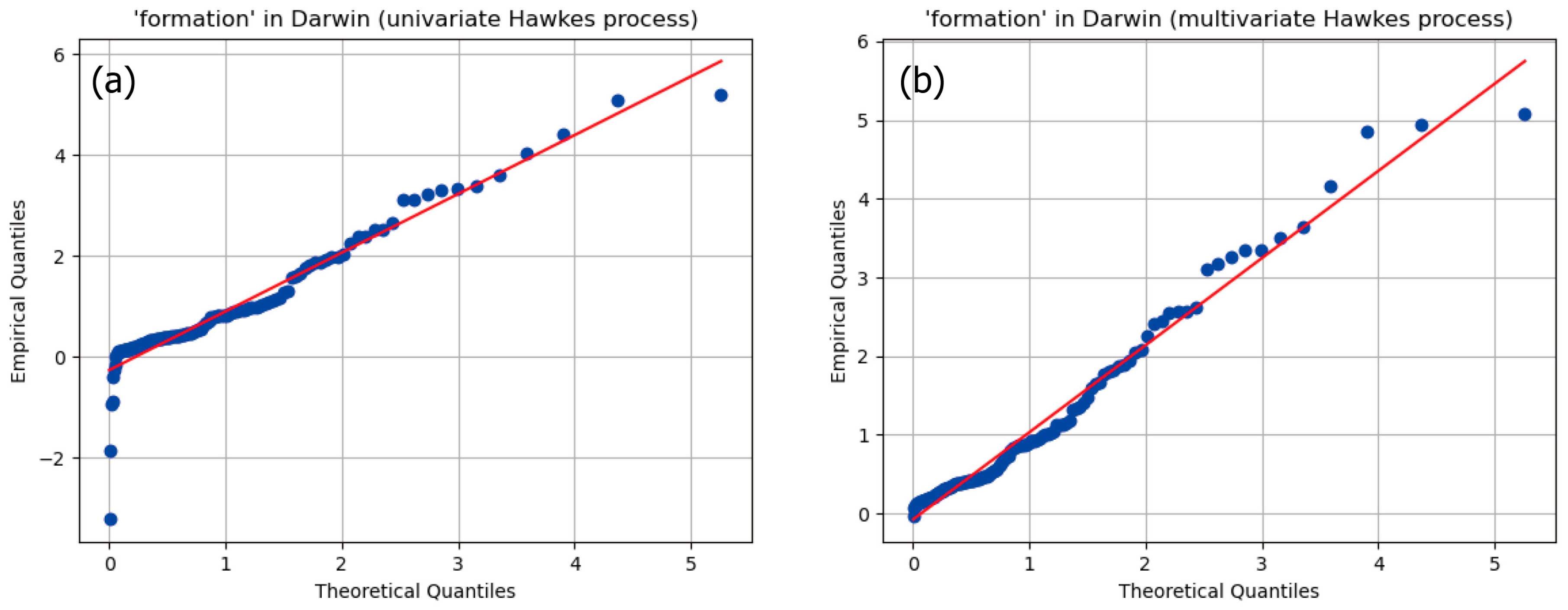

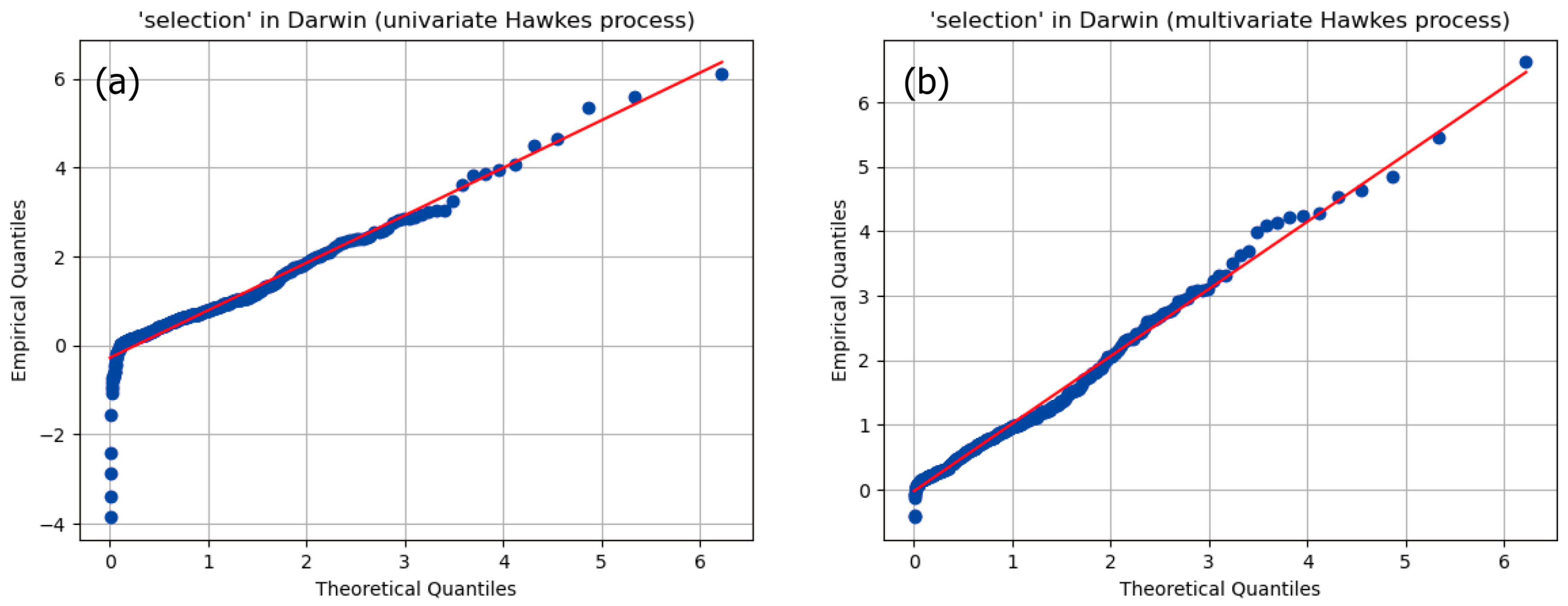

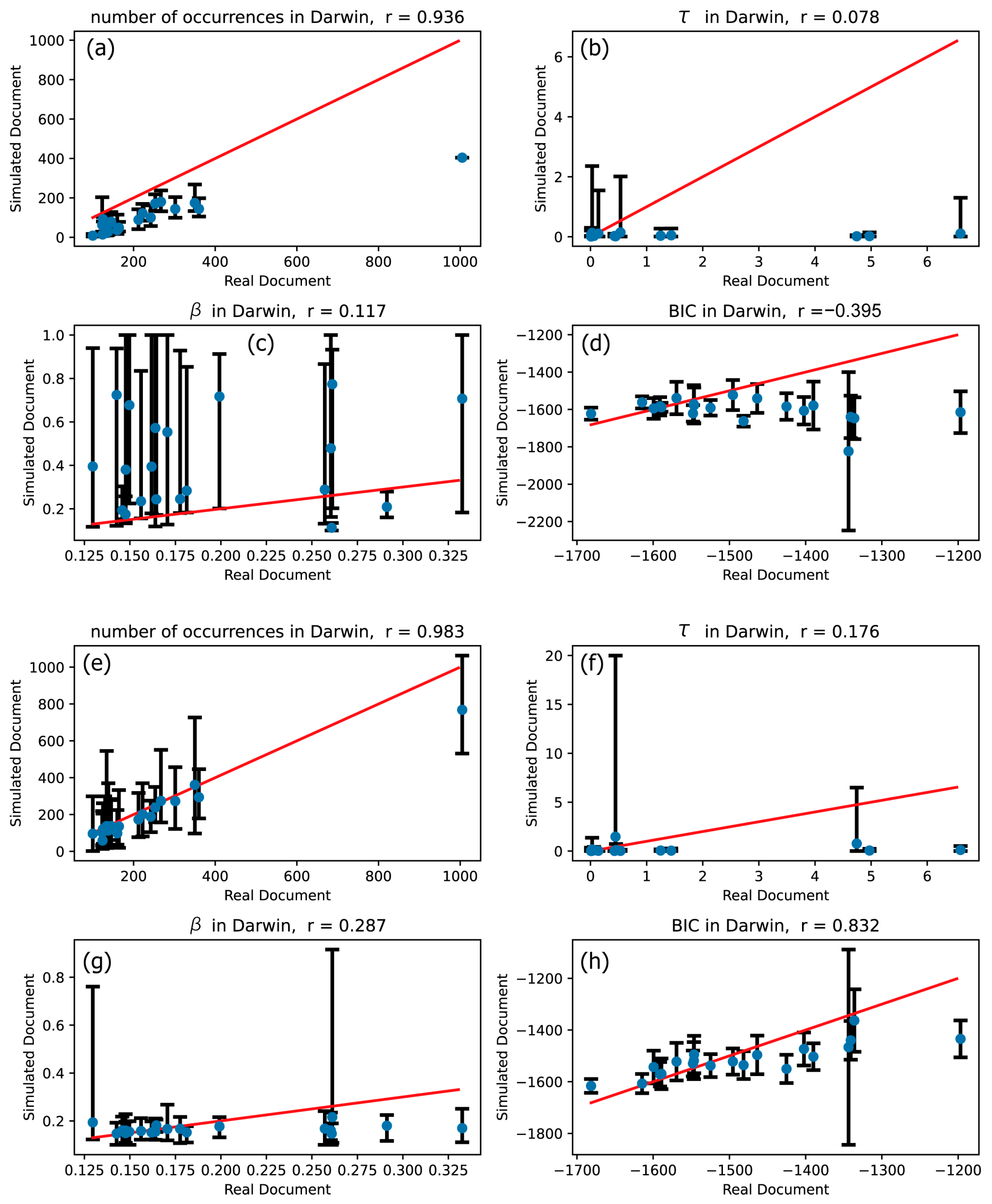

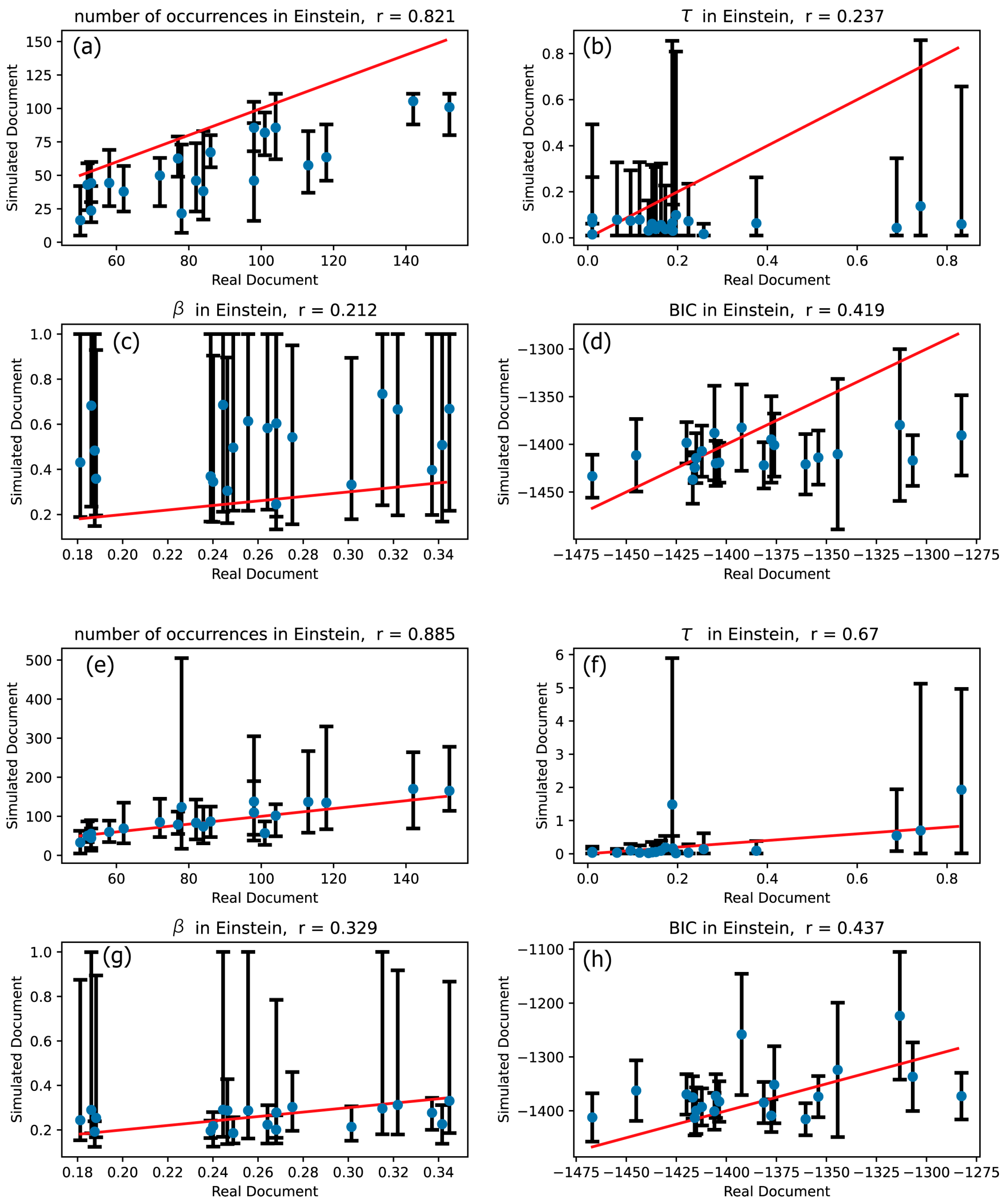

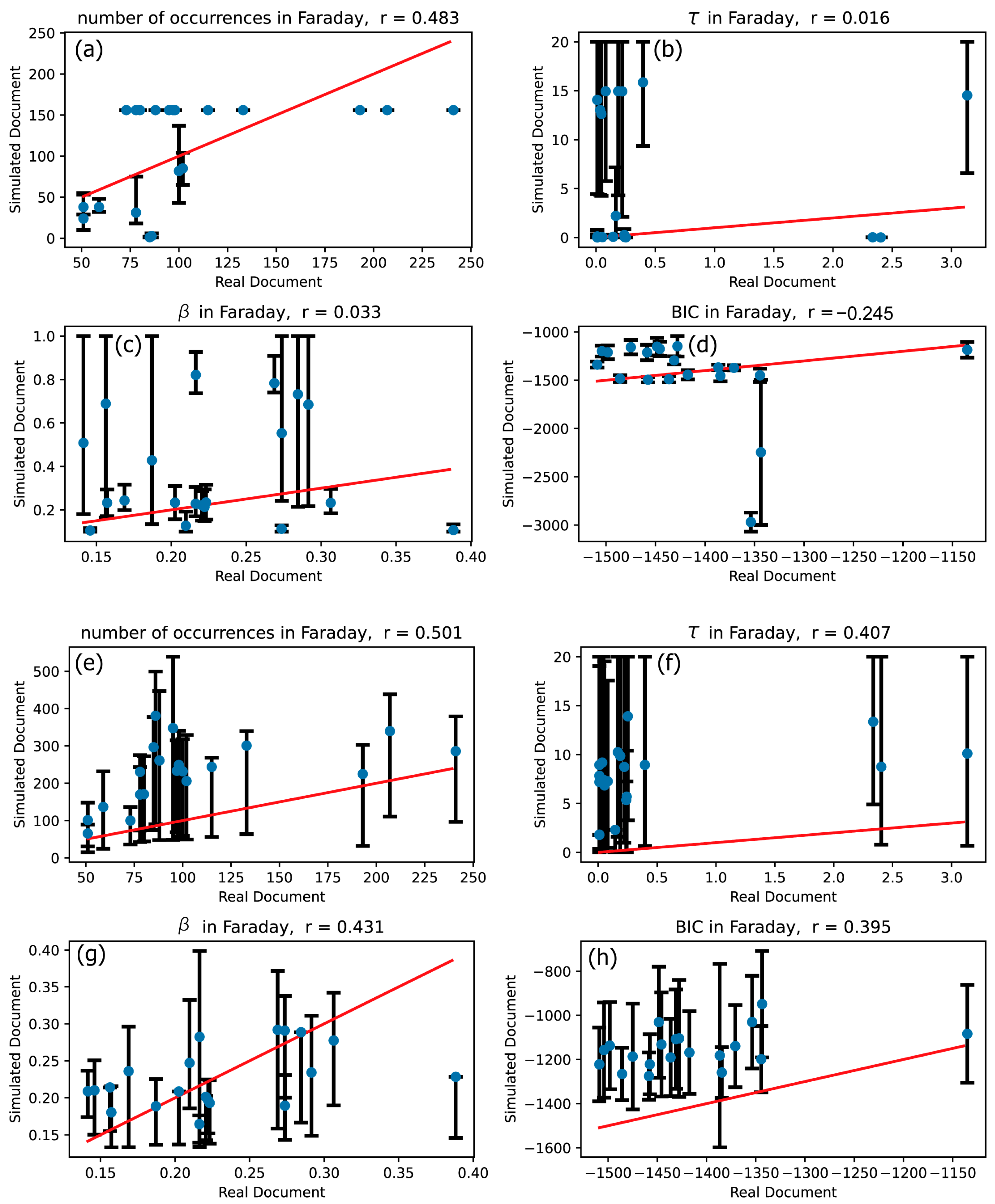

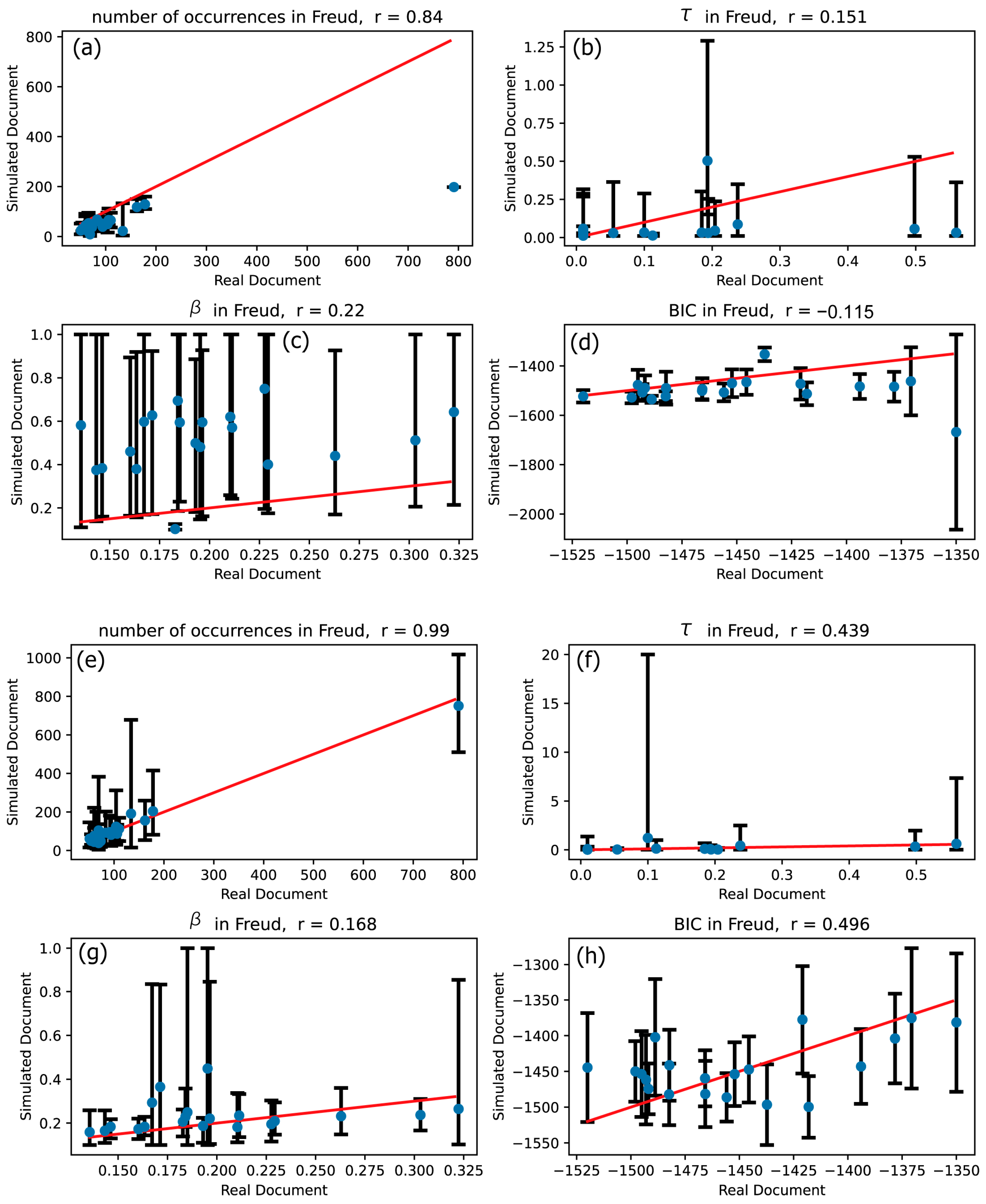

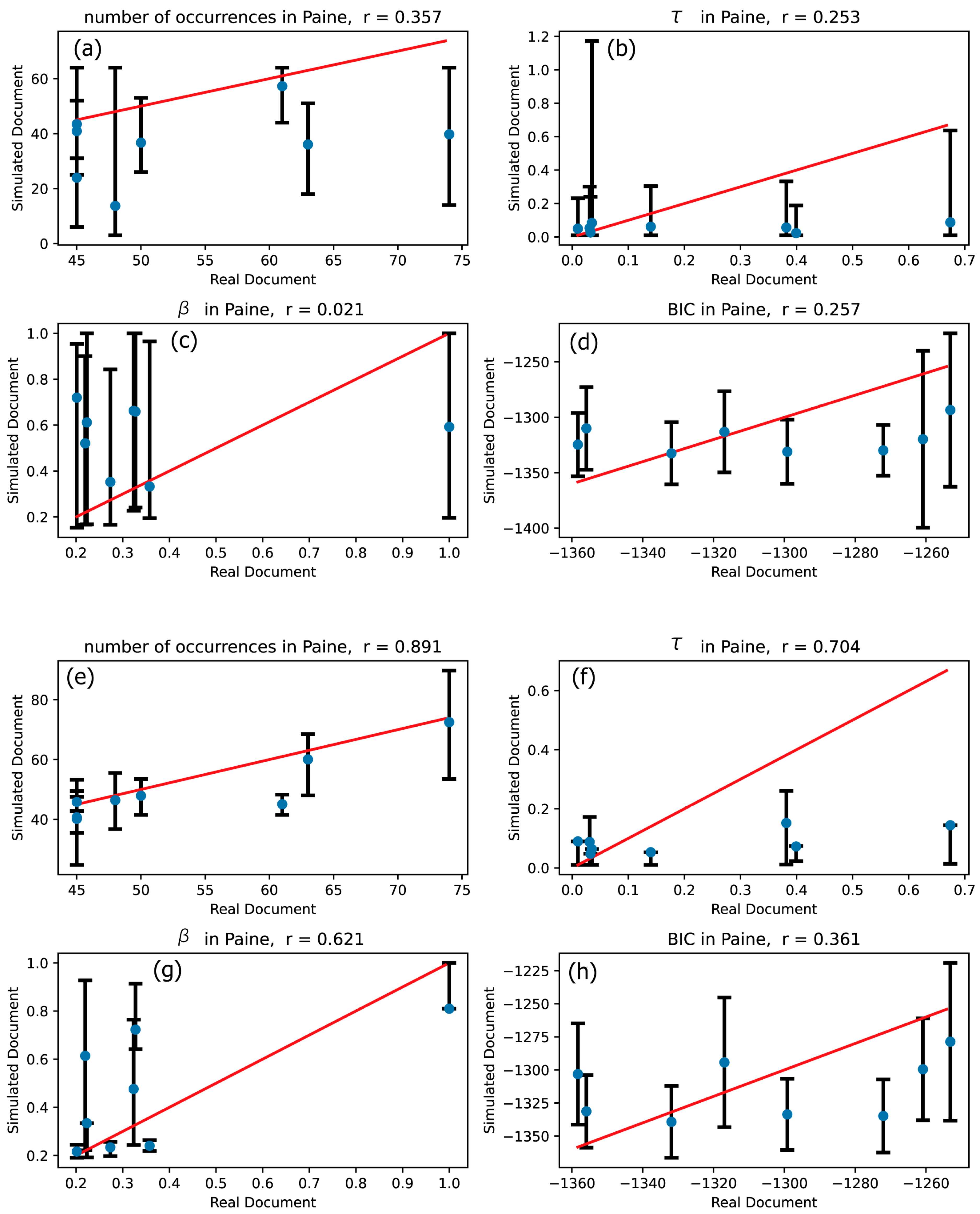

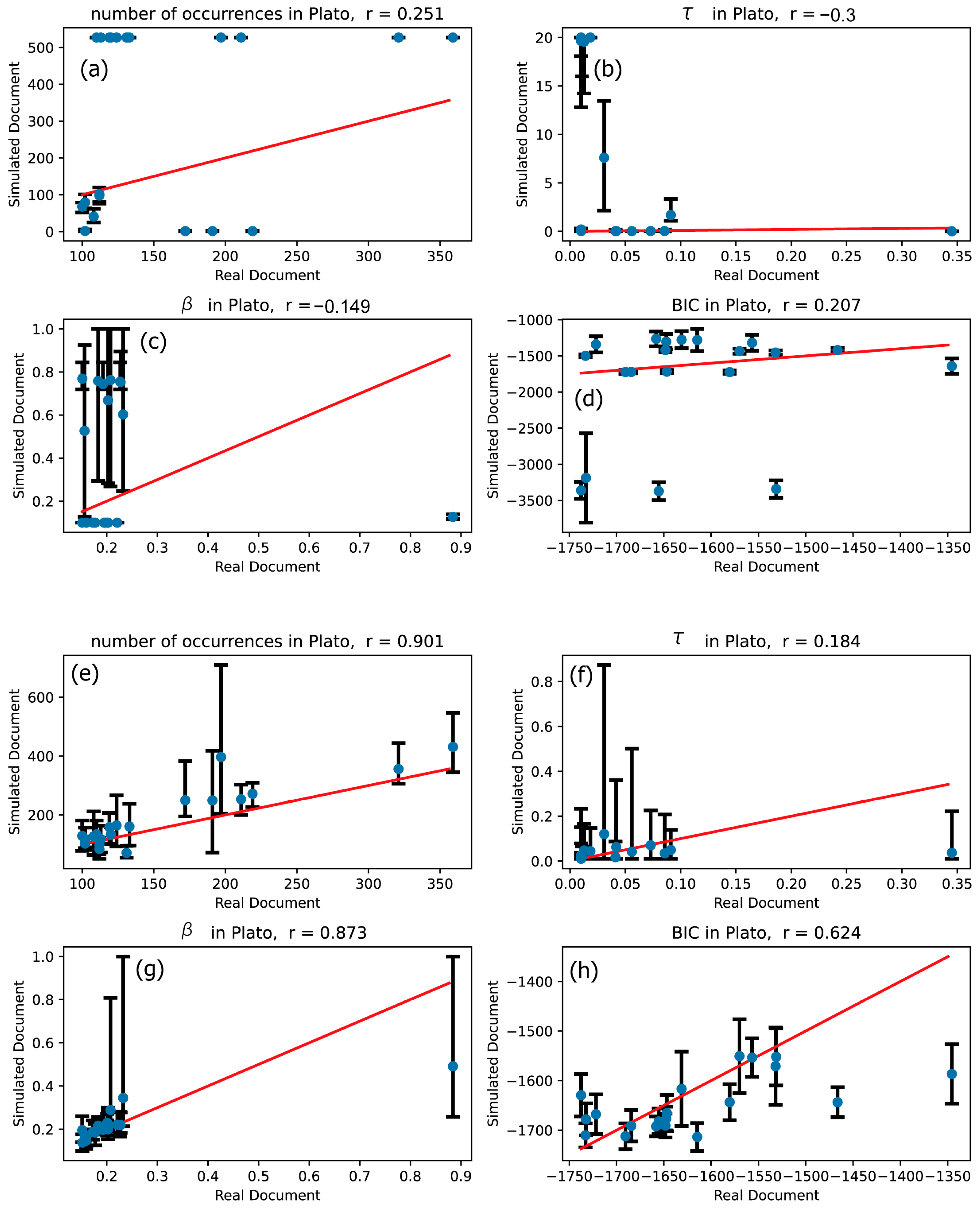

3.1. Validity Confirmation of Hawkes Processes

- The total number of occurrences of the word throughout the text.

- The relaxation time τ of the ACF, derived from the fitting parameter of the KWW function (Equation (9)).

- The shape parameter β of the ACF, also obtained from the fitting parameter of the KWW function.

- The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), calculated during the fitting of the KWW function to ACFs.

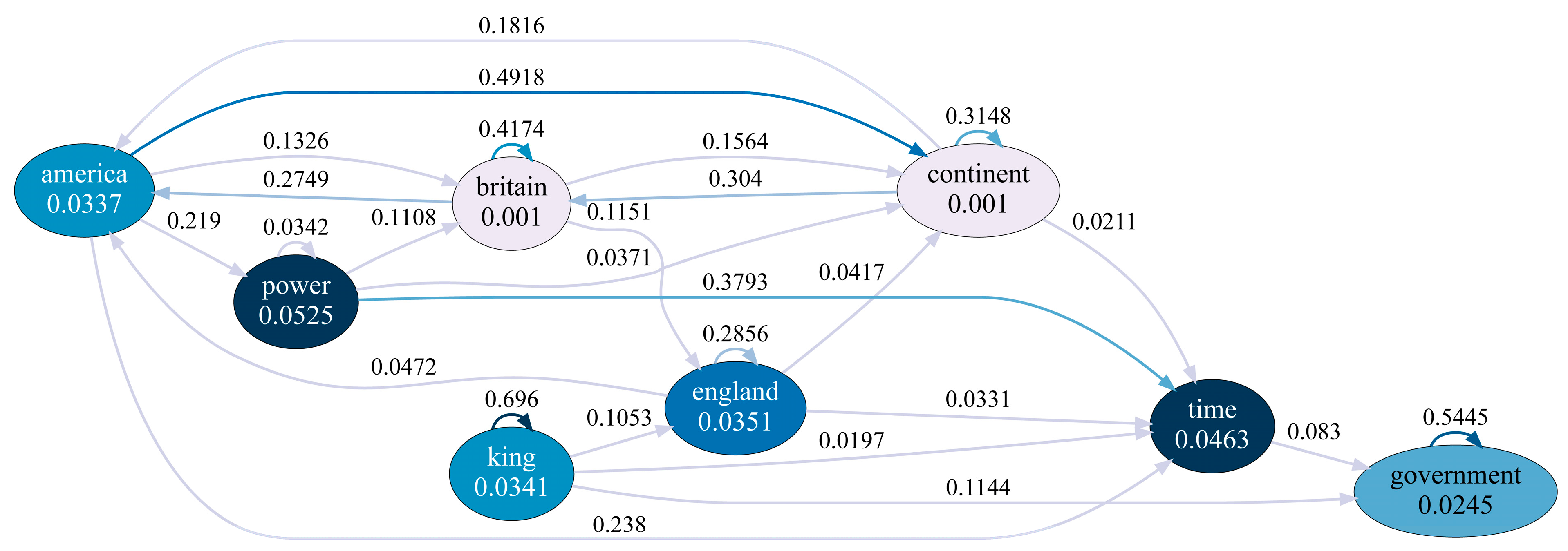

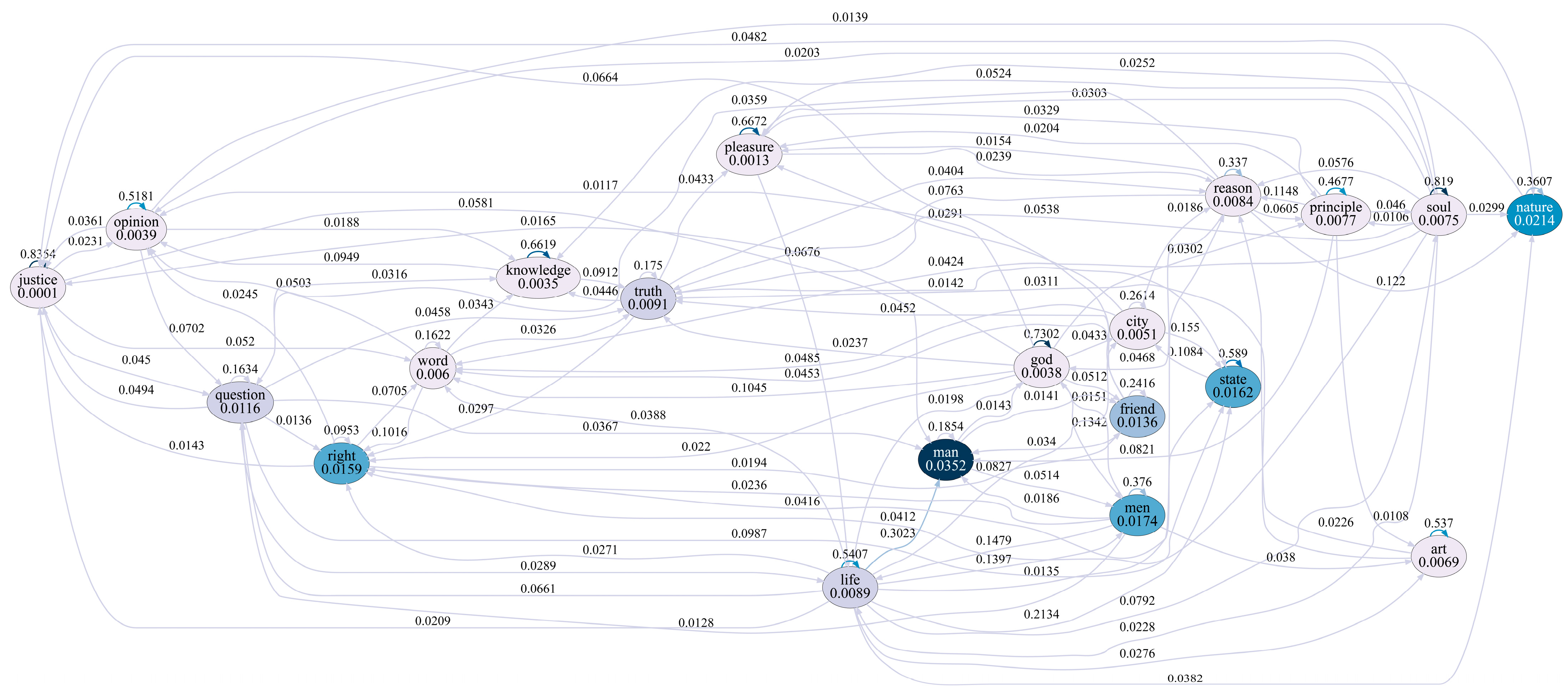

3.2. Hawkes Graphs

3.3. Finding Important Notions in Texts

3.4. Advantages of Analyzing Texts with Multivariate Hawkes Processes

- A Hawkes graph can be generated from the parameter values obtained through the analysis using the multivariate Hawkes process. This facilitates an intuitive understanding of the relationships among the concepts that emerge in the document.

- The importance of each concept identified in a text can be assessed using the optimized parameters of the multivariate Hawkes process. The most significant concepts suggested for each text analyzed in this study are confirmed to be valid when considering the content of the text.

4. Conclusions

- Treating the matrix aij (defined by Equation (11)) as an adjacency matrix and applying graph theory methods, such as spectral clustering.

- Analyzing texts using advanced stochastic processes, such as the autoregressive-type Hawkes process [44]—a discretized variant of the standard Hawkes model—which is particularly well-suited for high-dimensional analyses (e.g., with more than 20 dimensions) due to its lower computational complexity. An alternative promising framework is the “Flexible Triggering Kernels” model [45], which effectively encodes event history and captures localized excitation dynamics beyond traditional decay-based kernels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| ACF | Autocorrelation Function |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| KWW | Kohlrausch–Williams–Watts |

References

- Pawlowski, A. Time-Series Analysis in Linguistics. Application of the Arima Method to Some Cases of Spoken Polish. J. Quant. Linguist. 1997, 4, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, A. Language in the Line vs. Language in the Mass: On the Efficiency of Sequential Modelling in the Analysis of Rhythm. J. Quant. Linguist. 1999, 6, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, A. Modelling of Sequential Structures in Text. In Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 738–750. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski, A.; Eder, M. Sequential Structures in “Dalimil’s Chronicle”; Mikros, G.K., Macutek, J., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, E.G.; Pierrehumbert, J.B.; Motter, A.E. Beyond word frequency: Bursts, lulls, and scaling in the temporal distributions of words. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka-Ishii, K.; Bunde, A. Long-range memory in literary texts: On the universal clustering of the rare words. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Long range correlation in human writings. Fractals 1993, 1, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, W.; Pöschel, T. Entropy and long-range correlations in literary English. Europhys. Lett. 1994, 26, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.A.; Pury, P.A. Long-range fractal correlations in literary corpora. Fractals 2002, 10, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lacalle, E.; Dorow, B.; Eckmann, J.P.; Moses, E. Hierarchical structures induce long-range dynamic correlations in written texts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7956–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, E.G.; Cristadoro, G.; Esposti, M.D. On the origin of long-range correlations in texts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11582–11587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzigeorgiou, M.; Constantoudis, V.; Diakonos, F.; Karamanos, K.; Papadimitriou, C.; Kalimeri, M.; Papageorgiou, H. Multifractal correlations in natural language written texts: Effects of language family and long word statistics. Physica. A 2017, 469, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Amano, H.; Kondo, M. Measuring Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts with an Autocorrelation Function. J. Data Anal. Inf. Process 2019, 7, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Amano, H.; Kondo, M. Origin of Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts. J. Data Anal. Inf. Process. 2019, 7, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Amano, H.; Kondo, M. Simulation of pseudo-text synthesis for generating words with long-range dynamic correlations. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Hanada, Y.; Amano, H.; Kondo, M. A stochastic model of word occurrences in hierarchically structured written texts. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Hanada, Y.; Amano, H.; Kondo, M. Modeling Long-Range Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts with Hawkes Processes. Entropy 2022, 24, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, A.G. Spectra of Some Self-Exciting and Mutually Exciting Point Processes. Biometrika 1971, 58, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y. Statistical models for earthquake occurrences and residual analysis for point processes. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1988, 83, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y. Seismicity analysis through point-process modeling: A review. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1999, 155, 471–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Ogata, Y.; Vere-Jones, D. Stochastic declustering of space-time earthquake occurrences. J. Amer. Statist. Soc. 2002, 97, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truccolo, W.; Eden, U.T.; Fellows, M.R.; Donoghue, J.P.; Brown, E.N. A Point Process Framework for Relating Neural Spiking Activity to SpikingHistory, Neural Ensemble, and Extrinsic Covariate Effects. J. Neurophysiol. 2005, 93, 1074–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynaud-Bouret, P.; Rivoirard, V.; Tuleau-Malot, C. Inference of functional connectivity in Neurosciences via Hawkes processes. In Proceedings of the 1st IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing, Austin, TX, USA, 3–5 December 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, F.; Deger, M.; Truccolo, W. On the stability and dynamics of stochastic spiking neuron models: Nonlinear Hawkes process and point process GLMs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacry, E.; Mastromatteo, I.; Muzy, J. Hawkes Processes in Market. Microstruct. Liq. 2015, 1, 1550005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizoiu, M.A.; Lee, Y.; Mishra, S.; Xie, L. Hawkes processes for events in social media. In Frontiers of Multimedia Research, 1st ed.; Chang, S., Ed.; Association for Computing Machinery and Morgan & Claypool: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmowski, Z.; Puchalska, D. Modeling social media contagion using Hawkes processes. J. Pol. Math. Soc. 2021, 49, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.H.; Liu, X.; Mohler, G. Hawkes process modeling of COVID-19 with mobility leading indicators and spatial covariates. Int. J. Forecast. 2022, 38, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrechts, P.; Liniger, T.; Lin, L. Multivariate Hawkes processes: An application to financial data. J. Appl. Probab. 2011, 48, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowsher, C.G. Modelling security market events in continuous time: Intensity based, multivariate point process models. J. Econom. 2007, 141, 876–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Liu, A.; Chen, J.; Hawkes, A. Applications of a multivariate Hawkes process to joint modeling of sentiment and market return events. Quant. Finance 2018, 18, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zha, H.; Song, L. Learning Triggering Kernels for Multi-dimensional Hawkes Processes. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2013; Volume 28, pp. 1301–1309. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v28/zhou13.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Luo, D.; Xu, H.; Zhen, Y.; Ning, X.; Zha, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W. Multi-task multi-dimensional Hawkes processes for modeling event sequences. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2015, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015; pp. 3685–3691. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1805/10142 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Embrechts, P.; Kirchner, M. Hawkes graphs. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 2018, 62, 132–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.H.; Barukub, O.M. Graph-Based Text Representation and Matching: A Review of the State of the Art and Future Challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 87562–87583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edited by Segev, E. Semantic Network Analysis in Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Laub, P.J.; Taimre, T.; Pollett, P.; Taimre, T. Hawkes Processes. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1507.02822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, P.J.; Lee, Y.; Pollett, K.P.; Taimre, T. Hawkes Models and Their Applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, A.; Lindgren, S.; Sainudiin, R. Hawkes Processes on Social and Mass Media, International Conference on Data Technologies and Applications 2023. Available online: https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1827189/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Daley, D.J.; Vere-Jones, D. An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume I: Elementary Theory and Methods, 2nd ed.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Blasch, E. Hawkes Process Modeling of Block Arrivals in Bitcoin Blockchain. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.16666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nho, J.H.; Park, S. Research trends in the Korean Journal of Women Health Nursing from 2011 to 2021: A quantitative content analysis. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2023, 29, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisley, T.; Ross, G.; Paulin, D.; Easto, J. Estimation of Multivariate Discrete Hawkes Processes: An Application to Incident Monitoring. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.20085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shojaie, A.; Shea-Brown, E.; Witten, D. The multivariate Hawkes process in high dimensions: Beyond mutual excitation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.04928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, Y.A.; Chapfuwa, P.; Davis, C.; Henao, R. Flexible Triggering Kernels for Hawkes Process Modeling. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 219, 1–17. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v219/isik23a/isik23a.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

| Short Name | Title | Author | Vocabulary Size | Length in Sentences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darwin | On the Origin of Species | Charles Darwin | 5728 | 4036 |

| Einstein | Relativity: The Special and General Theory | Albert Einstein | 2222 | 1107 |

| Faraday | The Chemical History of a Candle | Michael Faraday | 1563 | 2563 |

| Freud | Dream Psychology | Sigmund Freud | 4520 | 1977 |

| Paine | Common Sense | Thomas Paine | 637 | 2558 |

| Plato | The Republic | Plato | 5686 | 5268 |

| Word | Number of Occurrences | (※) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| formation | 134 | 0.446 | 0.143 | 2280.488 |

| hybrid | 124 | 4.971 | 0.199 | 617.345 |

| cross | 160 | 0.534 | 0.171 | 297.335 |

| class | 123 | 0.010 | 0.130 | 220.608 |

| selection | 350 | 0.029 | 0.148 | 91.912 |

| instinct | 100 | 4.744 | 0.261 | 88.223 |

| group | 212 | 0.140 | 0.181 | 41.714 |

| island | 138 | 6.593 | 0.333 | 39.887 |

| period | 267 | 0.010 | 0.146 | 37.960 |

| world | 145 | 0.010 | 0.148 | 31.846 |

| organ | 164 | 1.438 | 0.260 | 27.215 |

| production | 125 | 0.010 | 0.150 | 26.628 |

| plant | 302 | 0.062 | 0.178 | 22.628 |

| structure | 222 | 0.015 | 0.156 | 22.617 |

| habit | 145 | 0.020 | 0.162 | 19.592 |

| variety | 360 | 1.250 | 0.291 | 13.272 |

| part | 253 | 0.013 | 0.165 | 11.025 |

| character | 242 | 0.454 | 0.257 | 9.247 |

| theory | 130 | 0.010 | 0.164 | 8.650 |

| species | 1005 | 0.429 | 0.261 | 8.021 |

| Word | Number of Occurrences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| velocity | 84 | 0.143 | 0.188 | 30.516 |

| field | 78 | 0.832 | 0.275 | 11.681 |

| light | 82 | 0.196 | 0.239 | 6.240 |

| body | 113 | 0.189 | 0.240 | 5.845 |

| equation | 50 | 0.741 | 0.322 | 5.092 |

| motion | 98 | 0.188 | 0.246 | 4.932 |

| position | 53 | 0.173 | 0.245 | 4.751 |

| theory | 142 | 0.688 | 0.337 | 3.958 |

| place | 58 | 0.010 | 0.181 | 2.977 |

| co-ordinate | 86 | 0.152 | 0.264 | 2.646 |

| point | 104 | 0.115 | 0.256 | 2.429 |

| law | 118 | 0.258 | 0.301 | 2.341 |

| line | 52 | 0.010 | 0.186 | 2.298 |

| relativity | 152 | 0.135 | 0.268 | 2.184 |

| reference | 72 | 0.010 | 0.188 | 2.067 |

| principle | 62 | 0.375 | 0.342 | 2.058 |

| time | 98 | 0.065 | 0.249 | 1.601 |

| space | 77 | 0.095 | 0.268 | 1.535 |

| distance | 53 | 0.163 | 0.315 | 1.221 |

| system | 101 | 0.224 | 0.345 | 1.188 |

| Word | Number of Occurrences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| flame | 133 | 0.396 | 0.169 | 247.670 |

| candle | 241 | 0.081 | 0.157 | 115.727 |

| jar | 78 | 0.011 | 0.141 | 62.389 |

| gas | 97 | 0.010 | 0.146 | 37.606 |

| carbon | 85 | 2.335 | 0.269 | 37.103 |

| water | 193 | 2.403 | 0.274 | 34.772 |

| oxygen | 115 | 3.134 | 0.306 | 26.441 |

| heat | 95 | 0.187 | 0.203 | 20.215 |

| acid | 86 | 0.252 | 0.216 | 16.023 |

| atmosphere | 51 | 0.010 | 0.156 | 15.353 |

| hydrogen | 78 | 0.167 | 0.210 | 13.548 |

| air | 207 | 0.221 | 0.223 | 11.207 |

| iron | 59 | 0.242 | 0.292 | 2.556 |

| combustion | 98 | 0.045 | 0.222 | 2.357 |

| experiment | 100 | 0.010 | 0.187 | 2.184 |

| piece | 88 | 0.035 | 0.221 | 1.910 |

| vessel | 51 | 0.145 | 0.285 | 1.716 |

| action | 80 | 0.238 | 0.388 | 0.862 |

| substance | 102 | 0.054 | 0.274 | 0.774 |

| part | 73 | 0.010 | 0.216 | 0.639 |

| Word | Number of Occurrences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychic | 134 | 0.100 | 0.136 | 1081.268 |

| dream | 791 | 0.193 | 0.183 | 52.727 |

| process | 104 | 0.010 | 0.143 | 48.251 |

| content | 110 | 0.010 | 0.146 | 36.565 |

| system | 69 | 0.560 | 0.228 | 24.712 |

| wish | 178 | 0.238 | 0.211 | 18.195 |

| consciousness | 65 | 0.112 | 0.196 | 15.783 |

| thought | 162 | 0.194 | 0.210 | 15.365 |

| work | 69 | 0.010 | 0.160 | 11.299 |

| analysis | 92 | 0.010 | 0.163 | 9.023 |

| sleep | 94 | 0.498 | 0.263 | 8.937 |

| activity | 60 | 0.010 | 0.167 | 6.947 |

| formation | 51 | 0.010 | 0.171 | 5.324 |

| interpretation | 54 | 0.010 | 0.184 | 2.549 |

| life | 83 | 0.010 | 0.185 | 2.419 |

| day | 106 | 0.054 | 0.229 | 2.277 |

| state | 66 | 0.010 | 0.193 | 1.640 |

| child | 73 | 0.185 | 0.303 | 1.634 |

| form | 60 | 0.010 | 0.195 | 1.475 |

| idea | 69 | 0.204 | 0.322 | 1.394 |

| Word | Number of Occurrences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| king | 74 | 0.674 | 0.274 | 9.774 |

| continent | 48 | 0.035 | 0.202 | 3.942 |

| government | 63 | 0.399 | 0.358 | 1.866 |

| britain | 45 | 0.031 | 0.223 | 1.577 |

| england | 50 | 0.140 | 0.323 | 0.944 |

| america | 45 | 0.010 | 0.220 | 0.571 |

| time | 61 | 0.382 | 0.999 | 0.382 |

| power | 45 | 0.033 | 0.327 | 0.209 |

| Word | Number of Occurrences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| justice | 191 | 0.056 | 0.152 | 126.257 |

| god | 124 | 0.031 | 0.151 | 70.764 |

| pleasure | 108 | 0.041 | 0.156 | 64.617 |

| knowledge | 133 | 0.042 | 0.177 | 15.639 |

| soul | 197 | 0.013 | 0.159 | 15.349 |

| opinion | 100 | 0.086 | 0.202 | 9.287 |

| state | 359 | 0.018 | 0.172 | 9.145 |

| art | 113 | 0.091 | 0.221 | 5.013 |

| life | 172 | 0.073 | 0.227 | 3.330 |

| principle | 102 | 0.010 | 0.183 | 2.716 |

| men | 219 | 0.010 | 0.192 | 1.687 |

| nature | 211 | 0.010 | 0.195 | 1.496 |

| city | 110 | 0.010 | 0.196 | 1.410 |

| reason | 119 | 0.011 | 0.201 | 1.241 |

| man | 321 | 0.010 | 0.201 | 1.155 |

| truth | 120 | 0.010 | 0.203 | 1.080 |

| friend | 112 | 0.010 | 0.207 | 0.891 |

| word | 102 | 0.010 | 0.227 | 0.447 |

| question | 112 | 0.010 | 0.232 | 0.384 |

| right | 131 | 0.345 | 0.884 | 0.367 |

| Text | Number of Occurrences | Relaxation Time τ | Shape Parameter β | BIC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Darwin | 0.936 | 0.983 | 0.078 | 0.176 | 0.117 | 0.287 | −0.395 | 0.832 |

| Einstein | 0.821 | 0.885 | 0.237 | 0.670 | 0.212 | 0.329 | 0.419 | 0.437 |

| Faraday | 0.483 | 0.501 | 0.016 | 0.407 | 0.033 | 0.431 | −0.245 | 0.395 |

| Freud | 0.840 | 0.990 | 0.151 | 0.439 | 0.220 | 0.168 | −0.115 | 0.496 |

| Paine | 0.357 | 0.891 | 0.253 | 0.764 | 0.021 | 0.621 | 0.257 | 0.361 |

| Plato | 0.251 | 0.901 | −0.300 | 0.184 | −0.149 | 0.873 | 0.207 | 0.624 |

| Process | Book | Number of Occurrences | BIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| univariate Hawkes | Einstein | 9.37 | 3.15 | 3.69 | 6.56 |

| Darwin | 1.43 | 7.43 | 6.23 | 8.44 | |

| Faraday | 3.10 | 9.47 | 8.91 | 2.97 | |

| Freud | 3.52 | 5.25 | 3.51 | 6.29 | |

| Paine | 3.86 | 5.46 | 9.61 | 5.39 | |

| Plato | 2.85 | 1.99 | 5.30 | 3.81 | |

| multivariate Hawkes | Einstein | 2.12 | 1.22 | 1.57 | 5.41 |

| Darwin | 1.24 | 4.57 | 2.21 | 5.36 | |

| Faraday | 2.43 | 7.51 | 5.81 | 8.49 | |

| Freud | 8.21 | 5.28 | 4.79 | 2.60 | |

| Paine | 3.01 | 5.11 | 1.01 | 3.80 | |

| Plato | 6.10 | 4.38 | 5.17 | 3.29 |

| Darwin | Einstein | Freud | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node | Δai | TF-IDF | Degree Centrality | Node | Δai | TF-IDF | Degree Centrality | Node | Δai | TF-IDF | Degree Centrality |

| species | 1.1250 | 0.02013 | 0.14127 | relativity | 0.8213 | 0.03277 | 0.06735 | dream | 2.0732 | 0.04786 | 0.204243 |

| period | 0.7721 | 0.00393 | 0.03561 | law | 0.7765 | 0.00911 | 0.05204 | life | 0.7262 | 0.00357 | 0.030397 |

| selection | 0.2300 | 0.00726 | 0.04724 | light | 0.7715 | 0.00749 | 0.05230 | form | 0.4541 | 0.00267 | 0.016945 |

| cross | 0.2029 | 0.00407 | 0.00763 | body | 0.6530 | 0.00873 | 0.05689 | analysis | 0.3601 | 0.00556 | 0.028069 |

| plant | 0.1817 | 0.00627 | 0.01453 | system | 0.5132 | 0.00780 | 0.06582 | thought | 0.3168 | 0.00537 | 0.025352 |

| theory | 0.1802 | 0.00270 | 0.02078 | time | 0.4872 | 0.00757 | 0.06505 | process | 0.2235 | 0.00559 | 0.022377 |

| part | 0.1603 | 0.00374 | 0.02609 | point | 0.2187 | 0.00803 | 0.03903 | state | 0.1755 | 0.00288 | 0.022377 |

| class | 0.0453 | 0.00182 | 0.01148 | reference | 0.2175 | 0.00657 | 0.03929 | day | 0.1222 | 0.00456 | 0.03583 |

| habit | −0.0095 | 0.00213 | 0.01148 | place | −0.0674 | 0.00456 | 0.03265 | consciousness | 0.1075 | 0.00780 | 0.022248 |

| world | −0.0652 | 0.00211 | 0.02115 | space | −0.0780 | 0.00595 | 0.05306 | idea | 0.0348 | 0.00292 | 0.015522 |

| structure | −0.0659 | 0.00461 | 0.03357 | motion | −0.2615 | 0.00895 | 0.06429 | sleep | −0.0057 | 0.00556 | 0.03389 |

| character | −0.0694 | 0.00357 | 0.02275 | co-ordinate | −0.3237 | 0.00324 | 0.00536 | wish | −0.0366 | 0.00778 | 0.051093 |

| island | −0.1285 | 0.00270 | 0.01214 | principle | −0.3451 | 0.00471 | 0.03648 | formation | −0.1510 | 0.00308 | 0.012676 |

| group | −0.1385 | 0.00537 | 0.01788 | field | −0.3476 | 0.00712 | 0.04388 | activity | −0.2573 | 0.00437 | 0.020437 |

| variety | −0.1548 | 0.00616 | 0.01403 | line | −0.3938 | 0.00402 | 0.02041 | system | −0.3008 | 0.00297 | 0.018238 |

| instinct | −0.1672 | 0.00240 | 0.01170 | distance | −0.4206 | 0.00417 | 0.03495 | psychic | −0.3025 | 0.01609 | 0.048118 |

| organ | −0.2482 | 0.00322 | 0.01577 | theory | −0.4460 | 0.01541 | 0.07985 | interpretation | −0.3127 | 0.00393 | 0.017074 |

| hybrid | −0.4656 | 0.00503 | 0.00756 | position | −0.4774 | 0.00409 | 0.02934 | content | −0.5062 | 0.00473 | 0.030268 |

| production | −0.5281 | 0.00218 | 0.00545 | velocity | −0.5738 | 0.01345 | 0.05281 | work | −0.7205 | 0.00310 | 0.023412 |

| formation | −0.8565 | 0.00278 | 0.01366 | equation | −0.7238 | 0.01056 | 0.01250 | child | −2.0006 | 0.00371 | 0.021731 |

| Faraday | Paine | Plato | |||||||||

| Node | Δai | TF-IDF | Degree Centrality | Node | Δai | TF-IDF | Degree Centrality | Node | Δai | TF-IDF | Degree Centrality |

| substance | 0.5210 | 0.00919 | 0.04986 | time | 0.6041 | 0.00736 | 0.04880 | man | 0.4548 | 0.00692 | 0.07140 |

| combustion | 0.4490 | 0.01754 | 0.05252 | continent | 0.2181 | 0.01216 | 0.03944 | state | 0.4078 | 0.00779 | 0.06930 |

| experiment | 0.3492 | 0.00901 | 0.04410 | government | 0.1954 | 0.01069 | 0.04425 | truth | 0.2285 | 0.00263 | 0.02842 |

| 2action | 0.3126 | 0.00607 | 0.04454 | england | 0.0994 | 0.01022 | 0.03944 | word | 0.1753 | 0.00221 | 0.01009 |

| air | 0.3018 | 0.01569 | 0.12076 | britain | 0.0010 | 0.00920 | 0.03110 | nature | 0.1652 | 0.00453 | 0.04351 |

| piece | 0.2421 | 0.00564 | 0.04675 | king | −0.2363 | 0.01255 | 0.04703 | opinion | 0.0921 | 0.00257 | 0.01930 |

| part | 0.1817 | 0.00468 | 0.03989 | power | −0.3051 | 0.00543 | 0.03843 | right | 0.0841 | 0.00284 | 0.02632 |

| water | 0.1041 | 0.01463 | 0.11700 | america | −0.5766 | 0.01140 | 0.03540 | men | 0.0721 | 0.00562 | 0.04877 |

| candle | 0.0081 | 0.02617 | 0.10193 | justice | 0.0658 | 0.00870 | 0.03895 | ||||

| carbon | −0.0058 | 0.01522 | 0.04675 | pleasure | 0.0433 | 0.00323 | 0.01579 | ||||

| gas | −0.0113 | 0.01305 | 0.05894 | art | 0.0269 | 0.00285 | 0.02105 | ||||

| vessel | −0.0677 | 0.00686 | 0.03302 | knowledge | −0.0127 | 0.00289 | 0.03105 | ||||

| atmosphere | −0.0687 | 0.00554 | 0.03412 | city | −0.0275 | 0.00404 | 0.02605 | ||||

| jar | −0.0965 | 0.01050 | 0.04387 | question | −0.0759 | 0.00243 | 0.02018 | ||||

| oxygen | −0.1220 | 0.02059 | 0.06160 | reason | −0.0761 | 0.00258 | 0.02597 | ||||

| flame | −0.1878 | 0.01444 | 0.07755 | friend | −0.1050 | 0.00239 | 0.01746 | ||||

| hydrogen | −0.2463 | 0.01396 | 0.04188 | principle | −0.1391 | 0.00221 | 0.01947 | ||||

| iron | −0.4329 | 0.00532 | 0.04033 | soul | −0.2651 | 0.00595 | 0.04825 | ||||

| heat | −0.5906 | 0.00856 | 0.05096 | god | −0.3241 | 0.00378 | 0.01263 | ||||

| acid | −0.6399 | 0.01540 | 0.04742 | life | −0.7905 | 0.00371 | 0.03886 | ||||

| Text | Δai and TF-IDF | Δai and Degree Centrality |

|---|---|---|

| Darwin | 0.64292 | 0.73385 |

| Einstein | 0.32818 | 0.48593 |

| Faraday | −0.04482 | 0.16863 |

| Freud | 0.62809 | 0.64965 |

| Paine | −0.15629 | 0.48761 |

| Plato | 0.29113 | 0.34874 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogura, H.; Hanada, Y.; Osakabe, K.; Kondo, M. Modeling the Mutual Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts Using Multivariate Hawkes Processes. J 2025, 8, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040040

Ogura H, Hanada Y, Osakabe K, Kondo M. Modeling the Mutual Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts Using Multivariate Hawkes Processes. J. 2025; 8(4):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgura, Hiroshi, Yasutaka Hanada, Keitaro Osakabe, and Masato Kondo. 2025. "Modeling the Mutual Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts Using Multivariate Hawkes Processes" J 8, no. 4: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040040

APA StyleOgura, H., Hanada, Y., Osakabe, K., & Kondo, M. (2025). Modeling the Mutual Dynamic Correlations of Words in Written Texts Using Multivariate Hawkes Processes. J, 8(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/j8040040