Law, Socio-Legal Governance, the Internet of Things, and Industry 4.0: A Middle-Out/Inside-Out Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Changing Regulatory Framework

2.1. Web 4.0, Industry 4.0, and IoT

2.2. New Regulatory Challenges

A digital twin of a citizen is a digital representation of an individual. […]. Governments are developing digital twins of citizens to monitor the environment citizens live in and address health, safety, travel, and social media impacts on society. The spectrum of complexity of the models and tools can help governments make better decisions for monitoring and supporting patients, prisoners, passengers, or the elderly. Some governments, such as China’s, are building a scoring methodology. Aggregated citizen twins can help map broad patterns and drive resource allocation. […] By implementing MRL (Machine-Readable Legislation), the room for interpretation of legislative or executive intent is eliminated from the process, instead making the law that is passed the same as that which is implemented.[30]

2.3. The Emergence of LawTech Web Services

2.4. Socio-Legal Ecosystems

The Social Web is an ecosystem of participation, where value is created by the aggregation of many individual user contributions. The Semantic Web is an ecosystem of data, where value is created by the integration of structured data from many sources.[61]

To create an open data ecosystem at least four key elements should be captured: (1) releasing and publishing open data on the internet; (2) searching, finding, evaluating and viewing data and their related licenses; (3) cleansing, analyzing, enriching, combining, linking, and visualizing data; and (4) interpreting and discussing data and providing feedback to the data provider and other stakeholders. Furthermore, to integrate the ecosystem elements and to let them act as an integrated whole, there should be three additional elements: (5) user pathways showing directions for how open data can be used, (6) a quality management system, and (7) different types of metadata to be able to connect the elements.[76] (p. 17)

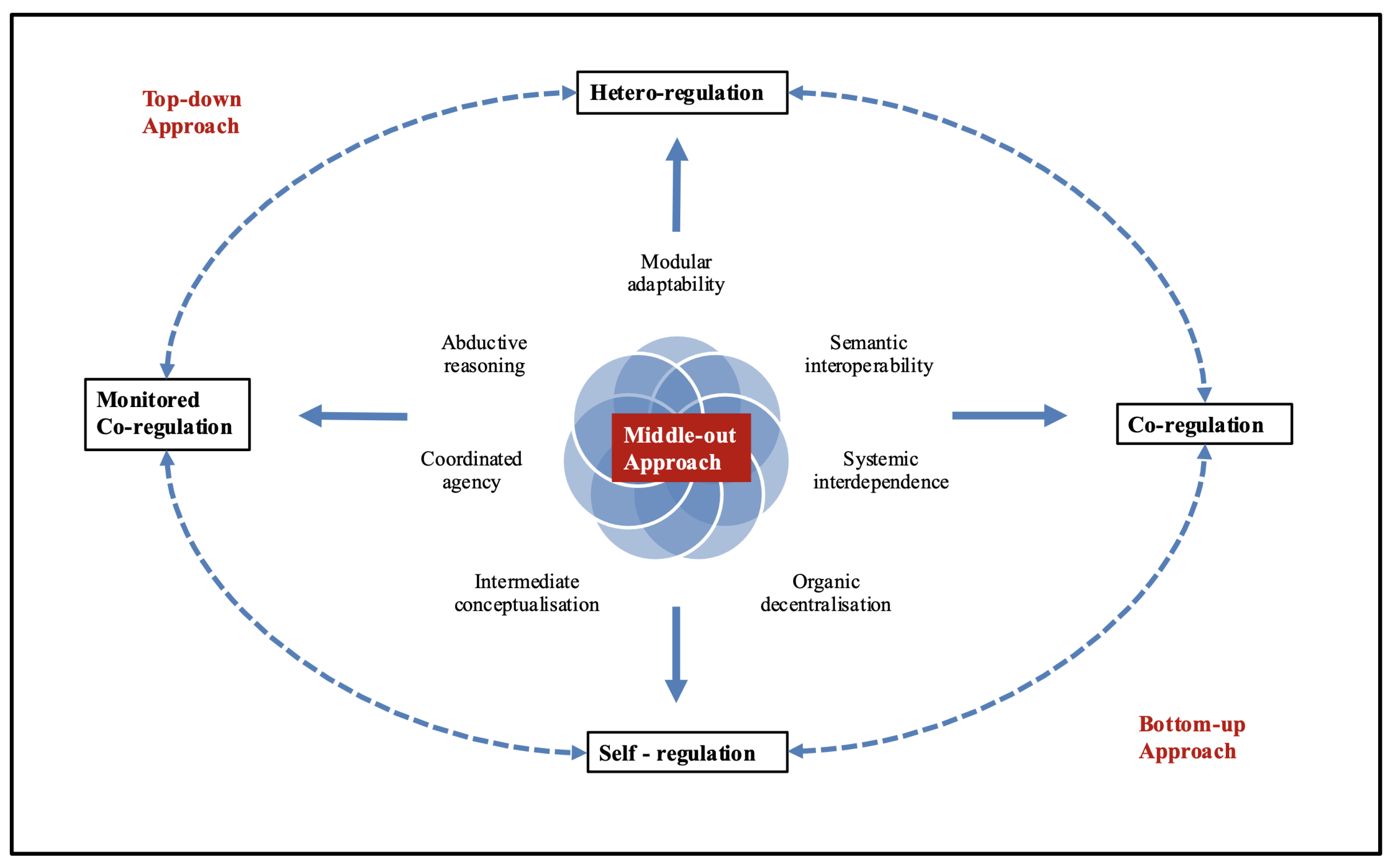

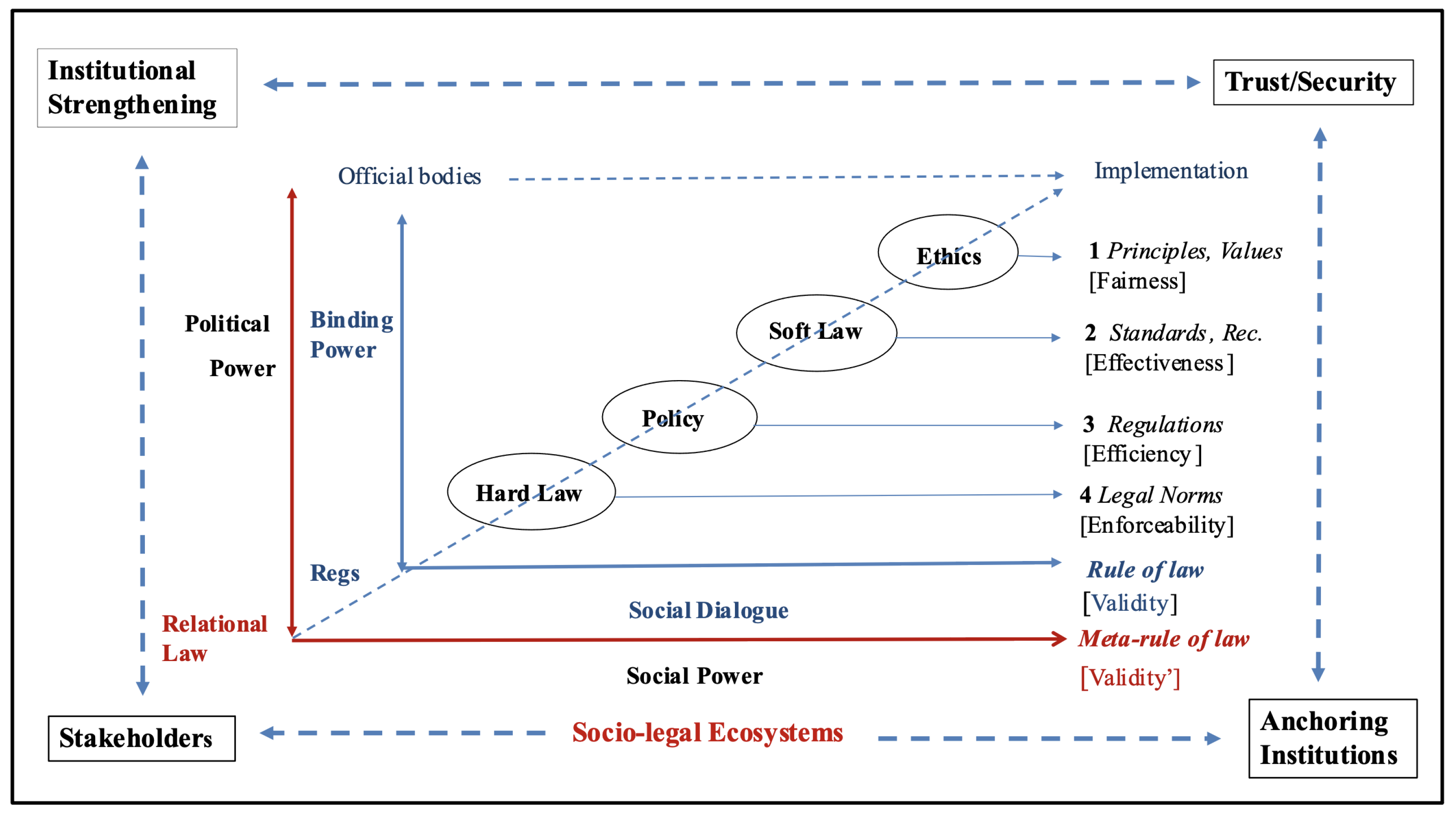

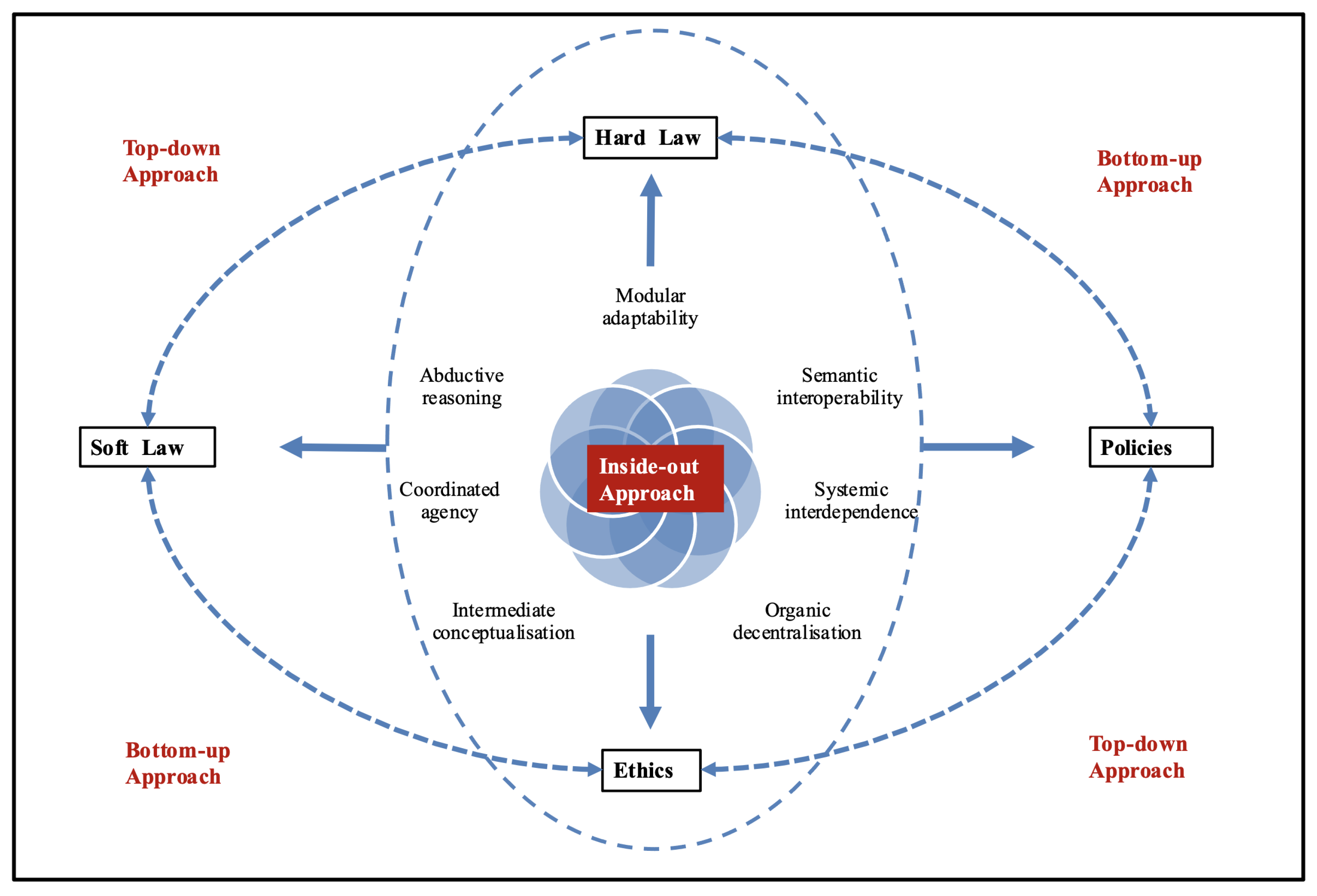

3. Socio-Legal Governance

3.1. Legal Governance and the Limits of Legal Instruments

3.2. Phenomenology and Political History

while 19th century formal legal rationality was largely bracketed and superseded by the substantive rationality of the 20th-century regulatory state, both are now being challenged by the rise of a new legal rationality, namely, negotiated process rationality and the attraction it holds for the interests of corporate and transnational governance.[ibid., p. 327]

3.3. Rule and Metarule of Law

3.4. Scheme of the Metarule of law

3.5. Socio-Legal Governance for Hybrid Intelligence

What are the appropriate models for negotiation, agreements, planning, and delegation in hybrid teams? What is the best way to verify the agent’s architecture and behaviour to prove their ethical “scope” (ethics in design)? What is the best way to measure ethical, legal, and societal (ELS) performance and compare designed versus learning systems (ethics in design)? Which methodology can ensure ELS alignment during the design, development, and use of ELS-aware HI systems (ethics by design)? How can explanations be personalized so that they align with the users’ needs and capabilities? How can the quality and strength of the explanations be evaluated?

OIs contain policies that facilitate the governance of participant activity, either through what a participant is allowed to do in certain circumstances or what a participant may choose (not) to do for the sake of any social consequences. Online institutions embody both affordances and norms. […] the sociotechnical systems complement of object-oriented programming’s Model-View-Controller (MVC), where the world (W) is a collection of social spaces, that are sub-contexts of the real world, institutions (I) are the policy frameworks into which the values that characterise the system are imbued, and the technological space (T) where online inter-actions are processed according to software representations of the institutional conventions.[134] (pp. 2–4)

3.6. Legal Compliance: Compliance through Design

3.7. Beyond the AI4People SMART Model for Legal Governance

3.8. Driving and Enabling Systems

Technology is now starting to disrupt the law. These changes are not being driven primarily by lawyers, bar associations, judges, or court administrators. They are being pushed most significantly by the disputants and litigants themselves. Because citizens utilize technology in almost every area of their lives, they now expect that when they encounter a dispute or file a lawsuit they will have access to similar kinds of tools to help them manage that process.[59]

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casanovas, P.; González-Conejero, J.; de Koker, L. Legal Compliance by Design (LCbD) and through Design (LCtD): Preliminary Survey. TERECOM@Jurix 2017. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Technologies for Regulatory Compliance, Luxembourg, 13 December 2017; Volume 2049, pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas, P.; Rodríguez-Doncel, V.; González-Conejero, J. The role of pragmatics in the web of data. In Pragmatics and Law; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 293–330. [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas, P.; Mendelson, D.; Poblet, M. A linked democracy approach for regulating public health data. Health Technol. 2017, 7, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanovas, P.; Koker, L.D.; Mendelson, D.; Watts, D. Regulation of Big Data: Perspectives on strategy, policy, law and privacy. Health Technol. 2017, 7, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M.; Governatori, G.; Lam, H.P.; Wynn, M.T. Are we done with business process compliance: State of the art and challenges ahead. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2018, 57, 79–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashmi, M.; Casanovas, P.; de Koker, L. Legal Compliance Through Design: Preliminary Results of a Literature Survey. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Technologies for Regulatory Compliance, Groningen, The Netherlands, 12 December 2018; Volume 2309, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- de Koker, L.; Morris, N.; Jaffer, S. Regulating Financial Services in an Era of Technological Disruption. Law Context.-Socio-Leg. J. 2020, 36, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblet, M.; Casanovas, P.; Rodríguez-Doncel, V. Linked Democracy: Foundations, Tools, and Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; OA Law Brief 750. [Google Scholar]

- Governatori, G.; Casanovas, P.; de Koker, L. On the Formal Representation of the Australian Spent Conviction Scheme. In Rules and Reasoning; Gutiérrez-Basulto, V., Kliegr, T., Soylu, A., Giese, M., Roman, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Doncel, V.; Santos, C.; Casanovas, P.; Gomez-Perez, A. Legal aspects of linked data–The European framework. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2016, 32, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Doncel, V.; Casanovas, P.; Araszkiewicz, M.; Palmirani, M.; Pagallo, U.; Sartor, V.A. Explainable AI in Law, Law as Web of Data, Privacy, and the Rule of Law; AICOL (2021). AI Approaches to the Complexity of Legal Systems. AICOL International Workshops 2018–2020: AICOL-XI@JURIX 2018, AICOL-XII@JURIX 2019, AICOL-XIII@JURIX 2020, XAILA@JURIX 2020. Revised Selected Papers on Explainable AI in Law, Law as Web of Data, Privacy, and the Rule of Law. LNAI, 13048; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pagallo, U.; Aurucci, P.; Casanovas, P.; Chatila, R.; Chazerand, P.; Dignum, V.; Luetge, C.; Madelin, R.; Schafer, B.; Peggy, V. On Good AI Governance: 14 Priority Actions, a SMART Model of Governance, and a Regulatory Toolbox. In AI4PEOLE; Atomium Technical Report; Atomium Technical: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3486508 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Aghaei, S.; Nematbakhsh, M.A.; Farsani, H.K. Evolution of the World Wide Web: From Web 1.0 to Web 4.0. Int. J. Web Semant. Technol. (IJWesT) 2012, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendler, J.A.; Berners-Lee, T. From the Semantic Web to social machines: A research challenge for AI on the World Wide Web. Artif. Intell. 2010, 174, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, B. Discovering the Future of the Web. J. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2015, 23, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztemel, E.; Gursev, S. Literature review of Industry 4.0 and related technologies. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 127–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Industry 4.0: A survey on technologies, applications and open research issues. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2017, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drath, R.; Horch, A. Industrie 4.0: Hit or hype? [industry forum]. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2014, 8, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.L. Concept and dimensions of web 4.0. Int. J. Comput. Technol. 2017, 16, 7040–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H.A. A cyber-physical systems architecture for industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Manuf. Lett. 2015, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papcun, P.; Kajáti, E.; Koziorek, J. Human Machine Interface in Concept of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Symposium on Digital Intelligence for Systems and Machines (DISA), Košice, Slovakia, 23–25 August 2018; pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, M.; Pentek, T.; Otto, B. Design principles for industrie 4.0 scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 3928–3937. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, E.; Rüsch, M. Industry 4.0 and the current status as well as future prospects on logistics. Comput. Ind. 2017, 89, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbarkar, A.; Serafin, N.; Betti, F. How fourth industrial revolution tech helped companies survive the COVID crisis. In Proceedings of the World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland, 4 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, R.; Blanton, C.; Mendonsa, A.; Cannon, N.; Finnerty, B.; Lacheca, D.; Mickoleit, A.; Thielemann, K. Technology Trends in Government, 2019–2020; Gartner Report, Technical Report ID G00389782; Gartner: Gold Coast, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mickoleit, A. 7 Ways to Maximize the Impact of Open Government Data: Lessons From France; Gartner Report, Technical Report ID G00716846; Gartner: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, M. Research Note. Rules as Code. Law Context 2020, 37, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough, T.; Fraser, H.; Barnes, C. Legislation as Code for New Zealand: Opportunities, Risks, and Recommendations. 2021. Available online: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/journals/NZLFRRp/2021/3.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Mendonsa, A. Hype Cycle for Digital Government Technology, 2021; Techreport—ID G00747518; Gartner: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Breuker, J. Law, Ontologies and the Semantic Web: Channelling the Legal Information Flood; IOS Press: Brentwood, TN, USA, 15 January 2009; Volume 188. [Google Scholar]

- Athan, T.; Boley, H.; Governatori, G.; Palmirani, M.; Paschke, A.; Wyner, A. Oasis legalruleml. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (ICAIL ’13), Rome, Italy, 10–14 June 2013; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas, P.; Rodríguez-Doncel, V.; Santos, C.; Gómez-Pérez, A. A European Framework for Regulating Data and Metadata Markets. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Society, Privacy and the Semantic Web—Policy and Technology (PrivOn2016) Co-Located with 15th International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC), Kobe, Japan, 18 October 2016; Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1750/paper-04.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Palmirani, M. Hybrid Model for Law in the Digital Era: A Dialogic Model through Text and Code. In Proceedings of the 3rd COHUBICOL Philosopher’s Seminar on “Code-Driven Law”, Organized Online, Brussels, Belgium, 9 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- d’Aquin, M.; Davies, J.; Motta, E. Smart Cities’ Data: Challenges and Opportunities for Semantic Technologies. IEEE Internet Comput. 2015, 19, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Aquin, M.; Motta, E.; Sabou, M.; Angeletou, S.; Gridinoc, L.; Lopez, V.; Guidi, D. Toward a New Generation of Semantic Web Applications. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2008, 23, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, E. On the future of legal publishing services in the Semantic Web. Future Internet 2018, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehm, G.; Galanis, D.; Labropoulou, P.; Piperidis, S.; Welß, M.; Usbeck, R.; Köhler, J.; Deligiannis, M.; Gkirtzou, K.; Fischer, J.; et al. Towards an Interoperable Ecosystem of AI and LT Platforms: A Roadmap for the Implementation of Different Levels of Interoperability. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Language Technology Platforms (IWLTP’20) European Language Resources Association, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fensel, D.; Şimşek, U.; Angele, K.; Huaman, E.; Kärle, E.; Panasiuk, O.; Toma, I.; Umbrich, J.; Wahler, A. Knowledge Graphs: Methodology, Tools and Selected Use Cases; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kirrane, S.; Sabou, M.; Fernández, J.D.; Osborne, F.; Robin, C.; Buitelaar, P.; Motta, E.; Polleres, A. A Decade of Semantic Web Research through the Lenses of a Mixed Methods Approach. Semant. Web 2020, 11, 979–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Law Society. Lawtech: A Comparative Analysis of Legal Technology in the UK and in Other Jurisdictions, London. 2019. Available online: https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/en/topics/research/lawtech-comparative-analysis-of-legal-technology (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Rakshit, U.; Koh, T.Y.; Xiaohan, C. Legal Technology in Singapore, 2nd ed.; LawTech. Asia: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M.; Übergang, J. Artificial Intelligence in Law: An Overview. Precedent (Sydney NSW) 2017, 139, 35–38. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20172037 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Blijd, R. DoA: Data on How Many Legal Tech Companies Rise & Die. 2019. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/bdcwsdnn/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Blijd, R. The Fall of Legal Tech and How to Pivot Out. 2020. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4mpbke6u (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Blijd, R. Rebound: 10 Growth Areas in Our New Perimeter Prosperity. 2020. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yckps7nj (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- ILTA. International Legal Technology Association Survey. Executive Summary; International Legal Technology Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ILTA. International Legal Technology Association Survey. Executive Summary; International Legal Technology Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ILTA. Survey on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. December 2019. Available online: http://epubs.iltanet.org/i/1193169-aiml19/0?_ga=2.81313303.1093332486.1578860678-709782971.1578860678 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- ILTA. International Legal Technology Association Survey. Executive Summary; International Legal Technology Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ILTA. International Legal Technology Association Survey. Executive Summary; International Legal Technology Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Soh, J.T.H. The State of Legal Innovation in Asia-Pacific; Research Collection School of Law, Singapore Management University: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- Blijd, R. How Big is the Addressable Market for the Legal Industry? 2021. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2snj7f4v (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- INTAPP. Form S-1 Registration Statement under the Securities Act of 1933; Filed on Securities and Exchange Commission: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021.

- Tung, K. AI, the internet of legal things, and lawyers. J. Manag. Anal. 2019, 6, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, M. AI is Going to Change the 80/20 Rule. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2017. Available online: https://hbr.org/2017/02/ai-is-going-to-change-the-8020-rule (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Ashley, K.D. Artificial Intelligence and Legal Analytics: New Tools for Law Practice in the Digital Age; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, L.T. Research Handbook on the Law of Artificial Intelligence; Chapter Finding the Right Balance in Artificial Intelligence and Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northhampton, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rule, C. Online Dispute Resolution and the Future of Justice. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2020, 16, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsh, M.E.; Rabinovich, O. Digital Justice: Technology and the Internet of Disputes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, T. Collective knowledge systems: Where the Social Web meets the Semantic Web. J. Web Semant. 2008, 6, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhelis, O.; Luoma, E.; Warma, H. Defining an internet-of-things ecosystem. In InInternet of Things, Smart Spaces, and Next Generation Networking; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Millard, C.; Hon, W.K.; Singh, J. Internet of Things Ecosystems: Unpacking Legal Relationships and Liabilities. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering (IC2E’17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4–7 April 2017; pp. 286–291. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Schneider, J.; Rehm, G.; Montiel-Ponsoda, E.; Rodriguez-Doncel, V.; Revenko, A.; Karampatakis, S.; Khvalchik, M.; Sageder, C.; Gracia, J.; Maganza, F. Orchestrating NLP Services for the Legal Domain. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LRCE), Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber, W. Data sharing in IoT ecosystems and competition law: The example of connected cars. J. Compet. Law Econ. 2019, 15, 381–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagallo, U. The Laws of Robots: Crimes, Contracts, and Torts; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi, E.; Bloise, N.; Dirutigliano, J.; Fici, G.P.; Pagallo, U.; Primatesta, S.; Quagliotti, F. The Design of GDPR-Abiding Drones Through Flight Operation Maps: A Win–Win Approach to Data Protection, Aerospace Engineering, and Risk Management. Minds Mach. 2019, 29, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, E. Urban Unmanned Aerial Systems Operations. Law Context 2019, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.T.; de Castro Neto, M.; Aparicio, M. The impacts of open data initiatives on smart cities: A framework for evaluation and monitoring. Cities 2020, 106, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Seligman, L.; Rosenthal, A.; Kurcz, C.; Greer, M.; Macheret, C.; Sexton, M.; Eckstein, A. “Big Metadata” The Need for Principled Metadata Management in Big Data Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Data analytics in the Cloud, Snowbird, UT, USA, 22–27 June 2014; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, E.; Sheth, A. Next-generation smart environments: From system of systems to data ecosystems. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2018, 33, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T. Open Data: Infrastructures and ecosystems. Open Data Res. 2011, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reggi, L.; Dawes, S. Open Government Data Ecosystems: Linking Transparency for Innovation with Transparency for Participation and Accountability. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective (EGOV), Guimarães, Portugal, 5–8 September 2016; Volume LNCS-9820, Electronic Government, Part 2: Open Government; Scholl, H.J., Glassey, O., Janssen, M., Klievink, B., Lindgren, I., Parycek, P., Tambouris, E., Wimmer, M.A., Janowski, T., Soares, D.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Porto, Portugal, 2016; pp. 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Styrin, E.; Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Harrison, T.M. Open data ecosystems: An international comparison. Transform. Gov. People Process. Policy 2017, 11, 132–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafabadi, M.M.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Open Government Data Ecosystems: A Closed-Loop Perspective. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-50), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Janssen, M.; Davis, C. Innovation with Open Data: Essential Elements of Open Data Ecosystems. Inform Polity 2014, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leminen, S.; Rajahonka, M.; Westerlund, M.; Wendelin, R. The future of the Internet of Things: Toward heterarchical ecosystems and service business models. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Gill, A.; Hussain, F.K. A Conceptual Framework for Data Governance in IoT-enabled Digital IS Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Data Science, Prague, Czec Republich, 26–28 July 2019; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Zdravković, M.; Zdravković, J.; Aubry, A.; Moalla, N.; Guedria, W.; Sarraipa, J. Domain framework for implementation of open IoT ecosystems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2552–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Millard, C.; Reed, C.; Cobbe, J.; Crowcroft, J. Accountability in the IoT: Systems, Law, and Ways Forward. Computer 2018, 51, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Pasquier, T.; Bacon, J.; Powles, J.; Diaconu, R.; Eyers, D. Big Ideas Paper: Policy-Driven Middleware for a Legally-Compliant Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 17th International Middleware Conference (Middleware’16), Trento, Italy, 12–16 December 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, S.; Governatori, G.; Namiri, K. Modeling Control Objectives for Business Process Compliance. In Business Process Management; Alonso, G., Dadam, P., Rosemann, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Governatori, G. The Regorous Approach to Process Compliance. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 19th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop, Adelaide, Australia, 21–25 September 2015; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, M.; Governatori, G.; Wynn, M.T. Normative requirements for regulatory compliance: An abstract formal framework. Inf. Syst. Front. 2016, 18, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwabe, D.; Laufer, C.; Casanovas, P. Knowledge Graphs: Trust, Privacy, and Transparency from a Legal Governance Approach. Law Context 2020, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.; Xu, X.; Riveret, R.; Governatori, G.; Ponomarev, A.; Mendling, J. Untrusted Business Process Monitoring and Execution Using Blockchain. In Business Process Management; La Rosa, M., Loos, P., Pastor, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Mendling, J.; Weber, I.; Aalst, W.V.D.; Brocke, J.V.; Cabanillas, C.; Daniel, F.; Debois, S.; Ciccio, C.D.; Dumas, M.; Dustdar, S.; et al. Blockchains for Business Process Management—Challenges and Opportunities. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, H.P.; Hashmi, M.; Kumar, A. Towards a Formal Framework for Partial Compliance of Business Processes. In AI Approaches to the Complexity of Legal Systems XI–XII; Rodríguez-Doncel, V., Palmirani, M., Araszkiewicz, M., Casanovas, P., Pagallo, U., Sartor, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Trubek, D.M.; Santos, A. The New Law and Economic Development: A Critical Appraisal; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Trubek, D.M. Law and development: Forty years after ‘Scholars in Self-Estrangement’. Univ. Tor. Law J. 2016, 66, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistor, K.; Xu, C. Governing emerging stock markets: Legal vs administrative governance.Corporate Governance: An International Review. Corp. Governance Int. Rev. 2005, 13, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. The economic consequences of legal origins. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 285–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaels, R. Comparative Law by Numbers? Legal Origins Thesis, Doing Business Reports, and the Silence of Traditional Comparative Law. Am. J. Comp. Law 2009, 57, 765–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hildebrandt, M. Algorithmic regulation and the rule of law. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2018, 376, 20170355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szabo, N. Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks. First Monday 1997, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippi, P.; Mannan, M.; Reijers, W. Blockchain as a confidence machine: The problem of trust & challenges of governance. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101284. [Google Scholar]

- De Filippi, P. Blockchain Technology as an Instrument for Global Governance; Digital, Governance and Sovereignty Chair; Sciences Po’s: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- De Filippi, P. Blockchain and the Law; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, M. Blockchain and the General Data Protection Regulation; Can distributed ledgers be squared with European data protection law? EPRS—European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Governatori, G.; Idelberger, F.; Milosevic, Z.; Riveret, R.; Sartor, G.; Xu, X. On legal contracts, imperative and declarative smart contracts, and blockchain systems. Artif. Intell. Law 2018, 26, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konashevych, O.; Poblet, M. Is blockchain hashing an effective method for electronic governance? arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.08783. [Google Scholar]

- Konashevych, O.; Poblet, M. April. Blockchain anchoring of public registries: Options and challenges. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 3–5 April 2019; pp. 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Heydebrand, W. Process Rationality as Legal Governance: A Comparative Perspective. Int. Sociol. 2003, 18, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanaha, B.Z. On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Simbirski, B. Cybernetic muse: Hannah Arendt on automation, 1951–1958. J. Hist. Ideas 2016, 77, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkin, H. The Concept of Representation; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Between Facts and Norms; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Territory, Authority, Rights; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scheuerman, W.E. Economic Globalization and the Rule of Law 1. In Constitutionalism and Democracy; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanaha, B.Z. The Tension Between Legal Instrumentalism And The Rule of Law. Syracuse J. Int. Law Commer. 2005, 33, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Omari, L.A.; Barnes, P.; Pitman, G. Optimising COBIT 5 for IT governance: Examples from the public sector. In Proceedings of the ATISR 2012: 2nd International Conference on Applied and Theoretical Information Systems Research, Taipei, Taiwan, 27–29 December 2012; Academy of Taiwan Information Systems Research (ATISR): Taipei, Taiwan, 2012; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann, M. Combining ITIL, COBIT andISO/IEC 27002 for structuringcomprehensive informationtechnology for management inorganizations. Navus Rev. GestãO Tecnol. 2012, 2, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, G. Using IT governance and COBIT to deliver value with IT and respond to legal, regulatory and compliance challenges. Inf. Secur. Tech. Rep. 2006, 11, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalaraj, G.; Singh, A.; Taneja, A. IT Governance Frameworks and COBIT—A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Twentieth Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), Savannah, GA, USA, 7–9 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsaei, A.; Amyot, D.; Pourshahid, A. A Systematic Review of Compliance Measurement Based on Goals and Indicators. In Proceedings of the Advanced Information Systems Engineering Workshops, London, UK, 20–24 June 2011; Salinesi, C., Pastor, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; 2011; pp. 228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, K. Regulation by blockchain: The emerging battle for supremacy between the code of law and code as law. Mod. Law Rev. 2019, 82, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J. A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2019, 1. Available online: https://hdsr.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/l0jsh9d1 (accessed on 14 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J.; Drahos, P. Global Business Regulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Black, J. Decentring regulation: Understanding the role of regulation and self-regulation in a ‘post-regulatory’ world. Curr. Leg. Probl. 2001, 54, 103–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonet, P.; Selznick, P. Law and Society in Transition: Toward Responsive Law; Octagon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Drahos, P. Regulatory Theory: Foundations and Applications; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pohle, J.; Thiel, T. Digital sovereignty, Internet PolicyReview. Alexander Von Humboldt Inst. Internet Soc. Berl. 2020, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L. The Fight for Digital Sovereignty: What It Is, and Why It Matters, Especially for the EU. Philos. Technol. 2020, 33, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. Postscript to Faktizität und Geltung. Philos. Soc. Crit. 1994, 20, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Sustainable Social-Ecological Systems: An Impossiblity? In Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, “Science and Technology for Sustainable Well-Being”, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–19 February 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tuori, K. Critical Legal Positivism; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas, P. Conceptulasation of Rights and Meta-Rule of Law for the Web of Data. Rev. Democr. Gov. Electron. 2015, 1, 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, M.; Kirrane, S.; Padget, J.; Satoh, K. ODRL Policy Modelling and Compliance Checking. In Rules and Reasoning; Fodor, P., Montali, M., Calvanese, D., Roman, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bonatti, P.A.; Kirrane, S.; Petrova, I.M.; Sauro, L. Machine Understandable Policies and GDPR Compliance Checking. KI-Künstliche Intell. 2020, 34, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Binsbergen, L.T.; Liu, L.C.; van Doesburg, R.; van Engers, T. eFLINT: A Domain-Specific Language for Executable Norm Specifications; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; GPCE 2020; pp. 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Akata, Z.; Balliet, D.; de Rijke, M.; Dignum, F.; Dignum, V.; Eiben, G.; Fokkens, A.; Grossi, D.; Hindriks, K.; Hoos, H.; et al. A Research Agenda for Hybrid Intelligence: Augmenting Human Intellect With Collaborative, Adaptive, Responsible, and Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Computer 2020, 53, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.; Dryzek, J.; Ober, J. Algorithmic reflexive governance for socio-techno-ecological systems. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2020, 39, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, P.; Verhagen, H.; Padget, J.; d’Inverno, M. Ethical Online AI Systems through Conscientious Design. IEEE Internet Comput. 2021, 25, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, P.; Casanovas, P. Mirando Hacia El Futuro. Cambios SociohistóRicos Vinculados a la Virtualización; Chapter “La Gobernanza de los Sistemas Artificiales Inteligentes” [The Governance of Artificial Intelligent Systems]; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) [Ministerio de la Presidencia]: Madrid, Spain, 2022. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Barbulescu, M.; Hagiu, A. Leveraging The Scalability: A Distributed Cloud for Tomorrow’s Internet of Autonomous Things. Sci.-Bull.-Econ. Sci. 2020, 19, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou, A.; Dignum, V. Towards ethical and socio-legal governance in AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derave, T.; Prince Sales, T.; Gailly, F.; Poels, G. Comparing Digital Platform Types in the Platform Economy. In Advanced Information Systems Engineering; La Rosa, M., Sadiq, S., Teniente, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi, R.; Li, F.L.; Borgidac, A.; Guizzardia, G.; Horkoff, J.; Mylopoulos, J. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; Chapter An Ontological Interpretation of Non-Functional Requirements; IOS Press: Brentwood, TN, USA, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 344–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanavati, S.; Amyot, D.; Rifaut, A. Legal Goal-Oriented Requirement Language (Legal GRL) for Modeling Regulations. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Modeling in Software Engineering, Hyderabad, India, 2–3 June 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014. MiSE 2014. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, C.; Muthuri, R.; Santos, C. Using Ontologies to Model Data Protection Requirements in Workflows. In Proceedings of the JSAI International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, Kanagawa, Japan, 16–18 November 2015; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Sartoli, S.; Ghanavati, S.; Siami Namin, A. Compliance Requirements Checking in Variable Environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 44th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Virtual Event, 13–17 July 2020; pp. 1093–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Amantea, I.A.; Robaldo, L.; Sulis, E.; Governatori, G.B.G. Semi-automated checking for regulatory compliance in e-Health. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 25th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop (EDOCW), Gold Coast, Australia, 25–29 October 2021; pp. 318–325. [Google Scholar]

- González-Conejero, J.; Teodoro, E.; Casanovas, P. Lynx D1.1 Functional Requirements Analysis Report. 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1256836 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Casanovas, P.; Hashmi, M.; de Koker, L. A Three Steps Methodological Approach for Legal Governance Validation; AICOL@JURIX 2021; Mykolas Romeris University: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boella, G.; Tosatto, S.C.; Ghanavati, S.; Hulstijn, J.; Humphreys, L.; Muthuri, R.; Rifaut, A.; van der Torre, L. Integrating Legal-Urn and Eunomos: Towards a Comprehensive Compliance Management Solution. In International Workshop on AI Approaches to the Complexity of Legal Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Palmirani, M.; Martoni, M. Legal Ontology for Modelling GDPR Concepts and Norms. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, Volume 313: Legal Knowledge and Information Systems; IOS Press: Brentwood, TN, USA, 2018; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, C.; Giurgiu, A. Towards Legal Compliance by Correlating Standards and Laws with a Semi-automated Methodology. In Proceedings of the Benelux Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 10–11 November 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Prakken, H.; Sartor, G. Law and logic: A review from an argumentation perspective. Artif. Intell. 2015, 227, 214–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, M.; Briot, J.P.; de Almeida, V.P.; dos Reis, R.; Silva e Silva, F. Stream-Based Reasoning for IoT Applications—Proposal of Architecture and Analysis of Challenges. Int. J. Semant. Comput. 2017, 11, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reis, R.D.; Endler, M.; de Almeida, V.P.; Haeusler, E.H. A Soft Real-Time Stream Reasoning Service for the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC), Newport Beach, CA, USA, 30 January–1 February 2019; pp. 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, F.; Puschmann, D.; Barnaghi, P.; Carrez, F. A practical evaluation of information processing and abstraction techniques for the internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2015, 2, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maarala, A.I.; Su, X.; Riekki, J. Semantic reasoning for context-aware Internet of Things applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 4, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shreyas, J.; Jumnal, A.; Kumar, S.D.; Venugopal, K.R. Application of computational intelligence techniques for internet of things: An extensive survey. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Stud. 2020, 9, 234–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, R.S.; Jia, X.; Lee, J.; Sun, K.; Colombo, A.W.; Barata, J. Industrial Artificial Intelligence in Industry 4.0—Systematic Review, Challenges and Outlook. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 220121–220139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagallo, U.; Casanovas, P.; Madelin, R. The middle-out approach: Assessing models of legal governance in data protection, artificial intelligence, and the Web of Data. Theory Pract. Legis. 2019, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkin, H. Representation and democracy: Uneasy alliance. Scand. Political Stud. 2004, 27, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboler, A.; Casanovas, P. The Web of Data’s Role in Legal Ecosystems to Address Violent Extremism Fuelled by Hate Speech in Social Media. In AI Approaches to the Complexity of Legal Systems XI–XII; Rodríguez-Doncel, V., Palmirani, M., Araszkiewicz, M., Casanovas, P., Pagallo, U., Sartor, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 230–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski, S. (Ed.) Agreement Technologies Vol 8. LGT Series; Springer Science & Business Media: Cham, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner, N.; Zeleznikow, J. No sheriff in town: Governance for online dispute resolution. Negot. J. 2016, 32, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.W.; Lane, A.M.; Poblet, M. The Governance of Blockchain Dispute Resolution. Harv. Negot. Law Rev. 2019, 25, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Please note our use of single (‘) and double (“) quotation marks in this paper. We use the former to individuate some terms, or concepts, as is the case in the example above (about ‘legal systems’, ‘legal order’ etc.). We use double quotation marks for literal quotations from other sources. |

| 2 | Gartner Group: Top Technology Trends in Government for 2021, (Retrieved 20 November 2021 from https://www.gartner.com/en/doc/742950-top-technology-trends-in-government-for-2021). |

| 3 | OASIS legalXML specifications, (Retrieved 18 December 2021 from https://legalxml.wpengine.com/) |

| 4 | OASIS LegalRuleML, (Retrieved 18 December 2021 from https://docs.oasis-open.org/legalruleml/legalruleml-core-spec/v1.0/legalruleml-core-spec-v1.0.html) |

| 5 | Cf. the results of the 3rd COHUBICOL (Counting as a Human Being in the Era of Computational Law) Philosophers’ Seminar organised by Mireille Hildebrandt and Laurence Diver on ‘The Legal Effect of Code-driven Law’ in November 2021, especially Palmirani [34] on this subject. |

| 6 | Cf. Kirrane et al. [40]. PoolParty is a semantic technology suite that supports the creation and maintenance of thesauri by domain experts. Rexplore is an interactive environment for exploring scholarly data that leverages data mining, semantic technologies, and visual analytics techniques. Saffron is a topic and taxonomy extraction tool whose main applications include expert finding, document classification and search. |

| 7 | Blijd’s estimation is based on Docusign, Legalzoll, Disco S-1, Intapp S-1, Docusign S-1, NUIX Prospectus, Law Society in relation to their registers SEC filing (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission). |

| 8 | Cf. Intapp S-1 [54] (p. 8) “We believe private capital, investment banking, legal, accounting, and consulting collectively represent a massive industry with $3 trillion in total global revenues, based on research we have conducted. We believe this industry has a significant need to utilise software to help drive business success, with total address-able market for business software at approximately $23.9 billion. We calculate our total addressable market by multiplying the number of firms in the professional and financial services industry by the potential annual contract value of the software solutions used in the business management of such firms, based upon our historical data and experience. We estimate the total number of firms across the private capital, investment banking, legal, accounting, and consulting sectors on a global basis to be approximately 60,000 firms. This figure excludes firms in the professional services industry with fewer than 50 employees, as they are outside of our current target market focus.” |

| 9 | The expression ‘legal entities’ refer to digital entities in relation to the representation languages of the web; this expression is not used here in the usual legal meaning (referred to persons). |

| 10 | Pareto’s principle claims that 80% of effects (sales, revenue, etc.) come from 20% of causes (products, employees, etc.) [56]. These correlations do not hold for the IoT: “Extreme distributions transcend and dominate industry. Fewer than 10% of drinkers, for example, account for over half the hard liquor sold. Even more extreme, less than 0.25% of mobile gamers are responsible for half of all in-game revenue” [56]. |

| 11 | COHUBICOL, (Retrieved 12 November 2021 from https://www.cohubicol.com/about/philosophers-seminar-2021/). |

| 12 | United States Public Company Accounting Reforms and Investor Protection Act (Sarbanes-Oxley Act) 2002, Public Law 107–204, 116 Stat. 745. |

| 13 | Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools, 2003, (Retrieved 16 December 2021 from http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs238.pdf). |

| 14 | Financial Action Task Force (FATF), (Retrieved 16 December 2021 from https://www.fatf-gafi.org/home/). |

| 15 | COBIT 5 identifies five basic principles, seven categories of enablers to govern and manage the information requirements, new process reference model, improved goals and metrics, and aligns with the (ISO/IEC 15504) process capability assessment model and (ISO/IEC 38500) Corporate governance of information technology [111]. |

| 16 | The ISO/IEC standard was revised in 2005, and renumbered (ISO/IEC 27002) in 2007. It was revised again in 2013, and in 2015 the (ISO/IEC 27017) was created to suggest additional security controls for the cloud which were not completely defined in (ISO/IEC 27002). |

| 17 | Cf. Art. 39 Carta Magna (1215). No freemen shall be taken or imprisoned or disseized or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. |

| 18 | —a meaning apparently embraced by Facebook when it re-branded as Meta and launched its “metaverse” in 2021, (Retrieved 18 December 2021 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/metadata). |

| 19 | For a recent systematization, Pohle and Thiel [122], “…The issue is no longer cyber sovereignty as a non-territorial challenge to sovereignty that is specific to the virtual realm of the internet. Today, digital sovereignty has become a much more encompassing concept, addressing not only issues of internet communication and connection but also the much wider digital transformation of societies. Digital sovereignty is—especially in Europe—now often used as a shorthand for an ordered, value-driven, regulated and therefore reasonable and secure digital sphere.” [Ibid. p. 13], see also Floridi [123] advocating for an European “differentiated integration”. |

| 20 | Habermas explicitly allocated rights in the horizontal axis as with “the conceptual move from the horizontal association of consociates who reciprocally accord rights to one another to the vertical organisation of citizens within the state” institutionalises the practice of self-determination” [107] (p. 135). In the Postscript he wrote two years later, he insisted on the social powers of the law, “a ’transmission belt’ that picks up familiar structures of mutual recognition familiar from face-to-face interactions and transmits these, in an abstract but binding form, to the anonymous, systemically mediated interactions among strangers” [124]. |

| 21 | As it is well known by now, Ostrom [125] prioritised the organisation of community relationships at scale, as “the living units exist on a horizontal plane, however, rather than in vertical relationships to one another” [125] (p. 1074). However, in our complex world, Ostrom [126] also asserted that interaction effects often occur among variables at one or more tiers. “Thus, one needs to examine both vertical and horizontal relationships of a partially decomposable conceptual map” [126] (p. 11). |

| 22 | cf. “What is the Rule of Law?”, (Retrieved 16 December 2021 from https://worldjusticeproject.org/about-us/overview/what-rule-law). |

| 23 | Brussels, 25.11.2020 COM(2020) 767 final 2020/0340 (COD) Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on European data governance (Data Governance Act), (Retrieved 14 December 2021 form https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0767). |

| 24 | “For the certification or labelling of trusted data intermediaries, a lower intensity regulatory intervention was envisaged to consist in a softer, voluntary labelling mechanism, where a fitness check of the compliance with the requirements for acquiring the label as well as awarding the label would be carried out by competent authorities designated by Member States (which can also be the one-stop shop mechanisms also established for the enhanced re-use of public sector data).” [Ibid. p. 5]. |

| 25 | Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the accessibility requirements for products and services (Text with EEA relevance) PE/81/2018/REV/1. |

| 26 | See the work by the Open Digital Rights Language Community Group led by Renato Iannella at W3C, (Retrieved 16 December 2021 from https://www.w3.org/community/odrl/). |

| 27 | We identified functional and systemic requirements. The first ones were users’ requirements and led to building functionalities on the https://lynx-project.eu/ (accessed on 27 December 2021) (LYNX) platform. For instance, (i) monitoring law, jurisdictions, regulatory compliance and alert users in case of innovations and legal changes, and (ii) providing access to tax law, labor law, required permits or necessary authorizations and operating licenses (etc.). Systemic requirements were more generic, denoting the properties of the legal ‘ecosystem’ the users intended to deal with. Law firms’ representatives used several narratives to refer to what they expected from the system: “The notion of “customization” of the service, i.e., adaptation to the needs of different end-users, and the metaphor of “radar”, as used in the legal focus group, suggest an intended meaning which is implicit in this kind of narratives: (1). Legal advisors provide a ‘summary’: arguments about key issues to make it easier for the lawyer to choose one strategy or another, taking into account the client’s needs. (2). ‘Our lawyers need to know that they know everything. We are like a radar system. In this regard, we should have a lead on the way the market is developing from a technical or legal perspective’.” [144] (p. 32). |

| 28 | OPTIMAI (https://optimai.eu/ accessed on 27 December 2021): Optimazing Manufacturing Processes through Artificial Intelligence and Virtualization. |

| 29 | I.e., as defined in the Report [12]: “cross-disciplinary and cross-sectorial cooperation—and debate—on the issues of AI, the creation of an European observatory for AI, and of legally deregulated special zones, or living labs, for AI empirical testing—and development for a better interaction between scientists and laymen. By taking into account today’s limited understanding of the stakes of AI, the creation of new type of forums for collective consultation and discussion becomes a priority”. |

| 30 | I.e., as defined in the Report [12]: “the achievement of sustainable development goals, such as capacity building in a good AI society; an interoperable AI strategy between the EU and Member States; a support for the capacity of corporate boards of directors to take responsibility for the ethical implications of companies’ AI technologies; strategies of inclusive innovation; the creation of educational curricula around the impact of AI and a coherent European AI research environment”. |

| 31 | i.e., as defined in the Report [12]: “represent a sort of interface between top-down and bottom-up approaches, that is, between the different forms of engagement and the set of no-regrets actions. These coordination mechanisms include participatory procedures for the alignment of societal values and understanding of public opinion, upstream multi-stakeholder mechanisms for risk mitigation, systems for user-driven benchmarking of marketed AI offerings, cross-disciplinary and cross-sectorial cooperation, and a European observatory for AI to consolidate these forms of coordination. |

| 32 | As proposed by ONTOCHAIN, a New Generation Internet hub for start-up companies. Cf. https://ontochain.ngi.eu/ (accessed on 27 December 2021). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casanovas, P.; de Koker, L.; Hashmi, M. Law, Socio-Legal Governance, the Internet of Things, and Industry 4.0: A Middle-Out/Inside-Out Approach. J 2022, 5, 64-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/j5010005

Casanovas P, de Koker L, Hashmi M. Law, Socio-Legal Governance, the Internet of Things, and Industry 4.0: A Middle-Out/Inside-Out Approach. J. 2022; 5(1):64-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/j5010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasanovas, Pompeu, Louis de Koker, and Mustafa Hashmi. 2022. "Law, Socio-Legal Governance, the Internet of Things, and Industry 4.0: A Middle-Out/Inside-Out Approach" J 5, no. 1: 64-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/j5010005

APA StyleCasanovas, P., de Koker, L., & Hashmi, M. (2022). Law, Socio-Legal Governance, the Internet of Things, and Industry 4.0: A Middle-Out/Inside-Out Approach. J, 5(1), 64-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/j5010005