Rate-Based Modeling and Sensitivity Analysis of Potassium Carbonate Systems for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Industrial Flue Gases

Abstract

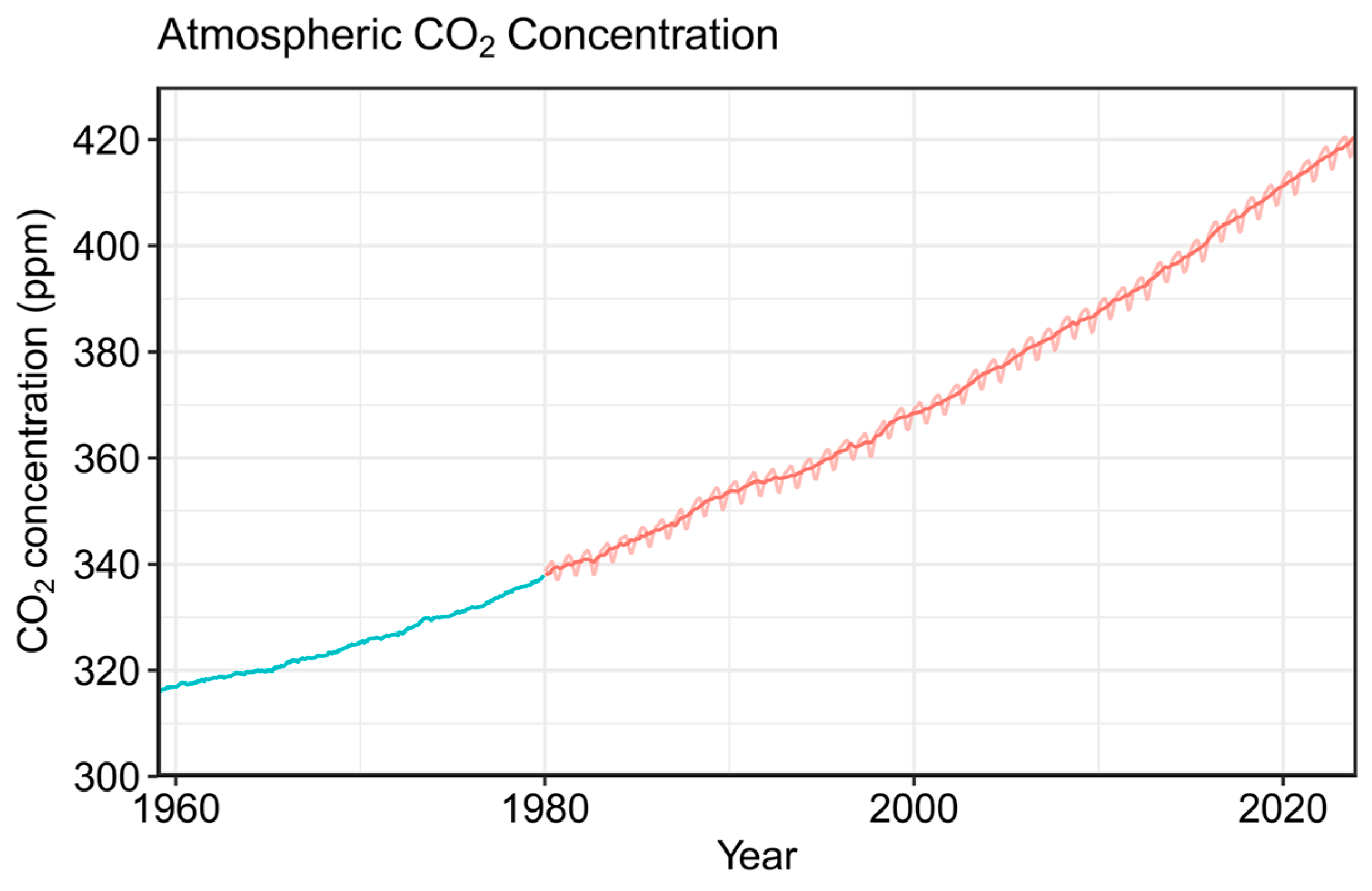

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Process Chemistry

2.2. Process Modelling

2.2.1. Components and Methods

2.2.2. Flue Gas Cases

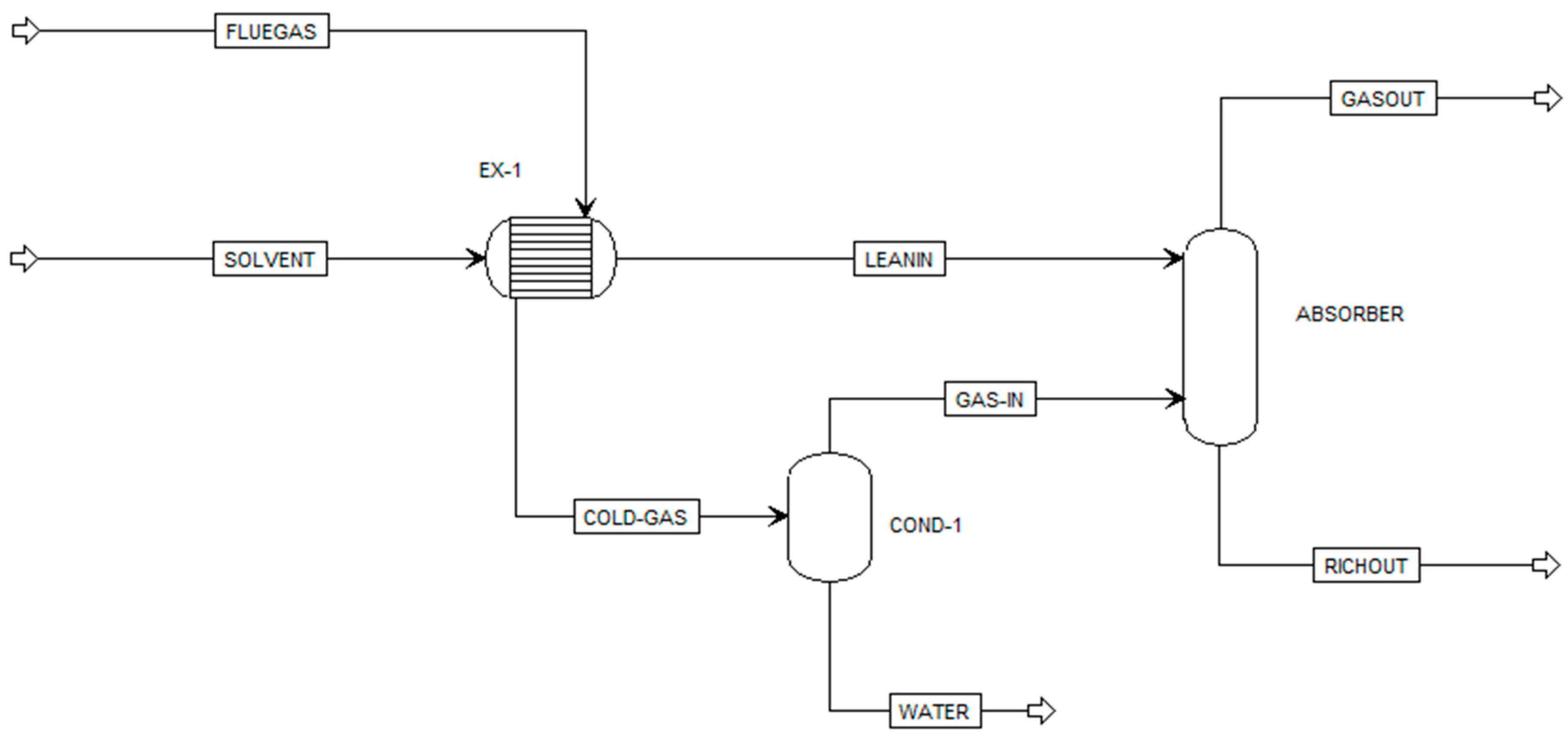

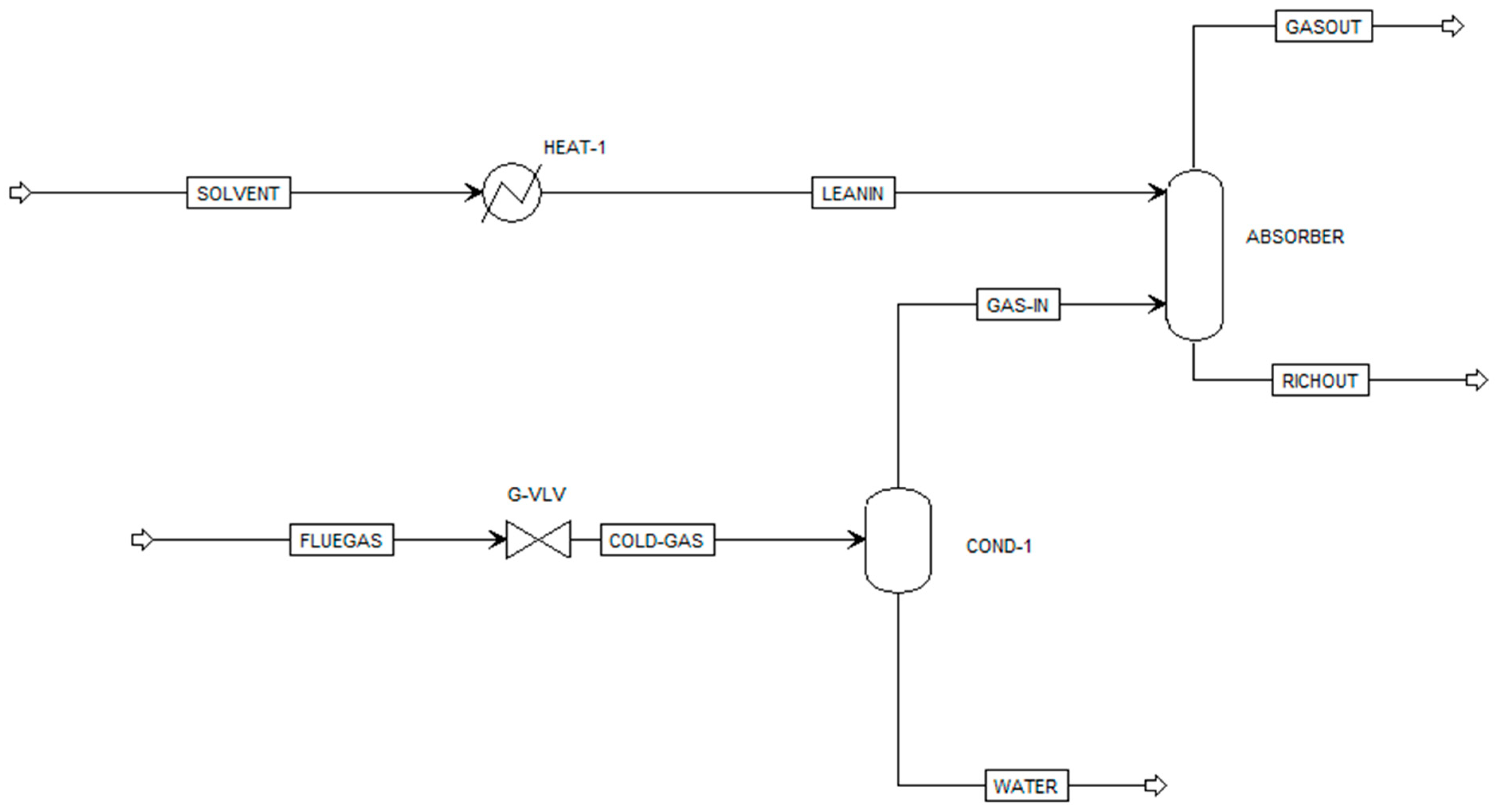

2.2.3. Process Flowsheets

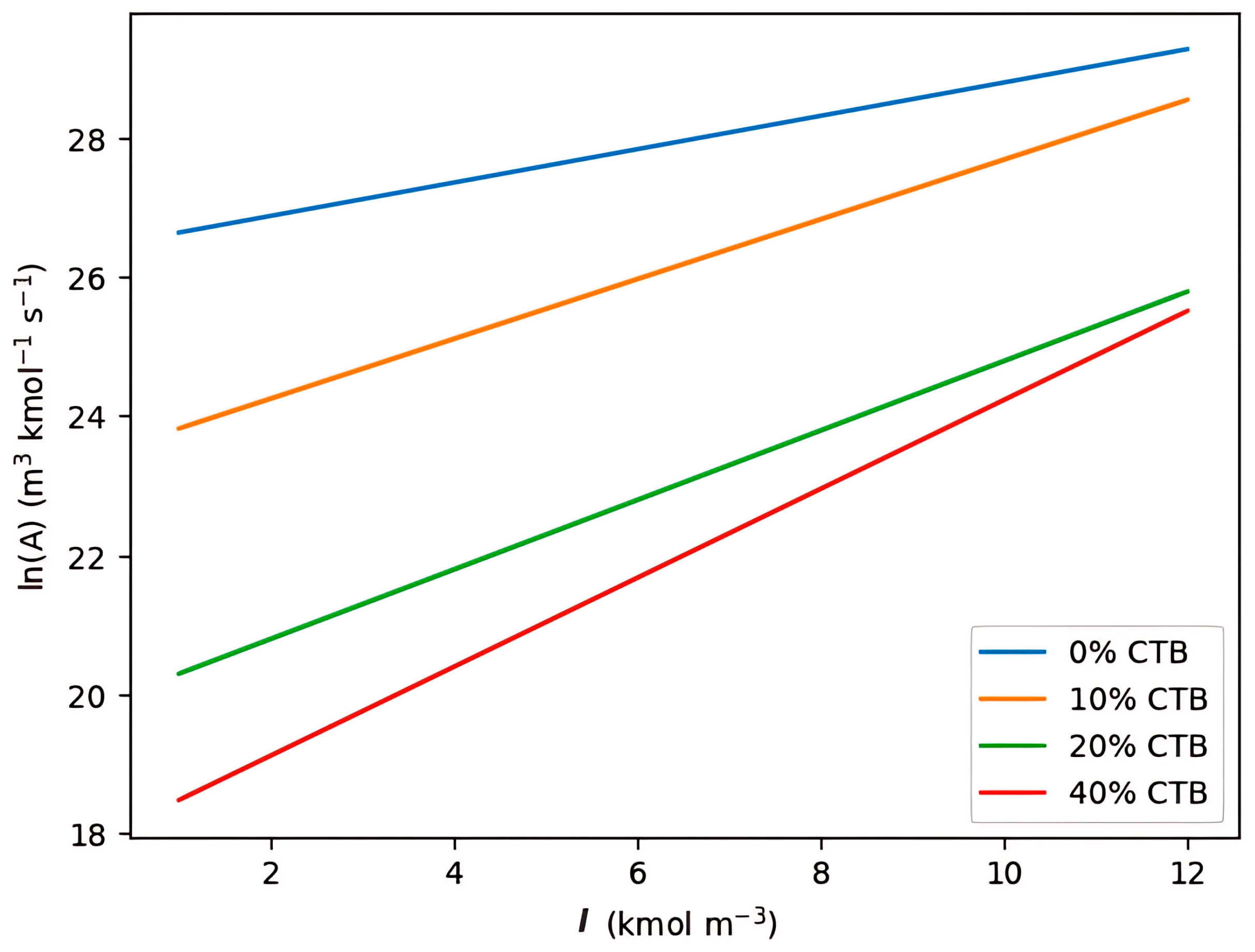

2.2.4. Reaction Kinetics

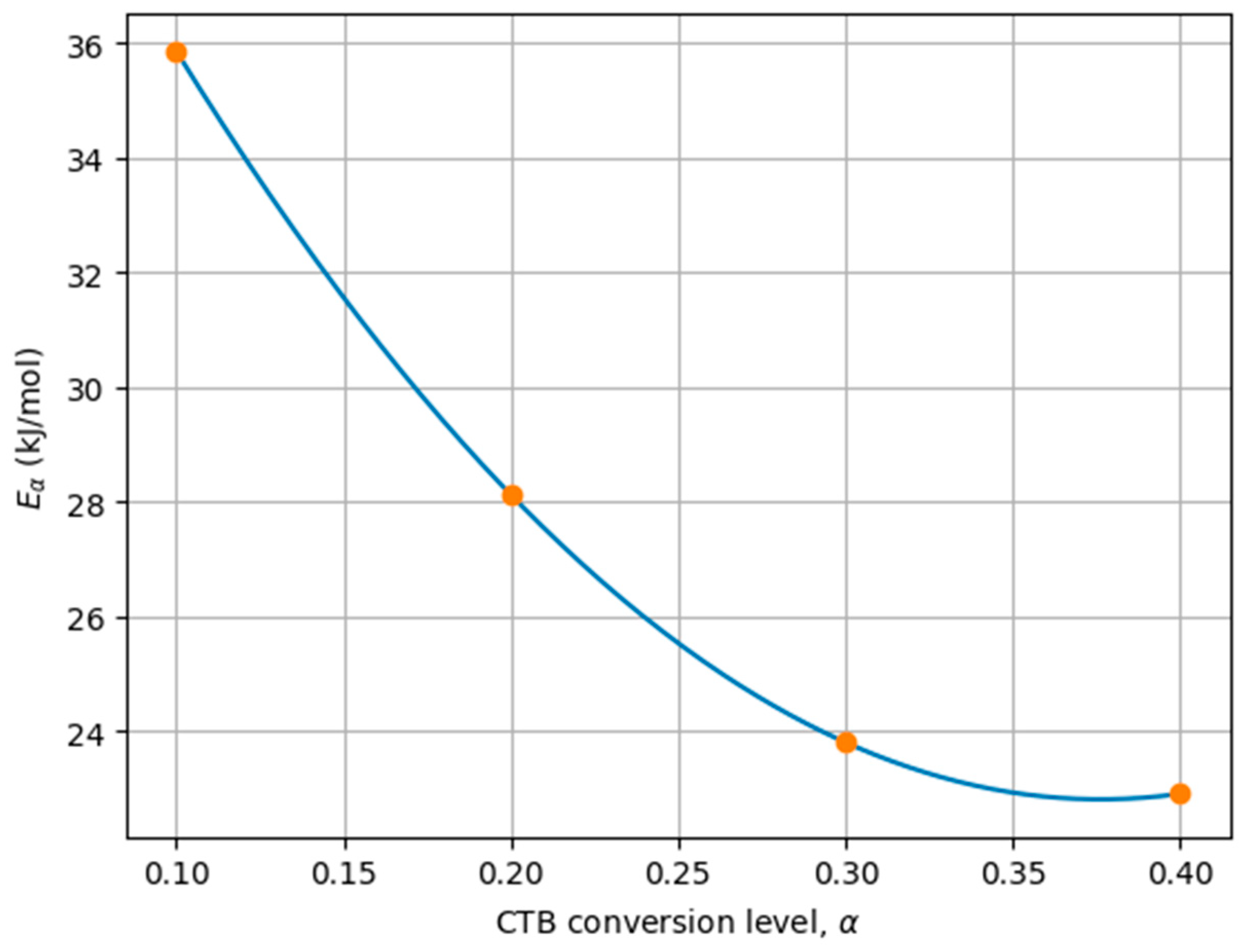

2.2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

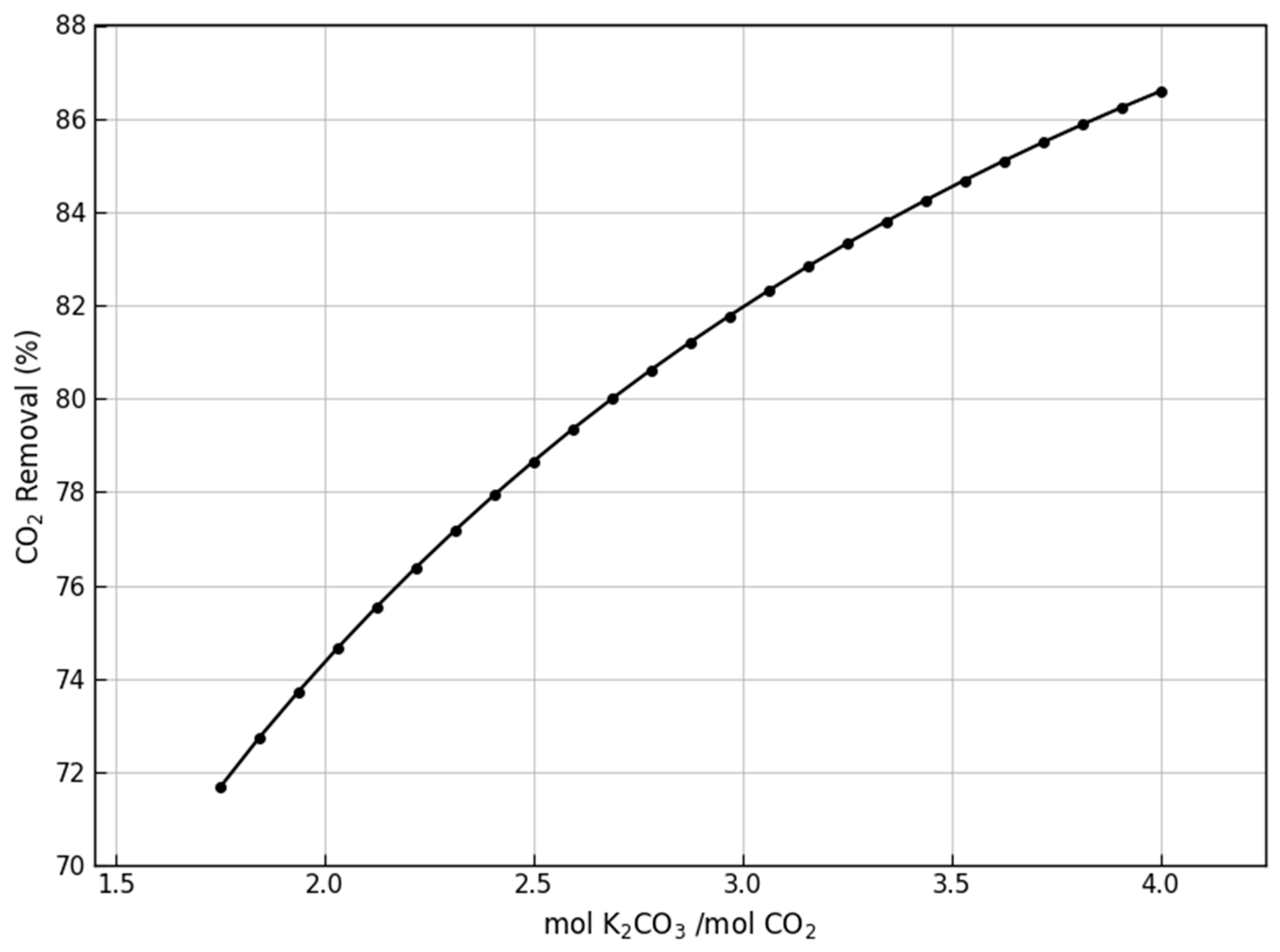

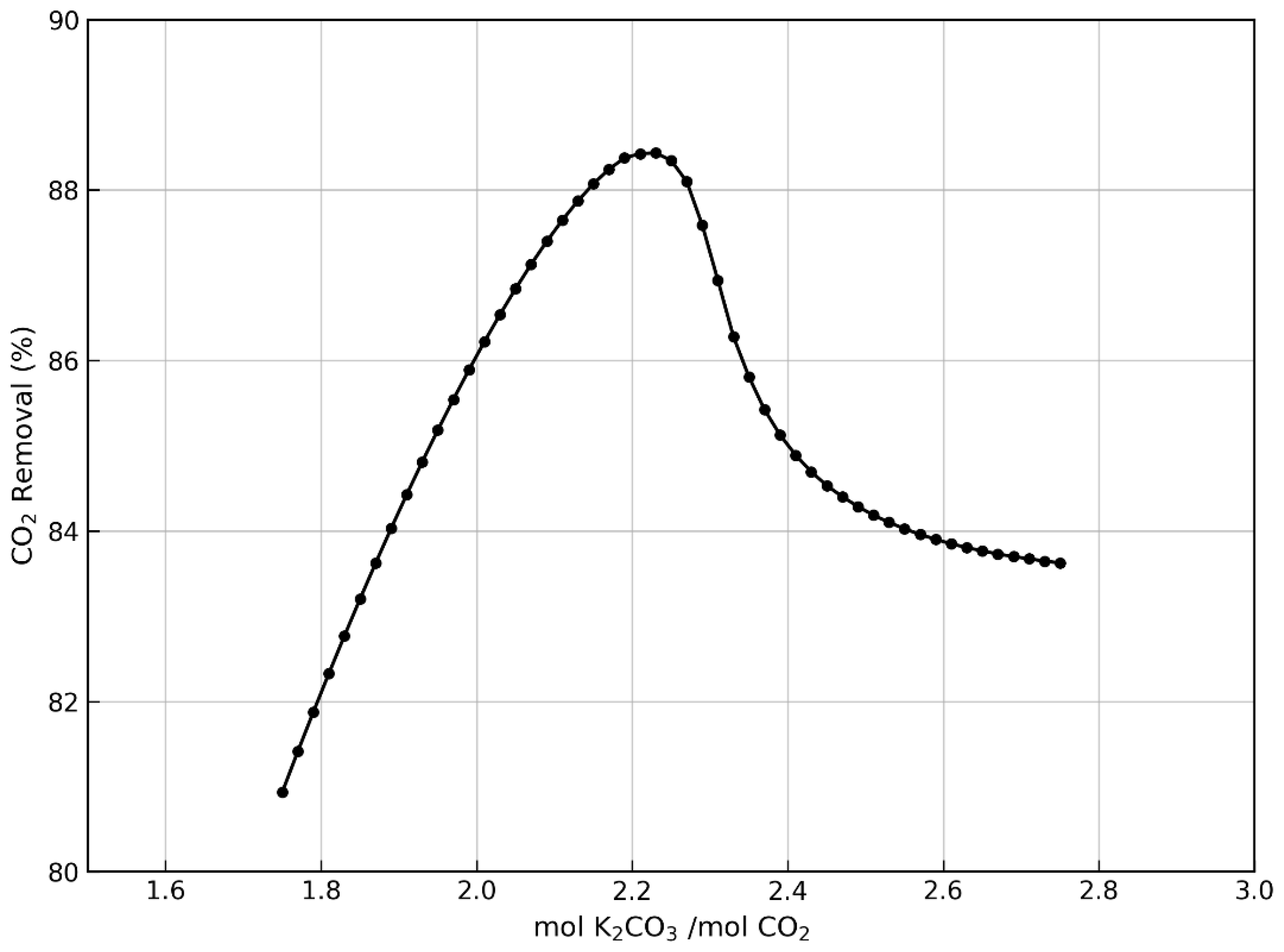

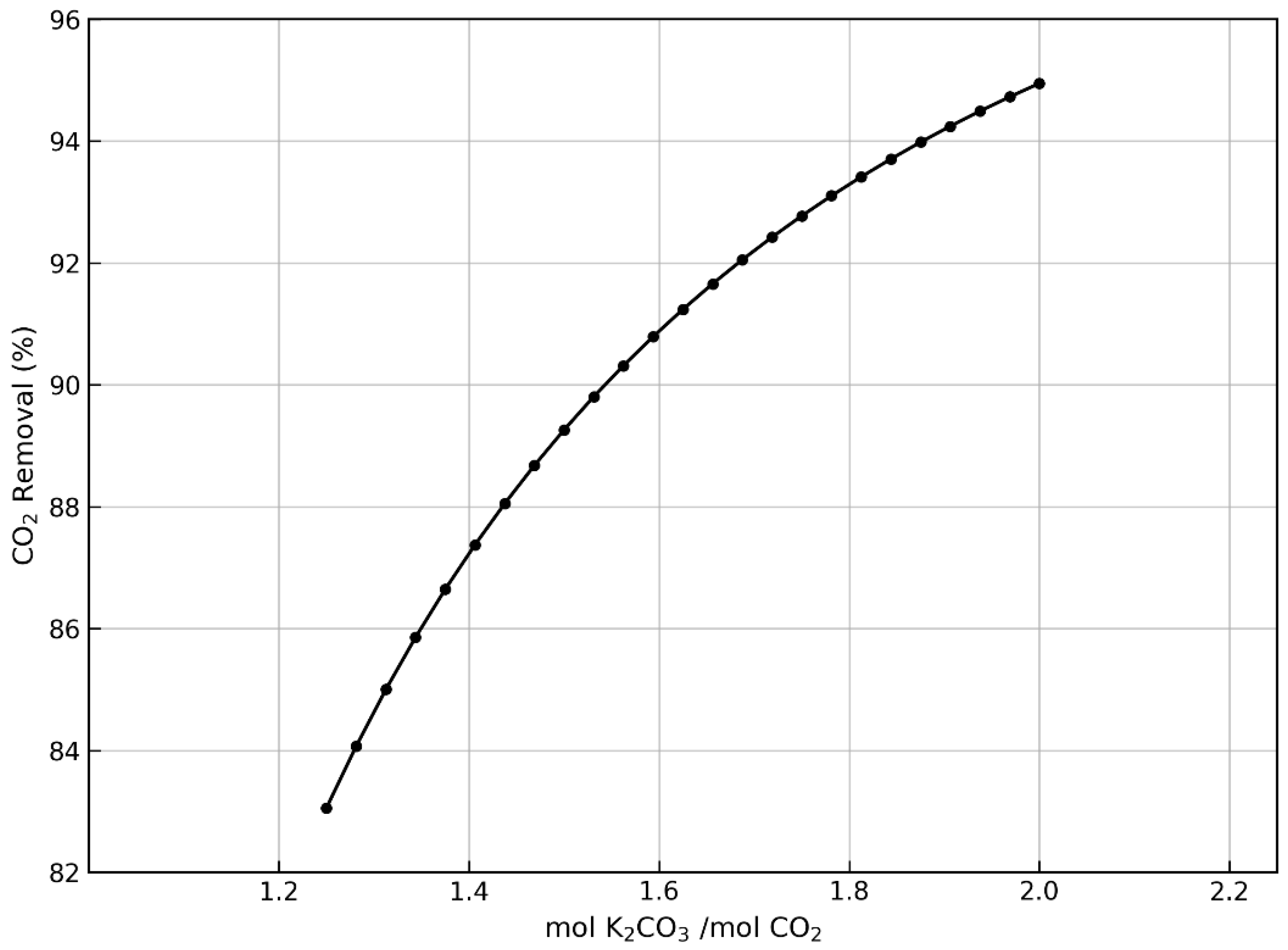

3. Results

3.1. Model Outputs

3.2. Model Validation

3.2.1. Validation Against Pilot-Scale Potassium Carbonate Absorption Studies

3.2.2. Validation Against Demonstration-Scale Potassium Carbonate Processes

3.2.3. Consistency with Independent Aspen Plus Simulation Studies

3.2.4. Overall Validation Assessment

4. Discussion

Limitations and Directions for Future Work

- Experimental validation of absorption and regeneration performance;

- Detailed energy integration and optimization of the regeneration section;

- Comprehensive techno-economic and exergy analyses;

- Systematic investigation of alternative solvent formulations, including different K2CO3 concentrations and carbonate-to-bicarbonate (CTB) conversion levels, to evaluate their impact on cyclic capacity and reboiler duty.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic Digestion |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CCU | Carbon Capture and Utilization |

| CCUS | Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage |

| CTB | Carbonate-to-Bicarbonate Conversion |

| DMEA | Dimethylethanolamine |

| ELECNRTL | Electrolyte Non-Random Two-Liquid Model |

| GJ | Gigajoule |

| GML | Global Monitoring Laboratory |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| L/G | Liquid-to-Gas Ratio |

| MEA | Monoethanolamine |

| PZ | Piperazine |

| RK | Redlich–Kwong Equation of State |

| TGME | Triethylene glycol monomethyl ether |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| VLE | Vapor–Liquid Equilibrium |

References

- Gulev, S.K.; Thorne, P.W.; Ahn, J.; Dentener, F.J.; Domingues, C.M.; Gerland, S.; Gong, D.; Kaufman, D.S.; Nnamchi, H.C.; Quaas, J.; et al. Changing state of the climate system. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 287–422. ISBN 978-1-009-15789-6. Available online: https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/101849/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Lan, X.; Tans, P.; Thoning, K. NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory Trends in Globally-Averaged CO2 Determined from NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory Measurements; Global Monitoring Laboratory: Boulder, CO, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhou, Z. Methods, Progress and Challenges in Global Monitoring of Carbon Emissions from Biomass Combustion. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement. In Proceedings of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21), Paris, France, 12 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. In Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Hanson, E.; Nwakile, C.; Hammed, V.O. Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies: Evaluating the effectiveness of advanced CCUS solutions for reducing CO2 emissions. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 18, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, C.V.T.; Nguyen, N.T.T.; Tran, T.D.; Pham, M.H.T.; Pham, T.Y.T. Capability of carbon fixation in bicarbonate-based and carbon dioxide-based systems by Scenedesmus acuminatus TH04. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 166, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, S.; Chen, J.P. Carbon capture and utilization by algae with high concentration CO2 or bicarbonate as carbon source. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, Z.G.; Dyosiba, X.; Moma, J.; Langmi, H.W.; Louis, B.; Parkhomenko, K.; Musyoka, N.M. Thermocatalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol Using Cu-ZnO Bimetallic Catalysts Supported on Metal–Organic Frameworks. Catalysts 2022, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, X.; Wen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Tao, L.; Li, Q.; Du, S.; Liu, T.; et al. Coupling N2 and CO2 in H2O to synthesize urea under ambient conditions. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Fang, J.; Sun, Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, G.; Ma, T.; Zhi, X. CO2 mineralization of cement-based materials by accelerated CO2 mineralization and its mineralization degree: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 444, 137712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guan, B.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Dang, H.; Chen, L.; Shu, K.; et al. Renewable synthetic fuels: Research progress and development trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raganati, F.; Ammendola, P. CO2 Post-combustion Capture: A Critical Review of Current Technologies and Future Directions. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 13858–13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothandaraman, A. Carbon Dioxide Capture by Chemical Absorption: A Solvent Comparison Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, A.L.; Nielsen, R. Gas Purification; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; ISBN 978-0-08-050720-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tobiesen, A.; Mejdell, T.; Svendsen, H.F. A Comparative Study of Experimental and Modeling Performance Results from the CASTOR Esbjerg Pilot Plant. 2006. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/20847672 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Goff, G.S.; Rochelle, G.T. Oxidation Inhibitors for Copper and Iron Catalyzed Degradation of Monoethanolamine in CO2 Capture Processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 2513–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, N.; Phan, D.; Wang, X.; Conway, W.; Burns, R.; Attalla, M.; Puxty, G.; Maeder, M. Kinetics and Mechanism of Carbamate Formation from CO2(aq), Carbonate Species, and Monoethanolamine in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 5022–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, A.; Rochelle, G.T. Oxidation products of amines in CO2 capture. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies, Trondheim, Norway, 19–22 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stergioudi, F.; Baxevani, A.; Florou, C.; Michailidis, N.; Nessi, E.; Papadopoulos, A.I.; Seferlis, P. Corrosion Behavior of Stainless Steels in CO2 Absorption Process Using Aqueous Solution of Monoethanolamine (MEA). Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2022, 3, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.J.; Verheyen, T.V.; Adeloju, S.B.; Meuleman, E.; Feron, P. Towards Commercial Scale Postcombustion Capture of CO2 with Monoethanolamine Solvent: Key Considerations for Solvent Management and Environmental Impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3643–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, A.; Arora, A. Advancements in carbon capture technologies: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.; Sanna, A.; Navarrete, B.; Maroto-Valer, M.M.; Cortés, V.J. Degradation of amine-based solvents in CO2 capture process by chemical absorption. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 707–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Gao, X.; Gao, G.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Luo, C.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L. A low viscosity and energy saving phase change absorbent of DMEA/MAE/H2O/TGME for post-combustion CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 304, 121058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani, T.N.G.; Azarpour, A.; Akbari, V.; Wan Alwi, S.R.; Manan, Z.A. CO2 capture with potassium carbonate solutions: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 41, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, Q.; Dong, Y.; Lian, S. Effects of different bicarbonate on spirulina in CO2 absorption and microalgae conversion hybrid system. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1119111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.-L.; Chang, J.-S.; Chen, W. Effect of light supply and carbon source on cell growth and cellular composition of a newly isolated microalga Chlorella vulgaris ESP-31. Eng. Life Sci. 2010, 10, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abinandan, S.; Shanthakumar, S. Evaluation of photosynthetic efficacy and CO2 removal of microalgae grown in an enriched bicarbonate medium. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. (Ed.) Energy Efficient Solvents for CO2 Capture by Gas-Liquid Absorption: Compounds, Blends and Advanced Solvent Systems; Green Energy and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, K.; Qi, G.; Frimpong, R.; Nikolic, H.; Liu, K. Aspen modeling for MEA–CO2 loop: Dynamic gridding for accurate column profile. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 37, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Knuutila, H.K.; Gu, S. ASPEN PLUS simulation model for CO2 removal with MEA: Validation of desorption model with experimental data. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4693–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopac, T.; Demirel, Y. Optimizing CO2 capture from biogas: A comparative study of amine-based solvents through Aspen Plus simulations. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 21327–21347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnoon, A.; Hajinezhad, A.; Moosavian, S.F. Simulation model of carbon capture with MEA and the effect of temperature and duty on efficiency. Future Energy 2024, 3, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, D.; Krook-Riekkola, A.; Ji, X. MEA-based CO2 capture: A study focuses on MEA concentrations and process parameters. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1230743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Du, T.; Li, Y.; Yue, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Che, S.; Wang, Y. Techno-economic assessment and exergy analysis of iron and steel plant coupled MEA-CO2 capture process. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, A.; Mendiara, T.; Abad, A.; Adánez, J. Techno-economic analysis of a chemical looping combustion process for biogas generated from livestock farming and agro-industrial waste. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 267, 115865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Biogas Association. EBA Statistical Report 2024; European Biogas Association: Etterbeek, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsent, B.R.W.; Pearson, L.; Roughton, F.J.W. The kinetics of combination of carbon dioxide with hydroxide ions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1956, 52, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohorecki, R.; Moniuk, W. Kinetics of reaction between carbon dioxide and hydroxyl ions in aqueous electrolyte solutions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1988, 43, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-C. Absorption of Carbon Dioxide in a Bubble-Column Scrubber. In Greenhouse Gases—Capturing, Utilization and Reduction; Liu, G., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirs, J.A. Electrometric stopped flow measurements of rapid reactions in solution. Part 2.—Glass electrode pH measurements. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1958, 54, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsent, B.R.W.; Roughton, F.J.W. The kinetics of combination of carbon dioxide with water and hydroxide ions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1951, 47, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelblau, D.M.; Babb, A.L. Kinetic studies of carbonation reactions using radioactive tracers. AIChE J. 1958, 4, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikita, H.; Asai, S.; Takatsuka, T. Absorption of carbon dioxide into aqueous sodium hydroxide and sodium carbonate-bicarbonate solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 1976, 11, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucka, L.; Kenig, E.Y.; Górak, A. Kinetics of the Gas−Liquid Reaction between Carbon Dioxide and Hydroxide Ions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 5952–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lu, Y. Kinetics of CO2 absorption into uncatalyzed potassium carbonate–bicarbonate solutions: Effects of CO2 loading and ionic strength in the solutions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2014, 116, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.; Chenlo, F.; Pereira, G. Enhancement of the Absorption of CO2 in Alkaline Buffers by Organic Solutes: Relation with Degree of Dissociation and Molecular OH Density. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 2353–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldsund, M.; Gardarsdottir, S.O.; De Lena, E.; Pérez-Calvo, J.-F.; Jamali, A.; Berstad, D.; Fu, C.; Romano, M.; Roussanaly, S.; Anantharaman, R.; et al. Comparison of Technologies for CO2 Capture from Cement Production—Part 1: Technical Evaluation. Energies 2019, 12, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelovič, M.; Findura, P.; Jobbágy, J.; Fiantoková, S.; Križan, M. The measurement of gas emissions status during the combustion of wood chips. Savrem. Poljopr. Teh. 2014, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piadeh, F.; Offie, I.; Behzadian, K.; Rizzuto, J.P.; Bywater, A.; Córdoba-Pachón, J.-R.; Walker, M. A critical review for the impact of anaerobic digestion on the sustainable development goals. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barla, R.J.; Raghuvanshi, S.; Gupta, S. Process integration for the biodiesel production from biomitigation of flue gases. In Waste and Biodiesel; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosowska-Golachowska, M.; Luckos, A.; Czakiert, T. Composition of Flue Gases during Oxy-Combustion of Energy Crops in a Circulating Fluidized Bed. Energies 2022, 15, 6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.; Cano, M.; Gallego, L.M.; Camino, S.; Camino, J.A.; Navarrete, B. Evaluation of MEA 5 M performance at different CO2 concentrations of flue gas tested at a CO2 capture lab-scale plant. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 6222–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakel, W.; Hung, C.R.; Tokheim, L.-A.; Strømman, A.H.; Worrell, E.; Ramírez, A. Impact of fuel selection on the environmental performance of post-combustion calcium looping applied to a cement plant. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckebosch, E.; Drouillon, M.; Vervaeren, H. Techniques for transformation of biogas to biomethane. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atnoorkar, S.; Ghosh, T.; Cooney, G.; Carpenter, A.; Benitez, J. Generating Emissions Inventory for Carbon Capture and Storage Analysis for Carbon-Intensive Industrial Sectors. 2023. Available online: https://research-hub.nrel.gov/en/publications/generating-emissions-inventory-for-carbon-capture-and-storage-ana/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Onda, K.; Takeuchi, H.; Okumoto, Y. Mass Transfer Coefficients Between Gas and Liquid Phases in Packed Columns. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1968, 1, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichlmair, J.; Bravo, J.L.; Fair, J.R. General model for prediction of pressure drop and capacity of countercurrent gas/liquid packed columns. Gas Sep. Purif. 1989, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Yang, L.; Du, X.; Yang, Y. CO2 capture using MEA (monoethanolamine) aqueous solution in coal-fired power plants: Modeling and optimization of the absorbing columns. Energy 2016, 109, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.; Nittaya, T.; Douglas, P.L.; Croiset, E.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.A. Dynamic simulation of MEA absorption process for CO2 capture from power plants. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2012, 10, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, F.; Hamad, E.; Traver, M.; Kalamaras, C. Amine-based CO2 capture on-board of marine ships: A comparison between MEA and MDEA/PZ aqueous solvents. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2024, 135, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffer, A.; Brechtel, K.; Scheffknecht, G. Comparative study on differently concentrated aqueous solutions of MEA and TETA for CO2 capture from flue gases. Fuel 2012, 101, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.H.; Anderson, C.J.; Tao, W.; Endo, K.; Mumford, K.A.; Kentish, S.E.; Qader, A.; Hooper, B.; Stevens, G.W. Pre-combustion capture of CO2—Results from solvent absorption pilot plant trials using 30 wt% potassium carbonate and boric acid promoted potassium carbonate solvent. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2012, 10, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Xiao, G.; Mumford, K.; Gouw, J.; Indrawan, I.; Thanumurthy, N.; Quyn, D.; Cuthbertson, R.; Rayer, A.; Nicholas, N.; et al. Demonstration of a Concentrated Potassium Carbonate Process for CO2 Capture. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenphan, T.; Yurata, T.; Sema, T.; Chalermsinsuwan, B. Techno-economic sensitivity analysis for optimization of carbon dioxide capture process by potassium carbonate solution. Energy 2022, 254, 124290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component ID | Type | Component Name | Alias |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | Conventional | WATER | H2O |

| CO2 | Conventional | CARBON-DIOXIDE | CO2 |

| N2 | Conventional | NITROGEN | N2 |

| O2 | Conventional | OXYGEN | O2 |

| CH4 | Conventional | METHANE | CH4 |

| K2CO3 | Conventional | POTASSIUM-CARBONATE | K2CO3 |

| KHCO3 | Conventional | POTASSIUM-BICARBONATE | KHCO3 |

| HCO3− | Conventional | HCO3− | HCO3− |

| CO3−2 | Conventional | CO3−− | CO3−2 |

| K+ | Conventional | K+ | K+ |

| H3O+ | Conventional | H3O+ | H3O+ |

| OH− | Conventional | OH− | OH− |

| Parameter | Cement Plant [50] | Biomass Combustion [51] | Anaerobic Digestion Plant [52] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass rate (kg/h) | 3344.9 | 2972.7 | 3718.7 |

| Temperature (°C) | 130 | 130 | 35 |

| Pressure (bar) | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Mol fractions | |||

| H2O | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.05 |

| CO2 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.35 |

| N2 | 0.6 | 0.66 | - |

| O2 | 0.07 | 0.08 | - |

| CH4 | - | - | 0.6 |

| Specification | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| Number of stages | 18 |

| Operating pressure | 1 bar |

| Re-boiler | None |

| Condenser | None |

| Packing type | Berl saddles, ceramic, 13 mm |

| Packing height range | 18–25 m |

| Packing diameter | 1.2 m (1.6 m for AD unit) |

| Reaction condition factor | 0.9 * |

| Mass transfer coefficient | Onda68 [59] |

| Interfacial area method | Onda68 [59] |

| Interfacial area factor | 2 |

| Heat transfer coefficient method | Chilton and Colburn |

| Holdup correlation | Stichlmair89 [60] |

| Liquid film resistance | Discretization, 5 points |

| Vapor film resistance | Film consideration |

| Flow model | Mixed |

| Parameter | Kinetic Factor | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Equation (3) | 1.1458 × 1011 | 35.89 |

| Equation (4) | 2.83 × 1017 | 123.3 |

| Parameter | Aj | Bj | Cj | Dj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (5) | 132.899 | −13,445.9 | −22.4773 | 0 |

| Equation (8) | 216.049 | −12,431.7 | −35.4819 | 0 |

| Parameter | Cement Plant | Biomass Combustion | Anaerobic Digestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| mol K2CO3/mol CO2 | 1.75–4.00 | 1.75–2.75 | 1.25–2.00 |

| Mass flow (kg/h) | 27,408.4–43,070.4 | 8155.8–12,816.2 | 44,743.2–71,589.1 |

| Solvent/Gas mass ratio | 8.19–12.88 | 2.74–4.31 | 12.03–19.25 |

| Column height (m) | 20–25 | 18–23 | 18–23 |

| Temperature (°C) | 24.5–23.2 | 47.8–41.6 | 45 |

| Concentration wt% | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Scenario | Cement Industry | Biomass Combustion | Anaerobic Digestion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint | Min. Height | Min. L/G | Min. Height | Min. L/G | Min. Height | Min. L/G |

| Column height (m) | 22 | 25 | 19 | 23 | 18 | 20 |

| mol K2CO3/mol CO2 | 4.00 | 3.34 | 2.21 | 1.89 | 1.53 | 1.41 |

| Solvent/Gas mass ratio | 12.88 | 11.50 | 3.46 | 2.96 | 15.92 | 14.21 |

| CO2 Removal (%) | 89.82 | 90.17 | 89.86 | 90.03 | 89.80 | 89.97 |

| Scenario | Cement Industry | Biomass Combustion | Anaerobic Digestion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint | Min. Height | Min. L/G | Min. Height | Min. L/G | Min. Height | Min. L/G |

| Column height (m) | 22 | 25 | 19 | 23 | 18 | 20 |

| mol CO2/mol K2CO3 | 0.275 | 0.261 | 0.223 | 0.284 | 0.354 | 0.372 |

| Specific reboiler duty (GJ/tonCO2) | 3.72 | 3.47 | 4.15 | 3.94 | 2.69 | 2.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pachakis, G.; Mai, S.; Barampouti, E.M.; Malamis, D. Rate-Based Modeling and Sensitivity Analysis of Potassium Carbonate Systems for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Industrial Flue Gases. Clean Technol. 2026, 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010014

Pachakis G, Mai S, Barampouti EM, Malamis D. Rate-Based Modeling and Sensitivity Analysis of Potassium Carbonate Systems for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Industrial Flue Gases. Clean Technologies. 2026; 8(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010014

Chicago/Turabian StylePachakis, Giannis, Sofia Mai, Elli Maria Barampouti, and Dimitris Malamis. 2026. "Rate-Based Modeling and Sensitivity Analysis of Potassium Carbonate Systems for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Industrial Flue Gases" Clean Technologies 8, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010014

APA StylePachakis, G., Mai, S., Barampouti, E. M., & Malamis, D. (2026). Rate-Based Modeling and Sensitivity Analysis of Potassium Carbonate Systems for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Industrial Flue Gases. Clean Technologies, 8(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010014