Integrating Rooftop Grid-Connected Photovoltaic and Battery Systems to Reduce Environmental Impacts in Agro-Industrial Activities with a Focus on Extra Virgin Olive Oil Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Environmental Analysis and Trade-Off

1.2. Novelties and Specific Objectives

- Limited investigation of agrisolar systems involving PV applications in olive oil production and a limited understanding of their potential in the agro-industrial sector;

- Lack of an in-depth analysis of agro-industrial energy consumption based on hourly evaluation and for the related under-explored use of intermittent renewable sources;

- Lack of an accurate methodology to assess the environmental impact of the agro-industrial energy system;

- The utilisation of BESS and PV systems within olive mills represents a strategy for the integration of renewable energy in agro-industrial activities that has not yet been explored.

- Firstly, this study applies the CF methodology for evaluating PV energy potential in mitigating carbon emissions for agro-industrial activities.

- PV and BESS integration in the context of existing olive oil mills is studied by defining a practical and replicable methodology for integrating renewable energy sources into existing agro-industrial activities.

- Another novel methodological approach is represented by the site-specific evaluation of PV energy production within critical factors assessment, rather than relying solely on pre-formulated PV system data from LCA databases.

- The development of an hourly energy consumption evaluation algorithm and the application of CF methodology provide a replicable framework for other agro-industrial facilities.

- defining PV and BESS design parameters, to minimise the CF of EVOO production;

- implementing an algorithm to simulate PV+BESS system interaction on an hourly basis;

- performing an overall assessment of optimal conditions for reducing CF in EVOO production, with regard to the PV and PV+BESS system.

2. Materials and Methods

- The first step started from the definition of the case studies, described in Section 2.1, where data acquisition and software for solar irradiation (PVGIS) were included.

- The second step encompassed the definition of CF methodology in its main features, namely the functional unit, CF software, system boundaries, and scenarios, described in Section 2.2. This research study developed a comparative approach between 3 different scenarios applied to specific case studies. In the baseline scenario, the mill is not energy-producing and thus relies on the NG for its energy requirements (SNG). The second and third scenarios involved a grid-connected PV system, where part of the energy consumed is taken from the grid and part of the energy produced is fed in. While in the second scenario (SPV), the energy produced and not immediately self-consumed is fed into the grid, in the third scenario (SPV+B), the energy not immediately self-consumed is stored in the battery for later consumption.

- In the third step, main unitary features of the PV and BESS were defined, as described in Section 2.3. The parameters under consideration included the peak power of the panels, the dimensions, the power of the inverters, the mounting criterion, the lifetime, and the weight.

- The fourth step in the process was the implementation of an algorithm that simulates the interaction between NG, PV, and BESS, as described in 2.4. This algorithm was designed to compute: the invariant of the self-consumed energy, the total energy produced by PV, the energy stored by the battery, and the energy fed into the grid. The sizing of the battery in the PV+BESS system is therefore determined by assuming the minimisation of CF in the SPV+B.

- The fifth step was related to the implementation of the inventory, as described in Section 2.5. It consists of literature data from the actual case studies and the energy quantities obtained as a result of the implementation of the algorithm.

2.1. Data Acquisition and Software

- The industrial phase includes primary and secondary packaging. In this regard, previous studies have shown how this is a particularly energy-intensive phase that contributes significantly to GHG emissions [44,46,47]. In this study, the utilisation of the aforementioned packaging data facilitated the formulation of more in-depth assessments of the reduction in the PV system impact.

- The mills have been geo-localised; thus, the location of the existing buildings under study provided an opportunity to examine the feasibility of simulating the location of agrisolar systems on their rooftops. However, the irradiation conditions are generally sub-optimal due to the orientation, slope, and size of the roof of the existing agro-industrial buildings.

- Electricity consumption data were measured in situ by using a multimeter installed at the electrical control. This methodology enabled the analysis of activities related to olive oil processing, while excluding those related to air conditioning and lighting. This approach also ensured the reduction of errors due to estimation of energy consumption.

- The case studies include different technological and structural peculiarities, quite representative of a variety that can be found in Italy and all over the world. They differ among themselves, for instance, in the extension of the cultivated fields, harvesting methods, oil extraction techniques, size of the mill, and packaging adopted. All these characteristics have an impact on the farm’s consumption profile, to the extent that a higher production volume leads to lower energy expenditure per unit of production, but equally, different techniques have different consumption characteristics. For example, 2-phase extraction requires less energy consumption than 3-phase but only for high production volumes [41,48].

- The oil mills are located in central Italy, so they represent a good trade-off of the average conditions in terms of energy performance between the North of Italy, where energy production would be lower, and the South of Italy, where increased energy production would increase the total performance of the energy system, thus reducing CF.

- -

- Orientation, slope, latitude, and roof area available. These are all conditions related to the structure of the agro-industrial building and the geographical location. Optimal conditions at the latitude of approximately 42°N (Abruzzi), as earlier mentioned, would require a southern exposure with a slope of approximately 35°;

- -

- Installation and maintenance constitute another type of dimensional problem. In fact, the plant layout must provide the necessary space for professional installation and maintenance activities, thus producing a reduction in the usable surface area of the PV system;

- -

- The percentage of self-consumed renewable energy compared to that supplied by the NG. It depends on the typical consumption profile of the mill, the production method used, and the presence of a BESS.

2.2. Scenarios and CF Computation Methodology

- Three different scenarios were analysed for each case study:

- SNG: Ec only supplied by ENG,

- SPV: Ec supplied by ENG and EPV mix,

- SPV+B: Ec supplied by ENG, EPV, and EB.

2.3. Photovoltaic System and Battery Specifications

- Grid-connected PV system;

- Single-Si modules of 1 × 1.9 (m × m);

- PV panels feature: 30-year lifetime 0.43 kWp Solar panels, and 15-year lifetime inverters (from 2.5 to 50 kW) with yearly maintenance;

- Total energy losses of the system, caused by losses in cables, power inverters, dirt (e.g., particulate matter, snow, and sand) on the modules, and loss of module power over the years, are set at 14%;

- For the flat rooftop system (Figure 4b), the modules are installed with a 2 m pitch, defined by the distance between the centres of the modules, in such a way that the entire available area is occupied. The place between modules (Z) comes from the minimisation of the losses caused by module shadowing based on the solar height (υ) at the mean latitude of Abruzzi (φ = 42.102718), according to Equations (6) and (7):

2.4. Grid-Connected PV System, National Grid and Battery Interactions

- CBESS = Maximum battery state of charge in kWh. In the different simulations carried out, the CBESS value varied from 5 to 200 kWh in order to find the lowest environmental impact of the system.

- acc = 0 indicates the initial state of charge of the battery.

- ENG = 0 indicates the initial energy required from the NG.

- EOut = 0 indicates the initial energy fed into the NG.

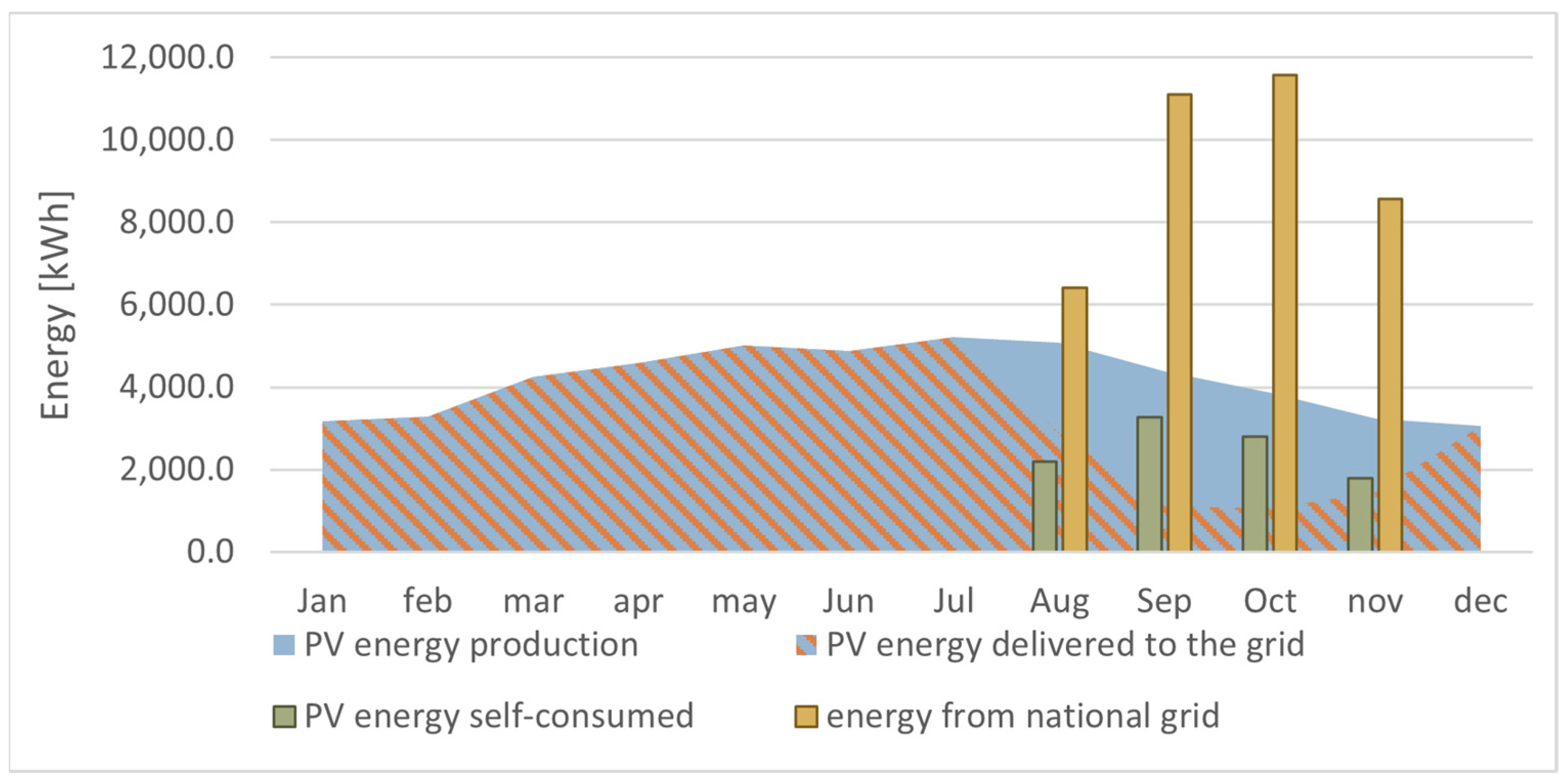

- PV production and mill consumption were calculated and matched on an hourly basis, assuming that the typical daily load pattern repeats throughout the milling season (September–December).

- The algorithm assumes that the hourly consumption profile is fixed within the milling season and does not account for daily variability due to processing delays or operational changes.

- PV energy exceeding the battery storage capacity or instantaneous consumption is considered fed into the grid (EOut), with no curtailment.

- Energy is first used to meet current consumption, then to charge the battery, and finally, any surplus is exported to the grid.

- An overall 14% system loss was applied to annual PV output.

- It is assumed that the objective is not to maximise the economic and financial indicators but to minimise the CF.

2.5. Inventory Analysis

2.6. Economic Assessments

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Results of Grid-Connected PV System and Battery Interaction

3.2. CF Results

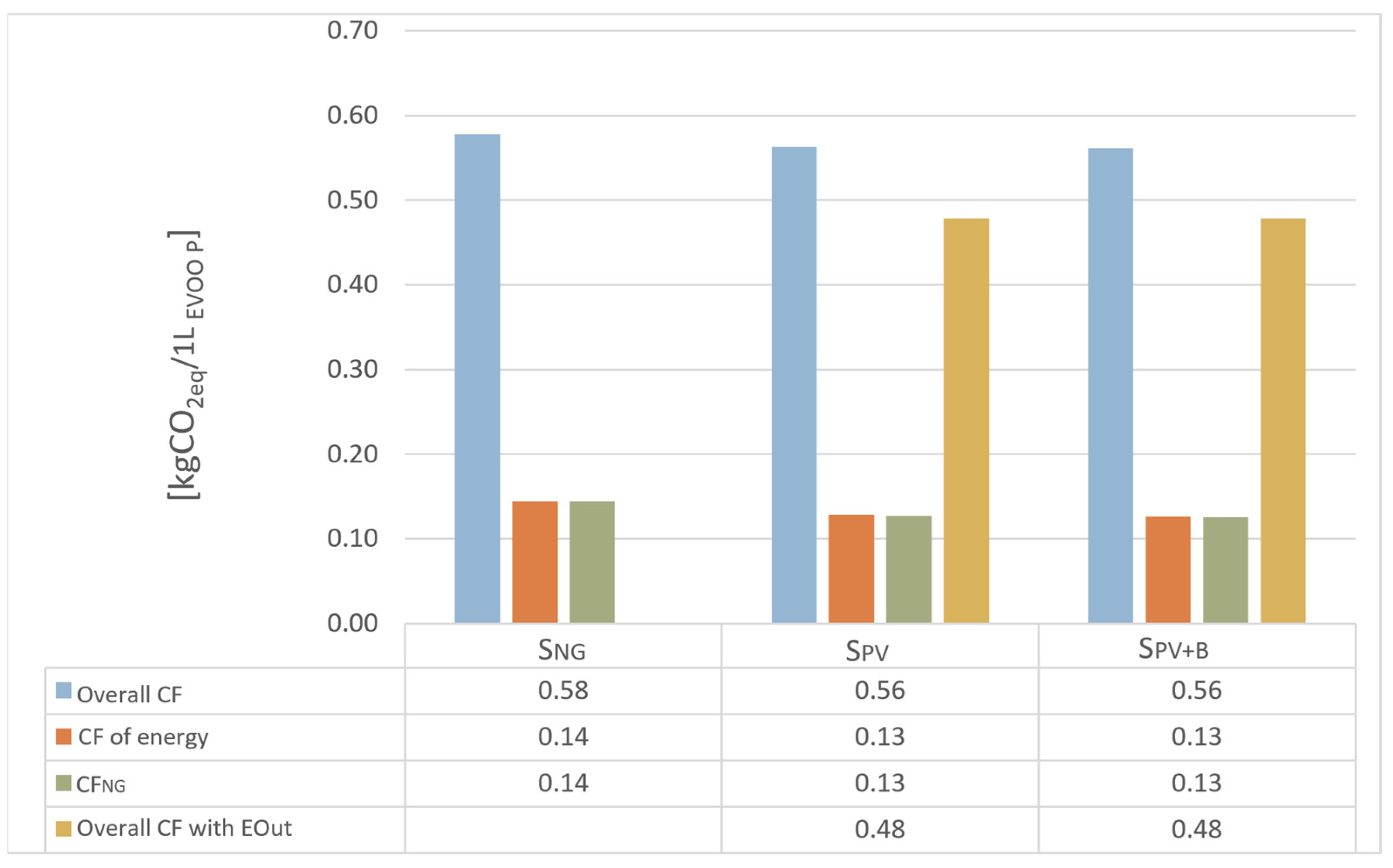

3.2.1. Case Study 1

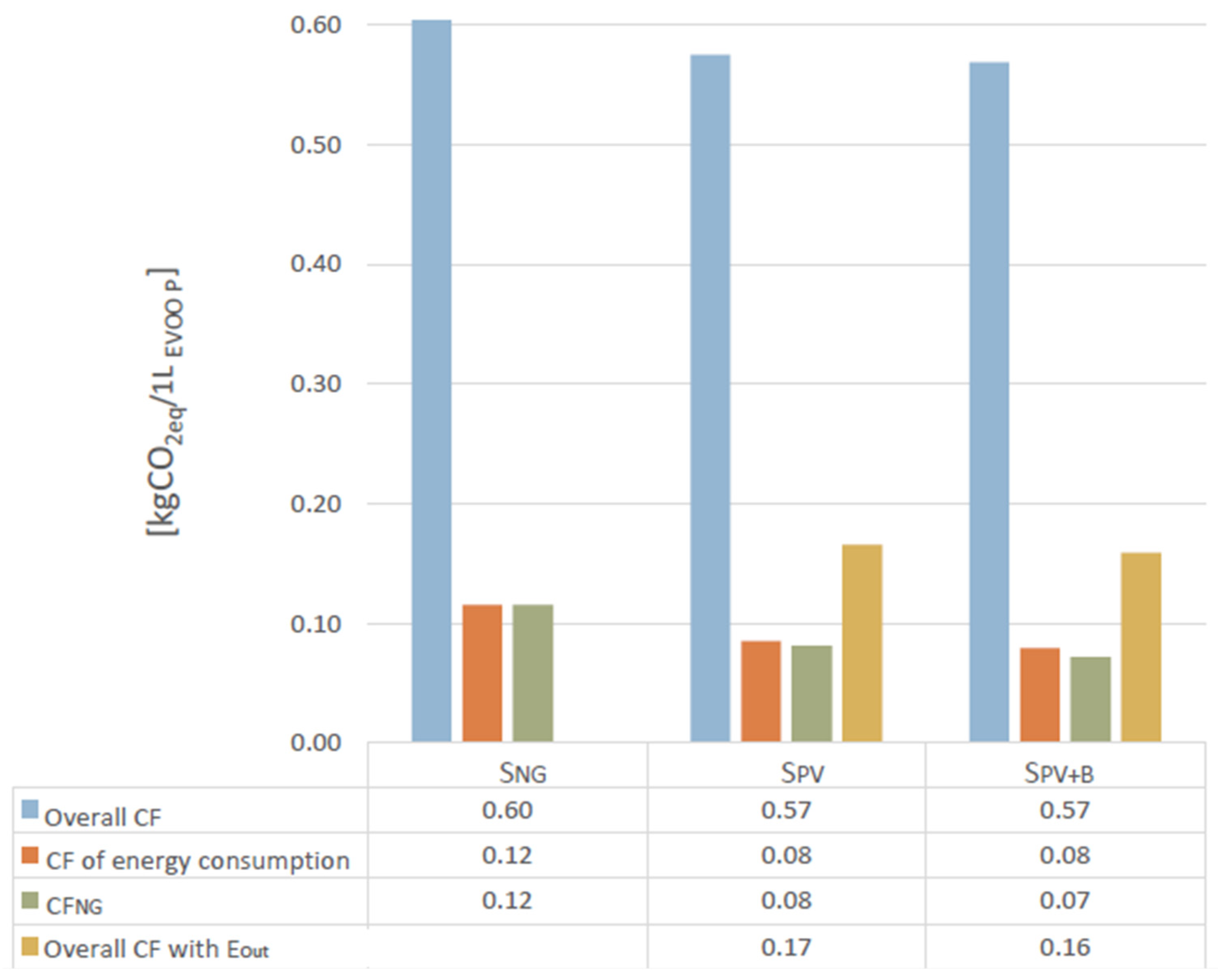

3.2.2. Case Study 2

3.2.3. Case Study 3

- The higher environmental impact of flat rooftop PV plants which requires a higher amount of metal and energy for the PV system installation.

3.2.4. Case Study 4

3.2.5. Case Study 5

3.3. Economical Assessments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| acc | Battery state of charge counter |

| BESS | Battery energy storage system |

| CBESS | Battery energy maximum capacity |

| CEN | Covered energy needs |

| CF | Carbon Footprint |

| CFPV | CF associated with PV system on Function unit base |

| CNG | CF associated with NG energy consumption on Function unit base |

| CFB | CF associated with BESS usage on Function unit base |

| CF_EOut | CF associated with PV system on Function unit base |

| Cb | the amount of equivalent CO2 produced for battery production, transportation and dismission |

| IBESS | (WB *1-1) * Qolives−1 |

| IPV | Lifetime*capacity*annual yield |

| EB | PV Energy stored by BESS and self-consumed by olive mill |

| Ec (h, m) | Ec (0 To 23, 1 To 12) Hourly energy requested by olive mill. |

| ENG | Electric energy requested by NG |

| EOut | Energy delivered to the NG |

| EOut,act | Energy delivered to the NG in the days of activity |

| Ep (h, m) | Ep (0 To 23, 1 To 12) Hourly energy produced by PV |

| EPV | PV Energy produced and self-consumed by olive mill |

| ER | Renewable energy. EPV + EB |

| EVOO | Extra Virgin Olive Oil |

| FU | Functional unit |

| g | Current day |

| g_m (m) | g_m (1 To 12) days in a month |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| H | Current hour |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| m | Current month |

| NG | National grid |

| PBT | Payback time |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PV+BESS | Integration of PV and BESS system |

| Qolives | Olives milled in a year |

| SDG | Sustainable Development goal |

| SNG | The scenario in which Ec is only supplied by NG |

| SPV | The scenario in which Ec is supplied by NG and PV mix, |

| SPV+B | The scenario in which Ec is supplied by NG, PV, and battery |

| WB | Battery total weight |

References

- Chen, B.; Xiong, R.; Li, H.; Sun, Q.; Yang, J. Pathways for Sustainable Energy Transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassar, A.A.A.; Cha, S.H. Review of Geographic Information Systems-Based Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Potential Estimation Approaches at Urban Scales. Appl. Energy 2021, 291, 116817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Tu, Z.; Chan, S.H. A Novel Flexible Load Regulation and 4E-F Multi-Objective Optimization for Distributed Renewable Energy Power Generation System. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, G.; Pulvirenti, A.; Spina, D.; Bracco, S.; D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G. Clustering Olive Oil Mills through a Spatial and Economic GIS-Based Approach. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 14, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISMEA. Available online: https://www.Ismeamercati.It/Flex/Cm/Pages/ServeBLOB.Php/L/IT/IDPagina/4040 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C.; De Pascale, A. Economic Analysis and Energy Valorization of By-Products of the Olive Oil Process: “Valdemone DOP” Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonetti, F.; Martelli, F.; Resta, G. Artificial Neural Networks Applied to Olive Oil Production and Characterization: A Systematic Review. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovenzana, V.; Beghi, R.; Romaniello, R.; Tamborrino, A.; Guidetti, R.; Leone, A. Use of Visible and near Infrared Spectroscopy with a View to On-Line Evaluation of Oil Content during Olive Processing. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 172, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A.; Romaniello, R.; Zagaria, R.; Sabella, E. Specification and Implementation of a Continuous Microwave-Assisted System for Paste Malaxation in an Olive Oil Extraction Plant. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 125, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborrino, A.; Leone, A.; Romaniello, R.; Catalano, P.; Bianchi, B. Comparative Experiments to Assess the Performance of an Innovative Horizontal Centrifuge Working in a Continuous Olive Oil Plant. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 129, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSE—Gestore dei Servizi Energetici. Bando 1/2022 del Parco Agrisolare. Available online: https://www.gse.it/servizi-per-te/attuazione-misure-pnrr/parco-agrisolare/bando-1-2022 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Luthra, S.; Rimoldi, L. Agrisolar, Incentives and Sustainability: Profitability Analysis of a Photovoltaic System Integrated with a Storage System. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.J.; Imalka, S.T.; Wijeratne, W.M.P.; Amarasinghe, G.; Weerasinghe, N.; Jayakumari, S.D.S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Gunarathna, C.; Perrie, J.; et al. Digitalizing Building Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Conceptual Design: A Framework and an Example Platform. Build. Environ. 2023, 243, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, S.; Cao, H. Study on the Optimal Layout of Roof Vents and Rooftop Photovoltaic of the Industrial Workshop. Build. Environ. 2024, 260, 111624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, B.; Torcellini, P.; Long, N.; Crawley, D.; Ryan, J. Assessment of the Technical Potential for Achieving Zero-Energy Commercial Buildings. In Proceedings of the ACEEE Summer Study, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 13–18 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cinardi, G.; D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cascone, G. Integrating Photovoltaic Systems to Reduce Carbon Footprint in Extra Virgin Olive Oil Production: A Territorial Perspective in the Mediterranean Area. In Biosystems Engineering Promoting Resilience to Climate Change—AIIA 2024—Mid-Term Conference; Sartori, L., Tarolli, P., Guerrini, L., Zuecco, G., Pezzuolo, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 586, pp. 999–1007. ISBN 978-3-031-84211-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan Satpathy, P.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Roslan, M.F.; Motahhir, S. An Adaptive Architecture for Strategic Enhancement of Energy Yield in Shading Sensitive Building-Applied Photovoltaic Systems under Real-Time Environments. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaza, O.; Contreras-Montes, J.; García-Ruiz, M.J.; Delgado-Ramos, F.; Gómez-Lorente, D. Techno-Economic Performance Evaluation for Olive Mills Powered by Grid-Connected Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2015, 8, 11939–11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakir, A.; Tabaa, M.; Moutaouakkil, F.; Medromi, H.; Julien-Salame, M.; Dandache, A.; Alami, K. Optimal Energy Management for a Grid Connected PV-Battery System. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukisa, N.; Zamora, R. Optimal Tilt Angle for Solar Photovoltaic Modules on Pitched Rooftops: A Case of Low Latitude Equatorial Region. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliari, L.; Cocco, D.; Petrollese, M. Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) Deployed for Photovoltaic Curtailment Mitigation. Energies 2025, 18, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Pan, Z.; Huang, H.; Wu, H. Energy Optimization of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic for Load Shifting and Grid Robustness in High-Rise Buildings Based on Optimum Planned Grid Output. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 324, 119320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Sun, Q.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Lin, W. Operation Optimization Strategy of a BIPV-Battery Storage Hybrid System. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cao, S.; Kosonen, R.; Hamdy, M. Multi-Objective Optimisation of an Interactive Buildings-Vehicles Energy Sharing Network with High Energy Flexibility Using the Pareto Archive NSGA-II Algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 218, 113017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ouyang, S.; Sang, H. Decision on Annual Development and Construction Plan for Large-Scale Roof Top Photovoltaic Access to Distribution Network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 245, 111597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Wang, Y. A Distributed Renewable Power System with Hydrogen Generation and Storage for an Island. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 122500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Keubeng, I.G.; Kemezang, V.C. Climate Mitigation Technology for Holistic Resource Management in Sub-Saharan Africa: Impact on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Energy Clim. Change 2024, 5, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paini, A.; Romei, S.; Stefanini, R.; Vignali, G. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Ohmic and Conventional Heating for Fruit and Vegetable Products: The Role of the Mix of Energy Sources. J. Food Eng. 2023, 350, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; Marmiroli, B.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Electricity Production in Italy: Current Scenario and Future Developments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troy, S.; Schreiber, A.; Reppert, T.; Gehrke, H.-G.; Finsterbusch, M.; Uhlenbruck, S.; Stenzel, P. Life Cycle Assessment and Resource Analysis of All-Solid-State Batteries. Appl. Energy 2016, 169, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlschlager, D.; Kigle, S.; Schindler, V.; Neitz-Regett, A.; Fröhling, M. Environmental Effects of Vehicle-to-Grid Charging in Future Energy Systems—A Prospective Life Cycle Assessment. Appl. Energy 2024, 370, 123618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Pechancová, V.; Saha, N.; Pavelková, D.; Saha, N.; Motiei, M.; Jamatia, T.; Chaudhuri, M.; Ivanichenko, A.; Venher, M.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Based Batteries: Review of Sustainability Dimensions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 206, 114860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Lima, L.; Quartier, M.; Buchmayr, A.; Sanjuan-Delmás, D.; Laget, H.; Corbisier, D.; Mertens, J.; Dewulf, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion Batteries and Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries-Based Renewable Energy Storage Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 46, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudhistira, R.; Khatiwada, D.; Sanchez, F. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion and Lead-Acid Batteries for Grid Energy Storage. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, M.F.; Satpathy, P.R.; Prasankumar, T.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Mansor, M.; Walker, S.L. Second-Life Battery Energy Storage System for Energy Sustainability: Recent Advancements, Key Takeaways and Future Perspectives. J. Energy Storage 2025, 123, 116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, A.; Leybros, A.; Doucet, O.; Ruiz, J.-C.; Fontaine-Giraud, P.; Liotaud, L.; Grandjean, A. Versatility Assessment of Supercritical CO2 Delamination for Photovoltaic Modules with Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate, Polyolefin or Ethylene Methacrylic Acid Ionomer as Encapsulating Polymer. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 410, 137292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, C.; Petit, Y.; Karaman, T.; Jahrsengene, G.; Martinez, A.M.; Benayad, A.; Billy, E. Circular Recycling Concept for Silver Recovery from Photovoltaic Cells in Ethaline Deep Eutectic Solvent. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 29174–29183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandra, V.; Sannino, L.; Andreozzi, C.; Flaminio, G.; Pellegrino, M. New PV Encapsulants: Assessment of Change in Optical and Thermal Properties and Chemical Degradation after UV Aging. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 220, 110643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvagno, A.; Prestipino, M.; Maisano, S.; Urbani, F.; Chiodo, V. Integration into a Citrus Juice Factory of Air-Steam Gasification and CHP System: Energy Sustainability Assessment. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 193, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, D.; Prencipe, S.; Ruggeri, M.; Spizzirri, U. Sustainability Assessment of Different Extra Virgin Olive Oil Extraction Methods through a Life Cycle Thinking Approach: Challenges and Opportunities in the Elaio-Technical Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Joumri, L.; Labjar, N.; Dalimi, M.; Harti, S.; Dhiba, D.; El Messaoudi, N.; Bonnefille, S.; El Hajjaji, S. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in the Olive Oil Value Chain: A Descriptive Review. Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapa, M.; Ciano, S. A Review on Life Cycle Assessment of the Olive Oil Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinardi, G.; D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Ingrao, C. Accounting for Circular Economy Principles in Life Cycle Assessments of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Supply Chains—Findings from a Systematic Literature Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 173977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattara, C.; Salomone, R.; Cichelli, A. Carbon Footprint of Extra Virgin Olive Oil: A Comparative and Driver Analysis of Different Production Processes in Centre Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Puig, R.; Martí, E.; Bala, A.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Tackling the Relevance of Packaging in Life Cycle Assessment of Virgin Olive Oil and the Environmental Consequences of Regulation. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, S.; Barbanera, M.; Lascaro, E. Assessment of Carbon Footprint and Energy Performance of the Extra Virgin Olive Oil Chain in Umbria, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482–483, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffia, A.; Palese, A.M.; Pergola, M.; Altieri, G.; Celano, G. The Olive-Oil Chain of Salerno Province (Southern Italy): A Life Cycle Sustainability Framework. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PVGIS Web Application, 2019, Version 5.3 Released. European Commission, Joint Research Centre. 2019. Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Guillén-Lambea, S.; Sierra-Pérez, J.; García-Pérez, S.; Montealegre, A.L.; Monzón-Chavarrías, M. Energy Self-Sufficiency Urban Module (ESSUM): GIS-LCA-Based Multi-Criteria Methodology to Analyze the Urban Potential of Solar Energy Generation and Its Environmental Implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlFaraj, J.; Popovici, E.; Leahy, P. Solar Irradiance Database Comparison for PV System Design: A Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoima, K.N.; Efughu, D.; Azubuike, O.C.; Akpiri, B.F. Investigating the Optimal Photovoltaic (PV) Tilt Angle Using the Photovoltaic Geographic Information System (PVGIS). Niger. J. Technol. 2024, 43, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiman, D. Assessing the Outdoor Operating Temperature of Photovoltaic Modules. Prog. Photovolt. 2008, 16, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld, T.; Friesen, G.; Skoczek, A.; Kenny, R.P.; Sample, T.; Field, M.; Dunlop, E.D. A Power-Rating Model for Crystalline Silicon PV Modules. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 3359–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehl, M.; Heck, M.; Wiesmeier, S.; Wirth, J. Modeling of the Nominal Operating Cell Temperature Based on Outdoor Weathering. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Ruiz, J.M. Calculation of the PV Modules Angular Losses under Field Conditions by Means of an Analytical Model. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2001, 70, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.; Schalbart, P.; Assoumou, E.; Peuportier, B. Integrating Climate Change and Energy Mix Scenarios in LCA of Buildings and Districts. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Heath, G.; Raugei, M.; Sinha, P.; de Wild-Scholten, M. Methodology Guidelines on Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Electricity, 2nd ed.; IEA PVPS Task 12, Report IEA-PVPS T12-06:2016; International Energy Agency Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme: Paris, France, 2011; ISBN 978-3-906042-38-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin, R.; Nabi, M.N.; Rashid, F.; Hossain, M.A. Solar, Wind, Hydrogen, and Bioenergy-Based Hybrid System for Off-Grid Remote Locations: Techno-Economic and Environmental Analysis. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Imagery. ArcGIS Website. 2025. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=6299481745644df6a7b2808bfcce7f96 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Koh, S.C.L.; Vigiano, A. Lighting the Future of Sustainable Cities with Energy Communities: An Economic Analysis for Incentive Policy. Cities 2024, 147, 104828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Monge, M.; Zalba, B.; Casas, R.; Cano, E.; Guillén-Lambea, S.; López-Mesa, B.; Martínez, I. Is IoT Monitoring Key to Improve Building Energy Efficiency? Case Study of a Smart Campus in Spain. Energy Build. 2023, 285, 112882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinardi, G.; D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Muradin, M.; Ingrao, C. A Systematic Literature Review of Environmental Assessments of Citrus Processing Systems, with a Focus on the Drying Phase. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 974, 179219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.A.; Ali, A.A.; Swief, R.A.; Elazab, R. Optimizing Energy-Efficient Grid Performance: Integrating Electric Vehicles, DSTATCOM, and Renewable Sources Using the Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaier, A.A.; Elymany, M.M.; Enany, M.A.; Elsonbaty, N.A. Multi-Objective Optimization and Algorithmic Evaluation for EMS in a HRES Integrating PV, Wind, and Backup Storage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malode, S.; Prakash, R.; Mohanta, J.C. Sustainability Assessment of Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Systems: A Case Study. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 108, 107609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiong, R.; Meng, X.; Deng, X.; Li, H.; Sun, F. Battery Degradation Evaluation Based on Impedance Spectra Using a Limited Number of Voltage-Capacity Curves. eTransportation 2024, 22, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, D.; Carbone, R.; Pulvirenti, A.; Rizzo, M.; D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G. What Gets Measured Gets Managed-Circular Economy Indicators for the Valorization of By-Products in the Olive Oil Supply Chain: A Systematic Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Case1 | Case2 | Case3 | Case4 | Case5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Technology | Pressure | Decanter (2 phases) | Decanter (3 phases) | Decanter (3 phases) | Decanter (3 phases) |

| Olive milled (q/y) | 4500 | 5700 | 12,000 | 9000 | 7000 |

| Olive yield (kg/ha) | 6125 | 7180 | 7092 | 6871 | 5956 |

| Oil yield (L/ha) | 1120.91 | 1345.27 | 1282.43 | 1264.92 | 1025.10 |

| Cultivation surface (ha) | 120 | 150 | 270 | 240 | 190 |

| Localisation | Ortona (CH) * | Moscufo (PE) ** | Pianella (PE) ** | Pianella (PE) ** | Casoli (CH) * |

| Primary Packaging | Glass bottle | Steel can | Glass bottle | Glass bottle | Glass bottle |

| Secondary Packaging | Cardboard | Cardboard | Cardboard | Cardboard | Cardboard |

| Variable | Type | Description | Unit | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | Integer | Current month | - | 1 to 12 |

| g | Integer | Current day | - | 1 to 31 |

| h | Integer | Current hour | - | 0 to 23 |

| EPV | Double | PV Energy produced and self-consumed by olive mill | kWh | obtained by energy simulations |

| EB | Double | PV Energy stored by BESS and self-consumed by olive mill | kWh | obtained by energy simulations |

| ER | Double | Sum of EPV and EB | kWh | obtained by energy simulations |

| ENG | Double | Electric energy requested by NG | kWh | obtained by energy simulations |

| EOut | Double | Energy delivered to the NG | kWh | obtained by energy simulations |

| acc | Double | Counter state of charge | kWh | 0 to CBESS |

| CBESS | Double | Maximum battery capacity | kWh | obtained by energy simulations |

| Ep(m, h) | Double | Hourly energy produced by PV | kWh | (1 To 12, 0 To 23) |

| Ec(m, h) | Double | Hourly energy requested by the olive mill | kWh | (1 To 12, 0 To 23) |

| g_m(m) | Integer | g_m days in a month | days | (1 To 12) |

| Case | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Ec | kWh y−1 | 29,651.4 | 21,537.45 | 48,099.6 | 46,033.2 | 34,729.8 | |||

| Milled olives | t y−1 | 450 | 570 | 1200 | 900 | 700 | |||

| oil yield | L ton−1 | 183.01 | 187.36 | 180.83 | 184.10 | 172.11 | |||

| Ec/hourly | kWh h−1 | 64.6 | 21.1 | 47.2 | 45.1 | 34.0 | |||

| Activity hours | 8 a.m–8 p.m | ||||||||

| Rooftop available area (azimuth) | m2 | 82 (0) | 196 (−95) | 457 (85) | 550 (opt) | 155 (−22) | 124 (18) | 202 (18) | 202 (162) |

| Rooftop: flat (pitch)/slope (tilt angle) | - | Slope (30°) | Slope (20°) | Slope (15°) | Flat (2.7 m) | Slope (20°) | Slope (30°) | Slope (5°) | Slope (5°) |

| N° panels | n | 36 | 96 | 216 | 83 | 61 | 56 | 98 | 98 |

| PV peak power | kWp | 15.48 | 41.28 | 92.88 | 35.69 | 26.23 | 24.08 | 42.14 | 42.14 |

| Occupied area | m2 | 72 | 192 | 432 | 166 | 122 | 112 | 196 | 196 |

| Yearly PV prod. | kWh y−1 | 20,600.17 | 152,620.83 | 46,602.53 | 35,831.34 | 117,034.38 | |||

| Process | Input | Unit | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| olive oil extraction | Water | L | 15 | 17 | 119 | 127 | 100 |

| Synthetic rubber | kg | 1.212 | 1.861 | 2.533 | 0.587 | 1.921 | |

| Stainless steel | kg | 3.667 | 2.732 | 0.943 | 0.482 | 1.543 | |

| packaging | Greenglass | kg | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.108 |

| Aluminium cap | kg | 0.770 | 0.000 | 0.770 | 0.770 | 0.770 | |

| Non-drip spout | kg | 0.157 | 0.000 | 0.157 | 0.157 | 0.157 | |

| Front Cardboard label | kg | 0.218 | 0.000 | 0.218 | 0.218 | 0.218 | |

| Rear Cardboard label | kg | 0.162 | 0.000 | 0.126 | 0.144 | 0.144 | |

| Shrink cap | kg | 1.264 | 0.000 | 0.126 | 0.126 | 0.126 | |

| Steel can | kg | 0.000 | 18.722 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Cardboard Can label | kg | 0.000 | 0.396 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Can plastic cap (LDPE) | kg | 0.000 | 0.092 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Corrugated cardboard box | kg | 11.376 | 24.127 | 10.951 | 11.462 | 11.738 | |

| Adhesive tape (LDPE Glue) | kg | 0.045 | 0.648 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.045 | |

| LLDPE film | kg | 0.324 | 0.185 | 0.356 | 0.332 | 0.345 | |

| Pallet | kg | 5.987 | 3.318 | 6.134 | 6.211 | 6.067 | |

| transport of materials | Input transport to the mill | tkm | 1.456 | 2.027 | 1.323 | 1.894 | 2.234 |

| electricity in the baseline scenario | kWh | 65.892 | 37.785 | 40.083 | 51.148 | 49.614 | |

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPV | SPV+BESS | SPV | SPV+BESS | SPV | SPV+BESS | SPV | SPV+BESS | SPV | SPV+BESS | ||

| CBESS | kWh | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 80 | 0 | 10.0 | 0 | 12.5 | 0 | 90 |

| EPV | kWh | 3249.8 | 3249.8 | 13,160.4 | 13,160.4 | 8124.5 | 8124.5 | 5509.4 | 5509.4 | 15,295.15 | 15,917.14 |

| ENG | kWh | 26,401.6 | 26,139.2 | 8377.1 | 3293.9 | 39,975.1 | 39,686.4 | 40,523.8 | 39,955.9 | 19,434.65 | 16,257.79 |

| EOut,tot | kWh | 17,319.8 | 17,034.8 | 139,294.9 | 133,334.0 | 38,402.1 | 38,095.9 | 30,268.9 | 29,701.1 | 93,729.59 | 98,433.59 |

| EOut,act | kWh | 285.1 | 0.0 | 9642.7 | 3681.8 | 306.2 | 0.0 | 586.0 | 18.2 | 2038.93 | 0 |

| EB | kWh | 0.0 | 262.4 | 0.0 | 5083.3 | 0.0 | 288.8 | 0.0 | 567.9 | 0 | 2554.87 |

| ER | kWh | 3249.84 | 3512.23 | 13,160.35 | 18,243.60 | 8124.5 | 8413.2 | 5509.4 | 6077.3 | 15,295.15 | 18,472.01 |

| Self-consuming | 15.8% | 17.1% | 8.6% | 12.0% | 17.4% | 18.1% | 15.4% | 17.0% | 12.5% | 13.1% | |

| CEN | % | 11% | 11.9% | 61.1% | 84.7% | 16.9% | 17.5% | 12.0% | 13.2% | 44.0% | 53.2% |

| Scenarios | Input | Unit | Case1 | Case2 | Case3 | Case4 | Case5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNG | ENG | kWh/ton | 65.892 | 37.785 | 40.083 | 51.148 | 49.614 |

| SPV | ENG | kWh/ton | 58.670 | 14.697 | 33.31 | 45.03 | 26.86 |

| ER | kWh/ton | 7.222 | 23.088 | 6.77 | 6.12 | 22.74 | |

| EOut,tot | kWh/ton | 38.49 | 244.377 | 32.002 | 33.63 | 144.27 | |

| SPV+B | ENG | kWh/ton | 58.032 | 5.779 | 33.07 | 44.40 | 15.57 |

| ER | kWh/ton | 7.855 | 32.006 | 7.01 | 6.75 | 34.04 | |

| EOut,tot | kWh/ton | 37.86 | 233.919 | 31.761 | 33.00 | 170.87 | |

| WB | kgB/ton | 0.0190 | 0.120 | 0.0073 | 0.0120 | 0.113 |

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPV | SPV+B | SPV | SPV+B | SPV | SPV+B | SPV | SPV+B | SPV | SPV+B | ||

| Initial cost | €/y | 18,576.0 | 21,576.0 | 160,992.0 | 208,992.0 | 42,828.0 | 48,828.0 | 31,476.0 | 38,976.0 | 130,032.0 | 184,032.0 |

| Avoided costs | €/y | 650.0 | 702.4 | 2632.1 | 3648.7 | 1624.9 | 1682.6 | 1101.9 | 1215.5 | 3059.0 | 3694.4 |

| Annual gain | €/y | 1385.6 | 1362.8 | 11,143.6 | 10,666.7 | 3072.2 | 3047.7 | 2421.5 | 2376.1 | 7498.4 | 7874.7 |

| O&M | €/y | 185.8 | 431.5 | 1609.9 | 4179.8 | 428.3 | 976.6 | 314.8 | 779.5 | 1300.3 | 3680.6 |

| Annual benefit | €/y | 1849.8 | 1633.7 | 12,165.7 | 10,135.6 | 4268.8 | 3753.8 | 3208.6 | 2812.0 | 9257.1 | 7888.4 |

| PBT | y | 10.0 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 20.6 | 10.0 | 13.0 | 9.8 | 13.9 | 14.0 | 23.3 |

| PBT (−80%) | y | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 4.7 |

| PBT (−50%) | y | 5.0 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 10.3 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 4.9 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 11.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cinardi, G.; D'Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C. Integrating Rooftop Grid-Connected Photovoltaic and Battery Systems to Reduce Environmental Impacts in Agro-Industrial Activities with a Focus on Extra Virgin Olive Oil Production. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040091

Cinardi G, D'Urso PR, Arcidiacono C. Integrating Rooftop Grid-Connected Photovoltaic and Battery Systems to Reduce Environmental Impacts in Agro-Industrial Activities with a Focus on Extra Virgin Olive Oil Production. Clean Technologies. 2025; 7(4):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040091

Chicago/Turabian StyleCinardi, Grazia, Provvidenza Rita D'Urso, and Claudia Arcidiacono. 2025. "Integrating Rooftop Grid-Connected Photovoltaic and Battery Systems to Reduce Environmental Impacts in Agro-Industrial Activities with a Focus on Extra Virgin Olive Oil Production" Clean Technologies 7, no. 4: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040091

APA StyleCinardi, G., D'Urso, P. R., & Arcidiacono, C. (2025). Integrating Rooftop Grid-Connected Photovoltaic and Battery Systems to Reduce Environmental Impacts in Agro-Industrial Activities with a Focus on Extra Virgin Olive Oil Production. Clean Technologies, 7(4), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040091