1. Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO

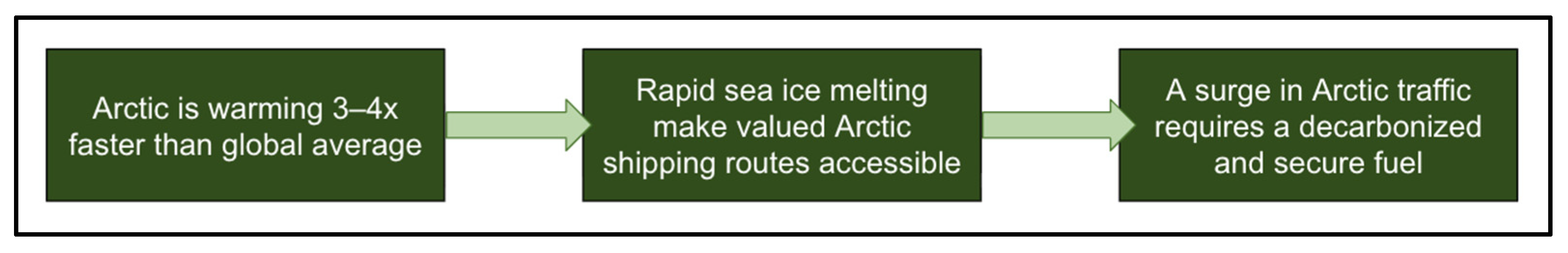

2) and other greenhouse gases (GHG) are being emitted at unprecedented levels in human history. For Alaska, the situation is delicate as the Arctic is warming three to four times faster than the global average [

1]. Arctic and subarctic ecosystems and communities face rapidly melting sea ice, thawing permafrost, extreme weather, and a feedback loop of accelerated global warming [

2,

3]. This environmental shift greatly influences local people, such as the catastrophic flood in Kipnuk in October 2025 that displaced over 1500 people [

4]. However, this also holds global implications for geopolitics, energy demands, and the maritime shipping industry.

Climate projection models predict the Arctic shipping season lengthening seven days per decade, which would lead to ice-free Arctic water as early as 2035 [

5,

6]. A 37% jump in Arctic maritime traffic from 2013 to 2023 has already been detected alongside an 82% increase in fuel use since 2016 [

7]. These Arctic routes offer large economic advantages compared to traditional routes, saving 14–20 days between ports in northwest Europe and northeast Asia at sea and reducing emissions by 24% due to less time at sea [

3,

6]. These alternatives would reduce reliance on one route which can cause supply chain delays, increase consumer expenses, and jeopardize food security [

8]. The three main routes, as mapped in

Figure A1, include the Northern Sea Route (NSR), the Northwest Passage (NWP), and the future Transpolar Route (TPR). For Alaska, increased maritime traffic is a major concern, from national security, tourism, to subsistence activities as seen in

Figure A2 [

5].

Alaska’s energy landscape is unique due to its low population density, high energy demand, harsh climate, and reliance on fossil fuels. Despite being an oil-producing state, Alaska’s crude oil is mostly refined elsewhere, leading to high prices for imported diesel. Alaska has the potential for a very diverse energy portfolio, including all types of renewable energy, such as extensive geothermal resources. In 2024, the state reached 30% renewable electricity, mainly from hydropower [

9]. However, only 8.6% of the state’s total energy consumption goes toward electricity generation, so decarbonization of Alaska’s non-electric sectors is necessary [

9].

Power-to-X (PtX) converts electricity into energy products known as X. This starts with water electrolysis, splitting into hydrogen and oxygen [

10,

11,

12]. When that electricity comes from a renewable source, the end product is called “green hydrogen”. Thus, geothermally powered PtX is Geothermal-to-X (GtX). Hydrogen will be a crucial part of decarbonization as it can turn electricity into a storable product, which is key for grid stability. As the first product, hydrogen can be used directly as a fuel, blended with fossil fuels, or converted into other X products [

12]. Renewable-energy-powered PtX, from electricity generation to hydrogen production, emits no GHGs. This distinguishes it from fossil-fuel-based PtX, as over 95% of commercial hydrogen comes from nonrenewable sources and it costs 3–4 times less than green hydrogen [

10,

12].

Unlike intermittent renewables, such as solar or wind, geothermal provides reliable power year-round with a capacity factor of 80–90%, which is higher than nearly every other energy type [

11,

13,

14]. This consistency makes geothermal power similar to fossil fuels; however, geothermal produces very low GHG emissions and requires minimal land use, making it unique [

13,

15]. As a domestic resource, it offers a path to energy security. The Russia–Ukraine conflict has highlighted how energy and geopolitical stability are linked. Europe faced a rapid reduction in reliance on importing Russian natural gas from 40% in 2021 to just 11% by 2024 [

16]. Fossil fuels supply 80% of the world’s energy despite progress toward renewable horizons [

16]. Renewable energy offers more than just environmental merits; it offers energy independence by providing a diverse, local, and stable energy portfolio by not having to rely on foreign countries and supply chains. This paper will investigate the ability to use Alaska’s abundant geothermal resources for GtX. It is critical to address the need to decarbonize shipping in Alaska to mitigate the Arctic’s accelerated warming and its global consequences, while not removing secure and scalable fuels.

2. Materials and Methods

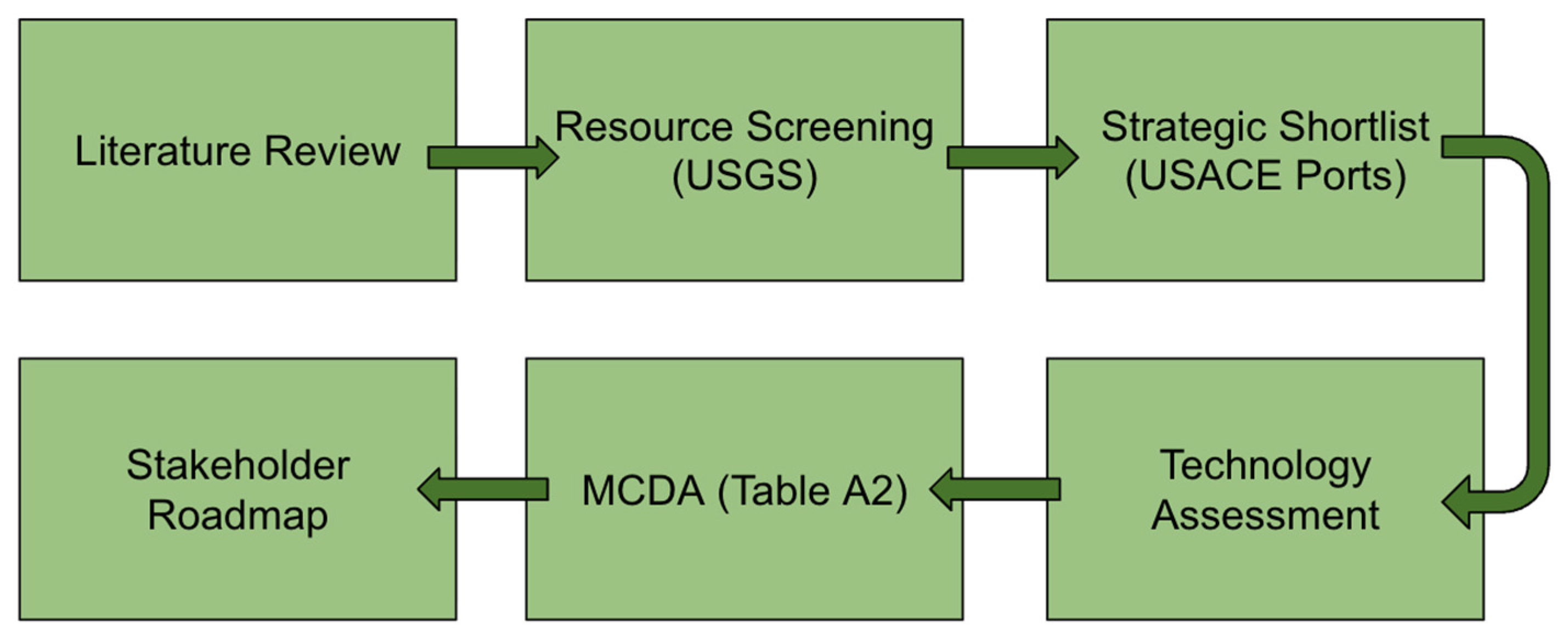

This study is a feasibility assessment of GtX for sustainable maritime refueling in Alaska fit to address the lack of literature reviewing GtX processes, specifically none in off-grid conditions. The methodology combines four key perspectives: technical, economic, strategic, and geological.

Figure A3 displays this methodology, visualizing a multi-faceted preliminary assessment of a new technology in unique and urgent conditions.

The technical assessment focuses on PtX technologies, particularly green hydrogen and its derivatives, as well as various GtX methods, including conventional electrolysis from geothermal electricity, high-temperature steam electrolysis (HTSE), waste heat utilization, and the potential use of hydrogen sulfide and CO2 emissions.

The economic assessment relies on publicly available data on Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) and Levelized Avoided Cost of Electricity (LACE), as defined in

Figure A4, for different generation technologies and projected costs for PtX products, including Levelized Cost of Hydrogen. Data is primarily sourced from multilateral organizations such as Lazard, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). This assessment incorporates the unique economic benefits of geothermal.

The strategic assessment evaluates the strategic importance of key Alaskan locations based on their proximity to Arctic shipping routes, resource extraction sites, existing port infrastructure, and geopolitical context. Locations of interest were synthesized from reports such as the United States Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) Alaska Deep-Draft Arctic Port System study.

The geological assessment uses data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and scientific reports to identify high-potential geothermal resources, with a focus on the Aleutian Volcanic Arc. From the shortlist from USACE, this study explored the location’s geothermal potential. Case studies for Adak Island, Unalaska, Akutan, Nome, and Augustine Island were selected based on resource quality, strategic advantage, and existing infrastructure. These locations are mapped in

Figure A1.

In order to quantify this feasibility assessment, a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) framework was used to provide a ranking of locations of interest. This approach integrates findings from the economic, strategic, and geological perspectives into a systematic comparison of the case study sites selected. The technical assessment was excluded from the MCDA, as it is not site specific, but was conducted to investigate a broader trend towards affordable electrolyzers. For the MCDA, criteria were selected based on the literature review, evaluating key factors for GtX implementation in a remote Arctic community. Criteria chosen includes Geothermal Resource Quality, energy demand, accessibility, and infrastructure.

Geothermal Resource Quality is not just based on resource temperature, but for a preliminary study with limited data, it is a good proxy to warrant future investigation. Ideally, a full assessment would consider other important variables such as permeability, depth-to-target reservoir, and presence of fluid. However, newer technology types, such as Enhanced Geothermal Systems, can still be utilized. For energy demand, three components were considered: the number of electricity customers for each location, the tonnage of cargo that passes through each port per year, and the commercial cost of electricity. A high tonnage of cargo moving within a port indicates a high demand for fuel at that site. The average energy price was calculated by (MWh

Residential × USD/kWh

Residential) + (MWh

Commercial × USD/kWh

Commercial)/(MWh

Residential + MWh

Commercial). This study does not include site-specific Levelized Cost of Hydrogen calculations, due to a lack of available data, such as high-resolution geothermal reservoir characteristics, local grid dynamics, and site-specific cost adders. This is designated as a good next step in the

Section 4.3 and

Table A5. Accessibility and Infrastructure are determined by how long each port is operable per year due to ice, if there is road access, and the port type. Sea ice through the Arctic routes is predicted to become operable year-round in the future, but having current year-round ice-free ports is essential to start addressing a demand for X products. Port type serves a similar function, as a deep draft port is necessary for the presence of large cargo ships that will use the NSR, NWP, and future TPR for a less-expensive shipping route. It is important to note that for Augustine Island, which is uninhabited but included in this study due to its proximity to the Railbelt Grid, Anchorage’s portion of the Railbelt Grid is used as a proxy for the Energy Demand section. This reflects the potential scale of market access, as a GtX hub would be suited for grid accessibility and exports rather than local needs. Adak and Akutan were given a tied score of 2 for Cargo Tonnage as their tonnage data was not publicly available, and this score sought to reflect their status as smaller, remote, fishing ports.

An equal weighting is applied to all criteria to ensure that the assessment is unbiased, reflecting the idea that no single barrier is considered insurmountable without knowing more from a detailed site-specific study. This provides a full scope to compare each location. Each location was ranked 1–5 in

Table A3 for each criteria, with 5 being most advantageous and 1 being least.

Table A2 provides the publicly available data and further context that

Table A3 is based off of. A total score at the bottom of

Table A3 provides a transparent and quantitative ranking that informs the study’s final recommendation and a roadmap for stakeholders (

Table A4).

The report also incorporates the impact of stakeholder engagement, specifically the importance of a Social License to Operate (SLO). Policy frameworks were reviewed to understand the influence on cost, risk, and timeline. The assessment explores how US energy policy is evolving, specifically how initiatives affect GtX. Together, these perspectives form a comprehensive picture of where GtX technology for sustainable maritime refueling and community use is feasible.

3. Results

This section presents the key findings from the feasibility assessment, covering the technical, economic, strategic, and geological applications of GtX in Alaska. There are several methods to involve geothermal energy in PtX processes, including low- and high-temperature resources. Given the geographic specifications of each geothermal resource, this is an advantage of geothermal energy for more widespread use.

Water Electrolysis from Geothermal Electricity is the most established and commercially available method. For GtX, heat is converted into mechanical work to generate electricity, which powers electrolysis. Geothermal power plants with multiple flash stages are best suited for hydrogen production [

17]. Electrolysis is most efficient at high temperatures, making geothermal a good choice [

18]. This stable, round-the-clock power ensures continuous operation of the electrolyzer, maximizing efficiency and output.

Thermal Energy and Waste Heat Utilization uses excess and waste heat of geothermal plants. An advantage of geothermal rather than other energy for green hydrogen production is the liquid’s thermal capacity to pre-heat water for electrolysis or cool for liquefaction [

19,

20]. Low-temperature water heating pre-electrolysis saw increases in system efficiency up to 52% over a non-preheated system [

17].

High-Temperature Steam Electrolysis (HTSE), a relatively new technology, uses Solid Oxide Electrolysis to split water vapor at high temperatures (850–900 °C) using a series of heat exchangers [

17]. Geothermal resources can be integrated through a dual-feed scheme, providing both electricity to drive electrolysis and heat to preheat water and convert to steam needed for this process. Higher geothermal fluid temperatures directly increase hydrogen output and efficiency [

19]. Given thermal energy’s use in the process, less electricity energy is needed, potentially lessening the cost of production [

17].

Emissions Utilization of H

2S and CO

2 are typically emitted from conventional geothermal plants and can be the input for GtX, turning waste into a valuable resource [

17,

21]. H

2S can be used for electrolysis, and CO

2 can be a sustainable carbon source for hydrogen-to-methanol.

Geothermal Heat in Thermochemical Processes use high temperatures to drive a thermochemical process to produce hydrogen at a lower temperature. The copper–chlorine cycle is the most promising for GtX due to its efficiency and a temperature range of 350–530 °C rather than direct water electrolysis, which tends to be between 850 and 900 °C [

17,

20]. The lower temperatures of conventional steam, around ~250 °C, can be applied to reduce the heat requirement.

As illustrated in

Figure A5, geothermal energy’s versatile nature allows it to power PtX processes in diverse ways, enabling both low- and high-temperature resources to contribute to the production of green fuels. This adaptability is a significant strength when considering the varied geothermal potential across Alaska.

3.1. Economic Competitiveness

The feasibility of GtX to supply Alaska’s maritime refueling industry relies on understanding its cost, from product generation to infrastructure needed.

The economic viability of green hydrogen, the primary product of PtX, is dependent on the price of renewable electricity and electrolyzers. When compared to current shipping fuels, its high cost of 3–6 USD/kg is the main barrier to its development [

22]. Widespread adoption would require industrial prices less than 5 USD/kg and residential or commercial prices under 2 USD/kg [

23]. Electrolyzer Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) is projected to fall from 1429 USD/kW H

2 in 2021 to 600 USD/kW H

2 by 2050 as electrolyzer costs fall [

24]. Cost varies between different types of electrolyzers, with proton exchange membrane electrolysis (PEM) estimated at 4.45–6.05 USD/kg and alkaline electrolysis at 4.33–5.49 USD/kg. Tax subsidies decrease this even further at respective costs of 2.48–4.08 USD/kg and 2.36–3.52 USD/kg [

25]. Projections show that PEM electrolyzers, which are better suited for large-scale production, will become competitive as both technologies could drop below 1.75 USD/kg [

22].

Producing green hydrogen from geothermal systems has shown costs between 0.97–8.24 USD/kg, which is lower than average from solar- and wind-derived hydrogen at 2.88–20.5 USD/kg [

17]. The range in pricing comes from a variety of geothermal technologies, from varied reservoir quality and management, as well as GtX being a new technology. High-temperature resources, such as the Aleutian Volcanic Arc explained in the

Section 3.3, would likely fall on the lower end of this range given their high geothermal resource temperatures, allowing for more efficient power or e-fuel conversion. Binary geothermal plants are estimated as low as 2.37 USD/kg, with the potential to drop to 1.088 USD/kg with alkaline electrolyzers [

20]. Further reductions are possible through hybrid power systems, combining geothermal energy’s steady baseload with a regionally low-cost secondary renewable resource [

11].

Despite high upfront costs, geothermal energy is cost-competitive with other resources due to its baseload and dispatchable nature.

Table A1 and

Figure A6 compare the LCOE across sources. LCOE does not take into account system-wide costs such as the need for backup diesel, adding grid connections, or large amounts of battery storage [

11,

15], all factors that geothermal energy does not require whereas intermittent renewables do. For remote Alaskan locations, particularly for isolated or islanded microgrids, geothermal energy offers grid stability. Its continuous, 24/7 baseload output means it does not need to rely on backup diesel. For implementation in existing grids, this is an advantage as fewer grid upgrades are necessary. The average LCOE from 2016 to 2023 across all geothermal technologies was 71 USD/MWh [

13]. Lazard’s 2024 study further highlights this, showing a 38.55% decrease in geothermal LCOE from 2009 to 2024 [

25]. Given the significance of electricity generation cost in PtX pricing, geothermal energy’s cost comparison, even with nonrenewable resources, is strong. Geothermal energy was the only energy type with a positive difference between LCOE and LACE and an average value–cost ratio greater than one, confirming that its reliability outweighs its high upfront costs [

14,

15]. Between new advancements in drilling techniques and the availability of subsidies, the cost of geothermal exploration will likely decrease even more.

Still, in GtX applications for the maritime industry, converting hydrogen into more transportable fuels such as methane, methanol, or ammonia is the best path forward with steep projected price drops [

24]. However, Alaska’s unique geographical conditions present challenges despite this promising trend. High-potential geothermal areas, often associated with strategic port locations like the Aleutians, tend to be remote and sparsely populated [

26,

27]. Developing a functional GtX supply chain requires coordination across multiple critical infrastructure sectors:

Port Upgrades: Deepwater ports are necessary to host large vessels, from cargo to military to cruise ships, that are increasingly heading north. Upgrading from a shallow to a deepwater port is expensive. Maintenance of deepwater ports through dredging expenses and storm repairs must be taken into account.

Storage Facilities: To accommodate the transport and storage of low-temperature or pressurized fuel, such as hydrogen or ammonia, will require significant investment.

Regulations: High-level safety systems are needed to safely handle fuels. Alaska, being an active seismic zone, requires further safety protocols.

Supply Chain and Logistics: Remote location, harsh weather, short windows of warm weather, and reliance on barge or air from the Lower 48 adds to costs and limits construction [

5,

28].

Workforce Infrastructure: Providing housing for staff will be necessary. Training a local workforce will be beneficial, but many remote communities are extremely low-population island communities and will likely require outside staff.

These sectors will require investments not taken into account by LCOE estimates but which are essential within a remote Arctic location. Furthermore, co-generation opportunities can significantly offset production costs. For example, oxygen, a byproduct of electrolyzers, can be sold for industrial use, and excess heat can be used for residential or commercial uses [

23]. The use of direct heat for greenhouses will be a large asset for Alaskan communities, contributing to food security in areas that ship in the majority of food [

27].

3.2. Strategic

The strategic importance of Alaska’s maritime geography is increasing due to the warming Arctic. The NWP offers transit time considerably shorter than the Panama Canal, connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans along the coasts of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Infrastructure along this route is sparse as it has been historically covered in ice for the majority of the year. The US has several deepwater ports along Alaska’s southern coast, leaving the northern coast severely limited for Arctic access [

29]. These waterways are crucially positioned between superpowers, US and Russia, and have the potential to be a military and trade stronghold between North American and Indo-Pacific regions. Further, the Arctic holds significant resources, including 10–15% of the world’s oil and gas supply [

30]. For Alaska, its natural resources are a cornerstone of its economy. The oil and gas industry is highly transferable to geothermal energy, meaning that utilizing the crossover of workforce, capital, and political backing is crucial. The vast potential of geothermal energy, combined with a warming Arctic and increasing maritime traffic, makes GtX a strategic and sustainable solution for Alaska.

Table A2’s Infrastructure and Accessibility section denotes specific values for the five case study sites. Variables include ice-free harbors (year-round or seasonal access), transportation type access (air, coastal, etc.), port type (deepwater, shallow, or none), and the presence of existing military infrastructure. These factors help develop a picture of how feasible introducing a new GtX hub at that location would be. The ideal case would be a year-round ice-free deepwater port with transportation infrastructure such as road access, an airport, and a dock.

3.3. Geological Case Studies

Alaska’s extensive geothermal potential is estimated at 677 MW of electrical power generation [

30]. A flaw of geothermal energy is that it is extremely geographically constrained; however, Alaska is one of only eight US states to currently generate geothermal electricity, albeit much beneath the capacity [

9]. Between its unique geology and strategic location, Alaska is a promising opportunity for GtX projects.

The state’s geothermal zones can be arranged in four main areas: Aleutian Volcanic Arc, Central Alaska Hot Springs Belt (CAHSB), Wrangell Mountains, and the Southeast Panhandle. The CAHSB and Southeast Panhandle are noted by hot springs and low-to-moderate-temperature sporadic resources; the Wrangell Mountains are set inland and include a deeper volcanic resource [

26]. The most attractive area for GtX production is the Aleutian Volcanic Arc, an island system over 2500 km long caused by the subduction of the Pacific Plate under the North American Plate. These islands consist of plutonic and volcanic rocks and are characterized by frequent and intense seismic activity, creating a complex system of faults and folds which increase permeability for geothermal reservoirs [

26]. The Aleutian Islands contain over 57 volcanoes, with at least 14 identified as high-temperature resources, offering a thermal energy potential of at least 7 × 10

22 joules (J) [

26]. The shallow, high-temperature nature of the resources alludes to a higher return on investment for production companies. In addition, the Aleutian Islands provide access to the Indo-Pacific region as well as an entrance to the Bering Strait. Existing ports along this area, which tend to be ice-free year-round, will be better suited to handle the increase in maritime traffic entering the Arctic. However, given the remote and tectonically active nature of the region, geologic hazards and the cost of a lack of existing grid connections or population centers can create limitations.

3.4. Locations of Interest

Adak: As a former US Navy Base from World War II in the Aleutian Islands, Adak Island features the US’s westernmost ice-free deepwater port. This existing infrastructure for energy and maritime transport and proximity to Indo-Pacific trade makes it a strategic hub for refueling not just commercial vessels but also military assets, bolstering energy security and national defense. It is home to a substantial geothermal resource with an estimated thermal energy of 50 × 10

18 J, with recorded temperatures of 150 °C and 239 °C [

26]. With temperatures greater than 150 °C, the reservoir would be suited for direct use, electricity generation, and hydrogen production, which is reflected in its strong score of 4 in Geothermal Resource Quality [

17]. Mount Adagdak, a local volcano, exhibits near-surface potential though its fumaroles, mud pots, hot springs, and hydrothermally altered zones [

26,

31]. Between its geothermal resource, current green ammonia project, existing infrastructure, and strategic export advantages, GtX production on Adak Island is a viable choice.

Unalaska: The Port of Dutch Harbor, located in Unalaska, is a deepwater, ice-free port in the Aleutians and the largest US seafood port by volume, which is reflected in its high score for Cargo Tonnage (4) [

32,

33]. Seafood processing also presents a need for geothermal cooling. This existing maritime infrastructure and strong energy consumption from fishing fleets create a strong case for a GtX facility. The community relies entirely on diesel for electricity and heat, providing economic reasons to pursue renewable energy. Unalaska’s score of 3 in Average Energy Price reflects its 0.41 USD/kg of energy [

34]. Unalaska possesses a large geothermal resource (194 °C) to support 500 MW for 500 years as a source of 25 × 10

18 J [

26]. Plans for a 30 MW geothermal plant are underway with a 50-year lease and permits, with the potential to offset the community’s USD 14.4 million in annual diesel costs [

28]. The community also has a local hydrogen demand of 9900 tons per year, which could grow to 260,000 tons should a trans-Pacific hydrogen network develop [

32]. The City of Unalaska’s commitment to geothermal energy, despite setbacks over the years, solidifies the potential for GtX here.

Akutan: As another fishing hub in the Aleutians, Akutan is home to a major seafood production facility that demonstrates a need for fuel and provides energy infrastructure. This island contains thermal springs, a fumarole field, and one of the most active volcanoes in the country. Its geothermal resource is estimated at 25 × 10

18 J with subsurface reservoir temperatures of 180–190 °C [

26,

31]. A more recent 2012 study suggested that the resource may be 10 times larger than predicted, with a heat output of 29 MW and temperatures of 200–240 °C [

35]. This makes Akutan highly viable for GtX, with potential plans for two 6 MW power plants that could provide a stable, baseload power supply for an electrolyzer.

Nome: Nome, just 230 km south of the Arctic Circle, is located at a unique geographic position. Being disconnected from the Railbelt and at the mouth of the Bering Strait means that Nome is at a chokepoint for trans-Arctic shipping and acts as a regional hub with high diesel prices. There are ongoing plans to expand the Port of Nome into a deep-draft port that will handle larger and higher maritime traffic and require new fuel solutions [

29]. At a distance of 75 km away, Pilgrim Hot Springs is home to a series of pools with temperatures up to 81 °C and host reservoir temperatures of 146–154 °C [

31]. As part of the Central Alaska Hot Springs Belt, this estimated 19 MW of thermal energy is well-suited for direct, local use rather than indirect production of electricity. This contributes to Nome’s lower score (1) for Geothermal Resource Quality compared to other volcanic, high-temperature resources. Still, use of waste heat to lower the temperature barrier for electrolysis is possible. Nome, a diesel-powered microgrid, uses ~1.9 million gallons of fuel every year and could benefit from geothermal energy [

33]. In 2022, the Department of Energy (DOE) awarded Unaatuq Limited Liability Company (LLC) nearly USD 2 million to fund a 65 kW geothermal plant at Pilgrim Hot Springs [

9].

Augustine Island: Augustine Island is located near the Railbelt Grid, Alaska’s largest grid, with over 112,000 customers serviced by Chugach Electric Association [

34]. Adding GtX here would significantly reduce transmission costs for indirect geothermal energy and increase access to a large grid-tied market for transportation fuels. The island has no population base or infrastructure, but nearby demand could offset those costs. Ted Stevens International Airport is the third largest cargo airport in the world, serving as a refuel point for many flights [

9]. GtX offers an opportunity to displace emissions from standard aircraft fuels. Further geophysical exploration of Mount Augustine is underway, indicating serious commercial interest. As of 4 August 2025, GeoAlaska LLC (Anchorage, AK, USA) partnered with Ignis Energy, a startup with interests in geothermal-to-hydrogen technology, in a power purchase agreement with Chugach Electric Association to explore an estimated 200+ MW addition to the Railbelt’s grid [

36].

4. Discussion

The findings of this feasibility assessment establish GtX as a viable and strategically imperative solution for Alaska’s unique energy demands in a rapidly changing Arctic. Geothermal’s stable baseload power, high capacity factor, competitive costs, and relative abundance in Alaska, particularly the Aleutian Islands, make it a solution of interest for the region. Using geothermal energy for Power-to-X products that are storable and applicable for the maritime industry and beyond will make it a fundamental pillar for decarbonization and economic growth.

The biggest implication is GtX’s contribution to national energy security and geopolitical stability. The Aleutian Islands are key chokepoints to Arctic shipping routes, fit with high-quality geothermal resources and ice-free deepwater ports. A GtX hub would provide secure, domestic fuel for commercial and military actions, reducing reliance on global supply chains and foreign fossil fuels. This transition allows the US to solidify its economic and strategic presence in the Arctic, aligning with recent national strategies that emphasize energy independence and Arctic security. The Department of Defense (DoD) released the DoD Arctic Strategy of 2024, emphasizing US interests in Arctic security, following the 2023 ten-year plan called The National Strategy for the Arctic Region [

37]. These Arctic strategies, alongside the Department of the Interior using emergency authorities to streamline complex compliance processes from years to weeks, are intended to strengthen the nation’s energy security through more domestic resource production.

The MCDA framework outlined in

Table A2 and

Table A3 provided a transparent and quantitative ranking, identifying key candidates for further investigation in the feasibility of GtX to address a growing clean fuel need in the maritime industry. Unalaska, with a total score of 28, was followed by Adak (26) and Augustine Island (25). Unalaska’s high score largely comes from Accessibility and Infrastructure (year-round ice-free deepwater port: score of 5), Cargo Tonnage (highest tonnage of the Aleutian Island sites: score of 4), and a confirmed high temperature geothermal resource (194 °C: score of 3). This is on top of Unalaska’s history of seeking to develop the Makushin Volcano as a geothermal resource and its large commercial fishing and seafood processing industry. This overlap of factors positions Unalaska as a location well-suited as a GtX hub to meet existing maritime demand.

Given Unalaska’s existing push for geothermal energy and a deepwater port, it is an attractive choice. Industries like transportation or the fishing industry, which are large along Alaskan islands, are difficult to decarbonize using traditional battery or electric methods. GtX can serve as a foundation for a low-carbon future. Nome (21), along the Bering Strait, is a strategic gateway to the Arctic Ocean supported by a government push for a deepwater port. However, its low ranking is due to a moderate-temperature resource (146–154 °C), making it less favorable for high-efficiency electrolysis compared to the Aleutian Volcanic Arc locations. Augustine Island’s (25) geographic proximity to Anchorage and current geothermal investigation from GeoAlaska presents an interesting opportunity. More data is needed to confirm the size of the resource. Its high score also largely reflects its market potential, not the impacts of existing infrastructure and demand such as Unalaska. Akutan (20) and Adak Island (26) both have high-temperature geothermal reservoirs (Scores 2 and 4) but score lower in energy demand. Specifically, the lower Total Customers (Scores 1 and 2) and Cargo Tonnage (Scores 2 and 2) for both locations will make it a less-clear investment opportunity. Within the Aleutian Islands, Unalaska will have a higher local demand than Akutan or Adak, making it a less-risky investment.

Access to high-temperature volcanic resources is geographically limited; therefore, Alaska is well-suited to be an early adopter of GtX, reducing GHG emissions, increasing energy independence, and supporting local economies as a whole.

4.1. Policy and Social Barriers

While technical and economic models are compelling, the practical realization of GtX is linked to policy and establishing a Social License to Operate (SLO) with stakeholders. SLO is a complex social contract between industry and stakeholders to create a mutually beneficial, solution-oriented relationship [

38]. SLO is necessary for energy projects, as most technical barriers can be solved with investment and time; however, regaining lost trust is a more difficult barrier to overcome.

Meaningful engagement with local and Indigenous communities is key to this. Climate change disproportionately impacts these communities, from subsistence on traditional lands, addressing environmental concerns of an energy project, raising public awareness of how PtX works, to considering the economic impacts [

9,

28]. Many remote villages in Alaska face extreme energy costs. New energy projects in remote villages should seek to improve the local economy and cost of energy. Respecting the goals of each individual community is necessary to help reach everyone’s goal of affordable and reliable energy, a necessity in a region that reaches extreme temperatures. The state can also work to streamline permits, offer tax breaks, and alter fuel regulations to assist the energy transition [

12]. Training a local workforce and supply chain would reduce costs and increase community involvement in the project [

33].

A large-scale geothermal energy project would require a front-heavy investment. Establishing a market that investors feel stable investing in is necessary and largely achieved through long-term tax credits. The US four-year political cycle creates instability, as one administration’s policy can quickly be undone. However, geothermal energy has a bipartisan appeal as a reliable, high-capacity resource. Leveraging this bipartisan nature is necessary for enduring legislation to accelerate permits and creating market stability. On the international level, cohesive regulations will be needed to address global shipping, promote fair trade, and address climate concerns. Global superpowers taking steps towards decarbonization promotes investment in new technology and encourages other countries to step with them, such as the European Green Deal (2019) creating international interest in green hydrogen and “FuelEU Maritime” (2025) decarbonizing the shipping sector [

39]. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) implemented a phase Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) ban in 2024 to be fully enforced by 2029 to address shipping fuel emissions and oil spills in the Arctic [

7,

10]. In the US, the Biden administration released the first National Hydrogen Roadmap alongside the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, positioning the US as a technological leader in a carbon-free future [

40]. The International Energy Agency (IEA) found that under policy as of 2015 trending towards implementing policy in favor of geothermal energy, its TWh is predicted to increase four-fold from 72 to 299 [

15]. Carbon pricing in Arctic countries has been advantageous in encouraging geothermal technology development [

27]. As more policies encouraging decarbonization or green fuels are passed, a greater need for new solutions will emerge, as will its rate of growth.

4.2. Economic Viability

The economic analysis demonstrates that GtX can bypass the high and volatile costs of imported diesel that currently cripple many remote Alaskan communities. Geothermal energy’s low and predictable operating costs, combined with co-generated direct use, create a benefit for industrial and local uses. Geothermal energy’s baseload power is highly valuable to the system, creating a high LACE that intermittent renewables with a low LCOE do not. For microgrids and electrolyzers needing constant power, geothermal energy is an advantageous option. The remote Arctic setting of all five sites adds further cost concerns due to being an islanded microgrid. It is important to keep in mind that geothermal energy projects require high up-front costs and may take several years to become operational. Communities with current high electricity costs, such as Adak and Akutan (ranked 2 and 1), may be more likely to pursue a high-reward but high-investment resource such as geothermal energy.

Global regulatory mechanisms like the IMO’s HFO ban and ecotaxes will shift in favor of cleaner PtX fuels. GtX is scalable to meet these needs, particularly as long-distance shipping and industrial processing found in many Alaskan ports are not suited for electrification. Green hydrogen, ammonia, or other X products provide a low-carbon solution, particularly as 91.4% of Alaska’s energy consumption is not run on electricity and the largest consumers of energy in Alaska come from the industrial and transportation sectors, logging more than 81% of consumed energy [

28]. The global energy regime is not removing its reliance on fossil fuels anytime soon; however, industries and governments are under pressure to decarbonize. Even with fluctuations in subsidies within the US’s political state, renewable energy with no tax subsidies is still cost-competitive, especially with fast-growing energy demand [

41]. Ultimately, while the upfront costs of establishing a new resource are important, these costs must be weighed against the long-term risks of inaction. The Arctic is warming at a remarkable speed, largely due to GHG emissions into the atmosphere. By continuing to rely on fossil-fuel-based energy, and adding to these emissions, an unstable Arctic is inevitable. Further, in a world of changing global markets and geopolitical instability, reliance on imported goods and fuel is dangerous. By prioritizing domestic energy, Alaska can create a more resilient future.

4.3. Future Research

Future research should focus on emerging technologies to decrease the cost of GtX, monitor the increase in Arctic shipping route activity, and create a cost–benefit analysis of a chosen location building off of this state-wide assessment.

Table A4 provides a roadmap for stakeholders’ next steps in providing GtX fuels for the Arctic maritime sector.

Decrease Drilling Costs and Heat Loss: Prioritizing increasing research on supercritical fluids and the exploration of magmatic geothermal resources is crucial as it requires significant material science research to expand from a laboratory success to actual energy. Magmatic geothermal energy is a novel means of tapping into the thermal energy of magma chambers with extreme temperatures. This is a highly relevant method along the Aleutian Volcanic Arc, given the abundance of volcanic resources, that would offer a heat capacity 10 times higher than conventional, faster resource replenishment due to a magmatic convection cell [

18]. This overcomes limitations of heat loss in conventional geothermal systems, reducing construction costs by needing to drill fewer wells due to higher heat extraction per well. It is specifically good for GtX given that electrolysis, including HTSE, is most efficient at high temperatures [

17]. Finding ways to decrease costs and risk of drilling can also look like updated geophysical surveys of Alaska’s geothermal resources, research into new drilling technologies, and adopting modeling techniques from the oil and gas industry. Increased research into reservoir management and closed-loop geothermal energy to minimize environmental impacts will benefit the industry.

Site Specific Analysis: New advancements in material science, millimeter-wave drilling, or sensors could prevent direct contact with the fluids and mitigate temperature or pressure constraints. A comprehensive techno-economic analysis for a chosen location, starting with Unalaska, is the next step needed for various GtX applications in remote Arctic communities. This research should quantify the costs and benefits of different GtX pathways, considering the unique logistical constraints and energy demands of these regions. It should also evaluate the economic viability of combining resources for larger-scale PtX operations, as larger facilities often benefit from lower unit costs. Research into hybrid energy systems, combining geothermal with other renewable sources and storage solutions, will provide insight for years to come.

5. Conclusions

This study established GtX as a strategic choice for Alaska to address the growing energy demand. The state’s vast geothermal resources, particularly along the Aleutian Volcanic Arc, offer a secure, domestic, and cost-competitive lane to produce green fuels. These products are ideal for the maritime sector, as it will benefit from a reliable and economic source of X products as environmental policy trends towards stricter regulations. The core finding of the study is that Unalaska stands out as a strategic location for an initial GtX project. Its advantages include an existing deep-draft, ice-free port, high-temperature resource, a history of community engagement with geothermal energy, and proximity to Arctic shipping routes. By developing GtX in Unalaska, Alaska can solidify its role as a strategic gateway to the Arctic, reduce reliance on global supply chains and foreign energy, and establish a trade hub between North American and Indo-Pacific markets. Realizing the potential of this resource requires a strong SLO, built on meaningful partnerships with local and Indigenous communities and affordable regional energy. Geothermal energy’s growing interest in installation and bipartisan support should be capitalized on to pass legislation to streamline permits and create long-term tax incentives. De-risking investment is necessary to alleviate the high upfront investment of geothermal projects.

In conclusion, this research highlights the substantial potential for developing geothermal energy resources and their application in the maritime industry, supported by a favorable societal and political environment, laying the groundwork for Alaska’s clean and local energy future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and M.d.W.; methodology, E.C.; validation, E.C. and M.d.W.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C.; writing—review and editing, E.C. and M.d.W.; visualization, E.C.; supervision, M.d.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (Grant #2150389) through ACEP’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates program.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Alaska Center of Energy and Power at the University of Alaska Fairbanks for the Research Experience for Undergraduates.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAHSB | Central Alaska Hot Springs Belt |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DoD | Department of Defense |

| DOE | Department of Energy |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gases |

| GtX | Geothermal-to-X |

| HTSE | High-Temperature Steam Electrolysis |

| J | Joules |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| LACE | Levelized Avoided Cost of Electricity |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| LLC | Limited Liability Corporation |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| NSR | Northern Sea Route |

| NWP | Northwest Passage |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PtX | Power-to-X |

| SLO | Social License to Operate |

| TPR | Transpolar Route |

| USACE | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Levelized Costs of Energy (LCOE) for major electricity generation technologies (USD/MWh). Values not listed in the compiled reports are noted by NL.

Table A1.

Levelized Costs of Energy (LCOE) for major electricity generation technologies (USD/MWh). Values not listed in the compiled reports are noted by NL.

| Energy Source | Predicted

2022 [15] | Real 2016–2023 [13] | Real 2023 [25] | Real 2024 [41] | Predicted 2026 [14] | Predicted 2027 [42] | Average |

|---|

| Solar Photovoltaic | 85 | 44 | 29–284 | 38–217 | 33 | 36.5 | 80.42 |

| Onshore Wind | 65 | 33 | 27–73 | 37–86 | 37 | 40.23 | 47.79 |

| Offshore Wind | 158 | 75 | 74–139 | 70–157 | 121 | 136.5 | 118.42 |

| Geothermal | 45 | 71 | 64–106 | 66–109 | 36 | 39.8 | 60.72 |

| Hydroelectric | 68 | 57 | NL | NL | 56 | 64.3 | 61.33 |

| Coal | 140 | NL | 69–168 | 71–173 | 73 | 82.6 | 107.22 |

| Combined Cycle | 57 | NL | 45–108 | 48–109 | 37 | 39.9 | 57.78 |

Table A2.

Data matrix compiling information about the five sites of this study from three perspectives: Geothermal Resource Quality, Energy Demand, and Accessibility and Infrastructure.

Table A2.

Data matrix compiling information about the five sites of this study from three perspectives: Geothermal Resource Quality, Energy Demand, and Accessibility and Infrastructure.

| | | Adak | Unalaska | Akutan | Nome | Augustine Island | Anchorage |

|---|

| General Information | Latitude [34] | 51.8682 | 53.8731 | 54.1343 | 64.4981 | 59.3725 | 61.2163 |

| Longitude [34] | −176.6403 | −166.5377 | −165.7735 | −165.4086 | −153.4358 | −149.8948 |

| Port Name | Port of Adak | International Port of Dutch Harbor | Port of Akutan | Port of Nome | NA | Port of Alaska |

| Native People | | | | Central Yup’ik | | Dena’ina |

| Geothermal Resource Name | Mount Adakak | Makushin Volcano | Akutan Volcano | Pilgrim Hot Springs | Mount Augustine | NA |

| State Owned Geothermal Resource | No (Aleut Corporation (Anchorage, AK, USA)) | No (Ounalashka Native Corporation (Unalaska, AK, USA)) | No (Native Village of Akutan) | No (Unaatuq, LLC (Nome, AK, USA)) | Yes | NA |

| Geothermal Resource Quality | Geothermal Resource Temperature [26,31,35] | 150 °C | 194 °C | 200–240 °C | 146–154 °C | 250 °C | NA |

| Energy Demand | Residential Customers (2021) [34] | 78 | 779 | 50 | 1754 | NA | 96,560 |

| Commercial Customers (2021) [34] | 10 | 57 | 11 | 73 | NA | 16,232 |

| Residential Mwh (2021) [34] | 165 | 3960 | 201 | 8780 | NA | 613,667 |

| Commercial Mwh (2021) [34] | 441 | 37,634 | 210 | 9640 | NA | 1,259,354 |

| Residential Energy Price (2021) USD/kWh [34] | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.2 | 0.28 | NA | 0.21 |

| Commercial Energy Price (2021) USD/kWh [34] | 1.27 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.36 | NA | 0.16 |

| Average Energy Cost USD/kWh [34] | 1.06 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.32 | NA | 0.18 |

| Cargo Tonnage (2023) [43] | NL | 1,171,539 | NL | 203,434 | NA | 4,044,294 |

| Accessibility and Infrastructure | Ice-Free | Year-round | Year-round | Year-round | May to December | Year-round | Year-round |

| Airport [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Harbor [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dock [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cargo [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Barge [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coastal [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| State Ferry [34] | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Road Connection [34] | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Port Type [29] | Deepwater | Deepwater | Shallow | Deepwater | NA | Deepwater |

| Military Infrastructure | Yes (Former Naval Air Station) | Yes (Active Coast Guard Station) | No | Yes (Active Army National Guard) | No | Yes (Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER)) |

Table A3.

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis based on values and context provided in

Table A2. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis used to rank the five sites for a preliminary feasibility assessment.

Table A3.

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis based on values and context provided in

Table A2. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis used to rank the five sites for a preliminary feasibility assessment.

| | Criteria | Adak | Unalaska | Akutan | Nome | Augustine Island |

|---|

| Geothermal Resource Quality | Geothermal Resource Temperature | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Energy Demand | Total Customers | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 * |

| Cargo Tonnage (per year) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 * |

| Average Energy Price | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 * |

| Accessibility and Infrastructure | Port Operability (Ice) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Military Infrastructure | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Port Type | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| | Total Score | 26 | 28 | 20 | 21 | 25 |

Table A4.

Roadmap of future research for stakeholders.

Table A4.

Roadmap of future research for stakeholders.

| Timeframe | Priorities | Concrete Steps |

|---|

| Near-Term (1–3 years) | Site-specific techno-economic analysis for Unalaska | Acquire funding and regulatory approval. Initiate SLO within the community, starting with a formal partnership and a revenue-sharing agreement. Perform geophysical surveys to confirm reservoir quality. |

| Medium-Term (3–7 years) | Pilot studies on advanced drilling and modeling techniques | Confirm resource through in situ well flow tests. Begin construction of the GtX facility, grid, and port requirements. Encourage vessels to re-fit for X product storage and use. |

| Long-Term (7+ years) | Advanced research on magmatic geothermal energy extraction | Begin operations at the Unalaska facility, including wellfield development and electrolyzer construction. Continue research on magmatic resource potential. Explore GtX potential at other Alaska sites. |

Table A5.

International and national level policy with an anticipated impact on the Geothermal-to-X (GtX) transition.

Table A5.

International and national level policy with an anticipated impact on the Geothermal-to-X (GtX) transition.

| Policy | Scope | Status (November 2025) | Impact on GtX |

|---|

| European Green Deal | EU-wide Climate | In effect (to reach EU climate neutrality goal by 2050) | Creates international interest in green hydrogen technology [39]. |

| Fuel EU Maritime | EU Shipping | Adopted (entered in 2023, phased in 2025) | Imposes mandatory limits of greenhouse gas intensity of energy used by ships, creating demand for alternatives [39]. |

| IMO Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) Ban | Global Shipping | In effect (entered in 2024, full enforcement by 2029) | Phased ban on use of HFO in the Arctic, accelerating the need for cleaner shipping fuels [7,10]. |

| U.S. National Hydrogen Roadmap | U.S. Strategy | In effect (2024) | Established hydrogen as a priority of the U.S., encouraging innovation and investment in the industry [40]. |

| Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) | U.S. Strategy | In effect (2022) | A financial incentive to de-risk hydrogen production, including Section 45V Clean Hydrogen Production Tax Credit (PTC) [40]. |

| Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) | U.S. Strategy | In effect (2021–2026) | Allocated money towards developing Clean Hydrogen Hubs and set a goal of decreasing clean hydrogen costs to under 2 USD/kg by 2026 [40]. |

Figure A1.

Map of the Arctic shipping routes: Northwest Passage (NWP), Northern Sea Route (NSR), and the Transpolar Route (TPR). The dark blue circle denotes the Arctic Circle. The map on the right focuses on Alaska, near-Arctic ports, the geothermal locations mentioned in this study, and locations of US military presence in Alaska.

Figure A1.

Map of the Arctic shipping routes: Northwest Passage (NWP), Northern Sea Route (NSR), and the Transpolar Route (TPR). The dark blue circle denotes the Arctic Circle. The map on the right focuses on Alaska, near-Arctic ports, the geothermal locations mentioned in this study, and locations of US military presence in Alaska.

Figure A2.

Flowchart demonstrating the urgency and cyclical nature of inevitable climate change on the need for secure energy in the Arctic.

Figure A2.

Flowchart demonstrating the urgency and cyclical nature of inevitable climate change on the need for secure energy in the Arctic.

Figure A3.

Methodology map to address a gap in the literature on GtX and provide specific insight for stakeholders in a rapidly changing Arctic maritime industry.

Figure A3.

Methodology map to address a gap in the literature on GtX and provide specific insight for stakeholders in a rapidly changing Arctic maritime industry.

Figure A4.

Conceptual equations of Levelized Avoided Cost of Electricity (LACE) and Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE).

Figure A4.

Conceptual equations of Levelized Avoided Cost of Electricity (LACE) and Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE).

Figure A5.

Geothermal-to-X methods showing how geothermal resources at different temperature ranges are converted through specific processes into various end products X, including ammonia, methanol, and e-fuels [

20].

Figure A5.

Geothermal-to-X methods showing how geothermal resources at different temperature ranges are converted through specific processes into various end products X, including ammonia, methanol, and e-fuels [

20].

Figure A6.

The average LCOE values of seven different energy technologies collected from non-site-specific literature, which contributes to high variance (

Table A1).

Figure A6.

The average LCOE values of seven different energy technologies collected from non-site-specific literature, which contributes to high variance (

Table A1).

References

- Rantanen, M.; Karpechko, A.Y.; Lipponen, A.; Nordling, K.; Hyvärinen, O.; Ruosteenoja, K.; Vihma, T.; Laaksonen, A. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, I.H.; Ahmed, R.; Ford, J.D.; Hamidi, A.R. Arctic Warming: Cascading Climate Impacts and Global Consequences. Climate 2025, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, Z. From melting ice to green shipping: Navigating emission reduction challenges in Arctic shipping in the context of climate change. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1462623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidek, J. SEOC Update: 2025 October West Coast Storm—Situation Update (Press-Release). 2025. Available online: https://ready.alaska.gov/Documents/PIO/PressReleases/2025.10.13_Press%20Release%20-%20%202025%20October%20West%20Coast%20Storm%20Oct.%2013.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lovecraft, A.; Boylan, B.; Burke, N.; Glover, A.; Parlato, N.; Robb, K.; Thoman, R.; Walsh, J.; Watson, B. Alaska’s Changing Arctic: Energy Issues and Trends for the Alaska State Legislature and Its Citizens; Center for Arctic Policy Studies, International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2023; Available online: https://uaf-iarc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Alaskas-Changing-Arctic-Energy-Issues-and-Trends-2023.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Lynch, A.H.; Norchi, C.H.; Li, X. The interaction of ice and law in Arctic marine accessibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, 2202720119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, K. Decarbonizing Arctic shipping: Governance pathways and future directions. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1489091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Review of Maritime Transport 2024|Navigating Maritime Chokepoints; UN Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2024 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Alaska State Energy Profile. 2025. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/state/print.php?sid=AK (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Atilhan, S.; Park, S.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Atilhan, M.; Moore, M.; Nielsen, R.B. Green hydrogen as an alternative fuel for the shipping industry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiru, A.R.; Vuokila, A.; Huuhtanen, M. Recent development in Power-to-X: Part I—A review on techno-economic analysis. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, E.; Koleva, M.; Kilcher, L.; Raun, J. Alaska Hydrogen Opportunities Report; Alaska Center for Energy and Power, University of Alaska: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2023. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2024/Sep/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2023 (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Levelized Costs of New Generation Resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2021; U.S. Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Logan, J.; Marcy, C.; McCall, J.; Flores-Espino, F.; Bloom, A.; Aabakken, J.; Cole, W.; Jenkin, T.; Porro, G.; Liu, C.; et al. Electricity Generation Baseline Report; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C.; Blondeel, M.; Bradshaw, M.; Bridge, G.; Faigen, E.; Fletcher, L. Rethinking Energy Geopolitics: Towards a Geopolitical Economy of Global Energy Transformation. Geopolitics 2024, 30, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlehdar, M.; Beardsmore, G.; Narsilio, G.A. Hydrogen production from low-temperature geothermal energy—A review of opportunities, challenges, and mitigating solutions. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 77, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elders, W.; Shnell, J.; Albertsson, A.; Friðleifsson, G.; Zierenberg, R. Improving Geothermal Economics by Utilizing Supercritical and Superhot Systems to Produce Flexible and Integrated Combinations of Electricity, Hydrogen, and Minerals. GRC Trans. 2018, 42, 1034002. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Dehshiri, S.J.H.; Dehshiri, S.S.H. Ranking locations for producing hydrogen using geothermal energy in Afghanistan. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 15924–15940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Om, H.; Sircar, A.; Gautam, T.; Yadav, K.; Bist, N. Comprehensive Review of Hydrogen generation utilising Geothermal Energy. Unconv. Resour. 2024, 5, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, A.; Previtali, D.; Pirola, C.; Bozzano, G.; Nadezhdin, I.S.; Goryunov, A.G.; Manenti, F. H2S in Geothermal Power Plants: From Waste to Additional Resource for Energy and Environment. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 70, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, N.; Fazeli, R.; Tzschockel, T.S.; Dillman, K.J.; Heinonen, J. Stakeholder and Techno-Economic assessment of Iceland’s green hydrogen economy. Energies 2025, 18, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zun, M.T.; McLellan, B.C. Cost projection of global green hydrogen production scenarios. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 932–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.; Schönfisch, M.; Schulte, S. Estimating global production and supply costs for green hydrogen and hydrogen-based green energy commodities. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 48, 9139–9154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard. Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis—Version 17.0. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2024-12/34-%20Exh.%20FF-%20Lazard%27s.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Miller, T.P. The Geology of North America; The Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1994. Available online: https://dggs.alaska.gov/webpubs/outside/text/dnag_ch16.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Kolker, A.; Garber-Slaght, R.; Anderson, B.; Reber, T.; Zyatitsky, K.; Pauling, H.; National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Geothermal Energy and Resilience in Arctic Countries; Technical Report NREL/TP-5700-80928; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy22osti/80928.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Meadows, R.; Cooperman, A.; Koleva, M.; Draxl, C.; Kilcher, L.; Baca, E.; Strout Grantham, K.; DeGeorge, E.; Musial, W.; Wiltse, N.; et al. Feasibility Study for Renewable Energy Technologies in Alaska Offshore Waters; Report OCS Study BOEM 2023-076; U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Alaska OCS Region: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2023. Available online: https://espis.boem.gov/final%20reports/BOEM_2023-076.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- United States Army Corps of Engineers. Alaska Deep-Draft Arctic Port System Study; United States Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- U.S. Department of the Interior; U.S. Geological Survey. Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal: Estimates of Undiscovered Oil and Gas North of the Arctic Circle. U.S. Geological Survey, 2008; USGS Fact Sheet 2008-3049. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3049/fs2008-3049.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Smith, R.; Ikelman, J.; National Geophysical Data Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Geothermal Resources of Alaska; Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1983.

- Georgeff, E.; Mao, X.; Rutherford, D. Scaling US Zero-Emission Shipping: Potential Hydrogen Demand at ALEUTIAN Islands Ports; The International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Aleutian-Islands-potential_FINAL-1.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Meadows, R.; Edgerly, E.; Jordan, R.; Beshilas, L. Renewable Energy Integration in Remote Alaska Communities; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2023. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy25osti/90685.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Alaska Center for Energy and Power (ACEP); Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER). Alaska Energy Data Gateway v3.0. Available online: https://akenergygateway.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Bergfeld, D.; Lewicki, J.L.; Evans, W.C.; Hunt, A.G.; Revesz, K.; Huebner, M. Geochemical Investigation of the Hydrothermal System on Akutan Island, Alaska, July 2012; Scientific Investigations Report 2013–5231; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2014. [CrossRef]

- GeoAlaska LLC. Projects. Available online: https://geoalaska.wixsite.com/geoalaska/projects (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- The White House. Declaring a National Energy Emergency. 2025. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/declaring-a-national-energy-emergency/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Barich, A.; Stokłosa, A.W.; Hildebrand, J.; Elíasson, O.; Medgyes, T.; Quinonez, G.; Casillas, A.C.; Fernandez, I. Social license to operate in geothermal energy. Energies 2021, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimova, T.; Lagouvardou, S.; Kian, H.; Breyer, C. Comparing sustainable fuel adoption in the energy transition for maritime and aviation transport. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. U.S. National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Lazard. Lazard’s 2025 LCOE+; Lazard, 2025. Available online: https://www.lazard.com/media/eijnqja3/lazards-lcoeplus-june-2025.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Levelized Costs of New Generation Resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2022; U.S. Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/electricity_generation.php (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Institute for Water Resources (IWR), Waterborne Commerce Statistics Center (WCSC). WCSC—Waterborne Commerce Statistics Center. Available online: https://www.iwr.usace.army.mil/About/Technical-Centers/WCSC-Waterborne-Commerce-Statistics-Center/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).