Phytoremediation of Co-Contaminated Environments: A Review of Microplastic and Heavy Metal/Organic Pollutant Interactions and Plant-Based Removal Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search Strategy

3. Phytoremediation

3.1. Secondary Metabolites in Phytoremediation

3.2. Molecular and Genetic Basis of Phytoremediation: Advances and Applications in Genoremediation

4. Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated with Microplastics

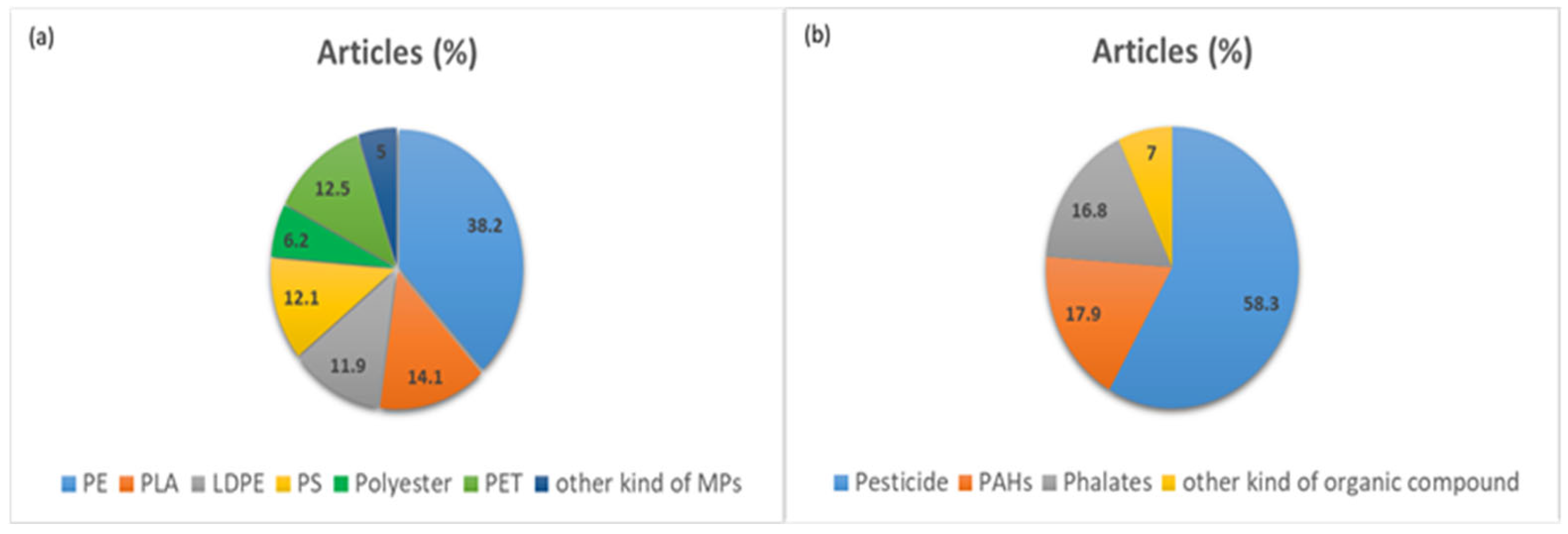

5. Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated with Microplastics Encapsulated Other Organic Contaminants

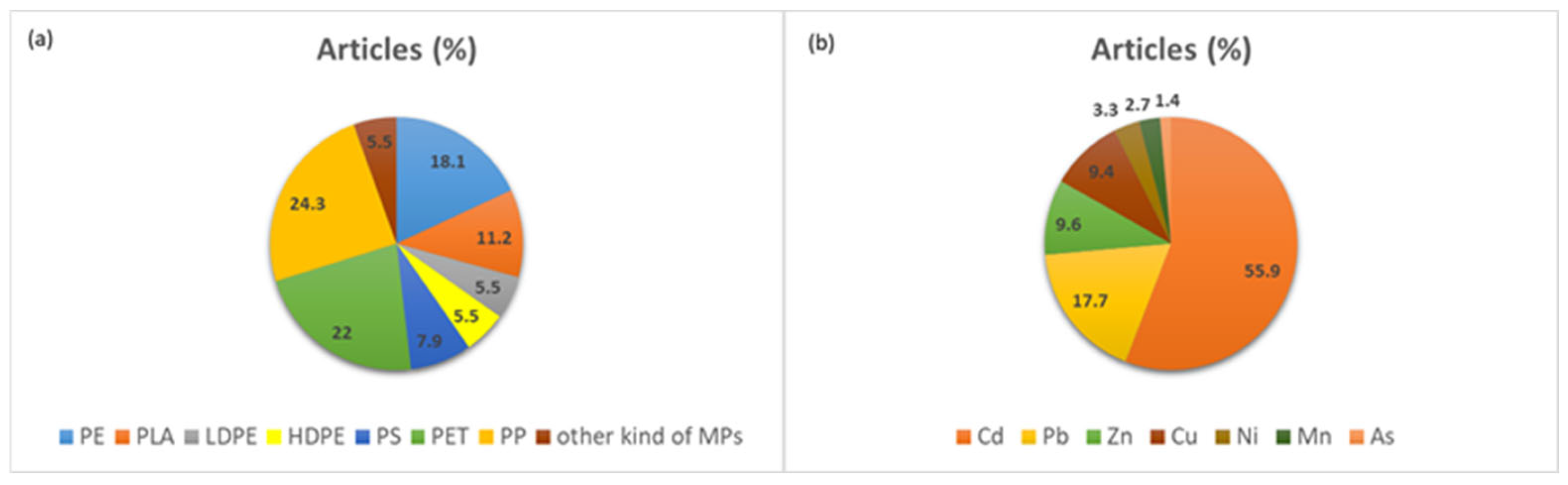

6. Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated Microplastics Encapsulated Heavy Metals

7. Effects on Soils and Plants

7.1. Organic Pollutants

7.2. Heavy Metals

7.3. Thematic Overview and Synthesis of Literature

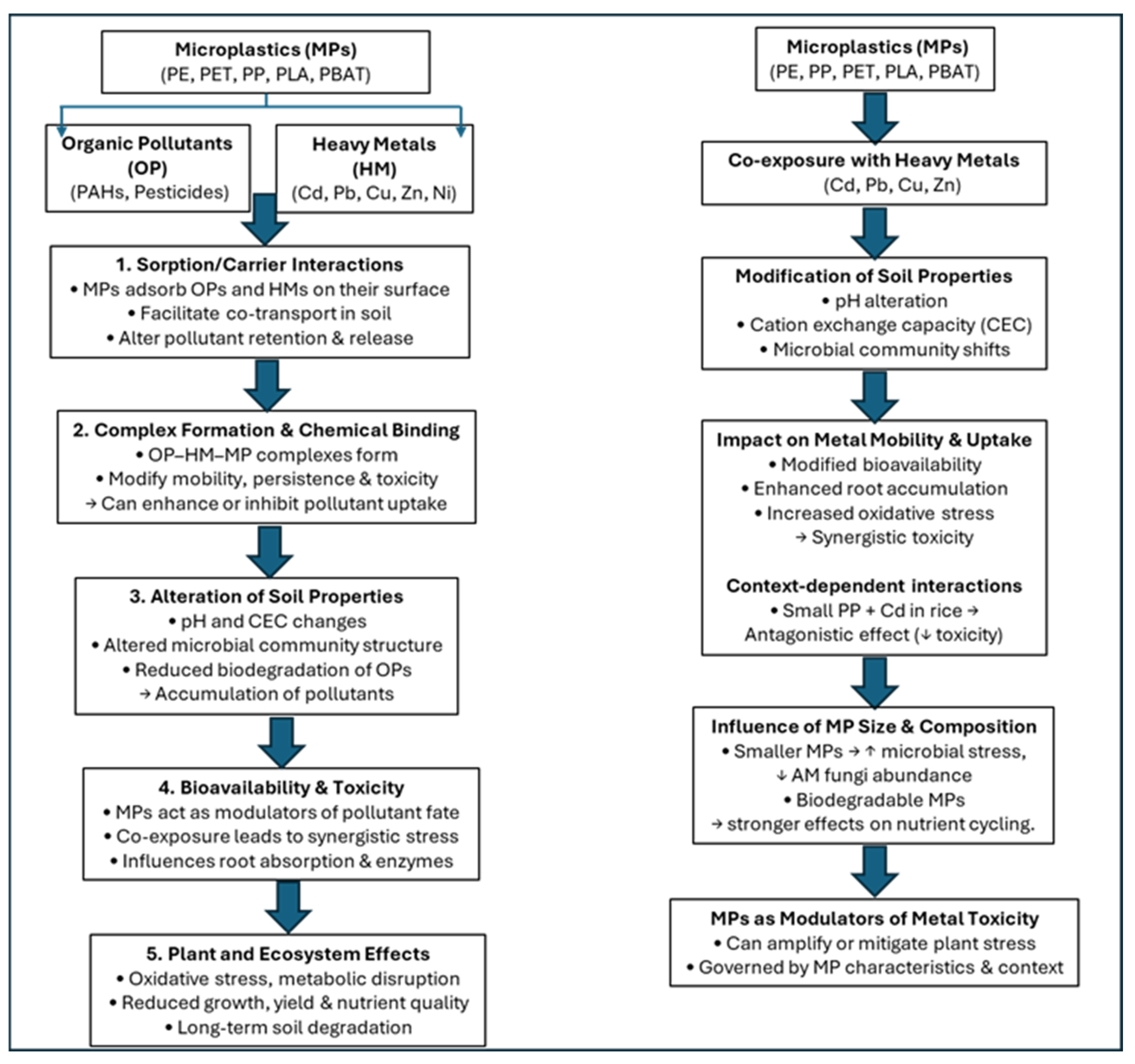

7.3.1. General Patterns and Mechanisms of Interaction

7.3.2. Effects of MPs Combined with Organic Pollutants

7.3.3. MPs and Heavy Metals: Synergistic and Antagonistic Effects

7.3.4. Influence of Microplastics–Pollutant Complexes on Plant Metabolic Functions

8. Key Challenges and Emerging Strategies for Phytoremediation Under Co-Contamination Conditions

8.1. Key Bottlenecks in Co-Contaminant Phytoremediation

8.2. Aged MPs vs. Pristine MPs

8.3. Comparative Assessment: Phytoextraction vs. Phytostabilization in Co-Contaminated Soils

8.4. Coherent Frameworks and Emerging Trends in Phytoremediation Under Co-Contamination Conditions

8.5. Decision Framework for Plant Choice Under Combined Pollution

8.6. Emerging Biotechnologies: Genetically Edited Hyperaccumulators and Advances in Addressing Co-Contamination

8.7. New Ideas and Approaches

8.8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

8.9. Socio-Economic Feasibility and Policy Considerations for Phytoremediation

8.10. Challenges and Case Studies from Agriculture-Dominant and Developing Regions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

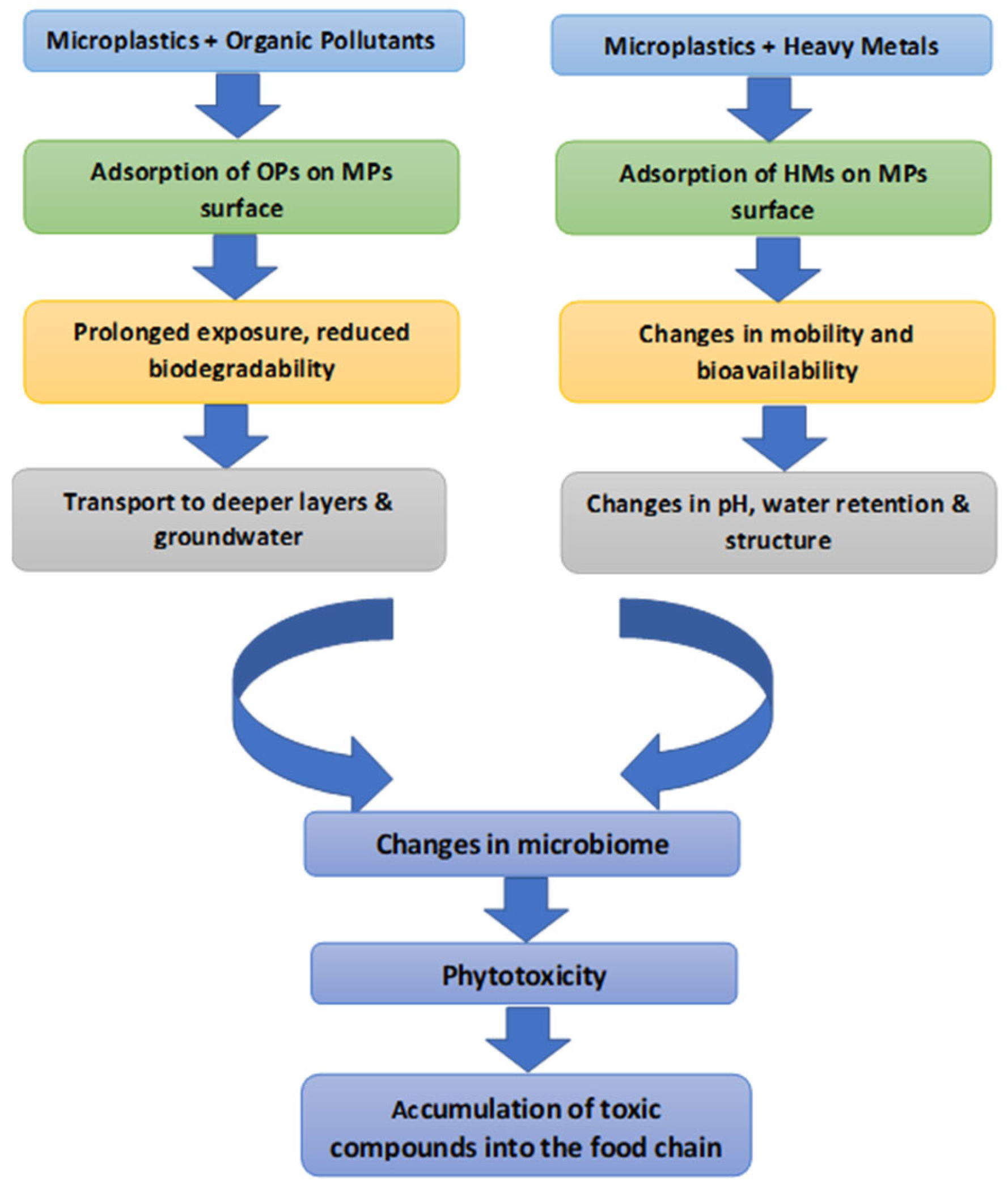

| Stage/Process in Figure 1 | Description | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorption of Organic Pollutants on MPs surface | MPs adsorb organic pollutants including PAHs, PCBs and pesticides, due to hydrophobic and surface properties. | [91] |

| Adsorption of Heavy Metals on MPs surface | Heavy metals such as Pb, Cd, and Cu associate with MPs via electrostatic interactions and functional groups. | [91] |

| Prolonged exposure, reduced biodegradability | Extended exposure of soils to MPs causes surface aging and inhibits microbial activity, which leads to decreased biodegradability and a reduction in the effectiveness of biotic degradation and phytoremediation processes. | [89,92] |

| Transport to deeper layers and groundwater | Combination of MPs and organic pollutants increases persistence and facilitates transport to groundwater. | [93,94] |

| Changes in mobility and bioavailability | MPs modify the bioavailability of heavy metals and other pollutants in soil systems. | [94] |

| Changes in pH, water retention and structure | MPs affect soil physicochemical properties (e.g., pH, porosity, and water-holding capacity). | [95] |

| Changes in microbiome | Changes in soil properties result in variations in the composition and function of microbial communities. | [96] |

| Phytotoxicity | The combination of MPs and pollutants leads to oxidative stress and inhibit plant growth. | [80] |

| Accumulation of toxic compounds into the food chain | Toxic compounds and MPs are passed on to higher trophic levels via the food web. | [81] |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, T.; Wang, J.; Ge, Y. Enhanced Phytoremediation of Mixed Heavy Metal (Mercury)-Organic Pollutants (Trichloroethylene) with Transgenic Alfalfa Co-Expressing Glutathione S-Transferase and Human P450 2E1. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapliyal, C.; Priya, A.; Singh, S.B.; Bahuguna, V.; Daverey, A. Potential Strategies for Bioremediation of Microplastic Contaminated Soil. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 6, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.A.; Costa, J.; Cumbane, B.; Abias, M.; Pires, J.R.A.; Souza, V.G.L.; Santos, F.; Fernando, A.L. Combating Climate Change with Phytoremediation. Is It Possible? In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Water Energy Food and Sustainability (ICoWEFS 2022), Portalegre, Portugal, 10–12 May 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Du, Y.; Sheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wan, C.; Dong, H.; Gu, J.; Long, H.; Zhang, H. Assessment of Microplastic Ecological Risk and Environmental Carrying Capacity of Agricultural Soils Based on Integrated Characterization: A Case Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 960, 178375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Bahar, M.M.; Naidu, R. Diffuse Soil Pollution from Agriculture: Impacts and Remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziourrou, P.; Golia, E.E. Plastics in Agricultural and Urban Soils: Interactions with Plants, Micro-Organisms, Inorganic and Organic Pollutants: An Overview of Polyethylene (PE) Litter. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinigopoulou, V.; Pashalidis, I.; Kalderis, D.; Anastopoulos, I. Microplastics as Carriers of Inorganic and Organic Contaminants in the Environment: A Review of Recent Progress. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 350, 118580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Peng, N.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, X. A Critical Review of Co-Pollution of Microplastics and Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soil Environments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 286, 117248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.; Costa, J.; Boléo, S.; Duarte, M.P.; Fernando, A.L. Phytoremediation of Inorganic Compounds. In Electrokinetics Across Disciplines and Continents; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 373–399. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazaryan, K.; Agrawal, S.; Margaryan, G.; Harutyunyan, A.; Rajput, P.; Movsesyan, H.; Rajput, V.D.; Singh, R.K.; Minkina, T.; Elshikh, M.S.; et al. Soil Pollution: An Agricultural and Environmental Problem with Nanotechnological Remediation Opportunities and Challenges. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralinda, R.; Miller, P.G. Phytoremediation; Technology Overview Report; Ground-Water Remediation Technologies Analysis Center: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, R.L. Plant Uptake of Inorganic Waste Constituents. In Land Treat of Hazard Wastes; Noyes Data Corporation: Park Ridge, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli, F.M.P.; Bhat, R.A.; Dar, G.H.; Hakeem, K.R. The History of Phytoremediation. In Phytoremediation: Biotechnological Strategies for Promoting Invigorating Environs; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, C.; Black, C.R. One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: The Evolution of Phytoremediation into Commercial Technologies. Biosci. Horiz. 2014, 7, hzu009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Javaid, A.; Abideen, Z.; Duarte, B.; Jarar, H.; El-Keblawy, A.; Sheteiwy, M.S. The Potential of Zeolite Nanocomposites in Removing Microplastics, Ammonia, and Trace Metals from Wastewater and Their Role in Phytoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 1695–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golia, E.E.; Liava, V.; Achilias, D.S.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Zorpas, A.A.; Bethanis, J.; Girousi, S. Microplastics’ Impact on Soil Health and Quality: Effect of Incubation Time and Soil Properties in Soil Fertility and Pollution Extent under the Circular Economy Concept. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2024, 43, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethanis, J.; Golia, E.E. Revealing the Combined Effects of Microplastics, Zn, and Cd on Soil Properties and Metal Accumulation by Leafy Vegetables: A Preliminary Investigation by a Laboratory Experiment. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziourrou, P.; Papatheodorou, E. Microplastics: Is There Any Environmental Information about Insect Glue Trap Plastic (IGTP)? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 15323–15324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Shi, G.; Zou, D.; Wu, Z.; Qin, P.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y. Micro- and Nano-Plastics Pollution and Its Potential Remediation Pathway by Phytoremediation. Planta 2023, 257, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Murtaza, B.; Bibi, I.; Dumat, C. A Comparison of Technologies for Remediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 182, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Badu, B.; Kgorutla, L.E.; Li, S.S.; Danso, P.O.; Xue, Z.; Qiang, G. Phytoremediation of Organic and Inorganic Compounds in a Natural and an Agricultural Environment: A Review. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2020, 18, 6875–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, B.; Liang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, J. Prospect of Phytoremediation Combined with Other Approaches for Remediation of Heavy Metal-Polluted Soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 16069–16085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Rawat, S.; Rautela, A. Phytoremediation in Sustainable Wastewater Management: An Eco-Friendly Review of Current Techniques and Future Prospects. AQUA—Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2024, 73, 1946–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltse, C.C.; Rooney, W.L.; Chen, Z.; Schwab, A.P.; Banks, M.K. Greenhouse Evaluation of Agronomic and Crude Oil-Phytoremediation Potential among Alfalfa Genotypes. J. Environ. Qual. 1998, 27, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, K.; Li, J.; Anandkumar, A.; Leng, Z.; Zou, C.B.; Du, D. Managing Environmental Contamination through Phytoremediation by Invasive Plants: A Review. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 138, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyar, R.; Doulati Ardejani, F.; Norouzi, P.; Maghsoudy, S.; Yavarzadeh, M.; Taherdangkoo, R.; Butscher, C. Phytoremediation Potential of Native Hyperaccumulator Plants Growing on Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soil of Khatunabad Copper Smelter and Refinery, Iran. Water 2022, 14, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Wei, C.; Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, D. Heavy Metals Uptake and Transport by Native Wild Plants: Implications for Phytoremediation and Restoration. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjimi, B. Phytoremediation: A Sustainable Environmental Technology for Heavy Metals Decontamination. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaňares, E.; Lojka, B. Potential Hyperaccumulator Plants for Sustainable Environment in Tropical Habitats. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 528, 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolsby, E.W.; Mason, C.M. Toward a More Physiologically and Evolutionarily Relevant Definition of Metal Hyperaccumulation in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A.; Timilsina, A.; Gautam, A.; Adhikari, K.; Bhattarai, A.; Aryal, N. Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, Plant Selection and Enhancement by Natural and Synthetic Agents. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadia, C.D.; Fulekar, M.H. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals: Recent Techniques. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Limmer, M.; Burken, J. Phytovolatilization of Organic Contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6632−6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Singh, P.; Siddiqui, H.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Salinity Induced Physiological and Biochemical Changes in Plants: An Omic Approach towards Salt Stress Tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Yasmin, A.; Fariq, A. Metabolites Produced by Inoculated Vigna Radiata during Bacterial Assisted Phytoremediation of Pb, Ni and Cr Polluted Soil. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossel, A. Ueber die Chemische Zusammensetzung der Zelle. Du. Bois-Reymond’s Archiv./Arch. Anat. Physiol. Physiol. Abt. 1891, 278, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Elhamouly, N.A.; Hewedy, O.A.; Zaitoon, A.; Miraples, A.; Elshorbagy, O.T.; Hussien, S.; El-Tahan, A.; Peng, D. The Hidden Power of Secondary Metabolites in Plant-Fungi Interactions and Sustainable Phytoremediation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1044896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M. Heavy Metal Stress in Plants: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, P.; Dutta, J.; Roy, M.; Thakur, T.K.; Mitra, A. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacterial Secondary Metabolites in Augmenting Heavy Metal(Loid) Phytoremediation: An Integrated Green in Situ Ecorestorative Technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 55851–55894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.C.; Nocchi, S.R.; Luiz, J.R.; do Nascimento, V.A.; Carollo, C.A. Reevaluating the Role of Secondary Metabolites in Cadmium Phytoremediation. Environ. Monit. Assess 2025, 197, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumya, V.; Sowjanya, A.; Kiranmayi, P. Evaluating the Status of Phytochemicals within Catharanthus Roseus Due to Higher Metal Stress. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2021, 23, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadimou, S.G.; Golia, E.E.; Barbayiannis, N.; Tsiropoulos, N.G. Dual Role of the Hyperaccumulator Silybum Marianum (L.) Gaertn. in Circular Economy: Production of Silymarin, a Valuable Secondary Metabolite, and Remediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 38, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilou, C.; Tsiropoulos, N.G.; Golia, E.E. Phytoremediation & Valorization of Cu-Contaminated Soils Through Cannabis sativa (L.) Cultivation: A Smart Way to Produce Cannabidiol (CBD) in Mediterranean Soils. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liava, V.; Karkanis, A.; Tsiropoulos, N. Yield and Silymarin Content in Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn.) Fruits Affected by the Nitrogen Fertilizers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 171, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Ouyang, W.; Hong, Y.; Liao, D.; Khan, S.; Li, H. Responses of Endophytic and Rhizospheric Bacterial Communities of Salt Marsh Plant (Spartina alterniflora) to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Contamination. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syranidou, E.; Thijs, S.; Avramidou, M.; Weyens, N.; Venieri, D.; Pintelon, I.; Vangronsveld, J.; Kalogerakis, N. Responses of the Endophytic Bacterial Communities of Juncus acutus to Pollution with Metals, Emerging Organic Pollutants and to Bioaugmentation with Indigenous Strains. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 871, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Li, X.B.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.X.; Ren, L.L.; Dong, B.; Li, W.; Xie, W.J.; Yao, Z.G.; Chen, Q.F.; et al. Diversity and Functional Characteristics of Endophytic Bacteria from Two Grass Species Growing on an Oil-Contaminated Site in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzejewska, E.; Urbaniak, M.; Zagibajło, K.; Vangronsveld, J.; Thijs, S. The Effect of Syringic Acid and Phenoxy Herbicide 4-Chloro-2-Methylphenoxyacetic Acid (MCPA) on Soil, Rhizosphere, and Plant Endosphere Microbiome. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 882228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzejewska, E.; Tołoczko, W.; Urbaniak, M. Behind the Plant-Bacteria System: The Role of Zucchini and Its Secondary Metabolite in Shaping Functional Microbial Diversity in MCPA-Contaminated Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewska-Sinner, E.; Thijs, S.; Vangronsveld, J.; Urbaniak, M. Towards Enhancing Phytoremediation: The Effect of Syringic Acid, a Plant Secondary Metabolite, on the Presence of Phenoxy Herbicide-Tolerant Endophytic Bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, A.A.; Lejcuś, K.; Fiałkiewicz, W.; Marczak, D. Advancing Phytoremediation: A Review of Soil Amendments for Heavy Metal Contamination Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Shinde, A.; Aeron, V.; Verma, A.; Arif, N.S. Genetic Engineering of Plants for Phytoremediation: Advances and Challenges. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Nawaz, M.F.; Gul, S.; Yasin, G.; Hussain, B.; Li, Y.; Cheng, H. State-of-the-Art OMICS Strategies against Toxic Effects of Heavy Metals in Plants: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 242, 113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.C.; Crowley, D.E.; Thompson, I.P. Secondary Plant Metabolites in Phytoremediation and Biotransformation. Trends Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, J.H. Molecular Mechanisms in Phytoremediation of Environmental Contaminants and Prospects of Engineered Transgenic Plants/Microbes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Kumar, V.; Lee, S.S.; Raza, N.; Kim, K.H.; Ok, Y.S.; Tsang, D.C.W. Nanoparticle-Plant Interaction: Implications in Energy, Environment, and Agriculture. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, J.; Kailasa, S.K.; Kwon, E.E.; Tsang, Y.F.; Ok, Y.S.; Kim, K.H. A Critical Review of Ferrate(VI)-Based Remediation of Soil and Groundwater. Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 420–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, E.; Khan, M.T.; Irem, S. Biochemical Mechanisms of Signaling: Perspectives in Plants under Arsenic Stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Y.; Sahito, Z.A.; Tian, S.; Yang, X. Nicotianamine Synthase Gene 1 from the Hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance Is Associated with Cd/Zn Tolerance and Accumulation in Plants. Plant Soil 2019, 443, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.R.; Silva, H.F.; Brignoni, A.S.; Silva, F.G.; Camargos, L.S.; Souza, L.A. Characterization of Biomass Sorghum for Copper Phytoremediation: Photosynthetic Response and Possibility as a Bioenergy Feedstock from Contaminated Land. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2019, 25, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Hamid, Y.; Gurajala, H.K.; He, Z.; Yang, X. Effects of CO2 Application and Endophytic Bacterial Inoculation on Morphological Properties, Photosynthetic Characteristics and Cadmium Uptake of Two Ecotypes of Sedum alfredii Hance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Ishimaru, Y.; Shimo, H.; Bashir, K.; Senoura, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Ono, K.; Suzui, N.; Kawachi, N.; Ishii, S.; et al. From Laboratory to Field: OsNRAMP5-Knockdown Rice Is a Promising Candidate for Cd Phytoremediation in Paddy Fields. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.H. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, L.; Tian, S.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Zhou, W.; Lin, X. Cadmium-Induced Nitric Oxide Burst Enhances Cd Tolerance at Early Stage in Roots of a Hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Partially by Altering Glutathione Metabolism. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2761–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Phytoremediation of Microplastics: A Perspective on Its Practicality. Ind. Domest. Waste Manag. 2023, 3, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Ren, C.; Palansooriya, K.N.; Wang, Z.; Chang, S.X. Microplastic Pollution: Phytotoxicity, Environmental Risks, and Phytoremediation Strategies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Y.; Liu, T.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.J. Synthesis and Application of Coumarin Fluorescence Probes. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 10826–10847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tympa, L.E.; Katsara, K.; Moschou, P.N.; Kenanakis, G.; Papadakis, V.M. Do Microplastics Enter Our Food Chain via Root Vegetables? A Raman Based Spectroscopic Study on Raphanus sativus. Materials 2021, 14, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, J.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Tu, C. Quantitative Tracing of Uptake and Transport of Submicrometre Plastics in Crop Plants Using Lanthanide Chelates as a Dual-Functional Tracer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrano, D.M.; Wick, P.; Nowack, B. Placing Nanoplastics in the Context of Global Plastic Pollution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalčíková, G.; Žgajnar Gotvajn, A.; Kladnik, A.; Jemec, A. Impact of Polyethylene Microbeads on the Floating Freshwater Plant Duckweed Lemna Minor. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 230, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, G. Bio-Effects of Bio-Based and Fossil-Based Microplastics: Case Study with Lettuce-Soil System. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Saad, M.; Renault, N.; Tassin, B. Microplastic Contamination in an Urban Area: A Case Study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Christie, P.; Zhang, S. Uptake, Translocation, and Transformation of Metal-Based Nanoparticles in Plants: Recent Advances and Methodological Challenges. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziourrou, P. Study of the Formation of Microplastics, the Development and the Characteristics of Biofilm on Plastic Debris and the Interaction of Micro and Macroplastics with an Organic Pollutant in the Absence and Presence of Biofilm in the Coastal Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Patras, Patras, Greece, 2021. Available online: https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/50555?Locale=en (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Enfrin, M.; Lee, J.; Gibert, Y.; Basheer, F.; Kong, L.; Dumée, L.F. Release of Hazardous Nanoplastic Contaminants Due to Microplastics Fragmentation under Shear Stress Forces. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, R.; Zhou, J.; Wang, G. The Distribution and Impact of Polystyrene Nanoplastics on Cucumber Plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 16042–16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissanayake, P.D.; Kim, S.; Sarkar, B.; Oleszczuk, P.; Sang, M.K.; Haque, M.N.; Ahn, J.H.; Bank, M.S.; Ok, Y.S. Effects of Microplastics on the Terrestrial Environment: A Critical Review. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Bao, Q.; Gao, M.; Qiu, W.; Song, Z. A Novel Mechanism Study of Microplastic and As Co-Contamination on Indica Rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Tanveer, M.; Huang, L. Microplastic Stress in Plants: Effects on Plant Growth and Their Remediations. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1226484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewwandi, M.; Wijesekara, H.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Soysa, S.; Vithanage, M. Microplastics and Plastics-Associated Contaminants in Food and Beverages; Global Trends, Concentrations, and Human Exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, C.; Chadwick, D.; Jones, D.L.; Liu, E.; Liu, Q.; Bai, R.; He, W. Kinetics of Microplastic Generation from Different Types of Mulch Films in Agricultural Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, G.; Santal, A.R.; Singh, N.P. Omics Approaches in Effective Selection and Generation of Potential Plants for Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal from Contaminated Resources. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bolan, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Petruzzelli, G.; Pedron, F.; Franchi, E.; Fonseka, W.; Wijesekara, H.; Wang, L.; Hou, D.; et al. Role of Organic and Biochar Amendments on Enhanced Bioremediation of Soils Contaminated with Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2025, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.; Biczak, R. Phytoremediation and Environmental Law: Harnessing Biomass and Microbes to Restore Soils and Advance Biofuel Innovation. Energies 2025, 18, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Raj, D. Sources, Distribution, and Impacts of Emerging Contaminants–a Critical Review on Contamination of Landfill Leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryal, M. Phytoremediation Strategies for Mitigating Environmental Toxicants. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Xu, E.G.; Shabaka, S.; Chen, P.; Yang, Y. The Power of Green: Harnessing Phytoremediation to Combat Micro/Nanoplastics. Eco-Environ. Health 2024, 3, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Luan, Y.; Dai, W. Adsorption Behavior of Organic Pollutants on Microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ma, X.; Song, Y.; Zuo, S.; Li, H.; Deng, W. A Critical Review on the Interactions of Microplastics with Heavy Metals: Mechanism and Their Combined Effect on Organisms and Humans. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Gong, H.; Yan, M. Biological Degradation of Plastics and Microplastics: A Recent Perspective on Associated Mechanisms and Influencing Factors. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Chao, J.; Teng, J.; Wang, Q. Microplastics in Soils: A Review of Possible Sources, Analytical Methods and Ecological Impacts. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2052–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Zhou, T.; Wen, C.; Yan, C. The Effects of Microplastics on Heavy Metals Bioavailability in Soils: A Meta-Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lin, L.; Lin, Z.; Deng, X.; Li, W.; He, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Lei, Z.; et al. Influencing Mechanisms of Microplastics Existence on Soil Heavy Metals Accumulated by Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekersi, N.; Kadi, K.; Casini, S.; Addad, D.; Bazri, K.E.; Marref, S.E.; Lekmine, S.; Amari, A. Effects of Single and Combined Olive Mill Wastewater and Olive Mill Pomace on the Growth, Reproduction, and Survival of Two Earthworm Species (Aporrectodea trapezoides, Eisenia fetida). Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, L.D. Environmental Soil Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 9780126564464. [Google Scholar]

- Alkorta, I.; Garbisu, C. Phytoremediation of Organic Contaminants in Soils. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 79, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, A.M.; Sims, R.C.; Bugbee, B. Hycrest Crested Wheatgrass Accelerates the Degradation of Pentachlorophenol in Soil. J. Environ. Qual. 1994, 23, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meagher, R.B. Phytoremediation of Toxic Elemental and Organic Pollutants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 153–162, Erratum in Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarla, D.N.; Erickson, L.E.; Hettiarachchi, G.M.; Amadi, S.I.; Galkaduwa, M.; Davis, L.C.; Nurzhanova, A.; Pidlisnyuk, V. Phytoremediation and Bioremediation of Pesticide-Contaminated Soil. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Li, Y.; Hu, Q.N.; Zhang, L.; Mao, L.G.; Zhu, L.Z.; Jiang, H.Y.; Liu, X.G.; Sun, Y. Factors Impacting the Behavior of Phytoremediation in Pesticide-Contaminated Environment: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.N.; Basto, M.C.P.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Brix, H. A Review of Plant–Pharmaceutical Interactions: From Uptake and Effects in Crop Plants to Phytoremediation in Constructed Wetlands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 11729–11763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriot, N.; Zornoza, R.; Lwanga, E.H.; Zomer, P.; van Schothorst, B.; Ozbolat, O.; Lloret, E.; Ortega, R.; Miralles, I.; Harkes, P.; et al. Intensive Vegetable Production under Plastic Mulch: A Field Study on Soil Plastic and Pesticide Residues and Their Effects on the Soil Microbiome. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Zhang, S.; Huang, H.; Wu, T. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphorus Esters in Soils and Wheat Plants in a Plastic Waste Treatment Area in China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y. Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics on Uptake and Toxicity of Phenanthrene in Soybean. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 147016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, J.; Guo, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W. Effects of Microplastics on 3,5-Dichloroaniline Adsorption, Degradation, Bioaccumulation and Phytotoxicity in Soil-Chive Systems. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yang, G.; Zheng, Y. Effects of Microplastics, Fertilization and Pesticides on Alien and Native Plants. Plants 2024, 13, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Dong, Y.; Song, Z. Effect of Polystyrene on Di-Butyl Phthalate (DBP) Bioavailability and DBP-Induced Phytotoxicity in Lettuce. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, N.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhu, L. Effects of Biodegradable Plastic Film Mulching on the Global Warming Potential, Carbon Footprint, and Economic Benefits of Garlic Production. Agronomy 2024, 14, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Yang, X.; Tang, D.; Osman, R.; Geissen, V. Pesticide Bioaccumulation in Radish Produced from Soil Contaminated with Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 910, 168395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, E.; Guo, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, D.; Wang, H.; Ye, Q.; Yang, Z. Effects of Charged Polystyrene Microplastics on the Bioavailability of Dufulin in Tomato Plant. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.N.; Sampaio, M.J.; Tavares, P.B.; Silva, A.M.T.; Pereira, M.F.R. Aging Assessment of Microplastics (LDPE, PET and UPVC) under Urban Environment Stressors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B. PET-Microplastics as a Vector for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in a Simulated Plant Rhizosphere Zone. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101370, Erratum in Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhan, X. The Joint Toxicity of Polyethylene Microplastic and Phenanthrene to Wheat Seedlings. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 130967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Ji, J.; Guan, C. The Role of Microplastics in the Process of Laccase-Assisted Phytoremediation of Phenanthrene-Contaminated Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ma, L.Y.; Chen, X.; Ge, J.; Ma, Y.; Ji, R.; Yu, X. Insights into the Accumulation, Distribution and Toxicity of Pyrene Associated with Microplastics in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Seedlings. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 136988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wen, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zang, H.; Jones, D.L. Simazine Degradation in Agroecosystems: Will It Be Affected by the Type and Amount of Microplastic Pollution? Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Mercury. In Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Chapter 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780429192036. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, M.S. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability. Choice Rev. Online 2013, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Their Toxicological Effects on Humans. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. Mol. Clin. Environ. Toxicol. 2012, 101, 133–164. [Google Scholar]

- Eissa, F.; Elhawat, N.; Alshaal, T. Comparative Study between the Top Six Heavy Metals Involved in the EU RASFF Notifications over the Last 23 Years. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 265, 115489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, Mechanism and Health Effects of Some Heavy Metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, W.; Song, W.; Guo, M. Remediation Techniques for Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils: Principles and Applicability. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources, Chemistry, Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals-Concepts and Applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilon-Smits, E. Phytoremediation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, D.E.; Smith, R.D.; Raskin, I. Phytoremediation. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 49, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbafieri, M.; Pedron, F.; Petruzzelli, G.; Rosellini, I.; Franchi, E.; Bagatin, R.; Vocciante, M. Assisted Phytoremediation of a Multi-Contaminated Soil: Investigation on Arsenic and Lead Combined Mobilization and Removal. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides, B.J.; Drohan, P.J.; Spargo, J.T.; Maximova, S.N.; Guiltinan, M.J.; Miller, D.A. Cadmium Phytoextraction by Helianthus annuus (Sunflower), Brassica napus Cv Wichita (Rapeseed), and Chyrsopogon zizanioides (Vetiver). Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Singh, S.P. A Review on Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals and Utilization of Its Byproducts. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2005, 6, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Rascio, N.; Navari-Izzo, F. Heavy Metal Hyperaccumulating Plants: How and Why Do They Do It? And What Makes Them so Interesting? Plant Sci. 2011, 180, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, M.; Sandhya, S.; Prasad, M.N.V.; Freitas, H. Perspectives of Plant-Associated Microbes in Heavy Metal Phytoremediation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 1562–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Siraj, M.; Zaman, W. Molecular Communication of Microbial Plant Biostimulants in the Rhizosphere Under Abiotic Stress Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wu, D.; Yu, Y.; Han, S.; Sun, L.; Li, M. Impact of Microplastics on Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in Rape (Brassica napus L.). Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Lin, X.; Yu, Y. Different Effects and Mechanisms of Polystyrene Micro- and Nano-Plastics on the Uptake of Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd) by Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, W.; Li, W.; Xu, S.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, F. Effects of Microplastics on Cadmium Accumulation by Rice and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Communities in Cadmium-Contaminated Soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, L.; Boughattas, I.; Helaoui, S.; Mkhinini, M.; Jabnouni, H.; Ben Fadhl, E.; Alphonse, V.; Livet, A.; Giusti-Miller, S.; Banni, M.; et al. Environmental Microplastic Interact with Heavy Metal in Polluted Soil from Mine Site in the North of Tunisia: Effects on Heavy Metal Accumulation, Growth, Photosynthetic Activities, and Biochemical Responses of Alfalfa Plants (Medicago saliva L.). Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Qin, X.; Lan, W.; Shi, D.; Tang, Y.; Yu, F.; Li, Y. Potential Impacts of Polyethylene Microplastics and Heavy Metals on Bidens pilosa L. Growth: Shifts in Root-Associated Endophyte Microbial Communities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jędruchniewicz, K.; Bogusz, A.; Chańko, M.; Bank, M.S.; Alessi, D.S.; Ok, Y.S.; Oleszczuk, P. Extractability and Phytotoxicity of Heavy Metals and Essential Elements from Plastics in Soil Solutions and Root Exudates. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 166100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, J.; Su, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhang, J. Impacts of Conventional and Biodegradable Microplastics in Maize-Soil Ecosystems: Above and below Ground. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Shen, C.; Wang, L.; Xu, M. Exploration of Single and Co-Toxic Effects of Polypropylene Micro-Plastics and Cadmium on Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirin, J.; Chen, Y.; Hussain Shah, A.; Da, Y.; Zhou, G.; Sun, Q. Micro Plastic Driving Changes in the Soil Microbes and Lettuce Growth under the Influence of Heavy Metals Contaminated Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1427166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Poblete, A.; Retamal-Salgado, J.; López, M.D.; Zapata, N.; Sierra-Almeida, A.; Schoebitz, M. Combined Effect of Microplastics and Cd Alters the Enzymatic Activity of Soil and the Productivity of Strawberry Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Osman, R.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, M. Analyzing the Impacts of Cadmium Alone and in Co-Existence with Polypropylene Microplastics on Wheat Growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1240472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xie, W.; Dai, H.; Wei, S.; Skuza, L.; Li, J.; Shi, C.; Zhang, L. Effects of Combined Microplastics and Heavy Metals Pollution on Terrestrial Plants and Rhizosphere Environment: A Review. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wei, Y.; Yang, C.; He, Z. Interactions of Microplastics and Soil Pollutants in Soil-Plant Systems. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Carter, L.J.; Banwart, S.A.; Kay, P. Microplastics in Soil–Plant Systems: Current Knowledge, Research Gaps, and Future Directions for Agricultural Sustainability. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, B.; Medyńska-Juraszek, A. Microplastic-Mediated Heavy Metal Uptake in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.): Implications for Food Safety and Agricultural Sustainability. Molecules 2025, 30, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, S.; Qiu, T.; Cui, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Huang, M.; Zhan, A.; Fang, L. Interaction of Microplastics with Heavy Metals in Soil: Mechanisms, Influencing Factors and Biological Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajal, S.; Thakur, S. Coexistence of Microplastics and Heavy Metals in Soil: Occurrence, Transport, Key Interactions and Effect on Plants. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Y.; Wang, M.; Shi, J.-W.; Li, B.L.; Liu, L.; Duan, P.-F.; Chen, Z.-J. The Effects of Microplastics and Heavy Metals Individually and in Combination on the Growth of Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatic) and Rhizosphere Microorganisms. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, H.D.; Shah, G.; Bhatt, U.; Singh, H.; Soni, V. Microplastics and Plant Health: A Comprehensive Review of Sources, Distribution, Toxicity, and Remediation. Npj Emerg. Contam. 2025, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Debele, S.E.; Sahani, J.; Rawat, N.; Marti-Cardona, B.; Alfieri, S.M.; Basu, B.; Basu, A.S.; Bowyer, P.; Charizopoulos, N.; et al. An Overview of Monitoring Methods for Assessing the Performance of Nature-Based Solutions against Natural Hazards. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.N.; Lado Ribeiro, A.R.; Silva, A.M.T.; Pereira, M.F.R. Can Aged Microplastics Be Transport Vectors for Organic Micropollutants?–Sorption and Phytotoxicity Tests. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 158073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, L.; Huang, H.; Ye, K.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, L.; et al. Analysis of Aged Microplastics: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1861–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parus, A.; Lisiecka, N.; Kloziński, A.; Zembrzuska, J. Do Microplastics in Soil Influence the Bioavailability of Sulfamethoxazole to Plants? Plants 2025, 14, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Masset, T.; Breider, F. Adsorption of Copper by Naturally and Artificially Aged Polystyrene Microplastics and Subsequent Release in Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluid. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2024, 26, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Gui, X.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Cao, X. Contrasting Effects of Physical and Chemical Aging of Microplastics on the Transport of Lead and Copper in Sandy Soil. Environ. Res. 2025, 286, 122991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, H.; Yang, X.; Osman, R.; Geissen, V. The Role of Microplastic Aging on Chlorpyrifos Adsorption-Desorption and Microplastic Bioconcentration. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 331, 121910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Y.; Hou, Q.; Long, M.; Wang, Z.; Rillig, M.C.; Liao, Y.; Yong, T. Soil Microbial Community Parameters Affected by Microplastics and Other Plastic Residues. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1258606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Niu, X.; Wang, X.; Min, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, X. The Sorption Behavior of Triclosan on Microplastics: Aging Effects and Mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 163985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais-Bergeron, B.; Paul, A.L.D.; Chagnon, P.L.; Baker, A.J.M.; van der Ent, A.; Faucon, M.P.; Quintela-Sabarís, C.; Labrecque, M. Trace Element Hyperaccumulator Plant Traits: A Call for Trait Data Collection. Plant Soil 2023, 488, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, B.; Liu, X.; Xiao, H.; Liu, S.; Shao, H. Systematic Evaluation of Plant Metals/Metalloids Accumulation Efficiency: A Global Synthesis of Bioaccumulation and Translocation Factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1602951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, F.; Niederle, P.; Sinclar, F.; Carmona, N.E.; Gueneau, S.; Gitz, V.; Alpha, A.; Sabourin, E.; Hainzelin, E. Agroecologically-Conducive Policies: A Review of Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges; The Transformative Partnership Platform on Agroecology: Bogor, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X.; Lei, M.; Chen, T. Cost–Benefit Calculation of Phytoremediation Technology for Heavy-Metal-Contaminated Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563–564, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aghajani Delavar, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Phytoremediation: A Strategic Rethinking. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 165949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Feng, S.; Guan, Y. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis of Optimal Planting for Enhancing Phytoremediation of Trace Heavy Metals in Mining Sites under Interval Residual Contaminant Concentrations. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, M. Recent Advances in Pesticide Bioremediation: Integrating Microbial, Phytoremediation, and Biotechnological Strategies-a Comprehensive Review. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2025, 37, 2554173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharat, Z.; Novo, L.A.B.; Yasmin, A. Genome Editing Weds CRISPR: What Is in It for Phytoremediation? Plants 2018, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, N.; Hermans, C.; Schat, H. Molecular Mechanisms of Metal Hyperaccumulation in Plants. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 759–776, Erratum in New Phytol. 2009, 182, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, N.; Yu, Q. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Assisted Colonization of Synthetic Bacteria on Plant Roots for Improved Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalwani, A.; AL-Jaf, I.M.; Abed, B.; Latef, S.; Ahmed, M. Biosafety and Environmental Risks of Genetically Modified Plants. J. Univ. Anbar Pure Sci. 2024, 18, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, W.; Priyashantha, H.; Gajanayake, P.; Manage, P.; Liyanage, C.; Jayarathna, S.; Kumarasinghe, U. Review and Prospects of Phytoremediation: Harnessing Biofuel-Producing Plants for Environmental Remediation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-Y.; Cho, K.-S.; Yun, J. Phytoremediaton Strategies for Co-Contaminated Soils: Overcoming Challenges, Enhancing Efficiency, and Exploring Future Advancements and Innovations. Processes 2025, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.P. Nanophytoremediation: Advancing Phytoremediation Efficiency Through Nanotechnology Integration. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badamasi, H.; Aliyu Abdullahi, U.; Praveen Kumar, A.; Durumin Iya, N.I.; Varra, V.; Ademola Olaleye, A.; Falalu Hamza, M. Nanotechnology-Assisted Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils: A State-of-the-Art Review on Recent Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Chen, X.W.; Zhai, F.H.; Li, Y.T.; Zhao, H.M.; Mo, C.H.; Luo, Y.; Xing, B.; Li, H. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Alleviates Charged Nanoplastic Stress in Host Plants via Enhanced Defense-Related Gene Expressions and Hyphal Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6258–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xing, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Tang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, B. The Removal and Mitigation Effects of Biochar on Microplastics in Water and Soils: Application and Mechanism Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lin, X.; Xiao, Y. Integration of Smart Sensors and Phytoremediation for Real-Time Pollution Monitoring and Ecological Restoration in Agricultural Waste Management. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1550302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Shen, P.; Liang, H.; Wu, Q. Biochar Relieves the Toxic Effects of Microplastics on the Root-Rhizosphere Soil System by Altering Root Expression Profiles and Microbial Diversity and Functions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 115935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maceiras, R.; Perez-Rial, L.; Alfonsin, V.; Feijoo, J.; Lopez, I. Biochar Amendments and Phytoremediation: A Combined Approach for Effective Lead Removal in Shooting Range Soils. Toxics 2024, 12, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Saxena, N.; Sharma, D. Phytoremediation as a Green and Sustainable Prospective Method for Heavy Metal Contamination: A Review. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 1269–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, P.S.; Kudave, P.S.; Wani, A.K.; Yadav, T. Prospects of Phytoremediation in Degradation of Environmental Contaminants: Recent Advances, Challenges and Way Forward. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2025, 27, 1442–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, L.-Y.; Mingyuan, L.; Mohammadi, M.; Tee, C.-S.; Yuswan, M.H.; Cheng, W.-H.; Lai, K.-S. Phytoremediation as a Viable Ecological and Socioeconomic Management Strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 50126–50141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, E.; Doty, S. Social Acceptability of Phytoremediation: The Role of Risk and Values. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2016, 18, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beans, C. Phytoremediation Advances in the Lab but Lags in the Field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7475–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.M.; Phelan, T.J.; Smith, N.M.; Smits, K.M. Remediation in Developing Countries: A Review of Previously Implemented Projects and Analysis of Stakeholder Participation Efforts. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 1259–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorieva, E.; Livenets, A.; Stelmakh, E. Adaptation of Agriculture to Climate Change: A Scoping Review. Climate 2023, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.; Pereira, S.I.A.; Mench, M.; Garbisu, C.; Kidd, P.; Castro, P.M.L. Phytomanagement of Metal(Loid)-Contaminated Soils: Options, Efficiency and Value. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 661423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavi, S.; Anandaraja, N.; Murugan, P.P.; Latha, M.R.; Pangayar Selvi, R. Challenges and Strategies of Resource Poor Farmers in Adoption of Innovative Farming Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Agric. Syst. 2025, 227, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenning, P.; Norrman, J.; Weih, M.; Kleja, D.B. Phytomanagement of Contaminated Land to Produce Biofuels for the Maritime Sector; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Plastic | Concentration of Plastics | Dimensions of the Plastics | Soil pH | Other Characteristics of Soil | Plant | Organic Pollutants | Concentration of the Pollutants | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | 2 · 103 particles kg−1 and area of 60 cm2 kg−1 | >100 μm | Alkaline (7.8–9.1) | 0–10 cm depth, haplic calcisol (loamic, hyper calcic), soil organic carbon between 0.7% to 2.1% and the soil nitrogen between 0.7% to 1.9% Soil Texture (ST): Loamy Field experiment | Vegetables | 4–10 different pesticide residues in all soil samples: azoxystrobin, imidacloprid, chlorantraniliprole, boscalid, difenoconazole, chlorantraniliprole, cypermethrin, imidacloprid, oxyfluorfen, pendimethalin | 0.14 mg kg−1 | [104] |

| Plastic wastes | Farmland soil, 0–15 cm. Field experiment. | Wheat: Triticum aestivum L. | Organophosphate esters (OPEs) | Total concentrations of 0.038–1.25 mg kg−1 | [105] | |||

| Fluorescent PS | 10 mg kg−1 | 0.1 μm, 1 μm, 10 μm and 100 μm | 7.2 | SOM: 27.8 g kg−1, CEC: 21.6 cmol kg−1, TN: 1.79 g kg−1, TP: 0.82 g kg−1 Pot experiment | Glycine max L. Merrill | Phenanthrene | [106] | |

| PE and PLA | Four groups (3,5-DCA, MPs, MPs + 3,5-DCA, and control with no MPs or 3,5-DCA): 0.1%, 0.2%, and 2%, respectively | 50–100 μm | 7.41 | 0–20 cm, Organic matter: 29 g kg−1, Cation exchange capability 8.9 cmol+ kg−1 ST: Yellow loam soil Pot experiment | Chive: Allium ascalonicum | 3,5-dichloroaniline (3,5-DCA): a toxic metabolite of dicarboximide fungicides | 10 mg kg−1 | [107] |

| PE | 2% of the soil fresh weight | 150 μm | Field soil and sand together at 2:1 Pot experiment | 10 terrestrial plants (5 alien species: Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) R. M. King & H. Rob., Bidens pilosa L., Chromolaena odorata (L.) R. M. King & H. Rob., Phytolacca americana L. and Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A. Gray; and 5 native species: Coix lacryma-jobi L., Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H. Rob., Laggera crispata (Vahl) Hepper & J. R. I. Wood, Puhuaea sequax (Wall.) H. Ohashi & K. Ohashi and Senecio scandens Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don) | Indoxacarb | [108] | ||

| PS | Small PS (SPS): 100–1000 nm 0.1–1 μm and large PS (LPS) > 10 μm | Lettuce: Lactuca sativa L. var. ramosa Hort. | Di-butyl phthalate (DBP) | [109] | ||||

| Polyester | 0.03% and 7% | Microplastic fibers: Average length: 3300 μm Width: 100 μm | 6.88 | Ablend of peat moss, bark mulch, perlite, and an NPK fertilizer of 0.21%–0.11%–0.16%. Electrical Conductivity: 322.8 ± 24.5 μS cm−1 Pot experiment | Lactuca sativa | Naproxen | [110,111] | |

| Butylene adipate co-terephthalate (PBAT), LDPE and PLA | 20% w/w (85% of PBAT, LDPE & 10% of PLA) | Pellets: 200 to 500 μm | 6.95 | 83% sand, 11% silt and <1% clay with an organic matter content of 4%. ST: Sandy soil Ceramic pot experiment | Radish: Raphanus sativus | Pesticides (chlorpyrifos (CPF), difenoconazole (DIF) and their mixture) | 15 mg kg−1 | [111] |

| Three types of MPs-PS: carboxyl PS (PS-COO−), neutral PS (PS) and amino PS (PS-NH3+) | 0.2 μm | 7.0 | 0–20 cm depth, 12.0% clay, 20.6% silt, 67.4% sand, 29.3 g kg−1 organic matter ST: Silty loam | Cherry tomato: Lycopersicon esculentum | Antiviral pesticide Dufulin (DFL) | [112] | ||

| LDPE, PET, uPVC | LDPE (average particle diameter of 509 ± 221 μm), PET (161 ± 79 μm) and uPVC (159 ± 4 3 μm) | Lepidium sativum and Sinapis alba. | Pesticides (alachlor, clofibric acid, diuron, pentachlorophenol) | [113] | ||||

| PET | 1 g of MPs in 20 mL of both naphthalene and phenanthrene | 2000 μm | Rhizosphere soil | Wheat | Naphthalene and phenanthrene | Naphthalene 0.018 mg kg−1 & phenanthrene 0.00011 mg kg−1 | [114] | |

| PE | 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 8% w/w | 200–250 μm | 6.43 | Yellow brown, organic matter content: 2.04% Pot experiment (contained 500 g soils) | Wheat | Phenanthrene | 100 mg kg−1 | [115] |

| PE | 2% w/w | 550 μm | Farmland soils Field experiment (greenhouse) | Zea mays L. | Phenanthrene | 150 mg kg−1 | [116] | |

| PE | 20 mg L−1 | 50–100 μm | Rhizosphere soil in hydroponic conditions. Field experiment | Oryza sativa L. | 14C-pyrene | [117] | ||

| PE, PLA | 2% | 50–100 µm | 7.41 | 0–20 cm depth, Organic matter: 29.0 g kg−1, Cation exchange capability: 8.96 cmol+ kg−1 Pot experiment | Allium ascalonicum | 3,5-dichloroaniline (3,5-DCA) | 10 mg kg−1 | [107] |

| PE, PVC | 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% by soil dry weight | <125 μm | 5.7 | 0–20 cm depth, organic C content: 3.5%, total N: 0.26% ST: Silty clay loam Pot experiment | Wheat: Triticum aestivum L. | Herbicide (simazine) | 1%, 5%, 10% and 20% of soil w/w | [118] |

| Type of Plastic | Concentration of Plastics | Dimensions of the Plastics | Soil pH | Other Characteristics of Soil | Sampling Area | Plant | Inorganic Pollutants | Concentration of the Pollutants | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 2.5% and 5% w/w | <5000 μm | Alkaline soil | Soil Texture (ST): Clay Loam | Rural and urban | Lettuce | Cd and Zn | [17] | |

| PE | 0.001%, 0.01%, or 0.1% PE-MPs | Average size: 293 μm | 7.38 | Organic matter content of 2.39%, total nitrogen (N) content of 1.03 g kg−1, total phosphorus (P) content of 0.56 g kg−1 | Northeast Forestry University (Harbin, China) | Brassica napus L. | Cu2+ and Pb2+ | Cu2+: 50 and 100 mg/kg, Pb2+: 25 and 50 mg kg−1 | [137] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | 100 and 1000 mg kg−1 | MPs (PS-MPs) and NPs (PS-NPs) | 6.3 | SOM: 35.3 g kg−1, TN: 4.1 g kg−1, TP: 2.9 g kg−1 | A vegetable field in Liaoyuan, China, characterized by the long-term use of organic fertilizer | Lettuce: Lactuca sativa L. | Cu, Zn and Pb, Cd | The concentrations of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd in the soil are measured at 82.00, 174.84, 42.08, and 0.20 mg kg−1, respectively | [138] |

| Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polylactic acid (PLA), and polyester (PES) | 3 doses (0, 0.2%, and 2%, w/w) of PET and PLA, and 2 doses (0% and 0.2%) of PES | PET, PLA: average particle size ~51 µm; Fibrous PES: average length of 6000–10,000 μm and an average diameter of 10–25 µm | 5.63 | 0–30 cm depth, NH4+-N 1.71 mg kg−1, NO3−-N 40.2 mg kg−1, available P 9.82 mg kg−1, available K 53.6 mg kg−1, organic matter 11.8 g kg−1, Cd 0.03 mg kg−1 | Nanquan Town, Jimo District, Qingdao, Shandong Province, China | Rice | Cd | 0 and 5 mg Cd kg−1 soil | [139] |

| Polypropylene (PP), polyamide (PA), polyethylene (PE), Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyethylene vinyl acetate (PEVA) | D1 = 1 mg kg−1 of soil and D2 = 100 mg kg−1 of soil. | Per 1 mg of plastic powder, MPs size distribution was 15.23% > 3 μm, 35.56% 3 μm–1.2 μm and 49.21% 1.2 μm–0.45 μm. | 0–15 cm depth | Jebel Ressass mine, north Tunisia | Medicago sativa | Cu, Zn, Pb, Cd and Ni. | [140] | ||

| PE | 1.2 kg of soil in each pot: 2 g of 0.5 μm PE, 4 g of 0.5 μm PE, 2 g of 1 μm PE, and 4 g of 1 μm PE | 0.5 μm and 1.0 μm | Restoration area of the Siding Pb-Zn mine in Liuzhou, China | Bidens pilosa L. | Cd and Pb | [141] | |||

| LDPE, PET and PP | 1 × 1 cm squares (mesoplastics) | 0–20 cm depth | Przychody, Jelnica and Dąbrowa Górnicza in Polland | Lepidium sativum | Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Na, Ni, Pb, and Zn | [142] | |||

| PLA and PP | 1% MPs (PP2/PLA2, mass/mass) and 5% MPs (PP3/PLA3, mass/mass) across three different levels of Cd | The material was filtered using a 500 μm mesh | 7.23, 7.22 and 7.18 | 0–20 cm depth. Cation exchange capacity (CEC): 20.7, 21.0, and 22.3 c mol kg−1 Dissolved organic carbon (DOC): 1.69, 1.57, and 1.45 g kg−1 | Qingdao, northern China | Pak choi | Cd | The total Cd in the sampled soils were 0.49, 2.52, and 10.1 mg kg−1 | [143] |

| PP | 100 mg L−1 | 6.5 and 13 µm | Petri plates experiment | Oryza sativa L. seeds | Cd | Cd-5 mg kg−1, 13 µm PP100 mg kg−1, 6.5 µm PP- 100 mg kg−1, 13 µm PP + Cd- 100 mg kg−1 + 5 mg kg−1, 6.5 µm PP + Cd100 mg kg−1 + 5 mg kg−1 in Petri plates | [144] | ||

| PS | 1.4 g kg−1 soil | T1 = 106 µm, T2 = 50 µm, and T3 = 13 µm | Highest value (T3): 7.79; Lowest value (for day 0): 7.37 | Day 0: EC (µS cm−1): 763.6, OM (%): 1.01, TP (mg kg−1): 104.42, TN (mg/kg): 449.33, NH3 (mg kg−1): 2.5. Pot experiment | Tongling, central part of Anhui Province, Southeast China | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | HMs: Cd, As, Cu, Zn, Pb | [145] | |

| HDPE (Carbon black + uv additive) | 0.2 g kg−1 | 2000–5000 μm and 20 µm thick | 5.61 | Volcanic ash-derived soil (Andisol); Soil–sand; 1:1 = Vol:Vol. 82.2 mg kg−1 of available nitrogen, 47.6 mg kg−1 of available Olsen P, 220.6 mg kg−1 of available potassium, 17 cmolc kg of exchangeable Ca, 3 cmolc kg−1 of exchangeable Mg, 3.41% organic matter. Experiment: Clay pots | The plants came from Llahuen Nursery, Llahuen Farm in Huelquen Paine, Metropolitan Region, Chile | Strawberry plants (Fragaria x ananassa Duch) | Cd | 0.5 mg kg−1 | [146] |

| PP | 50 and 100 µm | Agricultural soil | Wheat | Cd | 40 mg kg−1 | [147] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tziourrou, P.; Golia, E.E. Phytoremediation of Co-Contaminated Environments: A Review of Microplastic and Heavy Metal/Organic Pollutant Interactions and Plant-Based Removal Approaches. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040137

Tziourrou P, Golia EE. Phytoremediation of Co-Contaminated Environments: A Review of Microplastic and Heavy Metal/Organic Pollutant Interactions and Plant-Based Removal Approaches. Soil Systems. 2025; 9(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040137

Chicago/Turabian StyleTziourrou, Pavlos, and Evangelia E. Golia. 2025. "Phytoremediation of Co-Contaminated Environments: A Review of Microplastic and Heavy Metal/Organic Pollutant Interactions and Plant-Based Removal Approaches" Soil Systems 9, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040137

APA StyleTziourrou, P., & Golia, E. E. (2025). Phytoremediation of Co-Contaminated Environments: A Review of Microplastic and Heavy Metal/Organic Pollutant Interactions and Plant-Based Removal Approaches. Soil Systems, 9(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040137