Fingerprinting of Bulk and Water-Extractable Soil Organic Matter of Chernozems Under Different Tillage Practices for Twelve Years: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Sampling

2.2. Methods

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of the Soils Under Different Tillage Practices

3.2. SOM Composition Features of the Soils Under Different Tillage Treatments

3.2.1. FTIR (DRIFTS Mode)

3.2.2. Pyrolysis GC/MS

3.3. WEOM Composition Features of the Soils Under Different Treatments

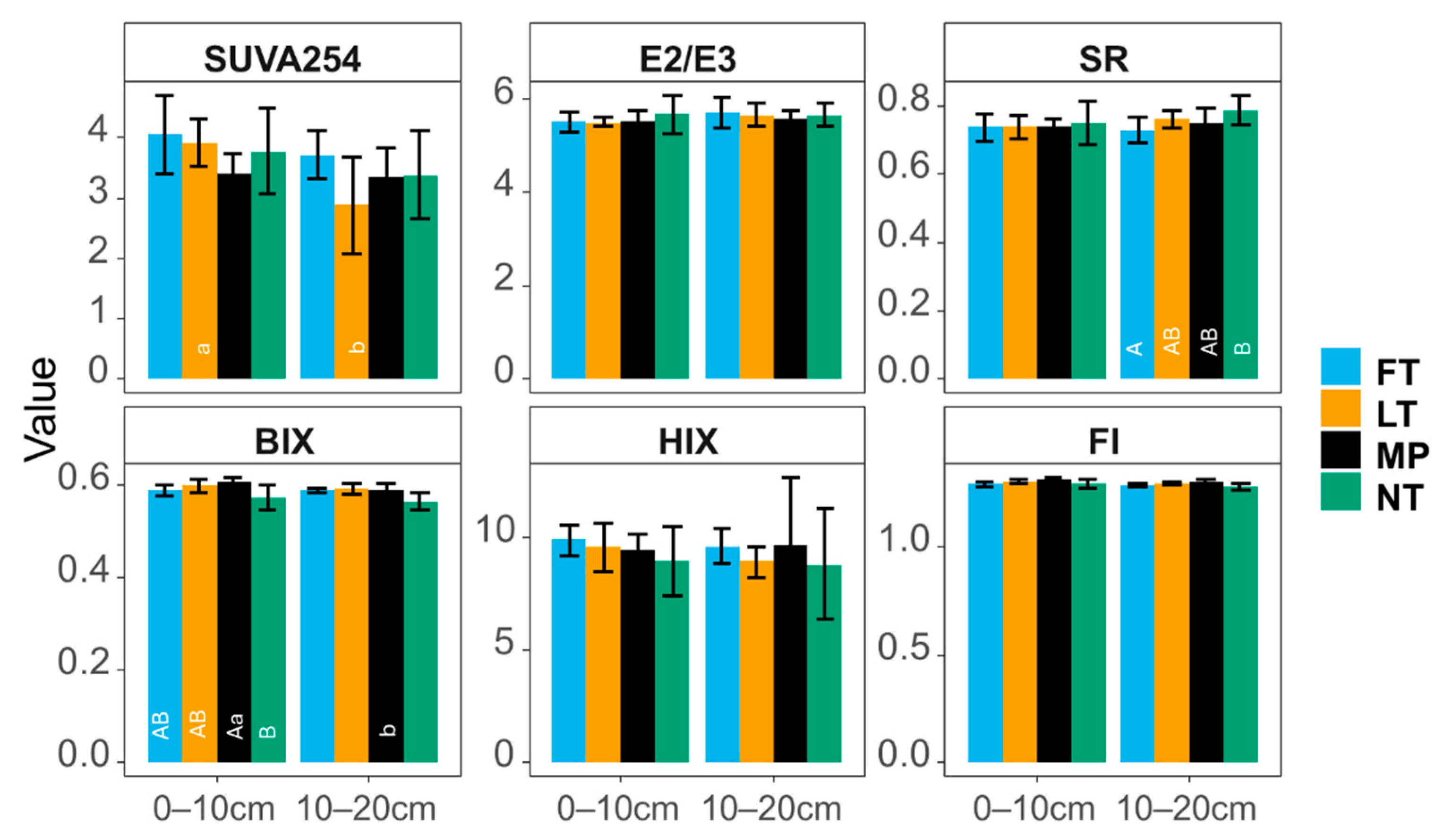

3.3.1. Optical Indices

3.3.2. Individual Fluorescent Components

3.3.3. FTIR (Transmission Mode)

3.4. Relationships Between Soil Physical Properties and SOM Composition Characteristics

Correlation of Physical Properties with Chemical Characteristics, FTIR Spectroscopy, and Analytical Pyrolysis Data in Chernozems

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Tillage Practices on the Structure and Main Chemical Characteristics of Soils

4.2. Bulk SOM Composition as Affected by Tillage Treatment

4.2.1. SOM Variations Assessed by FTIR-DRIFTS

4.2.2. Pyrolytic Fingerprinting of SOM Variations

The 0–10 cm Layer

The 10–20 cm Layer

4.3. WEOM Composition as Affected by Tillage Treatments

4.3.1. WEOM Variations Assessed by UV–Vis Spectrometry and Spectrofluorometry

WEOM Optical Indices

Individual Fluorescent Components

4.3.2. WEOM Variations Assessed by FTIR

4.4. Linking Soil Physical Properties to Chernozem Organic Matter Composition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haddaway, N.R.; Hedlund, K.; Jackson, L.E.; Kätterer, T.; Lugato, E.; Thomsen, I.K.; Jørgensen, H.B.; Isberg, P.-E. How does tillage intensity affect soil organic carbon? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 2017, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.F.; Reicosky, D.C.; Allmaras, R.R.; Sauer, T.J.; Venterea, R.T.; Dell, C.J. Greenhouse gas contributions and mitigation potential of agriculture in the central USA. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 83, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.O.; Post, W.M. Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rates by Tillage and Crop Rotation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 1930–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Lal, R. Principles of Soil Conservation and Management; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karlen, D.; Cambardella, C. Conservation strategies for improving soil quality and organic matter storage. In Structure and Organic Matter Storage in Agricultural Soils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. The Role of Residues Management in Sustainable Agricultural Systems. J. Sustain. Agric. 1995, 5, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balesdent, J.; Chenu, C.; Balabane, M. Relationship of soil organic matter dynamics to physical protection and tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2000, 53, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeler, E.; Tscherko, D.; Spiegel, H. Long-term monitoring of microbial biomass, N mineralisation and enzyme activities of a Chernozem under different tillage management. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1999, 28, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoncini, M.; Antichi, D.; Di Bene, C.; Risaliti, R.; Petri, M.; Bonari, E. Soil carbon and nitrogen changes after 28 years of no-tillage management under Mediterranean conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 77, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, S.M.; Alsaker, C.; Baldock, J.; Bernoux, M.; Breidt, F.J.; McConkey, B.; Regina, K.; Vazquez-Amabile, G.G. Climate and Soil Characteristics Determine Where No-Till Management Can Store Carbon in Soils and Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimon, T.; Javůrek, M.; Mikanová, O.; Vach, M. The influence of tillage systems on soil organic matter and soil hydrophobicity. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 105, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, A.; Remelli, S.; Boselli, R.; Mantovi, P.; Ardenti, F.; Trevisan, M.; Menta, C.; Tabaglio, V. Driving crop yield, soil organic C pools, and soil biodiversity with selected winter cover crops under no-till. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 217, 105283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, A.; Bruland, G. Comparison of Soil Properties between Paired No-till and Conventional Tillage Systems in Central Illinois. Trans. Ill. State Acad. Sci. 2020, 113, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, T.B.; Mazzoncini, M.; Bàrberi, P.; Antichi, D.; Silvestri, N. Fifteen years of no till increase soil organic matter, microbial biomass and arthropod diversity in cover crop-based arable cropping systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.A.; Titmarsh, G.W.; Freebairn, D.M.; Radford, B.J. No-tillage and conservation farming practices in grain growing areas of Queensland a review of 40 years of development. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2007, 47, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlen, D.L.; Cambardella, C.A.; Kovar, J.L.; Colvin, T.S. Soil quality response to long-term tillage and crop rotation practices. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 133, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeler, E.; Böhm, K.E. Temporal dynamics of microbial biomass, xylanase activity, N-mineralisation and potential nitrification in different tillage systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1996, 4, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.R.; Weil, R. Soil quality indicator properties in mid-Atlantic soils as influenced by conservation management. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2000, 55, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M. The environmental consequences of adopting conservation tillage in Europe: Reviewing the evidence. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 103, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Nierop, K.G.J.; Rietkerk, M.; Dekker, S.C. Predicting soil water repellency using hydrophobic organic compounds and their vegetation origin. Soil 2015, 1, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, G.; Mueller, K.E.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Freeman, K.H.; Mueller, C.W. Aggregation controls the stability of lignin and lipids in clay-sized particulate and mineral associated organic matter. Biogeochemistry 2017, 132, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.C.; Incerti, G.; Spaccini, R.; Piccolo, A.; Mazzoleni, S.; Bonanomi, G. Linking organic matter chemistry with soil aggregate stability: Insight from 13C NMR spectroscopy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsri, K.; Watanabe, A. Insights into the formation and stability of soil aggregates in relation to the structural properties of dissolved organic matter from various organic amendments. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 232, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Yao, S.; Zhu, S.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Su, X.; Huang, R.; Yin, Y.; Lv, J.; Jiang, T.; et al. Evaluating soil dissolved organic matter as a proxy for soil organic matter properties across diverse ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 204, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, F.; Sang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Miao, A. Decipher the Persistence of Soil Dissolved Organic Matter Under Different Land Use Types Using Potential Molecular Transformations. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Koal, P.; Gerl, G.; Schroll, R.; Joergensen, R.G.; Munch, J.C. Water-extractable organic matter and its fluorescence fractions in response to minimum tillage and organic farming in a Cambisol. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Angelini, M.E.; Yigini, Y.; Luotto, I. Global black soil distribution. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkin, A.P.; Fomicheva, D.V.; Shamshurina, E.N.; Zazdravnukh, E.A.; Rukhovich, D.I.; Fang, H.Y. Digital soil mapping of erosion-induced degradation of Chernozems on the East-European Plain. Geoderma Reg. 2025, 41, e00953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkin, A.P.; Khirk, A.V.; Shchepotiev, V.N.; Fomicheva, D.V.; Zhuikov, D.V. Erosion Control Measures on Agricultural Land in Russia: A Review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2024, 57, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Müller, C.; Cai, Z. Effects of long-term no tillage treatment on gross soil N transformations in black soil in Northeast China. Geoderma 2017, 301, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisover, M.; Lordian, A.; Levy, G.J. Water-extractable soil organic matter characterization by chromophoric indicators: Effects of soil type and irrigation water quality. Geoderma 2012, 179–180, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coble, P.G.; Lead, J.; Baker, A. Aquatic Organic Matter Fluorescence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Danilin, I.V.; Danchenko, N.N.; Ziganshina, A.R.; Farkhodov, Y.R.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Kholodov, V.A. Divergent response of Chernozem organic matter towards short-term water stress in Poa pratensis L. rhizosphere and bulk soil in pot experiments: A spectroscopic study. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 245, 106285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodov, V.A.; Danchenko, N.N.; Ziganshina, A.R.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Semiletov, I.P. Direct Salinity Effect on Absorbance and Fluorescence of Chernozem Water-Extractable Organic Matter. Aquat. Geochem. 2024, 30, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Laor, Y.; Raviv, M.; Medina, S.; Saadi, I.; Krasnovsky, A.; Vager, M.; Levy, G.J.; Bar-Tal, A.; Borisover, M. Compositional characteristics of organic matter and its water-extractable components across a profile of organically managed soil. Geoderma 2017, 286, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S.K.L.; Boyer, T.H. Behavior of Reoccurring PARAFAC Components in Fluorescent Dissolved Organic Matter in Natural and Engineered Systems: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasonova, A.; Levy, G.J.; Rinot, O.; Eshel, G.; Borisover, M. Organic matter in aqueous soil extracts: Prediction of compositional attributes from bulk soil mid-IR spectra using partial least square regressions. Geoderma 2022, 411, 115678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, L.; Gaistardo, C.; Deckers, J.; Dondeyne, S.; Eberhardt, E.; Gerasimova, M.; Harms, B.; Jones, A.; Krasilnikov, P.; Reinsch, T.; et al. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- Semenikhina, Y.; Kambulov, S.; Pakhomov, V. Peculiarities of tillage in the conditions of dry farming in the cultivation of soybeans. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 413, 01018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, N.V.; Milanovskii, E.Y.; Rogova, O.B. Method of preparing soil samples for determining the contact angle of wetting by a sessile drop method. Byulleten Pochvennogo Instituta Im. V.V. Dokuchaeva 2019, 97, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodov, V.; Yaroslavtseva, N.; Farkhodov, Y.; Belobrov, V.; Yudin, S.; Aydiev, A.; Lazarev, V.; Frid, A. Changes in the Ratio of Aggregate Fractions in Humus Horizons of Chernozems in Response to the Type of Their Use. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shein, E.V. A Course of Soil Physics; Izd. Mosk. Gos. Univ: Moscow, Russia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- GOST 26423-85; Soils. Methods for Determining Specific Electrical Conductivity, pH, and Dry Residue of Aqueous Extract. USSR Gosstandart: Moscow, Russia, 1986.

- GOST 26483-85; Soils. Preparation of Salt Extract and Determination of Its pH by the TSINAO Method. USSR Gosstandart: Moscow, Russia, 1986.

- GOST 26205-91; Soils. Determination of Mobile Compounds of Phosphorus and Potassium by Machigin Method Modified by CINAO. USSR Gosstandart: Moscow, Russia, 1991.

- ISO 10694:1995; Soil Quality—Determination of Organic and Total Carbon After Dry Combustion (Elementary Analysis). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- Pansu, M.; Gautheyrou, J. Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8245; Water Quality—Guidelines for the Determination of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) and Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Helms, J.R.; Stubbins, A.; Ritchie, J.D.; Minor, E.C.; Kieber, D.J.; Mopper, K. Absorption spectral slopes and slope ratios as indicators of molecular weight, source, and photobleaching of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008, 53, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R.; Stedmon, C.A.; Graeber, D.; Bro, R. Fluorescence spectroscopy and multi-way techniques. PARAFAC. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 6557–6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, M.; Wünsch, U.; Weigelhofer, G.; Murphy, K.; Hein, T.; Graeber, D. staRdom: Versatile Software for Analyzing Spectroscopic Data of Dissolved Organic Matter in R. Water 2019, 11, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadoux, A.M.-C.; Malone, B.; Minasny, B.; Fajardo, M.; McBratney, A.B. Soil Spectral Inference with r; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aksenov, A.A.; Laponogov, I.; Zhang, Z.; Doran, S.L.F.; Belluomo, I.; Veselkov, D.; Bittremieux, W.; Nothias, L.F.; Nothias-Esposito, M.; Maloney, K.N.; et al. Auto-deconvolution and molecular networking of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa, J.M.; Gonzalez-Perez, J.A.; Gonzalez-Vazquez, R.; Knicker, H.; Lopez-Capel, E.; Manning, D.A.C.; Gonzalez-Vila, F.J. Use of pyrolysis/GC-MS combined with thermal analysis to monitor C and N changes in soil organic matter from a Mediterranean fire affected forest. Catena 2008, 74, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. Package ‘ggplot2’. In Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- van den Boogaart, K.G.; Tolosana-Delgado, R. “compositions”: A unified R package to analyze compositional data. Comput. Geosci. 2008, 34, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Package ‘vegan’. In Community Ecology Package, Version. 2013, Volume 2, pp. 1–295. Available online: https://mirror.ibcp.fr/pub/CRAN/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra. R Package. Version 1.0.6. Available online: https://github.com/kassambara/factoextra (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician 2017, 56, e24. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Arbizu, P. pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison Using Adonis. R Package. Version 0.4. Available online: https://github.com/pmartinezarbizu/pairwiseAdonis (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kholodov, V.A.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Yashin, M.A.; Frid, A.S.; Lazarev, V.I.; Tyugai, Z.N.; Milanovskiy, E.Y. Contact angles of wetting and water stability of soil structure. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2015, 48, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid, A.S.; Kuznetsova, I.V.; Koroleva, I.E.; Bondarev, A.G.; Kogut, B.M.; Utkaeva, V.F.; Kuznetsova, I.V.; Azovceva, N.A. Zonal-Provincial Measurement Standards of Agrochemical, Physical-Chemical, and Physical Indices of General Arable Soils in European Part of Russia under Anthropogenic Load: Methodological Guide; Dokuchaev Soil Science Inst.: Moscow, Russia, 2010; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Kholodov, V.A.; Farkhodov, Y.R.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Aydiev, A.Y.; Lazarev, V.I.; Ilyin, B.S.; Ivanov, A.L.; Kulikova, N.A. Thermolabile and Thermostable Organic Matter of Chernozems under Different Land Uses. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, A.A.; Zolotareva, B.N.; Kolyagin, Y.G.; Kudeyarov, V.N. Transformation of the organic matter in an agrogray soil and an agrochernozem in the course of the humification of corn biomass. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2013, 46, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. Photoacoustic and photothermal methods in spectroscopy and characterization of soils and soil organic matter. Photoacoustics 2020, 17, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. Organic Matter and Mineral Composition of Silicate Soils: FTIR Comparison Study by Photoacoustic, Diffuse Reflectance, and Attenuated Total Reflection Modalities. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margenot, A.J.; Parikh, S.J.; Calderón, F.J. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy for soil organic matter analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2023, 87, 1503–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuravuori, J.; Pihlaja, K. Molecular size distribution and spectroscopic properties of aquatic humic substances. Anal. Chim. Acta 1997, 337, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Mannaerts, C.M.; Lievens, C. Assessment of UV-VIS spectra analysis methods for quantifying the absorption properties of chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM). Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1152536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.M.; Boyer, E.W.; Westerhoff, P.K.; Doran, P.T.; Kulbe, T.; Andersen, D.T. Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2001, 46, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, A.; Vacher, L.; Relexans, S.; Saubusse, S.; Froidefond, J.M.; Parlanti, E. Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Org. Geochem. 2009, 40, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.A.; Amon, R.M.W.; Stedmon, C.A. Variations in high-latitude riverine fluorescent dissolved organic matter: A comparison of large Arctic rivers. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2013, 118, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R.; Hambly, A.; Singh, S.; Henderson, R.K.; Baker, A.; Stuetz, R.; Khan, S.J. Organic Matter Fluorescence in Municipal Water Recycling Schemes: Toward a Unified PARAFAC Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 2909–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totsche, K.U.; Amelung, W.; Gerzabek, M.H.; Guggenberger, G.; Klumpp, E.; Knief, C.; Lehndorff, E.; Mikutta, R.; Peth, S.; Prechtel, A.; et al. Microaggregates in soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2018, 181, 104–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronick, C.J.; Lal, R. Soil structure and management: A review. Geoderma 2005, 124, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woche, S.K.; Goebel, M.-O.; Kirkham, M.B.; Horton, R.; Van der Ploeg, R.R.; Bachmann, J. Contact angle of soils as affected by depth, texture, and land management. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2005, 56, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodov, V.A.; Milanovskiy, E.Y.; Konstantinov, A.I.; Tyugai, Z.N.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Perminova, I.V. Irreversible sorption of humic substances causes a decrease in wettability of clay surfaces as measured by a sessile drop contact angle method. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, T.A. Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Soils: Sources, Composition, Concentrations, and Functions: A Review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, C.; Liu, W.-S.; Liu, W.-X.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Bai, W.; Li, L.-J.; Lal, R.; Zhang, H.-L. Responses of soil pH to no-till and the factors affecting it: A global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murage, E.W.; Voroney, P.R.; Kay, B.D.; Deen, B.; Beyaert, R.P. Dynamics and Turnover of Soil Organic Matter as Affected by Tillage. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, M.; Gregorich, E.G.; Beare, M.H.; Ellert, B.H.; Simpson, M.J. Distinct dynamics of plant- and microbial-derived soil organic matter in relation to varying climate and soil properties in temperate agroecosystems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2023, 361, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T.; He, Z.; Tazisong, I.A.; Senwo, Z.N. Influence of Tillage, Cropping, and Nitrogen Source on the Chemical Characteristics of Humic Acid, Fulvic Acid, and Water-Soluble Soil Organic Matter Fractions of a Long-Term Cropping System Study. Soil Sci. 2009, 174, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.D. Microbial drought resistance may destabilize soil carbon. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D.A. Plant residue biochemistry regulates soil carbon cycling and carbon sequestration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Ma, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Wu, W.; Du, Z. Conservation tillage for 17 years alters the molecular composition of organic matter in soil profile. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 143116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: A mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudley, M.W.; Green, T.R.; Ascough, J.C. Tillage effects on soil hydraulic properties in space and time: State of the science. Soil Tillage Res. 2008, 99, 4–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Kelleher, B.P. FT-IR spectroscopic analysis of kaolinite–microbial interactions. Vib. Spectrosc. 2012, 61, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leue, M.; Eckhardt, K.-U.; Ellerbrock, R.H.; Gerke, H.H.; Leinweber, P. Analyzing organic matter composition at intact biopore and crack surfaces by combining DRIFT spectroscopy and Pyrolysis-Field Ionization Mass Spectrometry#. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2016, 179, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Vinay, N.; Wang, D.; Mo, F.; Liao, Y.; Wen, X. Microbial functional genes within soil aggregates drive organic carbon mineralization under contrasting tillage practices. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3618–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.B.; Canadell, J.; Ehleringer, J.R.; Mooney, H.A.; Sala, O.E.; Schulze, E.D. A global analysis of root distributions for terrestrial biomes. Oecologia 1996, 108, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, W.M.; Kwon, K.C. Soil carbon sequestration and land-use change: Processes and potential. Glob. Change Biol. 2000, 6, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Salgueiro, L.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Merino, A.; Vega, J.A.; Fonturbel, M.T.; Simal-Gandara, J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil Organic Horizons Depending on the Soil Burn Severity and Type of Ecosystem. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 2112–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-González, M.A.; Álvarez, A.M.; Carral, P.; González-Pérez, J.A.; Almendros, G. Climate variability in Mediterranean ecosystems is reflected by soil organic matter pyrolytic fingerprint. Geoderma 2020, 374, 114443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccanti, B.; Masciandaro, G.; Macci, C. Pyrolysis-gas chromatography to evaluate the organic matter quality of a mulched soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 97, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaal, J.; Rumpel, C. Can pyrolysis-GC/MS be used to estimate the degree of thermal alteration of black carbon? Org. Geochem. 2009, 40, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaal, J.; Martinez-Cortizas, A.; Nierop, K.G.J.; Buurman, P. A detailed pyrolysis-GC/MS analysis of a black carbon-rich acidic colluvial soil (Atlantic ranker) from NW Spain. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 2395–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendros, G.; Hernandez, Z.; Sanz, J.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, S.; Jiménez-González, M.; González-Pérez, J. Graphical statistical approach to soil organic matter resilience using analytical pyrolysis data. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1533, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buurman, P.; Peterse, F.; Almendros Martin, G. Soil organic matter chemistry in allophanic soils: A pyrolysis-GC/MS study of a Costa Rican Andosol catena. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 1330–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabanian, M. Molecular geochemistry of soil organic matter by pyrolysis gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) technique: A review. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 2013, 4, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenea, K.; Derenne, S.; Gonzalez-Vila, F.J.; Gonzalez-Perez, J.A.; Mariotti, A.; Largeau, C. Double-shot pyrolysis of the non-hydrolys able organic fraction isolated from a sandy forest soil (Landes de Gascogne, South-West France)—Comparison with classical Curie point pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl Pyrol 2006, 76, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girona-García, A.; Badía-Villas, D.; Jiménez-Morillo, N.T.; González-Pérez, J.A. Changes in soil organic matter composition after Scots pine afforestation in a native European beech forest revealed by analytical pyrolysis (Py-GC/MS). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.D.; Lowery, B.; Daniel, T.C. Soil Moisture Regimes of Three Conservation Tillage Systems. Trans. ASAE 1984, 27, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Ros, G.H.; Furtak, K.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Soil carbon sequestration—An interplay between soil microbial community and soil organic matter dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virto, I.; Barré, P.; Burlot, A.; Chenu, C. Carbon input differences as the main factor explaining the variability in soil organic C storage in no-tilled compared to inversion tilled agrosystems. Biogeochemistry 2012, 108, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, M.; Tosi, M.; Dunfield, K.E.; Hooker, D.C.; Simpson, M.J. Tillage management exerts stronger controls on soil microbial community structure and organic matter molecular composition than N fertilization. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 336, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-González, M.A.; Álvarez, A.M.; Hernández, Z.; Almendros, G. Soil carbon storage predicted from the diversity of pyrolytic alkanes. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Chorover, J. Transport and Fractionation of Dissolved Organic Matter in Soil Columns. Soil Sci. 2003, 168, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panettieri, M.; Knicker, H.; Murillo, J.M.; Madejón, E.; Hatcher, P.G. Soil organic matter degradation in an agricultural chronosequence under different tillage regimes evaluated by organic matter pools, enzymatic activities and CPMAS 13C NMR. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Vancov, T.; Jin, X.; Gao, Q.; Dong, W.; Du, Z. No-tillage farming for two decades increases plant- and microbial-biomolecules in the topsoil rather than soil profile in temperate agroecosystem. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 241, 106108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracchi, L.M.; Panahabadi, R.; Barros-Rios, J.; Bartley, L.E.; Sanguinet, K.A. Grass lignin: Biosynthesis, biological roles, and industrial applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1343097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wasswa, J.; Feldman, A.C.; Kabenge, I.; Kiggundu, N.; Zeng, T. Suspect screening to support source identification and risk assessment of organic micropollutants in the aquatic environment of a Sub-Saharan African urban center. Water Res. 2022, 220, 118706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golchin, A.; Oades, J.M.; Skjemstad, J.O.; Clarke, P. Study of free and occluded particulate organic-matter in soils by solid-state c-13 cp/mas nmr-spectroscopy and scanning electron-microscopy. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1994, 32, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchenko, N.N.; Artemyeva, Z.S.; Kolyagin, Y.G.; Kogut, B.M. A Comparative Study of the Humic Substances and Organic Matter in Physical Fractions of Haplic Chernozem under Contrasting Land Uses. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faix, O. Classification of Lignins from Different Botanical Origins by FT-IR Spectroscopy. Holzforschung 1991, 45, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspolli Galletti, A.M.; D’Alessio, A.; Licursi, D.; Antonetti, C.; Valentini, G.; Galia, A.; Nassi o Di Nasso, N. Midinfrared FT-IR as a Tool for Monitoring Herbaceous Biomass Composition and Its Conversion to Furfural. J. Spectrosc. 2015, 2015, 719042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodov, V.A.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Ziganshina, A.R.; Danchenko, N.N.; Danilin, I.V.; Farkhodov, Y.R.; Zhidkin, A.P. Water-Extractable Organic Matter of the Soils with Different Degrees of Erosion and Sedimentation in a Small Catchment in the Central Forest-Steppe of the Central Russian Upland: Soil Sediments on the Dry Valley Bottom. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2024, 57, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkhodov, Y.R.; Nikitin, D.A.; Yaroslavtseva, N.V.; Maksimovich, S.V.; Ziganshina, A.R.; Danilin, I.V.; Kholodov, V.A.; Semenov, M.V.; Zhidkin, A.P. Composition of Organic Matter and Biological Properties of Eroded and Aggraded Soils of a Small Catchment in the Forest-Steppe Zone of the Central Russian Upland. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2024, 57, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnos, M.; Calka, A.; Jozefaciuk, G. Wettability of mineral soils. Geoderma 2013, 206, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.; Gerke, H.H.; Ellerbrock, R.H.; Hallett, P.D.; Horn, R. Relating soil organic matter composition to soil water repellency for soil biopore surfaces different in history from two Bt horizons of a Haplic Luvisol. Ecohydrology 2018, 11, e1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Dueñas, F.J.; Martínez, Á.T. Microbial degradation of lignin: How a bulky recalcitrant polymer is efficiently recycled in nature and how we can take advantage of this. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.H.; Gerke, H.H.; Bachmann, J.; Goebel, M.-O. Composition of Organic Matter Fractions for Explaining Wettability of Three Forest Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 69, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainju, U.M. Carbon and Nitrogen Pools in Soil Aggregates Separated by Dry and Wet Sieving Methods. Soil Sci. 2006, 171, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beare, M.H.; Hendrix, P.F.; Coleman, D.C. Water-Stable Aggregates and Organic Matter Fractions in Conventional- and No-Tillage Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1994, 58, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Shao, J.; Fu, Y.; Liang, C.; Yan, E.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Bai, S.H. Differential magnitude of rhizosphere effects on soil aggregation at three stages of subtropical secondary forest successions. Plant Soil 2019, 436, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R.; Preston, C.M.; Nierop, K.G.J. Strengthening the soil organic carbon pool by increasing contributions from recalcitrant aliphatic bio(macro)molecules. Geoderma 2007, 142, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, D.; Lehmann, J. Modelling the long-term response to positive and negative priming of soil organic carbon by black carbon. Biogeochemistry 2012, 111, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Guéguen, C. Size distribution of absorbing and fluorescing DOM in Beaufort Sea, Canada Basin. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2017, 121, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsolnay, A.; Baigar, E.; Jimenez, M.; Steinweg, B.; Saccomandi, F. Differentiating with fluorescence spectroscopy the sources of dissolved organic matter in soils subjected to drying. Chemosphere 1999, 38, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.-P.; Huang, W.-S.; Chen, T.-C.; Yeh, Y.-L. Fluorescence Characteristics of Dissolved Organic Matter (DOM) in Percolation Water and Lateral Seepage Affected by Soil Solution (S-S) in a Lysimeter Test. Sensors 2019, 19, 4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Du, Y.; Das, P.; Lamore, A.F.; Dimova, N.T.; Elliott, M.; Broadbent, E.N.; Roebuck, J.A.; Jaffé, R.; Lu, Y. Agricultural land use changes stream dissolved organic matter via altering soil inputs to streams. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, T.; Zacháry, D.; Jakab, G.; Szalai, Z. Chemical composition of labile carbon fractions in Hungarian forest soils: Insight into biogeochemical coupling between DOM and POM. Geoderma 2022, 419, 115867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coble, P.G. Characterization of marine and terrestrial DOM in seawater using excitation-emission matrix spectroscopy. Mar. Chem. 1996, 51, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, V.; Romera-Castillo, C.; Forja, J. Dissolved Organic Matter in the Gulf of Cádiz: Distribution and Drivers of Chromophoric and Fluorescent Properties. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, T.; Bouillon, S.; Darchambeau, F.; Massicotte, P.; Borges, A.V. Shift in the chemical composition of dissolved organic matter in the Congo River network. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 5405–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuile Bistarelli, L.; Poyntner, C.; Santín, C.; Doerr, S.H.; Talluto, L.; Singer, G.; Sigmund, G. Wildfire-Derived Pyrogenic Carbon Modulates Riverine Organic Matter and Biofilm Enzyme Activities in an In Situ Flume Experiment. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, Y.; Panton, A.; Mahaffey, C.; Jaffé, R. Assessing the spatial and temporal variability of dissolved organic matter in Liverpool Bay using excitation–emission matrix fluorescence and parallel factor analysis. Ocean. Dyn. 2011, 61, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, M.; Dittmar, T.; Zielinski, O.; Kida, M.; Asp, N.E.; de Rezende, C.E.; Schnetger, B.; Seidel, M. Outwelling of reduced porewater drives the biogeochemistry of dissolved organic matter and trace metals in a major mangrove-fringed estuary in Amazonia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2024, 69, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Gao, H.; Yu, H.; Liu, D.; Zhu, N.; Wan, K. Insight into variations of DOM fractions in different latitudinal rural black-odor waterbodies of eastern China using fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with structure equation model. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vines, M.; Terry, L.G. Evaluation of the biodegradability of fluorescent dissolved organic matter via biological filtration. AWWA Water Sci. 2020, 2, e1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coble, P.G. Marine Optical Biogeochemistry: The Chemistry of Ocean Color. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coble, P.G.; Del Castillo, C.E.; Avril, B. Distribution and optical properties of CDOM in the Arabian Sea during the 1995 Southwest Monsoon. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 1998, 45, 2195–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Practice * | Soil Depth, cm | Contact Angle, ° | Kstr | MWDDSA | MWDWSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT | 0–10 | 17 ± 3 b ** | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.4 AB |

| 10–20 | 26 ± 6 a | ||||

| LT | 0–10 | 20 ± 5 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 B |

| 10–20 | 19 ± 3 | ||||

| MP | 0–10 | 19 ± 3 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 B |

| 10–20 | 17 ± 2 | ||||

| NT | 0–10 | 20 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.6 A |

| 10–20 | 21 ± 3 | ||||

| Till | 0–10 | 19 ± 2 | 0.9 ± 0.5 B *** | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 B |

| 10–20 | 20 ± 2 | ||||

| NT | 0–10 | 20 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.3 A | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.6 A |

| 10–20 | 21 ± 3 |

| Soil Depth, cm | Practice ** | pHH2O | pHKCl | P2O5, mg/kg | K2O, mg/kg | Corg, % | N, % | WEOC, mg/kg | WEN, mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0—10 | FT | 8.06 ± 0.09 AB * | 7.05 ± 0.03 | 60 ± 24 | 484 ± 36 | 2.31 ± 0.04 a | 0.25 ± 0.04 Aa | 44 ± 2 Aa | 9 ± 7 |

| LT | 8.09 ± 0.05 A | 7.11 ± 0.04 | 40 ± 13 | 454 ± 45 | 2.23 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.03 Ba | 44 ± 5 A | 8 ± 8 | |

| MP | 8.02 ± 0.17 AB | 7.09 ± 0.09 | 34 ± 22 | 448 ± 38 | 2.15 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.01 AB | 45 ± 8 A | 19 ± 8 | |

| NT | 7.86 ± 0.08 Bb | 7.01 ± 0.06 | 49 ± 29 | 500 ± 83 | 2.23 ± 0.15 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 ABa | 33 ± 2 Bb | 10 ± 8 | |

| 10—20 | FT | 8.05 ± 0.06 | 7.02 ± 0.06 | 51 ± 21 | 439 ± 34 | 1.78 ± 0.25 Bb | 0.38 ± 0.06 Ab | 39 ± 2b | 8 ± 5 |

| LT | 8.06 ± 0.04 | 7.10 ± 0.03 | 34 ± 6 | 437 ± 34 | 2.11 ± 0.15 AB | 0.29 ± 0.03 ABb | 42 ± 3 | 6 ± 4 | |

| MP | 8.02 ± 0.20 | 7.05 ± 0.15 | 48 ± 27 | 493 ± 110 | 2.17 ± 0.10 A | 0.24 ± 0.02 BC | 42 ± 6 | 10 ± 7 | |

| NT | 7.99 ± 0.04 a | 7.06 ± 0.04 | 32 ± 13 | 503 ± 89 | 1.73 ± 0.10 Bb | 0.18 ± 0.01 CDb | 41 ± 4 a | 7 ± 4 | |

| Comparison of pooled tilled soils with no tillage | |||||||||

| 0—10 | Till | 8.06 ± 0.09 A | 7.08 ± 0.02 A | 45 ± 16 | 462 ± 31 | 2.23 ± 0.09 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 44 ± 5 A | 9 ± 7 |

| NT | 7.86 ± 0.08 Bb | 7.01 ± 0.06 B | 49 ± 29 | 500 ± 83 | 2.23 ± 0.15 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 a | 33 ± 2 Bb | 10 ± 8 | |

| 10—20 | Till | 8.05 ± 0.08 | 7.05 ± 0.06 | 44 ± 11 | 457 ± 43 | 2.02 ± 0.11 Ab | 0.30 ± 0.07 Ab | 41 ± 3 | 8 ± 5 |

| NT | 7.99 ± 0.04 a | 7.06 ± 0.04 | 32 ± 13 | 503 ± 89 | 1.73 ± 0.15 Bb | 0.18 ± 0.01 Bb | 41 ± 4 a | 7 ± 4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farkhodov, Y.; Danchenko, N.; Danilin, I.; Grigoreva, I.; Matveeva, N.; Ziganshina, A.; Ermolaev, N.; Yudin, S.; Nadutkin, I.; Kambulov, S.; et al. Fingerprinting of Bulk and Water-Extractable Soil Organic Matter of Chernozems Under Different Tillage Practices for Twelve Years: A Case Study. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040138

Farkhodov Y, Danchenko N, Danilin I, Grigoreva I, Matveeva N, Ziganshina A, Ermolaev N, Yudin S, Nadutkin I, Kambulov S, et al. Fingerprinting of Bulk and Water-Extractable Soil Organic Matter of Chernozems Under Different Tillage Practices for Twelve Years: A Case Study. Soil Systems. 2025; 9(4):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040138

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarkhodov, Yulian, Natalia Danchenko, Igor Danilin, Irina Grigoreva, Natalia Matveeva, Aliia Ziganshina, Nikita Ermolaev, Sergey Yudin, Ivan Nadutkin, Sergey Kambulov, and et al. 2025. "Fingerprinting of Bulk and Water-Extractable Soil Organic Matter of Chernozems Under Different Tillage Practices for Twelve Years: A Case Study" Soil Systems 9, no. 4: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040138

APA StyleFarkhodov, Y., Danchenko, N., Danilin, I., Grigoreva, I., Matveeva, N., Ziganshina, A., Ermolaev, N., Yudin, S., Nadutkin, I., Kambulov, S., & Kholodov, V. (2025). Fingerprinting of Bulk and Water-Extractable Soil Organic Matter of Chernozems Under Different Tillage Practices for Twelve Years: A Case Study. Soil Systems, 9(4), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems9040138