Phytoavailability and Leachability of Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Agricultural Soils Ameliorated with Coal Fly Ash (CFA) and CFA-Treated Biosolids

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimentation

2.2. Amendments, Soils, Irrigation Water, Analyses

2.3. Mini-Lysimeter Study

2.4. The 220 L Lysimeter Study

2.5. Field Studies

2.6. Analyses and Quality Control

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Heavy Metal(loid)s in Lettuce Grown in CFA-Containing Mini-Lysimeters

3.1.1. Biomass

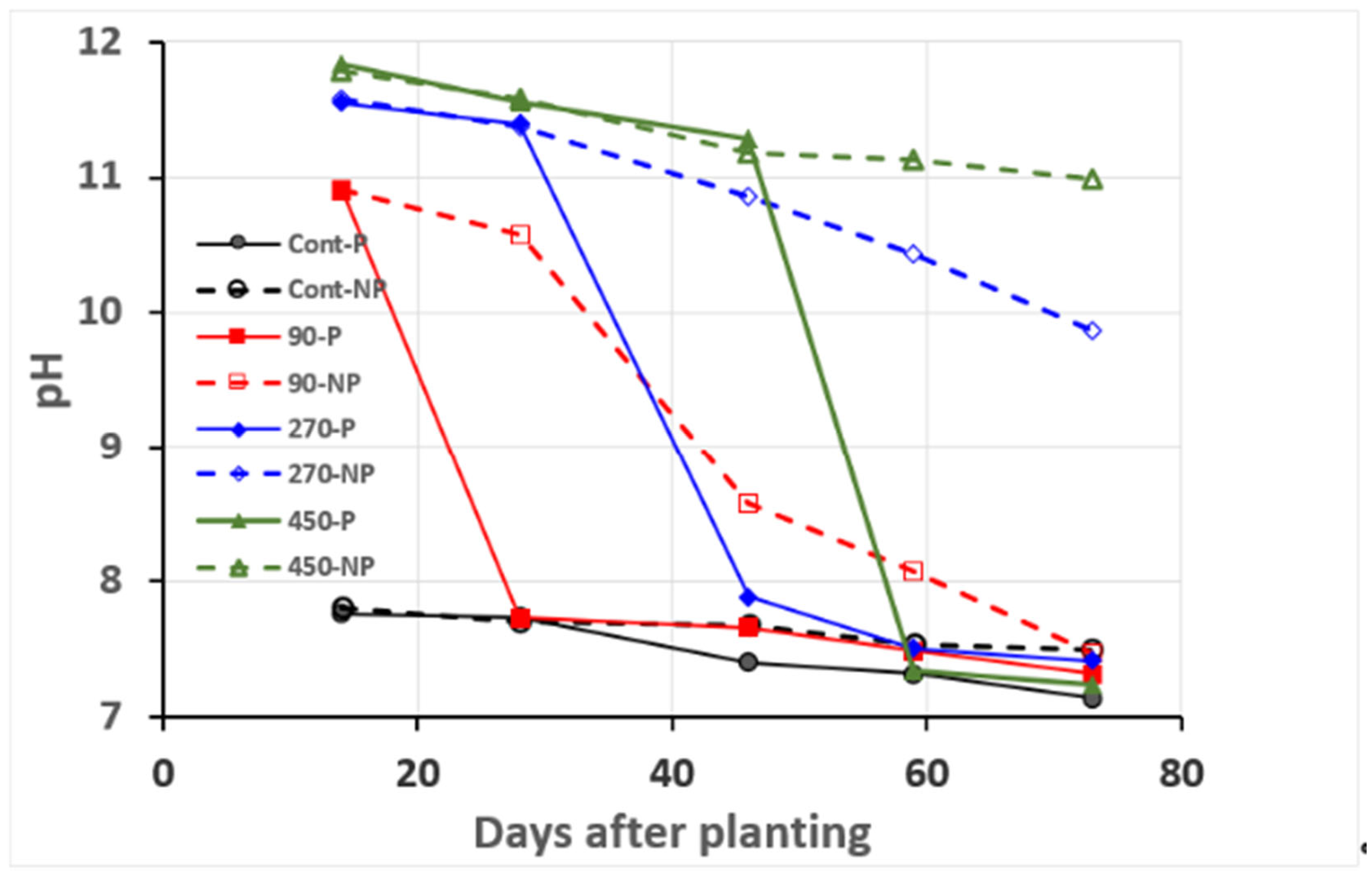

3.1.2. Leachate pH

3.1.3. Heavy Metals and Metalloids in the Lettuce Foliage and Leachate

3.2. Heavy Metal(loid)s in Lettuce Grown in 220-L Lysimeters

3.2.1. Effect of the Amendments on the Content of Elements in Soil, Plants, and Leachate

3.2.2. As, Cd, and Pb Contents in the Foliage of the Four Lettuce Crops

3.3. Heavy Metal(loid)s in Field Crops

| (a) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop | Potatoes (var. Vivaldi, Winston) | Potatoes (1) (var. Winston) | Carrots (var. Nairobi) | Lettuce (var. Iceberg) | Bell pepper (var. Gilad) | Peanuts (var. Hanoch; Seeds) | Chickpeas (var. Kabuli; Seeds) |

| Location and soil classification | Bsor, Nir-Oz, Yevul (Torripsamments) Nir-Eliyahu (Haploxeralfs) | Bsor R&D Center (Torripsa-mments) | Nir-Eliyahu (Haploxeralfs) | Ein-Habsor, Sde- Nitsan, Bet-Ezra, Kfer-Hayim (Torripsamments, Haploxerepts and Haploxeralfs) | Tomer (Haplargids) | Nir-Oz, Nirim (Torripsamments) | Revadim (a Sodic Haploxerert) |

| NVS load (dry mT ha−1) | 50–120 | 45 | 120 | 50–120 | 100 | 50 | CFA 800 |

| Yield (fresh mT ha−1) | 37–58 | (2) 55 vs. 65 | 9.1 | 30–50 | 92 | 6.5–8.1 (pods) | 4.2 (pods) |

| As (µg kg−1) | 9 (bdl-45) | Bdl | 40 (20–60) | 10 (bdl-80) | bdl | 210 (bdl-780) | 70 (bdl-0.16) |

| Cd (µg kg−1) | 35 (25–60) | 20 | 50 (30–130) | 160 (60–560) | 60 (bdl-100) | 40 (bdl-100) | 2 (bdl-20) |

| Pb (µg kg−1) | 130 (80–370) | 140 | Bdl | bdl-1.3 | bdl | 60 (bdl-700) | bdl |

| B (mg kg−1) | 27 (7–57) | 36 | 70 (45–100) | 60 (37–102) | 40 (10–90) | 16 (12–21) | 14 (11–17) |

| Cr (mg kg−1) | 0.17 (0.06–0.37) | 0.12 | 1.7 (0.7–4.5) | 0.44 (0.19–1.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.8) | 0.08 (bdl-0.31) | 0.56 (0.25–0.27) |

| Cu (mg kg−1) | 5 (4.3–6.0) | (2) 3.8 vs 4.5 | 5.4 (3–10) | 14 (4–104) | 10 (7–14) | 8 (5–10) | (2) 6 (5–8) |

| Fe (mg kg−1) | 16 (7–25) | 25 | 160 (70–330) | 97 (55–140) | 45 (26–134) | 17 (13–41) | 48 (42–58) |

| Mn (mg kg−1) | 6.5 (5.3–7.0) | 7.4 | 9 (6–20) | (3) 21 (14–63) | 13 (11–14) | 15 (11–20) | 26 (22–30) |

| Mo (mg kg−1) | 0.3 (0.16–0.50) | (2) 0.11 vs. 0.90 | (2) 0.7 (0.15–1.7) | (2) 0.3 (0.12–0.42) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 5.6 (2.2–10.1) | (2) 9 (4.4–14) |

| Ni (mg kg−1) | 0.29 (0.17–1.0) | 0.31 | 1.2 (0.49–2.8) | 1.0 (0.32–5.2) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.52 (0.25–1.12) | 1.0 (0.8–1.5) |

| P (g kg−1) | 0.238 (0.15–0.4) | (2) 0.14 vs 0.18 | 0.44 (0.31–0.64) | 0.83 (0.60–1.14) | 0.29 (0.21–0.40) | 0.42 (0.30–0.48) | 0.41 (0.39–0.43) |

| Se (mg kg−1) | - | (2) 0.009 vs 0.56 | - | - | 0.74 (bdl-1.4) | - | (2) 0.04 (bdl-1.4) |

| V (mg kg−1) | 0.01 (bdl-0.03) | 0.10 | 0.53 (0.2–1.1) | 0.14 (0.8–0.28) | 0.08 (bdl-0.3) | 0.03 (bdl-0.13) | 0.009 (bdl-0.03) |

| Zn (mg kg−1) | 25 (13–52) | 19 | 19 (12–30) | 54 (35–80) | 20 (13–24) | 43 (27–50) | (3) 19 (16–23) |

| (b) | |||||||

| Crop | Corn Canopy (+Cobs and Husks) | Corn Kernels | Wheat Canopy | Wheat Grains | Silage Wheat (at Wax Ripening) | Vetch and Clover | Corn (4) |

| Location and soil classification | Revadim (a Chromic Haploxerert) | Bnei-Darom (dune sand) | Mishmar David (a Lithic Xerorthent) | Revadim (a Sodic Haploxerert) | |||

| Load (dry mT ha−1) | 284 and 426 mT NVS ha−1, the 4-y cumulative loads at the low and high rates; double cropping: corn in summers, wheat in winters. | CFA: 300 and NVS: 100 | NVS: 95 | CFA: 800 | |||

| Yield (mT ha−1) | 34.1 (moist) | 6.8 (dry) | 29.3 mT (moist) | 3.1 (dry) | 10.6 (moist) | (2) 5.0 vs. 14 (dry) | 44 (total, moist) |

| As (µg kg−1) | 970 (130–7000) | bdl | 43 (bdl-160) | bdl | 60 (bdl-170) | 90 (10–250) | bdl |

| Cd (µg kg−1) | 22 (bdl-240) | 30 (bdl-620) | 30 (bdl-70) | 7 (0–130) | 32 (15–43) | 50 (30–100) | 8; 2 |

| Pb (µg kg−1) | 160 (bdl-430) | bdl | 160 (bdl-700) | 60 (0–750) | (2) 1400 (700–2800) | 200 (30–360) | 120; 40 |

| B (mg kg−1) | (2) 55 (27–127) | 23 (5–54) | 17 (3–37) | 13 (3–27) | 39 (17–63) | 46 (10–82) | 24; 7 |

| Cr (mg kg−1) | 1.5 (bdl-6.0) | 0.17 (0.06–0.40) | 0.5 (0.3–1.3) | 0.41 (0.11–9.0) | 0.60 (0.33–1.2) | 0.9 (0.5–2.7) | 6; (2) 3 |

| Cu (mg kg−1) | (2) 5.5 (2.4–9.6) | 1.4 (0.7–2.3) | 2.7 (1.4–4.0) | 5 (4–11) | 3.4 (2.6–4.7) | 8 (6–10) | 7.3; 2.6 |

| Fe (mg kg−1) | 135 (56–415) | 12 (7–22) | 134 (76–270) | 31 (19–63) | 188 (72–485) | 220 (117–440) | 150; 40 |

| Mn (mg kg−1) | (2) 51 (36–82) | 4 (3–5) | 68 (48–103) | 69 (58–82) | 29 (17–62) | 35 (16–54) | 29; 8 |

| Mo (mg kg−1) | (2) 0.07 (bdl-0.50) | 0.15 (0.05–0.35) | (2) 2.7 (1.5–4.0) | (2) 0.62 (0.3–2.8) | (2) 1.6 (0.4–2.3) | (2) 2.2 (0.4–5) | (2) 0.9; 0.6 |

| Ni (mg kg−1) | 0.20 (bdl-2.3) | 0.28 (0.13–0.64) | 0.21 (0.12–0.47) | 0.52 (0.3–2.5) | 0.34 (0.15–0.68) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 2.4; 1.4 |

| P (g kg−1) | 0.14 (0.04–0.35) | 0.28 (0.23–0.32) | 0.15 (0.08–0.21) | 0.38 (0.34–0.43) | 0.24 (0.21–0.27) | 0.29 (0.23–0.39) | 0.26; 0.40 |

| Se (mg kg−1) | - | - | - | - | (2) 0.53 (bdl-0.72) | - | - |

| V (mg kg−1) | 0.39 (0.19–0.76) | 0.01 (bdl-0.03) | 0.35 (0.19–0.72) | 0.06 (0.01–0.21) | 0.49 (0.18–1.3) | 0.56 (0.25–1.3) | 0.22; 0.012 |

| Zn (mg kg−1) | 28 (13–61) | 21 (17–27) | 11 (4.5–22) | 33 (24–57) | 23 (14–29) | (3) 41 (39–56) | 11; 19 |

3.4. Heavy Metal(loid)s Content and Potential Phytoavailability in the Treated Soils

3.4.1. Heavy Metal(loid)s Content

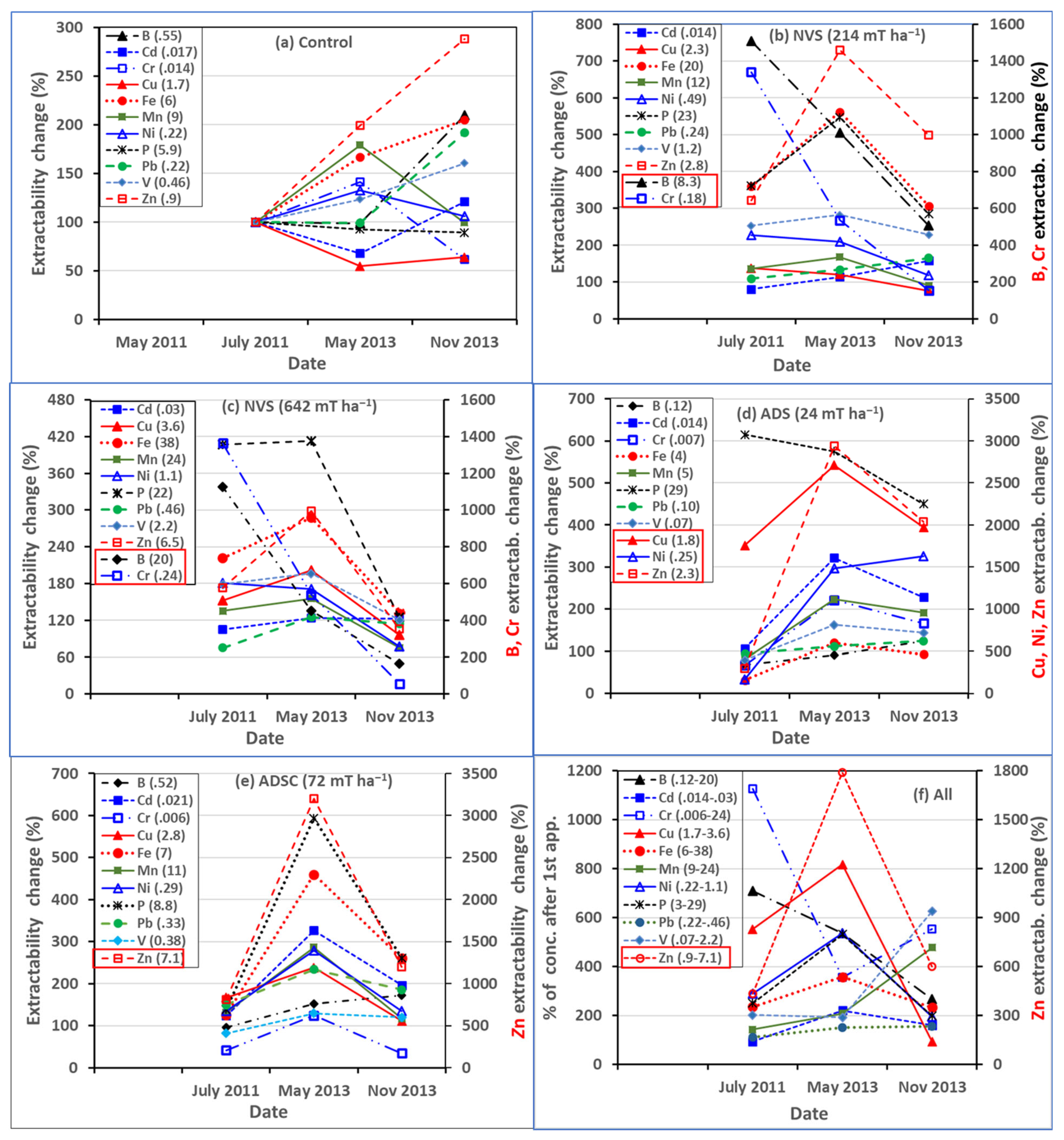

3.4.2. Potential Phytoavailability’ of Heavy Metal(loid)s

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Enerdata—Global Energy Trends. 2024. Available online: https://www.enerdata.net/publications/reports-presentations/world-energy-trends.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liao, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, T. A comprehensive review of toxicity of coal fly ash and its leachate in the ecosystem. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.; Heidrich, C.; Feuerborn, J. Global Aspects on Coal Combustion Products. 2019. Available online: https://www.asiancoalash.org/_files/ugd/ed8864_53ad887cdb1c4bbda4979c8069941a95.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Perilli, D. 2023 Update on Fly Ash in the US. Cement Industry News from Global Cement. 2023. Available online: https://www.globalcement.com/news/item/15657-update-on-fly-ash-in-the-us-april-2023 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Adams, T.H. 2022 Coal Ash Recycling Rate Increases Slightly in 2021; Use of Harvested Ash Grows Significantly. Available online: https://acaa-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/News-Release-Coal-Ash-Production-and-Use-2021.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Fine, P.; Mingelgrin, U. The effect of land application of sludge stabilized with coal fly ash and lime on soil and crop quality. In Ash at Work, Applications, Science, and Sustainability of Coal Ash; Adams, T., Ed.; American Coal Ash Association: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2018; pp. 10–13. Available online: https://acaa-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/ash-at-work/ASH01-2018.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Hadas, E.; Mingelgrin, U.; Fine, P. Economic cost–benefit analysis for the agricultural use of sewage sludge treated with lime and fly ash. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutsch, N. Environmental Assessment of Coal Fly Ash Usage in Agriculture and Infrastructure Projects in Israel. 2018. Available online: https://acaa-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/ash-at-work/ASH01-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Haynes, R.J. Reclamation and revegetation of fly ash disposal sites—Challenges and research needs. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambhulkar, H.P.; Shaikh, S.M.S.; Kumar, M.S. Fly ash toxicity, emerging issues and possible implications for its exploitation in agriculture; Indian scenario: A review. Chemosphere 2018, 213, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, I.A.M.; Loganathan, P.; Nissanka, S.P.; Manoharan, V.; Burchett, M.D.; Skilbeck, C.G.; Eamus, D. Application of Coal Fly Ash in Agriculture: A Strategic Perspective. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 42, 559–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.G.; Kazonich, G.; Dahlberg, M. Relative solubility of cations in class F fly ash. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 4507–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpiene, J.; Ore, S.; Lagerkvist, A.; Maurice, C. Stabilization of Pb- and Cu-contaminated soil using coal fly ash and peat. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 145, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Kunhikrishnan, A.; Thangarajan, R.; Kumpiene, J.; Park, J.; Makino, T.; Kirkham, M.B.; Scheckel, K. Remediation of heavy metal(loid)s contaminated soils—To mobilize or to immobilize? J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 266, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. USEPA Clean Water Act; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Part 503, Volume 58, No. 32, (40 CFR Part 503). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/biosolids/sewage-sludge-laws-and-regulations#standards (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Antoniadis, V.; Tsadilas, C.D.; Stamatiadis, S. Effect of Dissolved Organic Carbon on Zinc Solubility in Incubated Biosolids-Amended Soils. J. Environ. Qual. 2007, 36, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, A.; Mingelgrin, U.; Fine, P. Chapter 7: Heavy Metals in Soils Irrigated with Wastewater. In Treated Wastewater in Agriculture: Use and Impacts on the Soil Environment and Crops; Levy, G.J., Fine, P., Bar-Tal, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 247–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.B. Soluble Trace Metals in Alkaline Stabilized Sludge Products. J. Environ. Qual. 1998, 27, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, B.K.; Steenhuis, T.S.; Peverly, J.H.; McBride, M.B. Effect of sludge-processing mode, soil texture and soil pH on metal mobility in undisturbed soil columns under accelerated loading. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 109, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, T.J.; Goins, L.E.; Lindsay, B.J. Field assessment of trace element uptake by six vegetables from N-Viro Soil. Water Environ. Res. 1997, 69, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrabrants, A.C.; Kosson, D.S.; Stefanski, L.; DeLapp, R.; Seignette, P.F.A.B.; van der Sloot, H.A.; Kariher, P.; Baldwin, M. Interlaboratory Validation of the Leaching Environmental Assessment Framework (LEAF) Method 1313 and Method 1316; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; EPA 600/R-12/623.

- Kim, B.; McBride, M.B.; Richards, B.K.; Steenhuis, T.S. The long-term effect of sludge application on Cu, Zn, and Mo behavior in soils and accumulation in soybean seeds. Plant Soil 2007, 299, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, J.J.; Basta, N.T. Remediation of Acid Soils by Using Alkaline Biosolids. J. Environ. Qual. 1995, 24, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, W.L. Chemical Equilibria in Soils; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yephet, Y.; Tsror, L.; Reuven, M.; Gips, A.; Bar, Z.; Einstein, A.; Turjeman, Y.; Fine, P. Effect of alkaline-stabilized sludge (Ecosoil) and NH4 in controlling soilborne pathogens. Acta Hortic. 2006, 698, 115–122, ISHS 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gips, A. 2008 Suppression of Soil-Borne Pathogens by Ammonia. Ph.D. Thesis, Senate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel, 2008. (In Hebrew with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sajwan, K.S.; Paramasivam, S.; Alva, A.K.; Adriano, D.C.; Hooda, P.S. Assessing the feasibility of land application of fly ash, sewage sludge and their mixtures. Adv. Environ. Res. 2003, 8, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.J.; Burnham, J.C. The alkaline stabilization with accelerated drying process (N-Viro): An advanced technology to convert sewage sludge into a soil product. In Agriculture Utilization of Urban and Industrial By-Products; Karlen, D.L., Wright, R.J., Kemper, W.O., Eds.; ASA Special Publication No 58; ASA, CSSA, NVSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, T.J.; Lindsay, B.J.; Goins, L.E.; Ryan, J.A. Field Assessment of Sludge Metal Bioavailability to Crops: Sludge Rate Response. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermiyahu, U.; Tal, A.; Ben-Gal, A.; Bar-Tal, A.; Tarchitzky, J.; Lahav, O. Rethinking desalinated water quality and agriculture. Science 2007, 318, 920–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, O.; Kochva, M.; Tarchitzky, J. Potential drawbacks associated with agricultural irrigation with treated wastewaters from desalinated water origin and possible remedies. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, Y.; Pivonia, S. Use of ammonia- releasing compounds for control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Nematology 2002, 4, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, Y.; Tkachi, N.; Shuker, S.; Rosenberg, R.; Suriano, S.; Fine, P. Laboratory studies on the enhancement of nematicidal activity of ammonia-releasing fertlisers by alkaline amendments. Nematology 2006, 8, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, Y.; Shapira, N.; Fine, P. Control of root-knot nematodes in organic farming systems by organic amendments and soil solarization. Crop. Prot. 2007, 26, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I. Factors affecting the suppression of Heterodera glycines by N-Viro Soil. J. Nematol. 2005, 37, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zasada, I.A.; Avendano, F.; Li, Y.C.; Logan, T.J.; Melakeberhan, H.; Koenning, S.R.; Tylka, G.L. Potential of an alkaline-stabilized biosolid to manage nematodes: Case studies on soybean cyst and root-knot nematodes. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.A.; Tenuta, M. Alteration of the soil environment to maximize Meloidogyne incognita suppression by an alkaline-stabilized biosolid amendment. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 40, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, L.C.; Masto, R.E. Fly ash for soil amelioration: A review on the influence of ash blending with inorganic and organic amendments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 128, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpiene, J.; Lagerkvist, A.; Maurice, C. Stabilization of As, Cr, Cu, Pb and Zn in soil using amendments—A review. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, J. Soil chronosequences in Israel. Catena 1983, 10, 287–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyumdjisky, H.; Dan, J.; Suriano, S.; Nisim, S. Selected Soil Profile Descriptions of Soils of the Land of Israel; ARO, Volcani Center, Institute of Soil, Water and Environmental Sciences: Rishon LeZion, Israel, 1988; p. 250. (In Hebrew)

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 13th ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Fine, P.; Hass, A.; Prost, R.; Atzmon, N. Organic carbon leaching from effluent irrigated lysimeters as affected by residence time. Soil Sci. Soc. 2002, 66, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Test Method 3052: Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Siliceous and Organically Based Matrices, Part of Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste, Physical-Chemical Methods. 1996. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/3052.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Fine, P.; Rathod, P.H.; Beriozkin, A.; Hass, A. Chelant-enhanced heavy metal uptake by Eucalyptus trees under controlled deficit irrigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shargil, D.; Gerstl, Z.; Fine, P.; Nitsan, I.; Kurtzman, D. Impact of biosolids and wastewater effluent application to agricultural land on steroidal hormone content in lettuce plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, W.L.; Norvell, W.A. Development of a DTPA Soil Test for Zinc, Iron, Manganese, and Copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1978, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JMP®, Version 16; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 1989–2023.

- Eshel, G.; Singer, M.J. Chapter 5: Calcium and carbonate. In Treated Wastewater in Agriculture: Use and Impacts on the Soil Environment and Crops; Levy, G.J., Fine, P., Bar-Tal, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, A. Chemical Characteristics of Soilless Media. In Soilless Culture: Theory and Practice Theory and Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Klassen, W. Effects of Soil Amendments at a Heavy Loading Rate Associated with Cover Crops as Green Manures on the Leaching of Nutrients and Heavy Metals from a Calcareous Soil. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2003, 38, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352532/9789240045064-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Paranychianakis, N.Y.; Salgot, M.; Angelakis, A.N. Chapter 3, Irrigation with Recycled Water: Guidelines and Regulations. In Treated Wastewater in Agriculture: Use and Impacts on the Soil Environment and Crops; Levy, G.J., Fine, P., Bar-Tal, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgaki, M.N.; Mytiglaki, C.; Tsokkou, S.; Kantiranis, N. Leachability of hexavalent chromium from fly ash-marl mixtures in Sarigiol basin, Western Macedonia, Greece: Environmental hazard and potential human health risk. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermiyahu, U.; Ben-Gal, A.; Keren, R. Chapter 6.1: Boron. In Treated Wastewater in Agriculture: Use and Impacts on the Soil Environment and Crops; Levy, G.J., Fine, P., Bar-Tal, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaway, W.H. Agronomic control over the environmental cycling of trace elements. Adv. Agron. 1968, 20, 235–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, N.T.; Ryan, J.A.; Chaney, R.L. Trace Element Chemistry in Residual-Treated Soil: Key Concepts and Metal Bioavailability. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Edna, S.; Fernandes, A.R.; de Souza Braz, A.M.; Sabino Lorena, L.L.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in soils from the surroundings of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandy, S.; Ammann, A.; Schulin, R.; Nowack, B. Biodegradation and speciation of residual SS-ethylenediaminedisuccinic acid (EDDS) in soil solution left after soil washing. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 142, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.; Carmeli, S.; Borisover, M.; Hayat, R.; Beriozkin, A.; Hass, A.; Mingelgrin, U. Properties of the DOM in Soil Irrigated with Wastewater Effluent and Its Interaction with Copper Ions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.; Engal, O.; Beriozkin, A. EDTA biodegradability and assisted phytoextraction efficiency in a large-scale field simulation: Is EDTA phasing out justified? J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, K.R.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Reid, R.J. The uptake and partitioning of cadmium in two cultivars of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Roco, M.; Gómez, V.; Kalazich, J.; Hernández, J. Cadmium (Cd) Accumulation in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cropping Systems: A Review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 1574–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.; Rathod, P.H.; Beriozkin, A.; Mingelgrin, U. Uptake of Cadmium by Hydroponically Grown, Mature Eucalyptus camaldulensis Saplings and the Effect of Organic Ligands. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2013, 15, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehouwer, R.C.; Macneal, K.E. Effect of Alkaline-Stabilized Biosolids on Alfalfa Molybdenum and Copper Content. J. Environ. Qual. 2004, 33, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, B.N.; Gridley, K.L.; Brady, J.N.; Phillips, T.; Tyerman, S.D. The Role of Molybdenum in Agricultural Plant Production. Ann. Bot. 2005, 96, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Chapter 21: Molybdenum. In Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and their Bioavailability, 3rd ed.; Environmental Pollution; Alloway, B.J., Ed.; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 22, pp. 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramićanin, A.; Andrić, F.; Mutić, J.; Stanković, V.; Momirović, N.; Milojković-Opsenica, D. Content and distribution of major and trace elements as a tool to assess the genotypes, harvesting time, and cultivation systems of potato. Food Chem. 2021, 354, 129507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC—Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; TABLE 15-3; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Available online: https://profsite.um.ac.ir/~kalidari/software/NRC/HELP/NRC%202001.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Uchimiya, M.; Bannon, D.; Nakanishi, H.; McBride, M.B.; Williams, M.A.; Yoshihara, T. Chemical Speciation, Plant Uptake, and Toxicity of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12856–12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmann, H.; Mattsson, L.; Eriksson, J. Trace element concentration in wheat grain: Results from the Swedish long-term soil fertility experiments and national monitoring program. Environ. Geochem. Health 2009, 31, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.; Scagnossi, A.; Chen, Y.; Mingelgrin, U. Removal of Transition Metals from Aqueous Systems by Peat: The Cadmium Case. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 138, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, A. Chemical Distribution of Heavy Metals in Biosolids Treated Soils. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Agricultural, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel, 2002. (In Hebrew with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, I.W.; Hass, A.; Merrington, G.; Fine, P.; McLaughlin, M.J. Copper availability in 7 Israeli soils incubated with and without biosolids. J. Environ. Qual. 2004, 34, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, Y.; Fine, P.; Levkovitch, I.; Baram, S. Effects of the origins and stabilization of biosolids and biowastes on their phosphorous composition and extractability. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.B. Toxic Metal Accumulation from Agricultural Use of Sludge: Are USEPA Regulations Protective? J. Environ. Qual. 1995, 24, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasto, S.; Baldassano, D.; Sabatino, L.; Caldarella, R.; Di Rosa, L.; Baldassano, S. The Role of Consumption of Molybdenum Biofortified Crops in Bone Homeostasis and Healthy Aging. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Units (Dry Weight) | CFA (Fresh) | NVS | ADS | ADSC | WWE (1) (mg L−1 and kg ha−1y−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific density | kg L−1 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.57 | ||

| Dry weight | kg kg−1 | 1.0 | 0.71 | 0.20 | 0.59 | |

| Specific density dry | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.34 | |||

| Ash | g kg−1 | ~950 | 880 | 240 | 530 | |

| TOC | -”- | 2.31 | 91.8 | 387 | 222 | 14 (56) |

| IC | -”- | 0.29 | 15.5 | 0.67 | 2.8 | |

| DOC | mg kg−1 | 1420 | 23,150 | 70,560 | 15,400 | |

| DOC/TOC | Ratio | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.07 | |

| Total N | g kg−1 | 0.064 | 7.0 | 63 | 21 | 6.8 (27) |

| Total P | -”- | 0.128 | 3.6 | 23 | 13 | 2.4 (9.6) |

| K | -”- | 0.380 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 5.9 | 32 (120) |

| pH(1:5, solid–water) | −log[H+] | 12.0 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 8.4 |

| EC(1:5, solid–water) | dS m−1 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 7.8 | 6.6 | 1.80 |

| Cl | mg kg−1 | 217 | 40 | 360 | 650 | 340 (1360) |

| As | -”- | 32 | 13 | 1.9 | 2.1 | |

| B | -”- | 270 | 330 | 30 | 50 | 0.35 (1.4) |

| Ca | -”- | 31,235 | 56,000 | 39,400 | 70,500 | 70 (28) |

| Cd | -”- | 1.5 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 1.1 | bdl |

| Co | -”- | 21 | 0.5 | 76 | 6.4 | bdl |

| Cr | -”- | 134 | 77 | 153 | 111 | bdl |

| Cu | -”- | 44 | 40 | 540 | 230 | 0.01 (0.04) |

| Fe | -”- | 26,600 | 15,250 | 6150 | 5500 | 0.20 (0.8) |

| Hg | -”- | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | bdl |

| Mg | -”- | 6280 | 6400 | 7100 | 10,600 | 30 (120) |

| Mn | -”- | 225 | 200 | 240 | 200 | 0.04 (0.16) |

| Mo | -”- | 12 | 4.2 | 9.6 | 3.1 | 0.03 (0.13) |

| Na | -”- | 5550 | 825 | 1700 | 1900 | 280 (1120) |

| Ni | -”- | 49 | 42 | 108 | 63 | bdl |

| Pb | -”- | 44 | 30 | 32 | 39 | bdl |

| S | -”- | 2915 | 2650 | 11,700 | 7700 | 35 (140) |

| V | -”- | 135 | 65 | 21 | 23 | bdl |

| Zn | -”- | 72 | 150 | 3400 | 1200 | 0.06 (0.24) |

| Soil Classification (USDA-ARS) | Location Name | Location (Coordinates) | Texture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz sand | Sand dunes at Yavne and Bnei-Darom | 31°53′08.66″ N 34°43′19.26″ E and 31°49′38.30″ N 34°41′50.12″ E | Sand |

| Xeric Torripsamments | Bsor R&D Center, Sde-Nitsan, Nir Oz, Nirim, Ein HaBsor, Gevulot, Yevul (locations in the NW Negev) | 31°15′41.51″ N 34°23′29.01″ E | Sand and sandy loams |

| Calcic Haploxeralf | Nahal Oz | 31°28′30.82″ N 34°29′32.87″ E | Sandy clay loam |

| Chromic Haploxerert and Sodic Haploxerert | Revadim | 31°47′01.99″ N 34°49′34.40″ E | Fine clay |

| Lithic Xerorthent | Mishmar David (two locations) | 32°01′07.44″ N 35°27′09.60″ E | Loamy pale Rendzina with ca. 70% w/w CaCO3 |

| Typic Haplargid | Tomer (the lower Jordan valley) | 32°01′28.80″ N 35°27′41.65″ E | Calcareous clay (35% clay) |

| Typic Haploxerepts and Typic Haploxeralfs | Beit Ezra, Nir Elyyahu; Kfar Haim (locations in the Coastal Plains) | Between 31°44′02.59″ N 34°39′24.51″ E and 32°21′09.19″ N 34°53′49.96″ E | Sand to sandy clay loam |

| Treatment | As | Cd | Pb | Cr | Cu | Ni | Zn | B | Mn | Mo | Se | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a)Concentration in the CFA (mg kg−1) | ||||||||||||

| CFA | 10 | 0.7 | 70 | 165 | 75 | 95 | 85 | 200 | 400 | 8.5 | 3 | 160 |

| (b)Concentration in lettuce leaves at harvest (mg kg−1) (1) | ||||||||||||

| Sand | bdl b | 0.17 | 0.96 | 6.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 91 | 25 c | 75 a | 0.16 d | 0.12 | 1.1 b |

| 90 T ha−1 | 0.34 a | 0.21 | 1.05 | 18.2 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 64 | 53 bc | 89 a | 0.73 c | 0.1 | 1.8 ab |

| 270 T ha−1 | 0.52 a | 0.31 | 1.18 | 11.7 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 69 | 80 b | 60 b | 1.23 b | 0.21 | 1.9 ab |

| 450 T ha−1 | 0.64 a | 0.22 | 1.11 | 13.2 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 55 | 143 a | 48 b | 2.16 a | 0.14 | 2.1 a |

| Prob > F (1) | <0.001 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | Ns | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ns | <0.05 |

| Market plants | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 4.2 | 9.6 | 0.71 | 48 | 45 | 68 | 0.37 | bdl | 0.19 |

| Max allowed (2) | 5 | 1 | 1.5 | |||||||||

| (c)Average (±std) concentration of all 10 periodical leachates-planted and not-planted mini-lysimeters (3) | ||||||||||||

| µg L−1 | mg L−1 | µg L−1 | ||||||||||

| Sand–Planted | 14 ± 2 | bdl | bdl | bql | 7 ± 3 | 9 ± 8 | 79 ± 25 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 3 | 3 ± 1 | 15 ± 6 | 4 ± 1 |

| Sand–Not Pl. | 10 ± 0.4 | bdl | bdl | bql | 2 ± 0.2 | 4 ± 0.0 | 30 ± 5 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.3 | 10 ± 2.4 | 6 ± 0.2 |

| 90 T ha−1–P | 29 ± 4 | bdl | bdl | 410 ± 90 | 28 ± 6 | 19 ± 4 | 65 ± 25 | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 2 ± 2 | 193 ± 40 | 16 ± 3 | 196 ± 17 |

| 90 T ha−1–NP | 14 ± 2 | bdl | bdl | 45 ± 14 | 3 ± 1 | 4 ± 0 | 8 ± 1 | 1.26 ± 0.14 | 2 ± 1 | 19 ± 3 | 8 ± 3 | 129 ± 21 |

| 270 T ha−1–P | 19 ± 4 | bdl | bdl | 470 ± 240 | 12 ± 3 | 13 ± 6 | 60 ± 23 | 7.3 ± 2.0 | 14 ± 10 | 351 ± 109 | 16 ± 5 | 62 ± 5 |

| 270 T ha−1–NP | 10 ± 2 | bdl | bdl | 370 ± 60 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 30 ± 14 | 0.75 ± 0.09 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 158 ± 36 | 8 ± 3 | 44 ± 2 |

| 450 T ha−1–P | 28 ± 4 | bdl | bdl | 4000 ± 540 | 9 ± 1 | 115 ± 13 | 51 ± 21 | 10.7 ± 1.6 | 15 ± 19 | 1065 ± 34 | 26 ± 5 | 45 ± 12 |

| 450 T ha−1–NP | 9 ± 1 | bdl | bdl | 86 ± 7 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.0 | 21 ± 8 | 2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 99 ± 22 | 9 ± 2 | 23 ± 1 |

| DL/QL | ||||||||||||

| WHO [52] | 10 | 3 | 10 | 50 | 2000 | 70 | - | 2.4 | - | - | 40 | - |

| Treatment (1) | As | Cd | Pb | Cr | Cu | Ni | Zn | B | Mn | Mo | V | P | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Calculated amount of elements loaded at the 15 cm lysimeters’ soil layer over the 3 y period (mg kg−1) (2) | |||||||||||||

| NVS-214 mT ha−1 | 1.5 | 0.06 | 3.4 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 16 | 37 | 23 | 0.5 | 7 | 406 | 1719 |

| NVS-642 mT ha−1 | 4.5 | 0.17 | 10 | 26 | 12 | 14 | 49 | 112 | 68 | 1.4 | 22 | 1217 | 5157 |

| ADS-24 mT ha−1 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 3.6 | 17 | 61 | 12 | 379 | 0 | 27 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 2480 | 692 |

| ADSC-72 mT ha−1 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 4.4 | 13 | 26 | 7 | 132 | 2 | 22 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 1465 | 665 |

| (b) Concentration of elements (mg kg−1) in the DTPA-TEA extract of the 0–15 cm soil layer: a 3 y average | |||||||||||||

| Control | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.25 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 11 | bdl | 0.6 | 9 | 9 |

| NVS-214 mT ha−1 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 0.04 | 1.6 | 0.31 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 10 | bdl | 0.9 | 23 | 18 |

| NVS-642 mT ha−1 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.10 | 3.5 | 0.87 | 7.2 | 10.3 | 22 | bdl | 2.0 | 22 | 37 |

| ADS-24 mT ha−1 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 3.3 | 0.32 | 13.7 | 0.2 | 11 | bdl | 0.1 | 17 | 10 |

| ADSC-72 mT ha−1 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 2.9 | 0.40 | 15.2 | 0.8 | 15 | bdl | 0.5 | 21 | 16 |

| QL (3) | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.04 | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.002 | 0.024 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| (c) Concentrations in the lettuce foliage (mg kg−1)-average of the plants from all the four seasons (5) | |||||||||||||

| Commercial (4) | 0.20 | 0.19 b | 0.14 | 0.40 | 9.6 ab | 0.71 b | 48 bc | 45 b | 68 c | 0.37 bc | 0.19 | 7200 a | 136 |

| Control | 0.16 | 0.43 ab | 0.17 | 1.02 | 5.7 c | 0.97 ab | 32 c | 48 b | 149 b | 0.47 c | 0.43 | 4485 b | 174 |

| NVS-214 mT ha−1 | 0.32 | 0.27 b | 0.19 | 0.86 | 6.6 bc | 0.76 b | 37 c | 59 a | 79 c | 0.78 ab | 0.39 | 4400 b | 158 |

| NVS-642 mT ha−1 | 0.28 | 0.41 ab | 0.20 | 1.15 | 9.0 a | 0.90 ab | 44 bc | 51 ab | 49 c | 0.67 abc | 0.40 | 5100 ab | 168 |

| ADS-24 mT ha−1 | 0.13 | 0.77 a | 0.16 | 0.62 | 5.6 bc | 1.39 a | 84 a | 49 ab | 354 a | 0.89 a | 0.48 | 6201 a | 176 |

| ADSC-72 mT ha−1 | 0.16 | 0.36 b | 0.13 | 0.91 | 5.8 bc | 0.77 b | 50 b | 47 b | 127 bc | 0.53 bc | 0.36 | 5500 a | 151 |

| Prob > F | bql | <0.0001 | bql | ns | <0.0001 | 0.01 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | ns | <0.0001 | ns |

| (d) Highest discrete concentration measured in the leachates from the lysimeters throughout the three years | |||||||||||||

| µg L−1 | mg L−1 | µg L−1 | |||||||||||

| Control | bdl | 1 | bdl | 2 | 11 | 70 | 37 | 2.1 | 3 | 5 | 17 | 0.13 | bdl |

| NVS-214 mT ha−1 | bdl | 1 | bdl | bdl | 18 | 71 | 58 | 4.6 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 0.08 | bdl |

| NVS-642 mT ha−1 | bdl | 2 | bdl | bdl | 18 | 77 | 44 | 2.0 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 0.09 | bdl |

| ADS-24 mT ha−1 | bdl | 1 | bdl | 6 | 15 | 58 | 28 | 1.8 | 6 | 12 | 16 | 0.96 | bdl |

| ADSC-72 mT ha−1 | bdl | 1 | bdl | bdl | 10 | 53 | 33 | 2.0 | 2 | 7 | 8 | 0.13 | bdl |

| WHO [51] | 10 | 3 | 10 | 50 | 2000 | 70 | - | 2.4 | 80 | - | - | - | - |

| Treatment and Load (mT h−1) | As (QL (2) = 700 µg kg−1) | Cd (QL = 40 µg kg−1) | Pb (QL = 300 µg kg−1) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | |

| Quartz sand (tap water) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 80 | 90 | 10 | 10 | 240 b | 350 bcd | 110 c | 170 bcd | 230 | 150 | 170 | 8 |

| NVS-214 | 90 | 190 | 70 | 40 | 170 b | 200 cd | 130 c | 170 bcd | 220 | 130 | 300 | bdl |

| ADSC-72 | 70 | 140 | 30 | 90 | 120 b | 210 cd | 120 c | 210 bcd | 170 | bdl | 200 | 77 |

| Quartz sand (WWE) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 150 | 150 | 160 | 40 | 600 ab | 640 abc | 1430 a | 440 b | 170 | 30 | 350 | bdl |

| NVS-214 | 150 | 150 | 200 | 60 | 370 ab | 370 bcd | 410 bc | 190 bcd | 130 | 90 | 360 | 31 |

| ADSC-72 | 80 | 130 | 230 | 80 | 310 ab | 780 ab | 580 bc | 420 bcd | bdl | bdl | 230 | 46 |

| Calcic Haploxeralf (WWE) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 40 | 20 | 140 | 20 | 100 b | 70 d | 60 d | 100 cd | 30 | 80 | 370 | 15 |

| NVS-214 | 70 | 150 | 140 | 70 | 100 b | 110 d | 70 d | 60 d | 160 | 130 | 360 | 9 |

| Non-sodic Chromic Haploxerert (WWE) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 130 | 130 | 200 | 50 | 320 ab | 200 cd | 190 c | 190 bcd | 410 | 290 | 480 | 13 |

| NVS-214 | 100 | 220 | 170 | 90 | 260 b | 270 cd | 200 c | 180 bcd | 340 | 230 | 450 | 33 |

| NVS-642 | 100 | 130 | 190 | 60 | 160 b | 270 cd | 170 c | 180 bcd | 90 | 320 | 370 | 14 |

| ADS-24 | 180 | 130 | 90 | 40 | 810 a | 980 a | 930 ab | 940 a | 350 | 80 | 210 | 15 |

| ADSC-72 | 50 | 90 | 70 | 70 | 220 b | 240 cd | 160 c | 360 bcd | 190 | 310 | 230 | 75 |

| Prob > F (3) | - | - | - | - | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Element | Control | NVS | ADS | ADSC | Prob > F | Max (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 1.0 b | 1.6 a | 1.1 b | 1.1 b | <0.0001 | 20 |

| Cd | 0.20 b | 0.22 ab | 0.21 ab | 0.22 a | <0.05 | 2 |

| Pb | 15.5 b | 16.4 a | 15.9 ab | 16.2 a | <0.05 | 100 |

| B | 35 b | 41 a | 35 b | 35 b | >0.001 | 20 |

| Cr | 34 | 35 | 35 | 35 | ns | 100 |

| Cu | 13.9 c | 15.0 bc | 16.0 ab | 17.6 a | <0.0001 | 100 |

| Fe | 18,152 | 18,156 | 18,284 | 18,208 | ns | - |

| Mn | 472 a | 459 b | 471 a | 471 a | <0.001 | 2000 |

| Ni | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | ns | 100 |

| P | 555 c | 749 ab | 638 bc | 819 a | <0.0001 | - |

| V | 40 b | 43 a | 40 b | 41 b | <0.0001 | - |

| Zn | 42 c | 46 bc | 55 ab | 59 a | <0.0001 | 250 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fine, P.; Bosak, A.; Beriozkin, A.; Shargil, D.; Mingelgrin, U.; Ben-Yephet, Y.; Kurtzman, D.; Nitzan, I.; Baram, S.; Gips, A.; et al. Phytoavailability and Leachability of Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Agricultural Soils Ameliorated with Coal Fly Ash (CFA) and CFA-Treated Biosolids. Soil Syst. 2026, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010005

Fine P, Bosak A, Beriozkin A, Shargil D, Mingelgrin U, Ben-Yephet Y, Kurtzman D, Nitzan I, Baram S, Gips A, et al. Phytoavailability and Leachability of Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Agricultural Soils Ameliorated with Coal Fly Ash (CFA) and CFA-Treated Biosolids. Soil Systems. 2026; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleFine, Pinchas, Arie Bosak, Anna Beriozkin, Dorit Shargil, Uri Mingelgrin, Yephet Ben-Yephet, Daniel Kurtzman, Ido Nitzan, Shahar Baram, Ami Gips, and et al. 2026. "Phytoavailability and Leachability of Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Agricultural Soils Ameliorated with Coal Fly Ash (CFA) and CFA-Treated Biosolids" Soil Systems 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010005

APA StyleFine, P., Bosak, A., Beriozkin, A., Shargil, D., Mingelgrin, U., Ben-Yephet, Y., Kurtzman, D., Nitzan, I., Baram, S., Gips, A., Kolokovski, T., Ovadia, A., Zipilevish, E., Zig, U., & Buchshtab, O. (2026). Phytoavailability and Leachability of Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Agricultural Soils Ameliorated with Coal Fly Ash (CFA) and CFA-Treated Biosolids. Soil Systems, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010005