Carbon Forms and Their Dynamics in Soils of the Carbon Supersite at the Black Sea Coast

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Quantitatively assess the distribution and stocks of organic and inorganic carbon in natural and anthropogenically modified sub-Mediterranean soils at the Black Sea Coast carbon supersite.

- Characterize microbial activity (e.g., microbial biomass, basal respiration, and metabolic quotient) as an indicator of carbon transformation processes in different soil types.

- Measure CO2 and CH4 fluxes using chamber techniques and determine their seasonal dynamics.

- Identify the key factors that control carbon accumulation and greenhouse gas emissions in regional carbonate soils, such as soil temperature, moisture, vegetation type, and degree of anthropogenic transformation.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

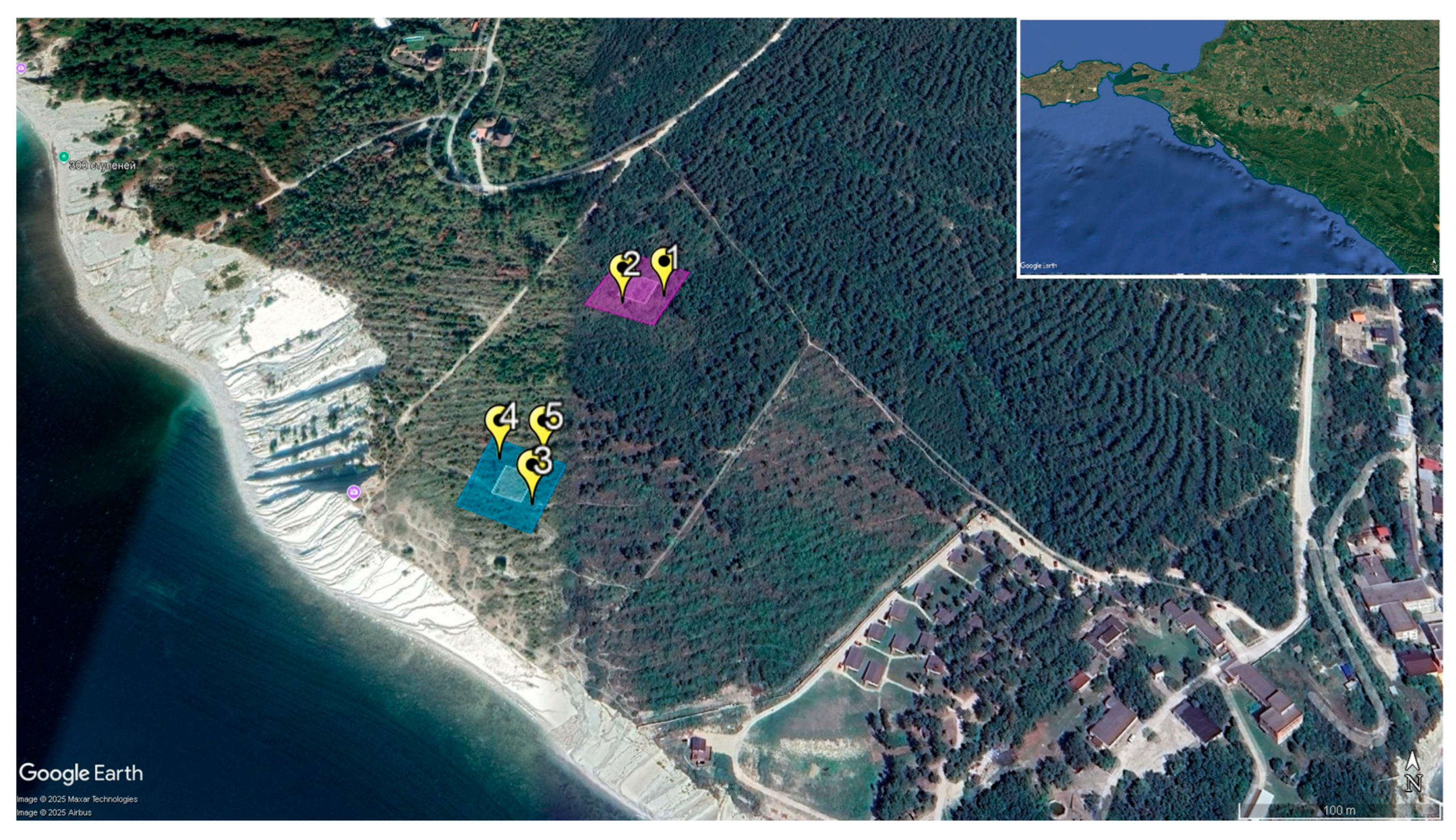

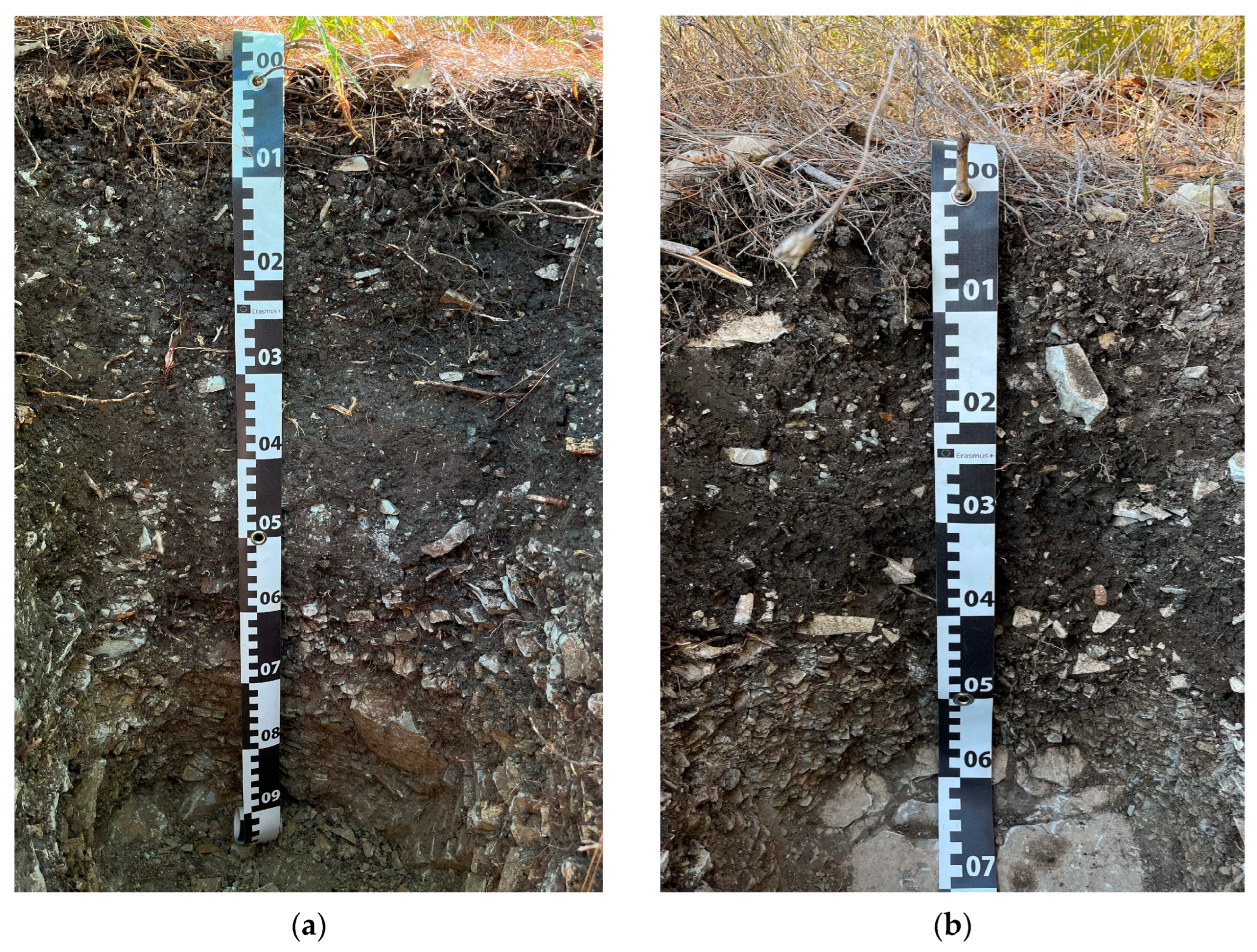

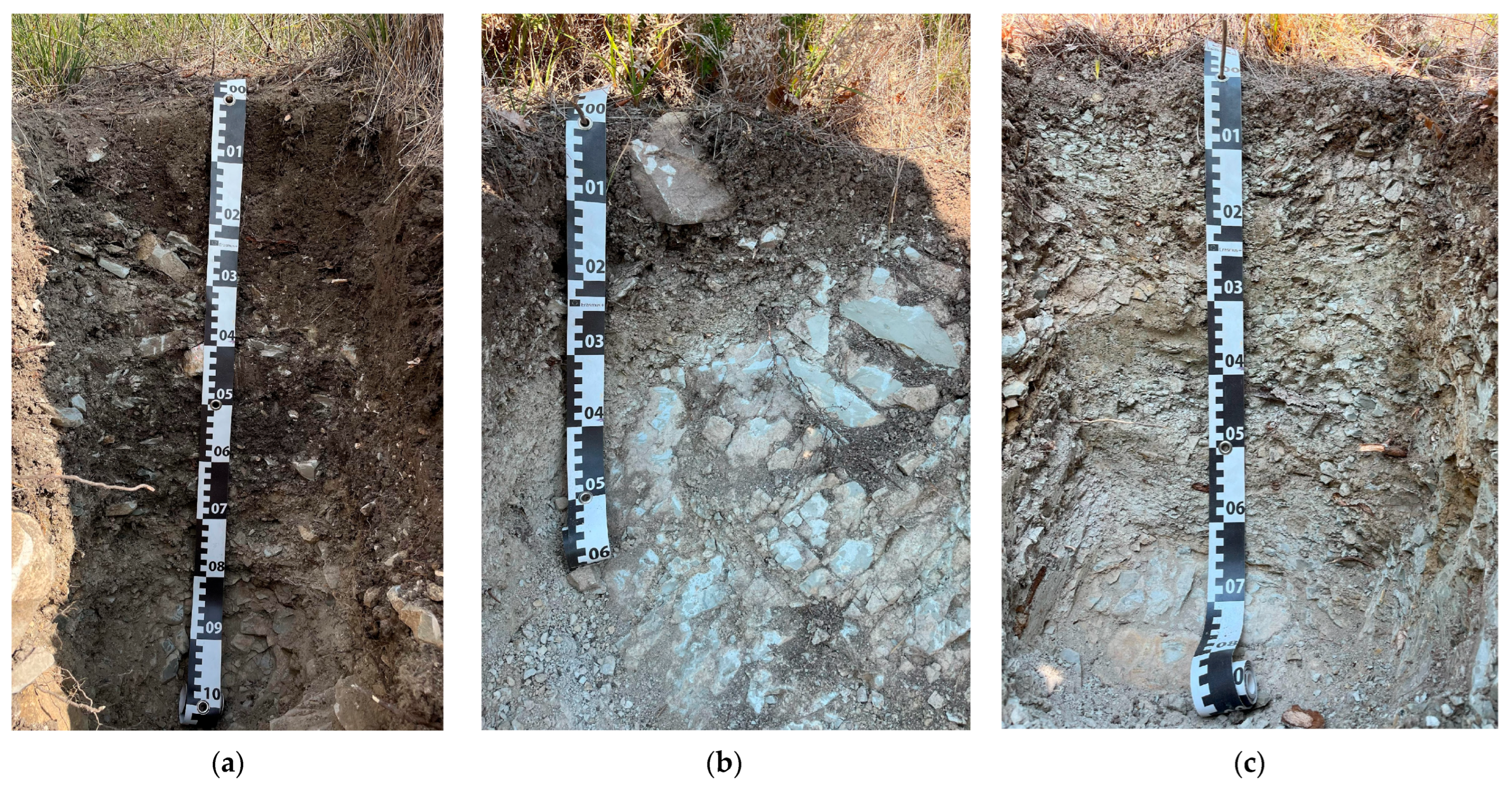

3.1. Specifics of the Carbon Supersite Soil Cover

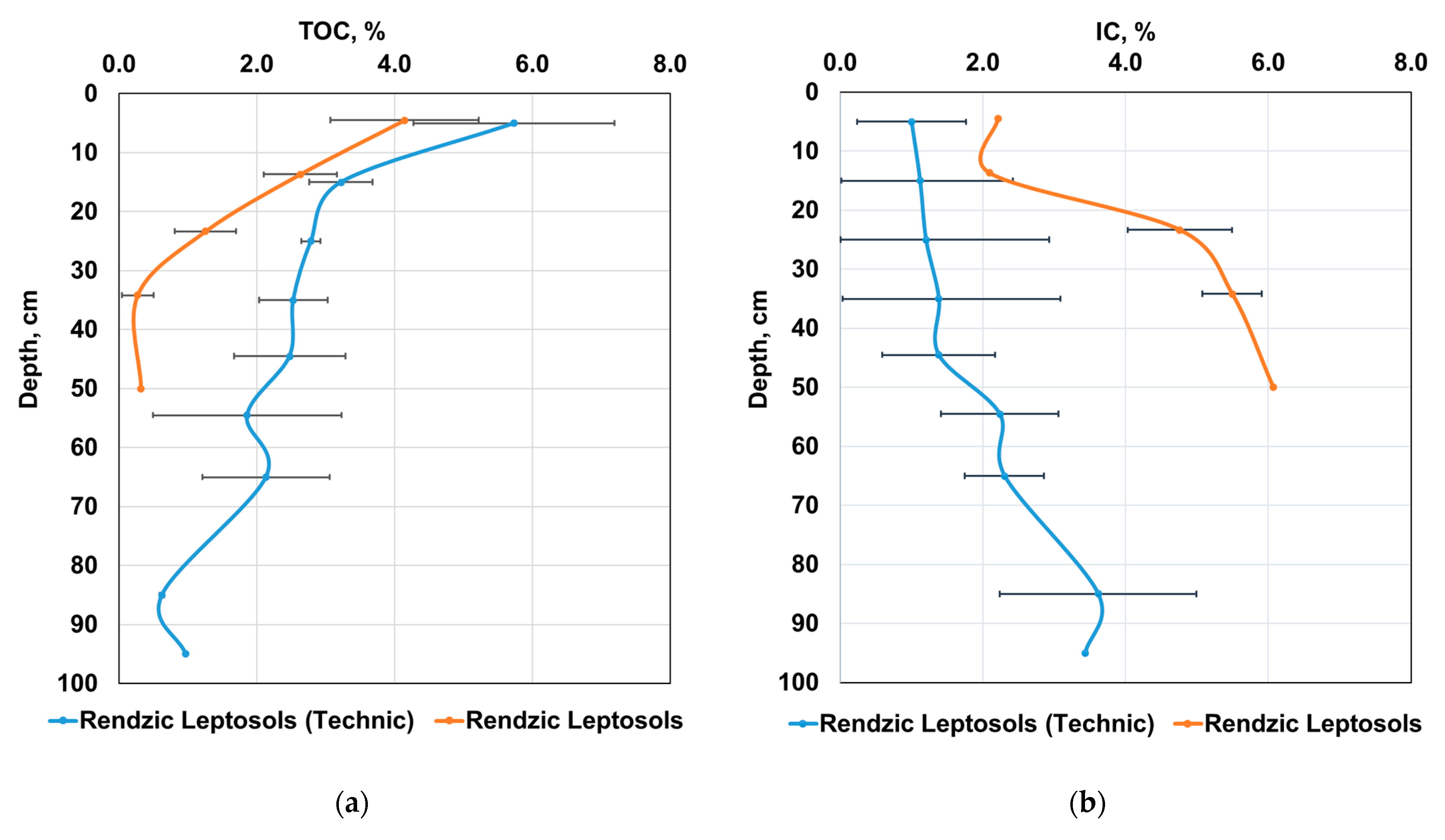

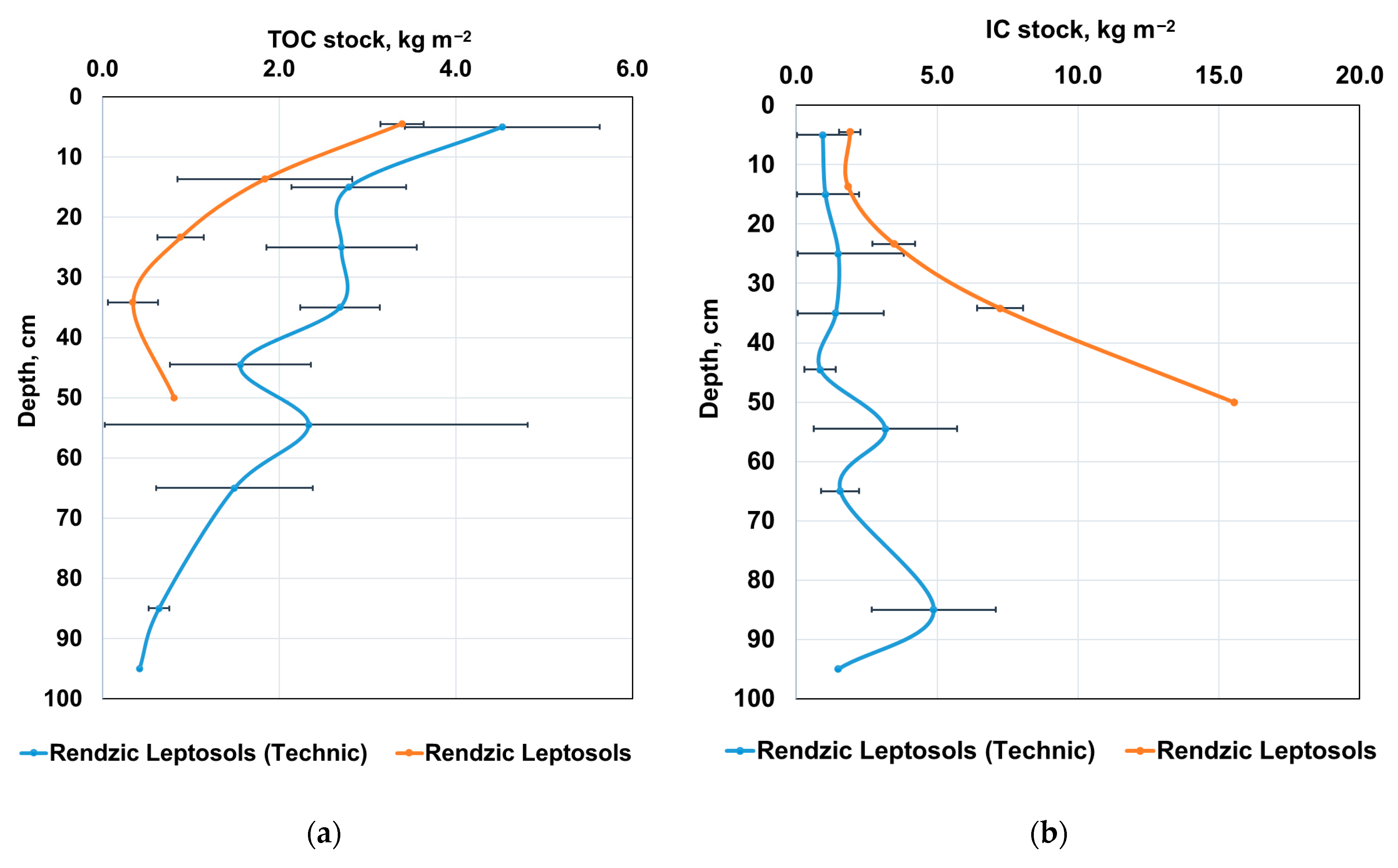

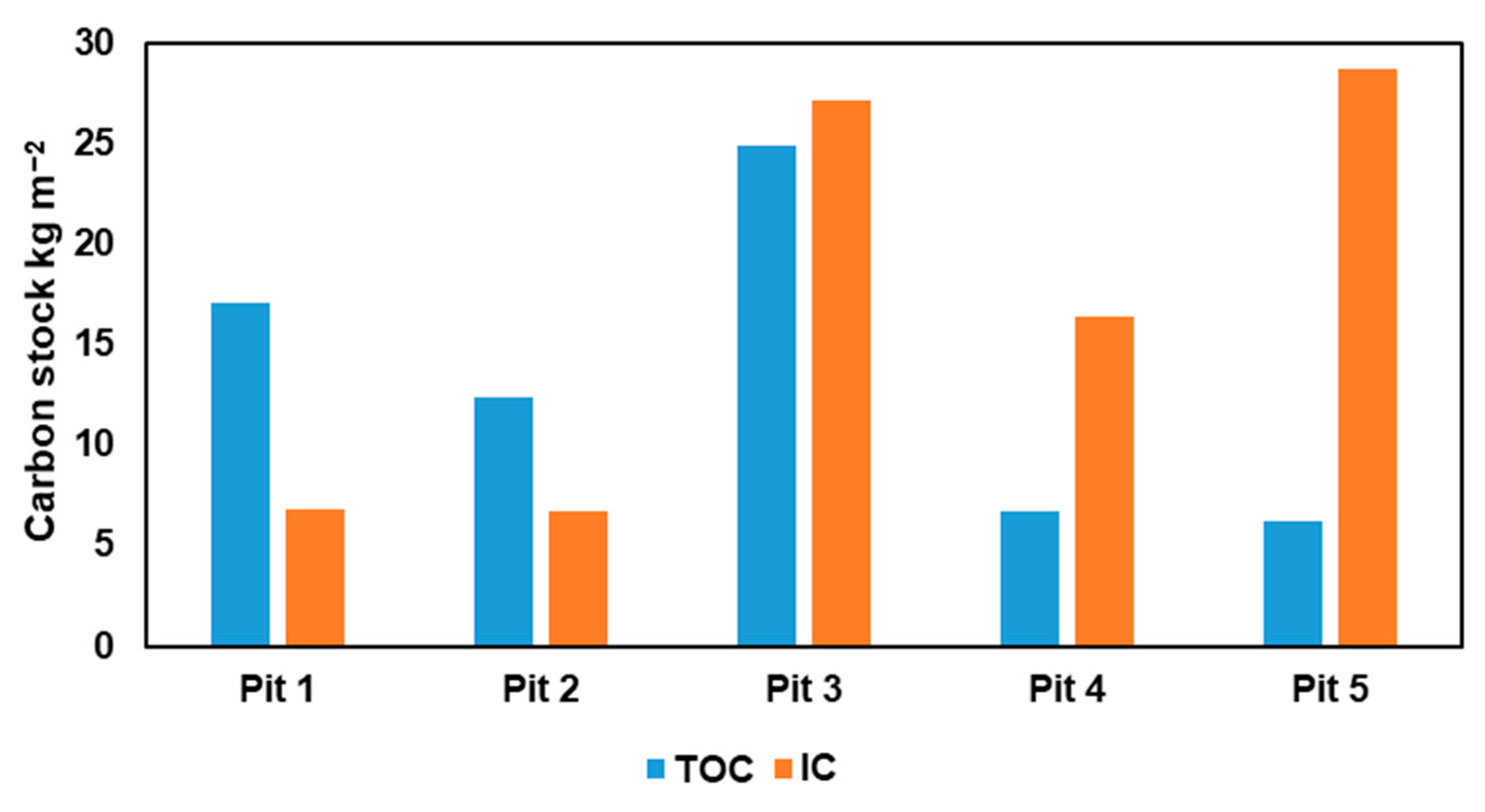

3.2. Content of Various Carbon Forms in the Carbon Supersite Soils

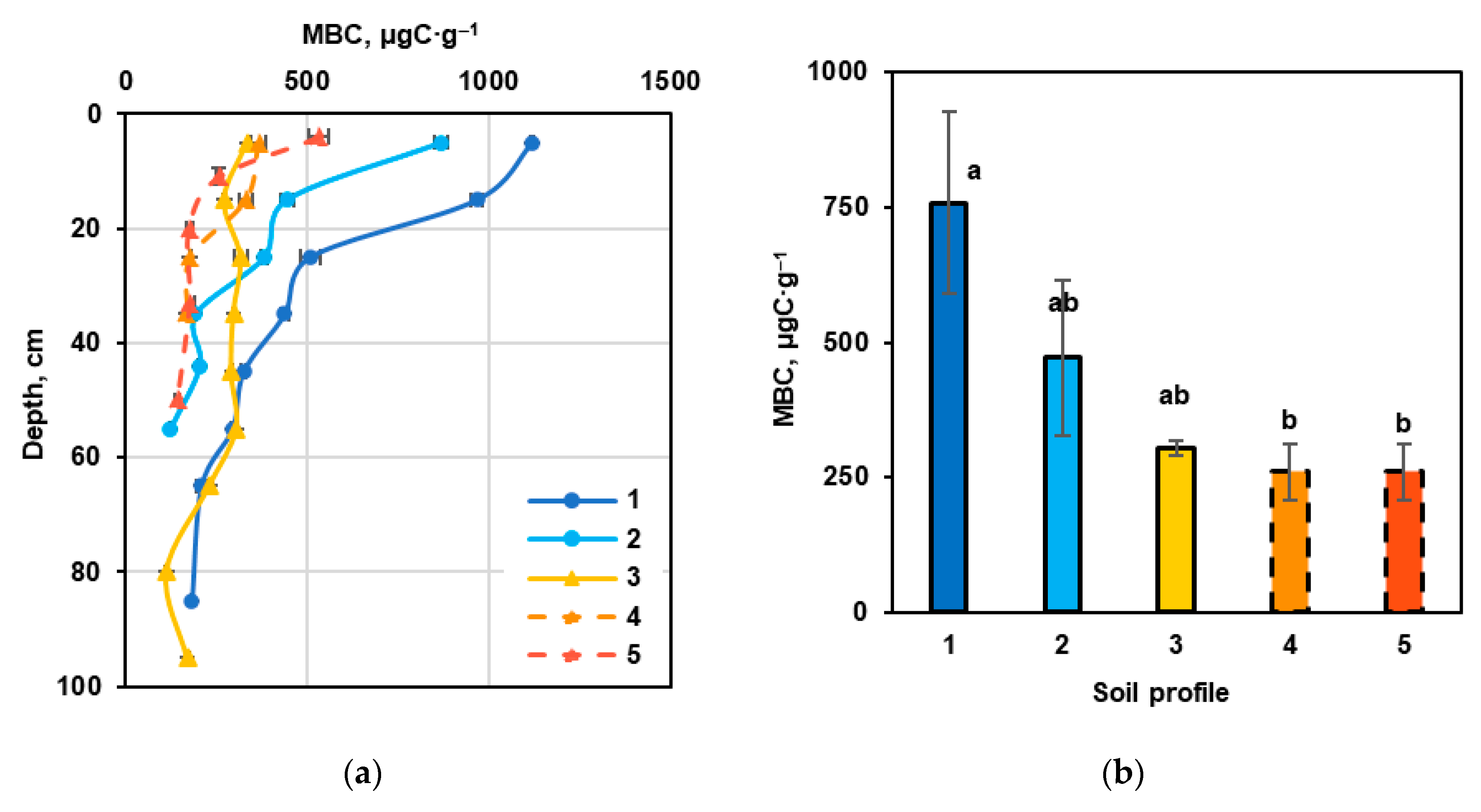

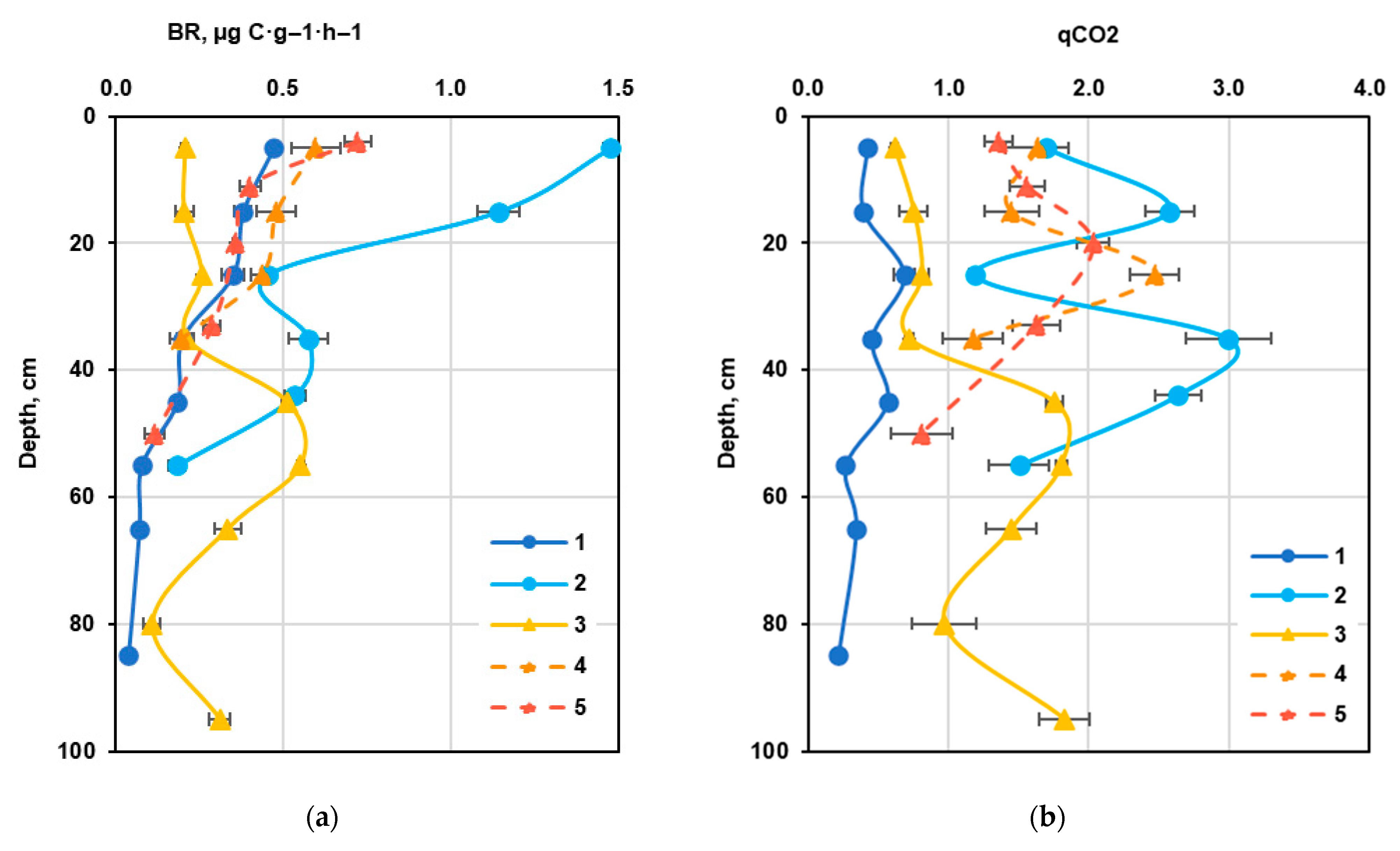

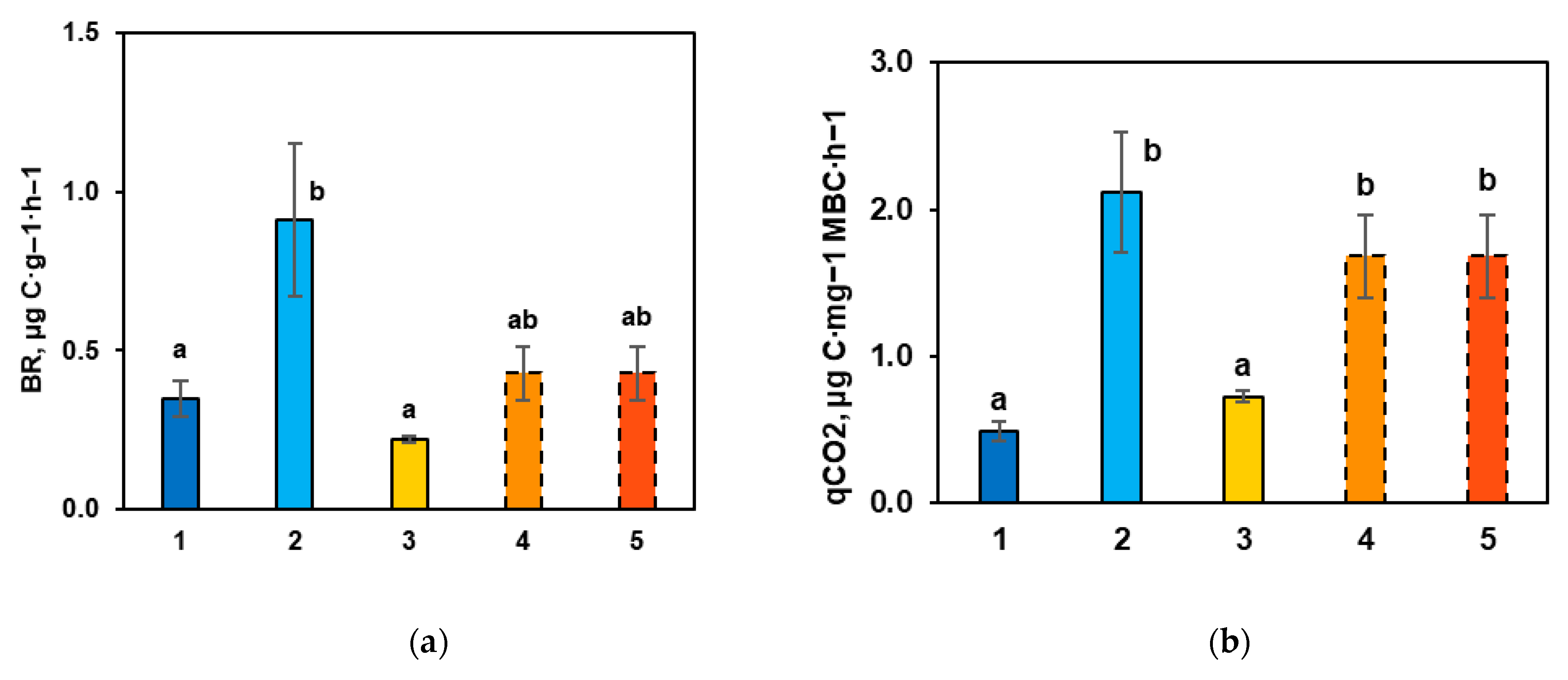

3.3. Main Microbiological Indicators of Carbon Transformation in the Carbon Supersite Soils

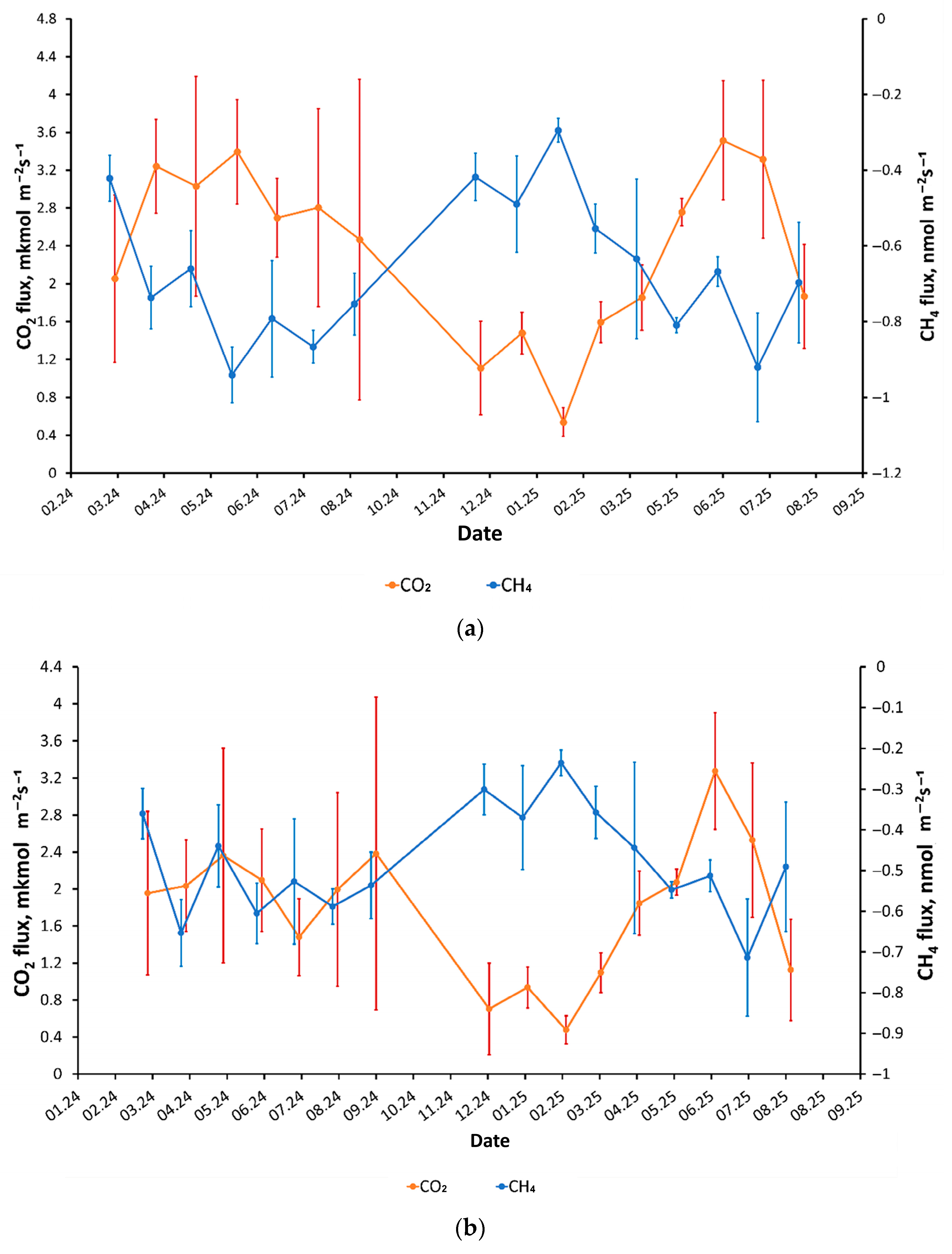

3.4. CO2 and CH4 Emission Dynamics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SB IO RAS | Southern Branch of the Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences |

| FTP | Field trial plots |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| TC | Total carbon |

| IC | Inorganic carbon |

| BD | Bulk density |

| SIR | Substrate-induced respiration |

| BR | Basal respiration |

| MBC | Microbial biomass carbon |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, N.; Kuznetsova, A.; Tikhonova, E.; Smirnov, V.; Danilova, M.; Gornov, A.; Knyazeva, S. Linking forest vegetation and soil carbon stock in Northwestern Russia. Forests 2020, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamolodchikov, D.G.; Kaganov, V.V.; Mostovaya, A.S. The effect of forest plantations on carbon dioxide emission from soils in the Volga and Don regions. Russ. J. Ecol. 2023, 54, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbov, S.N.; Minaeva, E.N.; Tagiverdiev, S.S.; Skripnikov, P.N.; Nosov, G.N.; Besuglova, O.S. Comparison of different carbonate methods for determining Calcic Chernozems. Biol. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2024, 51, S384–S394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Hayes, D. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Bakker, D.C.; Hauck, J.; Smith, S.M. Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth 2023, 15, 5301–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Zeng, J. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Forest soils and carbon sequestration. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 220, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.I.; Torn, M.S.; Abiven, S.; Dittmar, T.; Guggenberger, G.; Janssens, I.A.; Trumbore, S.E. Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 2011, 478, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batjes, N.H. Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 65, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbov, S.N.; Bezuglova, O.S.; Skripnikov, P.N.; Tishchenko, S.A. Soluble organic matter in soils of the Rostov agglomeration. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koptsik, G.N.; Koptsik, S.V.; Kupriyanova, I.V.; Kadulin, M.S.; Smirnova, I.E. Estimation of carbon stocks in soils of forest ecosystems as a basis for monitoring the climatically active substances. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.B.; Footen, P.W.; Strahm, B.D. Deep soil horizons: Contribution and importance to soil carbon pools and in assessing whole-ecosystem response to management and global change. For. Sci. 2011, 57, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyssaert, S.; Schulze, E.D.; Börner, A.; Knohl, A.; Hessenmöller, D.; Law, B.E.; Grace, J. Old-growth forests as global carbon sinks. Nature 2008, 455, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Don, A.; Schumacher, J.; Freibauer, A. Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks—A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurganova, I.; Lopes de Gerenyu, V.; Kuzyakov, Y. Carbon cost of collective farming collapse in Russia. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3781–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olchev, A.V.; Gulev, S.K. Carbon flux measurement supersites of the Russian Federation: Objectives, methodology, prospects. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2024, 60, S428–S434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakumov, E.V.; Polyakov, V.I.; Chukov, S.N. Approaches and methods for studying soil organic matter in the carbon polygons of Russia. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinskaya, S.A. Protected Nature of the Kuban; OOO KONSTANTA: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 2023; 452p, ISBN 978-5-8209-2116-2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Litvinskaya, S.A. Vegetation of the Black Sea Coast of Russia (Mediterranean Enclave); Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo: Krasnodar, Russia, 2004; 130p, ISBN 5-331-00036-3. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bobrik, A.A.; Goncharova, O.Y.; Matyshak, G.V.; Ryzhova, I.M.; Makarov, M.I.; Timofeeva, M.V. Spatial distribution of the components of carbon cycle in soils of forest ecosystems of the northern, middle, and southern taiga of western Siberia. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurganova, I.N.; Telesnina, V.M.; Lopes de Gerenyu, V.O.; Lichko, V.I.; Karavanova, E.I. The dynamics of carbon pools and biological activity of Retic Albic Podzols in southern taiga during the post-agrogenic evolution. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2021, 54, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, H.; Xie, H. A review of forest carbon cycle models on spatiotemporal scales. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Zohner, C.M.; Reich, P.B.; Liang, J.; De Miguel, S.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Ortiz-Malavasi, E. Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential. Nature 2023, 624, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryzhova, I.M.; Podvezennaya, M.A.; Telesnina, V.M.; Bogatyrev, L.G.; Semenyuk, O.V. Assessment of carbon stock and CO2 production potential for soils of coniferous-broadleaved forests. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Duborgel, M.; Gosheva-Oney, S.; González-Domínguez, B.; Brühlmann, M.; Minich, L.I.; Haghipour, N.; Hagedorn, F. Shifting carbon fractions in forest soils offset 14C-based turnover times along a 1700 m elevation gradient. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olchev, A.V. Estimation of carbon dioxide and methane emissions and absorption by land and ocean surfaces in the 21st century. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2025, 61, S74–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochkina, M.V.; Soldatkina, M.A.; Satosina, E.M.; Ilyichev, I.A.; Romanenko, V.A.; Kremenetsky, V.V.; Olchev, A.V.; Gulev, S.K. Spatial and temporal variability of carbon dioxide and methane fluxes at the soil surface in the coastal area of the carbon supersite in the Krasnodar region. Grozny Nat. Sci. Bull. 2023, 3, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sleutel, S.; De Neve, S.; Singier, B.; Hofman, G. Quantification of organic carbon in soils: A comparison of methodologies and assessment of the carbon content of organic matter. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2007, 38, 2647–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, W.R.; Robarge, W.P.; Osmond, D.L.; Heitman, J.L. Comparing four methods of measuring soil organic matter in North Carolina soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadyunina, A.F.; Korchagina, Z.A. Methods of Studying the Physical Properties of Soils, 3rd ed.; Agropromizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1986; 416p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, I.C.; Yaduvanshi, N.P.S.; Gupta, S.K. Standard Methods for Analysis of Soil, Plant and Water; Scientific Publishers: Jodhpur, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ananyeva, N.D.; Susyan, E.A.; Gavrilenko, E.G. Features of carbon determination of microbial biomass of soil by the method of substrate-induced respiration. Soil Sci. 2011, 11, 1327–1333. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.H.; Domsch, K.H. Soil microbial biomass: The eco-physiological approach. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2039–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16072-2002; Soil Quality—Laboratory Methods for Determination of Microbial Soil Respiration. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/47bffa5e-2462-4f00-95a0-e95638bf8d98/iso-16072-2002 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Skripnikov, P.N.; Gorbov, S.N.; Tagiverdiev, S.S.; Salnik, N.V.; Kozyrev, D.A.; Terekhov, I.V.; Nosov, G.N.; Melnikova, I.P. Carbon accumulation features in different functional zones of cities in the steppe zone. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitin, D.A.; Semenov, M.V.; Chernov, T.I.; Ksenofontova, I.A.; Zhelezova, A.D.; Ivanova, E.A.; Khitrov, N.B.; Stepanov, A.L. Microbiological Indicators of Soil Ecological Functions: A Review. Eurasian Soil. Sci. 2022, 55, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, P.M.; Trustrum, N.A.; DeRose, R.C. Ecosystem processes and sustainable land use in New Zealand steeplands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1992, 41, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, L.C.; Spârchez, G.; Dinca, M.; Blujdea, V.N. Organic carbon concentrations and stocks in Romanian mineral forest soils. Ann. For. Res. 2012, 55, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolák, M.; Kriaková, E.; Pichler, V.; Gömöryová, E.; Bebej, J. Isolating the soil type effect on the organic carbon content in a Rendzic Leptosol and an Andosol on a limestone plateau with andesite protrusions. Geoderma 2017, 302, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurucu, Y.; Esetlili, M.T. Rendzic Leptosols. In The Soils of Turkey; Kapur, S., Akça, E., Günal, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trustrum, N.A.; De Rose, R.C. Soil depth–age relationship of landslides on deforested hillslopes, Taranaki, New Zealand. Geomorphology 1988, 1, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond-Lamberty, B.; Thomson, A. Temperature-associated increases in the global soil respiration record. Nature 2010, 464, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zha, T.S.; Jia, X.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Qin, S.G. Soil moisture modifies the response of soil respiration to temperature in a desert shrub ecosystem. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xiao, Q.; Guo, Y.; Chen, F.; Sun, P.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, C. Soil respiration characteristics and karst carbon sink potential in woodlands and grasslands. Forests 2025, 16, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.J.; Kiese, R.; Wolf, B.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Effects of soil temperature and moisture on methane uptake and nitrous oxide emissions across three different ecosystem types. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 3205–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, Z.; Kang, X.; He, N.; Li, M. Climate warming and soil drying significantly enhance the methane uptake in China’s grasslands. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Guo, J.; Malghani, S.; Han, M.; Cao, P.; Sun, J.; Wang, W. Effects of soil moisture and temperature on microbial regulation of methane fluxes in a poplar plantation. Forests 2021, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wen, F.; Li, C.; Guan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. Methane uptake responses to heavy rainfalls co-regulated by seasonal timing and plant composition in a semiarid grassland. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1149595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depth, cm | Rockiness, (>2 mm), % | Bulk Density, g cm−3 | pH H2O | TC, % 1 | IC, % 2 | TOC, % 3 | IC Stocks, kg m−2 | TOC Stocks, kg m−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Catalytic Combustion Method | ||||||||

| Pit 1. Skeletic Rendzic Leptosols (Technic, Transportic) | ||||||||

| 0–10 | 18.9 | 0.78 | 8.1 | 8.03 | 0.62 | 7.41 | 0.39 | 4.69 |

| 10–20 | 24.7 | 1.21 | 8.6 | 4.35 | 0.62 | 3.72 | 0.57 | 3.39 |

| 20–30 | 48.3 | 1.28 | 8.3 | 3.29 | 0.36 | 2.93 | 0.24 | 1.94 |

| 30–40 | 16.8 | 1.23 | 8.4 | 3.88 | 0.78 | 3.10 | 0.80 | 3.17 |

| 40–50 | 23.6 | 1.05 | 8.8 | 3.23 | 0.85 | 2.38 | 0.68 | 1.91 |

| 50–60 | 63.7 | 1.18 | 8.5 | 3.28 | 1.62 | 1.66 | 0.69 | 0.71 |

| 60–70 | 79.7 | 2.49 | 8.8 | 2.96 | 1.75 | 1.21 | 0.89 | 0.61 |

| 70–100 | 83.0 | 2.53 | 8.9 | 2.66 | 2.07 | 0.59 | 2.68 | 0.76 |

| Pit 2. Skeletic Rendzic Leptosols (Technic, Transportic) | ||||||||

| 0–10 | 34.9 | 1.09 | 8.4 | 5.21 | 0.50 | 4.72 | 0.35 | 3.35 |

| 10–20 | 36.8 | 1.18 | 8.5 | 2.95 | 0.14 | 2.82 | 0.10 | 2.10 |

| 20–30 | 18.4 | 1.18 | 8.2 | 2.72 | 0.06 | 2.66 | 0.06 | 2.56 |

| 30–40 | 14.2 | 1.38 | 8.2 | 2.26 | 0.06 | 2.21 | 0.07 | 2.62 |

| 40–47 | 60.2 | 1.35 | 8.7 | 2.73 | 1.01 | 1.72 | 0.38 | 0.65 |

| 47–60 | 48.9 | 2.74 | 8.9 | 3.77 | 3.17 | 0.60 | 5.77 | 1.10 |

| Depth, cm | Rockiness, (>2 mm), % | Bulk Density, g cm−3 | pH H2O | TC, % | IC, % | TOC, % | IC Stocks, kg m−2 | TOC Stocks, kg m−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Catalytic Combustion Method | ||||||||

| Pit 3. Skeletic Rendzic Leptosols (Technic, Transportic) | ||||||||

| 0–10 | 3.6 | 1.13 | 8.2 | 6.96 | 1.88 | 5.08 | 2.05 | 5.54 |

| 10–20 | 19.9 | 1.15 | 8.3 | 5.73 | 2.60 | 3.13 | 2.40 | 2.88 |

| 20–30 | 34.7 | 2.00 | 8.3 | 5.96 | 3.19 | 2.77 | 4.17 | 3.62 |

| 30–40 | 49.4 | 1.98 | 8.3 | 5.59 | 3.31 | 2.28 | 3.32 | 2.28 |

| 40–50 | 46.3 | 1.19 | 8.3 | 5.62 | 2.29 | 3.33 | 1.47 | 2.13 |

| 50–60 | 30.7 | 2.26 | 8.3 | 5.23 | 1.92 | 3.32 | 3.00 | 5.19 |

| 60–70 | 48.3 | 1.50 | 8.4 | 5.92 | 2.86 | 3.06 | 2.22 | 2.38 |

| 70–90 | 66.3 | 2.23 | 8.6 | 5.05 | 4.71 | 0.35 | 7.07 | 0.52 |

| 90–100 | 76.8 | 1.88 | 8.5 | 4.40 | 3.43 | 0.97 | 1.49 | 0.42 |

| Pit 4. Rendzic Leptosols | ||||||||

| 0–10 | 4.3 | 1.07 | 8.2 | 5.30 | 2.23 | 3.07 | 2.28 | 3.15 |

| 10–20 | 20.7 | 1.13 | 8.2 | 5.25 | 2.09 | 3.16 | 1.87 | 2.83 |

| 20–30 | 49.9 | 1.53 | 8.6 | 6.30 | 5.49 | 0.81 | 4.21 | 0.62 |

| 30–40 | 12.2 | 1.55 | 8.6 | 5.95 | 5.91 | 0.04 | 8.04 | 0.06 |

| Pit 5. Skeletic Rendzic Leptosols | ||||||||

| 0–7 | 7.0 | 1.07 | 8.5 | 7.42 | 2.2 | 5.22 | 1.53 | 3.64 |

| 7–15 | 64.5 | 1.42 | 8.4 | 6.33 | 4.43 | 2.10 | 1.79 | 0.85 |

| 15–25 | 57.7 | 1.59 | 8.8 | 5.73 | 4.03 | 1.7 | 2.71 | 1.15 |

| 25–40 | 60.5 | 2.13 | 8.9 | 5.58 | 5.08 | 0.5 | 6.41 | 0.63 |

| 40–60 | 42.9 | 2.24 | 8.6 | 6.39 | 6.07 | 0.32 | 15.53 | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gorbov, S.N.; Salnik, N.V.; Tagiverdiev, S.S.; Slukovskaya, M.V.; Kochkina, M.V.; Tishchenko, S.A.; Gershelis, E.V.; Kremenetskiy, V.V.; Olchev, A.V. Carbon Forms and Their Dynamics in Soils of the Carbon Supersite at the Black Sea Coast. Soil Syst. 2026, 10, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010004

Gorbov SN, Salnik NV, Tagiverdiev SS, Slukovskaya MV, Kochkina MV, Tishchenko SA, Gershelis EV, Kremenetskiy VV, Olchev AV. Carbon Forms and Their Dynamics in Soils of the Carbon Supersite at the Black Sea Coast. Soil Systems. 2026; 10(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorbov, Sergey N., Nadezhda V. Salnik, Suleiman S. Tagiverdiev, Marina V. Slukovskaya, Margarita V. Kochkina, Svetlana A. Tishchenko, Elena V. Gershelis, Vyacheslav V. Kremenetskiy, and Alexander V. Olchev. 2026. "Carbon Forms and Their Dynamics in Soils of the Carbon Supersite at the Black Sea Coast" Soil Systems 10, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010004

APA StyleGorbov, S. N., Salnik, N. V., Tagiverdiev, S. S., Slukovskaya, M. V., Kochkina, M. V., Tishchenko, S. A., Gershelis, E. V., Kremenetskiy, V. V., & Olchev, A. V. (2026). Carbon Forms and Their Dynamics in Soils of the Carbon Supersite at the Black Sea Coast. Soil Systems, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010004