The Efficacy of MSC-Derived Exosome-Based Therapies in Treating Scars, Aging and Hyperpigmentation: A Systematic Review of Human Clinical Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

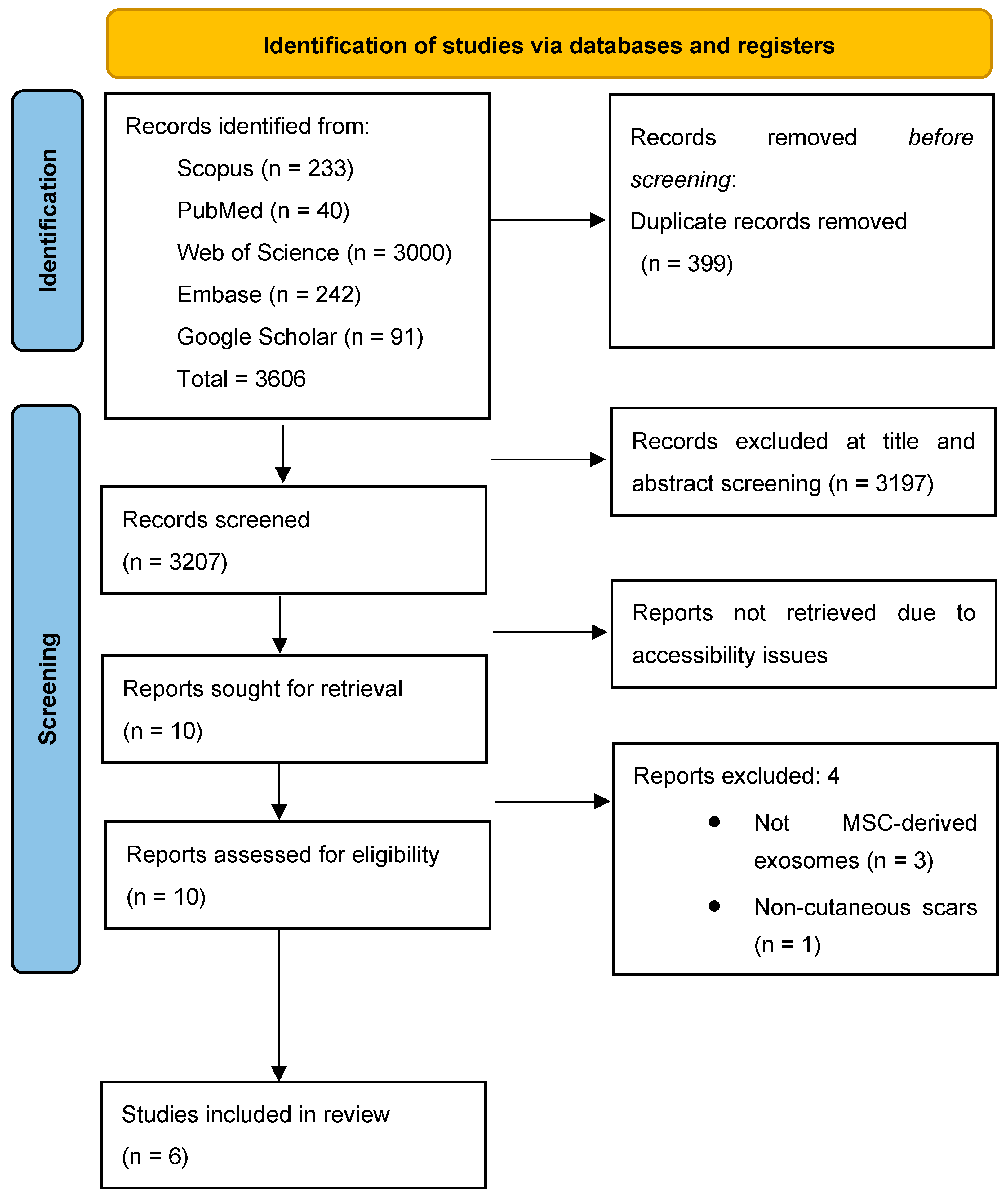

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.3. MSC-Exosomes Characteristics

4. Efficacy

4.1. Efficacy in Scar Thickness

4.2. Efficacy in Hyperpigmentation

4.3. Efficacy in Wrinkles, Elasticity, and Hydration

5. Pain

6. Safety

6.1. Adverse Effects

6.2. Recurrence

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| MSC-Exos | Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes |

| MSC-EVs | Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Extracellular Vesicles |

| ADSC | Adipose tissue-derived Stem Cell |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practice |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| MudPIT | Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology |

| ECCA | Échelle d’Évaluation Clinique des Cicatrices d’Acné |

| GAIS | Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale |

| IGA | Investigator Global Assessment |

| RoB 2 | Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool |

| MINORS | Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies |

| NTA | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis |

References

- Wang, Y.; Bai, W.; Wang, X. Progress on Three-Dimensional Visualizing Skin Architecture with Multiple Immunofluorescence Staining and Tissue-Clearing Approaches. Histol. Histopathol. 2025, 40, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.S.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, W.-S.; Choi, Y.-J.; Yoo, K.H. A Narrative Review of Scar Formation. Med. Lasers 2023, 12, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, S.-M.; Heljasvaara, R.; Gullberg, D.; Tasanen, K.; Pihlajaniemi, T. Toward Understanding Scarless Skin Wound Healing and Pathological Scarring. F1000Research 2019, 8, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansory, A.S.; Alhamdany, Z.S. Multimodality Management of Skin Hyperpigmentation. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025, 49, 3776–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaccio, F.; D’Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Bellei, B. Focus on the Contribution of Oxidative Stress in Skin Aging. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.H.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, J.; Park, B.C.; Park, K.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Bae, Y.; Park, G.-H. Combination Treatment with Human Adipose Tissue Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Fractional CO2 Laser for Acne Scars: A 12-Week Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized, Split-Face Study. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2020, 100, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikdoust, F.; Pazoki, M.; Mohammadtaghizadeh, M.; Karimzadeh Aghaali, M.; Amrovani, M. Exosomes: Potential Player in Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2022, 22, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Dukharan, V.; Broughton, L.; Stegura, C.; Schur, N.; Samman, L.; Schlesinger, T. Exosomes for Aesthetic Dermatology: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Update. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e16766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernoff, G. The utilization of human placental fetal MSC-derived exosomes in treating keloid scars. J. Surg. 2022, 7, 1482. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, M.; Shivananjappa, S. Topical human MSC-derived exosomes for wound healing after aesthetic procedures: A case series. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2024, 23, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.H.; Kwon, H.H.; Seok, J.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, J.; Park, B.C.; Shin, E.; Park, K.Y. Efficacy of combined treatment with human adipose tissue stem cell-derived exosome-containing solution and microneedling for facial skin aging: A 12-week prospective, randomized, split-face study. J. Cosmet Dermatol. 2023, 22, 3418–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana-López, S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Treatment for Acne Scars: An Alternative Therapy. J. Stem Cell Res. 2024, 5, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.S.; Lee, J.; Won, Y.; Duncan, D.I.; Jin, R.C.; Lee, J.; Kwon, H.H.; Park, G.-H.; Yang, S.H.; Park, B.C.; et al. Skin Brightening Efficacy of Exosomes Derived from Human Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem/Stromal Cells: A Prospective, Split-Face, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimera Labs. Exosome Biotechnology Laboratory. 2023. Available online: https://www.kimeralabs.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- ExoCoBio. Exosome-Based Regenerative Medicine. 2024. Available online: http://www.exocobio.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Busatto, S.; Vilanilam, G.; Ticer, T.; Lin, W.-L.; Dickson, D.W.; Shapiro, S.; Bergese, P.; Wolfram, J. Tangential Flow Filtration for Highly Efficient Concentration of Extracellular Vesicles from Large Volumes of Fluid. Cells 2018, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visan, K.S.; Lobb, R.J.; Ham, S.; Lima, L.G.; Palma, C.; Edna, C.P.Z.; Wu, L.; Gowda, H.; Datta, K.K.; Hartel, G.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Tangential Flow Filtration and Ultracentrifugation, Both Combined with Subsequent Size Exclusion Chromatography, for the Isolation of Small Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicle 2022, 11, 12266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auger, C.; Brunel, A.; Darbas, T.; Akil, H.; Perraud, A.; Bégaud, G.; Bessette, B.; Christou, N.; Verdier, M. Extracellular Vesicle Measurements with Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: A Different Appreciation of Up and Down Secretion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Du, L. Review on Strategies and Technologies for Exosome Isolation and Purification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 811971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comfort, N.; Cai, K.; Bloomquist, T.R.; Strait, M.D.; Ferrante, A.W., Jr.; Baccarelli, A.A. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis for the Quantification and Size Determination of Extracellular Vesicles. JoVE 2021, 62447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCEplus Technology. The Technology of ASCE+ and EXOSOME. 2025. Available online: https://www.asceplus.com/technology (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Skin & Laser. Laser and Aesthetic Treatments. 2024. Available online: https://franklinlaser.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Cellgenic. Regenerative Medicine Exosome Products. 2025. Available online: https://cellgenic.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Yuan, T.; Meijia, L.; Xinyao, C.; Xinyue, C.; Lijun, H. Exosome Derived from Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Improve Wound Healing Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Animal Studies. Int. Wound J. 2023, 20, 2424–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, H.; Xue, Z.; Tang, H.; Chen, X.; Liao, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles and Apoptotic Extracellular Vesicles for Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Studies. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, H.S.; Riau, A.K.; Yam, G.H.-F.; Yusoff, N.Z.B.M.; Han, E.J.Y.; Goh, T.-W.; Lai, R.C.; Lim, S.K.; Mehta, J.S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes as Immunomodulatory Therapy for Corneal Scarring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population: Human participants of any age/gender with cutaneous skin conditions such as scars, aging and hyperpigmentation | Studies will be excluded if they involve non-human subjects, including in vitro (lab-based) or animal models. |

| Studies will be considered if they assess the use of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosome therapies, delivered either topically or via injection, for the purpose of scar treatment. | Articles will also be excluded if they involve non-cutaneous scars, such as scarring of internal organs (e.g., cardiac, liver, or lung fibrosis). |

| Studies reporting at least one clinical outcome related to scar improvement, Pigmentation improvement, Anti-aging effects (e.g., texture, thickness, pigmentation, wrinkle depth, melanin index and patient satisfaction). | Outcomes: Studies not reporting clinical outcomes related to scar healing, Pigmentation improvement, Anti-aging effects |

| Study Design: Clinical trials (randomized or non-randomized), cohort studies, case series, or case reports, Pilot study. | Study Design: Reviews, editorials, opinion papers, protocols, or conference abstracts without full text. |

| Language: Articles published in English. | Language: Articles not published in English. |

| Publication Date: Articles published from 2010 to 2025. | Any studies that utilize non-MSC-derived exosomes (e.g., platelet-derived or tumor-derived exosomes) |

| Study | Particle Size (Reported) | Quantification (Particles/mL) | Positive Markers | Negative Markers | Purity/Isolation Description (Reported) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chernoff et al., 2022 [14] | Peak ~120–130 nm (according to manufacturer) | 5 billion exosomes in 5 mL (initial); additional 3 billion exosomes (1.0 mL) for first 3 weeks | N/A | N/A | Isolation not explicitly described in paper; manufacturer reports proprietary serial purification and Beckman ultracentrifuge |

| Kwon et al., 2020 [7] | Mode ~117 nm (measured via NTA) | 3.26 × 1011 particles/mL (NTA); clinical doses: 9.78 × 1010 and 1.63 × 1010 particles/mL | CD9, CD63, CD81 (bead-based flow cytometry) | Low calnexin and cytochrome C | ExoSCRT™; 0.2 μm filtration then tangential-flow filtration (500 kDa MWCO) |

| Peredo et al., 2024 [15] | N/A | 2–5 × 109 and 4.8 × 109 particles/mL | N/A | N/A | Exovex™ processed under GMP with QC testing (NTA, NGS, MudPIT) |

| Park et al., 2023 [16] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ExoSCRT™ platform mentioned. |

| Pastrana-López, 2024 [17] | N/A | 3 × 1010 particles/unspecified | N/A | N/A | Isolation method: N/A/Not stated in paper; delivery: infiltration with 25 G cannula + subcision |

| Cho et al., 2020 [18] | 30–200 nm | 1.47 × 1012 particles/mL isolated -clinical dose not specified | CD9, CD63, CD81 | calnexin | tangential flow filtration (TFF) using a 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane cartridge with phosphate-buffered saline |

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Country | Journal | Study Design | Participants (N) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Participants | Female | Male | ||||

| Chernoff, 2022 [14] | United States | Journal of Surgery | pilot study | 21 | 11 | 10 |

| Kwon, 2020 [7] | Republic of Korea | Acta Dermato-Venereologica | Randomized Controlled Trials | 25 | 7 | 18 |

| Peredo, 2024 [15] | United States | Journal of Drugs in Dermatology | Case Series | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Park, 2023 [16] | Republic of Korea | Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology | prospective, randomized, split-face, comparative study | 28 | 20 | 8 |

| Pastrana-López, 2024 [17] | México | Journal of Stem Cell Research | Case Report | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Cho, 2020 [18] | Republic of Korea | Cosmetics | Prospective, split-face, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled study | 21 | 21 | 0 |

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Range of Age (Years) | Skin Condition (Scar, Aging, Hyperpigmentation) |

|---|---|---|

| Chernoff, 2022 [14] | 23–57 | Keloid scar |

| Kwon, 2020 [7] | 19–54 | Atrophic acne scars |

| Peredo, 2024 [15] | 31–72 | Acne, melasma, aging, dog bite trauma |

| Park, 2023 [16] | 43–66 | Facial aging (features: wrinkles, elasticity loss, irregular pigmentation) |

| Pastrana-López, 2024 [17] | 33 year-old female patient | Severe acne scars (boxcar, rolling scars) and hyperpigmentation. |

| Cho, 2020 [18] | 39–55 | Hyperpigmentation (focused on melanin reduction and skin brightening). |

| Study ID (Author, Year) | 1. A Clearly Stated Aim | 2. Inclusion of Consecutive Patients | 3. Prospective Collection of Data | 4. Endpoints Appropriate to the Aim of the Study | 5. Unbiased Assessment of the Study Endpoint | 6. Follow-Up Period Appropriate to the Aim of the Study | 7. Loss to Follow Up Less than 5% | 8. Prospective Calculation of the Study Size | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chernoff 2022 [14] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

| Peredo 2024 [15] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

| Study ID | Concentration of Exosome | Isolation Method | Source of Exosome | Exosome Delivery Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chernoff, 2022 [14] | 1 × 109 particles/mL | GMP-certified tangential-flow filtration (TFF) process | Human placental, fetal mesenchymal stem cells (XoGlo) | Direct injection into wound base |

| Kwon, 2020 [7] | 9.78 × 1010 particles/mL | ExoSCRT™, Exosomes were isolated from ASC-conditioned medium using filtration and tangential-flow purification, then quantified by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). | Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Topical gel applied immediately post-laser and twice daily for 2 days post-treatment |

| Peredo, 2024 [15] | 2–5 × 109 and 4.8 × 109 particles/mL | Exovex™, Processed under GMP with QC testing (NTA, NGS, MudPIT) | Human placental mesenchymal stem cells | Topical application (Cases 1, 2); slow topical delivery using 32 G needle (Case 3) |

| Park, 2023 [16] | N/A | ExoSCRT™ | Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Step 1: Microneedling (1.0 mm depth) performed first to create microchannels. Step 2: 2 mL of HACS (exosome solution) applied topically immediately after microneedling to the treatment side. |

| Pastrana-López, 2024 [17] | 1 × 1010 particles/mL | N/A | Derived from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly | Infiltration with a 25 G cannula into the deep dermal plane. Combined with subcision for mechanical release of fibrous bands. |

| Cho, 2020 [18] | 1.47 × 1012 particles/mL isolated however clinical dose used not specified | Exosomes were isolated from cultured ASCs using tangential flow filtration, stored at −80 °C, and characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis | Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Topical application (cosmetic formulation: gel with glycerin, xanthan gum, Carbopol 344) |

| Study ID | Outcomes | Adverse Effects | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Side Outcome | Control Side Outcome | |||

| Chernoff, 2022 [14] | 18 out of 21 patients had no recurrence of keloid scars over a 2-year follow-up period. | N/A | No adverse effects were reported. | 1. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurred in Fitzpatrick skin types III–VI. 2. Clinical results suggest exosome therapy may reduce keloid recurrence. |

| Kwon, 2020 [7] | 32.5% Reduction | 19.9% Reduction | No scarring or permanent adverse effects were reported. | 1. Better Global Assessment:

|

| Peredo, 2024 [15] | Rapid healing, reduced swelling, erythema, pain, scarring across all cases | N/A | No adverse effects were reported. |

|

| Park, 2023 [16] | Wrinkles: improved by 12.4%, 14.4%, and 13.4% (p < 0.05), Elasticity: Increased by 11.3% (p = 0.002), Hydration: Rose by 6.5% (p = 0.037), Melanin index dropped by 9.9% (p = 0.044) | Wrinkles: decreased by 6.6%, 6.8%, and 7.1%, Elasticity: Declined by 3.3%, Hydration Increased by 4.5%, Melanin index reduced by 1.0% | Mild erythema, temporary swelling, minor bleeding resolved quickly, no serious adverse effects. | 1. The Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) score was significantly higher on the exosome treated side than on the control side at the final follow-up visit (p = 0.005). 2. Superior Anti-Aging Effects: xosome + microneedling significantly improved wrinkles, elasticity, hydration, and pigmentation compared to saline control. 3. Histological Confirmation:-Increased collagen, elastic fibers, and mucin in treated skin, supporting clinical results. |

| Pastrana-López, 2024 [17] | Significant improvement in skin appearance; ECCA score decreased from 180 to 90 points; regeneration of scar tissue; improved skin texture and color. | no control group | No adverse effects were reported. | 1. Scar Type-Specific Results: -Ice-pick scars: Complete resolution -Boxcar/Rolling scars: Partial improvement 2. Hyperpigmentation Reduction -Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation: Significant clearance 3. Subjective Outcomes -Implied Satisfaction: Patient reported “significant disappearance of acne” |

| Cho, 2020 [18] | Statistically significant reduction in melanin levels compared to placebo control, starting from 2 weeks with peak efficacy at 4 weeks | No significant reduction in melanin levels compared to the intervention side. | No adverse effects were observed in any volunteer during or after the study. | 1. The effect was more pronounced in volunteers aged < 50 years. 2. Melanin reduction was transient, diminishing by 8 weeks, suggesting limited long-term efficacy. |

| Study (First Author, Year) | Follow-Up Duration | Reported Adverse Events | Severity/Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chernoff, 2022 [14] | 2 years | No adverse effects reported | No treatment-related complications |

| Kwon, 2020 [7] | 12 weeks (6-week post-final assessment) | Pain, erythema, edema, dryness | Common, transient, resolved without sequelae |

| Peredo, 2024 [15] | Up to 10 days (case-based, short-term) | No adverse effects reported | No safety concerns noted |

| Park, 2023 [16] | 6 weeks after last treatment | Mild erythema, swelling, petechiae | Self-limiting, resolved spontaneously |

| Pastrana-López, 2024 [17] | 45–60 days between sessions (clinical follow-up) | No adverse effects reported | No complications observed |

| Cho, 2020 [18] | 8 weeks | No adverse effects observed in any participant | No local or systemic adverse reactions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Shammrie, F.F.; Alhemshy, L.Z.; Althawy, M.M.; Alfaraj, M.M.; Alotaibi, A.S.; Alali, D.S.; Alsaggaf, O.H.; Alhamashi, L.Z.; Albelowi, L.M. The Efficacy of MSC-Derived Exosome-Based Therapies in Treating Scars, Aging and Hyperpigmentation: A Systematic Review of Human Clinical Outcomes. Reports 2025, 8, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040268

Al Shammrie FF, Alhemshy LZ, Althawy MM, Alfaraj MM, Alotaibi AS, Alali DS, Alsaggaf OH, Alhamashi LZ, Albelowi LM. The Efficacy of MSC-Derived Exosome-Based Therapies in Treating Scars, Aging and Hyperpigmentation: A Systematic Review of Human Clinical Outcomes. Reports. 2025; 8(4):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040268

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Shammrie, Fawwaz F., Lama Z. Alhemshy, Maitha M. Althawy, Maryam M. Alfaraj, Aseel S. Alotaibi, Danah S. Alali, Omar H. Alsaggaf, Layan Z. Alhamashi, and Lama M. Albelowi. 2025. "The Efficacy of MSC-Derived Exosome-Based Therapies in Treating Scars, Aging and Hyperpigmentation: A Systematic Review of Human Clinical Outcomes" Reports 8, no. 4: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040268

APA StyleAl Shammrie, F. F., Alhemshy, L. Z., Althawy, M. M., Alfaraj, M. M., Alotaibi, A. S., Alali, D. S., Alsaggaf, O. H., Alhamashi, L. Z., & Albelowi, L. M. (2025). The Efficacy of MSC-Derived Exosome-Based Therapies in Treating Scars, Aging and Hyperpigmentation: A Systematic Review of Human Clinical Outcomes. Reports, 8(4), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040268