Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Case Report in a Grade 2 Maternity and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

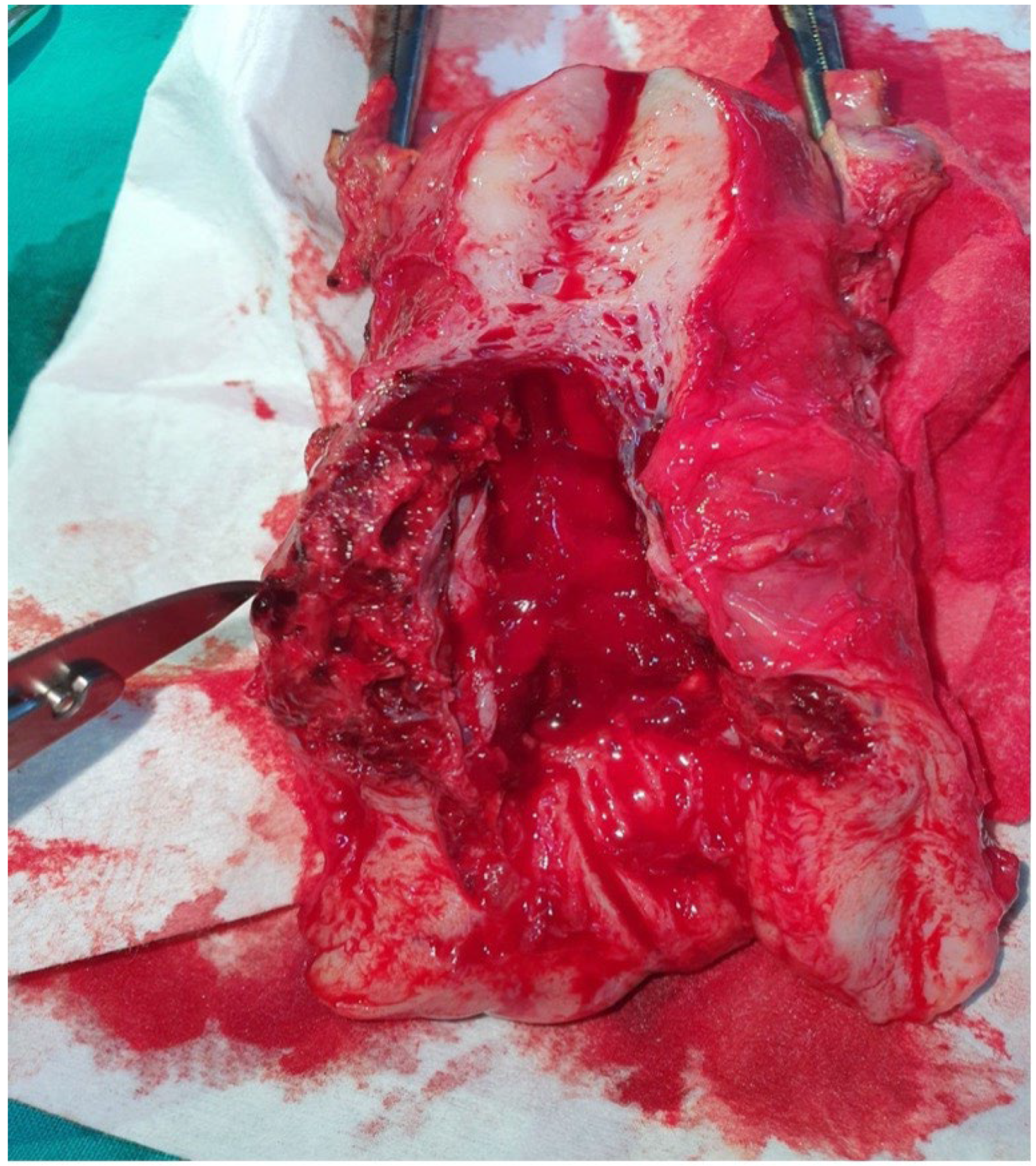

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angolile, C.M.; Max, B.L.; Mushemba, J.; Mashauri, H.L. Global Increased Cesarean Section Rates and Public Health Implications: A Call to Action. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanisoglu, S.; Engin-Ustun, Y.; Karatas Baran, G.; Kurumoglu, N.; Keskinkilic, B. Use of Ten-Group Robson Classification in Türkiye to Discuss Cesarean Section Trends. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 75, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keag, O.E.; Norman, J.E.; Stock, S.J. Long-Term Risks and Benefits Associated with Cesarean Delivery for Mother, Baby, and Subsequent Pregnancies: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS Med. 2018, 15, e1002494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, C.; Young, B.K. Cesarean Section One Hundred Years 1920–2020: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. J. Perinat. Med. 2021, 49, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Monteagudo, A.; Calì, G.; D’Antonio, F.; Kaelin Agten, A. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Patient Counseling and Management. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 46, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, F.; Schiattarella, A.; D’Urso, G.; Vitale, S.G.; Carugno, J.; Verzì, G.; D’Urso, V.; Iacono, E.; Siringo, S.; Leanza, V.; et al. Impact of Hysterotomy Closure Technique on Subsequent Cesarean Scar Defects Formation: A Systematic Review. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2023, 88, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberkt, C.; Lemmers, M.; De Vries, R.; Stegwee, S.I.; De Leeuw, R.A.; Huirne, J.A.F. Aetiology, Risk Factors and Preventive Strategies for Niche Development: A Review. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 90, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budny-Wińska, J.; Zimmer-Stelmach, A.; Pomorski, M. Impact of Selected Risk Factors on Uterine Healing After Cesarean Section in Women with Single-Layer Uterine Closure: A Prospective Study Using Two- and Three-Dimensional Transvaginal Ultrasonography. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 31, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomorski, M.; Fuchs, T.; Rosner-Tenerowicz, A.; Zimmer, M. Morphology of the Cesarean Section Scar in the Non-Pregnant Uterus after One Elective Cesarean Section. Ginekol. Pol. 2017, 88, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberkt, C.; Stegwee, S.I.; Van Der Voet, L.F.; Van Baal, W.M.; Kapiteijn, K.; Geomini, P.M.A.J.; Van Eekelen, R.; de Groot, C.J.; de Leeuw, R.A.; Huirne, J.A.; et al. Single-Layer vs Double-Layer Uterine Closure During Cesarean Delivery: 3-Year Follow-Up of a Randomized Controlled Trial (2Close Study). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 346.e1–346.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Monteagudo, A.; Calì, G.; D’Antonio, F.; Kaelin Agten, A. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Pathogenesis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 46, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Tritsch, I.; Buca, D.; Di Mascio, D.; Cali, G.; D’Amico, A.; Monteagudo, A.; Tinari, S.; Morlando, M.; Nappi, L.; Greco, P.; et al. Outcome of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy According to Gestational Age at Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 258, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, N.; Kyozuka, H.; Fukuda, T.; Murata, T.; Kanno, A.; Yasuda, S.; Yamaguchi, A.; Sekine, R.; Hata, A.; Fujimori, K. Late-Diagnosed Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Resulting in Unexpected Placenta Accreta Spectrum Necessitating Hysterectomy. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2020, 66, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.; Viana Pinto, P.; Costa, M.A. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Systematic Review on Expectant Management. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 288, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM); Miller, R.; Gyamfi-Bannerman, C.; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, B9–B20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, G.; Vona, L.; Carlucci, S.; Zullo, F.; Laganà, A.S.; Etrusco, A.; Restaino, S.; Nappi, L. Conservative Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with the Combination of Methotrexate and Mifepristone: A Systematic Review. Womens Health 2024, 20, 17455057241290424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagli, F.; Dolanbay, M.; Gülseren, V.; Kütük, S.; Aygen, E.M. Is Local Methotrexate Therapy Effective in the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy? A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Kaelin Agten, A.; Monteagudo, A.; Calì, G.; D’Antonio, F. The Use of Pressure Balloons in the Treatment of First Trimester Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 91, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadio, P.; Ambrosio, M.; Verrelli, L.; Salucci, P.; Arena, A.; Seracchioli, R. Conservative Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Treatment: Local Methotrexate Injection Followed by Hysteroscopic Removal with Hysteroscopic Tissue Removal System. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1417–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch Petersen, K.; Hoffmann, E.; Rifbjerg Larsen, C.; Nielsen, H.S. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Treatment Studies. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, D.; Yang, L.; Jing, X.; Kong, X.; Chen, D.; Ru, T.; Zhou, H. Surgical Outcomes of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: An 8-Year Experience at a Single Institution. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Zizolfi, B.; Saccone, G.; Ferrara, C.; Sglavo, G.; De Angelis, M.C.; Mastantuoni, E.; Bifulco, G. Hysteroscopic Resection vs Ultrasound-Guided Dilation and Evacuation for Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 229, 437.e1–437.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, X.; Shan, S.; Zhao, X.; Shi, B. Dilatation and Curettage Versus Lesion Resection in the Treatment of Cesarean-Scar-Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 60, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Pang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Cheng, L.; Ban, Y.; Cui, B. A Comparison Between Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy Approach in Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Medicine 2020, 99, e22845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cao, L.; Yan, J.; Tang, Y.; Cao, N.; Huang, L. Risk Factors Associated with the Failure of Initial Treatment for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 62, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lu, X.; Qu, W.; Hao, Y.; Mao, Z.; Li, S.; Tao, G.; et al. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy Clinical Classification System With Recommended Surgical Strategy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with Expectant Management. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calì, G.; Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Palacios-Jaraquemada, J.; Monteagudo, A.; Buca, D.; Forlani, F.; Familiari, A.; Scambia, G.; Acharya, G.; D’Antonio, F. Outcome of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Managed Expectantly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 36 | 29 |

| Gestation | 3 | 3 |

| Parity | 1 | 2 |

| Previous cesarean sections | 1 | 2 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 8 | 6 |

| Previous medical or surgical pathology | no | no |

| β-hCG level | - | - |

| Symptoms | vaginal bleeding | lower abdominal pain |

| Medical treatment prior to surgical treatment | systemic mifepristone | systemic methotrexate |

| Effective suction curettage | no | no |

| Author | Number of Patients | Gestational Age, Median, Weeks | Symptoms | MTX | Suction Curettage | Hysteroscopic Removal | Laparoscopic Removal | Expectant Management | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cagli et al. [17] | 56 | 7 | local MTX (all patients) | normalization of β-hCG was in 55.2 ± 41.0 days | |||||

| Casadio et al. [19] | 1 | 9 | Lower abdominal pain | local MTX | Hysteroscopic removal 6 weeks after MTX | effective | |||

| Xu et al. [21] | 117 | 33 patients (21 with type 1 CSP) | 84 patients (54 with type 2 CSP) | Both are effective | |||||

| Di Spiezio et al. [22] | 54 | <8 weeks and 6 days | Systemic MTX (all patients) | 27 patients | 27 patients | Hysteroscopic removal superior to suction curettage | |||

| Zhang et al. [24] | 112 | 7 weeks and 5 days | 72 patients | 42 patients | Both are effective | ||||

| Fu et al. [27] | 21 | All patients | Low myometrial thickness associated with serious complications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mihai, M.; Marius, G.C.; Vladut, S.; Claudiu, M. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Case Report in a Grade 2 Maternity and Review of the Literature. Reports 2025, 8, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040267

Mihai M, Marius GC, Vladut S, Claudiu M. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Case Report in a Grade 2 Maternity and Review of the Literature. Reports. 2025; 8(4):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040267

Chicago/Turabian StyleMihai, Muntean, Gliga Cosma Marius, Sasaran Vladut, and Mărginean Claudiu. 2025. "Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Case Report in a Grade 2 Maternity and Review of the Literature" Reports 8, no. 4: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040267

APA StyleMihai, M., Marius, G. C., Vladut, S., & Claudiu, M. (2025). Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Case Report in a Grade 2 Maternity and Review of the Literature. Reports, 8(4), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040267