Gastric Sarcina ventriculi: A Report on Two Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

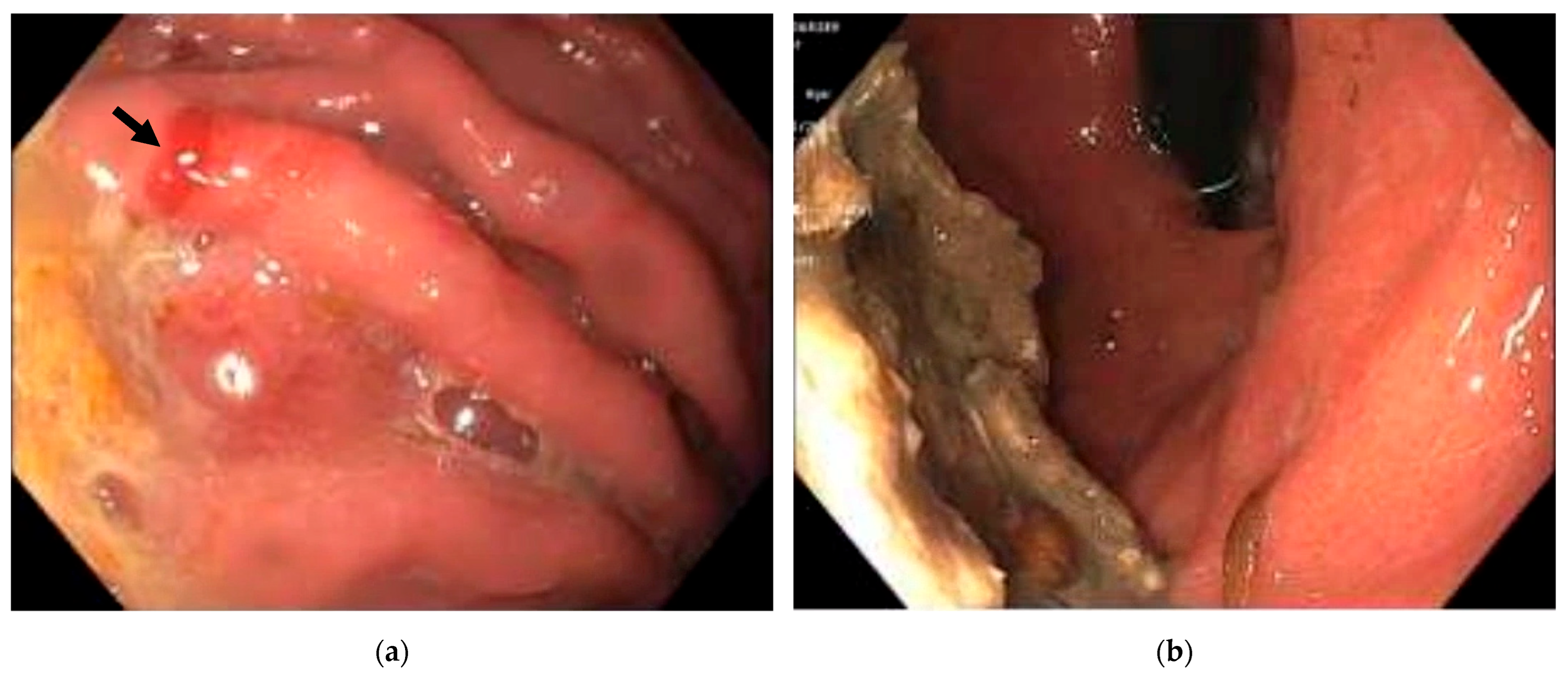

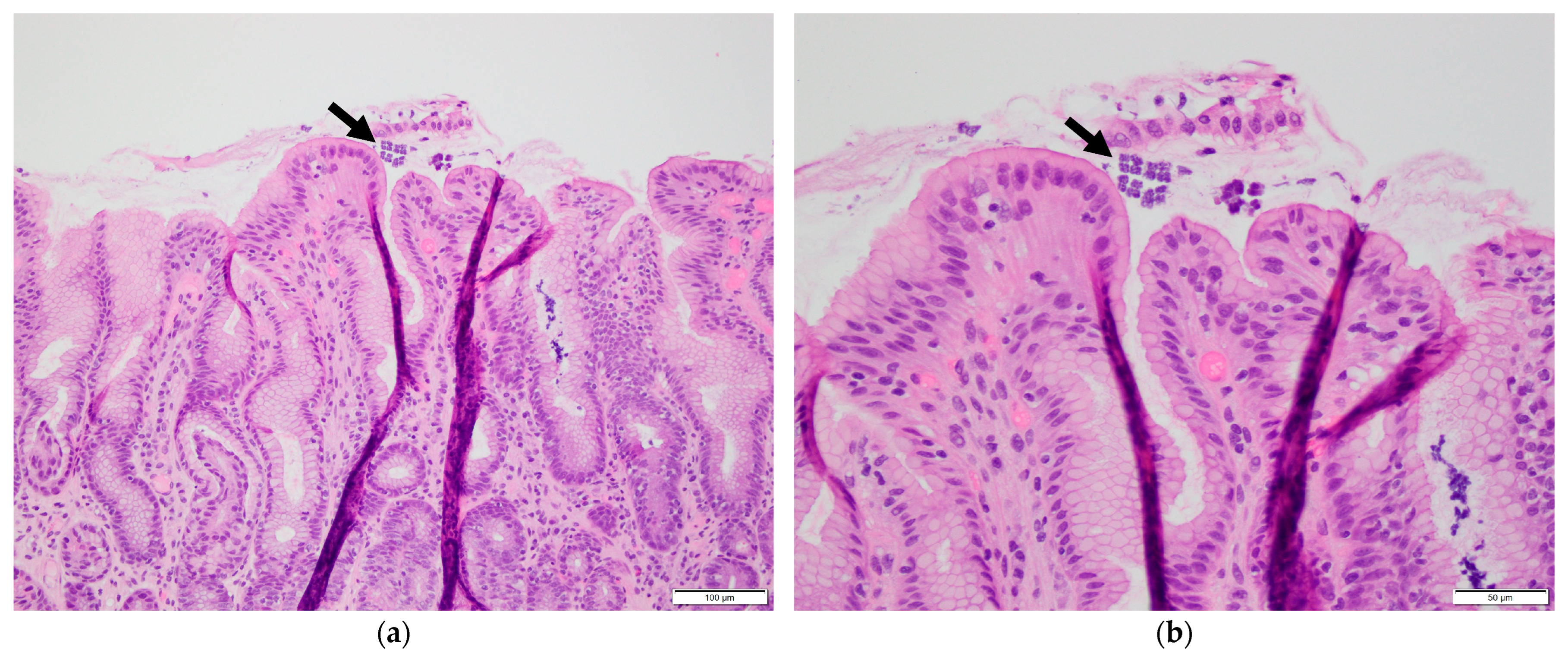

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canale-Parola, E. Biology of the sugar-fermenting Sarcinae. Bacteriol. Rev. 1970, 34, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.E.; Pankratz, H.S.; Zeikus, J.G. Influence of pH extremes on sporulation and ultrastructure of Sarcina ventriculi. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 3775–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ene, A.; McCoy, M.H.; Qasem, S. Sarcina organism of the stomach: Report of a case. Hum. Pathol. 2021, 25, 200541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintara, S.; Rice, S.; Patel, D. Sarcina organisms: A potential cause of emphysematous gastritis in a patient with gastroparesis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defilippo, C.; DeJesus, J.E.; Gosnell, J.M.; Qiu, S.; Humphrey, L. A rare case of erosive esophagitis due to Sarcina ventriculi infection. Cureus 2023, 15, e34230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Weber, M.A.; Low, J.; Krishnan, U. Sarcina in an adolescent with repaired esophageal atresia: A pathogen or a benign commensal? J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 69, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon Al Rasheed, M.R.; Kim, G.J.; Senseng, C. A rare case of Sarcina ventriculi of the stomach in an asymptomatic patient. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 24, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodsir, J.; Wilson, G. History of a case in which a fluid periodically ejected from the stomach contained vegetable organisms of an undescribed form. Edinb. Med. Surg. J. 1842, 57, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beijerinck, M. An experiment with Sarcina ventriculi. Huygens Inst. R. Neth. Acad. Arts. Sci. Proc. 1911, 13, 1237–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Xiang, D. Gastric bezoars secondary to mixed infection with Sarcina ventriculi and G + bacilli: A case report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propst, R.; Denham, L.; Deisch, J.K.; Kalra, T.; Zaheer, S.; Silva, K.; Magaki, S. Sarcina Organisms in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A report of 3 cases with varying presentations. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 28, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić Vuković, A.; Jonjić, N.; Bosak Veršić, A.; Kovač, D.; Radman, M. Fatal outcome of emphysematous gastritis due to Sarcina ventriculi infection. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2021, 15, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. Emphysematous gastritis associated with Sarcina ventriculi. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2019, 13, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, L.P.; Valentini, D.F.; Machado, S.M.D.S.; Schaefer, P.G.; Rivero, R.C.; Osvaldt, A.B. Sarcina ventriculi a rare pathogen. Autops. Case Rep. 2021, 11, e2021337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, B.; Salomao, D.R.; Boire, N.A.; Schuetz, A.N.; Sturgis, C.D. Sarcina ventriculi in an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of a perigastric lymph node with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A carry-through contaminant bacterial microorganism from the stomach. Case Rep. Pathol. 2021, 2021, 4933279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter, J.L.; Nayar, S.K.; Anders, P.D.; D’Amico, M.; Butnor, K.J.; Wilcox, R.L. Co-existence of Sarcina organisms and Helicobacter pylori gastritis/duodenitis in pediatric siblings. J. Clin. Anat. Pathol. 2013, 1, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, S.Y.; Kubik, M.J.; Savides, T.J.; Hasteh, F.; Hosseini, M. A rare case of Sarcina ventriculi diagnosed on fine-needle aspiration. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2019, 47, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sopha, S.C.; Manejwala, A.; Boutros, C.N. Sarcina, a new threat in the bariatric era. Hum. Pathol. 2015, 46, 1405–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Aliuş, C.; Nica, A.E.; Antoniac, I.; Gheorghița, D.; Gradinaru, S. Fatal outcome of gastric perforation due to infection with Sarcina spp. A case report. IDCases 2020, 19, e00711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotti, P.; Kipnis, E.; Faure, E.; Wacrenier, A.; Fauquembergue, M.; Penven, M.; Messaadi, S.; Marceau, L.; Dessein, R.; Le Guern, R. Clostridium ventriculi bacteremia following acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A case report. Anaerobe 2019, 59, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rasheed, M.R.; Senseng, C.G. Sarcina ventriculi: Review of the literature. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 1441–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attri, N.; Pareek, R.; Dhanetwal, M.; Khan, F.M.; Patel, S. Sarcina ventriculi associated gastritis: Mimicking lymphoma on endoscopy. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2023, 66, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, D.; Coccolini, F.; Mazzoni, A.; Strambi, S.; Cicuttin, E.; Cremonini, C.; Taddei, G.; Puglisi, A.G.; Ugolini, C.; Di Stefano, I.; et al. Sarcina ventriculi infection: A rare but fearsome event. A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 115, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaroff, R.; Goldberg, E.; Papadimitriou, J.C.; Twaddell, W.S.; Daly, B.; Drachenberg, C.B. Emphysematous gastritis due to Sarcina ventriculi infection in a diabetic liver-kidney transplant recipient. Autops. Case. Rep. 2020, 10, e2020164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Meij, T.G.J.; van Wijk, M.P.; Mookhoek, A.; Budding, A.E. Ulcerative gastritis and esophagitis in two children with Sarcina ventriculi infection. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuminen, T.; Suomala, P.; Vuorinen, S. Sarcina ventriculi in blood: The first documented report since 1872. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovska, M.; Modrackova, N.; Bolechova, P.; Drnkova, B.; Neuzil-Bunesova, V. Antibiotic susceptibility screening of primate-associated Clostridium ventriculi. Anaerobe 2021, 69, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkholz, T.; Kim, G.J.; Niehaus, H.; Conrad-Schnetz, K. Non-operative management of Sarcina ventriculi-associated severe emphysematous gastritis: A case report. Cureus 2022, 14, e31543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillman, L.; Jeans, P.; Whiting, P. Gastrointestinal: Sarcina ventriculi complicating gastric stasis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidinger, M.; Gorkiewicz, G.; Freisinger, O.; Brcic, I. Ulcerative reflux esophagitis associated with Clostridium ventriculi following hiatoplasty—is antibiotic treatment necessary? A case report. Z. Gastroenterol. 2021, 58, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Z. Gastric Sarcina ventriculi: A Report on Two Cases. Reports 2025, 8, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030128

Chen Y, Liu Y, Fu Z. Gastric Sarcina ventriculi: A Report on Two Cases. Reports. 2025; 8(3):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030128

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yaomin, Yu Liu, and Zhiyan Fu. 2025. "Gastric Sarcina ventriculi: A Report on Two Cases" Reports 8, no. 3: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030128

APA StyleChen, Y., Liu, Y., & Fu, Z. (2025). Gastric Sarcina ventriculi: A Report on Two Cases. Reports, 8(3), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030128