Extremely Rare Case of a Giant Paratubal Cyst, Coexisting with a Mucinous Cystadenoma, Surgically Treated Through Laparoscopy—A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kiseli, M.; Caglar, G.S.; Cengiz, S.D.; Karadag, D.; Yılmaz, M.B. Clinical diagnosis and complications of paratubal cysts: Review of the literature and report of uncommon presentations. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 285, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Stenbäck, F.; Kauppila, A. Development and classification of parovarian cysts. An ultrastructural study. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1981, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T.; Kozuma, S.; Kikuchi, A.; Hanada, N.; Sakamaki, K.; Yasugi, T.; Yamada, M.; Taketani, Y. Parovarian cystadenoma: Sonographic features associated with magnetic resonance and histopathologic findings. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2004, 32, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Muolokwu, E.; Sanchez, J.; Bercaw, J.L.; Sangi-Haghpeykar, H.; Banszek, T.; Brandt, M.L.; Dietrich, J.E. The incidence and surgical management of paratubal cysts in a pediatric and adolescent population. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 2161–2163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barloon, T.J.; Brown, B.P.; Abu-Yousef, M.M.; Warnock, N.G. Paraovarian and paratubal cysts: Preoperative diagnosis using transabdominal and transvaginal sonography. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1996, 24, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stein, A.L.; Koonings, P.P.; Schlaerth, J.B.; Grimes, D.A.; d’Ablaing, G., 3rd. Relative Frequency of Malignant Paraovarian Tumors: Should Paraovarian Tumors be Aspirated? Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 75, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Aslani, M.; Ahn, G.; Scully, R. Serous papillary cystadenoma of borderline malignancy of broad ligament. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1988, 7, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, L.G.; Holt, C.N.; Suarez, A.; Richardson, D.L.; Carlson, M.J.; O’Malley, D.M. Paratubal borderline serous tumors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 113, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, A.N. Kurman, R., Carcangiu, M., Herrington, C., Young, R.H., Eds.; Paratubal cysts. Female Genital Tumours. In WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Magistrado, L.; Dorland, J.; Sangi-Haghpeykar, H.; Patil, N.; Dietrich, J.E. Paratubal Cyst Recurrence in Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 33, 649–651. [Google Scholar]

- Almahmeed, E.; Alshaibani, A.; Alhamad, H.; Abualsel, A. Giant Paratubal Cyst Mimicking Mesenteric Cyst. Case Rep. Surg. 2022, 2022, 4909614. [Google Scholar]

- Tjokroprawiro, B.A. Huge Paratubal Cyst: A Case Report and a Literature Review. Clin. Med. Insights Case Rep. 2021, 14, 11795476211037549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asare, E.A.; Greenberg, S.; Szabo, S.; Sato, T.T. Giant paratubal cyst in adolescence: Case report, modified minimal access surgical technique, and literature review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015, 28, e143–e145. [Google Scholar]

- Alpendre, F.; Pedrosa, I.; Silva, R.; Batista, S.; Tapadinhas, P. Giant paratubal cyst presenting as adnexal torsion: A case report. Case Rep. Womens Health 2020, 19, e00222. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Farès, M.; Anis, K.; Anis, B.D.; Nada, E.; Bochra, R.; Yasser, K.; Mounir, B.M. Abdominal mass revealing a giant paratubal cyst. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1395–1396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ludovisi, M.; Foo, X.; Mainenti, S.; Testa, A.C.; Arora, R.; Jurkovic, D. Ultrasound diagnosis of serous surface papillary borderline ovarian tumor: A case series with a review of the literature. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2015, 43, 573–577. [Google Scholar]

- Moro, F.; Poma, C.B.; Zannoni, G.F.; Urbinati, A.V.; Pasciuto, T.; Ludovisi, M.; Moruzzi, M.C.; Carinelli, S.; Franchi, D.; Scambia, G.; et al. Imaging in gynecological disease (12): Clinical and ultrasound features of invasive and non-invasive malignant serous ovarian tumors. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 788–799. [Google Scholar]

- Butureanu, T.; Socolov, D.; Matasariu, D.R.; Ursache, A.; Apetrei, A.-M.; Dumitrascu, I.; Vasilache, I.; Rudisteanu, D.; Boiculese, V.L.; Lozneanu, L. Ovarian Masses-Applicable IOTA ADNEX Model versus Morphological Findings for Accurate Diagnosis and Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10789. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, M.A.; Vancraeynest, L.; Timmerman, S.; Ceusters, J.; Ledger, A.; Graupera, B.; Rodriguez, I.; Valero, B.; Landolfo, C.; Testa, A.C.; et al. Validation of ADNEX and IOTA two-step strategy and estimation of risk of complications during follow-up of adnexal masses in low-risk population. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 64, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, P.; Manaktala, U.; Khurana, N. Clinical, radiological, and histopathological analysis of paraovarian cysts. J. Midlife Health 2016, 7, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, K.; Ito, K.; Awaya, H.; Matsunaga, N.; Outwater, E.K.; Siegelman, E.S. Paraovarian cyst: MR imaging features. Abdom. Imaging 2002, 27, 685–689. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, J.E.; Adeyemi, O.; Hakim, J.; Santos, X.; Bercaw-Pratt, J.L.; Bournat, J.C.; Chen, C.H.; Jorgez, C.J. Paratubal Cyst Size Correlates with Obesity and Dysregulation of the Wnt Signaling Pathway. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Low, S.; Ong, C.; Lam, S.; Beh, S. Paratubal cyst complicated by tubo-ovarian torsion: Computed tomography features. Australas. Radiol. 2005, 49, 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, J.E.; Heard, M.J.; Edwards, C. Uteroovarian ligament torsion of the due to a paratubal cyst. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2005, 18, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Genadry, R.; Parmley, T.; Woodrdruff, J.D. The origin and clinical behavior of the paraovarian tumor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1977, 129, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Matsuo, K.; Mhawech-Fauceglia, P. Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma Arising in a Paratubal Cyst: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2017, 25, e21–e24. [Google Scholar]

| Imaging Modality | Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonography (US) | Location | Adjacent to the ovary and fallopian tube; may mimic an ovarian cyst. |

| Shape and Margins | Round or oval; thin-walled; well-defined. | |

| Internal Content | Anechoic (clear fluid); no internal echoes unless complicated. | |

| Mobility | Mobile, separate from the ovary; probe pressure may help differentiate. | |

| Doppler Flow | No internal vascularity in simple cysts. | |

| MRI | Signal Characteristics (T1/T2) | T1: Hypointense; T2: Hyperintense, consistent with simple fluid. |

| Wall Characteristics | Thin-walled, non-enhancing; absence of solid components. | |

| Ovarian Differentiation | Normal ovary seen separately; cyst is extraovarian. | |

| Post-contrast Enhancement | No enhancement unless complicated (e.g., hemorrhagic cyst). | |

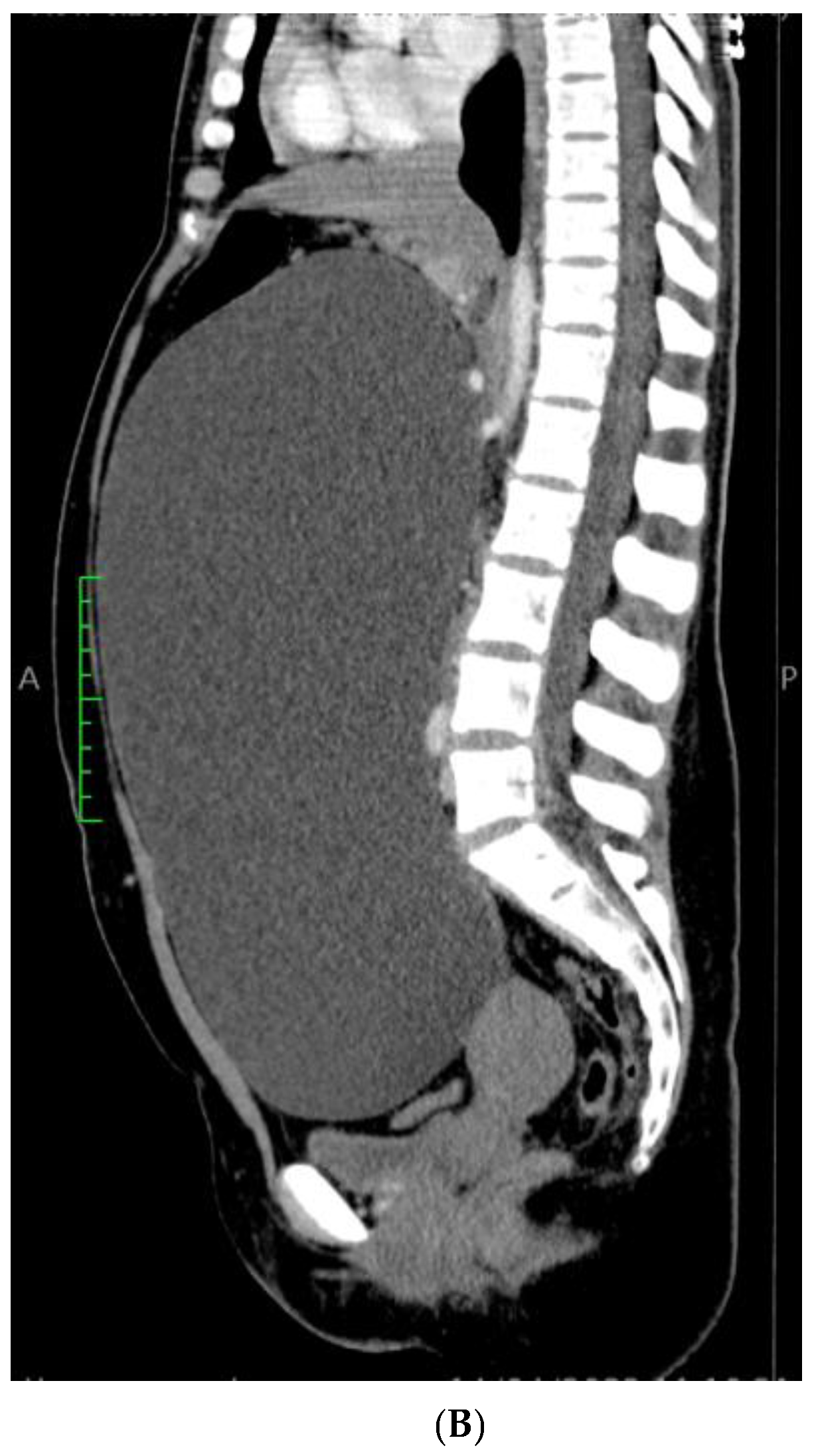

| Computed Tomography (CT) | Density | Hypodense, fluid-filled; attenuation similar to water. |

| Wall Appearance | Thin wall; no calcifications; well-circumscribed. | |

| Contrast Enhancement | No enhancement unless complicated or inflamed. | |

| Relation to Other Structures | Clearly separate from the ovary; usually near the fimbrial end of the fallopian tube. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Butureanu, T.A.; Apetrei, A.-M.; Pavaleanu, I.; Haliciu, A.-M.; Socolov, R.; Balan, R. Extremely Rare Case of a Giant Paratubal Cyst, Coexisting with a Mucinous Cystadenoma, Surgically Treated Through Laparoscopy—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Reports 2025, 8, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030106

Butureanu TA, Apetrei A-M, Pavaleanu I, Haliciu A-M, Socolov R, Balan R. Extremely Rare Case of a Giant Paratubal Cyst, Coexisting with a Mucinous Cystadenoma, Surgically Treated Through Laparoscopy—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Reports. 2025; 8(3):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030106

Chicago/Turabian StyleButureanu, Tudor Andrei, Ana-Maria Apetrei, Ioana Pavaleanu, Ana-Maria Haliciu, Razvan Socolov, and Raluca Balan. 2025. "Extremely Rare Case of a Giant Paratubal Cyst, Coexisting with a Mucinous Cystadenoma, Surgically Treated Through Laparoscopy—A Case Report and Review of the Literature" Reports 8, no. 3: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030106

APA StyleButureanu, T. A., Apetrei, A.-M., Pavaleanu, I., Haliciu, A.-M., Socolov, R., & Balan, R. (2025). Extremely Rare Case of a Giant Paratubal Cyst, Coexisting with a Mucinous Cystadenoma, Surgically Treated Through Laparoscopy—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Reports, 8(3), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030106