1. Introduction

Flexible Multibody dynamic Simulations (FMBSs) are a powerful tool for analyzing the behavior of complex machinery under real-world operational conditions, especially in the field of rotating machines where large rotational displacements are involved [

1]. The general framework was established several decades ago [

2] but is still the topic of recent works [

3]: each structural component is first modeled using the Finite Element Method (FEM), then reduced through Component Mode Synthesis (CMS) [

4], and then assembled using various types of connections (clamp, pivot, etc.) available in commercial software (ADAMS, SIMPACK, and SIMSCAPE).

In the context of turbomachinery architecture evolution and the growing availability of computational resources, coupled with the expensive nature of experiments, engineers are increasingly leaning towards high-fidelity virtual prototyping. While Flexible Multibody Software (FMBS) solvers exhibit commendable speed given the intricate nature of the models, the rising complexity of engine models leads to a substantial increase in computational burden. Indeed, the structures involve numerous components and connections featuring local damping or nonlinear stiffness. Furthermore, the behavior of these structures must be studied across a broad frequency spectrum. Consequently, the time integration for a single scenario can exceed ten hours, which is a deal-breaker in the design optimization phase.

Although the general framework for FMBS is now fairly standard, several significant scientific obstacles remain, particularly in the context of model reduction and CMS. Firstly, traditionally, CMS assumes linear behavior, but several contributors are seeking to incorporate nonlinearities into the behavior of these components: [

5,

6], for geometric nonlinearity; [

7], for material nonlinearity; or [

8], for friction nonlinearities. Secondly, there is great interest in CMS as it allows for parametric evolutions to be captured when dealing with materials that depend on frequency or temperature [

9] or when dealing with an optimization process or nonlinear simulation [

10]. Finally, research is focusing on linear CMS model improvement. An important way to optimize the reduced model is mode selection, as it reduces the number of variables. Recent approaches are mainly based on energy criteria [

11] or truncation error criteria [

12]. Recently, Janssen et al. [

13] proposed double criteria based on the frequency range of interest and the ability to capture the connection behavior. Our work focuses on this aspect and aims to compare several approaches dedicated to this objective. A key factor influencing computation time is the number of modes considered for modal superposition within each flexible body. Indeed, across all simulations conducted in

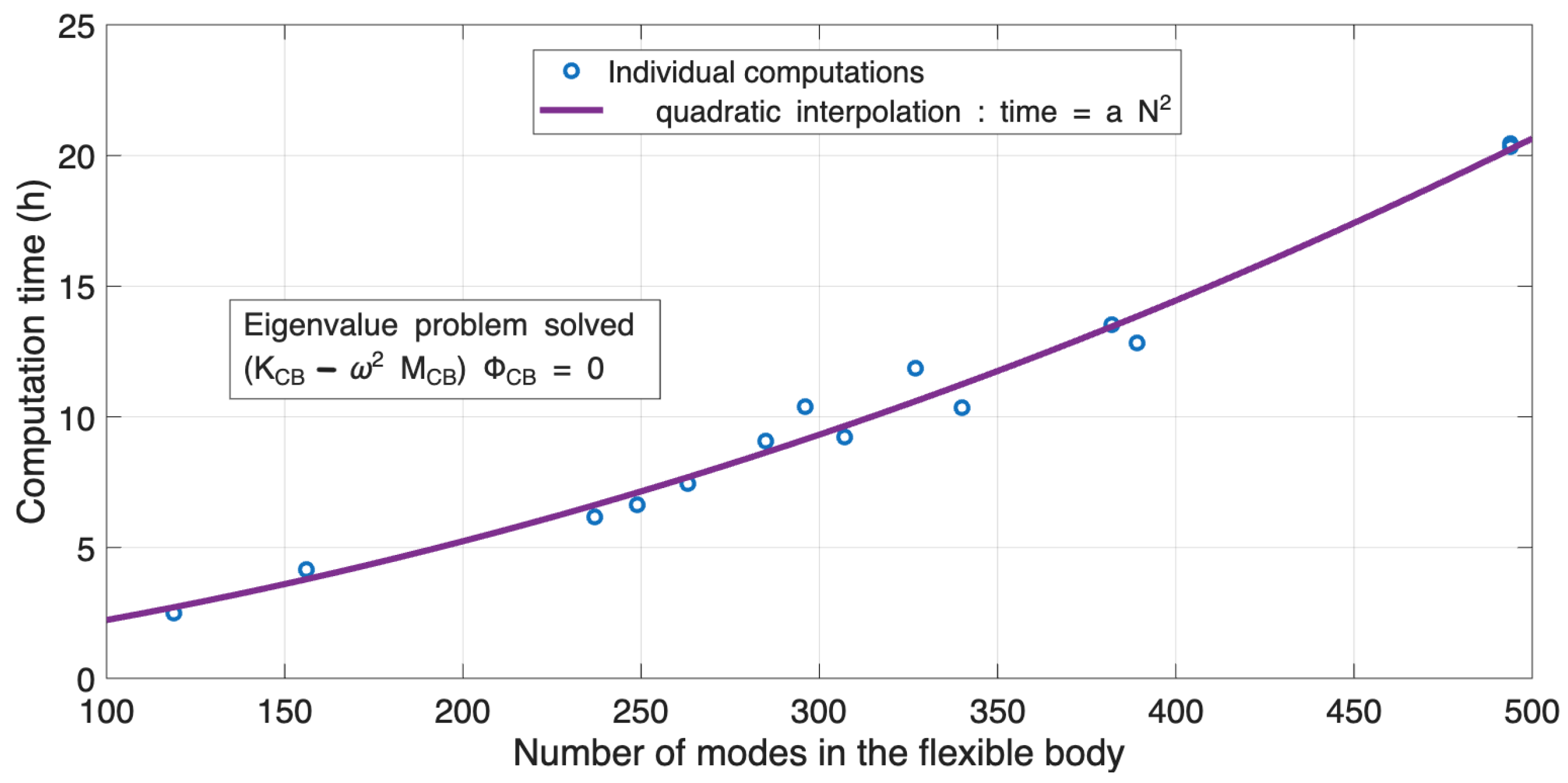

Section 3.3 using various modes in the modal basis, we observed a quadratic relationship between the number of modes and the time required for time integration.

Traditionally, a Craig–Bampton superelement [

4] for each flexible component is imported in FMBS software, consisting in mass and stiffness operators projected onto a basis comprising static modes (Guyan) and fixed-interface modes, also depicted as fixed-interface modes or constrained normal modes. Subsequently, a modal basis is internally recalculated based on the imposed boundary conditions in the model and truncated to the relevant maximal frequency of interest. Depending on the component’s geometry and material properties, a significant number of modes may be retained, but only a few actively contribute to the system’s response. Indeed, some of them may represent local mode shapes that are either not likely to be excited or contribute negligibly to the loads at the interface.

The local modes in the resulting Reduced-Order Model (ROM) arise from some particular internal Craig–Bampton dynamical modes preserved in the condensation. Various methods exist in the literature, aiming to filter them by means of participation factor computing. Notable methods include the following:

Effective Interface Mass (EIM) and its derivatives VEIM and DEIM proposed by Kammer in [

14];

Participation Factors introduced by Lenoir, Cogan, and Lallement [

15] (denoted LPF);

Optimal Mode Ranking (OMR) [

16];

, where CMS stands for Component Mode Synthesis [

17];

Interior Mode Ranking (IMR) [

18];

Energy-Based Ranking (EBR) [

11].

It can be noted that some of the filtering methods have been previously compared on simple academic test cases [

19,

20] highlighting IMR’s effectiveness and OMR’s poor performance. Additionally, EIM has been successfully applied to the crankshaft and the conrod of Multibody cranktrain model [

21]. In the present work, various ranking techniques are compared using an industrial case study: the stator of a next-generation aircraft engine.

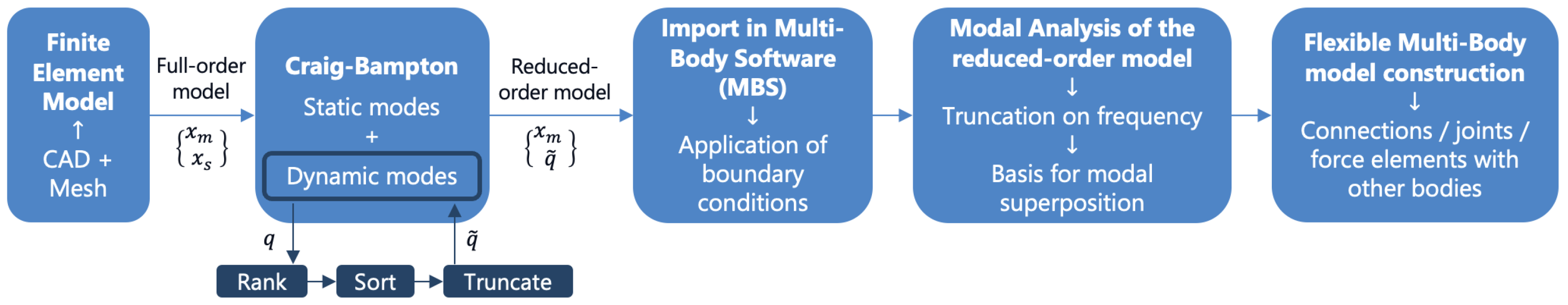

To bring it all together, the diagram in

Figure 1 outlines the general process of constructing an FMBS model, with a focus on the modified superelement generation. In this process, the fixed-interface modes of the Craig–Bampton superelements are ranked, sorted, and truncated to prioritize the most significant modes in the dynamic response of the structure rather than low-frequency modes. The nonlinear phenomena present in the gearbox do indeed induce high-frequency behavior related to harmonics. Nevertheless, all the methods compared, as well as the reference Craig–Bampton superelement, use the same frequency truncation rule: five times the maximum rotor speed for calculating the fixed interface modes used to construct the superelement and then two and a half times the maximum speed during modal analysis on the resulting superelement as part of the transient calculation. This choice of cutoff frequency is debatable, but it also comes with computational constraints. This study focuses on the frequency range described above, in line with industrial applications and needs.

In this paper, we aim to compare several of these methods on a realistic industrial case study, an aircraft engine model including a stator, two rotors, and a planetary gear train. The load case is an unbalance response. The evaluation criteria will focus on the computational time savings and the accuracy of forces and displacements at the bearings, which are also the interfaces of the superelements.

In this paper, we begin by recalling the basics of Craig–Bampton condensation and provide a concise overview of the different methodologies found in the literature to optimally select internal dynamical modes. They will be categorized into two groups: the a priori methods, which do not necessitate any prior knowledge of the crucial modes of the structure to be retained, and the a posteriori methods, which require prior knowledge of the important modes of the complete physical system to properly select the appropriate fixed-interface modes.

Subsequently, we assess a subset of these methods using an initial voluntary simplified industrial aircraft engine model, which involves a stator, two rotors, and a linearized planetary gear train. The evaluation aims to identify the most efficient approach based on criteria such as calculation time savings and the accuracy of load predictions across the entire structure.

Finally, we apply the most promising method to a nonlinear flexible multibody system featuring a comprehensive aircraft engine model. The assessment criteria remain centered on computational efficiency and the precision of load predictions throughout the structure.

2. Review of Craig–Bampton Mode Selection Techniques

The Craig–Bampton method (CB) stands out as one of the most extensively employed Component Mode Synthesis (CMS) techniques in structural dynamics. Introduced by Donald Craig and Clark Bampton [

4], it facilitates the design and the dynamic analysis of structure assemblies.

2.1. Theoretical Background

Each component is modeled individually, and the Craig–Bampton method provides a reduced-order model where the interfaces with other components retain physical degrees of freedom.

First, let us recall the conservative dynamic equation:

Here, M and K are matrices representing the mass and stiffness matrices, respectively; F is the vector of external forces; and U denotes the vector of degrees of freedom.

The

n degrees of freedom (DOFs) of the finite element structure are categorized into two groups: the “master” DOFs (designated with subscript

m) and the “slave” DOFs (subscript

s), such as

. Master nodes, also referred to as “boundary” nodes, are retained in the FMBS environment for applying forces, modeling connections, or positioning virtual sensors. Conversely, slave nodes, or “interior” nodes, are no longer in use. By reorganizing rows and columns of the finite element matrices, we can express Equation (

1) as follows:

R are the reaction forces resulting from a interface displacement field .

The next step involves computing static modes, commonly referred to as Guyan modes, denoted by

and determined by the following:

Then, considering all master nodes constrained, we compute the fixed-interface modes

, by solving the eigenvalue problem:

is the diagonal matrix of square eigenvalues. The set of fixed-interface modes

is reduced to a subset associated with natural frequencies lower than a cutoff frequency set by modeling assumptions, yielding

; such that the modal properties of the resulting superelement and the full-order model (FOM) in the frequency band of interest for the application remain close. The modal basis used for the coordinates transformation is represented by the matrix

T:

q represents the modal degrees of freedom. Finally, the projection of mass and stiffness operators into a reduced space yields the operators of the reduced order model:

2.2. A Priori Selection Methods

In this section, we will go through the a priori methods for ranking internal modes. Those techniques do not require any prior knowledge on the important modes of the structure.

On the one hand, the Effective Interface Mass (EIM) and Lenoir Participation Factors (LPFs) are fundamentally rooted in the concept of modal masses. The EIM method, however, distinguishes itself by additionally accounting for the influence of mass distribution at the interface.

On the other hand, the Optimal Mode Ranking (OMR) and CMS methods are grounded in the evaluation of strain energy within the structure. In essence, both approaches prioritize modes based on the amount of strain energy associated with each mode. Nevertheless, the primary discrepancy between them lies in the treatment of frequency in the ranking process.

For each method, we will express the modal participation factor denoted .

2.2.1. Lenoir Participation Factors (LPFs)

In 2002, D. Lenoir, S. Cogan and G. Lallement [

15] proposed to examine the relationship between the displacement at the interface

and the corresponding reaction forces

R to defines the excitability of the modes of the component with a clamped interface with respect to the inertial forces generated by the interface displacement. To do so, substituting Equation (

5) in Equation (

2) and premultiplying it by

yields the following:

where the eigenmodes of the component clamped at the interface satisfy the following orthonormality relations

and

, and where

In this method, the interface mass matrices

,

and

are neglected, resulting in

Then, we can obtain the relation between the reaction forces and the displacements at the interfaces:

where

is the

internal mode participation factor. This relation distinguishes the static component

and the dynamic component of the reduced interface mass matrix. The product

represents the classical modal effective mass matrix.

2.2.2. Effective Interface Mass (EIM)

Developed by Kammer and Triller in 1996, the Effective Interface Mass (EIM) factor determines the contribution of each constrained normal mode to the dynamic loads at the interface under general displacements of the interior. It is similar to the previous method but does not neglect the interface mass matrices.

The modal participation factor matrix is computed as follows [

14]:

The

row

contains the modal participation factors for the

fixed-interface mode. They represent multiplication factors for the acceleration inputs from the interface degrees of freedom numbered with the subscript

j. The larger the

entry in

, the more the

mode will be excited by the

input. Finally, the EIM factor for internal mode

i is obtained through the following equations:

The authors extended EIM to consider modal velocity VEIM (

13) and modal displacement outputs DEIM (

14), weighting low-frequency modes more heavily.

where

.

Instead of being ranked by increasing frequency as is the case in the classic Craig–Bampton framework, modes are ranked by decreasing EIM factor. The number of dynamic modes retained in the modal basis is determined by a mass-based criterion. The recommended approach is to retain at least 90 percent of the system’s mass. This involves keeping modes with higher EIM values until the cumulative sum reaches 0.9.

2.2.3. Optimal Mode Ranking (OMR)

Developed in 2004 by Givoli et al. [

16], the participation factor OMR for ranking the constrained normal modes, with eigenvalue

and eigenvector

, is obtained with the formula below:

This method had not been tested because it showed mitigated performances on academic cases compared to other methods, probably because not enough weight is given to the frequency of the internal modes as compared to other methods (see Equation (

17)).

2.2.4. CMS “khi”

Developed in 2007 by Liao et al. [

17] as a declination of OMR, the participation factor CMS

for ranking the constrained normal modes

is obtained with the formula below:

A relation between some participation factors is demonstrated in [

20] between Kammer’s methods, OMR, and CMS

:

where

is the frequency of

. It is shown that CMS

is equivalent to VEIM while being more computationally expensive. As a consequence, it will not be tested.

2.3. A Posteriori Selection Methods

In this section, we will go through the a posteriori methods for ranking internal modes. In contrast to a priori methods, they require prior knowledge of the important modes of the structure or excitation in order to choose the appropriate fixed-interface modes to keep for the condensation, ensuring good representability of the physical model by the superelement for the application case. But, ultimately, we want to perform the selection without initial calculations. For the a posteriori methods, we therefore opted for a definition of force that contains all possible components. This approach is clearly disadvantageous for a posteriori methods but corresponds to the reality of the intended use.

2.3.1. Energy-Based Ranking (EBR)

The mode selection criterion proposed in [

11] ranks the interior modes by using scalar coefficients representing the contribution of each interior mode to the mean kinetic and potential elastic energy stored by the complete system in a period of the external force. These coefficients provide a measure of the importance of each interior mode to the forced response of the full-order system and account explicitly for both the frequencies and the spatial distribution of the force.

The system is supposed to be excited on the master DOFs by a set of periodic external nodal forces

consisting of a sum of

harmonic components

:

where

is the

harmonic component of the periodic force and

,

, and

are respectively, the amplitude, the angular frequency, and the relative phase of the

harmonic component exciting the

DOF.

The contribution of the

interior mode to the system mean energy can be evaluated through the scalar coefficients:

with

and

arising from the partition of the contributions of

and

in

and with

, where

is the relative phase of the response of the

DOF to the

harmonic component and

represents the relative phase of the response of the

interior modal coordinate to the

harmonic component.

This method requires knowing the external force to be applied before generating the reduced-order model.

2.3.2. Interior Mode Ranking (IMR)

The mode selection criterion proposed in [

18], referred to as the Interior Mode Ranking (IMR) method, aims to rank the constrained normal modes according to the contribution they provide to the dynamics of one or more selected vibration modes of the full system with actual boundary conditions. The eigenvector matrix of the full system is denoted

V and has the size

.

The participation coefficients of the interior modes

i in the dynamics of the

normal mode of the full order system is as follows:

where

is the

fixed interface normal mode shape,

arises from the partitioning of the transformation matrix

into

(size

) and

(size

) that splits the contributions of both

and

, and the frequency of the fictitious force

is assumed equal to the angular frequency of the mode of interest

plus a small frequency shift and

is defined by the following:

where

and

arise from the partitioning on master and slave DOFs of the modal shape of the

mode of the full system.

This method requires knowing the modes of the full system that will be excited.

3. Improved Performances of Flexible Multibody Analysis

3.1. Presentation of the Industrial Application Cases

To reduce the duration of flexible multibody simulations, we have identified and reviewed several methods to improve the construction of the Craig–Bampton superelement. For comparative analysis, we will now apply these methods to a stator component v1 introduced into a deliberately simplified flexible multibody model featuring two rotors and a linearized planetary gearbox (Model A in

Figure 2). The Finite Element (FE) model of this particular stator component exhibits numerous local elastic modes, facilitating the distinction of the efficiency of various methods.

Subsequently, after identifying the most promising method, we apply it to another stator component v2, consisting of an improved version of stator v1, completed with a nacelle and a pylon. Stator v2 is integrated into a complete turbomachine model consisting of three rotors and a fully detailed nonlinear gear train (Model B in

Figure 2). The FE model of stator v2 is of better quality than v1 and exhibits less local elastic modes. Concerning the planetary gear train, each planet, the planet carrier, the sun gear, and the ring have flexible bodies. Detailed gear force elements are employed, accounting for the three-dimensional motion of components and meshing effects. Internal mode filtering is exclusively applied to the statoric parts because the rotors are modeled as beams, where all nodes are considered as master nodes, allowing no fixed-interface modes. Regarding the gear train, due to cyclic symmetry, we assume that there are no local deformations except for the teeth deflection, which we aim to preserve.

To classify the methods, the test case involves transient analysis of an unbalance response. A mass is attached to the low-pressure turbine, and the angular velocity of the rotors is linearly imposed from 0 to the maximum speed, while a resistive torque is applied in accordance with real-world operating conditions. The features under comparison include the evolution of loads in the bearings and suspensions of the engine with angular velocity.

3.2. Practical Implementation and Results

The full physical operators of the components are initially extracted as op4 files from the MSC Nastran (v2018) Finite Element model using a dedicated DMAP script. These files are processed using MATLAB (v2019b) routines to obtain them as MATLAB files. We then conduct a reordering of rows and columns to gather master nodes on the one hand and the slave nodes on the other hand. We also remove non-independent nodes from the model (attached with MPC—Multiple Point Constraint—or RBE—Rigid Body Element—for example).

Both stator versions have 13 master nodes, which means 78 master DOFs, resulting in the same amount of static modes, which are computed according to (

3). Constrained normal modes are computed, ranked, and sorted by decreasing participation factors for each method. Considering that the stator (v1 or v2) features over 150,000 degrees of freedom, and due to limited computational resources, the computation of all fixed-interface modes is hardly feasible. Consequently, our approach involves calculating these modes up to five times the maximum frequency of interest. Modes beyond this limit are unlikely to exhibit significant participation factors.

Finally, the ranked and sorted modes are truncated based on criteria defined in the literature or through trial and error to evaluate performance in the industrial application case. Full mass, stiffness, and damping operators are projected onto a modified Craig–Bampton basis, retaining the most significant modes according to each ranking method. The reduced-order matrices are written in a binary file for compatibility with the multibody software and imported into the whole-engine model.

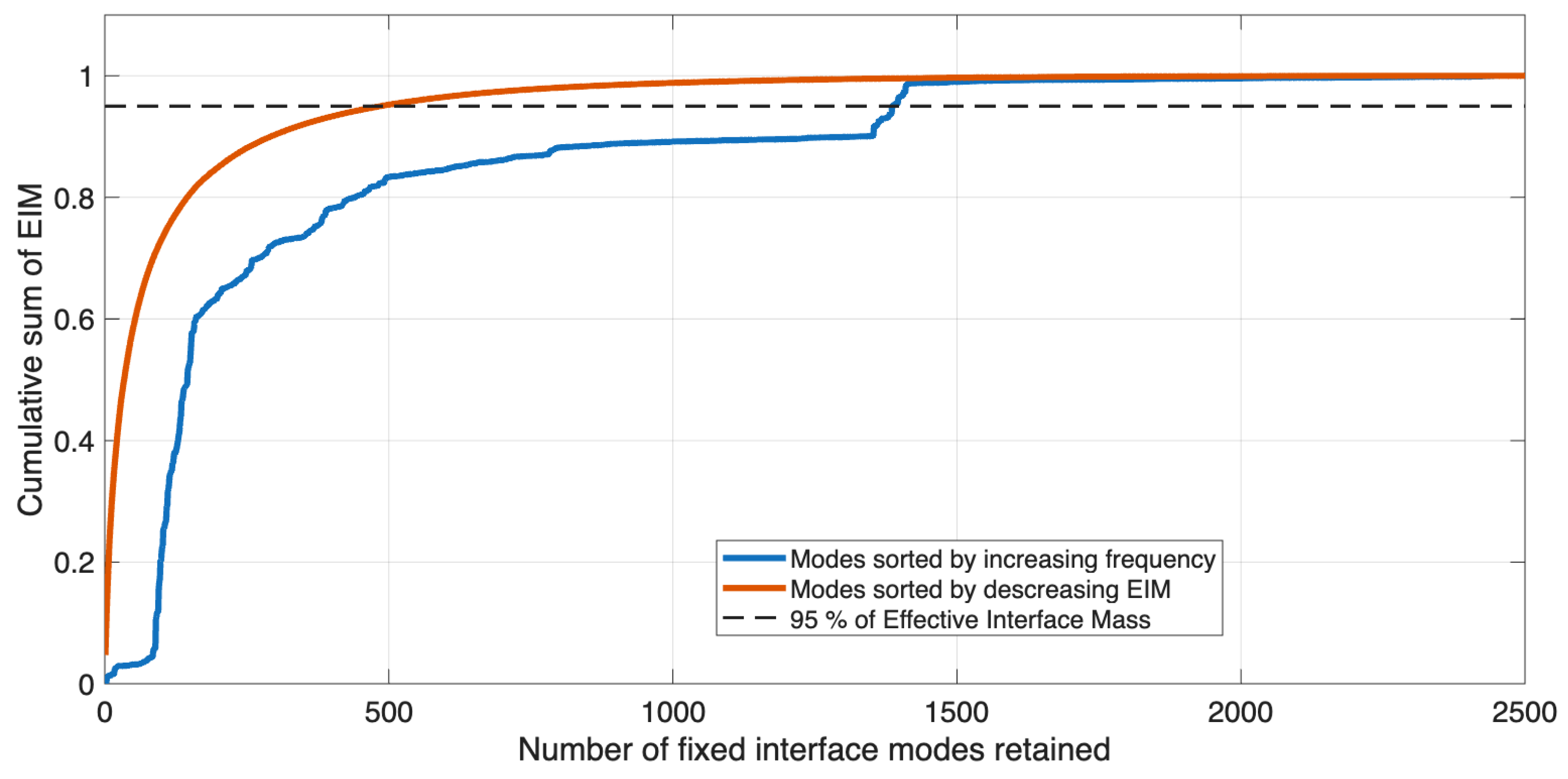

As an illustrative example, let us focus on the application of Effective Interface Mass (EIM).

Figure 3 compares the cumulative sum of EIM values for modes sorted by increasing frequency, as in the classic Craig–Bampton method, against modes sorted by decreasing EIM. This comparison reveals that many low-frequency modes in the structure exert minimal influence on the system’s response at interface and can be safely excluded from the projection modal basis.

Kammer and Triller recommend truncation to ensure a minimum of 90% effective interface mass. In a conservative approach, maintaining 95% of Effective Interface Mass (EIM) would necessitate selecting approximately 1400 modes when sorted by increasing frequency. However, when ordered by decreasing EIM participation factor, only 500 modes would be enough. In the latter case, the resulting superelements would have fewer modal DOFs, with the number of physical DOFs remaining the same.

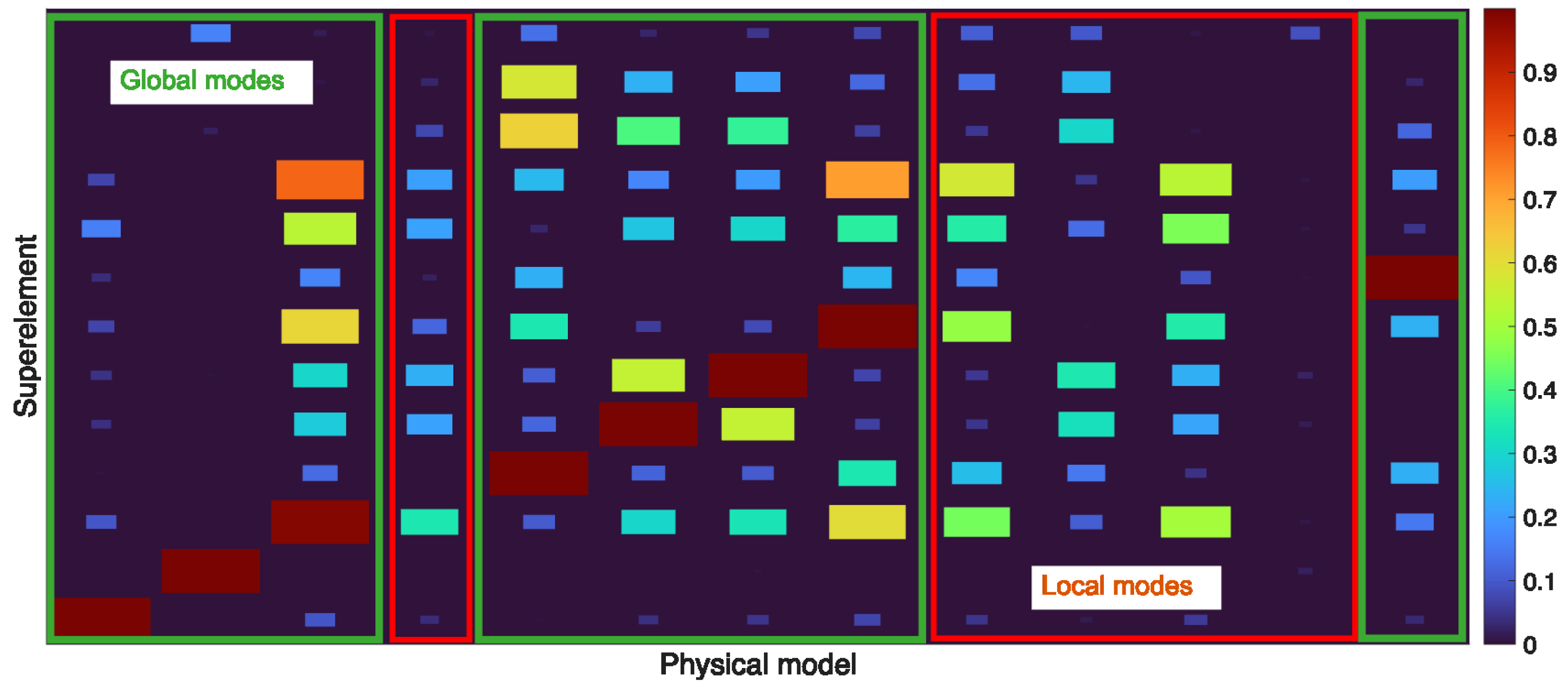

Figure 4 shows the Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC; see (

23)) matrix between the modes of the EIM superelement and the full physical model. To make the figure easier to read, the matrix is reduced to the first 13 modes. They are representative of the entire matrix. While the low-frequency modes of a classic Craig–Bampton superelement correspond to those of the full-order model and would show a diagonal with ones, here, certain modes (highlighted in red boxes) present in the FOM are absent in the EIM superelement. These modes correspond to local elastic modes, while global modes are well-represented (MAC > 0.95 attesting to the resemblance of modal shapes (green boxes)).

We have successfully reduced the number of modes of the superelement in the relevant frequency range from 494 to 340. This reduction significantly cuts down the computational time required for the multibody simulation, all while maintaining a very good accuracy of the results. The excluded modes, having negligible contributions to the system’s response, do not compromise the overall outcomes.

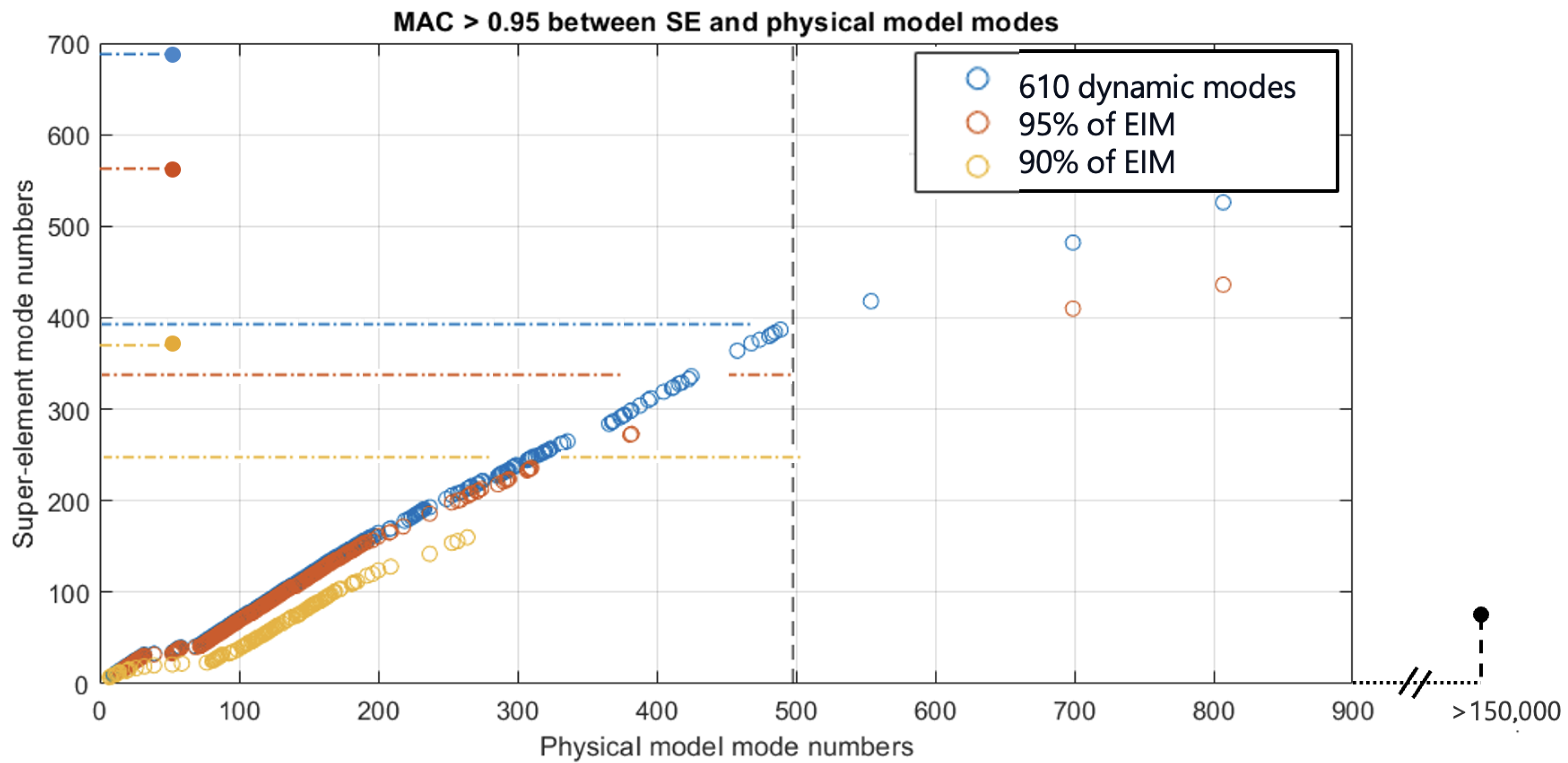

Furthermore, it is worth discussing the selection criteria for EIM. In

Figure 5, only MAC values greater than 0.95 are plotted, comparing the mode shapes of resulting EIM superelements with selection criteria 90%, 95% and 610 modes to those from the full Finite Element (FE) model modal analysis. The short dashed horizontal lines indicate the number of degrees of freedom of the substructure, while the long dashed horizontal lines represent the number of internal modes. The vertical line indicates the number of modes to be used in the physical model, for modal superposition in the frequency range of interest.

As expected, the less restrictive the selection criteria, the more internal modes are kept, the better the correspondence between the FOM and the ROM within the studied frequency band. However, this also leads to reduced potential for decreasing computation time. Therefore, the ultimate decision entails finding a balance between the desired prediction accuracy and the need for saving computation time.

3.3. Performance Benchmarking of Selection Techniques

For the purpose of comparison, a reference model was used to evaluate both computational time savings and the loss of precision in bearing load estimations. This reference model employed the Craig–Bampton method with a truncation frequency set to five times the maximum frequency of interest, resulting in 1650 dynamic modes within the superelements, in addition to the 78 static modes. This approach yielded a total of 494 modes considered after integration into the MBS model and truncation to the frequency of interest. The time integration for this reference model required approximately 20 h.

The process described in the previous subsection is replicated for most a priori methods, employing various truncation criteria. The a posteriori method IRM was omitted from testing, as it is deemed unsuitable for our case. To determine the appropriate modes from the full physical model, one would need to conduct an expensive simulation and invest effort in analyzing modal participations. Given the presence of several hundred modes, identifying the relevant ones becomes a challenging task. The other a posteriori method, referred to as EBR, was tested by selecting arbitrary excitation forces. This approach was necessitated by the lack of prior knowledge about the locations of loads without running the simulation. Consequently, we are not confident in the method’s relevance in this case, as the excitation forces are chosen without prior information.

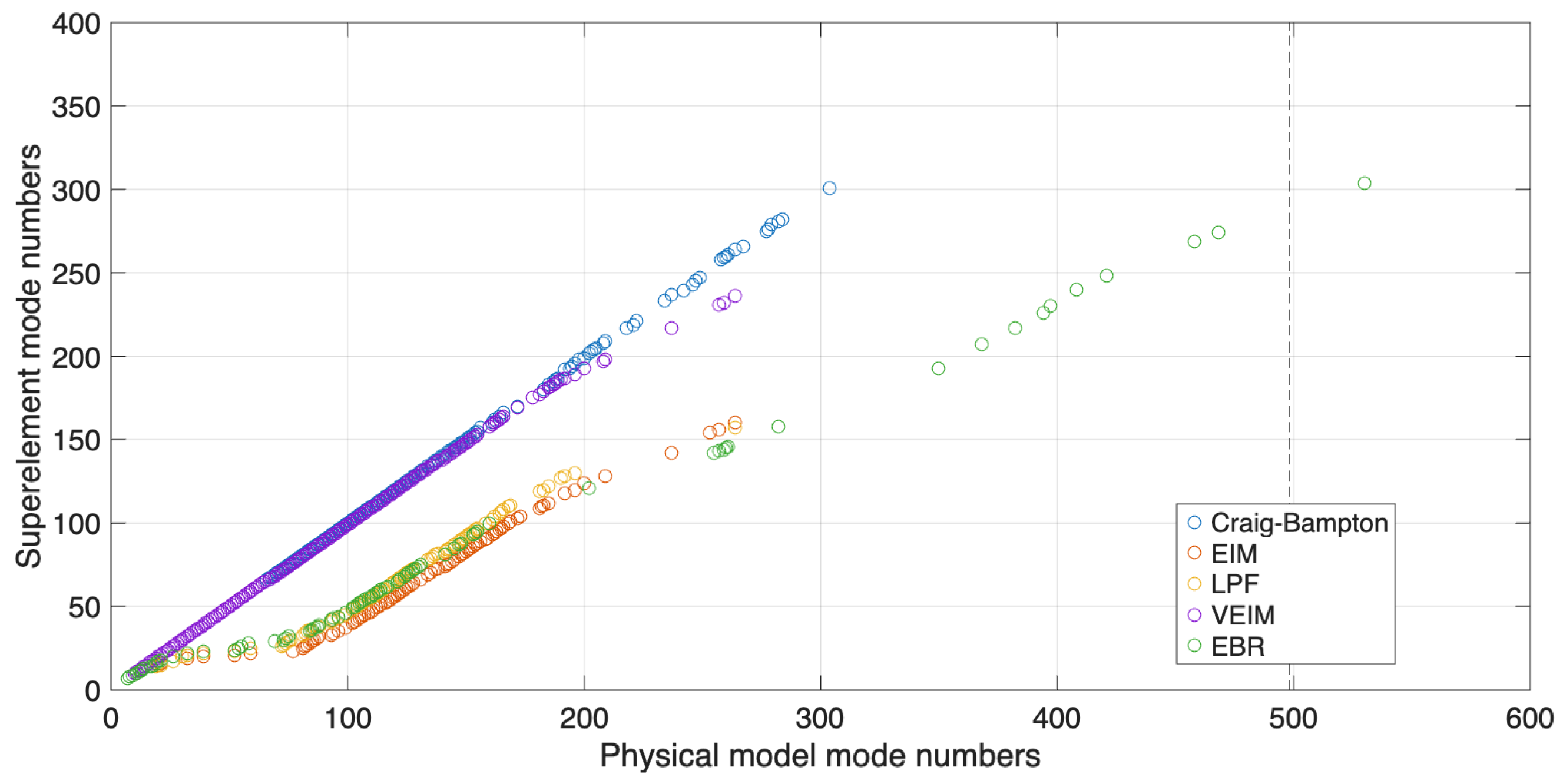

For each mode selection method and chosen selection criterion, the number of retained dynamic modes for condensation is specified in

Table 1, along with the difference between the resulting number of modes used for modal superposition in the multibody simulation and in the reference case. The differences between the methods rely in the choice of internal modes and its intricate link to the resulting number of modes in modal basis of the ROM. For instance, all methods were tested while retaining the first 292 internal modes sorted by decreasing participation factors. Notably, the number of resulting statoric modes used for time integration varies. These discrepancies can be further investigated in

Figure 6, where MAC > 0.98 are plotted between FOM and ROM for the various methods, highlighting their distinct selectivity tendencies. We can, for example, confirm the statement that VEIM assigns more significance to low-frequency modes than EIM. Another observation is that all methods filtering low-frequency modes seem to target approximately the same FOM modes for elimination.

The percentage of time saved compared to the reference model is also provided. The relation between time savings and the amount of statoric modes in the frequency range for analysis is highlighted in

Figure 7. Indeed, the calculation time depends linearly on the number of degrees of freedom

N for solving second-order differential systems, but the algebraic-differential equations associated with mechanical connections introduce a “complexity” that leads to solution times proportional to the cube of the number of degrees of freedom. Recent work [

22] shows that it is possible to reduce the time required to solve constraint equations without, however, achieving proportionality to

N. In our case, proportionality to

has been observed empirically.

Furthermore, we compute the maximum relative error

observed during the complete ramp-up phase using Equation (

24), where

x represents the observed value and

denotes the reference value:

Out of the eight load features, is given in the table for the worst load feature, as well as the best and mean out of the eight.

Finally, a score out of 20 is calculated based on the accuracy and time saving according to the following rules:

if , else,

0/10 if , else

The best marks are obtained for the EIM and LPF methods. The latter is applied in the next section on the statoric parts of the next generation of civil aircraft engines CFM RISE for industrial validation. The EIM method is indeed equivalent to the LPF method, which does not neglect the mass terms at the interface. The similar results obtained using these two methods show that the mass at the interface has little effect in the case of the stators studied. This conclusion can be generalized to any structure with distributed mass and relatively small interfaces.

3.4. Validation

The most promising methods for fixed-interface mode selection had been identified thanks to a benchmark based on the intentionally simplified yet relevant model A (cf.

Figure 2).

Lenoir’s method with selection criterion set to 95% of the mass is applied to model B, which represents the most detailed FMBS model of RISE to date, including notably the nonlinear effects of the planetary gear box. The gain in computational time was 17.6% (22.25 h instead of 27 h), which is particularly noteworthy considering the minimal additional effort required. Indeed, it only requires adding a single line of code to call a DMAP script implementing the LPF method to the Nastran file used for superelement construction. Moreover, it is worth noting that the performed improvement pertains to only a small portion of the DOFs of the entire system, exhibiting linear behavior. As for the accuracy of prediction, it was excellent for the application discrepancies inferior to 1%, observed on all the load features while performing unbalance response on the low-pressure turbine. The explanation lies in the fact that much of the high-frequency behavior is captured by static modes (Guyan). Since the nonlinearities are not internal to the superelement, the latter filters the excitations that reach it. Guyan modes ensure the transmission of forces from one bearing to another, regardless of the choice of frequency truncation. The results obtained on model B show, through their fidelity to the reference simulation, that there is no need to question the selection method when nonlinearity occurs outside the reduced model. Indeed, the dominant frequency content in the response (in terms of amplitude) is clearly present in the range.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Flexible Multibody Simulations are efficient for predicting loads in complex nonlinear structures in operation. However, despite the ongoing advancements in computational resources, FMBS can impose a substantial computational burden. Through our investigation, we have observed that the computational time required for temporal simulation of a simplified aircraft engine model exhibits a quadratic relationship with the number of retained modes of the stator’s flexible body for modal superposition. Consequently, reducing the number of superelement modes within the frequency range of interest is essential to reduce computational time, particularly when the structure contains local elastic modes that have minimal significance in the overall system response.

In this study, we have adapted the classical Craig–Bampton reduction methods by incorporating various existing techniques from the literature, which offer a refined selection of dynamic modes. To assess the efficiency of these methods, we conducted a comparative analysis based on results obtained from a speed ramp-up with unbalanced response in a realistic aircraft engine model. This evaluation primarily considered time-saving benefits and the accuracy of load predictions.

Our findings highlight two standout methods: the Effective Interface Mass method, as proposed by Kammer [

14], and a method proposed by Lenoir and Cogan in [

15]. These methods have demonstrated the ability to achieve significant computational time reductions, up to 65 percent, while introducing a maximal relative error of 4 percent in load predictions for all bearings during the ramp-up phase, which is satisfactory for the application.

In the scope of this work and with regard to the time available, the methods OMR and CMS have not been employed due to their recognized lower efficiency on academic test scenarios or similarities with other tested methods. Likewise, the exploration of the IMR method has been omitted due to its restricted relevance to the specific application as it necessitates prior knowledge of the modes to retain from the full-order system in order to select the most suitable fixed-interface modes for Craig–Bampton’s condensation.

The list of tested methods is not exhaustive and only concerns improvements of the Craig–Bampton reduction method, which is most widely used in commercial multibody software. Nevertheless, there are alternative approaches, such as moment-matching by projection on Krylov subspaces or SVD-based reduction techniques to take into account the time-varying boundary conditions in the reduction step [

23,

24,

25]. Those are worth including in this benchmark. However, due to considerations regarding integration feasibility with existing industrial methods, time constraints, and the already satisfactory results obtained, these methods were not explored as part of this study.

In the future, it is certainly the use of superelements constructed from data, so-called “surrogate models” [

26], that could make it possible to select fewer variables to simulate, further reduce calculation times, and improve accuracy.