3.1. Spatial and Territorial Characterisation of LFF

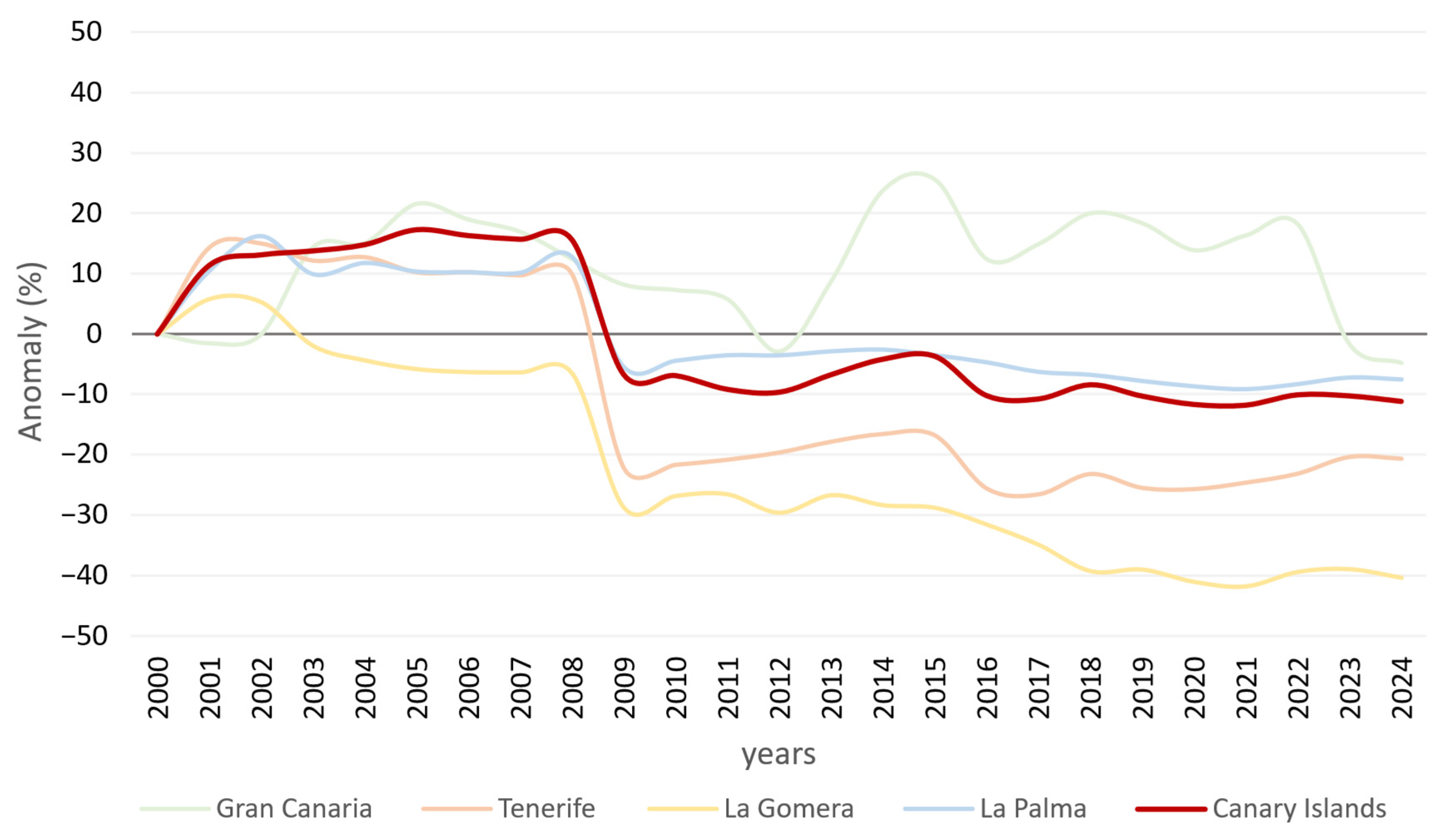

This subsection summarises the main spatial patterns of LFFs across islands, municipalities and elevation ranges. Over the past 14 years (2012–2024), a total of 13 forest fires have been recorded in the Canary Islands (

Figure 2). These occurred on Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma, and La Gomera—the islands of greatest elevation—where climatic conditions favour the development of dense and diverse vegetation, thus promoting the occurrence and spread of LFF. In contrast, Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, which are considerably more arid, lack the dense vegetative formations required to sustain fires of such magnitude.

During this period, a total of 55,167 hectares burned, representing 7.4% of the archipelago’s total land area. The recorded fires varied widely in size and duration (

Table 2). The largest event occurred in August 2023, burning 13,977 ha and affecting 13 municipalities. It was followed by the 2019 Gran Canaria fire, which burned 9783 ha. In contrast, the smallest event occurred in April 2018 on Tenerife, affecting a single municipality and burning 391.89 ha.

The comparison between the burned areas and the perimeters of the recorded fires (

Table 2) reveals considerable variability in the magnitude and shape of the events. The largest fire, both in area and perimeter, occurred on Tenerife in August 2023 (TF/8/23), affecting 13,977 hectares with a perimeter of 304.6 km. It was followed, in terms of burned area, by the 2019 Gran Canaria fire (GC/8/19), which affected 9321.1 ha with a perimeter of 126.7 km, and by the 2012 Tenerife fire (TF/7/12), which burned 6277.8 ha with a perimeter of 57.7 km. Conversely, the smallest fires occurred in April 2018 on Tenerife and July 2023 on Gran Canaria, burning 391 and 446 ha, respectively, with perimeters ranging between 15 and 16 km. These differences between burned area and perimeter illustrate the wide variability in fire size and shape among events

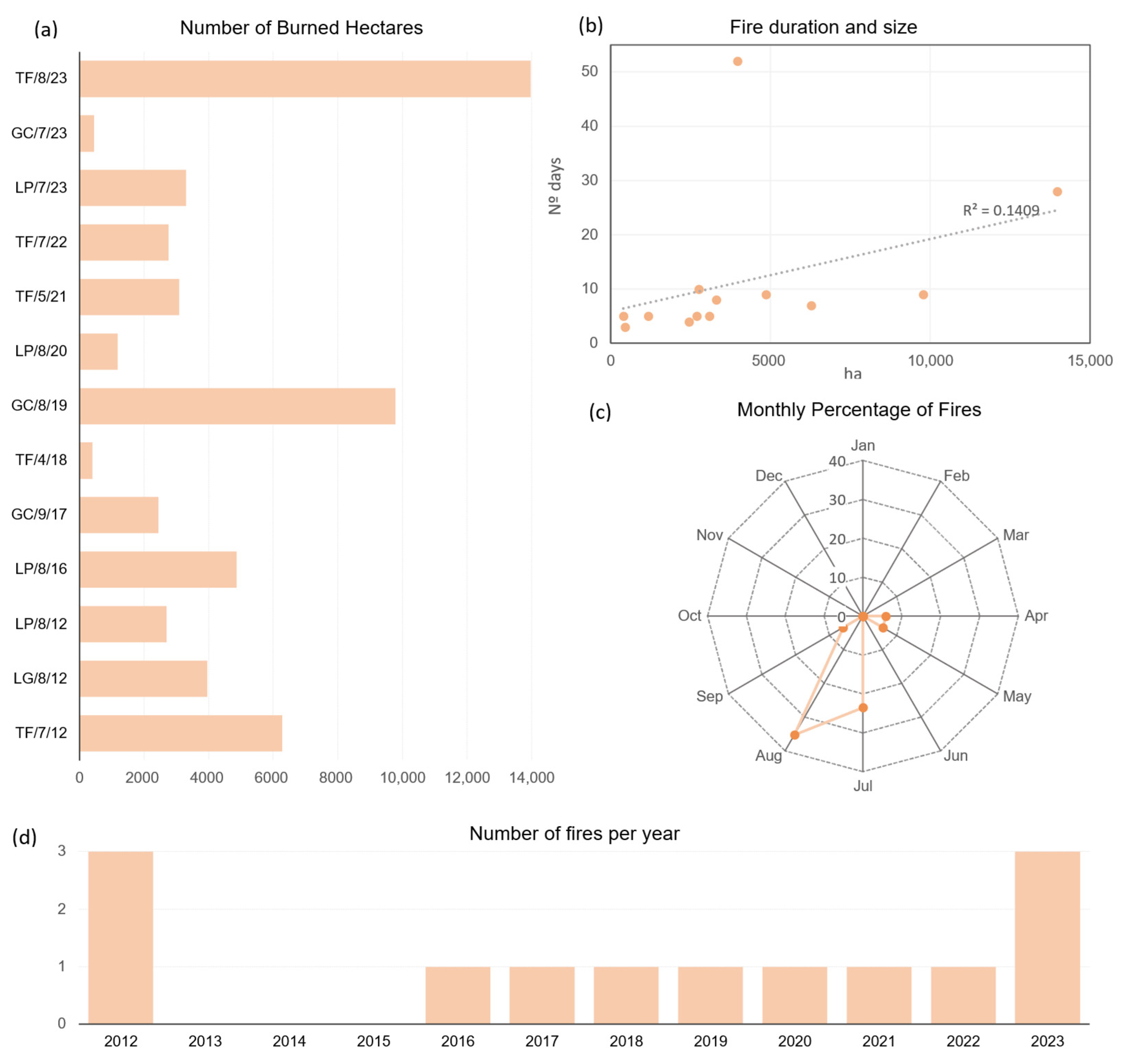

In terms of temporal distribution (

Figure 3c), August shows a high concentration of large-scale fires, due to climatic conditions favourable to fire spread. In this regard, 59% of these fires occurred between July and August, coinciding with the warmest period of the year in the archipelago, with four and six events, respectively. During these months, fires reached the largest average burned areas—3194 ha in July and 6077 ha in August. Together, these two months account for the majority of the total burned area, reaching 36,342.94 ha. Nevertheless, fires were also recorded outside the typical fire season, such as in April, May and September, although these do not correspond to the hottest periods in the archipelago. Only one fire was recorded in each of those months. The latest fire in the record occurred in September 2017, burning 2476 ha.

In terms of temporal duration (

Figure 3b), during the analysed period a total of 150 days were marked by the presence of uncontrolled or unstabilised Large Forest Fires (LFF). On average, each fire lasted 11.5 days, although substantial temporal variability was observed. The longest events corresponded to major fires such as the August 2012 fire on La Gomera, which persisted for 52 days and affected six municipalities, and the August 2023 fire on Tenerife, which lasted 28 days. In contrast, 46% of the fires lasted fewer than five days. The correlation between burned area and fire duration was low (R

2 = 0.14), indicating high variability in response capacity and containment effectiveness.

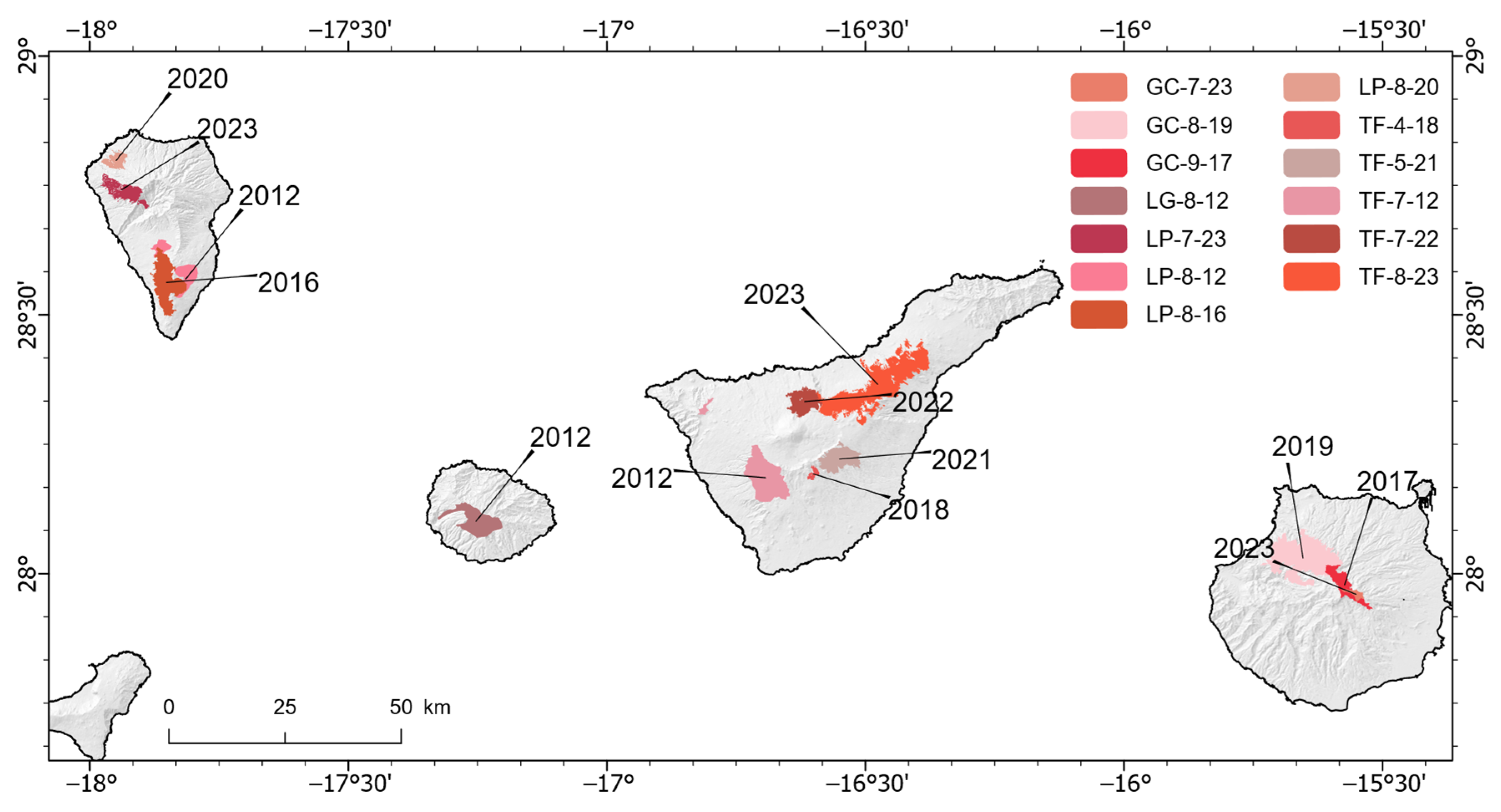

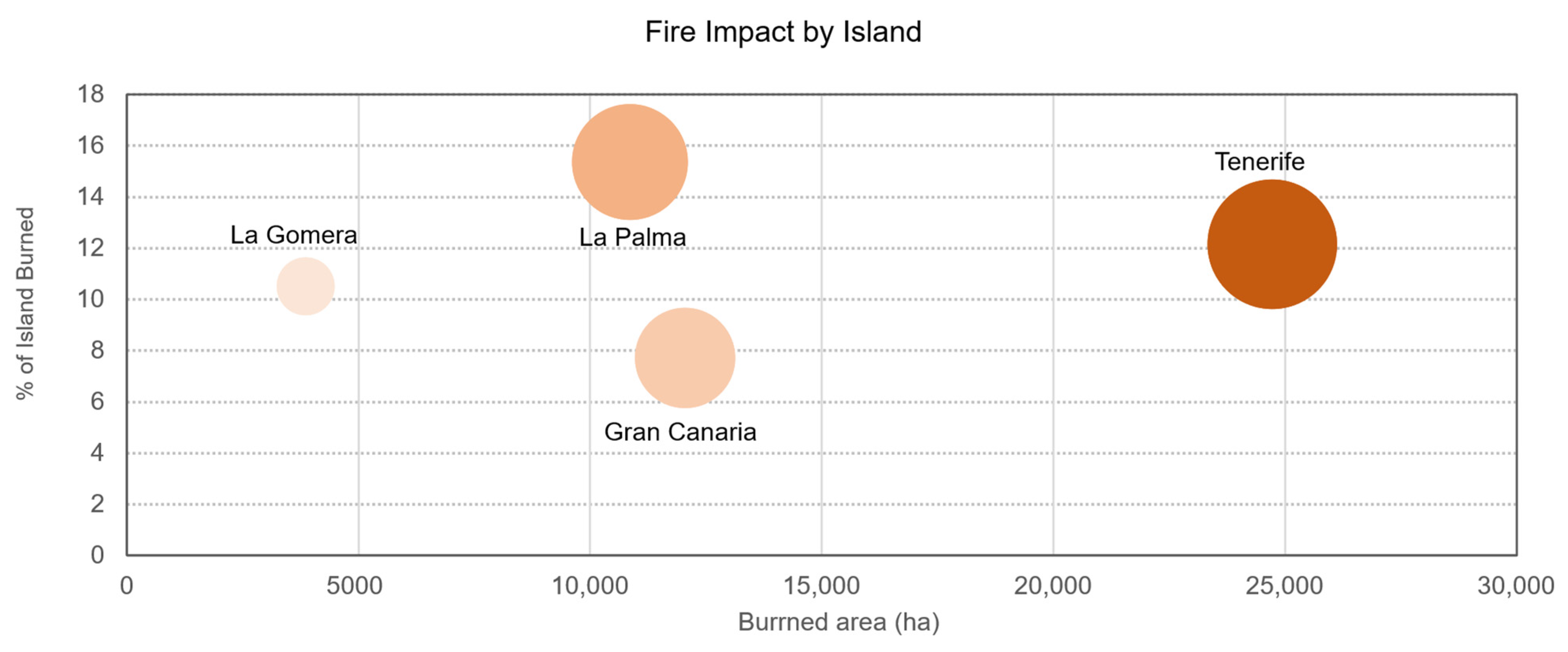

A more detailed analysis reveals that La Palma is the island most affected proportionally by forest fires (

Figure 4). Although the total burned area amounts to 10,859 ha—a figure lower than that of Tenerife—these areas represent 15.36% of the island’s territory, making it the most impacted in relative terms. In total, the island has recorded four fires. Tenerife follows, with 24,730 ha burned—the highest absolute value in the archipelago—equivalent to 12.16% of its surface area, across five fires. In Gran Canaria, the three recorded fires affected 12,053 ha, representing 7.72% of the island’s total area. Finally, La Gomera experienced a single fire that burned 3862 ha, equivalent to 10.51% of its territory.

Regarding the most significant events on each island, the 2019 fire in Gran Canaria and the 2023 fire in Tenerife stand out, each affecting around 6% of the respective island’s surface. In La Palma, the most severe event occurred in 2023, burning 2429 ha in just two days, equivalent to 3% of the island’s total area.

When the scale is reduced, it becomes evident that 51 of the 88 municipalities in the Canary Islands were affected—to varying degrees—by at least one forest fire during the study period (

Figure 5). The municipal-level analysis reveals significant differences in terms of total burned area, number of recorded fires and the average number of hectares affected per event. The mean burned area per municipality varies widely, ranging from very small values—less than 1 ha—to more than 3000 ha.

In terms of total burned area, the most affected municipalities were La Orotava (Tenerife), with 4373.6 ha; Artenara (Gran Canaria), with 3816.4 ha; El Paso (La Palma), with 3355.9 ha; Arico (Tenerife), with 3083.5 ha; and Villa de Mazo (La Palma), with 2639.2 ha. In contrast, the least affected municipalities were Breña Baja (La Palma), with barely 0.002 ha burned; Buenavista del Norte (Tenerife), with 3.14 ha; and Agulo (La Gomera), with 38.97 ha.

The number of recorded fires also varied notably between municipalities. Most of them (65%, 33 municipalities) were affected by a single fire. The highest values were observed in La Orotava (Tenerife), with four fires, followed by Tejeda (Gran Canaria), with six, and Los Realejos (Tenerife) and Vega de San Mateo (Gran Canaria), with four and seven fires, respectively. In other municipalities, such as Tijarafe (La Palma), Vallehermoso (La Gomera) and Artenara (Gran Canaria), only one fire was recorded during the analysed period.

In terms of the average burned area per fire, the highest values were found in Artenara (3816.4 ha per fire), Arico (3083.5 ha per fire) and Vallehermoso (1462.9 ha per fire). At the opposite end, the lowest averages corresponded to Breña Baja (0.002 ha per fire), Agulo (38.97 ha per fire) and Ingenio (11.25 ha per fire). These results confirm La Orotava as the most affected municipality by forest fires across the entire archipelago. Viewed across both islands and municipalities, LFFs show a consistent concentration in areas with extensive forest cover, mid-altitude belts and rural–forest mosaics.

The recorded ignition altitudes of the analysed fires range between 541 and 1970 m above sea level, with a clear concentration at intermediate elevations—particularly between 750 and 1500 m—where 67% of ignition points were located. The most frequent altitudinal range for fire ignition corresponds to 1000–1250 m, with three fires, representing approximately 23% of the total. Below 500 m, only one fire was recorded (La Gomera, 2012), while above 2000 m the number of ignition points was very limited, restricted to exceptional events such as those that occurred on Tenerife in 2018 and 2023, which began at around 1970 and 1605 m, respectively.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of the burned area by altitude. It can be observed that areas situated between 1000 and 1500 m concentrate the largest proportion of burned surface—exceeding 40% of the total—followed by the 750–1000 m and 1500–1750 m ranges, each accounting for approximately 20–25%. These altitudinal bands largely correspond to transition zones between laurel forest and Canary pine woodland, characterised by high biomass and continuous fuel. Although most fires ignite at mid-altitudes, the affected area often extends upslope, frequently reaching 2000 m. Above this threshold, burned area decreases considerably, representing only about 6–7% of the total. Nonetheless, some isolated events, such as the 2019 Gran Canaria fire, reached elevations exceeding 2200 m, affecting even high-mountain ecosystems. At the opposite end, areas below 500 m have been scarcely affected, with the exception of Tenerife (2021) and La Palma (2023). Taken together, ignition points and burned area distribution outline a consistent altitudinal concentration of LFFs between 750 and 1500 m.

Overall, these results outline a well-defined spatial footprint of LFFs in the archipelago, marked by their recurrence in mid-mountain belts and in municipalities with a strong rural–forest configuration.

3.2. Meteorological Conditions

Meteorological conditions play a fundamental role in the behaviour and propagation of forest fires in the Canary Islands. Among the most influential factors are temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, maximum wind gusts and the altitude of the thermal inversion layer. This section presents an analysis of the main meteorological conditions observed in the fires under study (

Table 3).

In general terms, temperature is the primary meteorological factor influencing the ignition and spread of forest fires. The average temperature on the ignition day of the analysed fires was 24.3 °C, with an average maximum temperature of 29.3 °C and an average minimum of 19.3 °C. The extreme values recorded corresponded to a maximum of 36.5 °C and a minimum of 16 °C. These data reflect high thermal conditions and a pronounced daily thermal amplitude, particularly relevant for fires occurring in mid-altitude zones. It is worth noting that in the case of the 2019 Tenerife fire, which occurred entirely above 2000 m a.s.l., temperatures were considerably lower than those typically recorded in events at lower elevations.

Another variable with a major influence on fire spread is relative humidity. On average, the mean relative humidity was 44.1%, with minimum values as low as 7% (Tenerife, July 2012) and maximum values up to 82% (Tenerife, 2022). The average minimum relative humidity was 23.7%, while the average maximum reached 68.9%, indicating significant variability among different fire episodes. The 2023 La Palma fire stood out for recording the highest humidity values, peaking at 98%, in contrast to the extremely dry conditions observed during the 2012 Tenerife fire, which registered the lowest humidity levels.

In terms of wind, although it is another determining factor in wildfire dynamics, the recorded average speeds were not exceptionally high. The mean wind speed was 3.0 m s−1 (≈10.8 km h−1), with an average gust of 10.9 m s−1 (≈39.2 km h−1). The maximum observed gust reached 22.2 m s−1 (≈80 km h−1), while the minimum was 5 m s−1 (≈18 km h−1). These values indicate that, although wind conditions were not extreme, in some episodes higher gusts coincided with complex topography, particularly in ravine and slope areas.

Regarding the altitude of the thermal inversion layer, the data show that during the analysed fires in the Canary Islands it was located at an average height of around 270 m a.s.l., with maximum values reaching 1034 m and minimum values of barely 120 m.

In this sense, the meteorological data indicate a recurring pattern of warm and dry conditions during ignition days.

3.3. Impacts of LFF

3.3.1. Land Use and Protected Areas

The impact of forest fires in the Canary Islands reveals a clear differentiation between protected and non-protected areas, as well as among the various land-use categories affected. Overall, the results show a strong concentration of impacts within areas subject to some form of environmental protection, highlighting the high exposure of the archipelago’s forest ecosystems.

The analysis of the thirteen fires recorded between 2012 and 2024 indicates that, on average, 81% of the burned area falls within protected natural areas, compared to 19% in unprotected zones (

Table 4). The largest fires—such as Gran Canaria 2019, Tenerife 2012 and Tenerife 2023—occurred almost entirely within protected areas (over 95% of the burned surface). In total, 29 protected natural areas were affected.

In terms of protection categories, Natural Parks were the most impacted, with a total of 20,345 ha burned, representing 42% of the total affected area. They were followed by Protected Landscapes, with 8894 ha (18.4%), and Rural Parks, with 4958 ha (10.2%). National Parks and Nature Reserves showed lower levels of damage, although still significant from an ecological perspective.

Regarding land-use categories derived from Corine Land Cover, coniferous forests account for the majority of the burned area—over 27,000 ha throughout the period—followed by shrub and scrub vegetation (approximately 6200 ha) and sparse or transitional vegetation (around 6000 ha). These land covers are typical of mid- and high-altitude zones, where the accumulation of biomass and fuel continuity promote fire spread.

Agricultural land also showed a notable degree of impact, with a total of 2896 ha burned, representing 2.4% of the total affected surface. Although relatively minor compared to forest areas, these impacts are mainly concentrated in rural and peri-urban interface zones, where buildings and traditional crops are common.

In terms of crop types, data reveal a clear predominance of vineyards, which account for more than 620 ha affected during the study period. This land use was particularly impacted during the Tenerife 2023 fire (over 300 ha) and the La Palma 2016 fire (around 70 ha), followed by La Gomera 2012 and Gran Canaria 2019. Vineyards were followed in extent by temperate fruit orchards, with approximately 470 ha, particularly in Gran Canaria 2017 and La Palma 2023, where they exceeded 50 ha and 37 ha, respectively. Fallow land and pastures also showed a relevant presence, with more than 230 ha affected, mainly across Gran Canaria 2019, Tenerife 2012 and Tenerife 2023, reflecting the frequency of fires in abandoned or transitional agricultural zones. Other crop types affected to a lesser extent included vegetable plots, subtropical fruit orchards, citrus groves and banana plantations, the latter with just over 2 ha burned in total. The fires with the largest burned agricultural areas were Gran Canaria 2019 (over 230 ha) and Tenerife 2023 (almost 990 ha), followed by La Palma 2016 and La Gomera 2012, both exceeding 60 ha.

In addition, the most recent period (2020–2023) reveals a shift in the spatial pattern of fires, with several events occurring outside protected areas (

Table 4), mainly in rural and peri-urban zones. The most notable cases correspond to La Palma 2020 and La Palma 2023, where over 90% of the burned surface was located in non-protected territory (99.9% and 91.7%, respectively). Land-use results therefore outline a clear predominance of burned area within protected forest landscapes.

3.3.2. LFF Severity

The results of the dNBR index reveal marked variability in the severity of forest fires recorded in the Canary Islands between 2012 and 2024 (

Figure 7). Mean dNBR values range between 0.19 and 0.44, reflecting a spectrum from low-impact to moderate-to-high levels of vegetation damage. In general terms, the most recent fires show higher average severity, particularly La Palma 2023 (mean dNBR = 0.39) and Gran Canaria 2017 (0.33), both of which recorded maximum values above 0.95, indicating the presence of extensive areas of high severity. In contrast, older events such as La Gomera 2012 (0.20) display lower values, associated with lower fire intensity and a greater proportion of unburned or regenerating areas. Overall, the severity results reveal a wide spectrum of burn responses across events, from predominantly low-severity fires to cases with extensive high-severity patches.

Figure 8 shows the percentage of burned area by the seven burn severity classes. Most fires fall within the low (30–50%) and low–moderate (20–35%) categories, while the extreme classes—high severity and high regrowth—represent much smaller proportions, generally below 10%. However, certain events such as La Palma 2023, Gran Canaria 2019 and Tenerife 2023 stand out for exhibiting a notable increase in moderate-to-high severity classes, with cumulative percentages exceeding 40% of their total burned area. Conversely, the La Gomera 2012 and La Palma 2016 fires show distributions dominated by low-severity and regrowth categories, exceeding 60% of their total surface area in these classes.

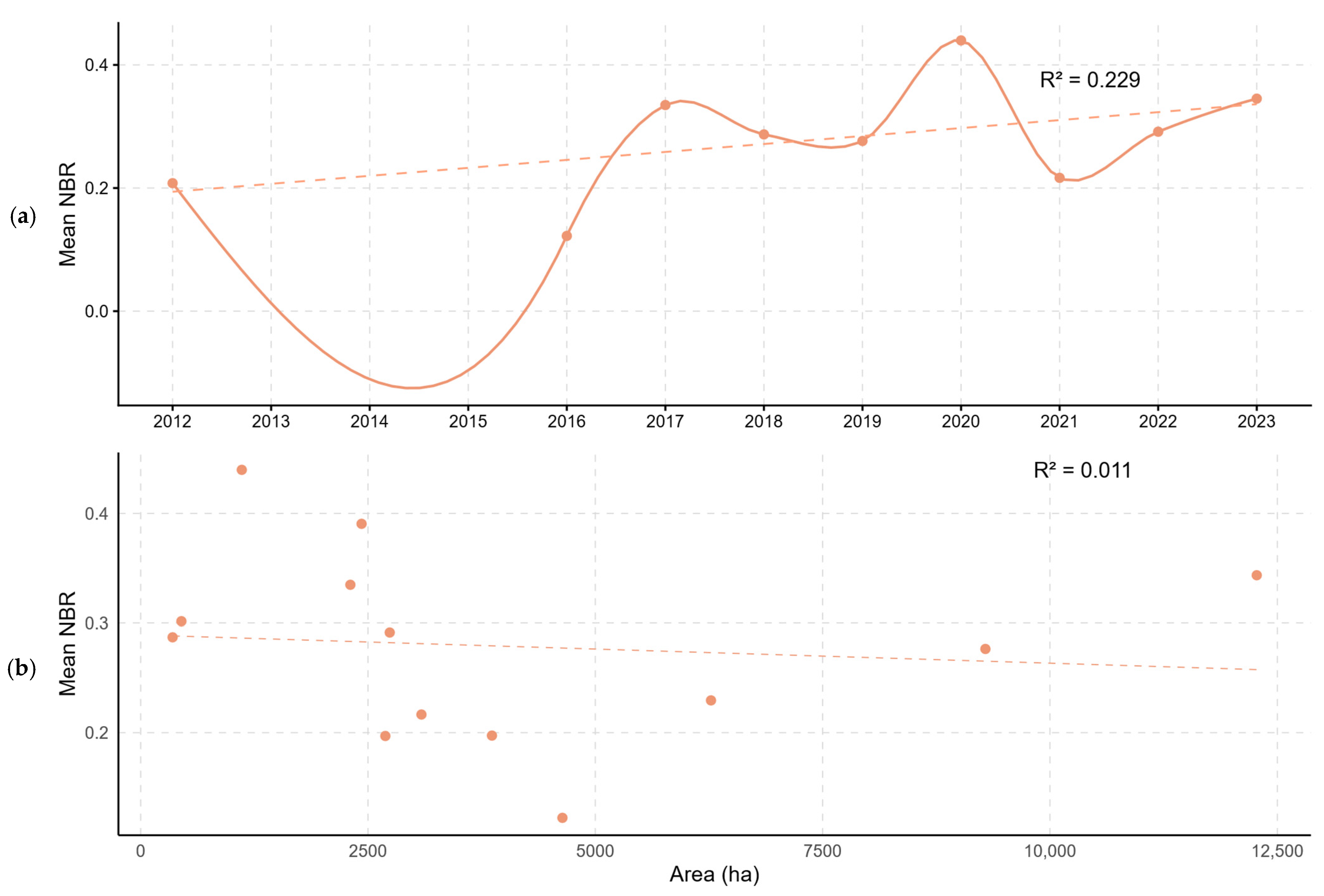

The temporal analysis of the mean dNBR index reveals a slight upward trend in wildfire severity in the Canary Islands during the 2012–2024 period (

Figure 9a), with a coefficient of determination of R

2 = 0.23. Although moderate, this increase suggests an evolution towards fires with greater ecological impact over the past decade. Annual mean dNBR values range from 0.12 (2016) to 0.39 (2020), reflecting marked interannual variability influenced by meteorological conditions, fuel spatial distribution, topographic features and the management capacity associated with each event. Among the years analysed, 2016 and 2012 recorded the lowest mean severity values, corresponding to smaller fires with rapid vegetation recovery, whereas the highest values were observed in 2020 (0.39) and 2023 (0.33), coinciding with the La Palma and Tenerife fires, respectively. The highest mean dNBR values coincide with years in which large fires affected extensive forested areas on the western islands.

The analysis of the relationship between burned area and mean fire severity (dNBR) does not reveal a significant correlation between the two variables (

Figure 9b). The obtained coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.01) indicates that fire size does not explain the variability in mean severity values. suggesting that a larger burned area is not necessarily associated with a greater impact on vegetation. Some small-scale fires, such as La Palma 2020 and La Gomera 2012, reached mean dNBR values comparable to or even higher than those recorded in larger events. such as Tenerife 2023 or Gran Canaria 2019. Temporally. the severity dataset exhibits a marked gradient. with several recent fires presenting higher proportions of mid- and high-severity classes

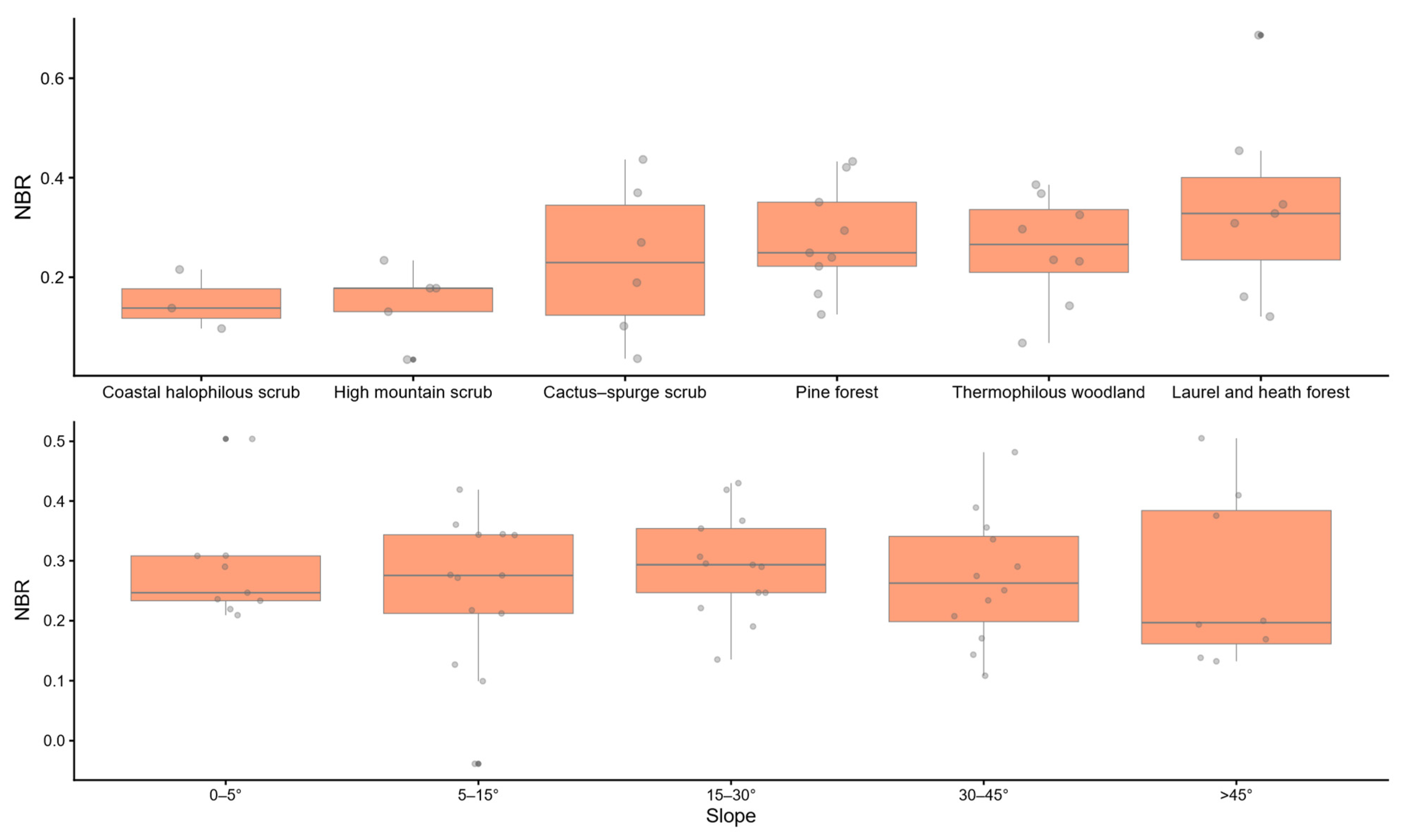

Across vegetation types, severity patterns remain highly variable, with distinct internal configurations depending on the dominant land cover. The analysis of burn severity by vegetation type and slope class highlights general ecological and topographic trends shaping fire behaviour in the Canary Islands (

Figure 10). In terms of vegetation, higher mean dNBR values were observed in laurel forest and fayal–brezal formations (0.33), followed by thermophilous forest (0.30) and Canary pine forest (0.29). These vegetation types are characterised by high biomass density and relatively continuous fuel loads, which favour fire spread and the development of higher burn severity. Conversely, summit scrub communities (0.17) and coastal halophilous scrub (0.15) show lower mean values, reflecting lower fuel availability and more discontinuous vegetation structures.

However, despite these apparent differences, the variability of severity values between individual fire events is high, and a one-way ANOVA did not reveal statistically significant differences in dNBR among vegetation types (F = 1.77, p = 0.15). This indicates that inter-fire variability outweighs differences attributable solely to vegetation type.

Regarding slope, mean severity increases with gradient up to intermediate slopes (15–30°), where the highest mean value is recorded (dNBR = 0.34), and subsequently decreases on steeper terrain. Lower severity values are observed on very steep slopes (>45°), likely associated with reduced fuel continuity and more heterogeneous fire spread conditions. As in the case of vegetation, statistical analysis did not identify significant differences in dNBR among slope classes (one-way ANOVA, F = 0.26, p = 0.90), reinforcing the importance of event-specific factors in controlling burn severity patterns.

Overall, these results suggest that, while certain vegetation types and topographic settings tend to be associated with higher or lower severity levels, burn severity in large forest fires is primarily driven by inter-event variability, likely linked to meteorological conditions and fire dynamics at the time of each event.

3.3.3. Direct Social Impacts

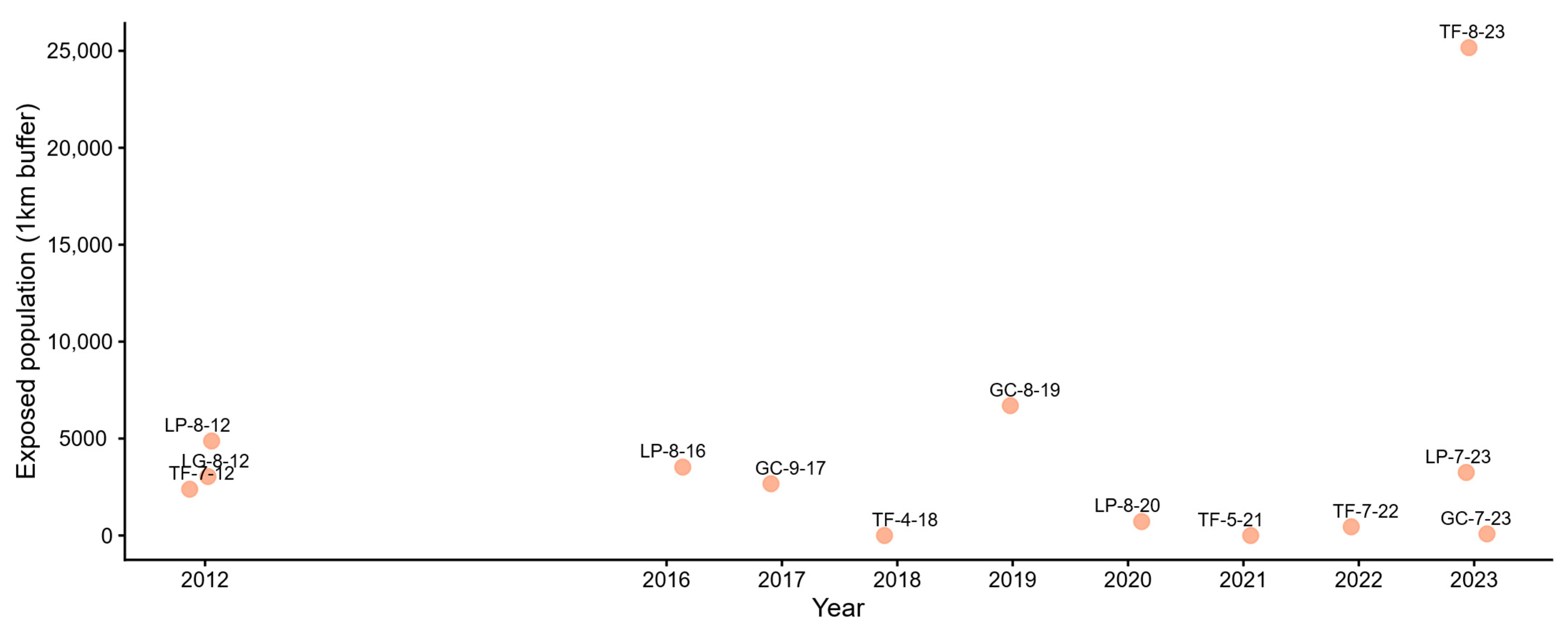

An additional dimension for assessing the social impact of large forest fires in the Canary Islands is population exposure. Potential exposure was estimated through the spatial intersection between fire perimeters and gridded population data, and further refined by considering a 1 km buffer around each fire perimeter to account for surrounding residential areas potentially affected by emergency measures. This approach allows population exposure to be analysed in a spatially explicit manner, independently of emergency response decisions.

The results show that population exposure within the burned perimeter is generally limited, with several fires presenting null or very low values, indicating that they occurred entirely in uninhabited or sparsely populated areas. For instance, the TF-4-18 and TF-5-21 fires intersected no resident population within the burned area, while other events such as LP-8-16 and LP-8-20 affected only a few hundred residents within the perimeter (201 and 279 people, respectively). By contrast, some recent events display substantially higher exposure values within the burned area, such as the July 2023 Tenerife fire, which intersected approximately 2582 residents.

When population exposure is assessed using a 1 km buffer around the fire perimeter, exposed population values increase markedly for most events and show strong temporal variability (

Figure 11). Early events in the series, such as the August 2012 fires in La Gomera and Tenerife, already present notable buffer-based exposure values (4874 and 2387 residents, respectively), despite limited exposure within the burned perimeter. In La Palma, the August 2016 fire intersected 201 residents within the burned area, while 3527 residents were located within 1 km of the perimeter. The July 2023 Tenerife fire represents an extreme case, with approximately 25,166 residents located within 1 km of the fire perimeter, clearly standing out from the rest of the series. These results indicate that, even when direct exposure within the burned area is limited, a substantial proportion of the resident population may be located in close proximity to large fires.

Evacuation data provide a complementary perspective on social impact, reflecting the operational response adopted during each event and offering additional context to the exposure estimates. Over the 2012–2024 period, approximately 43,160 people were evacuated, corresponding to around 1.94% of the total population of the archipelago. Evacuation values vary markedly between islands and individual fire events, both in absolute and relative terms, reflecting differences in population size, settlement patterns and exposure conditions.

Some of the most pronounced evacuation impacts were recorded on smaller islands, where relatively limited absolute numbers translate into high proportions of the resident population. The August 2012 La Gomera fire led to the evacuation of approximately 5000 people, equivalent to 22.37% of the island’s population, the highest relative evacuation rate observed in the series. In La Palma, the August 2016 fire resulted in around 2500 evacuees (3.07% of the island’s population), while the July 2023 fire led to approximately 4000 evacuations (4.77%). In contrast, the August 2023 Tenerife fire stands out for recording the highest absolute number of evacuees, with approximately 26,000 people displaced, corresponding to 2.7% of the island’s population.

Across events, high evacuation values tend to coincide with high buffer-based exposure estimates, indicating that evacuation measures were largely concentrated in areas with substantial residential presence in the vicinity of the fire perimeter. Conversely, fires characterised by low population exposure both within the burned perimeter and in the surrounding buffer generally correspond to limited or null evacuations, such as the July 2023 Gran Canaria fire or several events recorded between 2018 and 2021.