The Impact of Shared Team Task-Specific Experiences on Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Background: Team Effectiveness

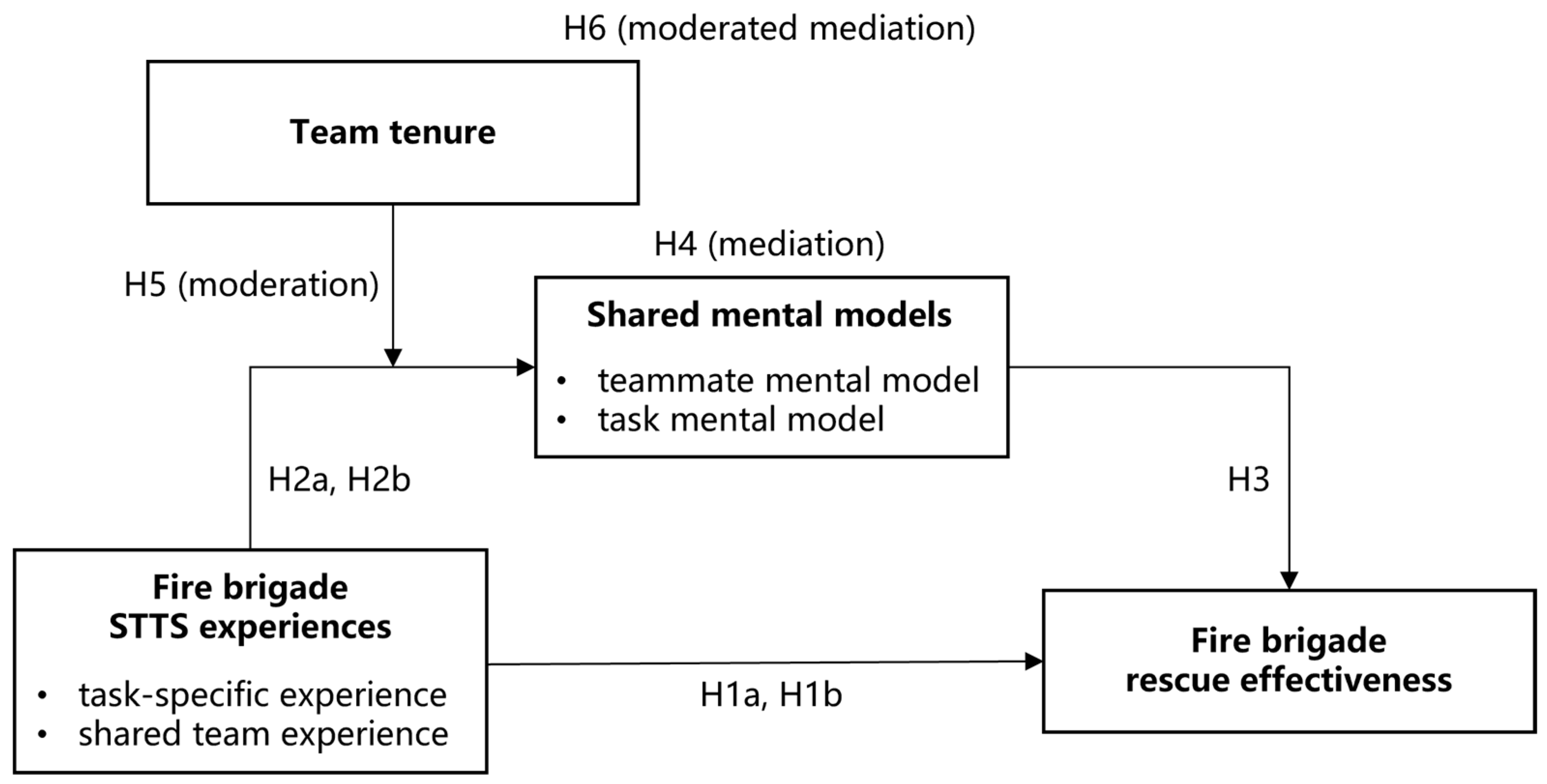

2.2. STTS Experiences and Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness

2.3. Shared Mental Models as a Mediator

2.4. Team Tenure as a Moderator

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Measures

- STTS experiences. We defined STTS experiences as the level of proficiency with which fire brigade members had previously performed similar tasks together. Luciano et al. in their study indexed STTS experience by quantifying the number of times surgeons collaborated to complete surgeries [10]. However, given that the current mission recording system of China’s fire squadrons counts attendance times on a squadron basis rather than on an individual basis, it is challenging to fully use objective evaluation methods to quantitatively evaluate firefighters’ STTS experience. Based on the prior discussions, STTS experience consists of two dimensions: task-specific experience and shared team experience. Task-specific experience reflects an individual’s knowledge base and skill proficiency in a particular task, with Rooney and Osipow‘s task-specific occupational self-efficacy scale providing a foundational reference for measuring this dimension [35]. For shared team experience, we referred to Rentsch et al.’s team experience scale, which measures the collective experiences among team members [8]. Combined with the research background of fire rescue tasks, STTS experiences were measured by a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (7), which comprises 12 items across the two dimensions: task-specific experience (8 items, e.g., “How proficient are you in operating emergency rescue equipment?”) and shared team experience (4 items, e.g., “The team frequently discusses and reflects on unsatisfactory combat missions”).

- Fire brigade rescue effectiveness. In this study, the concept of rescue effectiveness includes not only task performance but also the collaborative effectiveness of team members in rescue operations. Therefore, this research perspective involving firefighters’ perceptions of teamwork effectiveness warrants the use of subjective perception reports. These reports provide unique insights into operational challenges such as team coordination and command communication that cannot be fully captured by objective metrics such as response time alone. The use of subjective perceptions as indicators of system performance is well established in the fields of organizational behavior and emergency response. For instance, Huntsman et al., in their study on the ability of empowerment practices to enhance adaptive performance in emergency response organizations, employed self-report survey data from firefighters to capture their performance [36]. Similarly, Bonetto et al. used self-report questionnaires to assess individual creativity and reactions to emergency situations, further demonstrating the utility of subjective measures in this context [37]. To sum up, we measured the fire brigade rescue effectiveness from two perspectives: task performance and collaboration satisfaction. Referring to the work of [38], task performance was measured using two items (e.g., “The team works effectively and efficiently in achieving its goals”). Using another scale from [39], four items were used to capture collaboration satisfaction (e.g., “I am delighted to be a part of this team”). All items were designed on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (7).

- Shared mental models. The main methods for measuring shared mental models include questionnaires, cognitive mapping, and behavioral observation. Among these, questionnaire-based approaches have emerged as the most established and empirically validated method for assessing shared mental models. This methodology typically employs standardized scales to evaluate team members’ consensus regarding task-related and role-specific elements. While cognitive mapping or observational methods could offer complementary perspectives, they face practical barriers in high-stakes, real-world contexts like fire rescue operations and may be difficult to implement in large-scale studies. Considering our research objectives, we referred to the validated measurement instrument from [38] and used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (7) to measure shared mental models from two dimensions: teammate mental models (5 items, e.g., “I understand my teammates’ combat styles and habits”) and task mental models (5 items, e.g., “Team members have a consensus on the norms for task completion”).

- Team tenure. We defined team tenure as the length of time a firefighter has served in their current team. This variable was determined based on the personal data of the firefighters interviewed. In our survey, we collected this data through a single question: “How long have you been working with your current team?”

- Control variables. In order to control the influence of individual differences and environmental complexity on shared experience and team effectiveness, we incorporated several control variables to enhance the robustness of the results. First, individuals’ cognitive levels affect how they acquire and transform experiences as well as how they develop mental models [40]. Therefore, it is important to account for basic cognitive differences among firefighters. Specifically, we considered two individual factors: education level and current position. Education level reflects the basic cognitive ability of firefighters. Those with higher education may have advantages in information processing, problem solving, and knowledge integration, which in turn can influence how they learn from and apply task-related experiences [41]. Current position, on the other hand, pertains to firefighters’ roles within the team. Firefighters in different positions have different responsibilities, decision-making authority, and information interaction in task execution, all of which can affect their accumulation and sharing of task experience [42]. Second, environmental factors such as task difficulty are also important control variables. High-difficulty tasks typically require more complex cognitive processing and greater team collaboration, thus placing higher demands on the acquisition and application of experience. Additionally, such tasks may encourage more frequent communication and coordination among team members, promoting the development of shared mental models [43]. In summary, we selected education level, current position, and task difficulty as control variables. Education level and current position were obtained from the firefighters’ personal profile, while task difficulty was assessed based on the firefighters’ ratings of the difficulty of the tasks they had participated in over the past year.

3.3. Data Processing

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

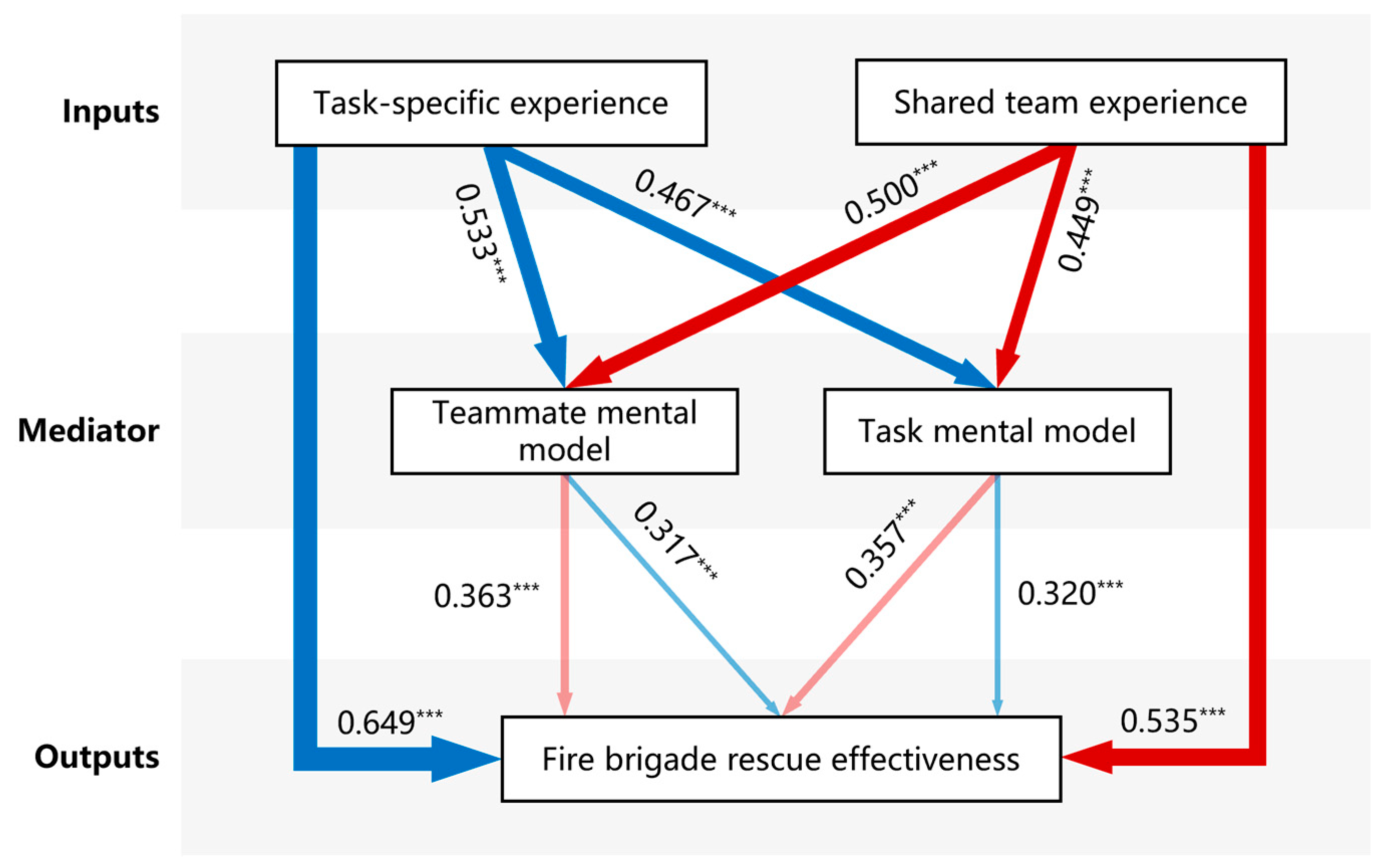

4.2. STTS Experiences and Rescue Effectiveness

4.3. Testing of the Mediation Effect

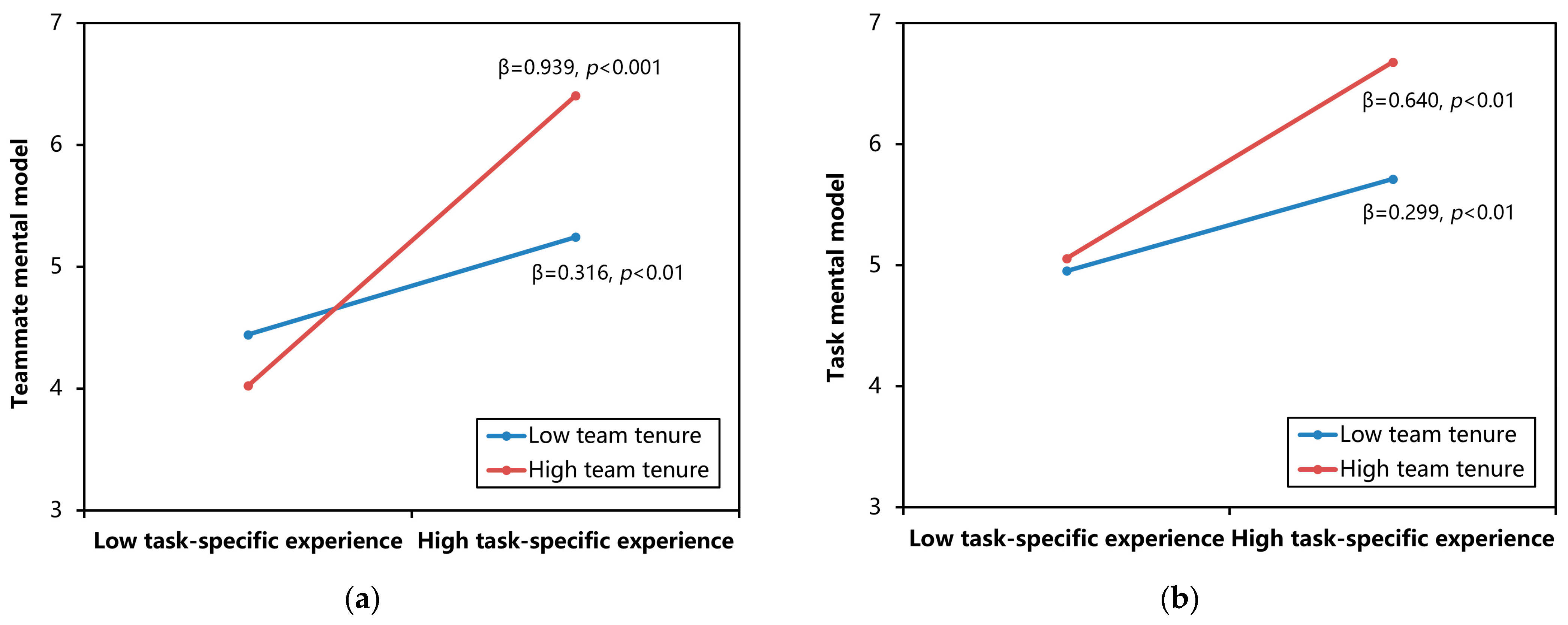

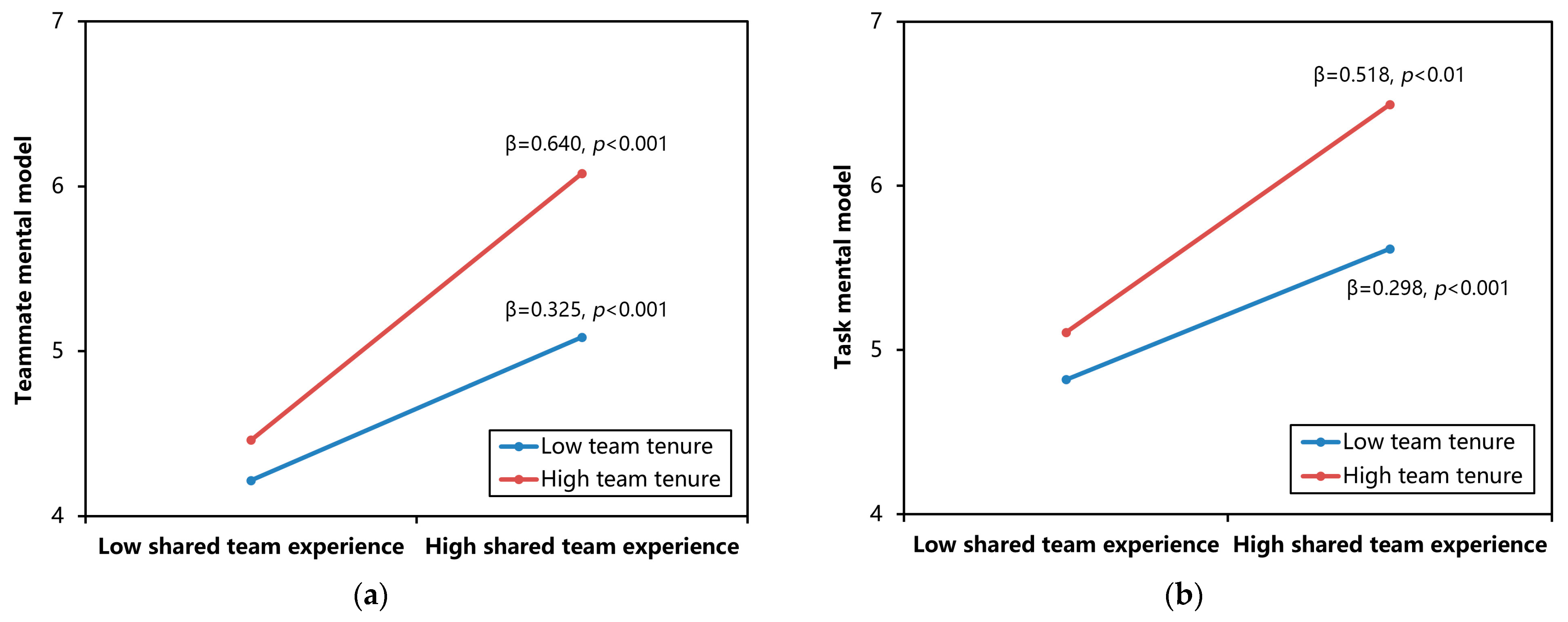

4.4. Testing of the Moderated Mediation Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Björcman, F.; Nilsson, B.; Elmqvist, C.; Fridlund, B.; Blom, Å.R.; Svensson, A. Fire and rescue services’ interaction with private forest owners during forest fires in Sweden: The incident commanders’ perspective. Fire 2024, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firefighter Fatalities in the US in 2020. Available online: https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/firefighter-fatalities-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Myriam, M.F.; Ignacio, R.G.; Antonio, D.P. Firefighter perception of risk: A multinational analysis. Saf. Sci. 2020, 123, 104545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Zarei, H.; Babamiri, M.; Kalatpour, O. Fatigue profile among petrochemical firefighters and its relationship with safety behavior: The moderating and mediating roles of perceived safety climate. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 28, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Raposo, J.; Farinha, J.T.; Raposo, H.; Reis, L. Study of the condition of forest fire fighting vehicles. Fire 2023, 6, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.H. Experiential learning—A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linda, A.; Ella, M.S. Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentsch, J.R.; Heffner, T.S.; Duffy, L.T. What you know is what you get from experience: Team experience related to teamwork schemas. Group. Organ. Manag. 1994, 19, 450–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, C.A.; Baker, D.P.; Salas, E. Measuring the importance of teamwork: The reliability and validity of job/task analysis indices for team-training design. Milit. Psychol. 1994, 6, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, M.M.; Bartels, A.L.; D’Innocenzo, L.; Maynard, M.T.; Mathieu, J.E. Shared team experiences and team effectiveness: Unpacking the contingent effects of entrained rhythms and task characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1403–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Heffner, T.S.; Goodwin, G.F.; Salas, E.; Cannon-Bowers, J.A. The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoverink, A.C.; Kirkman, B.L.; Mistry, S.; Rosen, B. Bouncing back together: Toward a theoretical model of work team resilience. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, N.J.; Gorman, J.C.; Duran, J.L.; Taylor, A.R. Team cognition in experienced command-and-control teams. J. Exp. Psychol.-Appl. 2007, 13, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeChurch, L.A.; Mesmer-Magnus, J.R. Measuring shared team mental models: A meta-analysis. Group. Dyn.-Theory Res. Pract. 2010, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Mohammed, S.; McGrath, J.E.; Florey, A.T.; Vanderstoep, S.W. Time matters in team performance: Effects of member familiarity, entrainment, and task discontinuity on speed and quality. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 633–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.; Maynard, T.M.; Rapp, T.; Gilson, L. Team effectiveness 1997–2007: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 410–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgen, D.R.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Johnson, M.; Jundt, D. Teams in organizations: From in-put-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.T.; Kennedy, D.M.; Resick, C.J. Teamwork in extreme environments: Lessons, challenges, and opportunities. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Hollingshead, A.B. Coordinating expertise among emergent groups responding to disasters. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Stagl, K.C.; Salas, E.; Pierce, L.; Kendall, D. Understanding team adaptation: A conceptual analysis and model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1189–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, D.P.; Hollingshead, A.B. Transactive memory systems in organizations: Matching tasks, expertise, and people. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlepage, G.; Robison, W.; Reddington, K. Effects of Task Experience and Group Experience on Group Performance, Member Ability, and Recognition of Expertise. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1997, 69, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckman, R.S.; Staats, B.R. Fluid tasks and fluid teams: The impact of diversity in experience and team familiarity on team performance. MSOM-Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2011, 13, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Mancuso, V.; Mohammed, S.; Tesler, R.; McNeese, M. Skilled and unaware: The interactive effects of team cognition, team metacognition, and task confidence on team performance. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 2017, 11, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonellato, M.; Iacopino, V.; Mascia, D.; Lomi, A. The partners of my partners: Shared collaborative experience and team performance in surgical teams. J. Manag. 2024, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.; DiazGranados, D.; Klein, C.; Burke, C.S.; Stagl, K.C.; Goodwin, G.F.; Halpin, S.M. Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 903–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannette, J.M.; Scoboria, A. Firefighter preferences regarding post-incident intervention. Work. Stress. 2008, 22, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bossche, P.; Gijselaers, W.; Segers, M.; Woltjer, G.; Kirschner, P. Team learning: Building shared mental models. Instr. Sci. 2011, 39, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ments, L.; Treur, J. Reflections on dynamics, adaptation and control: A cognitive architecture for mental models. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2021, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChurch, L.A.; Mesmer-Magnus, J.R. The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Pazos, P. How teams perform under emergent and dynamic situations: The roles of mental models and backup behaviors. Team Perform. Manag. 2021, 27, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiger, K.; Wenzel, L.H. Conceptual development and empirical evaluation of measures of shared mental models as indicators of team effectiveness. In Team Performance Assessment and Measurement: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Brannick, M.T., Salas, E., Prince, C., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tesluk, P.E.; Jacobs, R.R. Toward an integrated model of work experience. Pers. Psychol. 1998, 51, 321–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Ferzandi, L.; Hamilton, K. Metaphor no more: A 15-year review of the team mental model construct. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 876–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, R.A.; Osipow, S.H. Task-specific occupational self-efficacy scale: The development and validation of a prototype. J. Vocat. Behav. 1992, 40, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntsman, D.; Greer, A.; Murphy, H.; Haynes, S. Enhancing adaptive performance in emergency response: Empowerment practices and the moderating role of tempo balance. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, E.; Pavani, J.B.; Dezecache, G.; Pichot, N.; Guiller, T.; Simoni, M.; Fointiat, V.; Arciszewski, T. Creativity in emergency settings. Creativ. Res. J. 2024, 36, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.C.; Klein, K.J. Team mental models and team performance: A field study of the effects of team mental model similarity and accuracy. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Cant, R.; Porter, J.; Sellick, K.; Somers, G.; Kinsman, L.; Nestel, D. Rating medical emergency teamwork performance: Development of the team emergency assessment measure (TEAM). Resuscitation 2010, 81, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olschewski, S.; Luckman, A.; Mason, A.; Ludvig, E.A.; Konstantinidis, E. The future of decisions from experience: Connecting real-world decision problems to cognitive processes. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 19, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Carrillo, B.; Katovich, K.; Bunge, S.A. Does higher education hone cognitive functioning and learning efficacy? Findings from a large and diverse sample. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.D.S.; Bonner, B.L. How diverse task experience affects both group and subsequent individual performance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 48, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaatouq, A.; Alsobay, M.; Yin, M.; Watts, D.J. Task complexity moderates group synergy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2101062118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallinckrodt, B.; Abraham, W.T.; Wei, M.; Russell, D.W. Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, G. Industry and startup experience on entrepreneur forecast performance in new firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhuysen, G.A. Structuring change: Familiarity and formal interventions in problem6solving groups. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mulé, E.; Cockburn, B.S.; McCormick, B.W.; Zhao, P. Team tenure and team performance: A meta-analysis and process model. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 73, 151–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Wang, M.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J. Nonlinear effects of team tenure on team psychological safety climate and climate strength: Implications for average team member performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 940–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Mossel, E.; Strack, P.; Tamuz, O. Rational groupthink. Q. J. Econ. 2021, 136, 621–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managment team learning orientation and business unit performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, M.; Furlan, A.; Netland, T. Unlocking team performance: How shared mental models drive proactive problem-solving. Hum. Relat. 2024, 78, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rensburg, J.J.; Santos, C.M.; de Jong, S.B. Sharing time and goals in dyads: How shared tenure and goal interdependence influence perceived shared mental models. Team Perform. Manag. 2023, 29, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task-specific experience | 5.223 | 1.267 | 1.000 | |||||

| Shared team experience | 4.855 | 1.338 | 0.438 * | 1.000 | ||||

| Teammate mental model | 5.056 | 1.314 | 0.515 * | 0.510 * | 1.000 | |||

| Task mental model | 5.079 | 1.218 | 0.484 * | 0.493 * | 0.541 * | 1.000 | ||

| Team tenure | 2.396 | 1.226 | 0.384 * | 0.360 * | 0.494 * | 0.473 * | 1.000 | |

| Fire brigade rescue effectiveness | 5.142 | 1.341 | 0.613 * | 0.532 * | 0.628 * | 0.607 * | 0.343 * | 1.000 |

| Teammate Mental Model | Task Mental Model | Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| Constant | 2.346 *** | 2.599 *** | 3.213 *** | 3.381 *** | 0.034 | 0.323 |

| (7.280) | (8.312) | (10.591) | (11.583) | (0.116) | (1.084) | |

| Education | 0.048 | 0.067 | −0.115 | −0.098 | 0.047 | 0.054 |

| (0.594) | (0.820) | (−1.509) | (−1.289) | (0.738) | (0.806) | |

| Task difficulty | 0.015 | 0.006 | −0.044 | −0.053 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| (0.303) | (0.125) | (−0.931) | (−1.125) | (0.128) | (0.246) | |

| Current position | −0.053 | −0.024 | −0.079 * | −0.053 | 0.018 | 0.034 |

| (−1.306) | (−0.599) | (−2.082) | (−1.414) | (0.576) | (1.029) | |

| Task-specific experience | 0.533 *** | 0.467 *** | 0.331 *** | |||

| (12.688) | (11.804) | (8.164) | ||||

| Shared team experience | 0.500 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.193 *** | |||

| (12.447) | (11.969) | (4.807) | ||||

| Teammate mental model | 0.317 *** | 0.363 *** | ||||

| (7.798) | (8.592) | |||||

| Task mental model | 0.320 *** | 0.357 *** | ||||

| (7.419) | (7.878) | |||||

| R2 | 0.269 | 0.262 | 0.246 | 0.251 | 0.563 | 0.522 |

| F | 41.199 *** | 39.677 *** | 36.445 *** | 37.438 *** | 95.559 *** | 81.115 *** |

| Predictors | Teammate Mental Model | Task Mental Model | Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Constant | 4.571 ** (8.623) | [3.429, 5.298] | 3.427 ** (7.099) | [2.567, 4.260] | 4.366 ** (8.508) | [2.759, 4.580] | 4.007 ** (8.796) | [2.693, 4.300] | 0.034 (0.116) | [−0.532, 0.600] | 0.323 (1.084) | [−0.263, 0.907] |

| Education | −0.016 (−0.219) | [−0.173, 0.141] | 0.01 (0.139) | [−0.141, 0.162] | −0.164 ** (−2.325) | [−0.304, −0.025] | −0.147 * (−2.083) | [−0.281, −0.012] | 0.047 (0.738) | [−0.079, 0.174] | 0.054 (0.806) | [−0.078, 0.186] |

| Task difficulty | 0.047 (1.031) | [−0.047, 0.140] | 0.042 (0.895) | [−0.052, 0.135] | −0.018 (−0.418) | [−0.141, −0.025] | −0.023 (−0.515) | [−0.108, 0.063] | 0.005 (0.128) | [−0.073, 0.084] | 0.01 (0.246) | [−0.072, 0.093] |

| Current position | −0.062 (−1.718) | [−0.158, 0.033] | −0.028 (−0.745) | [−0.122, 0.067] | −0.083 * (−2.361) | −0.057 (−1.613) | [−0.124, 0.011] | 0.018 (0.576) | [−0.045, 0.081] | 0.034 (1.029) | [−0.031, 0.100] | |

| Task-specific experience | 0.018 (0.228) | [−0.126, 0.190] | 0.136 (1.742) | [−0.001, 0.306] | 0.331 ** (8.164) | [0.251, 0.410] | ||||||

| Shared team experience | 0.191 * (2.842) | [0.054, 0.344] | 0.192 ** (2.736) | [0.061, 0.336] | 0.193 ** (4.807) | [0.114, 0.273] | ||||||

| Team tenure | −1.176 ** (−4.061) | [−1.703, −0.568] | −0.301 (−1.233) | [−0.771, 0.186] | −0.508 (−1.813) | [−0.998, 0.109] | −0.199 (−0.865) | [−0.650, 0.258] | ||||

| Task-specific experience × team tenure | 0.254 ** (5.404) | [0.155, 0.340] | 0.139 ** (3.046) | [0.038, 0.218] | ||||||||

| Shared team experience × team tenure | 0.114 ** (2.842) | [0.034, 0.191] | 0.090 * (2.377) | [0.014, 0.164] | ||||||||

| Teammate mental model | 0.317 ** (7.798) | [0.237, 0.397] | 0.363 ** (8.592) | [0.280, 0.446] | ||||||||

| Task mental model | 0.320 ** (7.419) | [0.235, 0.405] | 0.357 ** (7.878) | [0.267, 0.445] | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.41 | 0.383 | 0.356 | 0.36 | 0.563 | 0.522 | ||||||

| F | 51.557 *** | 46.071 *** | 41.071 *** | 41.787 *** | 95.559 *** | 81.115 *** | ||||||

| Path of Mediation | Level | Effect Value | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task-specific experience—teammate mental model—fire brigade rescue effectiveness | Low level (−1SD) | 0.100 | 0.022 | 0.061 | 0.149 |

| Mean | 0.199 | 0.035 | 0.134 | 0.272 | |

| High level (+1SD) | 0.298 | 0.059 | 0.193 | 0.425 | |

| Task-specific experience—task mental model—fire brigade rescue effectiveness | Low level (−1SD) | 0.095 | 0.025 | 0.049 | 0.148 |

| Mean | 0.150 | 0.029 | 0.098 | 0.21 | |

| High level (+1SD) | 0.204 | 0.048 | 0.120 | 0.307 | |

| Shared team experience—teammate mental model—fire brigade rescue effectiveness | Low level (−1SD) | 0.118 | 0.026 | 0.073 | 0.173 |

| Mean | 0.169 | 0.028 | 0.120 | 0.228 | |

| High level (+1SD) | 0.220 | 0.043 | 0.146 | 0.314 | |

| Shared team experience—task mental model—fire brigade rescue effectiveness | Low level (−1SD) | 0.106 | 0.028 | 0.058 | 0.166 |

| Mean | 0.146 | 0.028 | 0.096 | 0.204 | |

| High level (+1SD) | 0.185 | 0.041 | 0.113 | 0.272 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qian, Y.-Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Fan, C. The Impact of Shared Team Task-Specific Experiences on Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness. Fire 2025, 8, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8040136

Qian Y-Y, Zhuang Y, Wang Z-H, Fan C. The Impact of Shared Team Task-Specific Experiences on Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness. Fire. 2025; 8(4):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8040136

Chicago/Turabian StyleQian, Yang-Yang, Yue Zhuang, Zi-Hao Wang, and Chao Fan. 2025. "The Impact of Shared Team Task-Specific Experiences on Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness" Fire 8, no. 4: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8040136

APA StyleQian, Y.-Y., Zhuang, Y., Wang, Z.-H., & Fan, C. (2025). The Impact of Shared Team Task-Specific Experiences on Fire Brigade Rescue Effectiveness. Fire, 8(4), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8040136