Influence of Aging on Thermal Runaway Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Experiments and Simulations for Engineering Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental and Numerical Model Design

2.1. Physical Experiment Design

2.1.1. Aged LIB Module for Experimental Design

2.1.2. Heat Transfer Module for Aged LIB Experimental Design

2.2. Simulation Model for Aged LIBs

3. Experimental Implementation of the Module

- (1)

- Attach a temperature sensor to the lithium-ion battery and place it in the test chamber.

- (2)

- Activate the ventilation system and start the temperature data acquisition unit.

- (3)

- Set the heater to the target temperature and begin heating until battery failure occurs.

- (4)

- Record the battery temperature and observe external physical changes throughout the thermal runaway process.

- (5)

- Upon finishing the experiment, implement appropriate fire safety measures and clean the test platform with alcohol.

- (6)

- Analyze the collected data to determine the battery temperature profile.

- (1)

- Initiate preheating in advance and activate the cone heater to reach 40 kW/m2.

- (2)

- Engage the pump, fan and load cell, and then adjust oxygen concentration to 20.95%.

- (3)

- Weigh the battery.

- (4)

- Place the battery, open the insulating shutter beneath the heater, and commence heating until flame extinction.

- (1)

- Preparation: Set the necessary geometric and physical parameters.

- (2)

- Geometry: Construct a cylinder representing the LIB and add a cylindrical coordinate system.

- (3)

- Model Definition: Add domain probes to detect changes in physical quantities. Add a nonlocal coupling average to treat the battery as a whole with uniform temperature. Define variables for side reactions and the aging reaction.

- (4)

- Physics Setup: Select the Solid Heat Transfer physics interface. Add nodes for solid materials, initial values, thermal insulation, heat sources, and heat flux. Select the Global ODE and DAE interface to add reactant concentrations for each side reaction. Parameters are sourced from the literature [32,34], as listed in Table 5.

- (5)

- Computation Settings: The time unit is set to seconds, with output times defined as range (0, 20, 10,000).

4. Simulation Results Discussion

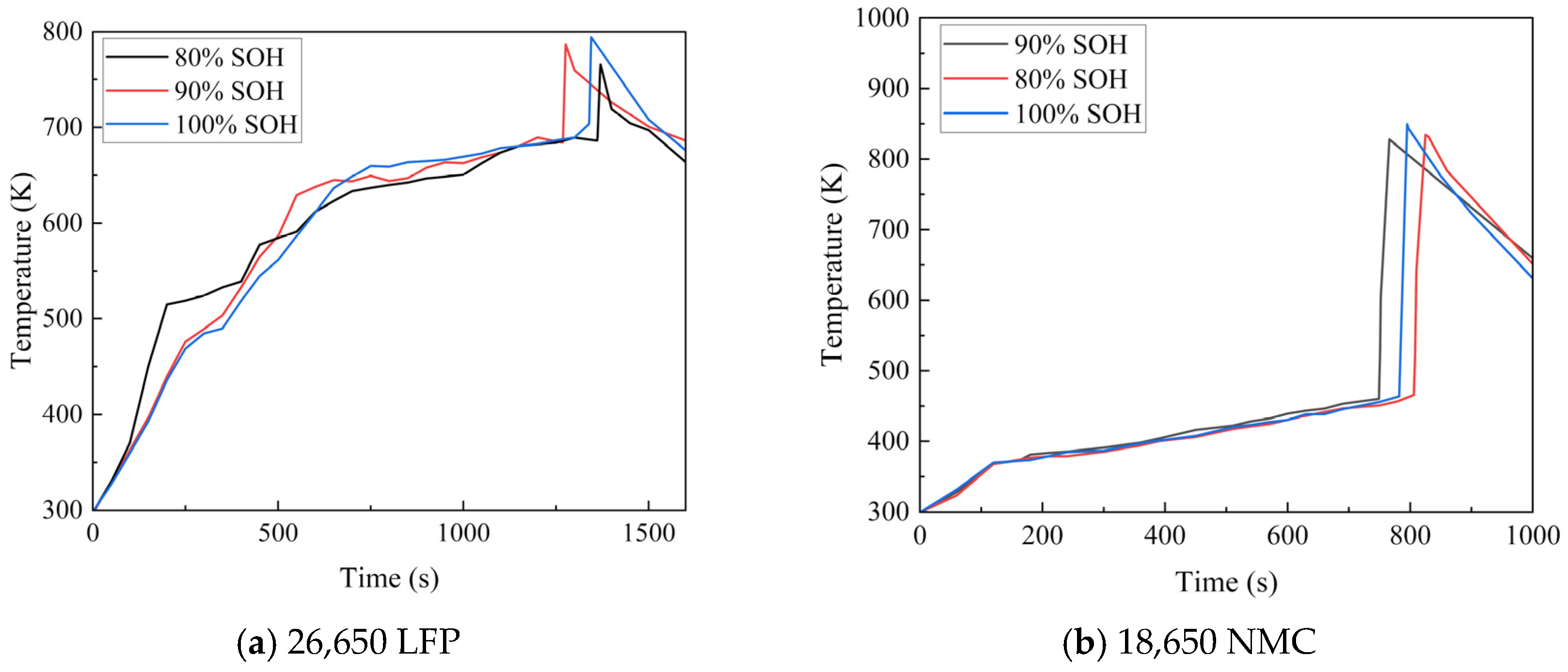

4.1. Thermal Runaway Experiments on Aged Batteries

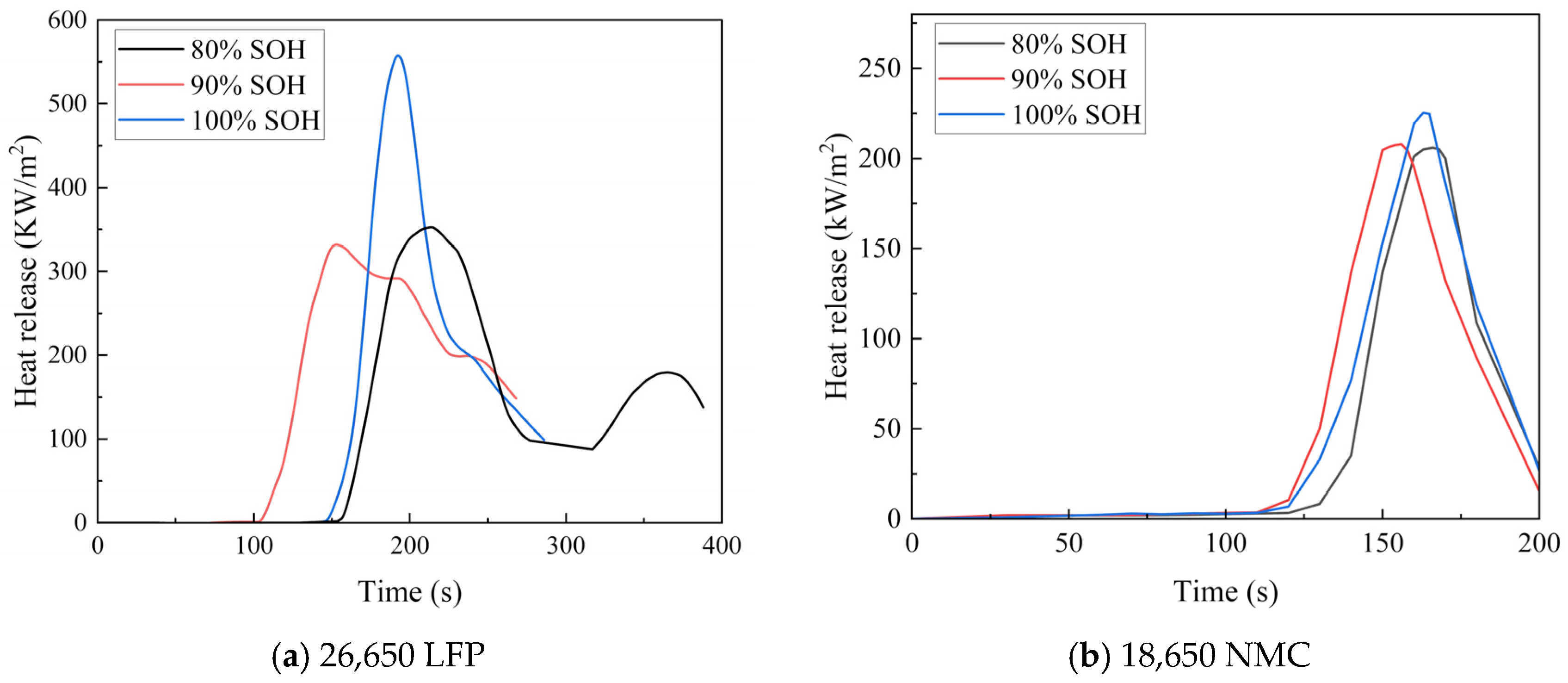

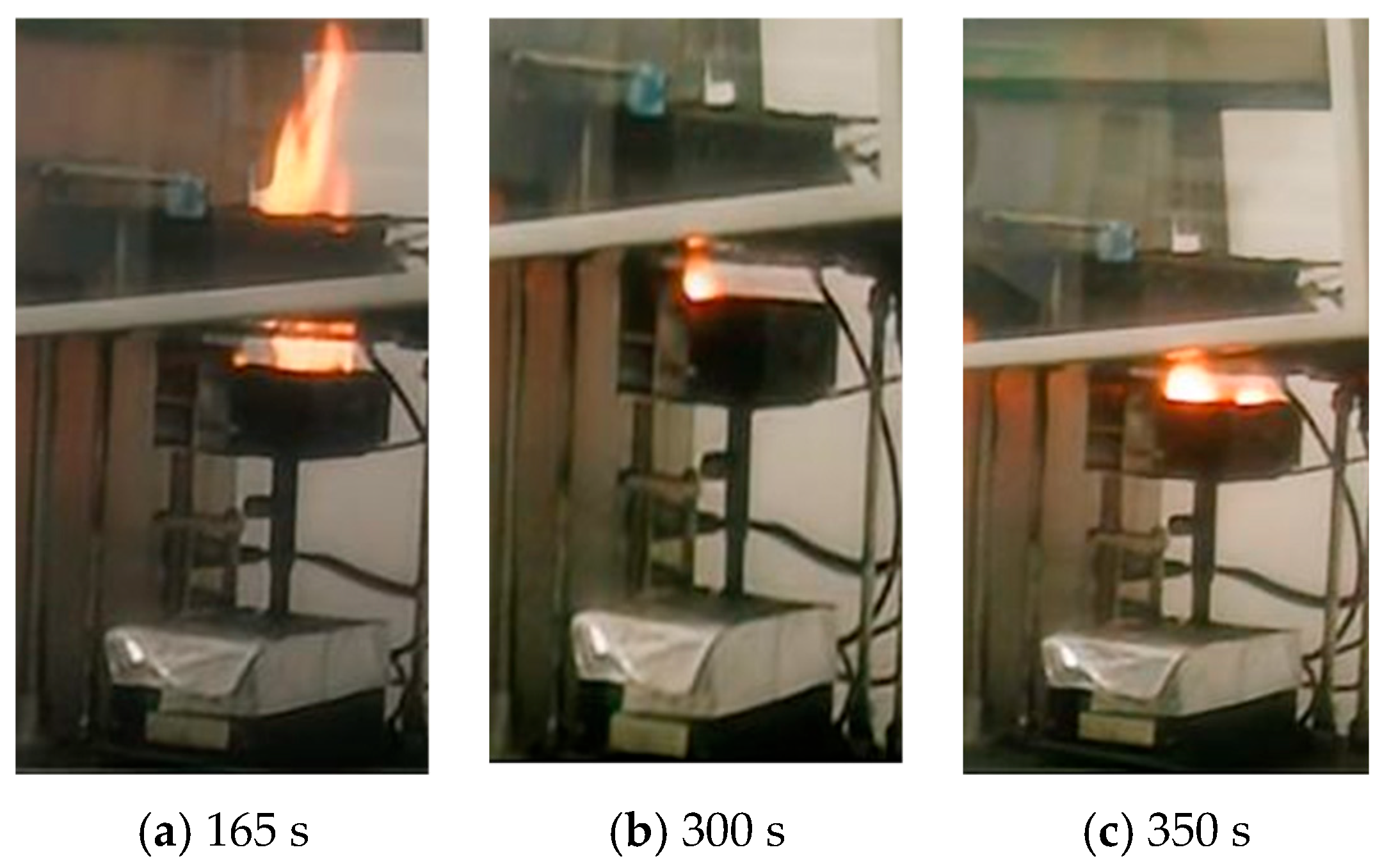

4.2. Influence of Aging on the Heat Release Rate of LIBs

4.3. Influence of Aging Degree on LIB Thermal Runaway

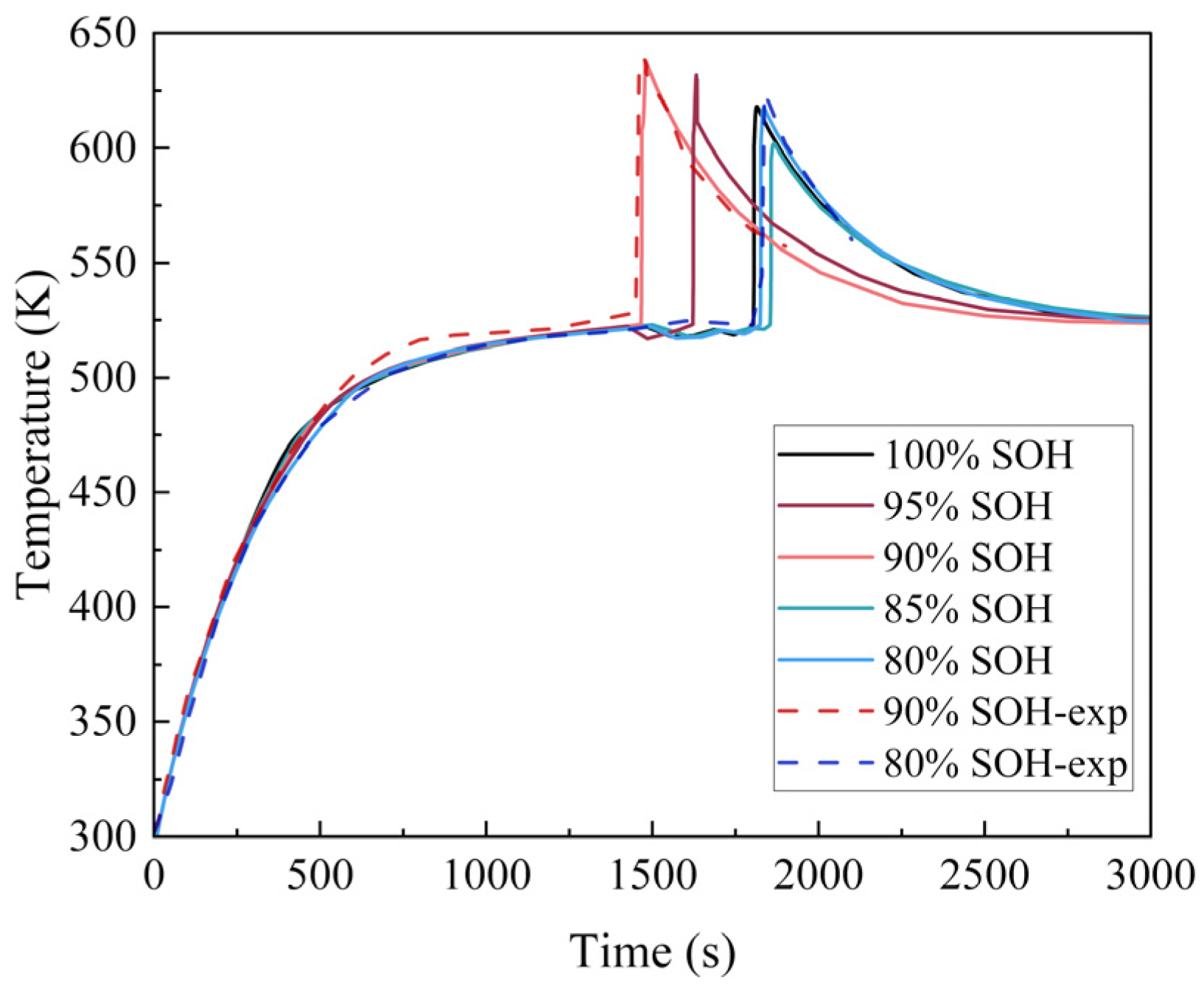

5. Conclusions

- (1)

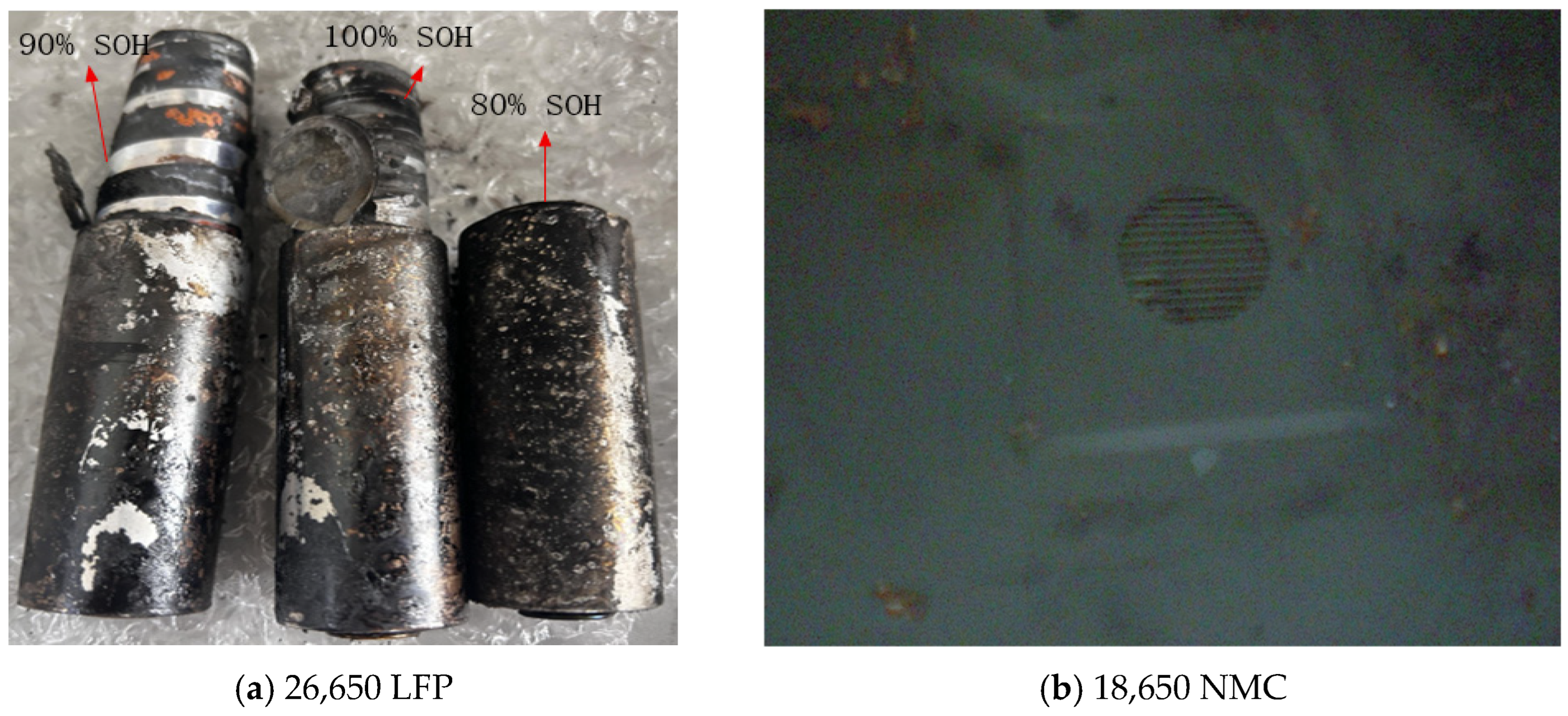

- The external heating tests on NMC and LFP batteries revealed distinct thermal runaway curves, which were attributed to differences in their form factor, energy density, and chemistry. The severe rupture of the NMC batteries post-test presented a striking contrast to the structurally intact LFP batteries. Despite these differences, a notable similarity emerged across aging states: mild aging led to an earlier onset of thermal runaway in both battery types. Conversely, the new batteries reached the highest temperatures due to their higher proportion of organic compounds, which promoted more intense reactions.

- (2)

- The cone calorimeter tests provided deeper insights into the impact of aging on thermal runaway in LFP and NMC batteries. Aligning with the external heating experiments, the heat release rate (HRR) curves of aged LFP batteries showed low similarity, whereas those of NMC batteries maintained high consistency. This divergence arose because thermal runaway in LFP batteries involved safer, staged internal reactions, while in NMC batteries, it was an irreversible chain reaction. Both the mass loss and HRR data across different aging states confirmed an inverse correlation between the aging degree and the amount of active material consumed during thermal runaway.

- (3)

- To solidify the pedagogical outcomes, simulations were introduced to analyze lithium-ion battery thermal runaway from a microscopic perspective. These models vividly demonstrated the impact of SEI growth on thermal runaway in LFP batteries at different aging states, providing deeper mechanistic insights: the competition between the destabilizing effect of a thickened, unstable SEI layer at moderate aging and the consumption of active material at advanced aging stages.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attia, P.M.; Moch, E.; Herring, P.K. Challenges and opportunities for high-quality battery production at scale. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichtner, M.; Edstrom, K.; Ayerbe, E.; Berecibar, M.; Bhowmik, A.; Castelli, I.E.; Clark, S.; Dominko, R.; Erakca, M.; Franco, A.A.; et al. Rechargeable Batteries of the Future-The State of the Art from a BATTERY 2030+Perspective. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2102904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Mallarapu, A.; Lim, J.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Han, Y.; Choi, B.-H. Observation and modeling of the thermal runaway of high-capacity pouch cells due to an internal short induced by an indenter. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilaki, M.; Sahraei, E. Modeling state-of-charge dependent mechanical response of lithium-ion batteries with volume expansion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preger, Y.; Torres-Castro, L.; Rauhala, T.; Jeevarajan, J. Perspective—On the Safety of Aged Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 030507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguemont, J.; Barde, F. A critical review of lithium-ion battery safety testing and standards. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 231, 121014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.; Liu, X.; Qu, J.; Zhao, J.; Huo, Y.; Qu, Z.; Rao, Z. Recent advances of thermal safety of lithium-ion battery for energy storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 31, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Jiang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, S.; et al. Characterization on thermal runaway of commercial 18650 lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles: A review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, F.; Wang, Z. An overview on thermal safety issues of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicle application. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 23848–23863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuchakallaya, I.; Saechan, P. Numerical study of a pressurized gas cooling system to suppress thermal runaway propagation in high-energy-density lithium-ion battery packs. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhn, E.; Braxtan, N.; Chen, S.E.; Bombik, A.; Zhao, T.; Ma, L.; Sherman, J.; Roghani, S. Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal Runaway Suppression Using Water Spray Cooling. Energies 2025, 18, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Monsalve-Serrano, J.; Marco-Gimeno, J.; Guaraco-Figueira, C. Experimental and numerical analysis of heat and gas generation during thermal runaway in NMC811 lithium-ion batteries under thermal abuse and inert conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 253, 127536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.M.; Dubaniewicz, T.; Zlochower, I.; Thomas, R.; Rayyan, N. Experimental study on thermal runaway and vented gases of lithium-ion cells. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 144, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerger, A.; Mertens, J.; Wenzl, H. Thermal runaway and thermal runaway propagation in batteries: What do we talk about? J. Energy Storage 2019, 24, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.S.M.; Tohir, M.Z.M. Characterisation of thermal runaway behaviour of cylindrical lithium-ion battery using Accelerating Rate Calorimeter and oven heating. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galushkin, N.E.; Yazvinskaya, N.N.; Galushkin, D.N. Causes and mechanism of thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries, contradictions in the generally accepted mechanism. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, D.; Karimi, F.; Schmiegel, J.P.; Lübke, M.; Lechtenfeld, C.-T.; Kessen, D.; Schrief, L.; Kwade, A. Are aged cells safer than fresh cells? A comprehensive study of 21700-type NCA/Gr-Si battery cells through thermal stability test, cathode material analysis, and hazard level assessment. J. Energy Storage 2025, 652, 237488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallarapu, A.; Sunderlin, N.; Boovaragavan, V.; Tamashiro, M.; Peabody, C.; Pelloux-Gervais, T.; Li, X.X.; Sizikov, G. Effects of Trigger Method on Fire Propagation during the Thermal Runaway Process in Li-ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 040514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talele, V.; Patil, M.S.; Panchal, S.; Fraser, R.; Fowler, M. Battery thermal runaway propagation time delay strategy using phase change material integrated with pyro block lining: Dual functionality battery thermal design. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65, 107253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, S.T.; Chen, C.X.; Rojaee, R.; Doherty, P.; Oh, Y.S.; Galazutdinova, Y.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Al-Hallaj, S. Enhancing thermal safety in lithium-ion battery packs through parallel cell ‘current dumping’ mitigation. Appl. Energy 2021, 286, 116495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Monsalve-Serrano, J.; Dreif, A.; Guaraco-Figueira, C. Multiphysics integrated model of NMC111 battery module for micro-mobility applications using PCM as intercell material. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 249, 123421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A.; Utgikar, V.; Belt, J. A Study of Thermal Runaway Mechanisms in Lithium-Ion Batteries and Predictive Numerical Modeling Techniques. Batteries 2024, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Bai, Z. Safety Methods for Mitigating Thermal Runaway of Lithium-Ion Batteries—A Review. Fire 2025, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.K.; Qi, W.W.; Wang, J.; Shen, J. Closed-Loop Multimodal Framework for Early Warning and Emergency Response for Overcharge-Induced Thermal Runaway in LFP Batteries. Fire 2025, 8, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, P.; Bhattacharya, J. Review-Understanding the Thermal Runaway Behavior of Li-Ion Batteries through Experimental Techniques. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A2165–A2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.X.; Zhao, L.Y.; Zhao, J.J.; Xu, G.; Liu, H.; Chen, M. An Experimental Study on the Thermal Runaway Propagation of Cycling Aged Lithium-Ion Battery Modules. Fire 2024, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talele, V.; Morali, U.; Patil, M.S.; Panchal, S.; Fraser, R.; Fowler, M.; Thorat, P.; Gokhale, Y.P. Computational modelling and statistical evaluation of thermal runaway safety regime response on lithium-ion battery with different cathodic chemistry and varying ambient condition. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 146, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lin, C.; Fan, B.; Wang, F.; Lao, L.; Yang, P. A new method to determine the heating power of ternary cylindrical lithium ion batteries with highly repeatable thermal runaway test characteristics. J. Power Sources 2020, 472, 228503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.S.; Feng, X.N.; Liu, L.S.; Hsu, H.; Lu, L.; Wang, L.; He, X.; Ouyang, M. Investigating the relationship between internal short circuit and thermal runaway of lithium-ion batteries under thermal abuse condition. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 34, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.M.; Wang, C.; Luan, W.L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H. Thermal runaway behaviors of Li-ion batteries after low temperature aging: Experimental study and predictive modeling. J. Energy Storage 2023, 66, 107451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Pastor, J.; Monsalve-Serrano, J.; Golke, D. Cell-to-cell dispersion impact on zero-dimensional models for predicting thermal runaway parameters of NCA and NMC811. Appl. Energy 2024, 369, 123571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abada, S.; Petit, M.; Lecocq, A.; Marlair, G.; Sauvant-Moynot, V.; Huet, F. Combined experimental and modeling approaches of the thermal runaway of fresh and aged lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 399, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.W.; He, X.; Restuccia, F.; Rein, G. Numerical Study of Self-Heating Ignition of a Box of Lithium-Ion Batteries During Storage. Fire Technol. 2020, 56, 2603–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Pesaran, A.; Spotnitz, R. A three-dimensional thermal abuse model for lithium-ion cells. J. Power Sources 2007, 170, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Jiang, F.M. Thermal safety of lithium-ion batteries with various cathode materials: A numerical study. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2016, 103, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, B.; Daniel, W.; Ulrike, K. Impact of electrolyte impurities and SEI composition on battery safety. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 13783–13798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date | Incident Description | Casualties/Losses |

|---|---|---|

| 23 February 2024 | Major fire accident in Jiangsu Province in China caused by thermal runaway of large-format LIBs. | 15 deaths, 2 serious injuries |

| April 2023 | Fire triggered by LIB thermal runaway due to overcharging, involving exothermic reactions on electrodes and internal short circuits by Li dendrites. | No casualties |

| 16 April 2022 | Explosion at an electrochemical energy storage station in Beijing South Fourth Ring Road of China, involving 25 MWh LFP batteries, potentially due to aging, environmental, installation, and product factors. | 3 deaths, 1 injury |

| 13 June 2023 | Fire at a warehouse in Lanzhou City, Gansu Province, China, storing approximately 200 tons of waste LIBs; fire area about 200 m2 | No casualties |

| 16 April 2021 | Fire in a battery cabinet in Sichuan, China; direct cause was internal short circuit leading to thermal runaway in LFP batteries. | No casualties |

| Parameter | LFP Battery | NMC Battery |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity (Ah) | 2.3 | 3.3 |

| Weight (g) | 77 ± 1 | 49 ± 1 |

| Size (mm) | 26 × 65 | 18 × 65 |

| Model | Highlight | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Lumped heat generation model [30] | The model does a good job of simulating the complete thermal runaway process using a three-stage approach based on experiments | It fails to accurately describe the impact of internal reactions. Additionally, because the three-stage model is uncommon, parameters must be re-determined for batteries with different degrees of aging |

| SOH model [31] | This model uses internal reactions to simulate thermal runaway in batteries with varying State of Health (SOH) | It requires experimentally measuring parameters for each specific aging state |

| SEI growth model [32] | This model uses internal reactions based on aging mechanisms to simulate thermal runaway in aged batteries, showing innovative potential | Its poorer performance for severely aged batteries (SOH < 80%) |

| Mechanism | Equation | No. |

|---|---|---|

| SEI Decomposition | (2) | |

| (3) | ||

| Negative Electrode Reaction | (4) | |

| (5) | ||

| Positive Electrode Reaction | (6) | |

| (7) | ||

| Electrolyte Decomposition | (8) | |

| (9) | ||

| Aging Reaction | (10) | |

| (11) | ||

| (12) |

| Parameter | Description | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEI decomposition activation energy | 1.38 × 105 | J/mol | |

| Negative-solvent activation energy | 1.32 × 105 | J/mol | |

| Positive-solvent activation energy | 0.99 × 105 | J/mol | |

| Electrolyte decomposition activation energy | 2.70 × 105 | J/mol | |

| SEI decomposition frequency factor | 1.66 × 1015 | 1/s | |

| Negative-solvent frequency factor | 2.50 × 1013 | 1/s | |

| Positive-solvent frequency factor | 2.00 × 108 | 1/s | |

| Electrolyte decomposition frequency factor | 5.14 × 1025 | 1/s | |

| Reaction order for SEI decomposition | 1 | / | |

| Reaction order for electrolyte decomposition | 1 | / | |

| SEI decomposition heat release | 2.57 × 105 | J/kg | |

| Negative-solvent heat release | 1.714 × 105 | J/kg | |

| Positive-solvent heat release | 1.947 × 105 | J/kg | |

| Electrolyte decomposition heat release | 6.20 × 105 | J/kg | |

| Specific negative active content | 220 | kg/m3 | |

| Specific positive active content | 520.74 | kg/m3 | |

| Specific electrolyte content | 334.68 | kg/m3 | |

| Initial value | 0.15 | / | |

| Initial value | 0.75 | / | |

| Initial value | 1 | / | |

| The molar mass of the film | 0.162 | kg/mol | |

| The molar density of the film | 1690 | kg/m3 | |

| The volume fraction of carbon | 0.58 | / | |

| The negative electrode thickness | 3.45 × 10−5 | m | |

| The thickness of the SEI layer | 5 × 10−9 | m | |

| A | The geometric area of the negative electrode | 0.18 | m2 |

| The graphite particle modeling the negative electrode | 5 × 10−6 | m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Mei, Y.; Lu, K. Influence of Aging on Thermal Runaway Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Experiments and Simulations for Engineering Education. Fire 2025, 8, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120479

Wang J, Chen Y, Mei Y, Lu K. Influence of Aging on Thermal Runaway Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Experiments and Simulations for Engineering Education. Fire. 2025; 8(12):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120479

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jie, Yihao Chen, Yufei Mei, and Kaihua Lu. 2025. "Influence of Aging on Thermal Runaway Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Experiments and Simulations for Engineering Education" Fire 8, no. 12: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120479

APA StyleWang, J., Chen, Y., Mei, Y., & Lu, K. (2025). Influence of Aging on Thermal Runaway Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Experiments and Simulations for Engineering Education. Fire, 8(12), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120479