A Numerical Study on the Smoke Diffusion Characteristics in Tunnel Fires During Construction Under Pressed-In Ventilation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

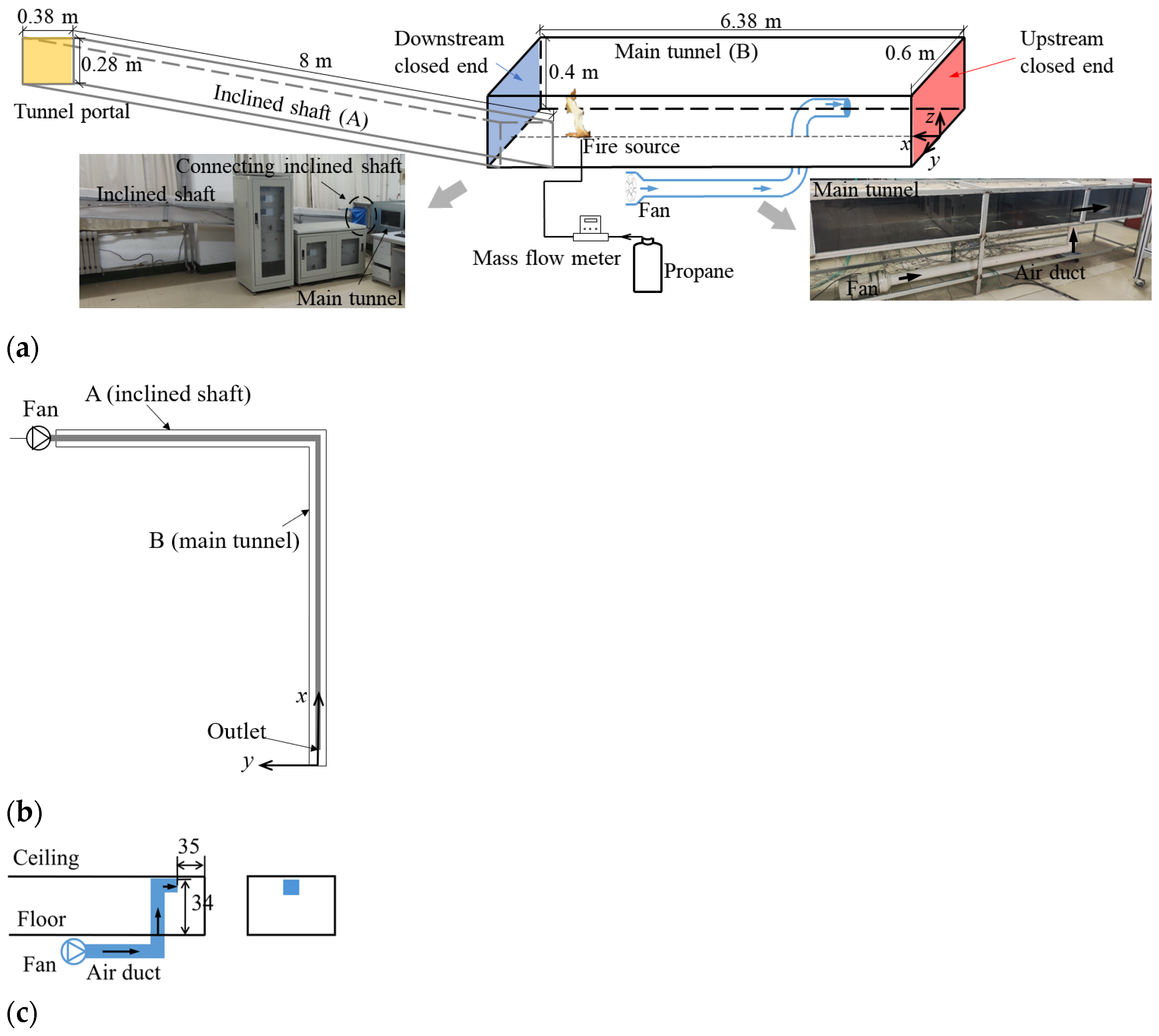

2.1. Reduced-Scale Experiment

2.1.1. Experimental Bench Setup

- (1)

- In pressed-in ventilation, PVC air ducts are usually adopted as the air supply channels;

- (2)

- The flash point of PVC material is approximately 240 °C to 270 °C. PVC air ducts have good fire resistance and are not easily burned directly;

- (3)

- When the air duct has not failed, the influence of the airflow generated by the forced ventilation on the diffusion of flue gas becomes the main factor, which is precisely the focus of this study.

2.1.2. Feasibility Analysis

2.2. Numerical Simulation

2.2.1. Fire Dynamics Simulator

2.2.2. Physical Model Setup

2.2.3. Fire Scenarios Settings

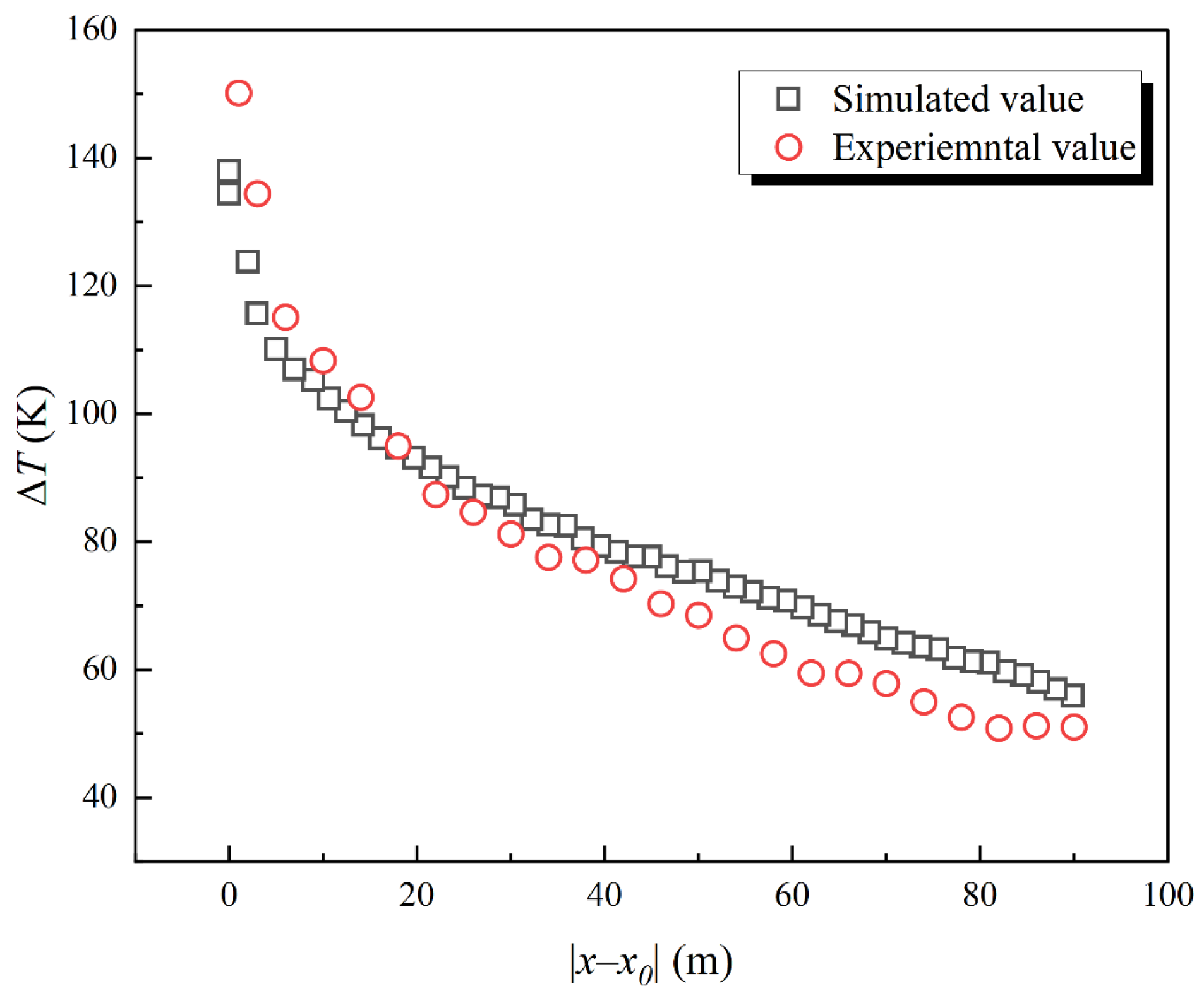

2.2.4. Analysis of Grid Sensitivity and Model Verification

3. Results and Discussion

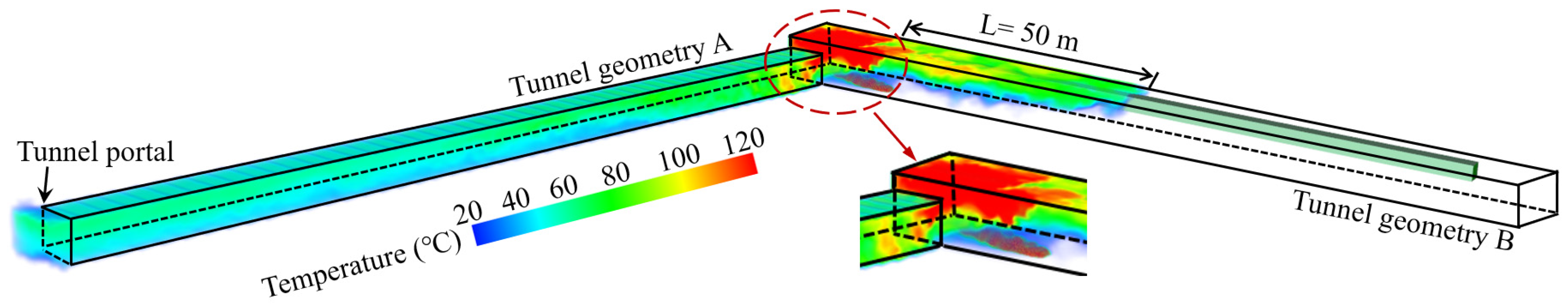

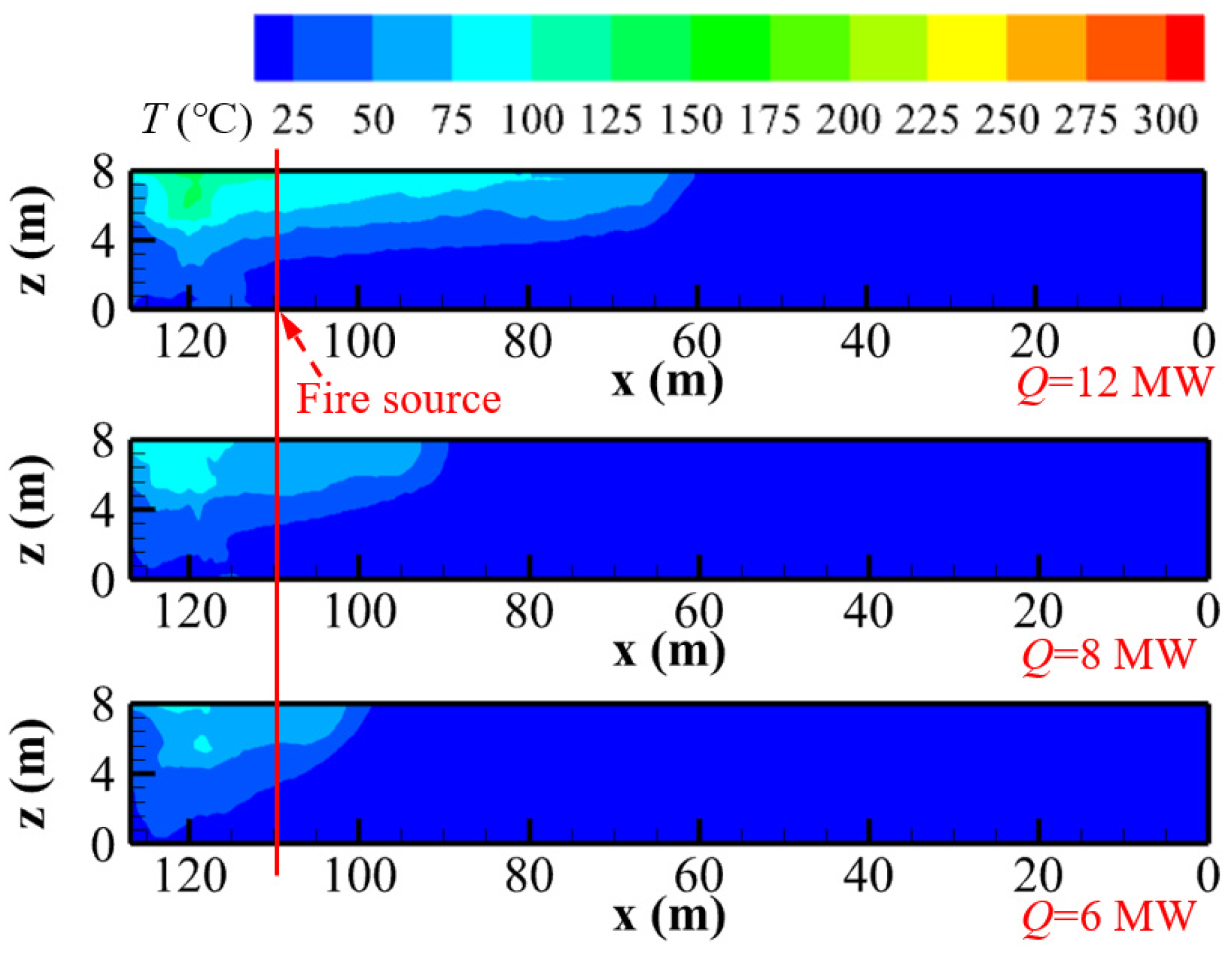

3.1. Smoke Diffusion Characteristics

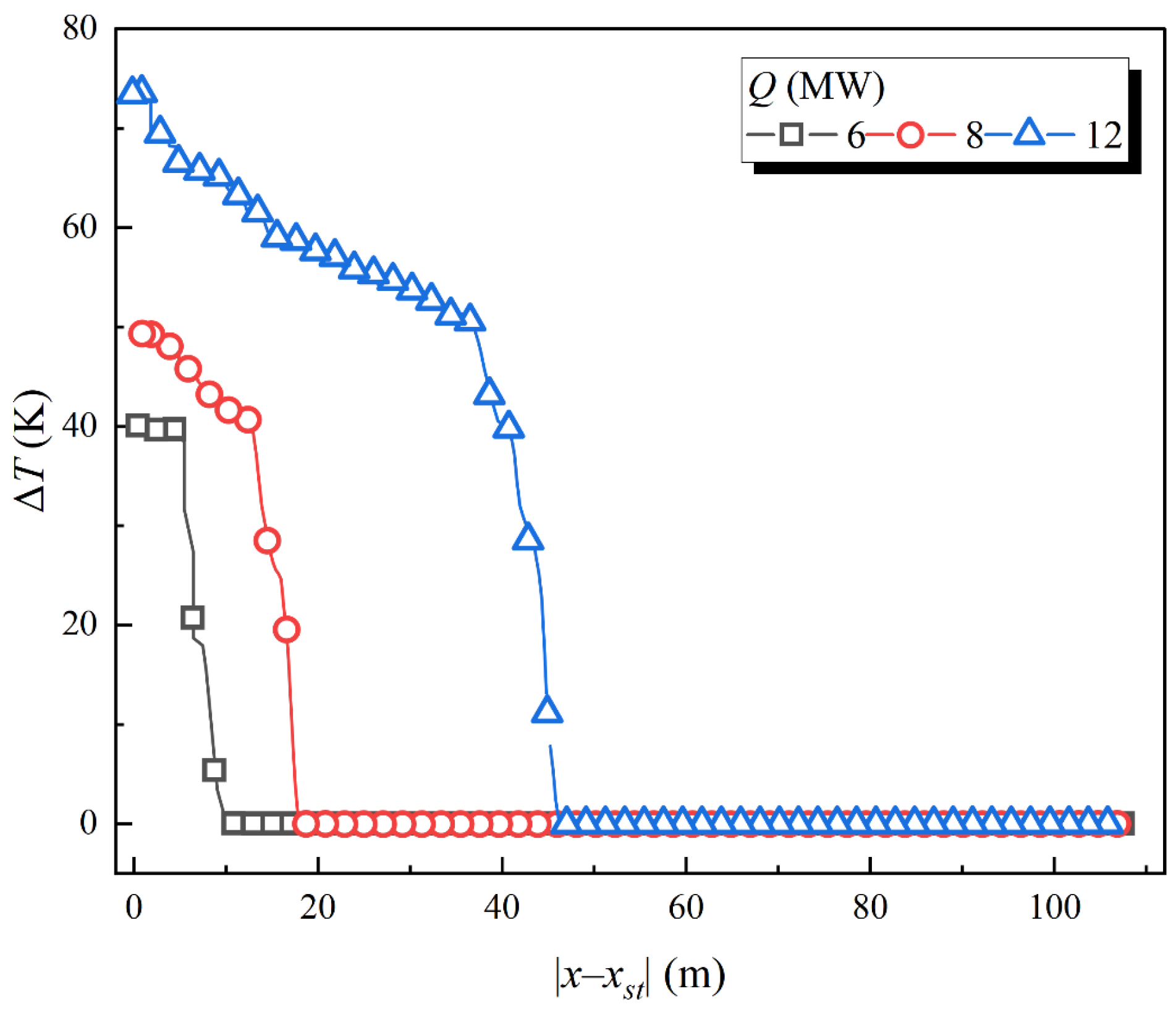

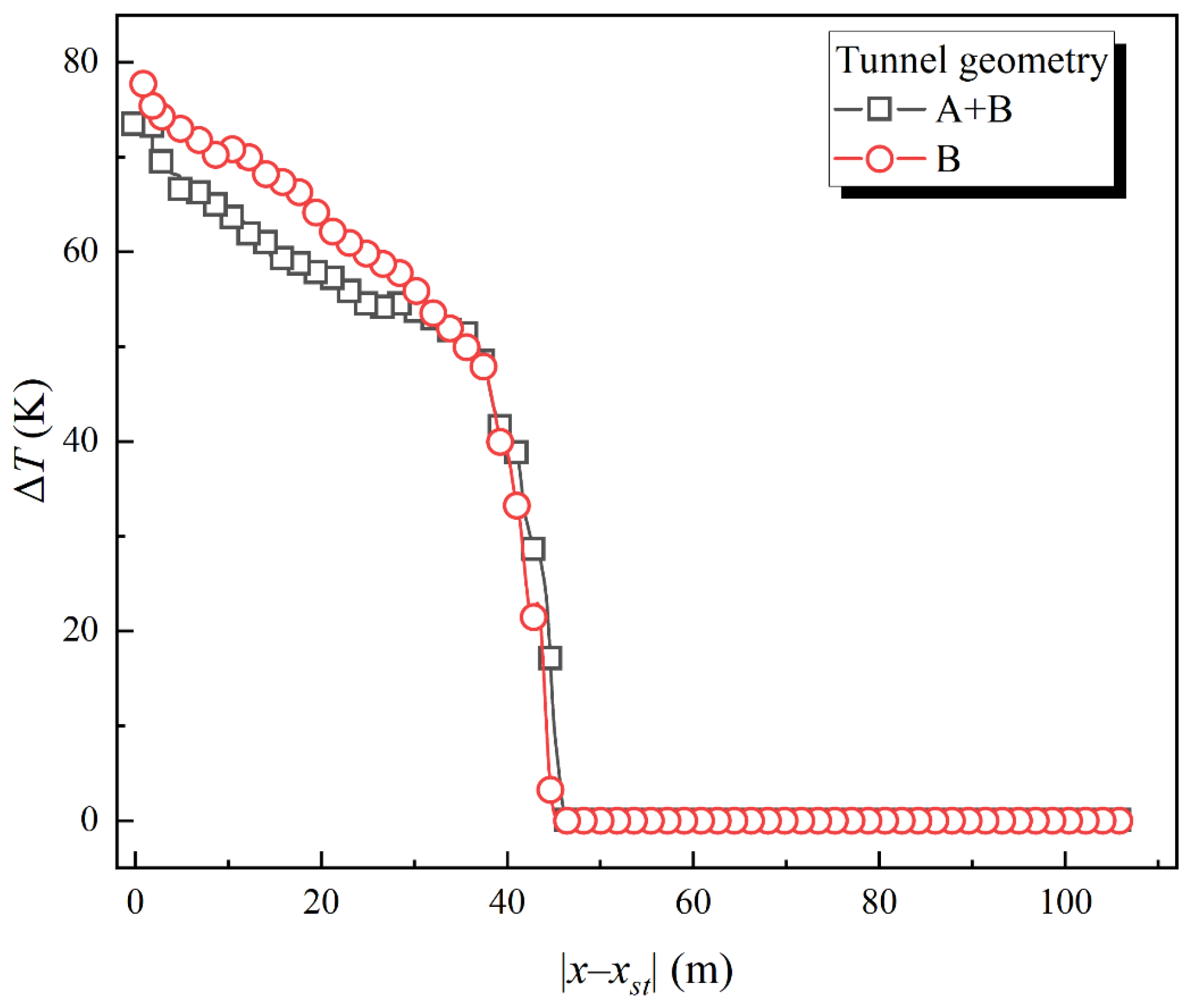

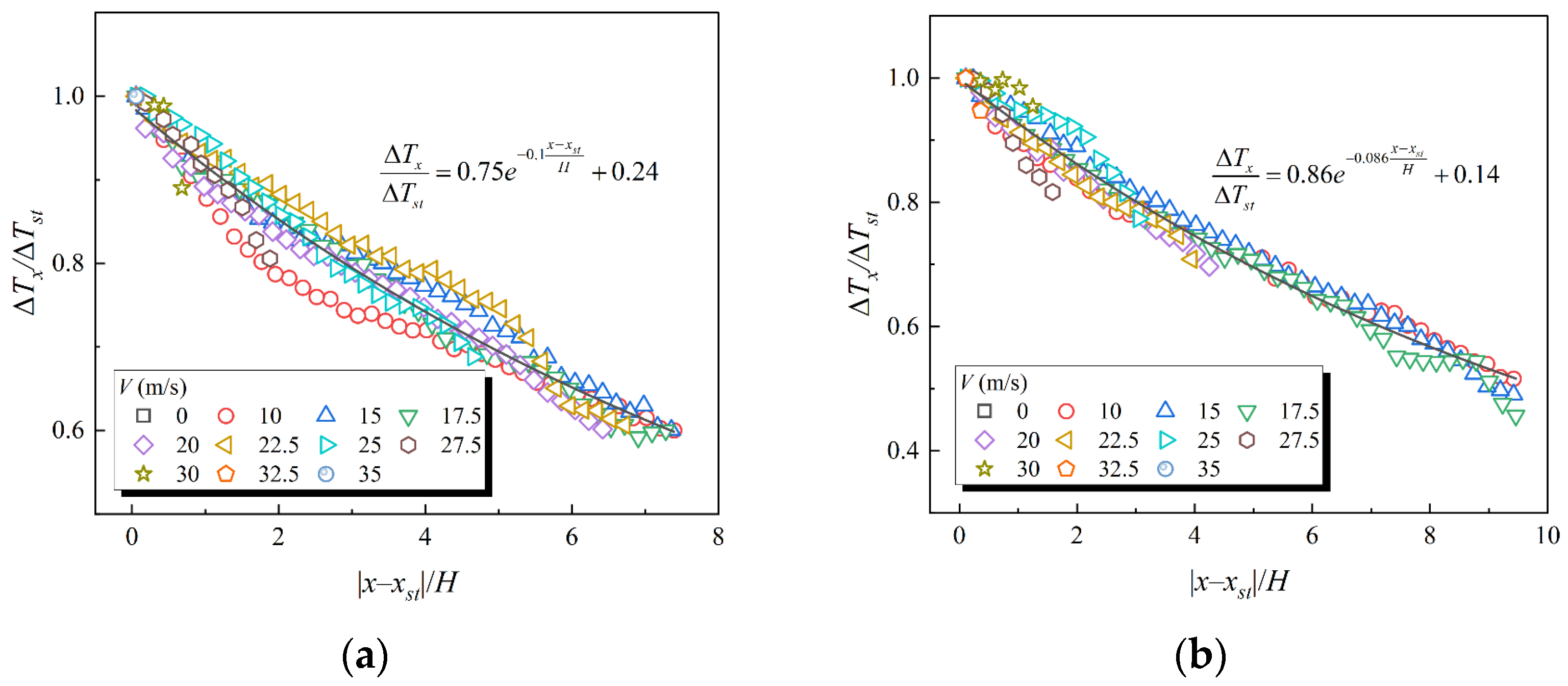

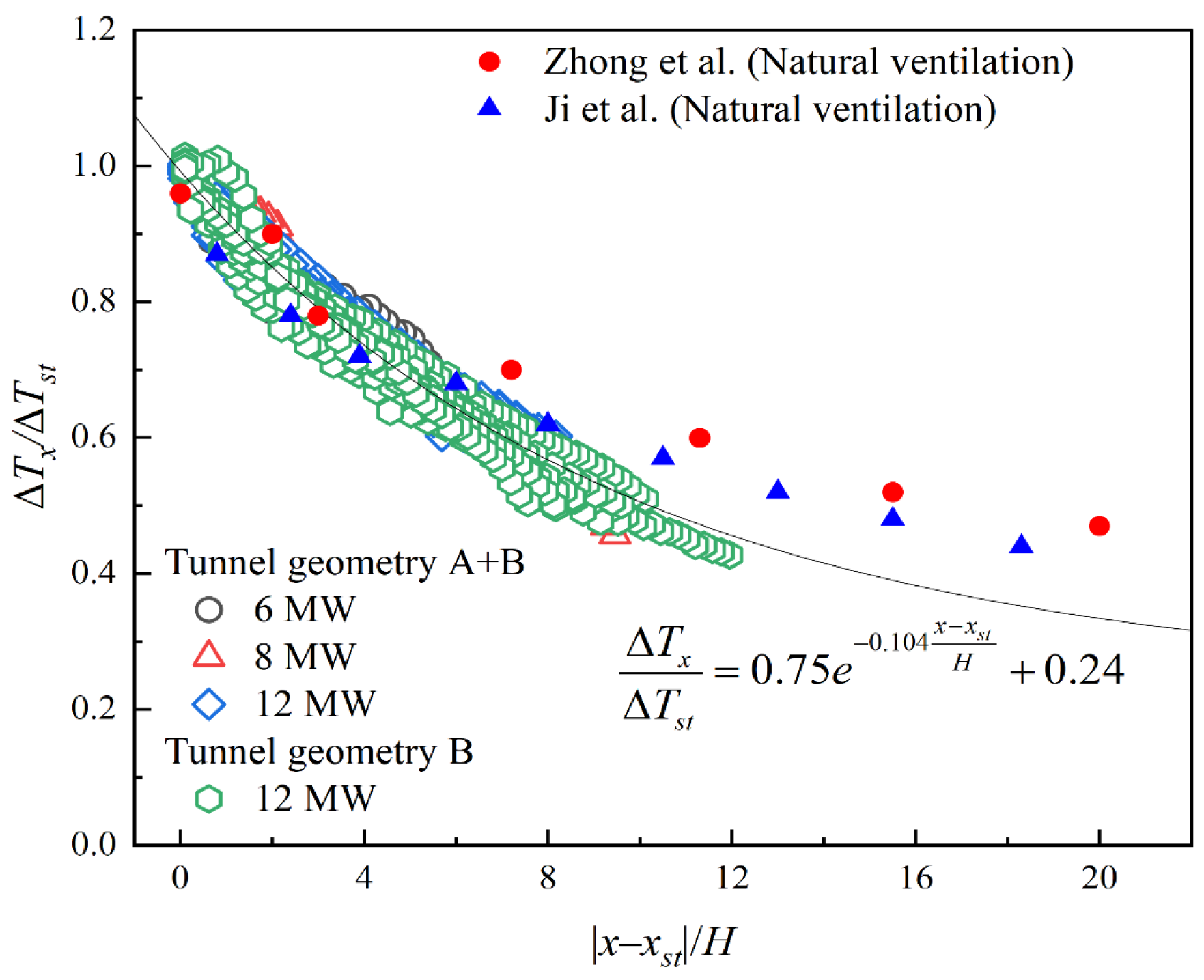

3.2. Longitudinal Temperature Decay of the Ceiling

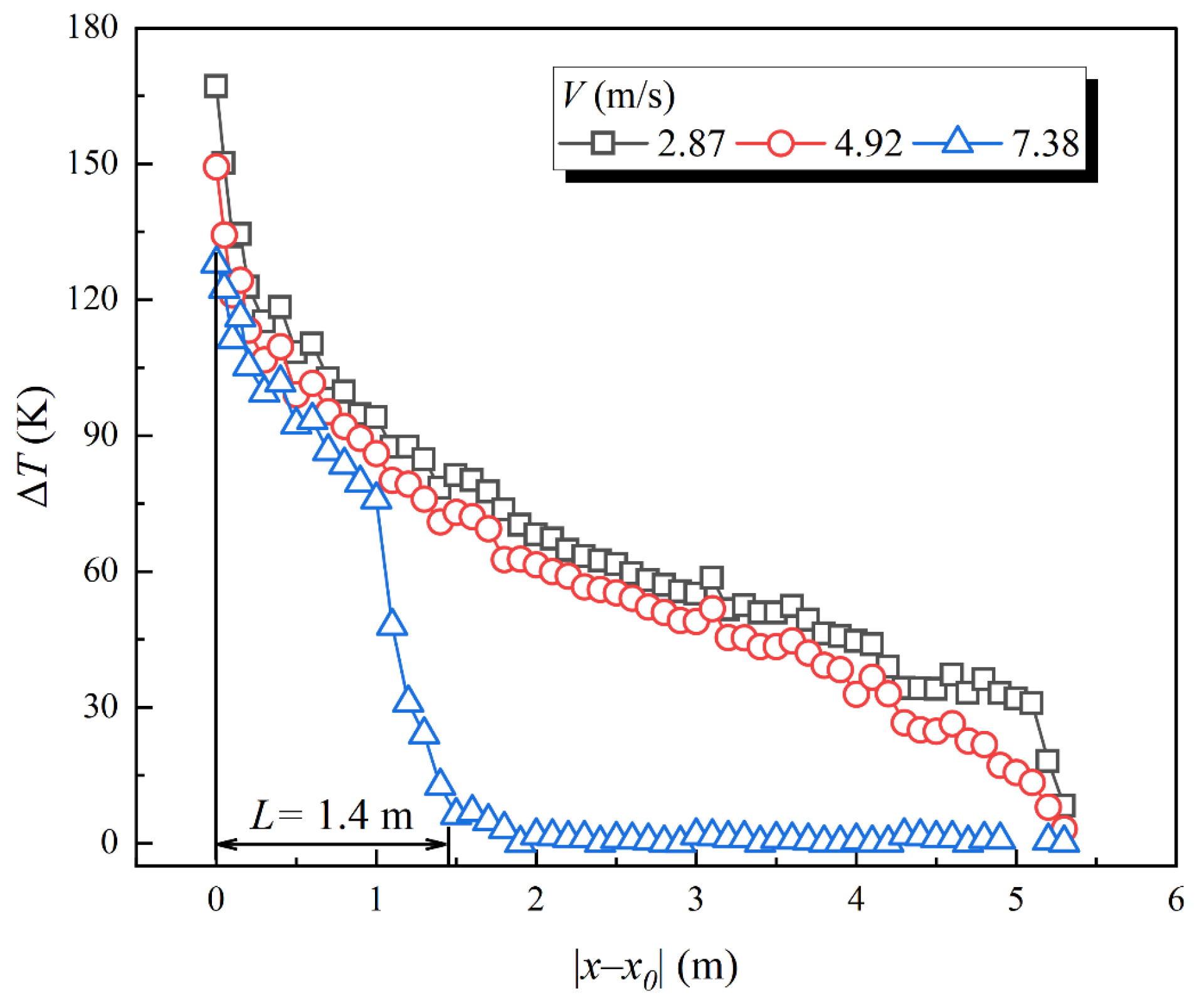

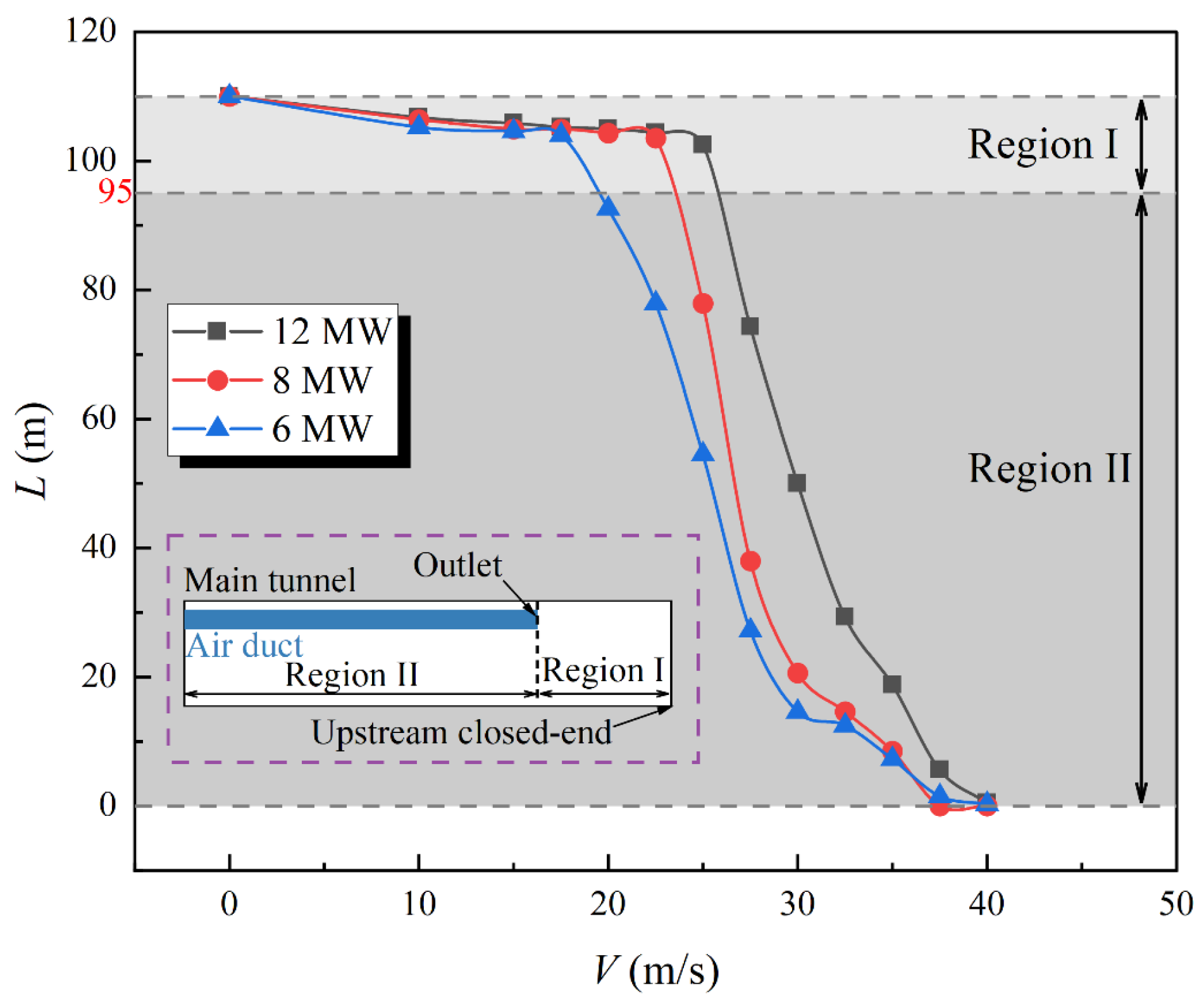

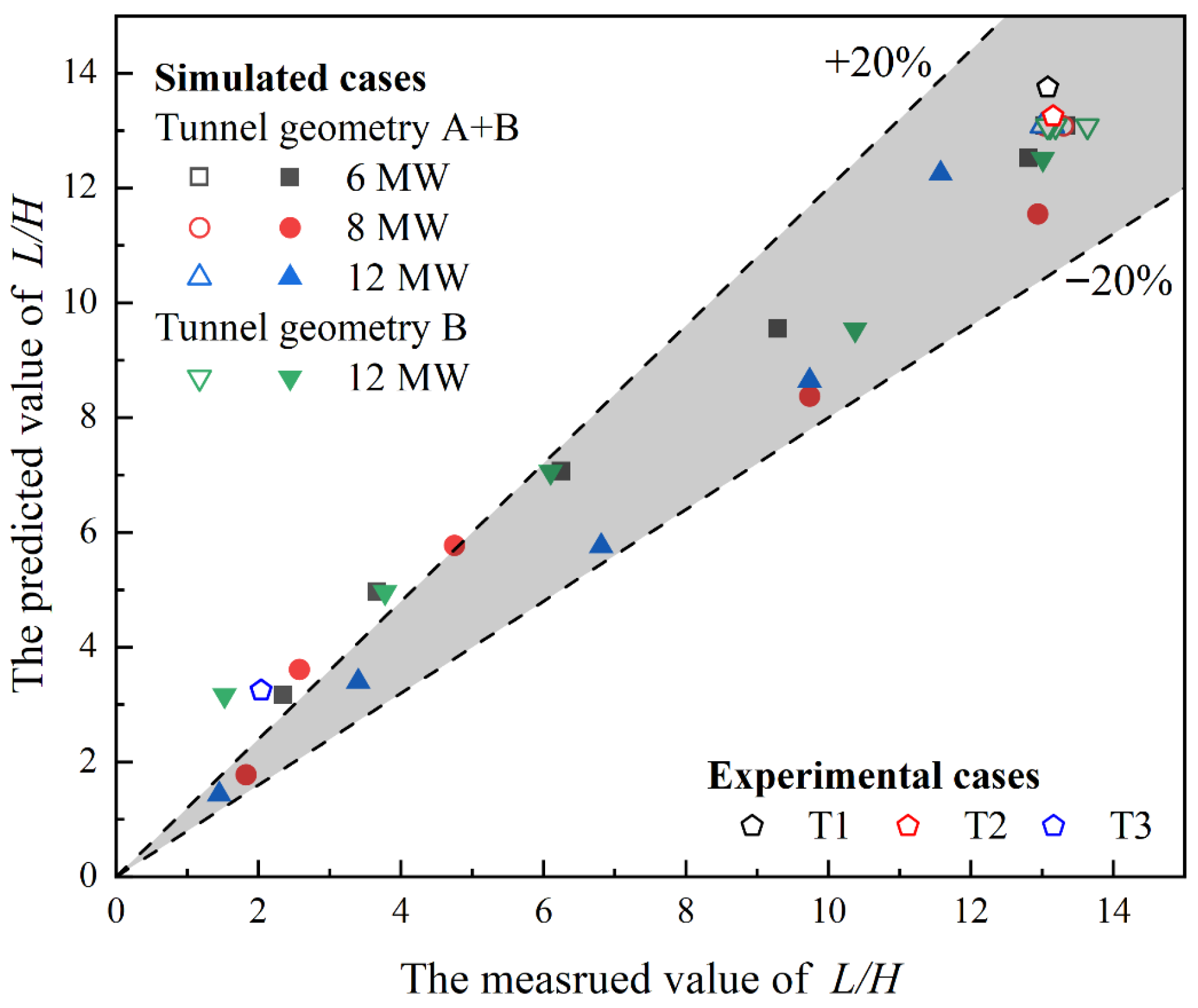

3.3. Smoke Back-Layering Length

3.4. Limitations

- (1)

- The location of the fire source was not taken into account;

- (2)

- The slope of the inclined shaft was not taken into account;

- (3)

- A relatively short length of the main tunnel was selected.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the reduced-scale experimental study, it was found that the smoke has a back-layering flow phenomenon when V = 7.38 m/s, with a back-layering length of 1.4 m. This initially verified the feasibility of the fire smoke control in the tunnel during construction under the pressed-in ventilation.

- (2)

- Due to the pressed-in ventilation, the smoke back-layering flow phenomenon occurs in Tunnel Geometry B. In this condition, the smoke layer is destroyed and declines close to the floor, and the smoke in Tunnel Geometry A spreads throughout the cross-section and is exhausted out of the tunnel. As the value of V increases and the HRR decreases, both the longitudinal temperature of smoke on the ceiling and the SBL in Tunnel Geometry B are reduced. When Q = 12 MW and V = 40 m/s (Tunnel Geometry A + B), the smoke back-layering flow phenomenon has disappeared. There is no longer any smoke remaining between the fire source and the upstream closed end.

- (3)

- The dimensionless predictive models for the longitudinal temperature decay of the ceiling and the SBL were obtained through the combination of theoretical analysis and numerical simulation. Compared with previous studies, when |x − xst|/H > 10.4, the increased convective heat transfer between the smoke and airflow due to ventilation leads to a relatively low predicted value of ΔTx/ΔTst from the predictive model. When the smoke front is close to the fire source, the predicted value of the smoke’s back-layering length is relatively high due to the influence of thermal radiation. The error caused by this assumption did not affect the overall accuracy of the result, and the error range is still within an acceptable range. Meanwhile, the results of the simulation predictive model are close to the experimental values. The predictive model remains accurate and reliable.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoon, Y.-E.; Bae, Y.-H.; Seung-Chul, L. Fire Risk Assessment in railway tunnels based on human safety assessment criteria in Korea. Fire Saf. J. 2025, 157, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingason, H. Model scale tunnel tests with water spray. Fire Saf. J. 2008, 43, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.S.; Lantsoght, E.; Hendriks, M.A.N. Structural behaviour of tunnels exposed to fire using numerical modelling strategies. Fire Saf. J. 2025, 152, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Huang, M. Statistical analysis of major tunnel construction accidents in China from 2010 to 2020. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 124, 104460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Cao, B.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L. Estimating the longitudinal maximum gas temperature attenuation of ceiling jet flows generated by strong fire plumes in an urban utility tunnel. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 142, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Qiu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, C.; Yu, W.; Zhao, S.; Li, L.; Liu, J. Experimental study on vertical temperature distribution of the two-layer smoke flow in tunnel during construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 136, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.Z.; Wang, R.; Xia, Z.Y.; Ren, F.; Zhao, J.L.; Zhu, H.Q.; Cheng, X.D. Numerical study of the characteristics of smoke spread in tunnel fires during construction and method for improvement of smoke control. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.K.; Chai, J.R.; Luo, J.P.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Z.G.; Cao, J. Tunnel ventilation during construction and diffusion of hazardous gases studied by numerical simulations. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Bu, R.W.; Ma, F.; Shen, Y.J. Effect of press-in ventilation technology on pollutant transport in a railway tunnel under construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Tan, T.; Gao, Z.; Wan, H.; Zhu, J.; Ding, L. Numerical Investigation on the Influence of Length–Width Ratio of Fire Source on the Smoke Movement and Temperature Distribution in Tunnel Fires. Fire Technol. 2019, 55, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Yu, W.; Ding, C.; Yu, K.F.; Zhao, S.Z.; Chen, S.; Li, L.Y. Theoretical prediction on supply air performance and CO dilution effect of the pressed-in ventilation system during the construction period. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 157, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K. A Computational Flow Analysis for Choosing the Diameter and Position of an Air Duct in a Working Face. J. Min. Sci. 2011, 47, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.E.; Forouhandeh, S.F. Reliability estimation of auxiliary ventilation systems in long tunnels during construction. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, J.; Sanabria, M.; Fernández-Oro, J.M.; Galdo-Vega, M.; de Prado, L.A.; Bernardo-Sánchez, A. Energy consumption and dilution of toxic gases in underground infrastructures: A case study in a railway tunnel under forced ventilation. Energy 2024, 307, 132810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnermark, A.; Hugosson, J.; Ingason, H. Fire incidents during construction work of tunnels-Model scale experiments. Fire Technol. 2010, 2020, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, S.; Yamauchi, Y. Numerical study of the influence of tunnel wall properties on ceiling jet temperature in tunnel fires. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 116, 104087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Lei, B.; Ingason, H. The maximum temperature of buoyancy-driven smoke flow beneath the ceiling in tunnel fires. Fire Saf. J. 2011, 46, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Ingason, H. The maximum ceiling gas temperature in a large tunnel fire. Fire Saf. J. 2012, 48, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurioka, H.; Oka, Y.; Satoh, H.; Sugawa, O. Fire properties in near field of square fire source with longitudinal ventilation in tunnels. Fire Saf. J. 2003, 38, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.H.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.F.; Yi, L. A non-dimensional global correlation of maximum gas temperature beneath ceiling with different blockage–fire distance in a longitudinal ventilated tunnel. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 56, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, R.L. Calculation of response time of ceiling-mounted fire detectors. Fire Technol. 1972, 8, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, H.; Shi, L. Maximum smoke temperature beneath the ceiling in an enclosed channel with different fire locations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 111, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Lei, B.; Ingason, H. Study of critical velocity and backlayering length in longitudinally ventilated tunnel fires. Fire Saf. J. 2010, 45, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, N. Experimental study on flame merging behaviors and smoke backlayering length of two fires in a longitudinally ventilated tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 137, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.B.; Liu, X.; Dong, B.Y.; Zhong, H.; Wang, B.; Dong, Q.W. Effect of inclined mainline on smoke backlayering length in a naturally branched tunnel fire. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 134, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Wei, R.; Wang, J. Understanding sidewall constraint involving ventilation effects on temperature distribution of fire-induced thermal flow under a tunnel ceiling. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 129, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, Z.; Lei, Z.; Xie, B.; Liu, Q. Study of air supplement velocity by thermal stack effect and critical velocity under longitudinal ventilation in the uniclinal V-shaped tunnel. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 60, 104723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, M.S.; Khurana, S.; Chowdhury, S. A numerical method for studying the effect of calcium silicate lining on road tunnel fires. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 29, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, P.; Chen, C.; Wu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Liu, X. A Study on the Influence of Mobile Fans on the Smoke Spreading Characteristics of Tunnel Fires. Fire 2024, 7, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Coedo, D.; Ayala, P.; Cantizano, A.; Węgrzyński, W. A coupled hybrid numerical study of tunnel longitudinal ventilation under fire conditions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 36, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingason, H.; Lönnermark, A.; Frantzich, H.; Kumm, M. Fire Incidents During Construction Work of Tunnels; SP Sveriges Tekniska Forskningsinstitut: Borås, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- JTG/T 3660—2020; Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Tunnel. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- McGrattan, K.; Hostikka, S.; McDermott, R.; Floyd, J.; Weinschenk, C.; Overholt, K. Fire Dynamics Simulator User’s Guide; NIST Special Publication; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2013; Volume 1019, p. 6.

- Tong, W.; Ge, F.; Ding, L.; Ji, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, F. Full-scale experimental and numerical study of smoke spread characteristics in a long-closed channel with one lateral opening. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinling, L.; Miaocheng, W.; Fang, L.; Fei, W.; Jiaqiang, H.; Sherman, C.C. Effect of bifurcation angle and fire location on smoke temperature profile in longitudinal ventilated bifurcated tunnel fires. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2022, 127, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Fan, C.G.; Zhong, W.; Shen, X.B.; Sun, J.H. Experimental investigation on influence of different transverse fire locations on maximum smoke temperature under the tunnel ceiling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 4817–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Shi, C.; He, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, C.; Tian, X. Smoke development in full-scale sloped long and large curved tunnel fires under natural ventilation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 108, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Luo, X.; Zeng, F. Study on CO diffusion law and concentration distribution function under ventilation after blasting in high-altitude tunnel. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 220, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.Z.; Ma, J.M.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, S.L.; Wang, Z.W. Numerical study on the mean velocity distribution law of air backflow and the effective interaction length of airflow in forced ventilated tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 46, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Guo, F.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, J. Effects of ambient pressure on transport characteristics of thermal-driven smoke flow in a tunnel. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 125, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Unit | Scaling |

|---|---|

| Geometry (m) | Lmodel/Lfull |

| HRR (kW) | Qmodel/Qfull = (Lmodel/Lfull)5/2 |

| Velocity (m/s) | vmodel/vfull = (Lmodel/Lfull)1/2 |

| Time (s) | tmodel/tfull = (Lmodel/Lfull)1/2 |

| Temperature (K) | Tmodel/Tfull = Lmodel/Lfull |

| Case No. | Q [MW] | V [m/s] | Tunnel Geometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 4.47 kW | 2.87 | A + B |

| T2 | 4.92 | ||

| T3 | 7.38 |

| Case No. | Q [MW] | V [m/s] | Tunnel Geometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–13 | 6 | 0/10/15/17.5/20/22.5/25/27.5/30/32.5/35/37.5/40 | A + B |

| 14–26 | 8 | A + B | |

| 27–39 | 12 | A + B | |

| 40–52 | 12 | B |

| xst [m] | |x − xst| [m] | Q [MW] |

|---|---|---|

| 107.45 | 2.55 | 6 |

| 106.87 | 3.13 | 8 |

| 105.82 | 4.18 | 12 |

| Q [MW] | Tunnel Geometry | a | b | c | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | A + B | 0.75 | −0.1 | 0.24 | 0.95 |

| 8 | A + B | 0.86 | −0.086 | 0.14 | 0.97 |

| 12 | A + B | 0.61 | −0.127 | 0.37 | 0.95 |

| 12 | B | 0.79 | −0.103 | 0.21 | 0.97 |

| Tunnel Geometry | Q [MW] | V′ [m/s] |

|---|---|---|

| A + B | 6 | 37.5 |

| A + B | 8 | 37.5 |

| A + B | 12 | 40 |

| B | 12 | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, L.; Qiu, M.; Liu, M. A Numerical Study on the Smoke Diffusion Characteristics in Tunnel Fires During Construction Under Pressed-In Ventilation. Fire 2025, 8, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120480

Li L, Li Y, Wang K, Xu L, Qiu M, Liu M. A Numerical Study on the Smoke Diffusion Characteristics in Tunnel Fires During Construction Under Pressed-In Ventilation. Fire. 2025; 8(12):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120480

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Longyue, Yanfeng Li, Kangyue Wang, Lin Xu, Mingxuan Qiu, and Mengzhen Liu. 2025. "A Numerical Study on the Smoke Diffusion Characteristics in Tunnel Fires During Construction Under Pressed-In Ventilation" Fire 8, no. 12: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120480

APA StyleLi, L., Li, Y., Wang, K., Xu, L., Qiu, M., & Liu, M. (2025). A Numerical Study on the Smoke Diffusion Characteristics in Tunnel Fires During Construction Under Pressed-In Ventilation. Fire, 8(12), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120480