Quantifying Global Wildfire Regimes and Disparities in Evacuation Efficacy in the Anthropocene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Data

2.2. Research Methods

3. Results

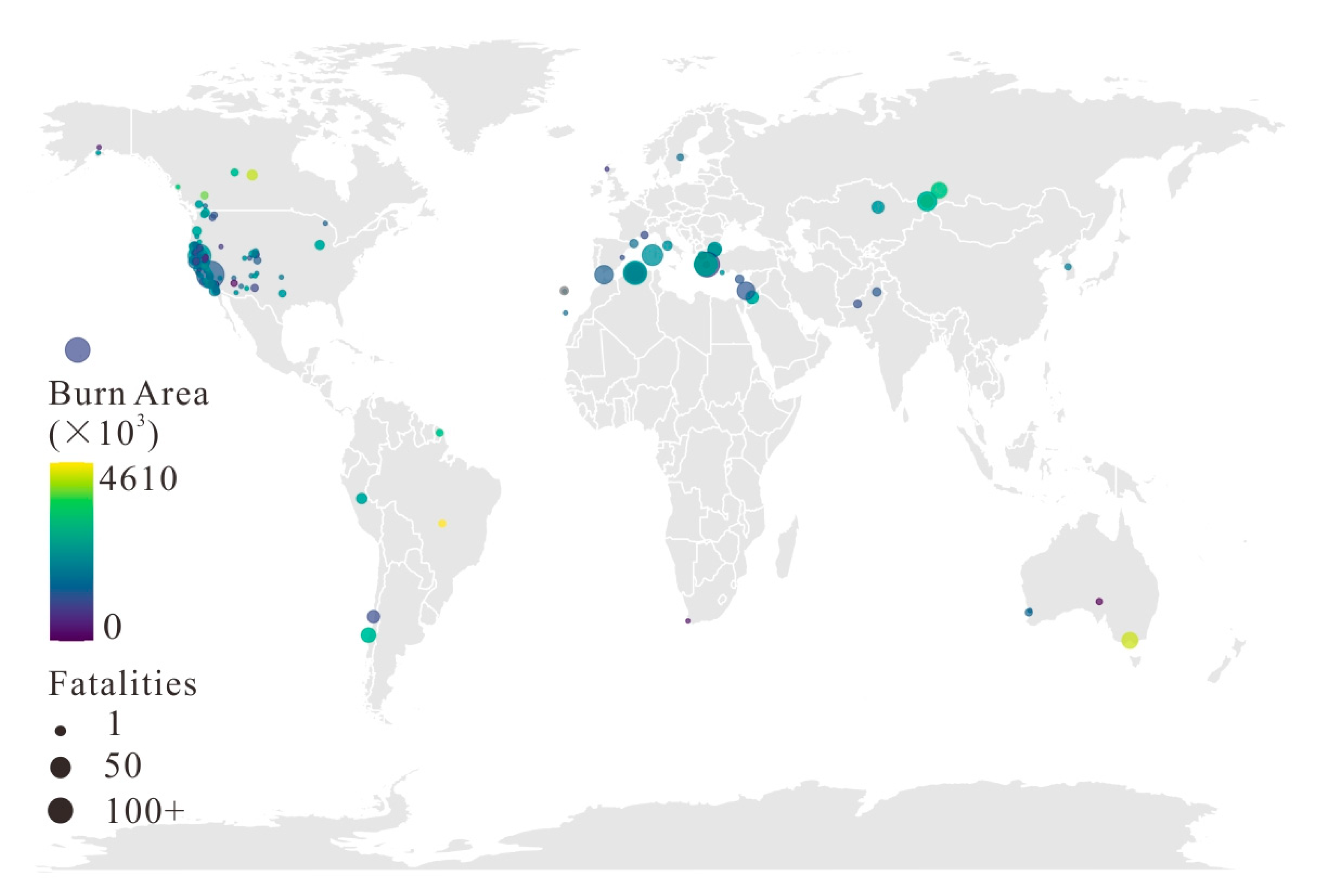

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Basic Characteristics

3.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution Trends

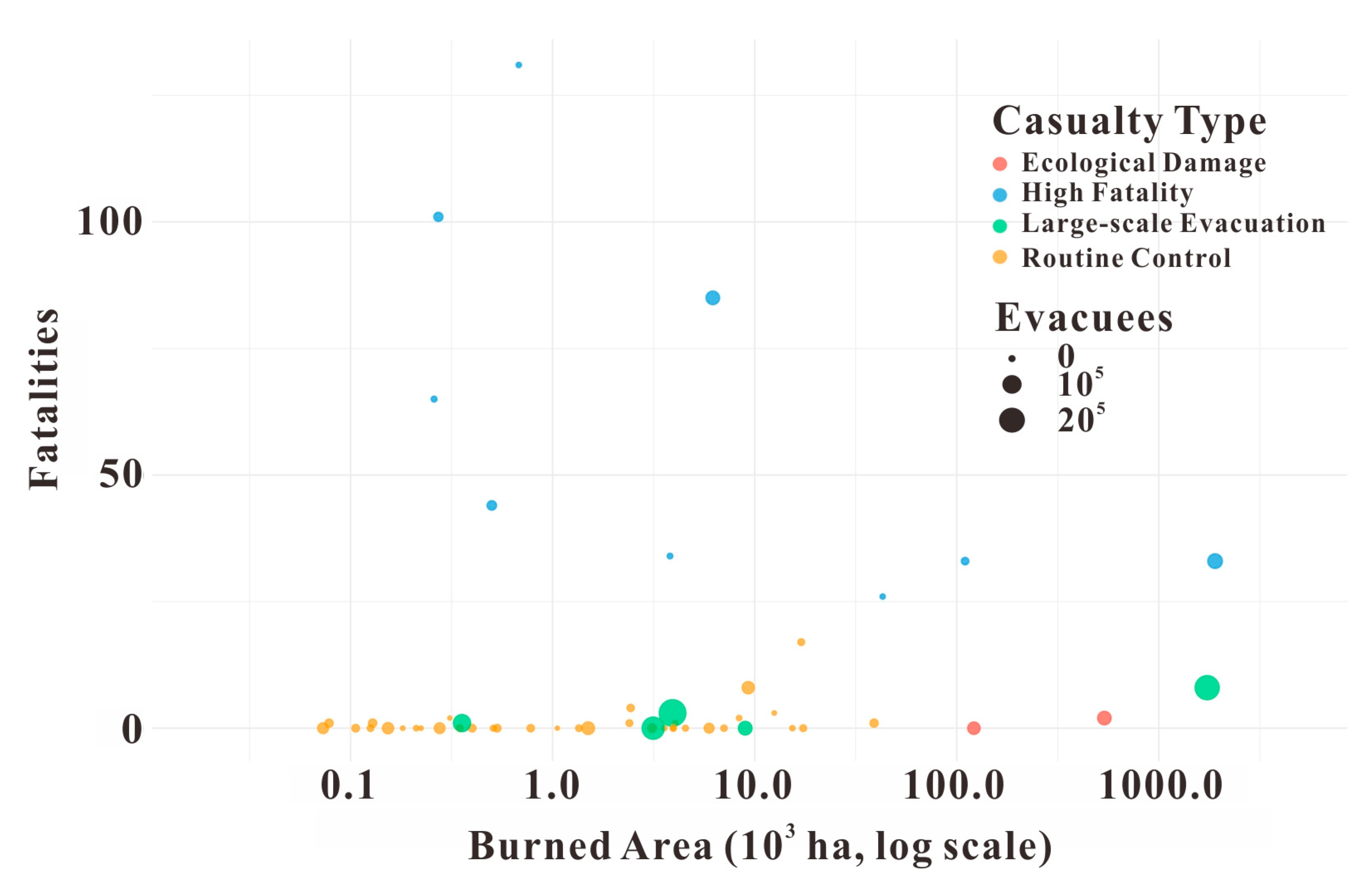

3.3. Identification of Casualty Patterns

3.4. Policy Effectiveness Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Extreme Asymmetry in Wildfire Disaster Characteristics

4.2. Evolving Spatiotemporal Patterns in Global Wildfire Regimes

4.3. Policy Implications of Identified Casualty Patterns

4.4. National Disparities in Evacuation Efficiency

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Our analysis of the 2018–2024 event sample provides evidence of significant ‘extremization’ and ‘polarization’ characteristics in global wildfire risk. Descriptive statistical results indicate that the distributions of burned area, casualties, and evacuation scale all exhibit strong right-skewness, meaning a minority of catastrophic events dominate the overall losses. These near-term patterns suggest that wildfire risk management should increasingly shift from addressing “normal” events to highly prioritizing the prevention and preparedness for “catastrophic” scenarios.

- The spatiotemporal patterns of wildfires are undergoing structural transformation. Temporally, the frequency and impact severity of major events show a fluctuating upward trend within the studied period. Spatially, the risk pattern is expanding from traditional hotspots in North America and Australia to emerging regions including Mediterranean Europe, Chile, and the Russian Far East, suggesting that wildfire risk may be breaking through traditional geographical and climatic boundaries. The three major spatiotemporal cluster patterns identified provide a scientific roadmap for implementing proactive, seasonal global resource allocation.

- The study innovatively identifies four distinct casualty patterns: “High-Lethality”, “Large-Scale Evacuation”, “Routine-Control”, and “Ecological-Destruction”. This typological framework indicates that the human impacts of wildfires result from the combined effects of hazard intensity, social exposure, and emergency management capacity. It reveals that successful risk management does not solely pursue fire suppression but requires precise strategic trade-offs between pre-disaster prevention (e.g., regulated land use), disaster response (e.g., efficient evacuation), and post-disaster recovery (e.g., ecological restoration) according to specific contexts.

- Based on the 2018–2024 sample, national development level suggests a strong association with emergency response efficacy. The vast 65-fold disparity in evacuation efficiency between developed and developing countries highlights a substantial “development chasm” in emergency management capabilities. This finding emphasizes that enhancing global wildfire resilience is not merely a technical issue but fundamentally a developmental challenge, urgently requiring the international community to address systemic shortcomings through technology transfer, capacity building, and financial support.

- Building on the findings and limitations of this study, we propose the following directions for future research: Future studies should integrate high-resolution satellite data with localized socioeconomic, governance, and infrastructural indicators to better isolate the causal mechanisms underlying the observed disparities in evacuation efficiency and casualty patterns. Develop and validate dynamic evacuation models that incorporate real-time data on risk perception, communication flows, and population mobility to improve the predictive capacity and practical utility of evacuation efficiency metrics. Long-Term Ecological and Health Impacts: Conduct longitudinal studies to quantify the long-term ecological consequences (e.g., biodiversity loss, carbon cycle disruption) and public health impacts of the “Ecological-Destruction” pattern, which are currently underrepresented in disaster assessment frameworks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11770–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; van der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Grafton, R.Q. Socioeconomic well-being losses of Australia’s Black Summer fires (2019–2020): Burden by burned area, poverty, and gender. One Earth 2025, 8, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, M.; Swain, D.L.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Sarhadi, A.; Kolden, C.A.; Williams, A.P.; Diffenbaugh, N.S. Climate change is increasing the likelihood of extreme autumn wildfire conditions across California. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeier-Young, M.C.; Gillett, N.P.; Zwiers, F.W.; Cannon, A.J.; Anslow, F.S. Attribution of the influence of human-induced climate change on an extreme fire season. Earth’s Future 2019, 7, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; AghaKouchak, A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Goulden, M.L.; Smith, S.L.; Randerson, J.T.; Hall, A.G. Compounding effects of climate change and WUI expansion quadruple the likelihood of extreme-impact wildfires in California. npj Nat. Hazards 2025, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, M.; Rosa-Cánovas, J.J.; Bedia, J.; Jerez, S.; Montávez, J.P.; Llasat, M.C.; Provenzale, A. Exacerbated fires in Mediterranean Europe due to anthropogenic warming projected with non-stationary climate-fire models. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Saura, J.M.; Bacciu, V.; Sirca, C.; Spano, D.; Trabucco, A.; Martínez, J.M.B. The growing link between heatwaves and megafires: Evidence from southern Mediterranean countries of Europe. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 17731–17742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modaresi Rad, A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Kreitler, J.; Alizadeh, M.R.; AghaKouchak, A.; Hudyma, N.; Nauslar, N.J.; Sadegh, M. Human and infrastructure exposure to large wildfires in the United States. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; McDermott, S. The Local Labor Market Impacts of US Megafires. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritzo, L.A. Perspective article: Mitigating social and economic impact of wildfires. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 20, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D.A.; Macdonald, K.J.; Gibson, R.K.; Beaton, N.; Dique, H.; Hradsky, B.A.; Kelly, E.; MacHunter, J.; Pascal, L.; Ritchie, E.G.; et al. Biodiversity impacts of the 2019–2020 Australian megafires. Nature 2024, 635, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Arneth, A.; Forkel, M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gumpenberger, M.; Lasslop, G.; Li, F.; Maignan, F.; et al. Global rise in forest fire emissions linked to climate change in the extratropics. Science 2024, 386, eadl5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raquel, N.A. The state of wildfire and health research: Emerging trends, challenges and gaps. Int. Health 2025, 17, 922–933. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Ye, T.; Yue, X.; Zeng, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, P.; et al. Global population exposure to landscape fire air pollution from 2000 to 2019. Nature 2023, 621, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, M.A.; Batllori, E.; Bradstock, R.A.; Gill, A.M.; Handmer, J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Leonard, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Odion, D.C.; Schoennagel, T.; et al. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature 2014, 515, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andela, N.; Morton, D.C.; Giglio, L.; Chen, Y.; van der Werf, G.R.; Kasibhatla, P.S.; DeFries, R.S.; Collatz, G.J.; Hantson, S.; Kloster, S.; et al. A human-driven decline in global burned area. Science 2017, 356, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doerr, S.H.; Santín, C. Global trends in wildfire and its impacts: Perceptions versus realities in a changing world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D.E.; Cohen, J.D.; Finney, M.A.; Thompson, M.P. How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.; Short, K.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Blanchi, R.; Leonard, J.; Opray, M.; Newnham, G.; Beighel, J.; Middelmann, M.H.; Krusel, N.; et al. Wildfires and WUI Fire Fatalities. In Wildfire Hazards, Risks, and Disasters; Shroder, J.F., Paton, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, C.; Prior, T. The art of learning: Wildfire, amenity migration and local environmental knowledge. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Ryan, B.; Bearman, C.; Toh, K.; Eriksen, C.; Thomas, J.; Lacey, J.; Witt, T.; Hughes, L.; Kroeger, T.; et al. Should we leave now? Behavioral factors in evacuation under wildfire threat. Fire Technol. 2019, 55, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, G.R.; Randerson, J.T.; Giglio, L.; van Leeuwen, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Rogers, B.M.; Mu, M.; van Marle, M.J.E.; Morton, D.C.; Collatz, G.J.; et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Below, R.; Wirtz, A.; Guha-Sapir, D. Disaster Category Classification and Peril Terminology for Operational Purposes; Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krylov, A.; McCarty, J.L.; Potapov, P.; Loboda, T.; Tyukavina, A.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C. Remote sensing estimates of stand-replacement fires in Russia, 2002–2011. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.D. Reproducible research in computational science. Science 2011, 334, 1226–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, S.; Lehmann, C.E.; Belcher, C.M.; Bond, W.J.; Bradstock, R.A.; Daniau, A.-L.; Dixon, K.W.; Grover, S.P.; He, T.; Higgins, S.I.; et al. Biological and geophysical feedbacks with fire in the Earth system. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 033003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Notes on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, J.A.; Wong, M.A. Algorithm AS 136: A K-Means Clustering Algorithm. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. C 1979, 28, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, P.A.P. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 1950, 37, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Amraoui, M.; Bouillon, C.; Coughlan, M.R.; Delogu, G.M.; Fernandes, P.M.; Ferreira, C.; McCaffrey, S.; McGee, T.K.; et al. Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.H.; Boer, M.M.; Collins, L.; Resco de Dios, V.; Clarke, H.; Jenkins, M.; Kenny, B.; Bradstock, R.A. Causes and consequences of eastern Australia’s 2019–2020 season of mega-fires. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritzo, R. Global Disparities in Wildfire Mitigation Financing: A Call for Equitable Investment. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2024, 25, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cattau, M.E.; Wessman, C.; Mahood, A.; Balch, J.K. Anthropogenic and lightning-started fires are becoming larger and more frequent over a longer season length in the USA. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsen, M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Lankao, P.R.; Dube, P.; Leemans, R.; Gaffney, O.; Solecki, W.; Goodess, C. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability to Global Environmental Change: Challenges and Pathways for an Action-Oriented Research Agenda for Middle-Income and Low-Income Countries. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, M.; Nguyen, K.H.; Cutter, S.L. Integrated Research on Disaster Risk: A Scientific Review of the Evidence. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 704–707. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-Quality Health Systems in the Sustainable Development Goals Era: Time for a Revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.; Bai, M. Quantifying Global Wildfire Regimes and Disparities in Evacuation Efficacy in the Anthropocene. Fire 2025, 8, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120477

Han J, Bai M. Quantifying Global Wildfire Regimes and Disparities in Evacuation Efficacy in the Anthropocene. Fire. 2025; 8(12):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120477

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Jiaqi, and Maowei Bai. 2025. "Quantifying Global Wildfire Regimes and Disparities in Evacuation Efficacy in the Anthropocene" Fire 8, no. 12: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120477

APA StyleHan, J., & Bai, M. (2025). Quantifying Global Wildfire Regimes and Disparities in Evacuation Efficacy in the Anthropocene. Fire, 8(12), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120477