TCSN-YOLO: A Small-Target Object Detection Method for Fire Smoke

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- We propose a trident fusion (TF) module to integrate deep features, corresponding features, and shallow features to obtain more shallow small target information.

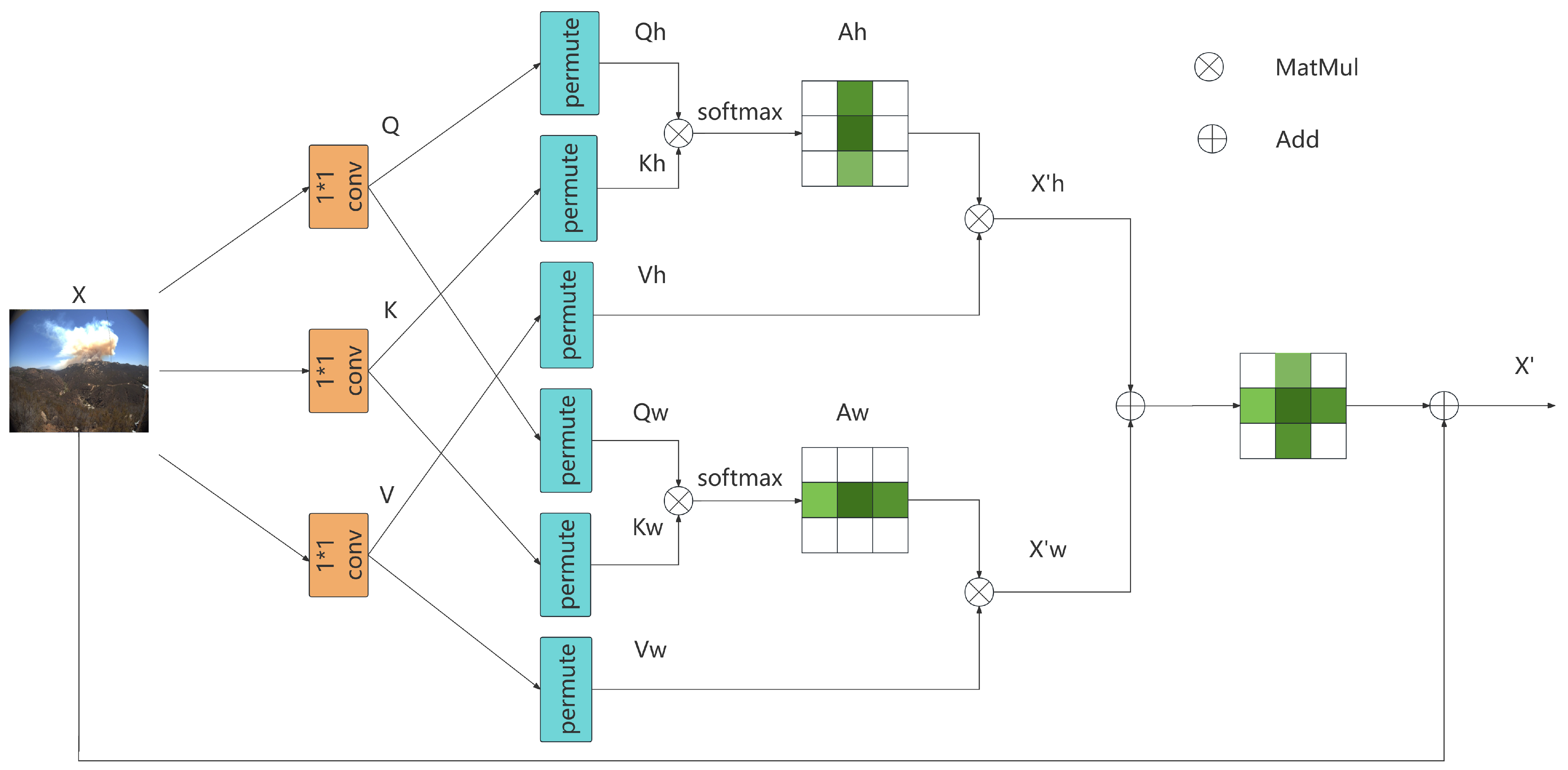

- We propose a Cross Attention Mechanism (CAM) to capture smoke texture features in both horizontal and vertical dimensions.

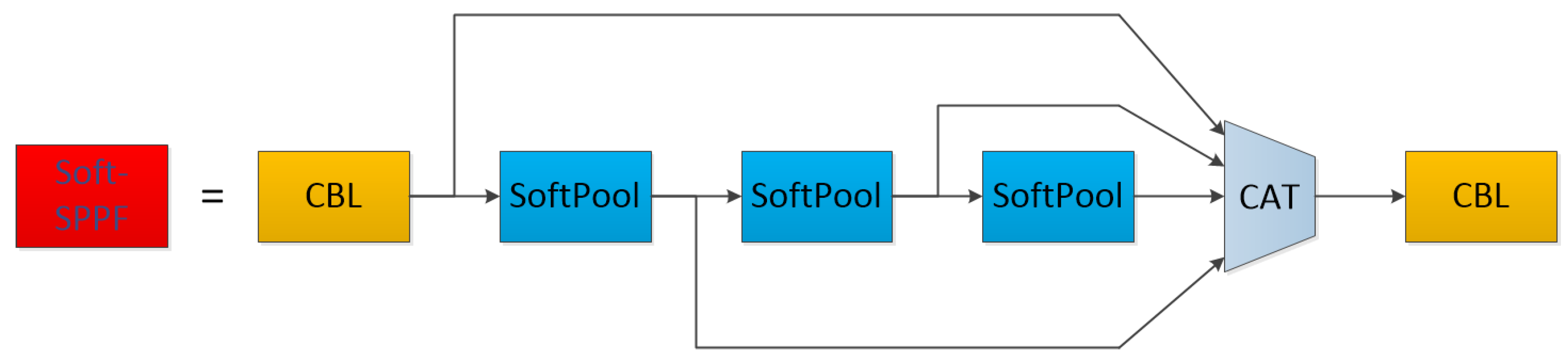

- We replace MaxPool with SoftPool in the SPPF layer of YOLOv8 to minimize information loss during the pooling process while preserving the functionality of the pooling layer.

- Instead of the original CIoU metric, NWD is embedded into the bounding box regression loss function of the detector model.

- The performance of this algorithm was analyzed and compared with other mainstream object detection algorithms.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Trident Fusion

3.2. Cross Attention Module

3.3. Soft-SPPF Module

3.4. Normalized Gaussian Wasserstein Distance Loss

4. Results

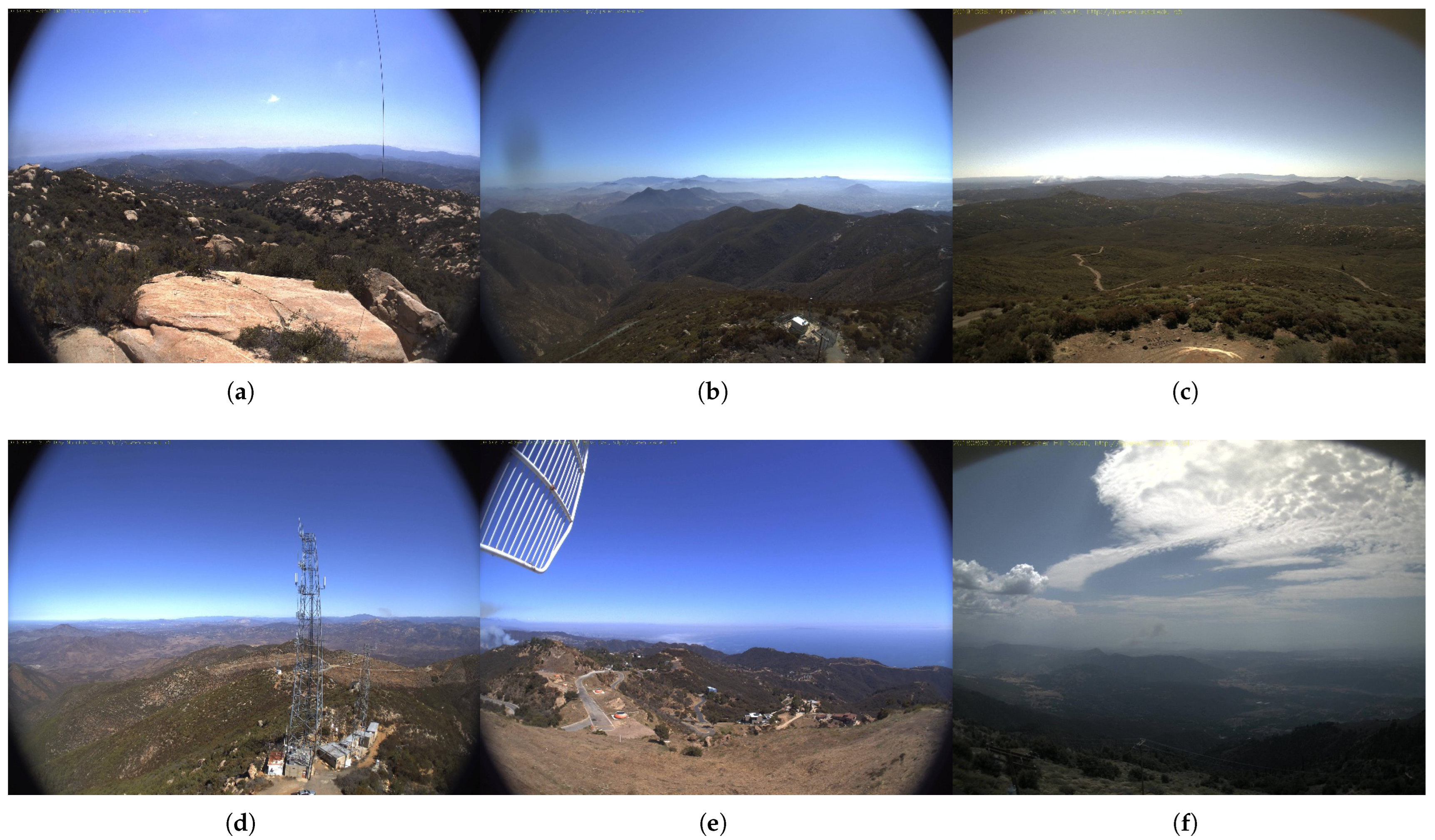

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Experimental Model Evaluation Indicators

- Precision quantifies the proportion of correctly identified positive instances among all samples predicted as positive. The calculation formula is as follows:

- Recall measures the proportion of true positive instances correctly predicted by the model among all actual positive cases. The computational formula is expressed as follows:

- Average Precision.Average Precision (AP) quantifies the model’s precision performance averaged across all recall levels for a specific category, typically computed as the area under the Precision–Recall (PR) curve.

- Params. It quantifies the total parameter count of the model, while it does not directly influence the inference speed, it fundamentally determine memory requirements during inference.

- FLOPs. It quantifies the computational complexity of model, serve as a key metric for evaluating model efficiency.

4.4. Ablation Analysis of Network Structures

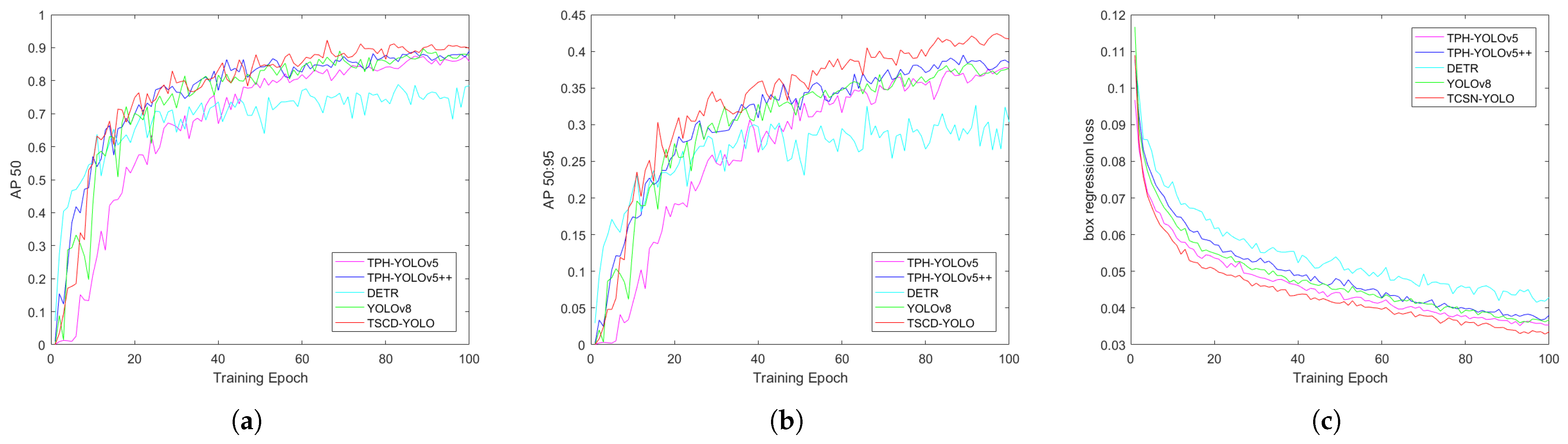

4.5. Comparison with Mainstream Methods

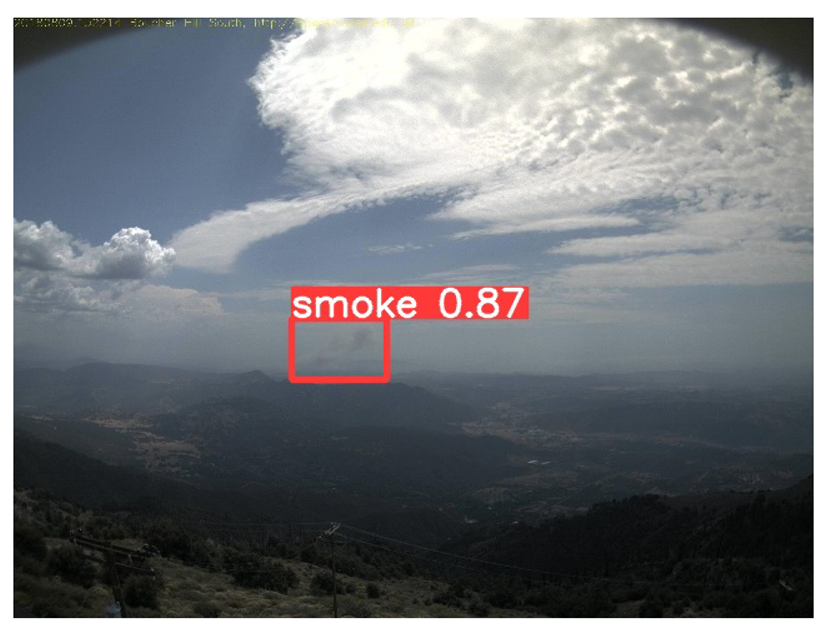

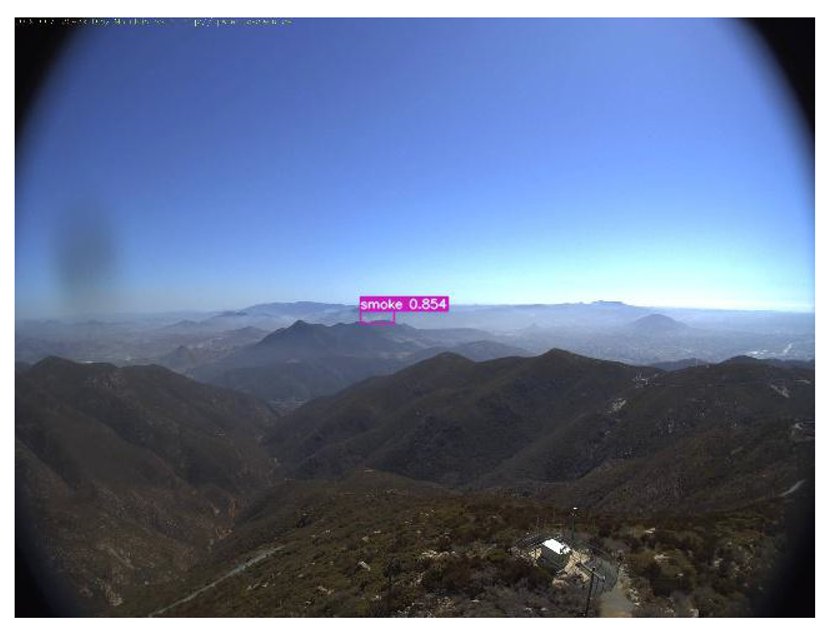

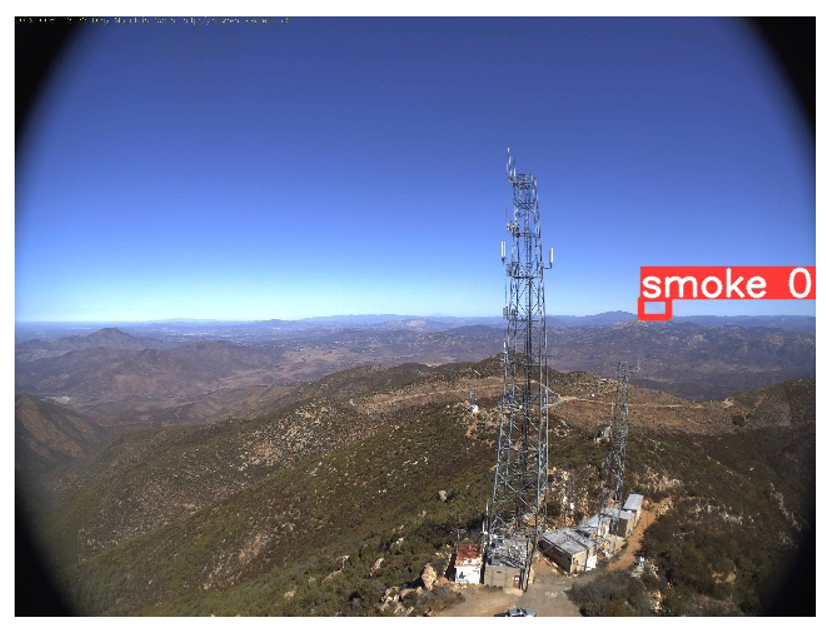

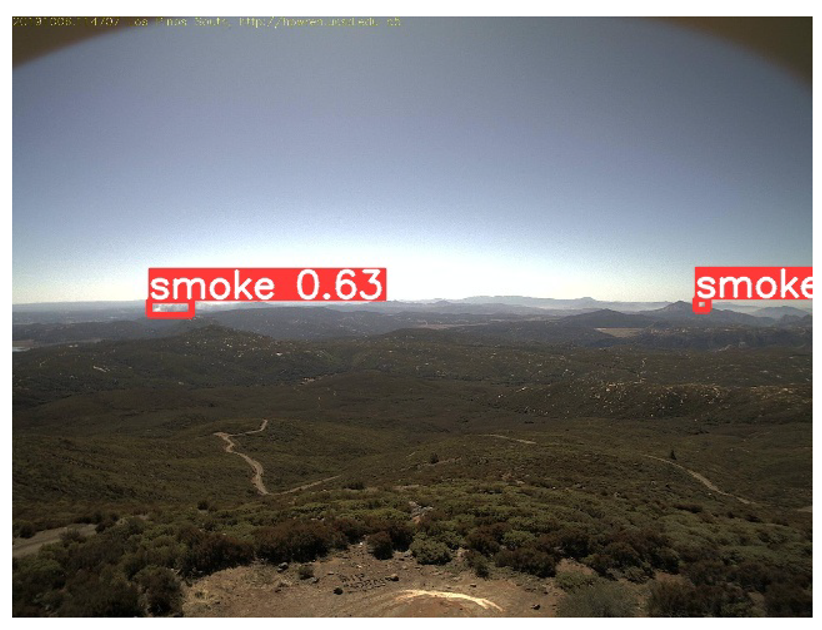

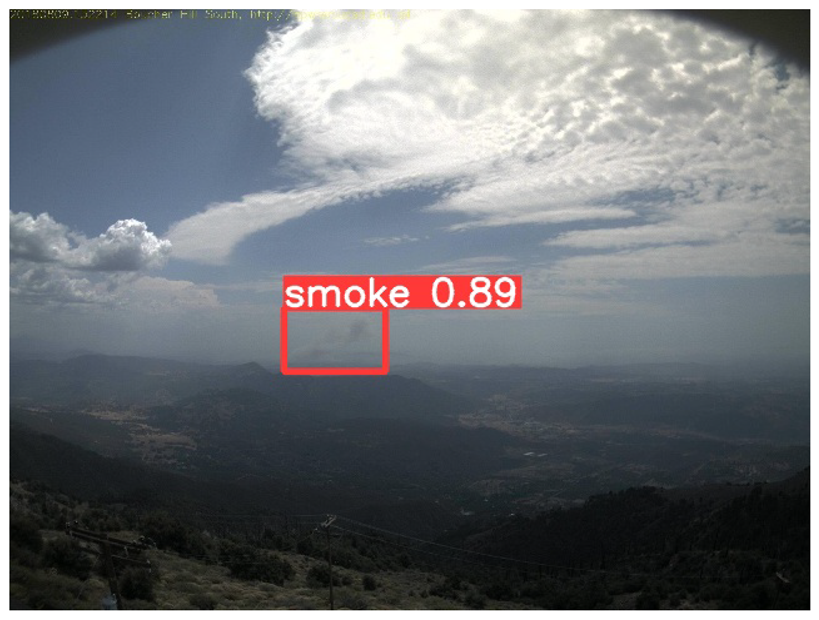

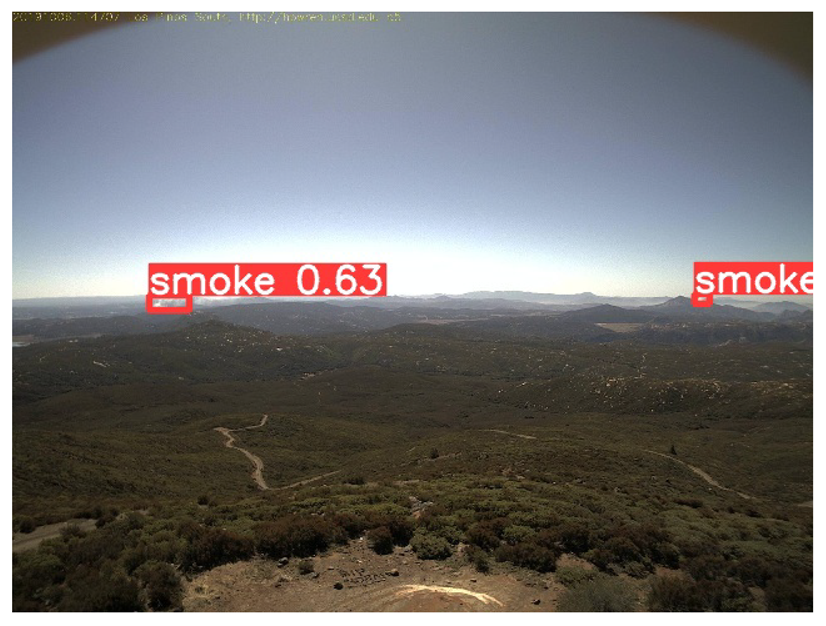

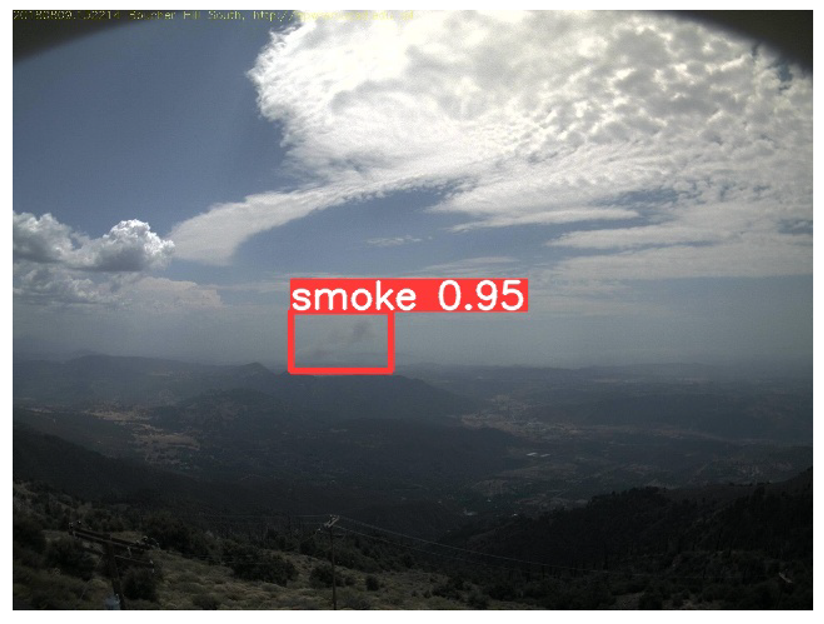

4.6. Generalization Experiment

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sathishkumar, V.E.; Cho, J.; Subramanian, M.; Naren, O.S. Forest fire and smoke detection using deep learning-based learning without forgetting. Fire Ecol. 2023, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Muminov, A. Forest fire smoke detection based on deep learning approaches and unmanned aerial vehicle images. Sensors 2023, 23, 5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınarer, G. Hybrid Backbone-Based Deep Learning Model for Early Detection of Forest Fire Smoke. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisantal, M.; Wojna, Z.; Murawski, J.; Naruniec, J.; Cho, K. Augmentation for small object detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07296. [Google Scholar]

- Geetha, S.; Abhishek, C.S.; Akshayanat, C.S. Machine vision based fire detection techniques: A survey. Fire Technol. 2021, 57, 591–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prema, C.E.; Suresh, S.; Krishnan, M.N.; Leema, N. A novel efficient video smoke detection algorithm using co-occurrence of local binary pattern variants. Fire Technol. 2022, 58, 3139–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonenko, A.; Hernández, D.C.; Jo, K.H. Fast smoke detection for video surveillance using CUDA. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 14, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, N.; Nguyen, K.; Chandran, V.; Boles, W. Combining multi-channel color space with local binary co-occurrence feature descriptors for accurate smoke detection from surveillance videos. Fire Saf. J. 2018, 102, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mihaylova, L.S.; Isupova, O.; Rossi, L. Autonomous flame detection in videos with a Dirichlet process Gaussian mixture color model. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 14, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstinić, D.; Stipaničev, D.; Jakovčević, T. Histogram-based smoke segmentation in forest fire detection system. Inf. Technol. Control 2009, 38, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, T.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Safran, M.; Mridha, M.F.; Dey, N. Deep learning-based multistage fire detection system and emerging direction. Fire 2024, 7, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C. A lightweight smoke detection network incorporated with the edge cue. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, R.; Chen, C.; Yuan, J.; Song, W.; Lo, S. SmokeNet: Satellite smoke scene detection using convolutional neural network with spatial and channel-wise attention. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, M.; Farajzadeh, N.; Heydari, M. Smoke detection in video using convolutional neural networks and efficient spatio-temporal features. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 128, 109496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S.; Alenezi, F.; Masood, S.; Ahmad, M.; Gündüz, E.S.; Polat, K. Attention based CNN model for fire detection and localization in real-world images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 189, 116114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Muhammad, K.; Hussain, T.; Del Ser, J.; Cuzzolin, F.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Akhtar, Z.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C. Deepsmoke: Deep learning model for smoke detection and segmentation in outdoor environments. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 182, 115125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Farajzadeh, N. UFS-Net: A unified flame and smoke detection method for early detection of fire in video surveillance applications using CNNs. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 61, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lyu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. TPH-YOLOv5: Improved YOLOv5 based on transformer prediction head for object detection on drone-captured scenarios. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11 October 2021; pp. 2778–2788. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, B.; Lyu, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H. Tph-yolov5++: Boosting object detection on drone-captured scenarios with cross-layer asymmetric transformer. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, A.; Huroon, A.M.; Chang, H.T.; Tai, L.C. Dynamic fire and smoke detection module with enhanced feature integration and attention mechanisms. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2025, 28, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahhar, C.; Ksibi, A.; Ayadi, M.; Jamjoom, M.M.; Ullah, Z.; Soufiene, B.O.; Sakli, H. Wildfire and smoke detection using staged YOLO model and ensemble CNN. Electronics 2023, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, D.K.; Ryu, J.K. A study on the dynamic image-based dark channel prior and smoke detection using deep learning. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2022, 17, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Park, M.; Nam, J.; Ko, B.C. Light-Weight Student LSTM for Real-Time Wildfire Smoke Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 17 March 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Safarov, F.; Muksimova, S.; Kamoliddin, M.; Cho, Y.I. Fire and Smoke Detection in Complex Environments. Fire 2024, 7, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohra, A.; Yin, B.; Bilal, H.; Kumar, A.; Ali, M.; Li, Y. MSFFNet: Multi-scale feature fusion network with semantic optimization for crowd counting. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2025, 28, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Parihar, A.S. Bff: Bi-stream feature fusion for object detection in hazy environment. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 3097–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Le, Q.V. Nas-fpn: Learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16 June 2019; pp. 7036–7045. [Google Scholar]

- Achinek, D.N.; Shehu, I.S.; Athuman, A.M.; Fu, X. DAF-Net: Dense attention feature pyramid network for multiscale object detection. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Focaler-iou: More focused intersection over union loss. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10525. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Yang, W.; Yu, L. A normalized Gaussian Wasserstein distance for tiny object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.13389. [Google Scholar]

- HPWREN/AI for Mankind. Available online: https://github.com/aiformankind/wildfire-smoke-dataset (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Dewangan, A.; Pande, Y.; Braun, H.W.; Vernon, F.; Perez, I.; Altintas, I.; Cottrell, G.W.; Nguyen, M.H. FIgLib & SmokeyNet: Dataset and deep learning model for real-time wildland fire smoke detection. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1007. [Google Scholar]

| Hardware environment | CPU | Intel Xeon Gold 6330 |

| RAM | 64 G | |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 | |

| Video memory | 16 G | |

| Software environment | OS | Ubuntu 18.04 |

| language | Python 3.8 | |

| framework | Pytorch 1.9.0 |

| Baseline | TF | CAM | SoftPool | NWD-Loss | (%) | (%) | APs (%) | (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 88.4 | 37.8 | 36.4 | 56.8 | 43.71 | 165.2 | ||||

| ✓ | ✓ | 89.5 | 38.7 | 36.9 | 57.4 | 43.76 | 166.1 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 88.9 | 38.2 | 36.6 | 58.2 | 44.18 | 167.4 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 88.6 | 38.1 | 36.5 | 57.1 | 43.82 | 165.9 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 88.9 | 38.5 | 37.0 | 56.9 | 43.71 | 165.4 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 90.3 | 40.4 | 37.1 | 61.6 | 45.34 | 170.5 |

| Model | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPH-YOLOv5 | 87.5 | 37.5 | 35.1 | 58.0 | 45.36 | 260.1 |

| TPH-YOLOv5++ | 87.7 | 38.8 | 36.1 | 59.5 | 41.49 | 160.0 |

| DETR | 78.8 | 30.0 | 29.6 | 55.4 | 60.28 | 253.6 |

| YOLOv8 | 88.4 | 37.8 | 36.4 | 56.8 | 43.71 | 165.2 |

| TCSN-YOLO (ours) | 90.3 | 40.4 | 37.1 | 61.6 | 45.34 | 170.5 |

| Model | Detection Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

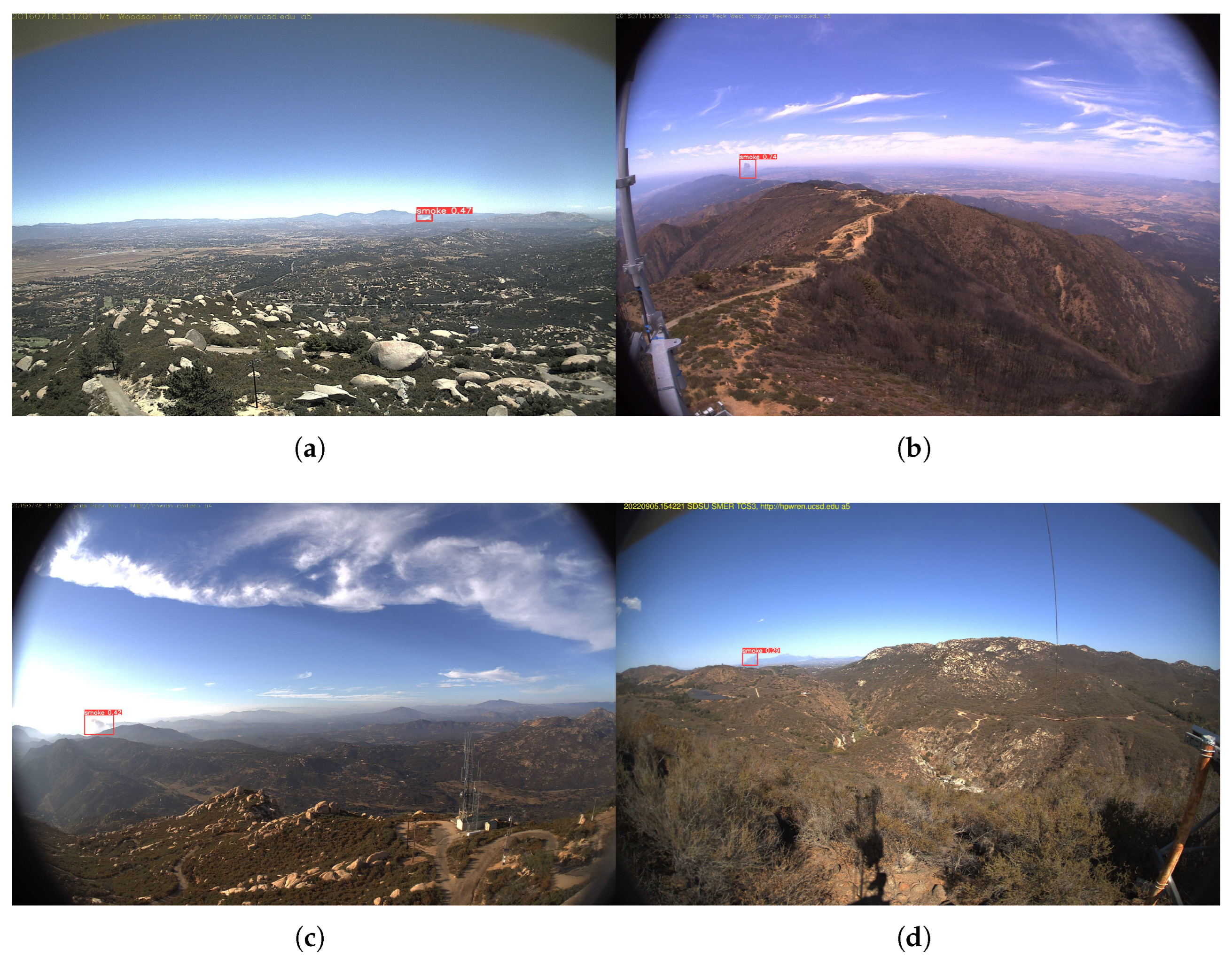

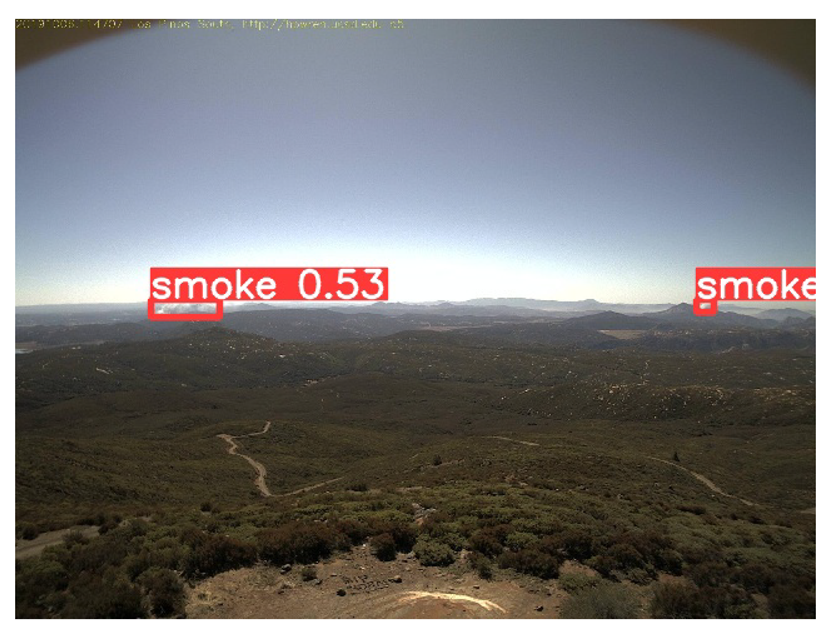

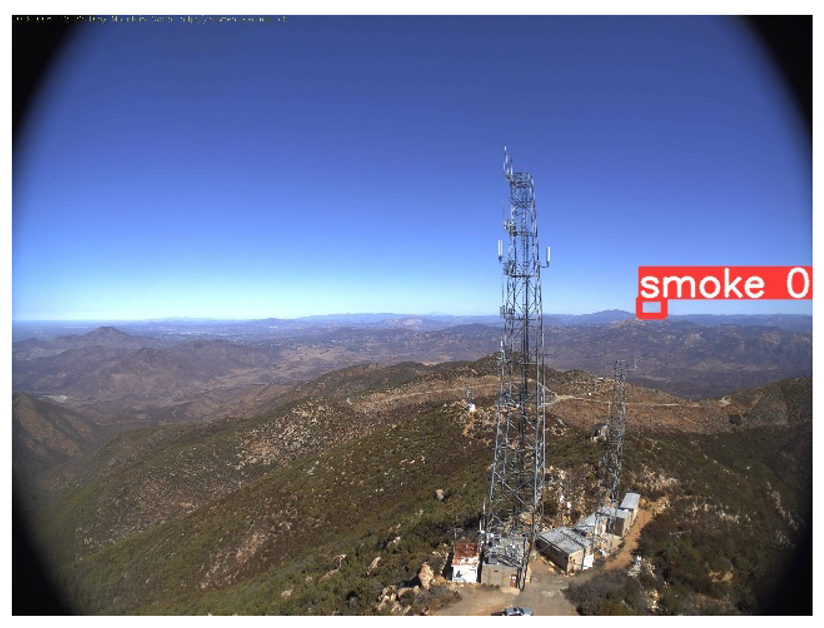

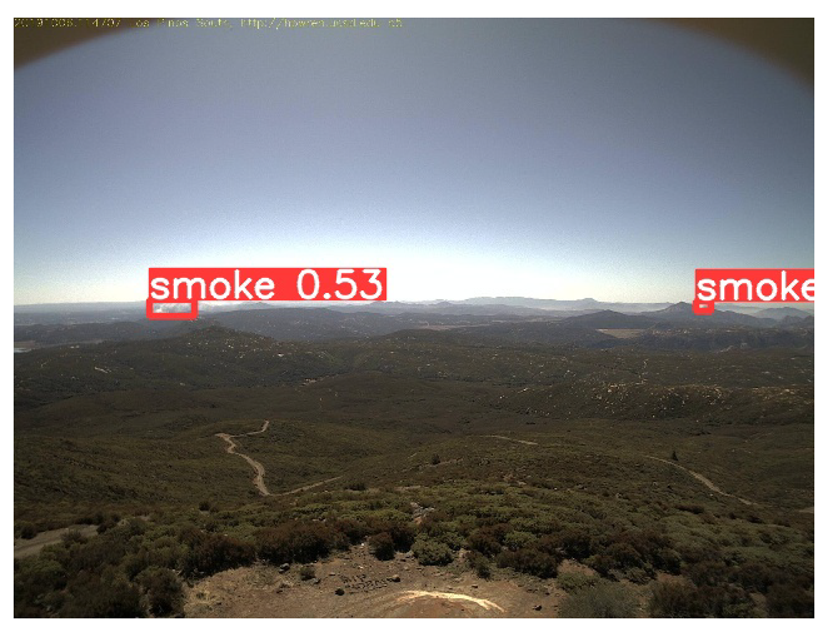

| TPH-YOLOv5 |  |  |  |  |

| TPH-YOLOv5++ |  |  |  |  |

| DETR |  |  |  |  |

| YOLOv8 |  |  |  |  |

| TCSN-YOLO |  |  |  |  |

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | |

| Model | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI For Humankind | 90.3 | 40.4 | 37.1 | 61.6 |

| FlgLib | 88.0 | 38.2 | 35.8 | 61.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, C.; Jun, Z.; Hongyuan, W.; Gang, W. TCSN-YOLO: A Small-Target Object Detection Method for Fire Smoke. Fire 2025, 8, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120466

Yang C, Jun Z, Hongyuan W, Gang W. TCSN-YOLO: A Small-Target Object Detection Method for Fire Smoke. Fire. 2025; 8(12):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120466

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Cao, Zhou Jun, Wen Hongyuan, and Wang Gang. 2025. "TCSN-YOLO: A Small-Target Object Detection Method for Fire Smoke" Fire 8, no. 12: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120466

APA StyleYang, C., Jun, Z., Hongyuan, W., & Gang, W. (2025). TCSN-YOLO: A Small-Target Object Detection Method for Fire Smoke. Fire, 8(12), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120466