Fire Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber: A Review of Standards, Experimental Testing, and Numerical Modelling Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

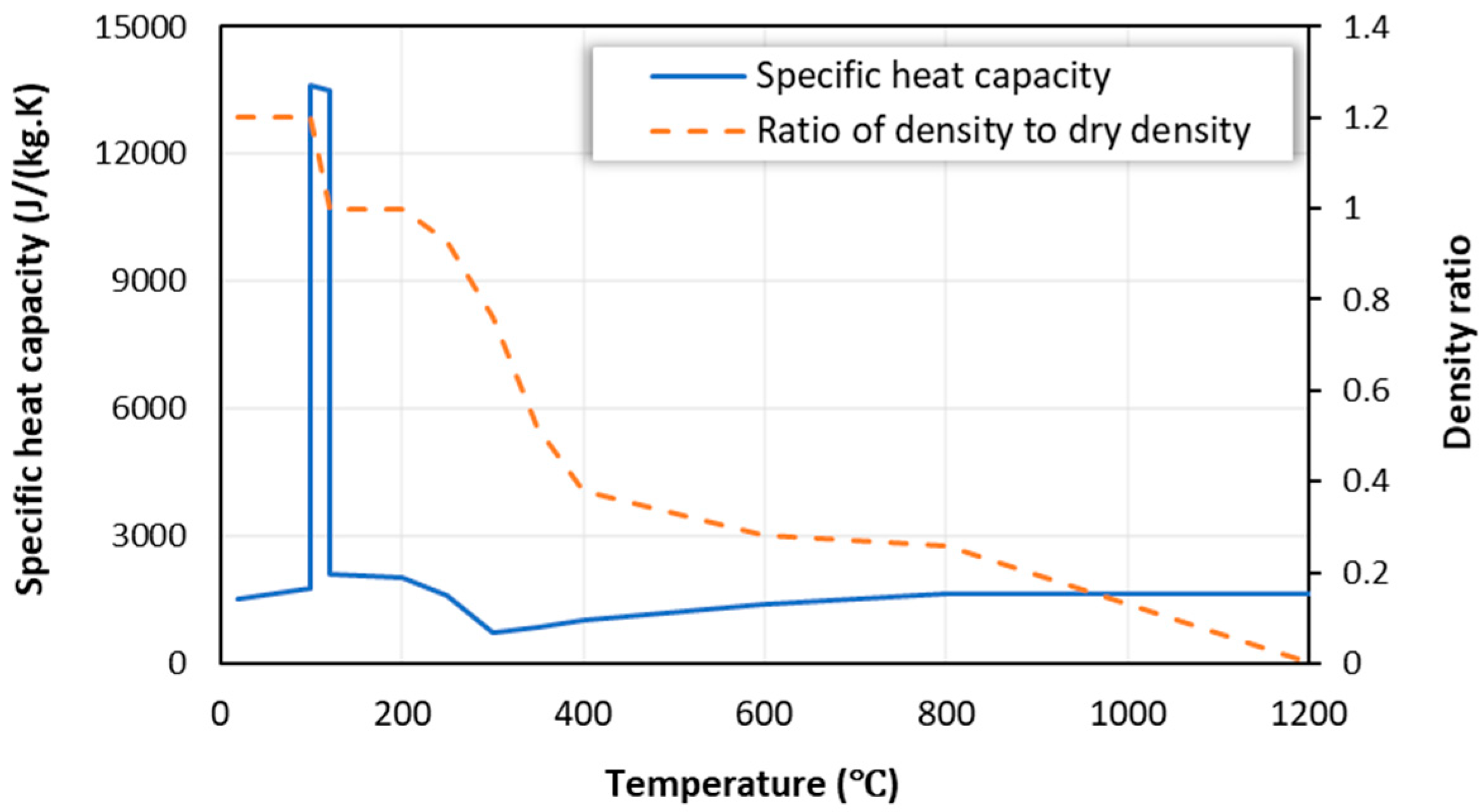

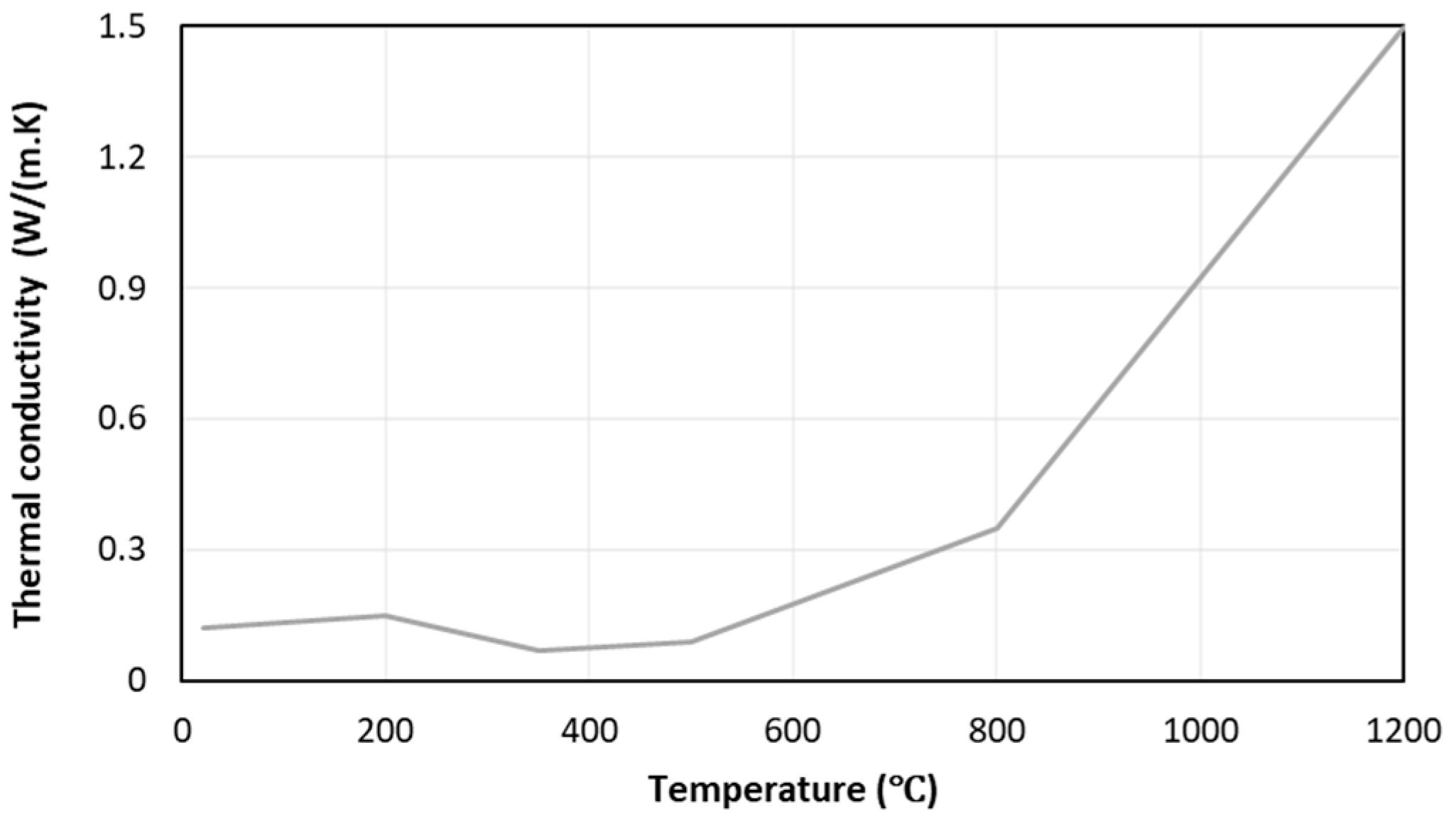

2. Thermal Response of Timber and CLT

3. Structural Integrity of CLT in Fire

3.1. Determination of Cross-Sectional Properties

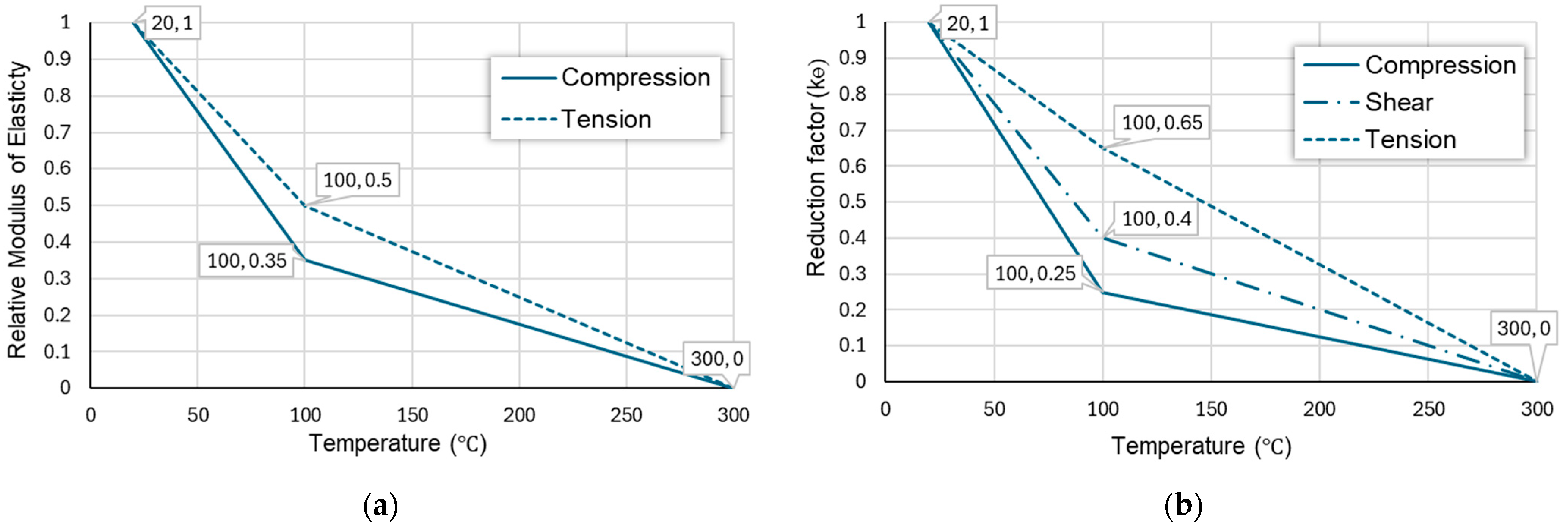

3.2. Effects of Fire on Mechanical Properties

4. Fire Protection Measures for CLT

4.1. Design Considerations for Fire Protection (EN 1995)

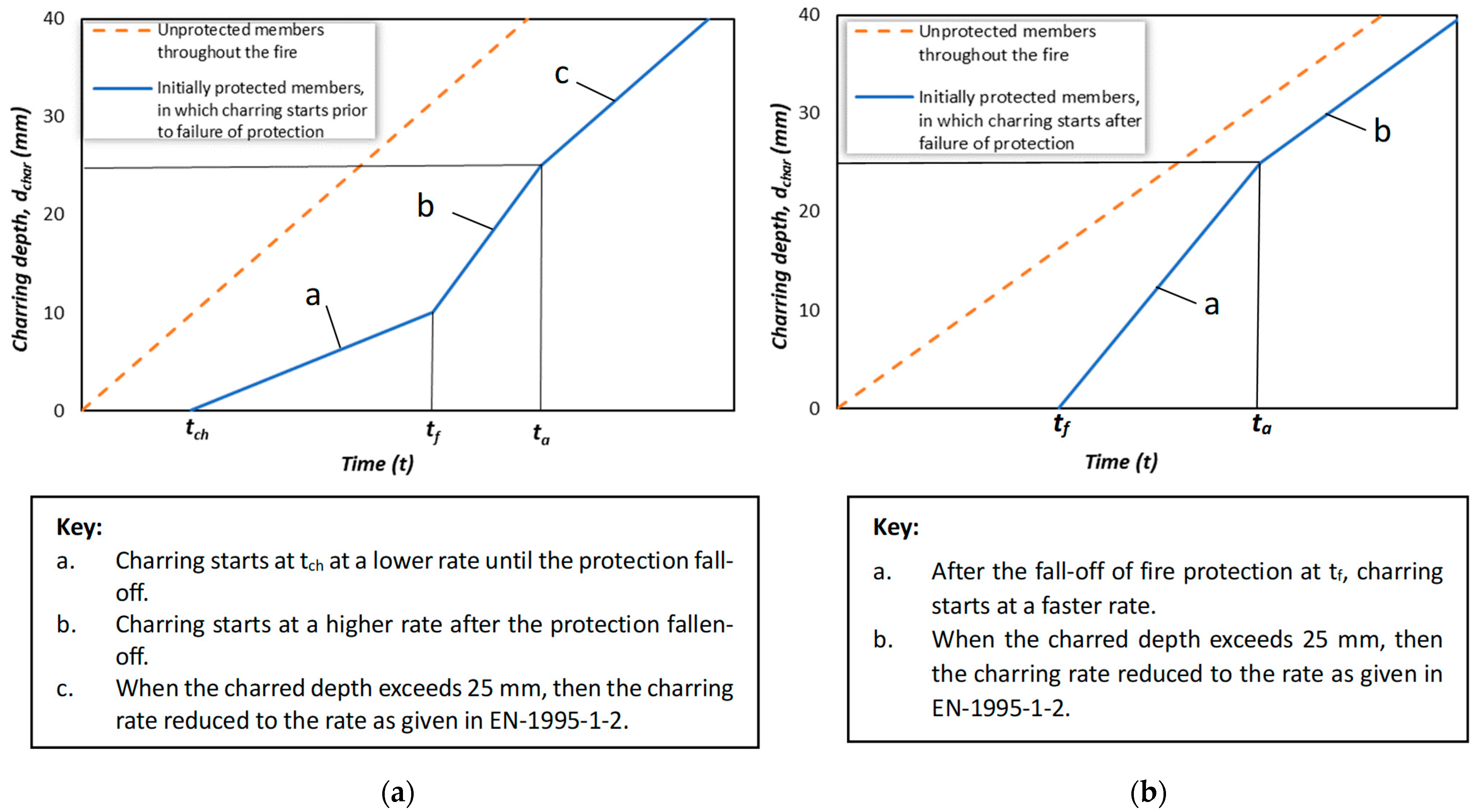

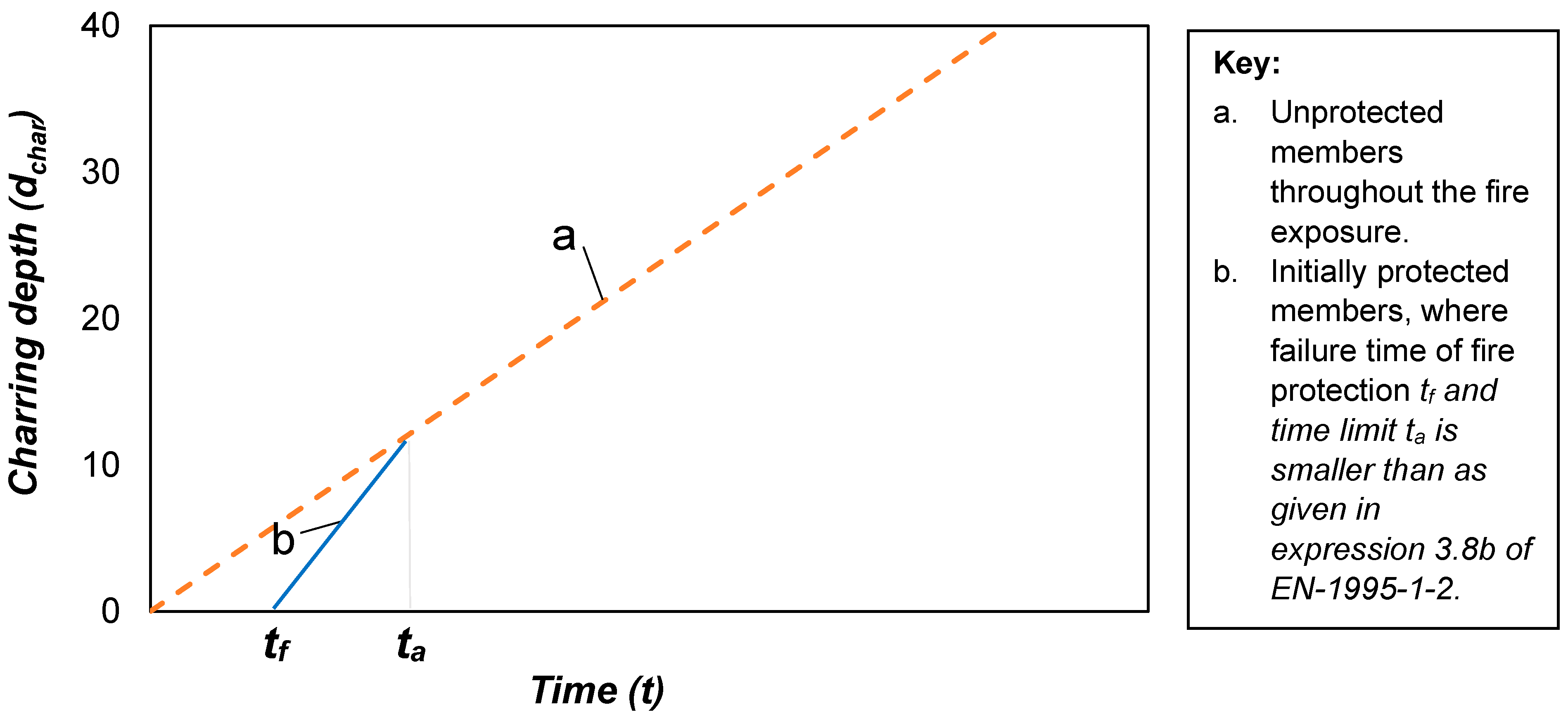

- No charring will occur until time tch (time of start of charring behind the protective layer).

- The charring rate increases above the values shown in Table 2 after the failure time, t

f, of the fire protective cladding until time ta. - At time ta, the charring rate returns to the values as specified in Table 2, when the charred depth is the least of either the charring depth of the same element with no fire protection or 25 mm.

4.1.1. Charring Rate for Initially Protected Components

- For tch ≤ t ≤ tf, EN 1995-1-2 [16] provides a factor, k2 (insulation coefficient), that needs to be multiplied by the charring rate.

4.1.2. Start of Charring for Initially Protected Components and Their Failure Times

4.1.3. Challenges in Implementing Fire Protection Technologies

5. International Standards

5.1. Canadian Standard CSA O86

5.2. American Standards: NDS

5.3. Australian and New Zealand Standards (AS 1720.4)

5.4. Review of Standards and Practical Implications

6. Case Studies and Experimental Research

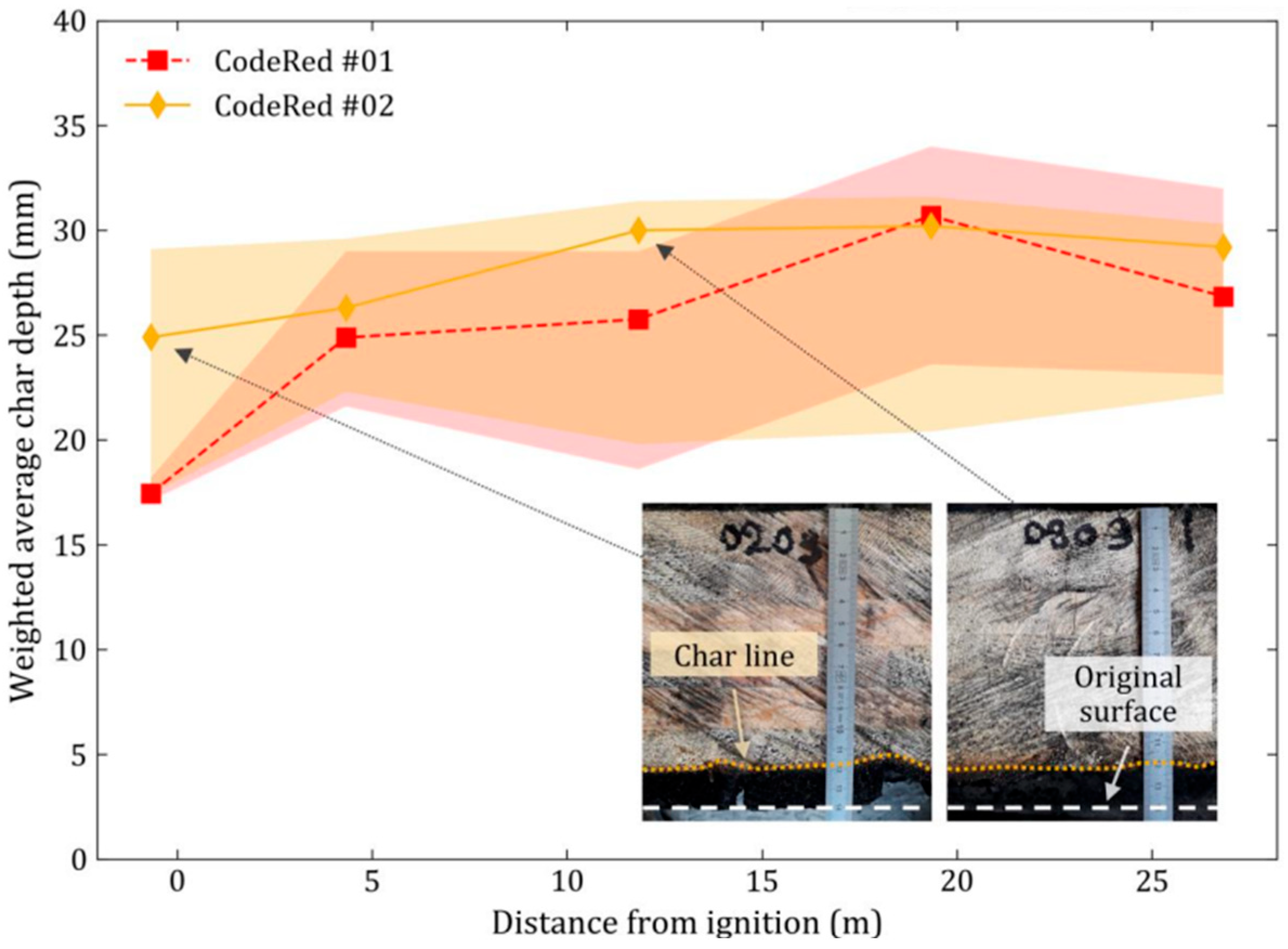

6.1. Overview of CLT Fire Resistance Tests

6.1.1. Loading and Support Conditions

6.1.2. Wood Grade and Density

6.1.3. Orientation and Setup of CLT Layers

6.1.4. Layer Thickness

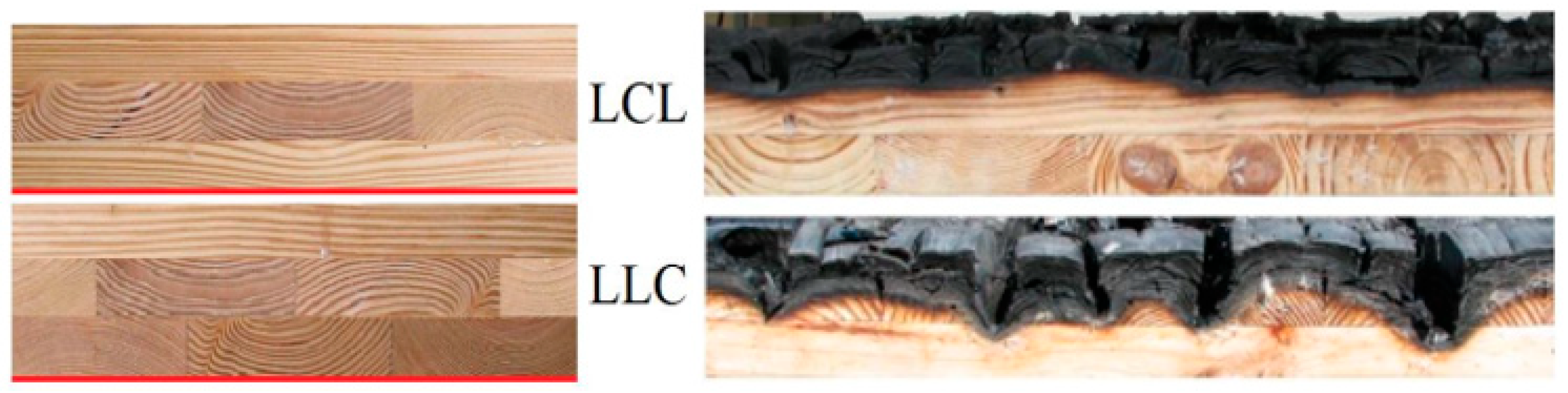

6.1.5. Type of Adhesive

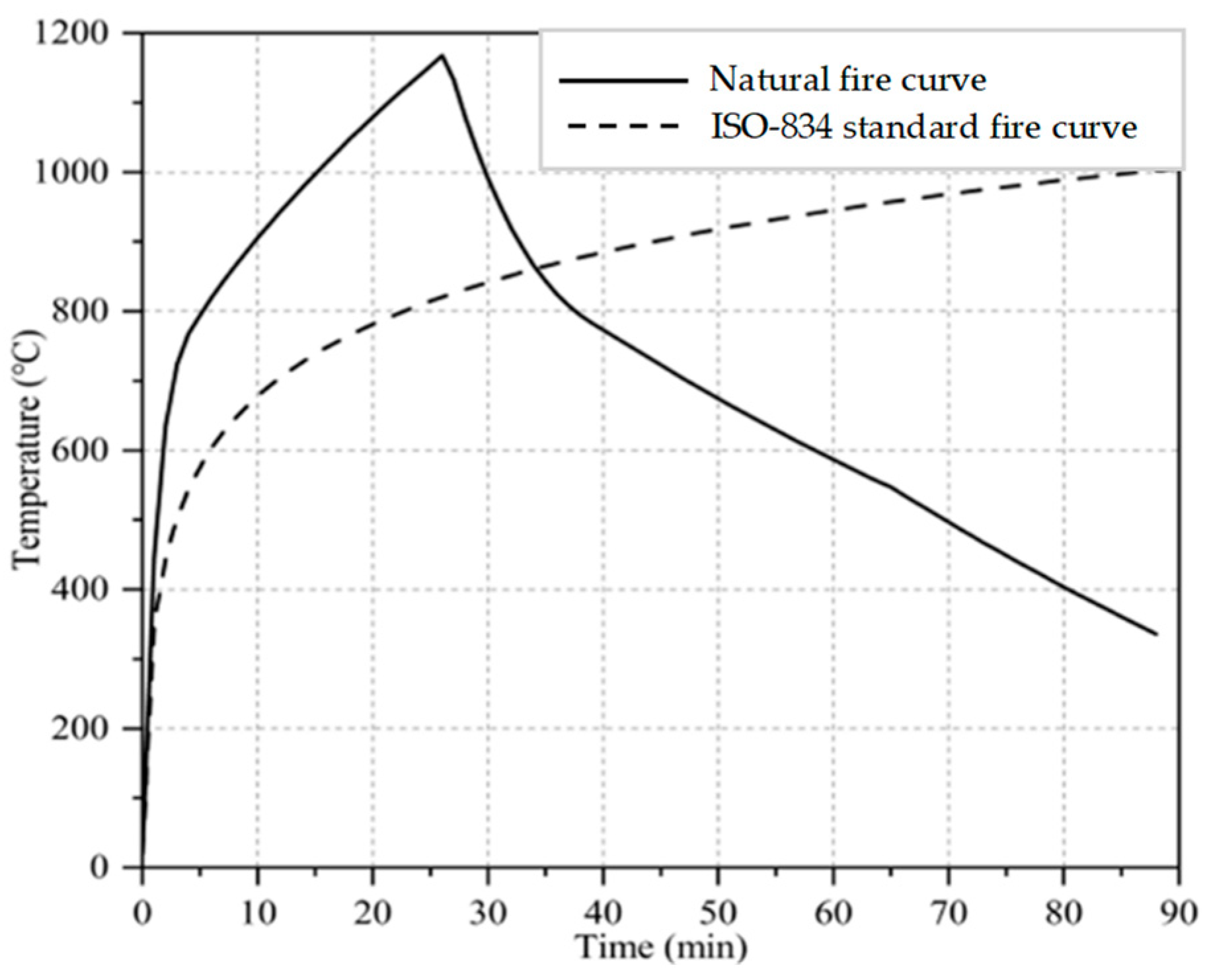

6.1.6. Fire Curve and Fuel Load

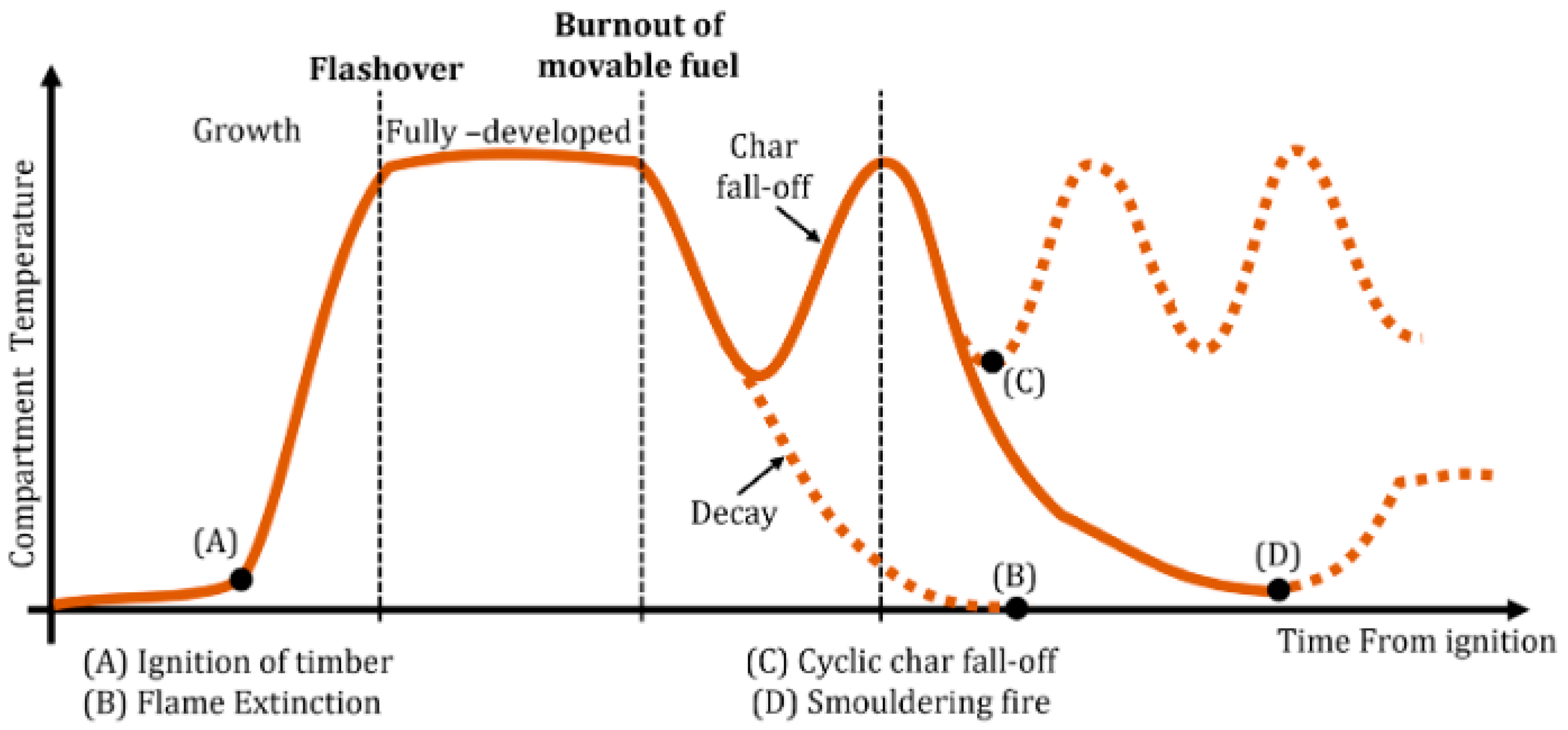

6.2. CLT Fire Compartment Tests

6.2.1. Protective Layers

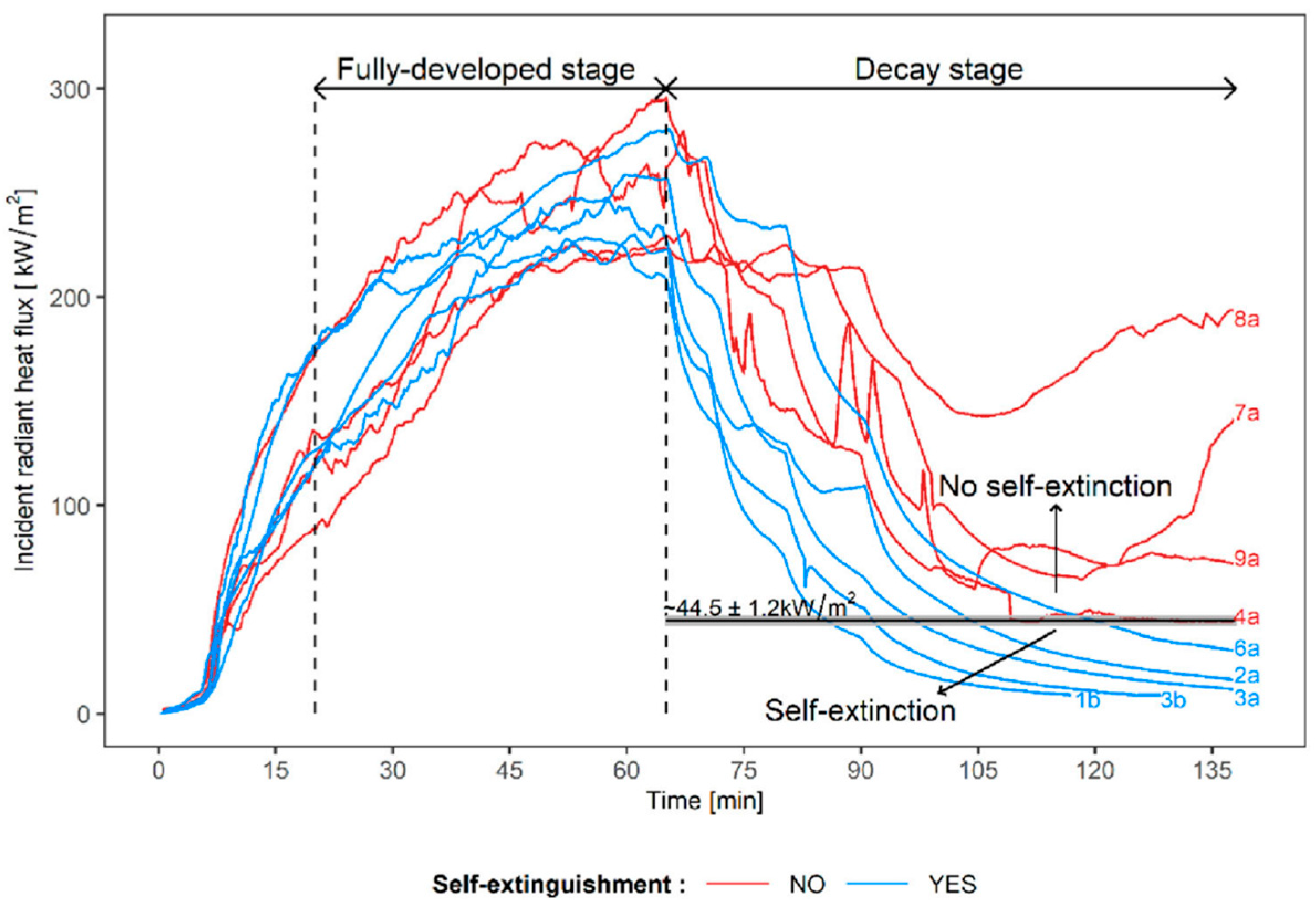

6.2.2. Size of Opening/Ventilation

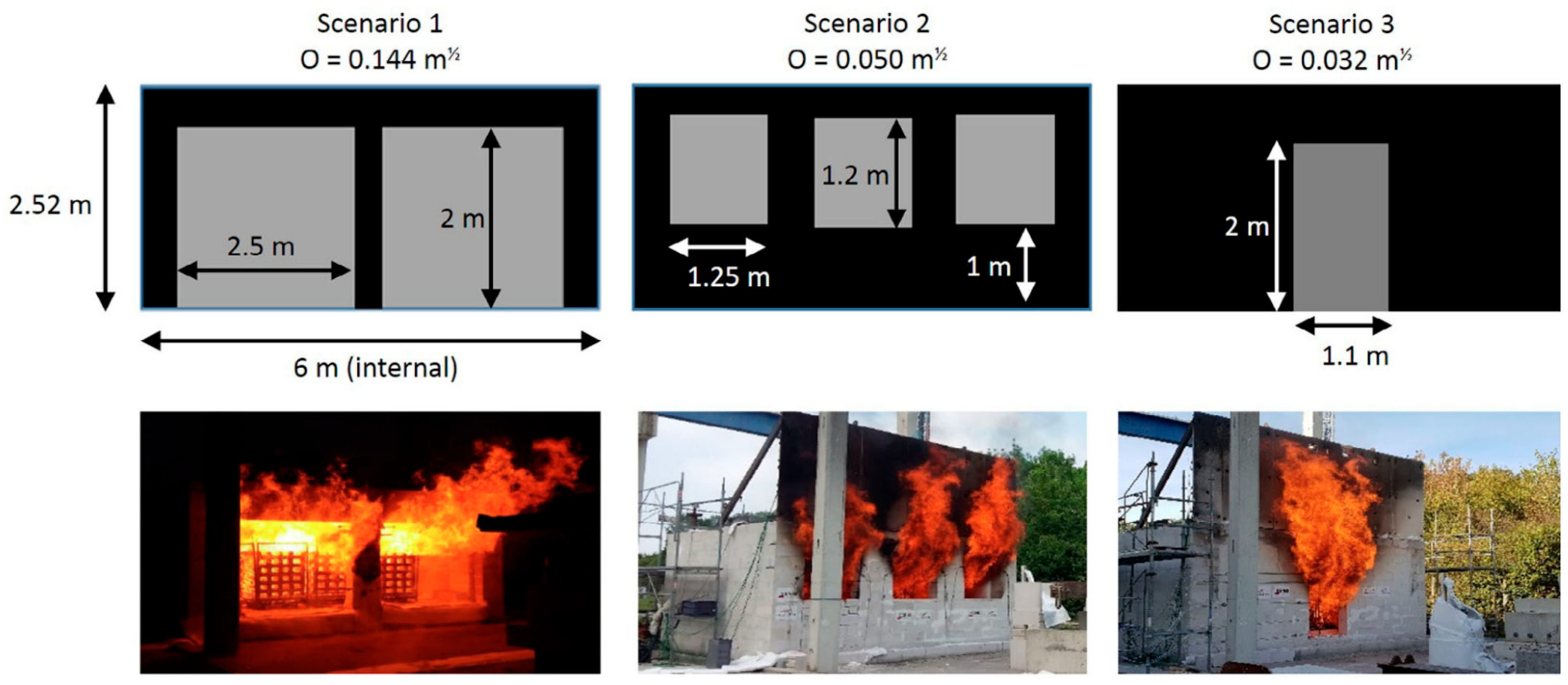

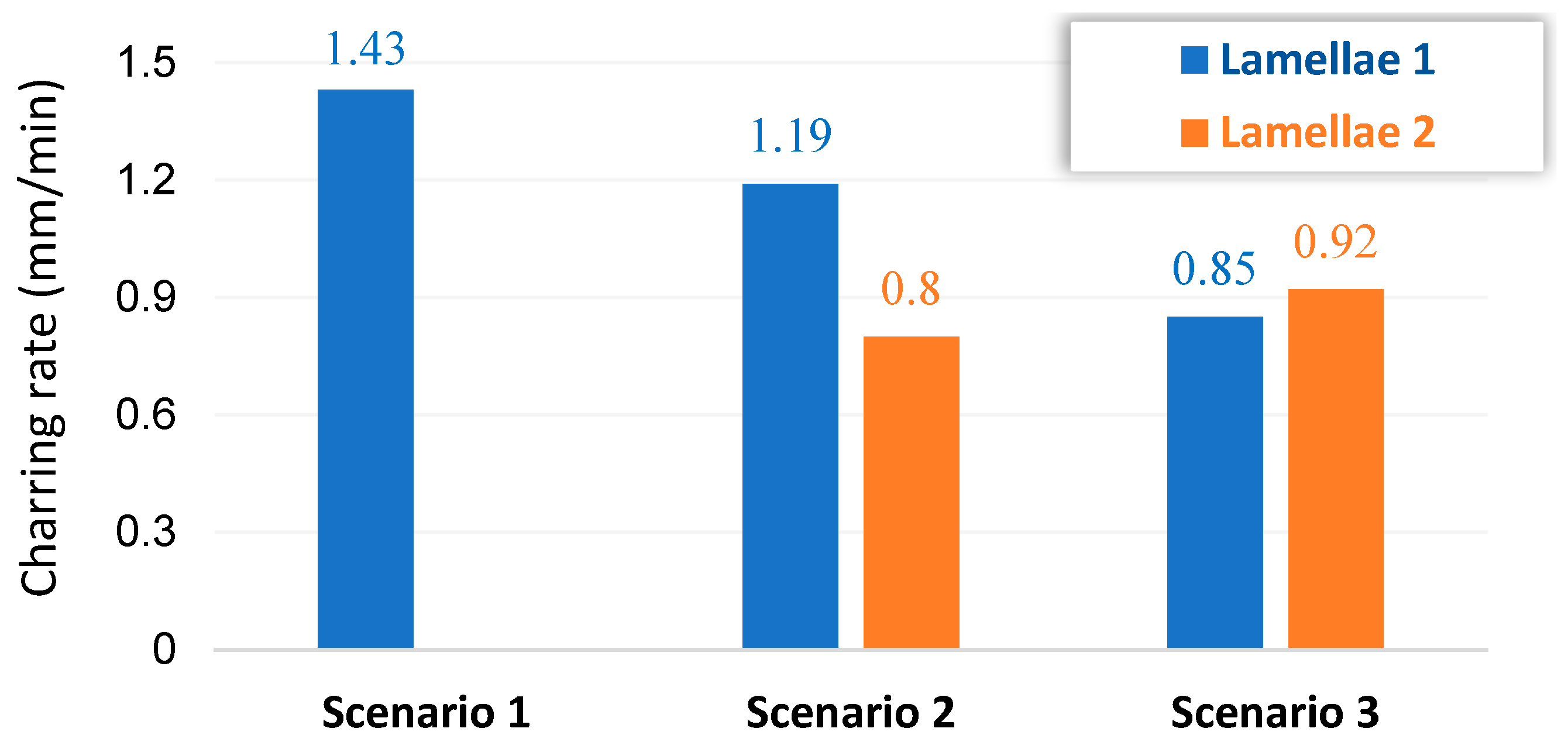

6.3. Discussion on the Limitations of Experimental Research

7. Numerical Studies

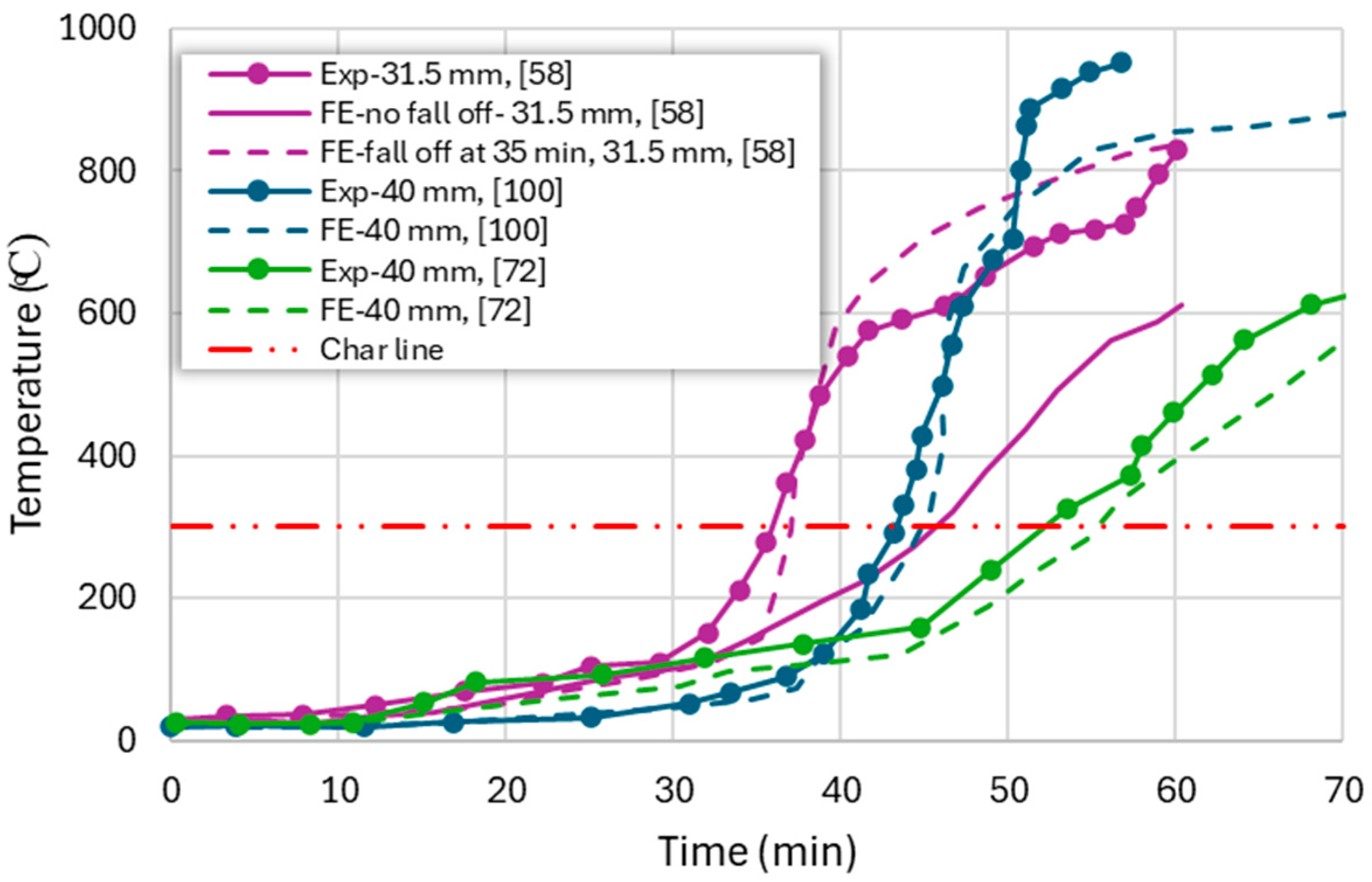

7.1. Modelling of Heat Transfer in CLT

7.2. Mesh Size

7.3. Deactivation of the Charred Layer

7.4. Fire Resistance of CLT

8. Conclusions

- Adhesives play a crucial role in the behaviour of CLT elements under fire exposure. Non-heat-resistant adhesives like PUR are typically shown to lead to more delamination or fall-off of charred layers compared to MF- or PRF-based adhesive panels.

- CLT panels with thicker outer layers exhibit better fire performance than those with thinner outer layers because a charred layer develops without fall-off, protecting the inner layer from direct fire exposure.

- There was found to be no significant influence of the orientation of the CLT layers or support conditions and grade on the fire behaviour or charring rate of CLT panels.

- Fire intensity and duration affect the performance of CLT and should be considered, as a higher charring rate has been observed for natural fires compared to standard fires.

- CLT compartments having different protective claddings showed their effectiveness in delaying the charring of the CLT structure, as well as reducing the initial char rate when charring behind the claddings initiates. Furthermore, the fire protection in CLT compartments has a significant effect on the HRR, with a substantial decrease in the HRR when protective cladding is used.

- The size of the opening or ventilation is another key factor that controls the temperature, fire development, and behaviour of the CLT structure. Compartments with more openings have higher charring rates than those with smaller openings. This is because compartments with larger ventilation accelerate combustion with a higher peak HRR for shorter durations. In contrast, compartments with smaller ventilation extend the fire duration, causing an overall higher char depth than compartments with large ventilation.

Future Research and Development

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CLT | Cross-laminated timber |

| EWP | Engineered wood product |

| FE | finite element |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| LVL | Laminated veneer lumber |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MF | Melamine formaldehyde |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MUF | Melamine urea formaldehyde |

| PISM | Physics-Informed Surrogate Modelling |

| PRF | Phenol resorcinol formaldehyde |

| PUR | Polyurethane |

Appendix A

| Authors | Fire Curve | Wood Species | Density (kg/m3) and/or Wood Grade | Layers Layout (mm) | M.C (%) | Adhesive | Dimensions (mm × mm × mm) | Charring Rate (mm/min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | W | T | ||||||||

| Friquin et al. [69] | Parametric | Norway spruce | 440 | 19.5-30-21-30-19.5 | 8–9.3 | MUF | 3600 | 1200 | 120 | 0.95 |

| 29.5-39-32-39-32-39-29.5 | 240 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| Standard | 32-41-34-41-32 | 180 | 0.48 | |||||||

| 31.5-21-32-21-32-21-32-21-28.5 | 240 | 0.71 | ||||||||

| Swedish | 19.5-30-21-30-19.5 | 120 | 0.50 | |||||||

| 29.5-39-32-39-32-39-29.5 | 240 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| Muszyński et al. [63] | Standard | Spruce–pine–fir | 472 | 35-35-35-35-35 | 10.3 | PUR | 5486 | 4267 | 175 | 0.61 |

| Douglas fir–larch | 532 | 35-35-35-35-35 | 12.2 | PUR | 0.63 | |||||

| Douglas fir–larch | 554 | 35-35-35-35-35 | 13.0 | MF | 0.55 | |||||

| Frangi et al. [57] | Standard | Spruce | 405–486 | 10-10-10-10-20 | 10 | MUF | 1150 | 950 | 60 | 0.58 |

| PU1 | 0.94 | |||||||||

| PU2 | 0.90 | |||||||||

| PU3 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| PU4 | 1.08 | |||||||||

| 20-20-20 | PU3 | 0.85 | ||||||||

| PU4 | 0.89 | |||||||||

| PU5 | 0.76 | |||||||||

| 30-30 | MUF | 0.61 | ||||||||

| PU1 | 0.80 | |||||||||

| Klippel et al. [67] | Standard | Spruce–pine–fir | C16 | 34-19-34-19-34 | 12 | PUR | 4800 | 1200 | 140 | 0.81 |

| 34-24-24-24-34 | 0.78 | |||||||||

| Mindeguia et al. [27] | Standard | Spruce | C24 | 33-33-33-33-33 | 11.6–12.6 | PUR | 5900 | 3900 | 165 | 0.71–0.75 |

| Xing et al. [35] | Standard | 580 | 33-33-33 | 12 ± 0.7 | PUR | 3400 | 420 | 105 | 0.67 | |

| 21-21-21-21-21 | 0.77 | |||||||||

| Natural fire | 33-33-33 | 0.92 | ||||||||

| 21-21-21-21-21 | 1.18 | |||||||||

| Hasburgh et al. [75] | Standard | Southern pine | Not provided | 35-35-35 | MF | 1194 | 965 | 105 | 0.67 | |

| PRF | 0.73 | |||||||||

| PUR | 0.70 | |||||||||

| EPI | 0.73 | |||||||||

| 35-35-35-35-35 | PUR | 175 | 0.68 | |||||||

| PRF | 0.67 | |||||||||

| Wang et al. [58] | Standard | Canadian hemlock lumber | 480 | 35-35-35 | 13 | PUR | 2200 | 420 | 105 | 0.95 |

| 21-21-21-21-21 | 0.92 | |||||||||

| Lucherini et al. [73] | 50 kW/m2 | Australian softwood | - | 20-20-20-20-20 | - | - | 200 | 200 | 100 | 0.76 |

| Suzuki et al. [76] | Standard | Japanese cedar | 19.3 mm × 7 plies | 12.2 | RPF | 1500 | 450 | 135 | 0.66 | |

| 27 mm × 5 plies | 13.1 | API | 0.70 | |||||||

| 45 mm × 3 plies | 11.4 | 0.76 | ||||||||

| 19.3 mm × 7 plies | 12.3 | 0.70 | ||||||||

| Japanese larch | 19.3 mm × 7 plies | 9.5 | 0.64 | |||||||

| Authors and Reference | Fire Curve | Wood Species | Density (kg/m3) or Grade | Layers Layout (mm) | M.C (%) | Adhesive | Dimensions (mm × mm × mm) | Load | Charring Rate (mm/min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | W | T | (kN) | ||||||||

| Westhuyzen et al. [70] | Standard | SA pine | 479 | 33-33-33 | 14.2 | PUR | 900 | 900 | 100 | 0.95 | |

| Eucalyptus | 552 | 33-33-33 | 14.8 | 0.76 | |||||||

| Yasir et al. [42] | Standard | Irish spruce | 381 (C16) | 40-40-40 | 12–13 | PUR | 1200 | 900 | 120 | 85 | 0.66 |

| Aloisio et al. (2025) [82] | Standard | - | 450 | 6 × 30 = 180 | None, Wooden Dowels | 2980 | 3000 | 180 | 50 kN/m | 0.9 | |

| Klippel et al. [67] | Standard | Spruce–pine–fir | C16 | 34-34-34 a | 12 | PUR | 3000 | 480 | 102 | 0.64 | |

| 34-34-34 b | 0.72 | ||||||||||

| 34-19-34-19-34 a | 660 | 140 | 0.74 | ||||||||

| 34-19-34-19-34 b | 0.74 | ||||||||||

| 34-24-24-24-34 a | 0.74 | ||||||||||

| 34-24-24-24-34 b | 0.73 | ||||||||||

| Bartlett et al. [14] | Standard | Sitka spruce (426) Scotts pine (501) | 40-40-40 | No data | PUR | 300 | 200 | 120 | 0.70 | ||

| Slow heating fire curve | 0.59 | ||||||||||

| 8.33 W/m2min2 | 0.43 | ||||||||||

| 12.5 W/m2min2 | 0.45 | ||||||||||

| 16.7W/m2min2 | 0.48 | ||||||||||

| Wiesner et al. [74] | heat flux of 50 kW/m2 | Spruce and pine | Not given | 33-34-33 | 10.3 | MF | 1700 | 300 | 100 | 44.1 | 0.82 |

| 33-34-33 | 88.2 | 0.88 | |||||||||

| 20-20-20-20-20 | 40.8 | 0.98 | |||||||||

| 20-20-20-20-20 | 81.6 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Frangi et al. [71] | Standard | 28-28-28 | PUR | 84 | 0.68 | ||||||

| 17-17-17-17-17 | 0.64 | ||||||||||

| Authors | Wood Species | Density (kg/m3) | Layers Layout (mm) | M.C (%) | Adhesive | Fire/Heat Curve | Type of Protection | Delay in Charring (min) | Charring Rate (mm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moser et al. [68] | Radiata pine | 460 ± 13 | 35-35-35 | 9 ± 1 | No data | 50 kW/m2 | Gypsum board, 13 mm | 24 | 0.61 |

| 65 kW/m2 | 22.5 | 0.40 | |||||||

| 50 kW/m2 | Gypsum board (FR), 13 mm | 26.5 | 0.48 | ||||||

| 65 kW/m2 | 24.5 | 0.55 | |||||||

| 50 kW/m2 | MgO board, 12 mm | 18 | 0.48 | ||||||

| 65 kW/m2 | 15 | 0.56 | |||||||

| 50 kW/m2 | MgO board, 15 mm | 21.5 | 0.43 | ||||||

| 65 kW/m2 | 16.5 | 0.51 | |||||||

| 50 kW/m2 | Fire-rated fibrous board, 12.5 mm | 21.5 | 0.43 | ||||||

| 65 kW/m2 | 16.5 | 0.51 | |||||||

| Lucherini et al. [73] | Australian softwood | - | 20-20-20-20-20 | - | - | 50 kW/m2 | 0.60 mm WTF (0.51mm DFT) | 15 | 0.34 |

| 1.60 mm WTF (1.31 mm DFT) | 26 | 0.27 | |||||||

| 2.50 mm WTF (2.13 mm DFT) | 44 | 0.20 | |||||||

| Yasir et al. [72] | Irish Sitka spruce | 381 | 40-20-20-20-40 | 12 ± 1 | PUR | Standard | 12.5 mm Fireline gypsum plasterboard | 20 | 0.71 |

| 40-30-40 | 12.5 mm Fireline gypsum plasterboard and 12.5 mm Plywood | 25.5 | 0.74 | ||||||

| Yasir et al. [42] | Irish Sitka spruce | 381 | 40-40-40 | 12 ± 1 | PUR | Standard | 15 mm FireLine gypsum plasterboard with no joints | 30 | 0.44 |

| 15 mm FireLine gypsum plasterboard with joints | 25 | 0.46 | |||||||

| 12.5 mm FireLine gypsum plasterboard and 25 mm plywood with joints in both | 44 | 0.67 |

References

- ANSI/APA PRG 320; Standard for Performance-Rated Cross-Laminated Timber. APA—The Engineered Wood Association: Tacoma, WA, USA, 2019.

- Kurzinski, S.; Crovella, P.; Kremer, P. Overview of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) and Timber Structure Standards Across the World. Timber Constr. J. 2022, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S. The CLT Handbook, CLT Structures—Facts and Planning. Available online: https://www.woodcampus.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Swedish-Wood-CLT-Handbook.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Schickhofer, G.; Brandner, R.; Bauer, H. Introduction to CLT, Product Properties, Strength Classes. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference of COST Actions FP1402 & FP1404 KTH Building Materials, Cross Laminated Timber—A competitive wood product for visionary and fire safe buildings. Stockholm, Sweden, 10–11 March 2016; pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mestek, P.; Kreuzinger, H. Design of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT). In Proceedings of the 10th World Conference on Timber Engineering, Miyazaki, Japan, 2–5 June 2008; pp. 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoli, A.; D’Ambra, C.; Ceraldi, C.; Calderoni, B.; Prota, A. Sustainable Cross-Laminated Timber Structures in a Seismic Area: Overview and Future Trends. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Cross-Laminated Timber Market. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/european-cross-laminated-timber-market (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- De Araujo, V.; Christoforo, A. The Global Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Industry: A Systematic Review and a Sectoral Survey of Its Main Developers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahirah, Y.A.; Anwar, U.; Sh, L.; Ong, C.; Asniza, M.; Paridah, M. The properties of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT): A review. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2025, 138, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross Laminated Timber Market Profile’, State of Maine DECD Domestic Trade Baseline Study. Available online: https://www.maine.gov/decd/sites/maine.gov.decd/files/inline-files/Market%20Profile%20%20-%20Cross%20Laminated%20Timber.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- UNECE/FAO Forest Products Annual Market Review 2020–2021; FAO/UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Lan, K.; Favero, A.; Yao, Y.; Mendelsohn, R.O.; Wang, H.S.-H. Global land and carbon consequences of mass timber products. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoya, T.; Kawamoto, H.; Saka, S. Pyrolysis behaviors of wood and its constituent polymers at gasification temperature. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2007, 78, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.I.; Hadden, R.M.; Bisby, L.A.; Law, A. Analysis of Cross-Laminated Timber Charring Rates Upon Exposure to Non-Standard Heating Conditions. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference and Exhibition on Fire and Materials, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–4 February 2015; Interscience Communications Ltd.: Hampshire, UK, 2015; pp. 667–681. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, F.; Bisby, L. The structural capacity of laminated timber compression elements in fire: A meta-analysis. Fire Saf. J. 2019, 107, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1995-2-1; Eurocode 5: Design of Timber Structures. Part 1-2: General—Structural Fire Design. European Committee for Standardisation (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Thi, V.D.; Khelifa, M.; Oudjene, M.; Ganaoui, M.E.; Rogaume, Y. Finite element analysis of heat transfer through timber elements exposed to fire. Eng. Struct. 2017, 143, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Abu, A.K. Structural Design for Fire Safety, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, F.; Thomson, D.; Bisby, L. The effect of adhesive type and ply number on the compressive strength retention of CLT at elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 121156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Y.; Adji, R.P.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Nugroho, N.; Bahtiar, E.T.; Dwianto, W.; Karlinasari, L. Effect of Glue Spread on Bonding Strength, Delamination, and Wood Failure of Jabon Wood-Based Cross-Laminated Timber Using Cold-Setting Melamine-Based Adhesive. Polymers 2023, 15, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, B.; Bechle, N.J.; Rammer, D.R.; Zelinka, S.L. A Small-Scale Test to Examine Heat Delamination in Cross Laminated Timber (CLT). Forests 2021, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottingham University Blaze “Destroyed” Lab. 2014. Available online: https://news.sky.com/story/nottingham-university-blaze-destroyed-lab-10389935 (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- White, R.H.; Schaffer, E.L. Transient Moisture Gradient in Fire-Exposed Wood Slab. Wood Fiber Sci. 1981, 13, 17–38. Available online: https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/pdf1981/white81a.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Zelinka, S.L.; Hasburgh, L.E.; Bourne, K.J.; Tucholski, D.R.; Ouellette, J.P. Compartment Fire Testing of a Two-Story Mass Timber Building; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, S.; Gunawardena, T.; Mendis, P. Review of Experimental Testing and Fire Performance of Mass Timber Structures. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Svenningsson, A. Delamination of Cross-Laminated Timber and Its Impact on Fire Development | Focusing on Different Types of Adhesives. Report 5562; Division of Fire Safety Engineering, Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2018; ISSN 1402-3504. ISRN: LUTVDG/TVBB—5562—SE; Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8938664&fileOId=8943019 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Mindeguia, J.-C.; Mohaine, S.; Bisby, L.; Robert, F.; McNamee, R.; Bartlett, A.I. Thermo-mechanical behaviour of cross-laminated timber slabs under standard and natural fires. Fire Mater. 2020, 45, 866–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippel, M.; Schmid, J. Design of Cross-Laminated Timber in Fire. Struct. Eng. Int. 2017, 27, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, F.; Hadden, R.; Deeny, S.; Bisby, L. Structural fire engineering considerations for cross-laminated timber walls. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, F.; Bartlett, A.; Mohaine, S.; Robert, F.; McNamee, R.; Mindeguia, J.-C.; Bisby, L. Structural Capacity of One-Way Spanning Large-Scale Cross-Laminated Timber Slabs in Standard and Natural Fires. Fire Technol. 2021, 57, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Aslani, F. Clt Two-Way Slabs Fire Resistance Test and Numerical Simulation Analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, F.; Bisby, L.A.; Bartlett, A.I.; Hidalgo, J.P.; Santamaria, S.; Deeny, S.; Hadden, R.M. Structural capacity in fire of laminated timber elements in compartments with exposed timber surfaces. Eng. Struct. 2019, 179, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairo, M.; Silva, V.P.; Icimoto, F.H. Behavior of cross-laminated timber panels during and after an ISO-fire: An experimental analysis. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 834-1; Fire Resistance Test-Elements of Building Construction, Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Xing, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H. Comparative study on fire resistance and zero strength layer thickness of CLT floor under natural fire and standard fire. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, C.C. Effect of moisture content and temperature on the mechanical properties of wood: An analysis of immediate effects. Wood Fiber Sci. 1982, 14, 4–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wood Handbook—Wood as An Engineering Material; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2021.

- Frangi, A.; Schleifer, V.; Fontana, M.; Hugi, E. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Gypsum Plasterboards in Fire. Fire Technol. 2010, 46, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffey, J.R.; Cuerrier, P.; Carisse, G. A model for predicting heat transfer through gypsum-board/wood-stud walls exposed to fire. Fire Mater. 1994, 18, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, I. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Gypsum Boards and Their Influences on Fire Resistance of Gypsum Board Based Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stora Enso. Fire protection of CLT. Version 04/2013 AG. Stora Enso. 2013, p. 51. Available online: https://www.cltsk.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CLT-Documentation-on-fire-protection-EN.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Yasir, M.; Macilwraith, A.; O’Ceallaigh, C.; Ruane, K. Effect of protective cladding on the fire performance of vertically loaded cross-laminated timber (CLT) wall panels. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 2023, 8, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Ruane, K.; Jaksic, V. Numerical Analysis of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Wall Panels Under Fire. In Wood & Fire Safety 2024; Makovická Osvaldová, L., Hasburgh, L.E., Das, O., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Chan, Y.-Q.; Jonescu, E.; Stewart, I. Critical Challenges and Potential for Widespread Adoption of Mass Timber Construction in Australia—An Analysis of Industry Perceptions. Buildings 2022, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction Cost of Timber Buildings. Chalmers University of Technology. 2022. Available online: https://research.chalmers.se/publication/532727/file/532727_Fulltext.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Perković, N.; Skejić, D.; Rajčić, V. Numerical Analysis of Fire Resistance in Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Constructions Using CFD: Implications for Structural Integrity and Fire Protection. Forests 2024, 15, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSA O86–14; Engineering Design in Wood. CSA Group: Singapore, 2014.

- American Wood Council. Fire Design Specification for Wood Construction; American Wood Council: Leesburg, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AWC. Technical Report 10-Calculating the Fire Resistance of Exposed Wood MemberM; AWC: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AS/NZS 1720.4:2019; Timber Structures—Part 4: Fire Resistance of Timber Elements. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia.

- XLAM. Australia & New Zealand Fire Design Guide. Available online: https://xlam.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/004-XLam-Fire-Design-Guide-V2-August-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Buchanan, A.H.; Dunn, A.; O’Neill, J.; Pau, D. Fire Safety of CLT Buildings in New Zealand and Australia. Wood Fiber Sci. 2018, 50, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, B.; Mikkola, E.; Stein, R.; Frangi, A.; König, J.; Dhima, D.; Hakkarainen, T.; Bregulla, J. Fire Safety in Timber Buildings: Technical Guideline for Europ; SP Report 2010:19; SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E119; Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Buchanan, A.; Östman, B. Fire Safe Use of Wood in Buildings: Global Design Guide, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippel, M.; Schmid, J.; Frangi, A. Fire design of CLT—Comparison of design concepts, in Cross Laminated Timber—A Competitive Wood Product for Visionary and Fire Safe Buildings; Falk, A., Dietsch, P., Schmid, J., Eds.; KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Division of Building Materials: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; pp. 101–122. ISBN 978-91-7729-043-8. [Google Scholar]

- Frangi, A.; Fontana, M.; Hugi, E.; Jübstl, R. Experimental analysis of cross-laminated timber panels in fire. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mei, F.; Liao, J.; Li, W. Experimental and numerical analysis on fire behaviour of loaded cross-laminated timber panels. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2020, 23, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, H. Experimental and numerical analysis of residual load-carrying capacity of cross-laminated timber walls after fire. Structures 2021, 30, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Ruane, K.; O’Ceallaigh, C.; Jaksic, V. Review of comparative analysis of experimental testing and finite element (FE) analysis of cross-laminated timber (CLT) under fire. In Proceedings of the Civil Engineering Research in Ireland, Galway, Ireland, 29–30 August 2024; pp. 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, F.; Hadden, R.; Bisby, L. Influence of Adhesive on Decay Phase Temperature Profiles in CLT in Fire. In Proceedings of the 12th Asia-Oceania Symposium on Fire Science and Technology (AOSFST 2021), Online, 7–9 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinka, S.L.; Sullivan, K.; Pei, S.; Ottum, N.; Bechle, N.J.; Rammer, D.R.; Hasburgh, L.E. Small scale tests on the performance of adhesives used in cross laminated timber (CLT) at elevated temperatures. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 95, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszyński, L.; Gupta, R.; Hong, S.H.; Osborn, N.; Pickett, B. Fire resistance of unprotected cross-laminated timber (CLT) floor assemblies produced in the USA. Fire Saf. J. 2019, 107, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaitis, D.I.; Asimakopoulou, E.K.; Founti, M.A. Fire protection of light and massive timber elements using gypsum plasterboards and wood based panels: A large-scale compartment fire test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Hadjisophocleous, G.; McGregor, C. Experimental Study of Combustible and Non-combustible Construction in a Natural Fire. Fire Technol. 2015, 51, 1447–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Morrisset, D.; Colic, A.; Bisby, L. Comparative performance of protective coatings for mass timber structures. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2023), Oslo, Norway, 19–22 June 2023; pp. 1788–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippel, M.; Leyder, C.; Frangi, A.; Fontana, M. Fire Tests on Loaded Cross-laminated Timber Wall and Floor Elements. Fire Saf. Sci. 2014, 11, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, T.R.; Spearpoint, M.J. Delay of Onset of Charring to CLT Using Different Encapsulation Board Materials. SESOC J. 2016, 29, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Friquin, K.L.; Grimsbu, M.; Hovde, P.J. Charring rates for cross-laminated timber panels exposed to standard and parametric Fires. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering, Trentino, Italy, 20–24 June 2010; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- van der Westhuyzen, S.; Walls, R.; de Koker, N. Fire tests of South African cross-laminated timber wall panels: Fire ratings, charring rates, and delamination. J. South Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2020, 62, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangi, A.; Fontana, M.; Knobloch, M.; Bochicchio, G. Fire behaviour of cross-laminated solid timber panels. Fire Saf. Sci. 2008, 9, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; O’Ceallaigh, C.; Ruane, K.; Macilwraith, A. Experimental and Finite Element Analysis of Irish Sitka Spruce CLT Floor Panels Under Exposure to Standard Fire Conditions. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE), Oslo, Norway, 16 June 2023; pp. 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucherini, A.; Razzaque, Q.S.; Maluk, C. Exploring the fire behaviour of thin intumescent coatings used on timber. Fire Saf. J. 2019, 109, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, F.; Randmael, F.; Wan, W.; Bisby, L.; Hadden, R.M. Structural response of cross-laminated timber compression elements exposed to fire. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 91, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasburgh, L.; Bourne, K.; Peralta, P.; Mitchell, P.; Schiff, S.; Pang, W. Effect of Adhesives and Ply Configuration on the Fire Performance of Southern Pine Cross-Laminated Timber. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering, Vienna, Austria, 22–25 August 2016; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, J.; Mizukami, T.; Naruse, T.; Araki, Y. Fire Resistance of Timber Panel Structures Under Standard Fire Exposure. Fire Technol. 2016, 52, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizhong, Y.; Yupeng, Z.; Yafei, W.; Zaifu, G. Predicting charring rate of woods exposed to time-increasing and constant heat fluxes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2008, 81, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangi, A.; Fontana, M. Charring rates and temperature profiles of wood sections. Fire Mater. 2003, 27, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, D.; Hagman, O. Mechanics of diagonally layered cross-laminated timber. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2018), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 20–23 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, F.; Klippel, M.; Dagenais, C.; Dunn, A.; Janssens, M.L.; Kagiya, K. Requirements for engineered wood products and their influence on the structural fire performance. In Proceedings of the WCTE2018, World Conference on Timber Engineering, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 20–23 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Abu, A.K. Structural Design for Fire Safety; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Aloisio, A.; Pasca, D.P.; Fragiacomo, M. Fire resistance of wooden dowelled cross-laminated timber panels under in-plane loading. Eng. Struct. 2025, 340, 120592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, H.; Kotsovinos, P.; Richter, F.; Thomson, D.; Barber, D.; Rein, G. Review of fire experiments in mass timber compartments: Current understanding, limitations, and research gaps. Fire Mater. 2023, 47, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fischer, E.C. Review of large-scale CLT compartment fire tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318, 126099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, D.; Dagenais, C. Fire Safety Challenges of Tall Wood Buildings—Phase 2: Task 5—Experimental Study of Delamination of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) in Fire; American Wood Council: Leesburg, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Leroux, P.; Lafrance, P.-S.; Gratton, K.; Gibbs, E.; Weinfurter, M. Fire Testing of Rooms with Exposed Wood Surfaces in Encapsulated Mass Timber Construction; RISE Research Institutes of Sweden: Boras, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McNamee, R.; Zehfuss, J.; Bartlett, A.I.; Heidari, M.; Robert, F.; Bisby, L. Enclosure fire dynamics with a cross-laminated timber ceiling. Fire Mater. 2020, 45, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberley, R.; Putynska, C.G.; Bolanos, A.; Lucherini, A.; Solarte, A.; Soriguer, D.; Gonzalez, M.G.; Humphreys, K.; Hidalgo, J.P.; Maluk, C.; et al. Description of small and large-scale cross laminated timber fire tests. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 91, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1396/C1396M-22; Standard Specification for Gypsum Board. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Hopkin, D.; Węgrzyński, W.; Gorska, C.; Spearpoint, M.; Bielawski, J.; Krenn, H.; Sleik, T.; Blondeau, R.; Stapf, G. Full-Scale Fire Experiments on Cross-Laminated Timber Residential Enclosures Featuring Different Lining Protection Configurations. Fire Technol. 2024, 60, 3771–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberley, R.; Inghelbrecht, A.; Yu, Z.; Torero, J.L. Self-extinction of timber. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2017, 36, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, A.S.; Hox, K.; Mikalsen, R.F.; Friquin, K.L. Large-scale fire experiments in a cross-laminated timber compartment with an adjacent corridor—Partly and fully protected with a water sprinkler system. Fire Saf. J. 2024, 148, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1991-1-2; Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures. Part 1-2: General Actions—Actions on Structures Exposed to Fire. European Committee for Standardisation (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- Su, J.; PS, L.; Hoehler, M.; Bundy, M. Fire Safety Challenges of Tall Wood Buildings—Phase 2: Task 2 & 3—Cross Laminated Timber Compartment Fire Tests (FPRF-2018-01); Fire Protection Research Foundation: Quincy, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsovinos, P.; Christensen, E.G.; Rackauskaite, E.; Glew, A.; O'LOughlin, E.; Mitchell, H.; Amin, R.; Robert, F.; Heidari, M.; Barber, D.; et al. Impact of ventilation on the fire dynamics of an open-plan compartment with exposed timber ceiling and columns: CodeRed #02. Fire Mater. 2023, 47, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsovinos, P.; Rackauskaite, E.; Christensen, E.; Glew, A.; O'LOughlin, E.; Mitchell, H.; Amin, R.; Robert, F.; Heidari, M.; Barber, D.; et al. Fire dynamics inside a large and open-plan compartment with exposed timber ceiling and columns: CodeRed #01. Fire Mater. 2023, 47, 542–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čolić, A.; Wiesner, F.; Spearpoint, M.; Hopkin, D.J.; Bisby, L.A. Timber Structural Loads on Trial: Design vs. Experiments in Fire Conditions. pp. 1206–1216. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393373413_timber_structural_loads_on_trial_design_vs_experiments_in_fire_conditions (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Scaling study on the fire resistance of cross-laminated timber floors. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 85, 108679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.; Klippel, M.; Just, A.; Frangi, A.; Tiso, M. Simulation of the Fire Resistance of Cross-laminated Timber (CLT). Fire Technol. 2018, 54, 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.V.Y.; Tee, K.F.; Yau, T.M. Numerical Study of Cross-Laminated Timber Under Fire. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Seminar on Fire and Explosion Hazards (ISFEH9), Petersburg, Russia, 21–26 April 2019; pp. 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, J.M.; Kodur, V.K.R.; Mason, J. User’s Manual for SAFIR 2004—A Computer Program for Analysis of Structures Subjected to Fire; University of Liege, Department Structures du Ge’nie Civil—Service Ponts et Charpentes: Liege, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abougharib, A.; Naser, M.Z.; Paradis, G.; Wiesner, F. Solid temperature prediction for CLT walls in fire using supervised machine learning. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering 2025, Brisbane, Australia, 22–26 June 2025; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, N.; O’Neill, J.W.; Spellman, P.M.; Abu, A.K.; Moss, P.J.; Buchanan, A.H.; Winter, S. Parametric study of modelling structural timber in fire with different software packages. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Structures in Fire, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–8 June 2012; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martinez, J.E.; Alonso-Martinez, M.; del Coz Diaz, J.J.; Álvarez Rabanal, F.P. Non-linear simulation of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) delamination under fire conditions using FEM numerical model. Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Recent Advances in Nonlinear Design, Resilience and Rehabilitation of Structures, Coimbra, Portugal, 16–18 October 2019; pp. 391–398. Available online: https://eccomas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Proceedings-Corass-2019.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Xing, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H. Research on fire resistance and material model development of CLT components based on OpenSees. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayajneh, S.M.; Naser, J. Fire Spread in Multi-Storey Timber Building, a CFD Study. Fluids 2023, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, D.; Jang, S.; Jadidi, M.; Giustini, G.; Keshmiri, A.; Mahmoudi, Y. Physics-informed neural networks for heat transfer prediction in two-phase flows. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 221, 125089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmohammadian, R.; Put, F.; Van Coile, R. Physics-Informed Surrogate Modelling in Fire Safety Engineering: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| k0 | |

|---|---|

| t < 20 min | t/20 |

| t ≥ 20 min | 1.0 |

| Density (kg/m3) | Material | β0 (mm/min) | βn (mm/min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥290 | Softwood and Beech | Glued–laminated timber | 0.65 | 0.70 |

| Solid timber | 0.65 | 0.80 | ||

| 290 | Hardwood | Solid or glued–laminated timber | 0.65 | 0.70 |

| ≥450 | 0.50 | 0.55 | ||

| LVL with a density of ≥480 kg/m3 | 0.65 | 0.70 | ||

| Protective Claddings | Condition | Equation b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A, F, H | Single layer | Location adjacent to ≤2 mm unfilled gaps | tch = 2.8 hp − 14 | (6) |

| Location adjacent to >2 mm unfilled gaps | tch = 2.8 hp − 23 | (7) | ||

| Type A or H | Two layers a | Use Equation (6), with hp calculated as hp = 1 × outer layer thickness + 0.5 × inner layer thickness | ||

| Type F | Use Equation (6), with hp calculated as hp = 1 × outer layer thickness + 0.8 × inner layer thickness | |||

| Standard/Code | Region | Design Basis | Charring Rate/Fire Resistance Assumptions | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurocode 5 (EN 1995-1-2) [16] | Europe | Reduced cross-section and effective charring | ~0.65 mm/min (softwoods); zero-strength layer (ZSL) of 7 mm | Most widely used baseline; no specific design method for CLT; handbook used as advisory guidance for CLT fire design [53]. |

| CSA O86 [47] | Canada | Mechanics-based; tabulated fire ratings | 0.65 mm/min (1st lamella); 0.8 mm/min deeper layers; 7 mm ZSL [15] | Based on Canadian test data; includes buckling reduction factor and encapsulation allowances. |

| NDS [48] | USA | Mechanics-based (NDS) + prescriptive ratings (IBC, ASTM E119) [54] | 0.635 mm/min + 20% (includes heated-zone strength/stiffness loss) [48] | Empirical equation for lamella fall-off; instability via kc; only covers exposed members [15]. |

| AS 1720.4 [50] | Australia/NZ | Reduced cross-section method | 0.65 mm/min for radiata pine; 7 mm ZSL assumed | CLT not explicitly covered; performance-based compliance common; Eurocode and manufacturer guides often used. |

| Authors and References | Research Focus in Terms of Fire Performance of CLT | Authors and References | Research Focus in Terms of Fire Performance of CLT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wiesner et al. [61] Zelinka et al. [62] Muszyński et al. [63] | Adhesive performance | Kolaitis et al. [64] Li et al. [65] Johnson et al. [66] | Protective cladding |

| Bartlett et al. [14] | Heating conditions, sample orientation, and size | Klippel et al. [67] | CLT layup, wall and floor panels, support conditions |

| Frangi et al. [57] | Adhesive, thickness of layer | Wang et al. [58] | Thickness and number of layers |

| Moser et al. [68] Yasir et al. [42] | Protective cladding | Friquin et al. [69] | Layer and panel thickness, fire intensity |

| Westhuyzen et al. [70] | Analysis of the fire performance of CLT wall panels | Mindeguia et al. [27] | Thermo-mechanical behaviour of CLT slab under fire |

| Xing et al. [35] | Number of layers, load ratios, validation of FE analysis, thickness of the zero-strength layer (ZSL) | Frangi et al. [71] | Validation of FE analysis and comparison of CLT panels with homogeneous timber elements. |

| Yasir et al. [72] | Protective cladding, number of layers, validation of FE analysis | Lucherini et al. [73] | Intumescent coating |

| Wiesner et al. [74] | Layers layups | ||

| Hasburgh et al. [75] | Ply configuration, types of adhesives | Suzuki et al. [76] | Adhesive, layer thickness, wood specie |

| Reference | Layer Layup (mm) | Adhesive c | Charring Rate (mm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friquin et al. [69] | 32-41-34-41-32 | MUF | 0.48 |

| 31.5-21-32-21-32-21-32-21-28.5 | 0.71 | ||

| Xing et al. [35] | 33-33-33 | PUR | 0.67 |

| 0.92 a | |||

| 21-21-21-21-21 | 0.77 | ||

| 1.18 a | |||

| Wiesner et al. [74] b | 33-34-33 | MF | 0.82–0.88 |

| 20-20-20-20-20 | 0.98–1.0 |

| Reference | Layer Layup (mm) | Adhesive | Panel Size (m2) | Charring Rate (mm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muszyński et al. [63] | 35-35-35-35-35 | PUR | 5.48 × 4.26 | 0.63 |

| MF | 0.55 | |||

| Frangi et al. [57] | 10-10-10-10-20 | MUF | 1.15 × 0.95 | 0.58 |

| PU1 | 0.94 | |||

| PU2 | 0.90 | |||

| PU3 | 1.00 | |||

| PU4 | 1.08 |

| Experiment ID | Lining Configuration | Initial Exposed CLT Area | Experiment ID | Lining Configuration | Initial Exposed CLT Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a and 1b | Triple-layer lined wall and ceiling | 0% (fully encapsulated) | 6a | 2 × walls triple-lined, ceiling and 1 × wall exposed | 46% |

| 2a | Triple-lined walls, Single-lined ceiling | 0% | 7a | Ceiling and 1 × wall triple-lined, 2 × walls exposed | 38% |

| 3a and 3b | Triple-lined walls, ceiling exposed | 26% | 8a | 1 × wall triple-lined, Single-lined ceiling, 2 × walls exposed | 38% |

| 4a | 2 × walls triple-lined, 1 × wall single-lined, ceiling exposed | 26% | 9a | Triple-layer on 2 × walls and ceiling, 1 × wall exposed | 19% |

| 5a | 2 × walls triple-lined, 1 × wall double-lined, ceiling exposed | 26% |

| Compartment Surface | Test Number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 1-4 | 1-5 | 1-6 | 1-2 | 1-3 | |

| Size of Opening (1.8 m × 2.0 m) | Size of Opening (3.6 m × 2.0 m) | |||||

| Number of Protective Layers of Gypsum Plasterboard (Type X) | ||||||

| W1 (9.1 m × 2.7 m) | 3 | 3 | Exposed | Exposed | 2 | Exposed |

| W2 (4.6 m × 2.7 m) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| W3 (9.1 m × 2.7 m) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| W4 (4.6 m × 2.7 m) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Ceiling (9.1 m × 4.6 m) | 3 | Exposed | 3 | Exposed | 2 | 2 |

| Model Type | Authors | Element Type * | Mesh Size (mm3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermo-mechanical model | Bai et al. [59] | C3D8R | 10 × 10 × 7 |

| Wang et al. [58] | |||

| Heat transfer model | Xing et al. [35] | DC3D8 | 10 × 10 × 1 |

| Wang et al. [58] | 5 × 5 × 3.5 |

| Approach | Primary Predictions | Strengths | Limitations/Challenges | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE | Temperature profiles, charring depth, deformation, failure time | Accurately couples thermal and mechanical responses; reliable for member and assembly scale fire design | Computationally expensive, sensitive to input (adhesive degradation, moisture), less suited for fully coupled compartment simulations | [58,59] |

| CFD | Fire-induced flow, heat flux distribution, flame spread, smoke layer development in compartments | Captures compartment dynamics and fire growth; supports ventilation and cladding studies | Does not resolve structural response, high model uncertainty, validation data scarce, high computational cost | [46,106] |

| ML | Time–temperature prediction, charring rate | Very fast once trained; good for sensitivity and real-time forecasting | Needs high-quality training data, lacks physical interpretability, extrapolation outside training range uncertain | [102] |

| PISM | Temperature distribution, heat transfer, convection, fire dynamics, structural fire engineering, material behaviour | Heat transfer, physically interpretable, emerging research direction | Convergence difficulties, uncertainty quantification, data efficiency, multi-physics integration | [107,108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yasir, M.; Ruane, K.; O’Ceallaigh, C.; Jaksic, V. Fire Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber: A Review of Standards, Experimental Testing, and Numerical Modelling Approaches. Fire 2025, 8, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100406

Yasir M, Ruane K, O’Ceallaigh C, Jaksic V. Fire Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber: A Review of Standards, Experimental Testing, and Numerical Modelling Approaches. Fire. 2025; 8(10):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100406

Chicago/Turabian StyleYasir, Muhammad, Kieran Ruane, Conan O’Ceallaigh, and Vesna Jaksic. 2025. "Fire Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber: A Review of Standards, Experimental Testing, and Numerical Modelling Approaches" Fire 8, no. 10: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100406

APA StyleYasir, M., Ruane, K., O’Ceallaigh, C., & Jaksic, V. (2025). Fire Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber: A Review of Standards, Experimental Testing, and Numerical Modelling Approaches. Fire, 8(10), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100406